Conference

Community Leaders

Brand Interpreter

Launch, Deploy, Release: ASL Interpreting in the Tech Sector

To Be or Not To Be Dependent on Interpreters?

Coalition for Sign Language Equity in Technology (Co-SET)

Conference

Community Leaders

Brand Interpreter

Launch, Deploy, Release: ASL Interpreting in the Tech Sector

To Be or Not To Be Dependent on Interpreters?

Coalition for Sign Language Equity in Technology (Co-SET)

President | Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI

Vice President | Shonna Magee, MRC, CI & CT, NIC Master, OTC

Secretary | Vacant

Treasurer | Kate O’Regan, MA, NIC

Member-at-Large | Mona Mehrpour, NIC

Deaf Member-at-Large | Glenna Cooper

Region I Representative | Christina Stevens, NIC

Region II Representative | M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region III Representative | Vacant

Region IV Representative | Jessica Eubank, NIC

Region V Representative | Rachel Kleist, CDI

Interim CEO | Ritchie Bryant, CDI, CLIP-R

Director of Finance and Accounting | Jennifer Apple

Finance and Accounting Manager | Kristyne Reeds

Staff Accountant | Bradley Johnson

Human Resources Manager | Cassie Robles Sol

Director of Member Services | Ryan Butts

Member Services Manager | Kayla Marshall, M.Ed., NIC

Member Services Specialist | Vicky Whitty

CMP Manager | Ashley Holladay

CMP Specialist | Emily Stairs Abenchuchan, NIC

Certification Manager | Catie Colamonico

Certification Specialist | Jess Kaady

Communications Director | S. Jordan Wright, PhD

Communications Manager | Jenelle Bloom

Publications Coordinator | Brooke Roberts

EPS Manager | Tressela Bateson, MA

EPS Specialist | Martha Wolcott

Director of Government Affairs | Neal Tucker

Conference Planner | Julie Greenfield

CASLI Director of Testing | Sean Furman

CASLI Testing Manager | Amie Smith Santiago, MS, NIC

CASLI Testing Specalist | Melissa Kononenko

Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI RID President

Technology is rapidly reshaping the interpreting field, bringing both exciting innovations and complex challenges. From remote interpreting platforms to AI-powered transcription and translation tools, technology is no longer just a support—it’s becoming central to how we work.

In my own practice, I use tech to enhance accessibility and efficiency, always with the understanding that it complements, not replaces, the live ASL interpreter. I’m closely following the development of AI language models and speech recognition systems. While these tools continue to improve, they still struggle to grasp cultural nuance, tone, and context—the very spaces where live ASL interpreters thrive.

Looking ahead, I see AI as a valuable partner in our work, especially for tasks like preparation, terminology management, and real-time support. But the interpreter ’s role won’t disappear—it will evolve. This is a critical moment for our profession to shift mindsets: rather than fear being replaced, we can position ourselves as leaders in shaping how technology is used. The more we engage with these tools, the more influence we have in ensuring they serve—not sideline—our communities.

As this transformation unfolds, we must advocate for ethical tech use and prioritize quality, access, and equity in every advancement. And while tech is the focus of this issue, it’s also important to spotlight the broader issues that shape our profession—interpreter wellness, fair compensation, and ongoing professional growth. As our tools evolve, so too must the systems that support interpreters and the communities we serve.

ASL Unavailable

Greetings, members!

Master, OTC

The past several months have been full of purposeful energy behind the scenes, and I am pleased to share a snapshot of my work as your Vice President of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID). Much of what I do is not always visible, but it is critical to the organization’s day-to-day operations and long-term stability. I have been deeply involved in supporting internal processes, coordinating with consultants, and helping steer strategic initiatives—all of which contribute to keeping RID on track and moving forward. While some of these responsibilities are not always public-facing, they are essential to ensuring that RID operates effectively and responsibly.

In addition to my core duties, I have also stepped in to support fellow Board members when needed, helping to ensure continuity across projects and reinforcing our collective commitment to service and accountability. Collaboration and flexibility have been key as we navigate a full agenda and position ourselves for continued growth.

As a newer member of the Board, still within my first year of service, I will be the first to admit that the learning curve has been real—but it has also been incredibly rewarding. I am fortunate to be surrounded by some of the most thoughtful, dedicated, and principled individuals I have worked with in a long time. These are people who lead with heart and consistently center their decisions on what is best for the membership and the integrity of our profession. Their guidance, collaboration, and commitment have not only supported my own growth but have also reinforced my belief in the strength and future of RID. I am truly grateful to be part of this team.

One of the exciting projects I have been directly involved in is the planning for the 2025 RID National Conference. From engaging in Board-level discussions to initiating outreach to potential sponsors and partners, I am striving to support what promises to be an inspiring and forward-looking event. I sincerely hope to see many of you there—July 31 through August 3!

I have also been reaching out to members regarding open Board positions and encouraging leadership engagement across our regions. Strengthening the leadership pipeline is vital to RID’s future, and I am grateful to those who have expressed interest or are considering service.

Serving as your Vice President is both an honor and a responsibility I do not take lightly. I remain committed to the work—visible and invisible—that strengthens RID’s foundation and supports our shared mission.

M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region II Representative

Region II has been busy this spring and preparing for the summer as we have several offerings for professional learning opportunities throughout the region in each of our Affiliate Chapters.

Alabama RID (ALRID) has a lot happening with two workshops and their general business meeting occurring within the next few months. June 5, 2025 we will have our general business meeting along with two workshops. “Interpreting Parliamentary Procedures, Basics for Effective Interpreting” and “Intro to Emergency Management.”

Georgia RID (GaRID) will be having a member appreciation day soon; they will be providing food, workshop, prizes, and having members assess their skills to see what they can bring to GaRID!

Florida RID (FRID) will be working on partnership as part of a mentoring experience with some local universities. This will be like a speed dating type of event but with networking and mentoring as they will pair recent graduates with seasoned interpreters.

Mississippi RID (MSRID) is continuing to rebuild their membership and board activities.

South Carolina RID (SCRID) is working on developing their education regulations. Want to start with at least a 3.5 EIPA score and effective for the 2026-2027 school year. They are also working on a 2-part book study based off of the book “Black Like Me” for this summer.

Tennessee RID (TRID) is having an Educational Interpreter Institute hosted by the Tennessee school for the deaf on July 15 th and this event will be a virtual only option.

Virginia RID is developing a mentoring program based off of a 3-year grant opportunity. The grant will allow them to train interpreter mentors, language models, and assessors. They are engaging in monthly board meetings. On June 7 from 9 to 1pm, there will be the membership Meeting, which will be virtual.

Rachel Kleist, CDI Region V Representative

Hello! Region V has been very busy preparing for the summer! We have many virtual workshops coming up - keep an eye out for that in the monthly e-news, we will be sharing more about those there.

Exciting news!! Region V has three scholarships in the amount of $500 each to support Region V members going to the 2025 RID National Conference this summer, July 31 - Aug 3, in Minneapolis, Minnesota!

To apply, you will need to fill out a general list of demographic information and create a video between 3 - 5 minutes long. You can find out more at the Google Form application here.

The application is available now and closes June 27th. Award recipients will be notified on July 5th, in time to register for the conference. Share with your network and encourage all to apply today! Looking forward to seeing you at the conference!

Juliana Apfel (she/her/ella) is a Certified Deaf Interpreter, translator, consultant, and presenter originally from Arizona and now based in Washington, D.C. She holds two Master of Science degrees—one in Forensic Psychology from Arizona State University and another in Healthcare Interpreting from Rochester Institute of Technology—along with a Bachelor of Science from Gallaudet University. Juliana’s interpreting experience spans forensic, legal, medical, post-secondary, K–12, and platform settings. She is also a mentor, interpreter educator, and trainer who supports interpreters and institutions in justice-based, trauma-informed practice. Juliana currently serves as Chair of the Legal Interpreters Member Section for the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Her work is deeply informed by her intersectional experience as a Deaf, queer, Latine woman and her commitment to language access, equity, and accountability across the interpreting profession.

Ku Mei is a Deaf-parented, BIPOC leader whose life’s work has centered on bridging communication gaps between communities. With over 25 years of experience as an interpreter, educator, mentor, and executive, she brings a unique lens to language access, intersectionality, and cultural connection. Currently the COO of LingoForce and a board member of CASLI, Ku Mei is dedicated to creating systems that empower Deaf consumers, interpreters, and businesses alike.

Angela Blackdeer is the founder and CEO of Verto, a company transforming interpreting services through innovation, inclusion, and culturally grounded strategy. A nationally certified sign language interpreter and 2012 Interpreter of the Year, Angela brings over 20 years of experience to her work. She is the creator of LingoForce, a powerful platform for interpreter scheduling and credential management that supports interpreters in new and accessible ways. Her work goes beyond technology—Angela is deeply committed to advancing health equity and access in underserved communities.

Angela holds a degree in Special Education and Rehabilitation from the University of Arizona (Summa Cum Laude) and a Master’s in Organizational Leadership from St. Catherine University. Her leadership is rooted in her Dakotah values, centering relationships, collective responsibility, and systems that uplift interpreters, Deaf communities, and care providers alike. Wicohan, mitakuye oyasin. A sought-after speaker and strategist, Angela is known for her clarity, creativity, and dedication to challenging the status quo. She believes that when interpreters are supported, entire communities thrive.

At the upcoming RID National Conference 2025, themed Now What? En Avant! Onward!, we are honored to serve as community leaders guiding the En Avant morning sessions.

We do not represent RID leadership, nor are we RID staff.

We are three community members — interpreters, advocates, and changemakers — answering a call we feel deep in our bones: to help move our profession forward with intention, honesty, and shared responsibility.

→ Forward with truth.

→ Forward with accountability.

→ Forward with a collective commitment to do better.

These morning sessions are not meant to be another place to simply talk. They are an invitation — to pause, to process, to begin again.

Across four mornings of intentional space, reflection, and connection, En Avant Sessions offer a journey: a space to examine where we’ve been, where we are now, and what we must build for the future.

We are living through a moment of immense change. The field of interpreting is being reshaped in real time — by shifting societal values, technological disruption, widening equity gaps, and ongoing tension between credentialing and community trust. Many of us are asking: What is RID now? What could it become? And: are we, collectively, ready for what that transformation requires?

In these sessions, we are not offering easy answers. We are offering space. Space to return to ourselves, our stories, and each other. Space to listen. To share. To be challenged. Space to speak truths that have too often gone unheard — and space to hear truths that may unsettle us.

We will unpack the feelings — individually, and together. Grief. Frustration. Burnout. Hope. Possibility. All are welcome in the room.

This journey will not be a performance. It will not be polished or perfect. But it will be real. We aim to center trust, bring honesty into the room — both joyful and uncomfortable — and help move our community beyond surface talk and into grounded action.

We come with different lived experiences, but a shared belief that this profession must evolve. Not just structurally, but spiritually.

Together, we bring a unique lens shaped by our intersectionality and our identities — lived experiences that continue to inform how we show up, listen, and lead.

We have seen firsthand what happens when community voices are silenced, when systems prioritize neutrality over justice, and when conversations about access are divorced from the people most affected by it.

This is why we said yes. We are not guiding these sessions because we have all the answers. We are guiding them because we are willing to walk the road with you.

It starts with personal reflection. It deepens with collective courage. It moves through shared action.

This journey starts with each of us — with the courage to listen, to reflect, to be uncomfortable, and to grow.

It is about honoring what has already been done, seeing what is still in front of us, and choosing to walk forward — together.

It starts with you. It starts with us.

Let’s do this — together.

We invite every attendee to join us with open minds, open hearts, and a readiness to co-create the future of our field and our community. And to join others in doing the same.

The time for change is now. Let’s move En Avant — forward.

Josh Pennise has been an RID-certified interpreter for over 25 years, specializing in corporate, conference, and higher education settings. He taught for a decade in his local ITP and is a frequent workshop presenter at RID and other professional events nationwide. For more than 20 years, Josh has contributed volunteer service to RID at various levels, including six years on the Board of Directors. He held leadership roles for 16 years at Sorenson Communications, where he founded and directed Sorenson Interpreting, and later served as CEO of TCS Interpreting in Silver Spring, MD. Currently, he provides strategic advising to businesses and individuals through The Smithson Company and serves as vice president of the Association of Language Companies. Josh focuses his work on areas where he can make meaningful contributions to improving interpreting services for the communities we serve.

You do not have a brand, right? It sounds so commercial, so business, so antithetical to community-based practice. But the thing is, you have a brand whether you want one or not.

Jeff Bezos said it best: “Your brand is what other people say about you when you’re not in the room.”

That quote blurs the line between brand and reputation, and that is worth unpacking. Your brand is the image you intentionally put out into the world including your values, your voice, your style, and your promises. Your reputation is the result of how well you deliver on that promise.

One is crafted. The other is earned.

Your name conjures something specific in the minds of hiring managers, Deaf consumers, and co-interpreters. Your brand shapes whether people look forward to working with you or not. It influences whether or not companies choose to book you.

But here is the part that matters: your brand is not just spin. It is not about slick marketing or pretending to be something you are not. A strong brand is authentic, created by deliberate actions to make sure your values shine clearly, without noise that confuses the picture. We are talking about the opposite of manipulation: clarity. Your brand makes sure who you really are comes through—before, during, and after every interaction.

Given that we all have a brand, the question is not if, but what. What are you projecting? What do others see? And most importantly: is it aligned with the interpreter you actually want to be?

Now is the time to get intentional: understand your brand, design it authentically, and close the gap between how you are seen and how you want to be remembered.

It is important to first understand how people view you. Are you trustworthy? Are you dependable? Are you others-focused? A great first step is to take inventory of both how you rate yourself on key qualities and how you think your behaviors portray you. For example, you may feel that you are a very trustworthy person, however do your actions on the job support this? Do you talk negatively about other interpreters to your teammate for the day? Do you share job information when you probably should not because the story is just too good? These actions may be incongruent with your values and how you want the world to see you.

To better understand how people see your brand you need an external view of yourself. A good first step is to ask trusted colleagues to tell you how they think people see you. Are you known for any positive or negative attributes? What do people think when they see you are their teammate? Does anything about you cause anxiety? This is a tough favor to ask people to do- giving honest feedback can be painful for both parties and it can feel risky to the relationship. As Gloria Steinem put it, “the truth will set you free. But first, it will piss you off.”

Make sure you set the table for effective feedback to be provided. Give people time to digest your request and give you a thoughtful answer instead of asking them for a spur of the moment analysis while co-interpreting together. Send them an email setting the stage by describing the purpose of your ask as well as your commitment to both accept the feedback and maintain a positive relationship with the person. Give them the option to discuss their thoughts with you in person, virtually, or over email, recognizing that people have different levels of comfort with candid talk.

The best way to get a real sense of how you are seen by those around you is by taking a 360-degree assessment. This type of evaluation is conducted by an independent third-party and surveys stakeholders around you about your behaviors and how you make others feel. For a working interpreter, this could include colleagues, Deaf consumers, hearing consumers, as well as managers and schedulers from the interpreting agencies that know you. Additionally, you answer the same questions, providing one of the most valuable findings in the results: the gap between how you see yourself and how others experience you. You can create an anonymous 360-degree assessment on your own using free tools like Google Forms or pay for a pre-packaged service tailored to interpreters like the one provided by The Smithson Company.

Your brand should authentically represent you. It is not to get jobs you would not otherwise qualify for, but to showcase who you are and what you can do. To do this consider the following areas of introspection and exploration.

Core Values. Your brand should reflect what you personally value. For example, one of my top values is “having positive impact.” That value has led me over the years to be active in our professional organization and do things I think will impact our field (for example, writing this article for the VIEWS). I hope that over time it becomes something people recognize in my brand without me telling them first. Articulating your core values can be a challenge- they often operate deep within you sometimes subconsciously. Consider taking one of many online tests to flesh out a bit more clearly what is truly important to you.

Value Proposition. Think about what differentiates you from other interpreters with whom you work. Is it your educational background? Your years of experience? Perhaps you handle high-stress environments with ease, are comfortable working in warehouses overnight supporting Deaf employees, or love working with Deaf kids. These are aspects of your professional practice that set you apart from another interpreter reading this article right now.

Specialization. Are you a generalist or do you have a specialty? Have you developed a depth of practice or understanding in an area like medical interpreting or elementary education? If so, think about how to showcase this.

Professionalism. Professionalism here is not meant as conformity. It means consistency, respect, and showing up in a way that aligns with your clients’ expectations and your own values. Do your behaviors engender trust in those around you? Do you contribute in ways that show you are others-focused?

“Customer” Service. Do you show that you are not the center of the interpreted event by focusing on the needs of your consumers, in supporting your team (instead of checking your phone), and in making sure the company who hired you is proud to have you representing them?

Note: Generated by author.

For me, these five elements are essential for creating an interpreter ’s brand. Think about where you are on each of these measures. Use tools such as a 360 or other peer-based feedback mechanism. If you are where you want to be, congratulations; and, think a bit harder. Those gaps are ground for improvement. Use these research-based techniques to effect change:

1. Make a plan and write it down.

2. Tell someone else about what you intend to do.

3. Set reminders for yourself to check in monthly and take a self-inventory of your progress.

Your brand is communicated chiefly by your actions. It is important to practice our profession in a way that aligns with how we want to appear in the world. Regardless of what we say, what we do communicates the most to people.

However, we communicate an awful lot asynchronously in today’s world. A practicing interpreter does well to have a polished, professional resume that represents not only their credentials and work history, but also their brand.

A 2025 survey of hiring managers engaging ASL interpreters showed that fully 88% rated resumes as somewhat or very important in their hiring decisions. 79% said that a professional resume makes them more likely to hire an interpreter candidate. Only 48%, though, said that the average resume they see provides sufficient information. This is clearly an opportunity for improvement in our field.

A clear, concise resume should answer some basic questions that hiring managers are trying to answer, such as:

• Do they have skill and ability to legally work?

• Is the person trustworthy?

• Where could I use the person?

• Is the person professional?

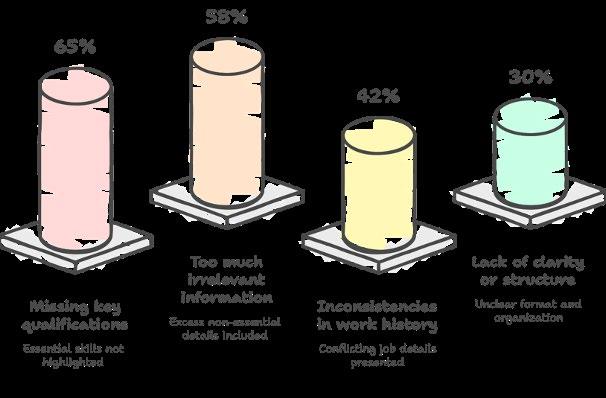

In the same survey, hiring managers expressed frustration around some key inadequacies in interpreter resumes such as missing information about credentials or work history, irrelevant information such as early non-interpreting jobs, inconsistencies in work history, and general lack of clear and concise information.

Note: Survey of 52 hiring managers and recruiters who hire ASL interpreters conducted by author in 2025.

Interpreter’s brand is reinforced today as well by social media. Interpreter as influencer is a pretty modern phenomenon that this author is not qualified to comment on in any depth. However, recruiters, co-interpreters, and Deaf consumers do use Facebook and LinkedIn to try and understand who an interpreter is before they take their place on the hot seat. This begs the question of what these social media platforms contribute to the interpreter’s image?

LinkedIn can be a particularly helpful tool for interpreters in both setting a professional tone and establishing a brand. In particular the “headline” and “about” sections offer a great place to summarize your brand and values. As an example, take a look at this fictional interpreter’s “about” section:

A well-crafted page is often the first impression a recruiter or colleague may have about an interpreter and may set important expectations. Your RID credentials can be linked easily through Credly for employers to verify. And, it is a great place to learn about interpreting industry news that may impact your practice (follow me!).

Interpreters in private practice working directly with clients should think about other aspects of branding that convey confidence in their services such as:

• Professional email address (instead of a gmail or other free service)

• An incorporated business name

• Well-designed quote and invoice templates

• Professionally written email correspondences (consider LLMs for assistance sprucing up your writing)

As with most things about our profession, the key takeaway of this discussion is to be aware and to be thoughtful. Understand what your brand is today and where you want it to be tomorrow. Think carefully about whether your actions support or detract from who you see your professional self to be. And, take meaningful steps towards an intentional tomorrow.

Sharon Grigsby Hill, Ph.D. Texas BEI Master, Medical,

Dr. Hill has been interpreting professionally for 28 years and hails from Houston, Texas. From 2011-2024, she served as the Program Director of the ASL Interpreting Program at the University of Houston. Currently, she is an Assistant Professor in the Deaf Studies program at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Her thesis is ground-breaking as it is the first mixed methods study to explore the impact of spoken African American Vernacular English (AAVE) on the work of ASL/ English interpreters. Her work explores language attitudes, perceptions, and biases regarding the usage of language variations in the field of interpretation/translation in the States. Learn more at: https://profhill.owlstown.net/

Attending conferences is invaluable to attendees, students and academics because conferences allow for intellectual and career development, face-to-face collaborations, and socializing (Etzion et al., 2022). Presenting at academic, research, or professional conferences involves significant preparation of content and performance rehearsal. Deaf academics repeatedly report on a lack of accessibility to conference content and engagement, even when the conference itself is geared towards the field of signed languages or interpretation/translation. Signed language interpreters are often a major part of leading conferences in the signed language and interpreting disciplines. This creates an inherent, but often unwanted, reliance on interpreting services for presenters and the audience. The additional time academics must use to practice or provide prep materials for the interpreting team is a source of unpaid labor, with little guarantees about whether or not effective services will be provided (O’Brien, 2020; Woodcock et al., 2007). Can this process be reimagined, minimizing the expenditure of time and energy expended by presenters and interpreters? I assert that technology can create a new paradigm.

The use of technology has typically been considered with suspicion and distrust in the field of interpreting and translation. Admittedly, machine translation or AI automation is one that has limited ability in the real-time work of live, on-the-spot interpreting. One resource, Canva, has embedded within its features the ability to use a virtual presenter or “a talking head,” to speak the written content provided in the design. Can this actually work? In January 2025, I tested this software on an international level when I prepared to deliver a stage presentation at the Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research (TISLR15) conference in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Why did I decide to use this delivery mode?

First, my research topic “Signed Language – Creating a space for Cultural and Ethnic Identity: Perspectives from a deaf expert panel when African American Vernacular English (AAVE) intersects with American Sign Language (ASL)” includes content regarding AAVE which I was unsure that the international interpreting team would be equipped to represent or discuss using current linguistic research terminology. Secondly, I was tasked with sharing the content from deaf participants in my dissertation (Hill, 2023) and I firmly believe that content should be authentically shared ASL. Lastly, in terms of my positionality, I am a Southern American Black Hearing ASL/English interpreter. I wanted nothing to intervene between the delivery of my presentation content and the global deaf audience members and colleagues who were in attendance. But the conference required that the content of my message be delivered in spoken English, Ethiopian SL, or International Sign. Being woefully underdeveloped in my International Signing skills, I pondered over the best method to deliver the content. AI technology came to the rescue!

I created a Canva presentation, trying to ensure that the key points were present on the slide. Next, I experimented with the virtual presenter apps in Canva. I chose D-ID AI Avatars to create an image of an avatar that reflected the African-American female identity that I physically represent and identify with. I then took my selected written content and copied it into the text box.

Next, I selected a US female voice; the ability to both hear the voice and to see the words spoken is an option. In total, there are approximately 60 options to choose from and these not only have a set name such as “Aria”, “Elizabeth” or “Sara” but they also have an explanation about the speaking or delivery style. For example, you can select “Sara – Friendly” or “Sara – Hopeful” or even “Sara – Shouting” for your preferred voice. The final step was to insert this video with the corresponding captions automatically created by Canva into my presentation. Voila! The presentation was complete. I would deliver my content in ASL while a parallel delivery occurred in spoken English. Interpreters would not be needed for these slides at all. There are limitations to this technology.

For hearing presenters, the ability to hear and select the voice of one’s choosing seems ideal. However, there was a distinct void of diversity in terms of regional or cultural identity. I was eager to find a voice that matched mine in sound and regional variation but there were no such options available. The only identities that exist (at the time of this writing) are: Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Kenya, New Zealand, Nigeria, Philippines, Singapore, South Africa, Tanzania, United Kingdom and United States.

For deaf presenters, the voice selection would have to be a matter of personal choice as there is no other manner for obtaining feedback regarding the voices. One thing to note: it does not necessitate the use of an interpreter. Instead, it could mean asking for a minute or two of time from a hearing family member, friend or colleague to get feedback on a few voices. The unpaid labor of preparing and sharing presentation content with an interpreter would be avoided.

Lastly, emerging technology is rarely free. Canva and D-ID are connected but you will need to buy a monthly or annual subscription plan and pay for “credits” to use the service.

Figure 2 - Picture of Dr. Hill delivering the TISLR15 signed presentation with talking avatar

Summary

Conferencing is here to stay – in person or virtually. Presenters are under enormous pressure to complete their presentations early when interpreting services are involved. AI technology creates a new way of controlling the presentation process and delivery style. Are you willing to explore it?

References

Etzion, D., Gehman, J., & Davis, G. F. (2022). Reimagining academic conferences: Toward a federated model of conferencing. Management Learning, 53(2), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505076211019529

Hill, S. G. (2023). Linguistic analysis: The impact of African American Vernacular English on the work of American Sign Language/English interpreters [Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham]. University of Birmingham Repository. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/14304/ O’Brien, D. (2020). Mapping deaf academic spaces. Higher Education, 80(4), 739–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00512-7

Woodcock, K., Rohan, M. J., & Campbell, L. (2007). Equitable representation of deaf people in mainstream academia: Why not? Higher Education, 53(3), 359–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-2428-x

Tim Riker is a Certified Deaf Interpreter and community collaborator whose work bridges artificial intelligence, language equity, and public health. As a member of the Co-SET Leadership Circle, he champions the ethical integration of AI in sign language technologies, advocating for Deaf, DeafBlind, and Hard of Hearing communities to have a voice in shaping accessible and equitable tech futures.

With over 15 years of experience in interpreting, education, and advocacy, Tim’s work spans national and local initiatives. He collaborates with the Deaf YES! Center for Deaf Empowerment and Recovery, focusing on health equity, and consults with organizations to design inclusive, community-driven solutions. Tim also serves as an adjunct lecturer in medical education at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, where he trains future clinicians to improve healthcare access and outcomes for Deaf patients.

His work has been featured in national forums on AI and language access, and he continues to bridge the gap between technology developers, healthcare systems, and Deaf communities. Tim is driven by a lifelong commitment to justice, language access, and culturally responsive innovation that centers Deaf experiences.

Ms. Sanders-Sigmon is a game changer, mentor, deaf & DeafBlind multilingual Interpreter, transliterator, writer, consultant, abolitionist, and survivor of ZOOM Culture. She believes in 360* views, ALL Justices, especially Language, Disability, Transformative, Restorative, Social, and Racial Justice. Diversity, Equity & Inclusion. Ms. Sanders-Sigmon’s lifelong aim is to dismantle all hierarchies, and while uplifting the underrepresented, underserved, also influencing those in a position of privilege. The mission? To unite and create a just environment and spaces that are fully accessible for all walks of life, in the plethora of settings that exist in our current milieu., and finally, passing on that legacy. A just legacy that is sustainable… until the end of time. Erin is a board member of Manos Unidas/Hands United and the Region 1 Representative for Mano a Mano, Inc.

Molly Glass is a Deaf professional with a strong commitment to ethical and community-centered solutions. For the past three years, she has worked as an ASL Specialist and Deaf Interpreter (DI) at Kara Technologies, contributing to innovative language access projects through signed avatar technology. She graduated college in 2010 with a B.S in Multi-disciplinary Studies and recently obtained a Certificate in Deaf Interpreting (CIDI) from Rochester Institute of Technology / NTID. In 2025, she joined the leadership team of CoSET, where they advocate for inclusive, ethical AI design that reflects the lived experiences of the Deaf community.

She lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia with her husband and two children. Outside of advocacy and tech roles, she enjoys traveling, writing, getting lost in a good book, and coffee meetups with friends.

Jeff Shaul is a builder, tinkerer, and advocate for accessible technology, born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, and now residing in Rochester, New York. He’s passionate about creating tools that serve Deaf and signing communities, combining human-centered design with cutting-edge AI to make digital spaces more inclusive. As CTO of GoSign.AI, he leads projects that bring sign languages into everyday tech, from educational games to smart home systems, ensuring the future of AI reflects the full range of human expression. With a background that bridges engineering, design, and community organizing, Jeff focuses on making innovation collaborative, ethical, and grounded in lived experience. Whether he’s prototyping new apps, scaling them up, or facilitating tough conversations about equity and tech, he brings both technological excellence and unique perspectives to every project.

In the fall of 2024, after a year of partnership with the Interpreting SAFE AI Task Force, the Advisory Group on AI and Sign Language Interpreting upgraded its name to the Coalition for Sign Language Equity in Technology (CoSET).

Currently, CoSET members are engaged in a joint organizational design process with members from the Task Force to establish a dedicated non-profit organization devoted to a collaborative mission and shared vision:

MISSION: to protect the integrity of communication between principal communicators during any interpreted interaction by developing standards for responsive AI systems and setting performance benchmarks for human-only, machine-only, and combined human+machine interpreting solutions.

VISION: that sign language and spoken language equity will be integral to the global technology landscape, and that CoSET will be recognized as an authority for setting standards, certifying technology, and advocating for the inclusion of all signed and spoken languages.

The most significant product to date is the joint Guidance on AI for Interpreting Services (July, 2024). The Guidance outlines an overarching framework to be wholly adopted or adapted to the context of use for businesses, service providers (including government) and interpreting agencies, keeping the four principles intact. The principles (listed below) provide a practical baseline for SAFE (Safe, Accountable, Fair, Ethical) technology from corporations and/or start-ups seeking to sell automated machine translation apps or platforms as a replacement for human interpreting. This is already happening with some spoken language pairs in the US, for instance, English and Spanish. The healthcare industry in particular is being intensely targeted for such translation apps. Some companies are marketing or selling “solutions” in the sign language space but none of these offer bidirectional communication. As such, they do not meet the most basic criteria for two-way, dialogical interpreting applications.

The four principles of the joint Guidance on AI anticipate possible points of confusion and clarify them in advance. These principles satisfy both SAFE AI and #DeafSafeAI for automated interpreting by artificial intelligence (AIxAI). The hashtag DeafSafeAI provides a signal that automated interpreting needs to be designed, delivered, implemented and usable by sign language users and minoritized speakers of spoken languages on par with its utility for majority language English speakers. The joint Guidance introduces the four bedrock principles and defines them, anticipating possible points of confusion and clarifying them in advance.

1. AUTONOMY for Principal Communicators (“End Users” from the perspective of tech businesses and developers). The principle of autonomy insists on the new option for communicators to Accept or Decline the use of automated interpreting, including the live option to toggle backand-forth between AI and human interpreters. Disambiguation: Accept/Decline is distinct from the way “informed consent” is used by companies to companies to document your decision to “opt in” (and use their service) or “opt out” (and not use their service) to their predetermined framework for collecting, analysing and otherwise using your data. From the standpoint of #DeafSafeAI, data usage is a distinctly second, subsidiary principle after one Accepts/Declines the use of an AI solution for automated interpreting.

2. TRANSPARENCY of quality metrics from tech companies and service providers using automated interpreting platforms and tools. This principle directs developers to reveal the relative strengths/ weaknesses of the specific language combination used by principal communicators (e.g., ASL <> English, Korean<>French, Japanese<>ASL). There should be visual indicators during use as well as plain language explanations of bidirectional capabilities.

3. ACCOUNTABILITY by tech companies for errors and harms to principal communicators. Accountability is a higher standard than the “responsible AI” movement, which sets its bar with acknowledgement on its own (not necessarily repair or remedy). The concept of responsible AI originated within the tech sector and serves their marketing goals. Accountability builds on the public safety premises of responsible AI but insists that penalties will be assessed for both systemic and individual damages to communities and persons whose communications are misrepresented or distorted by automated interpreting solutions.

4. IMPROVING SAFETY AND WELL-BEING of principal communicators and the exercise and practices of multicultural, plurilingual society by following existing laws and ethical practices about providing communication accommodations for language difference. The first three principles interlock with each other to generate real-time, embodied, real-world evidence across language communities that goes beyond legal minima to measurably improve quality of life.

Overall, the joint Guidance from CoSET and the Interpreting SAFE AI Task Force is an expression of freedom for human beings to live, work, play and innovate together with the new tools and affordances of artificial intelligence.

Since the Symposium on AI and Sign Language Interpreting at Brown University in April of 2024, CoSET members have proactively presented to groups and conferences throughout the US, and started initial conversations with allies in other countries. Dedicated presentations have been provided to Sign Language Interpreters in National Government (SLING), Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD), Consumer Access Council of the Federal Communications Commission, and the Colorado State Senate Language Access Board. Presentations have also been provided at conferences including the National Association of the Deaf, Conference of Interpreter Trainers, Orange County Department of Education Interpreters and Translators, Mid-America Chapter of the American Translators Association (MICATA), and the Globalization and Localization Association (GALA).

CoSET will be at the Deaf Academics Conference in June and the 2025 RID National conference in August.

Please engage with us on social media using the hashtag #DeafSafeAI and sign up for the CoSET newsletter at this link!

References:

Interpreting SAFE AI Task Force (July, 2024). “Interpreting SAFE AI Task Force Guidance on AI and Interpreting Services.” https://safeaitf.org/guidance/ Retrieved May 12, 2025.

Nicole Cartagna, MA, CI, CT

Nicole began her interpreting career over 20 years ago in the San Francisco Bay Area, and is now based in her hometown of New York City. Her specialization is designated interpreting in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Math) settings. Learn more at www.interpretopia.com

Inspired by the multilingualism of my native New York City and being a kinesthetic learner who already knew how to fingerspell, I started studying ASL the summer after graduating high school. That fall I started college in upstate New York about 30 minutes south of Rochester, which I was to learn in my first semester, has a Deaf college and a large Deaf population. After taking some extension courses at NTID, instead of studying abroad I spent my senior year as a visiting student at Gallaudet University. After college, I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, and a few years after that, became a proud graduate of the Ohlone Interpreter Preparation Program. I earned my RID certification in 2001 and it was around the same time that I also got a Handspring Visor, one of the first personal digital assistants, a multi-purpose mobile device.

This photo was taken after an interpreting assignment in Oakland, California, with my colleague and dear friend Cathrael Hackler. We both just bought Handspring Visors and having an electronic calendar seemed high-tech and magical. Additional features included an address book, notepad and calculator. When we started interpreting, we managed our schedules by writing out each assignment in a paper calendar. Most of our work was coordinated with agencies over the phone or on campus in the interpreter coordinator’s office. We were both interpreting a lot of post-secondary course work at the time, so they were recurring assignments. As such, we would have to tediously flip through the pages to write out the details for each week, ready at a glance. With the Visor, the device held the details. Recurring events became one entry set on repeat with an end date. Being able to sync the devices with our computers and back-up our calendars alleviated the fear of losing, or spilling coffee on, this single source of collated job details. I didn’t realize this until years later, but the adoption of this device in my interpreting practice became the catalyst for my interest in the digital revolution and its intersection with sign language interpreting.

A few years later while I was a staff interpreter at San Francisco State University, I joined the Instructional Technology graduate program there. My final project was designing instructional resources to support interpreter training programs as they transitioned their labs from analog to digital tools. My exploring new technologies to support freelance work, as well as my graduate studies focusing on digital video, led me to interpreting in the tech sector. By “tech sector” I am referring to computer science, software development, in particular, within the start-up culture of the last two decades. Interpreting for Deaf professionals in tech and coordinating designated interpreting teams has been the focus of the latter half of my career. An ongoing project that I have been working on, in various permutations over the past few years, is developing training resources for interpreting in tech. Much of my career experience in the tech sector has been working in a designated interpreting dynamic, one Deaf person with one interpreter or a small team of interpreters. I have found the book “Deaf Professionals and Designated Interpreters, A New Paradigm,” by Hauser, et al to be incredibly informative and influential in this regard. Designated interpreting in workplace settings is the reference and lens with which I am framing this essay and developing training resources.

While exploring, offering, and receiving, interpreter training experiences that focus on tech content and contexts, the focus is often on lexical items and vocabulary. I know and use at least 3 different signs for CODE on a regular basis. Learning tech related signs is interesting and important. At the same time, I would like to challenge the notion that this should be the starting point when approaching interpreting tech content. Even though we are interpreters, often in these contexts we are not technically interpreting dialogue and discussion from English into ASL, and back again. We are providing communication access services, which includes ASL-English interpretation as part of our repertoire, which is not exactly the same as providing an interpretation. Often in any workplace setting with specialized jargon, we are not just seeking a linguistic equivalent, we are considering the Deaf person’s goals, linguistic preferences, as well as other competing visual demands and inputs, since we often interpret alongside slides or other written content.

We often reference information, as opposed to translating it, adopting some of the written conventions being used, such as acronyms, copying diagrams, noting bullet points, the color of highlighted text, or a line number in code. In designated interpreting settings we apply our awareness of how the Deaf person best receives information, their background and fund of knowledge, and deliver content to them in a personalized way. We might be advised to be more lax in our interpretation when the Deaf person is attending to something else, conserving energy and attention for when the conversation is directed to the Deaf person or their topic of interest. We employ their preferred lexicon, in contrast to interpreting for a general audience or someone for the first time.

When I have coordinated interpreting teams in tech contexts, I noticed a trend in the resumes I reviewed, that ASL-English interpreters tend to have liberal arts educational backgrounds. I also notice this amongst my teams in the tech sector in general. I am very interested in exploring if there is any evidence to my anecdata. If this is the case, when working with technical content it can be more difficult to draw upon our own fund of knowledge as we might in other contexts. In many tech employment settings, interpreters are also working as independent contractors with limited opportunity for explicit instruction or training. As an approach to interpreting in these contexts and this content, I propose a narrative approach that focuses more on discourse and less on lexicon. I think there is a tendency for interpreters to become overwhelmed with the fast pace of computer science terminology being spoken. The goal of my approach is to reduce overwhelm by capitalizing on our human tendency to categorize inputs for cognitive efficiency, improving our ability to listen for the story. In focusing on lexical items, we might overlook the “story of tech,” Despite the vast diversity of tech contexts and

workplaces, I propose that most “tech talk” touches on one or more of the following categories: Time, Change, Power, Code, Data, and Network.

Technology can be defined in several ways. I succinctly define technology as the development and diffusion of tools and innovation over time. Technology changes. Software and hardware are under continuous development, from Version Now to Version Next, for example, iPhone 15 to iPhone 16. Power is expressed in various ways in the tech industry, from practical elements such as how we power our tech devices, source components, make batteries, and cool servers, to power dynamics that lead to mass layoffs, and the way the tech industry can influence politics and policies about tech usage. Most importantly: Who has the power to decide what gets developed, how, and where? Much of contemporary tech is made with code. Some code and development tools have signs that have been adopted, like Python being signed as “snake,” and Kubernetes signed following the written abbreviation “K8”. Meetings that are interpreted in tech contexts are often reviewing an aspect of the software development lifecycle (SDLC), the changing of code over time. Code is used to collect data How data is collected, stored, shared, and represented is the subject of much debate and varies around the world. Data is also considered a contemporary currency, and enterprise decisions are expected to be “data-driven.” People, and data, arranged and connected to each other form networks and the internet is a global network. Artificial intelligence systems are actually networks of large language models. Like most professions, it’s developing one’s personal networks that are crucial to getting work in the tech sector as well.

I propose we approach our work by: preparing, listening, interpreting, and reflecting. When preparing for a tech related assignment, reviewing videos online of Deaf people signing about tech content is one of the best resources. Over the past few years, major tech companies announcing new products or features have increasingly included ASL interpretation or interpreted versions of their presentations. Watching these recordings is a great way to get tech information in both English and ASL. Deaf developers are also making vlogs and video podcasts, for example the vlog “Deaf in the Cloud.” The Atomic Hands website has a page that lists various STEM sign resources. I frequently reference ASLCORE.org for STEM related ASL signs and explanations.

As part of the interpreting process, I propose listening “from the outside in,” focusing less on the novelty of the lexical items and more on the relationships between elements. What is the problem this team or company is trying to solve? What was the previous way and what is the new approach? Who are the cast of characters involved? Considering these questions can help us listen for the story and approach our use of space in our interpretations. Interpret considering the goals of the communication and the Deaf person’s additional visual demands and inputs. Throughout the interpreting process we reflect on our work and choices. Developing a practice of having a place where these thoughts go can be supportive and informative. Perhaps it is the latest handheld digital device, or a classic analog notebook. Regardless of the tool or approach, strive to share these reflections to further expand your skill set and horizons.

RID’s purpose is to serve equally our members, profession, and the public by promoting and advocating for qualified and effective interpreters in all spaces where intersectional diverse Deaf lives are impacted.

RID understands the necessity of multicultural awareness and sensitivity. Therefore, as an organization, we are committed to diversity both within the organization and within the profession of sign language interpreting.

Our commitment to diversity reflects and stems from our understanding of present and future needs of both our organization and the profession. We recognize that in order to provide the best service as the national certifying body among signed and spoken language interpreters, we must draw from the widest variety of society with regards to diversity in order to provide support, equality of treatment, and respect among interpreters within the RID organization.

Therefore, RID defines diversity as differences which are appreciated, sought, and shaped in the form of the following categories: gender identity or expression, racial identity, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, Deaf or hard of hearing status, disability status, age, geographic locale (rural vs. urban), sign language interpreting experience, certification status and level, and language bases (e.g., those who are native to or have acquired ASL and English, those who utilize a signed system, among those using spoken or signed languages) within both the profession of sign language interpreting and the RID organization.

To that end, we strive for diversity in every area of RID and its Headquarters. We know that the differences that exist among people represent a 21st century population and provide for innumerable resources within the sign language interpreting field. M V V

RID is the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and is a professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting.

We envision qualified interpreters as partners in universal communication access and forwardthinking, effective communication solutions while honoring intersectional diverse spaces.

The values statement encompasses what values are at the “heart” or center of our work. RID values:

• the intersectionality and diversity of the communities we serve

• Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging (DEIAB)

• the professional contribution of volunteer leadership

• the adaptability, advancement and relevance of the interpreting profession

• ethical practices in the field of sign language interpreting, and embraces the principle of “do no harm”

• advocacy for the right to accessible, effective communication

Anna Dunbar, NIC

Mckenzie Dowling, NIC

Leah Lishman, NIC

Megan Malzkuhn, CDI

Tiffany Nowicki, NIC

Jayha Smith, NIC

Kalyna Sytch, NIC

Nicole Tyler, NIC

Danielle Whelan, NIC

ME NJ NY MA NY NY NY PA NY

Gabriella Blankenship, NIC

Darcy Boos, NIC

Daniel Dall, NIC

Tabatha Fratangelo, NIC

Chasah Greene, NIC

Jacqueline Harris, NIC

Amanda Jones, NIC

Christina Ogdie, NIC

Isabel Sevilla, NIC

Rachel Smith, NIC

Hector Torres-Betancourt, NIC

LaTarra White, NIC

Jaden Hill, NIC

Alyssa McCann, NIC

Katrina Montoya, NIC Region IV

Taylor Bajumpaa, NIC

Riley Brannan, NIC

Olivia Culkar, NIC

Zachary Harker, NIC

Kaylea Longendyke, NIC

Abigail Mattingly, NIC

Chazz Middlebrook, NIC

Laurie Waldeck, NIC

Patricia Wheatley, NIC

Elliott Aronson, NIC

Christa Griffiths, NIC

Chelsea Hull, NIC

Scott Keller, CDI

Andrea Luikart, NIC

Timothy Mills, NIC

Andrew Moore, CDI

Kassandra Romo, NIC

Sara Smith, NIC

Jami Stirewalt, NIC

Caroline Wolf, NIC

Maintain current RID membership by paying annual RID Certified Member dues.

FY2025 Reinstatements for revocations that occurred due to non-payment of Certified membership dues and failure to meet the CEU requirements for a certification cycle found here. Membership

• 8.0 total CEUs

• 6.0 Professional Studies (PS) CEUs

• A minimum of 1.0 in PPO training

• Up to 2.0 General Studies CEUs

Should a member lose certification due to failure to pay membership costs or failure to comply with CEU requirements, that individual may submit a reinstatement request. The reinstatement form and policies are outlined here.

Adhere to the RID Code of Professional Conduct and EPS Policy.

FY2025 Revocations for revocations that occurred due to non-payment of Certified membership dues and failure to meet the CEU requirements for a certification cycle can be found here

Revocations due to EPS violations can be found here.

RID Certified members who decide to voluntarily relinquish the RID certification(s) they currently hold are required to submit a completed, signed and notarized form. To learn more about the eligibility requirements or to submit your request to voluntarily relinquish the RID certification(s) you currently hold, click here. This form is required to be notarized.

Decision Date: 3/26/2025

Member Name: Andrea Jean Oberst

CPC Tenet Violations Found:

Tenet 1. Confidentiality

Tenet 2. Professionalism

Tenet 3. Conduct

Tenet 4. Respect for Consumers

Tenet 5. Respect for Colleagues

Tenet 6. Business Practices

EPS Policy Violations Found:

EPS Policy II. Relating to Upholding Trust in the Profession.

1. Confidentiality Transgressions (a)

3. Actions Taken During Interpreting-Related Activities (a, i, & m)

5. Disrespect for colleagues, consumers, organizational stakeholders, and students of the profession (b & d)

Sanctions: Certification Revoked, Membership Terminated. May reestablish eligibility for certification and/or membership after two years from the decision date. An application to regain eligibility for certification or membership must include satisfactory evidence demonstrating an understanding of how conduct affected individuals and systems.

Decision Date: 4/14/2025

Member Name: Charlotte Saguibo

CPC Tenet Violations Found:

Tenet 7. Professional Development

EPS Policy Violations Found:

EPS Policy I. Relating To The Integrity Of Membership And Credentials

2. Committing fraud in the CMP process (c)

Sanction: Certification Revoked. Ineligible for cycle extension. Ineligible for certification reinstatement.

Calling all authors! Do you have insights, anecdotes, research, or training on topics related to ASL Interpreting? We want to work with you!

Submit by: August 15 Current Trends

Summer 2025

Connections & Reflections

Fall 2025

Submit by: November 3

After receiving your submission, the VIEWS Board of Editors will review the article and provide feedback. You will collaborate with the VIEWS Editor-in-Chief to address the feedback and ask any questions during the review process. Once the English version of the article is finalized, you will submit your ASL version, and we will handle the rest!

Submit Your Article Here!

With over 13,000 members in the U.S. and abroad, RID is the largest, comprehensive registry of American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters in the country! Connect and communicate with your potential and existing clients through our exclusive, digital magazine VIEWS, offering fresh and relevant content every season. Reach your marketing goals by connecting with our VIEWS audience for your company or organization’s events, promotions, job announcements, webinars and more!

VIEWS, RID’s digital publication, is dedicated to the interpreting profession. As a part of RID’s strategic goals, we focus on providing interpreters with the educational tools they need to excel in their profession. VIEWS aims to inspire thoughtful discussions among practitioners by providing information about research and insight into various specialty fields in the interpreting profession. With the establishment of the VIEWS Board of Editors, the featured content in this publication is peerreviewed and standardized according to our bilingual review process. VIEWS utilizes a bilingual framework to facilitate knowledge sharing among all parties in an extremely diverse profession. As an organization, we value the experiences and expertise of interpreters from every cultural, linguistic, and educational background. We aim to explore the interpreters’ role within this demanding social and political environment by promoting content with complex layers of experience and meaning.

VIEWS publishes articles on matters of interest and concern to the membership. Submissions that are essentially interpersonal exchanges, editorials or statements of opinion are not appropriate as articles and may remain unpublished, run as a letter to the editor, position paper, or column. Submissions that are simply the description of programs and services in the community with no discussion may be redirected to the advertising department. Articles should be 2,000 words or fewer. If you require more space, the article may be broken into multiple parts and released over consecutive issues. Unsigned articles will not be published. RID reserves the right to limit the quantity and frequency of articles published in VIEWS written by a single author(s). Receipt by RID of a submission does not guarantee its publication. RID reserves the right to edit, excerpt or refuse to publish any submission. Publication of an advertisement does not constitute RID’s endorsement or approval of the advertiser, nor does RID guarantee the accuracy of information given in an advertisement. Advertising specifications can be found at https://rid.org/about/advertising/, or by contacting advertising@rid.org.

Please submit your piece using the submission form found here. All submission and permission inquiries should be directed here.

VIEWS is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Statements of fact or opinion are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinion of RID. The author(s), not RID, is responsible for the content of submissions published in VIEWS.

VIEWS (ISSN 0277-7088) is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Materials may not be reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without written permission. Contact publications@rid.org for permission inquiries and requests.

VIEWS’ electronic subscription is a membership benefit and is covered in the cost of RID membership dues.

Brooke Roberts, VIEWS Editor-in-Chief

Elisa Maroney, PhD, CI & CT, NIC, Ed:K-12

Stephen Fitzmaurice, Ph.D., NIC:A, CI/CT, NAD 4, Ed:K-12

© 2024 Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. All rights reserved.