THEORETICAL IMPERATIVE

INTRODUCTION

“Toronto is getting older. For the first time in history, there are now more Torontonians over the age of 65 than children aged 15 and under. Looking ahead, the number of people in Toronto aged 65 and over is expected to almost double by 2041.”1

Toronto’s senior population is growing, and with it, the need to keep older persons healthy, active, and participating in their community. Nearly 70,000 seniors in Toronto have low incomes and housing affordability is a serious issue for seniors.2

There is a pressing need for affordable, active, walkable, transit-oriented senior housing across a variety of levels of care. This includes full-time care, informal retirement communities, and housing developments that house a high concentration of seniors. The senior population is growing and has a diverse set of needs, including aging in place, access to services, amenities, transportation, and work opportunities.

1 Austen, Andrea. 2018. ‘Toronto’s Senior Strategy 2.0’. City of Toronto.

North America’s built and natural environments are fraught with crises. The climate crisis, the housing crisis, the cost of living crisis, and both the health and healthcare crises. Radical change is required in the fields of Architecture and Urban Planning as the current system of constructing new housing and services is failing to address or mitigate these crises as a deeper societal problem; these crises do not have an expiration date. They are continuously inherited by the next generation, and so multigenerational design must be employed to produce lasting solutions. There are significant health impacts of the housing crisis at the macroscopic scale in terms of urban planning especially through zoning, and at the microscopic scale through building types, construction materials, and the use of green space.

Suburban sprawl creeps further into natural areas and farmlands in the name of growing the housing supply, but in so doing, also introduces negative externalities like the reduction of natural vegetation and productive farmland.3 The loss of forest and farmland is a permanent loss that has permanent and devastating effects on the environment and the health ease or dis-ease continuum. The suburbs built on this land are characteristically composed of cookie-cutter detached homes with a fenced-off backyard and a pristine Kentucky bluegrass lawn. Despite the significant ‘green’ area afforded per resident for front yards and backyards, few species are allowed to grow or survive here, and this requires significant maintenance and fresh water to upkeep. This is also reflective in the building materials and infrastructure needed for suburbs that are energy intensive, non-renewable, and carbon intensive. 4

This reflects a very human-centric design that is pervasive throughout North America, where individualistic thinking dominates a collective well-being. Often suburbs are seen as “healthy” places but are by no means healthy for the environment, more so than dense urban environments.5 The causes of suburban sprawl and emigration from cities into suburbs are numerous but this paper is focused on one; the desire to live in a healthy environment. Seniors especially tend

2 Canadians for a Sustainable Society. ‘Farmland Loss in Canada: The Alarming Impact of Urbanization’. Accessed 3 October 2024. https://sustainablesociety.com/research-material/farmland-loss/.

4 Jones C, Kammen DM. Spatial distribution of U.S. household carbon footprints reveals suburbanization undermines greenhouse gas benefits of urban population density. Environ Sci Technol. 2014 Jan 21;48(2):895-902. doi: 10.1021/es4034364. Epub 2014 Jan 2. PMID: 24328208.

5 Ibid.

to leave dense urban areas for more quiet suburban areas that may manifest an ideal fantasy borne from the nuclear household in a safe and healthy neighborhood. This desire is not new, and throughout history these qualities have been found outside the dense and often polluted city. The reality is that there is no longer enough space in Ontario to continue building these space-inefficient neighborhoods and these suburbs do not possess the density to provide adequate amenities and health services for an aging population without driving for several hours.

Architects and Planners must be creative and develop both housing and healthcare facilities in urban areas and there are design principles and interventions that can make urban spaces healthier and offer Seniors a real alternative to traditional car-centric suburban living.

Where segmented planning produced sprawling, single-use postwar suburbs that demanded every trip be taken by car, holistic design must now produce extreme mixed-use housing and health infrastructure that is surgically inserted into underutilized land in amenity-rich and walkable urban environments.

Urban environments need not be unhealthy, in fact they can be healthier than suburban or rural environments, but this takes a deep understanding of what it means to be healthy and stay healthy.

Salutogenic design is a preventative approach to healthcare, using environmental design considerations that contribute to healthy spaces like promoting air quality, daylight, sound, visual stimuli, and natural elements. Salutogenic design in urban areas may then provide a sustainable antithesis to suburban developments such that there are healthy places to live within the city; this begins with diagnosing the primary sources of urban unhealthiness. Historically, the lack of zoning laws permitted overcrowding and pollution in residential areas which led to the reaction

of separating land uses and utilizing personal vehicles to travel from one zone to the next. This is a sensible and rational concept except for the detrimental consequences associated with a city’s over-reliance on cars.

Car-centric design leads to significant air pollution, sound pollution, light pollution, and ground pollution, and significant resources are required for roads, parking lots, and safety features like elevated curbs and bollards. These material resources are expensive, carbon-intensive, and require significant maintenance, but the resources associated with land use are the most detrimental. The scale of car-centric infrastructure spreads the city apart, and makes walking to activities or services uncomfortable, unsafe, or impossible. These services include public transit and healthcare facilities which often cannot provide equitable access due to low population density. This means that an older person or someone with specific health needs may need to move from their home to access the healthcare services they require.

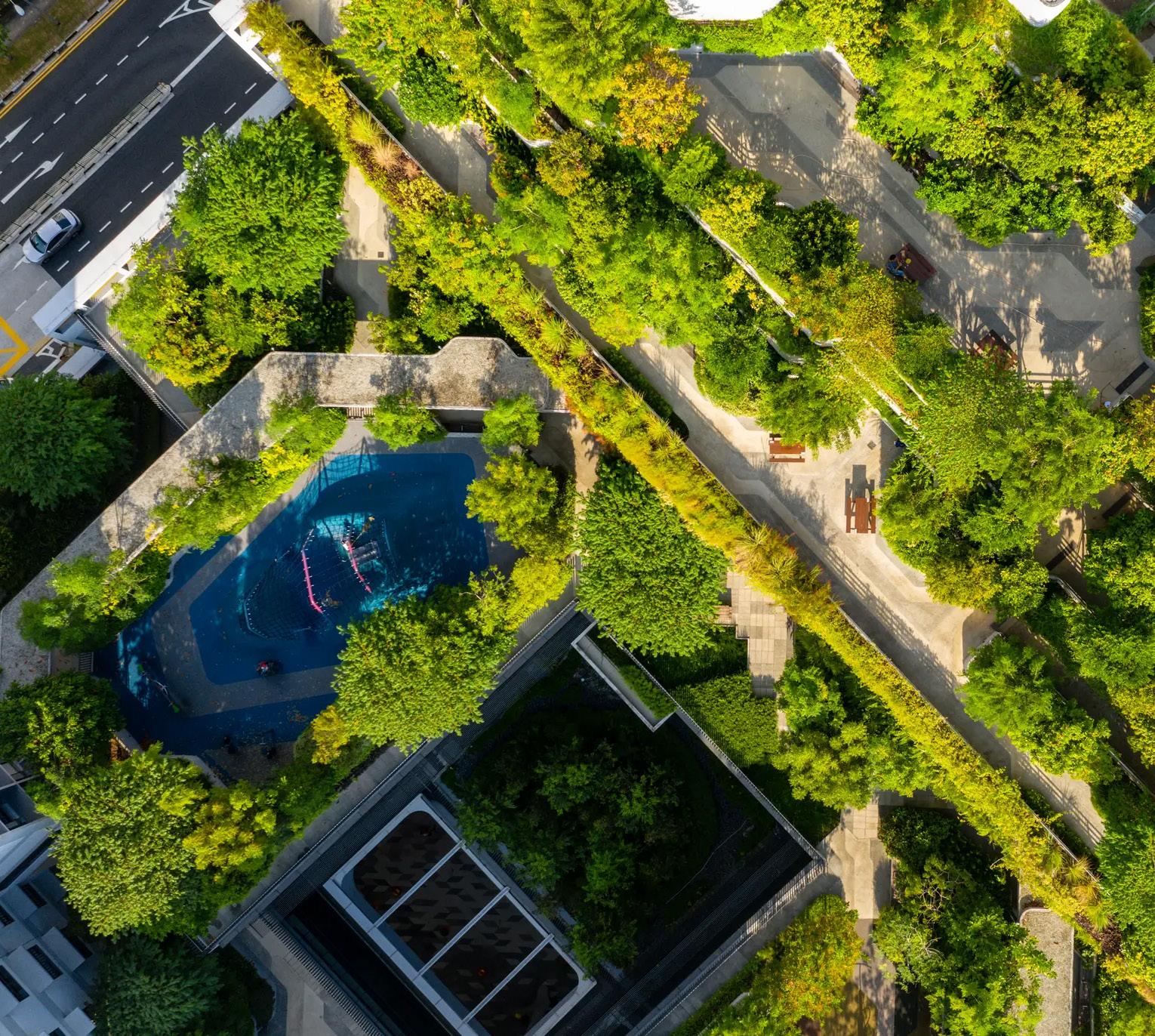

Urban and high-density areas with lower access to natural spaces are especially at risk of spreading pathogens and exposing communities to unhealthy environments like those affected by pollution. These artificial spaces are often car-centric spaces, designed for transportation rather than for people and have displaced native flora and fauna for the construction of concrete and asphalt surfaces that heat up cities.

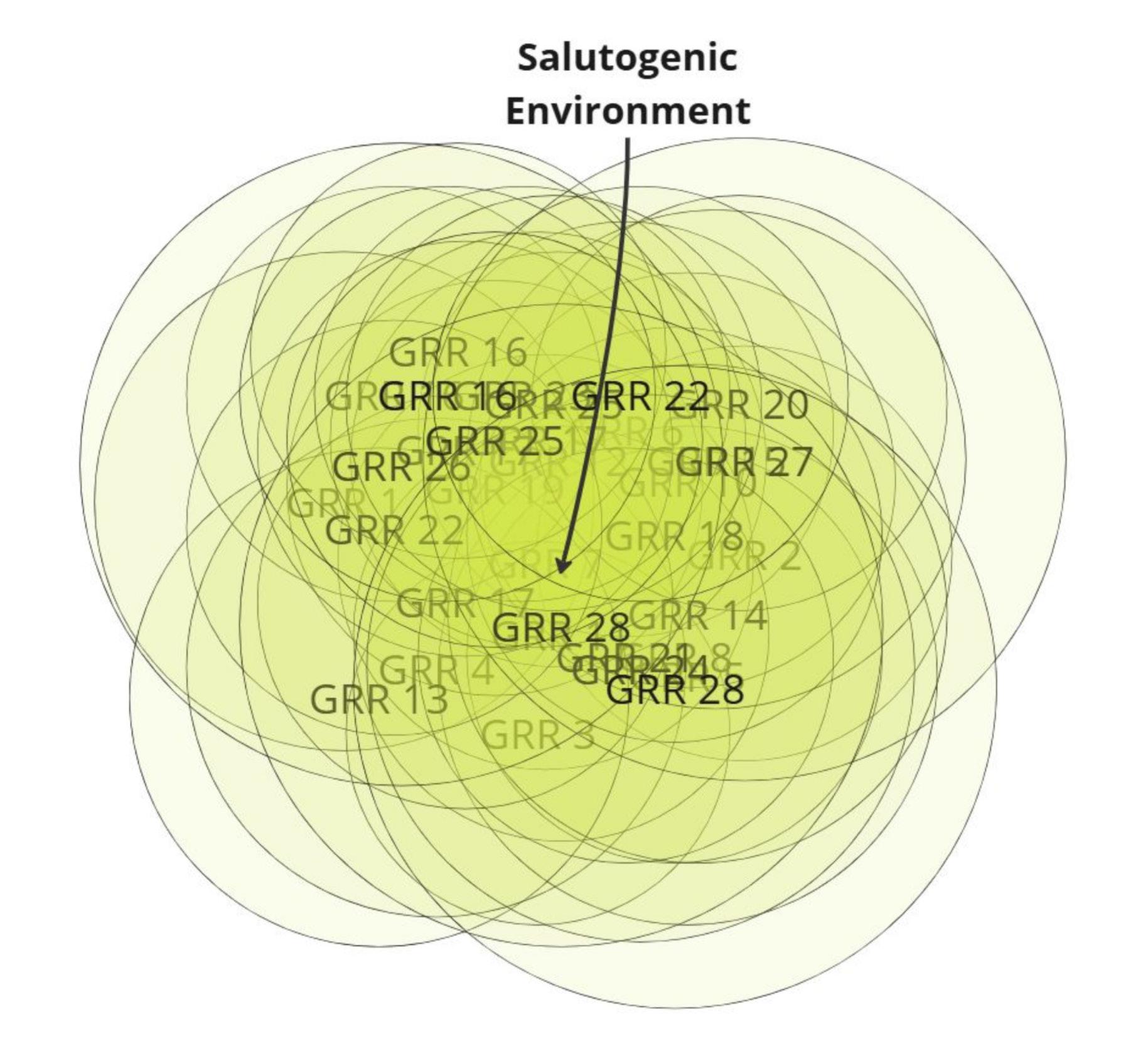

At the city and block scale, the Handbook of Salutogenesis states several methods for integrating salutogenic design into urban environments beyond these environmental design concepts like incorporating a strong sense of coherence (SOC). This term describes the relationship between one’s understanding and experience of a place through qualities such as comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningful -

ness.6 These qualities are produced through resources such as design elements, decorations, or spaces like streetlights or a forested park. A strong sense of coherence is then linked to positive health outcomes through behavior, like the increase in access to nature, physical exercise, or social interaction through the use of a walkable, charming, tree-lined street. Salutogenic design may specifically be used to improve the quality of disadvantaged and health-deprived social groups by determining which resources they desire and improving the quality of those resources. This method of connecting health outcomes of a social group to physical design elements is rational and relates to an aspect of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), where a person’s understanding of the world and of themselves is built on their relationships to recognizable objects; like the resources described by Antonovsky.7 The ability to understand and describe something makes it a comprehensible object with which one can develop a meaningful relationship, this is the root of the comprehensibility and meaningfulness aspects of a strong SOC. This concept extends beyond the limits of salutogenic design and openly rejects the superiority of humans over nonhumans, where all things possess interrelationships and exist in interconnected systems. Posthuman salutogenic design must then be a preventative approach for a healthy world where all beings are given equal consideration, concepts from permaculture design may improve the efficacy of posthuman salutogenic design. Rural areas have aspects of salutogenic design like greater access to nature and reduced pollu -

6 Mittelmark, Maurice B, Georg F Bauer, Lenneke Vaandrager, Jürgen M Pelikan, Shifra Sagy, Monica Eriksson, Bengt Lindström, and Claudia Meier Magistretti. 2021. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. 2nd ed. Cham: Springer Nature.

7 Harman, Graham. 2018. Object-Oriented Ontology : A New Theory of Everything. UK: Pelican an imprint of Penguin Books.

tion from cars, but farms may in fact be unsustainable and pollute their environment.8 In fact, the growth of industrialized monoculture farmlands is problematic due to significant negative externalities including biodiversity loss, excessive use of pesticides and artificial fertilizers and the ensuing run-off, as well as monocrops’ precarious susceptibility to diseases and pests.9 10 Car-centric urban planning and low-density suburban sprawl must be reconsidered to make urban areas healthy and reduce the land required to house growing populations.

Permaculture is a system that incorporates ecological design, whole systems thinking, and posthumanism to craft productive, biodiverse, and resilient ecosystems. This is antithetical to both the fenced-off Suburban lawns and the chemical monoculture that dominate Ontario’s environment. Resilient ecosystems are designed on homesteads to provide a sustainable, self-sufficient life for the people and animals living on that land. Agriculture, horticulture, polyculture, silviculture, apiculture, fungiculture, aquaculture, agroforestry, microbiology, waste management, water management, rhizophagy management, renewable energy systems, and community involvement are all components of a permaculture system that are employed with practical principles. These principles serve to simplify the complexity of an ecological design, and include observing and interacting with the local environment, catching and storing energy, using renewable resources, producing no waste, applying patterns from nature into design, integrating rather than segre -

8 Kremen, Claire, and Albie Miles. “Ecosystem Services in Biologically Diversified versus Conventional Farming Systems: Benefits, Externalities, and Trade-Offs.” Ecology and Society 17, no. 4 (2012). http://www.jstor.org/ stable/26269237.

9 Kelsey, Jason. Environmental Science: An Evidence-Based Study of Earth’s Natural Systems. Muhlenberg College, 2023. https://jstor.org/stable/community.35644891.

10 Macleans. ‘How Crop Monocultures Are Threatening Our Food Supply’, 2017. https://macleans.ca/society/how-crop-monocultures-are-threateningour-food-supply/.

gating, incorporating diversity, and making the most of feature edges.

The practical application of connections, relationships, patterns, and energy flows are crucial to this system of thinking. For example, a core element of permaculture is the use of guilds, these are groups of tree, plant, shrub, animal, and insect species that have synergistic relationships. These associated, interconnected species would be placed together in clusters in an appropriate location on a site relative to its environment. Guilds like the apple tree guild would typically include one or several fruit trees at its centre, surrounded by smaller trees or shrubs with shade-tolerant plants or vegetables under the tree canopy. A complete environment is produced in each guild, with native and non-native but non-invasive species, abundant edible vegetation like fruits or vegetables, nitrogen fixing trees or plants, pollinators, mulch crops, cover crops, weed suppressant, dynamic root accumulators, plants that repel or attract insects or animals, vegetation that provides clothing or material, and others that have medicinal properties.

With farmlands being pushed further from city centres, and an aging and shrinking population of farmers and farmland, the urban application of permaculture provides a solution to many problems including labor shortage, refrigerated supply chains, transportation, land use, underutilized urban spaces, access to grocery stores, and biodiversity. The access to nature demanded in salutogenic design can be provided through environments surrounded with urban permaculture. There are not only spatial and experiential synergies between urban salutogenic design and urban permaculture, but also therapeutic synergies from horticultural therapy. It has been shown that hands-on farming is therapeutic and provides mental health benefits, connection to nature, heliotherapeutic benefits, physical exercise, and community and social interaction like at Dutch Care Farms or Green Care Farms.11 Salutogenic, community-centric urban environments that integrate permaculture can provide net-positive impacts rather than just net-zero.

This design thinking can extend into the architectural design and structural design of the built environment, and utilize the principles of regenerative architecture like ecosystem-centric design, circular economies, and disassembly-driven design;12 specifically using renewable, non-toxic, carbon-storing, ma11 Green Care Farms Inc. ‘Research on Care Farms’. Accessed 3 October 2024. https://www.carefarmscanada.com/research.

12 ‘Five Key Principles in Designing Regenerative Buildings | U.S. Green Building Council’. Accessed 3 October 2024. https://www.usgbc.org/articles/ five-key-principles-designing-regenerative-buildings.

terial efficient mass timber construction modules that integrate urban farming and salutogenic design.

Buildings can and should use modular construction, locally grown building materials, possess communal spaces to grow food, and incorporate environmental design that keeps people healthy. Sustainability is no longer adequate in an imperiled world, architectural design must enact regenerative design principles to cultivate appropriate buildings. Buildings must reduce operational carbon through the use of tight air barriers, appropriate insulation, exterior shading, and natural ventilation that is appropriate to the climate. Using grown, biogenic building materials that store carbon like stick frame wood, hemp insuation, and mass timber can contribute to a building’s regenerative qualities by reducing embodied carbon and increasing carbon sequestration.

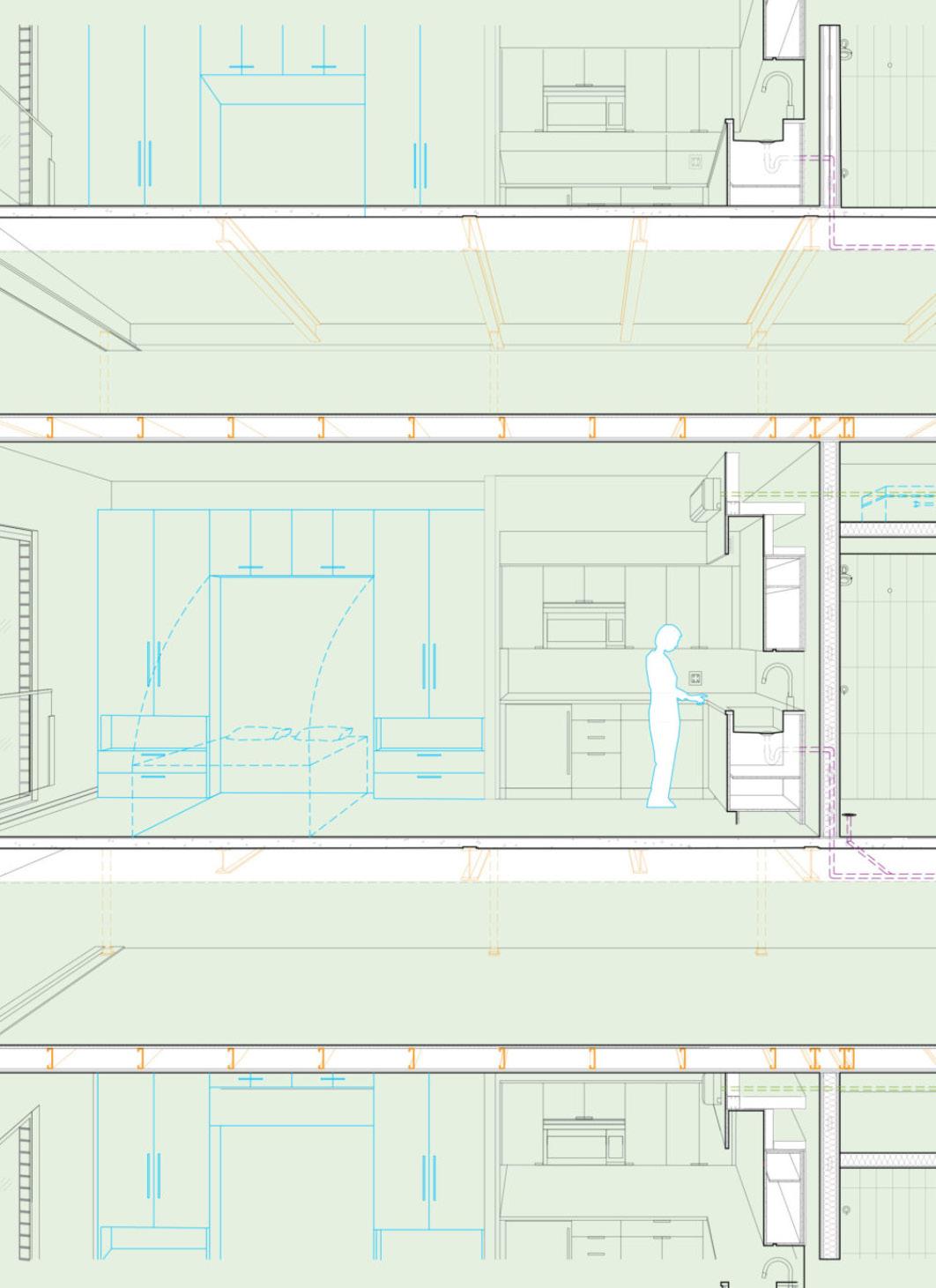

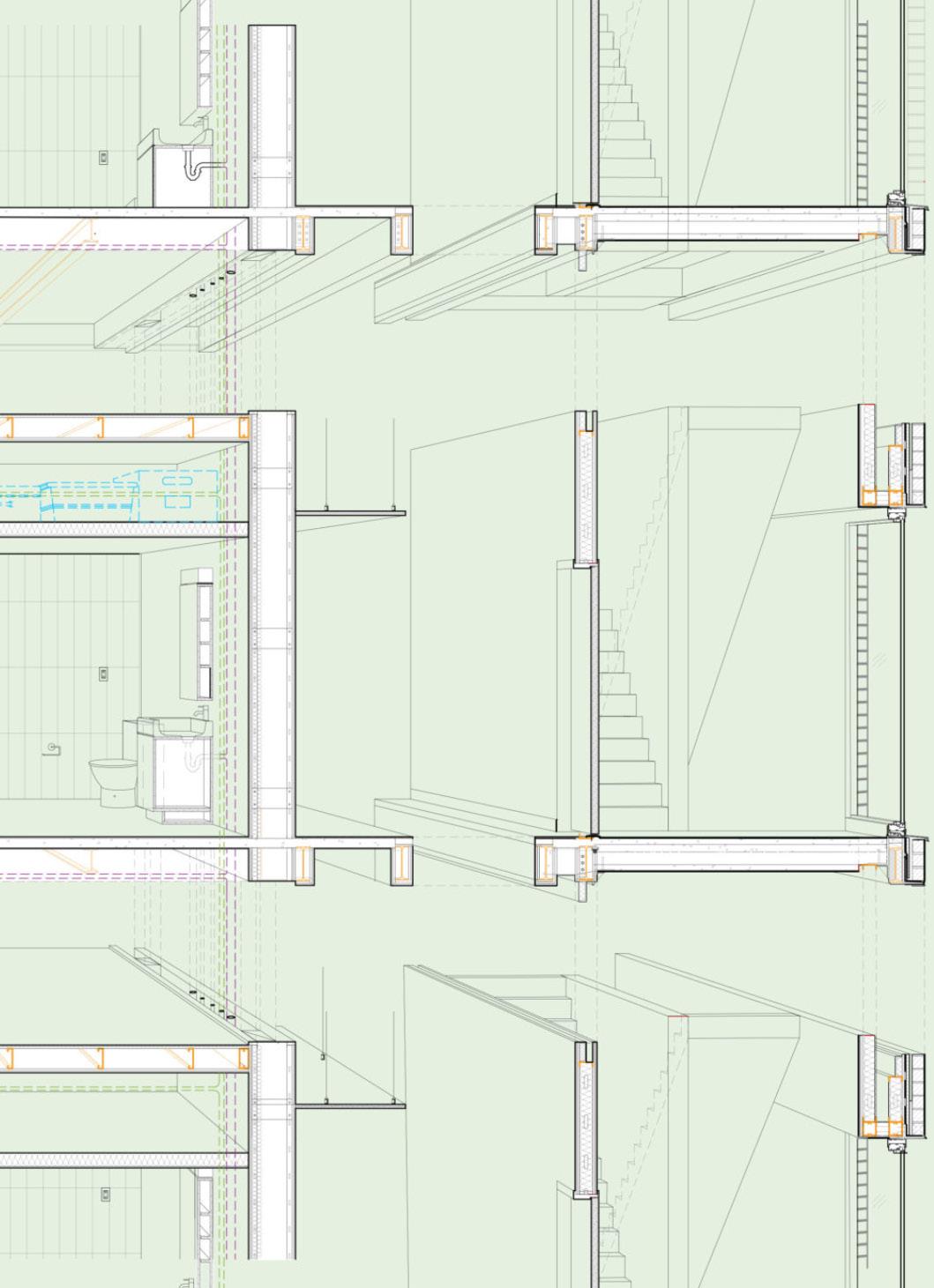

Designing for disassembly and repair is another key aspect to extend a building’s life and reduce the embodied carbon associated with construction materials. The ability to reuse biogenic building materials as modules is a regenerative principle that is growing in popularity. In the context of Toronto, Assembly Corp and Element5 are leading manufacturers and designers of prefab mass timber modules.13 These designs necessitate complete collaboration between designers and manufacturers and are becoming increasingly refined, tailored to different programs, and applied to many types of projects including new builds, renovations, and historical building additions.

Prefabricated construction can provide more affordable housing faster than any other construction method with better quality control and working environments. The use of mass timber and stickframe building elements is well suited to modular 13 Assembly Corp. ‘Projects’. 2024. https://assemblycorp.ca/projects/.

construction, and includes low embodied carbon and carbon sequestration. There are complications and limitations to both modular construction and wood construction like fire, acoustic, structural, but these can be addressed through creative design solutions. “In general, timber requires less equipment and workmanship compared to concrete and steel. This makes timber structures much simpler when they are well planned. [...] However, reducing the percentage of timber used in the building in turn reduces its potential benefits. Timber has other benefits compared to concrete and steel including its aesthetic appeal, opportunities for sustainable supply chain when supplied from all over Canada, less embodied energy and carbon emissions, and quicker erection.Also, it has opportunities for prefabrication which increases the construction accuracy and productivity, reduces on-site construction time and waste, and allows for concurrent off-site work to occur in controlled conditions. In addition, the light weight of timber makes it more suitable for building modules for modular construction compared to concrete.”14

Car-centric environments like sprawling suburbs, farmlands, and city peripheries are often polluting and unhealthy; they are insulated from their negative externalities on the local environment and the planet as a whole, but it is possible to move toward a posthuman environment immersed in nature, walkability, and community. Salutogenic design principles and horticultural therapy augmented through the lens of permaculture can provide healthier spaces for humans and nonhumans alike.

14 Dorrah, Dalia H., and Tamer E. El-Diraby. 2019. ‘Mass Timber in HighRise Buildings: Modular Design and Construction; Permitting and Contracting Issues’. Modular and Offsite Construction (MOC) Summit Proceedings, May, 520–27. https://doi.org/10.29173/mocs134.

Project Scope and Goals

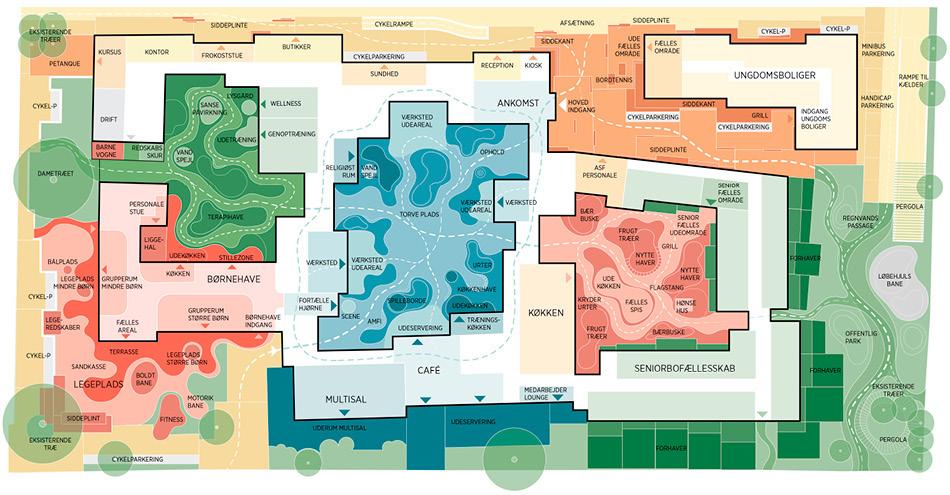

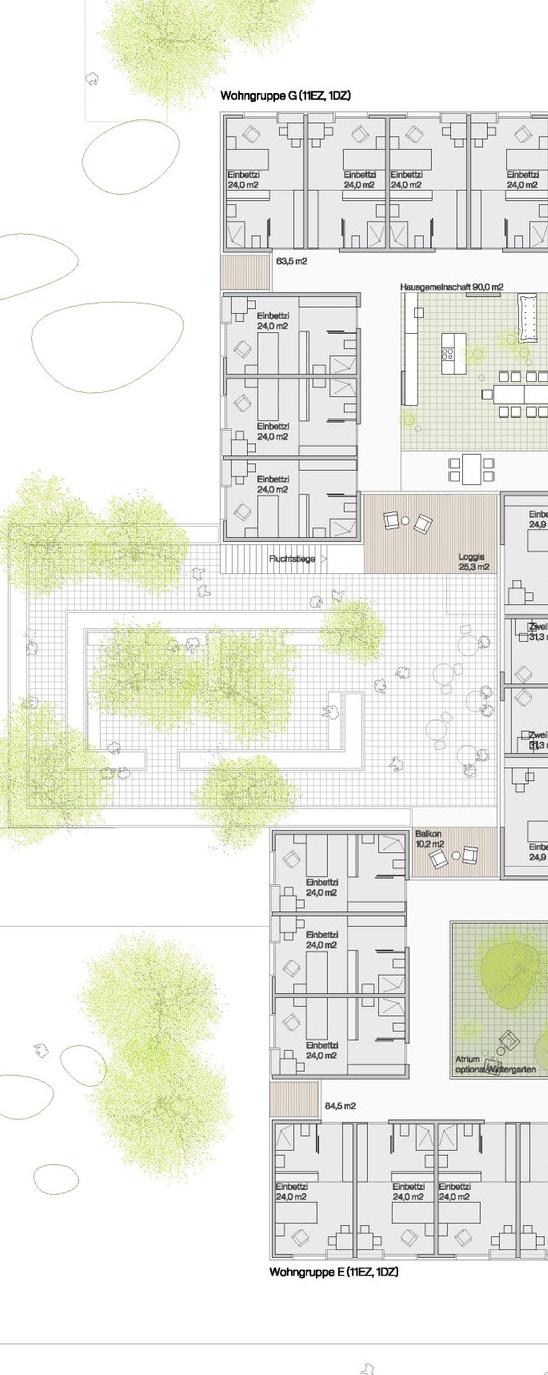

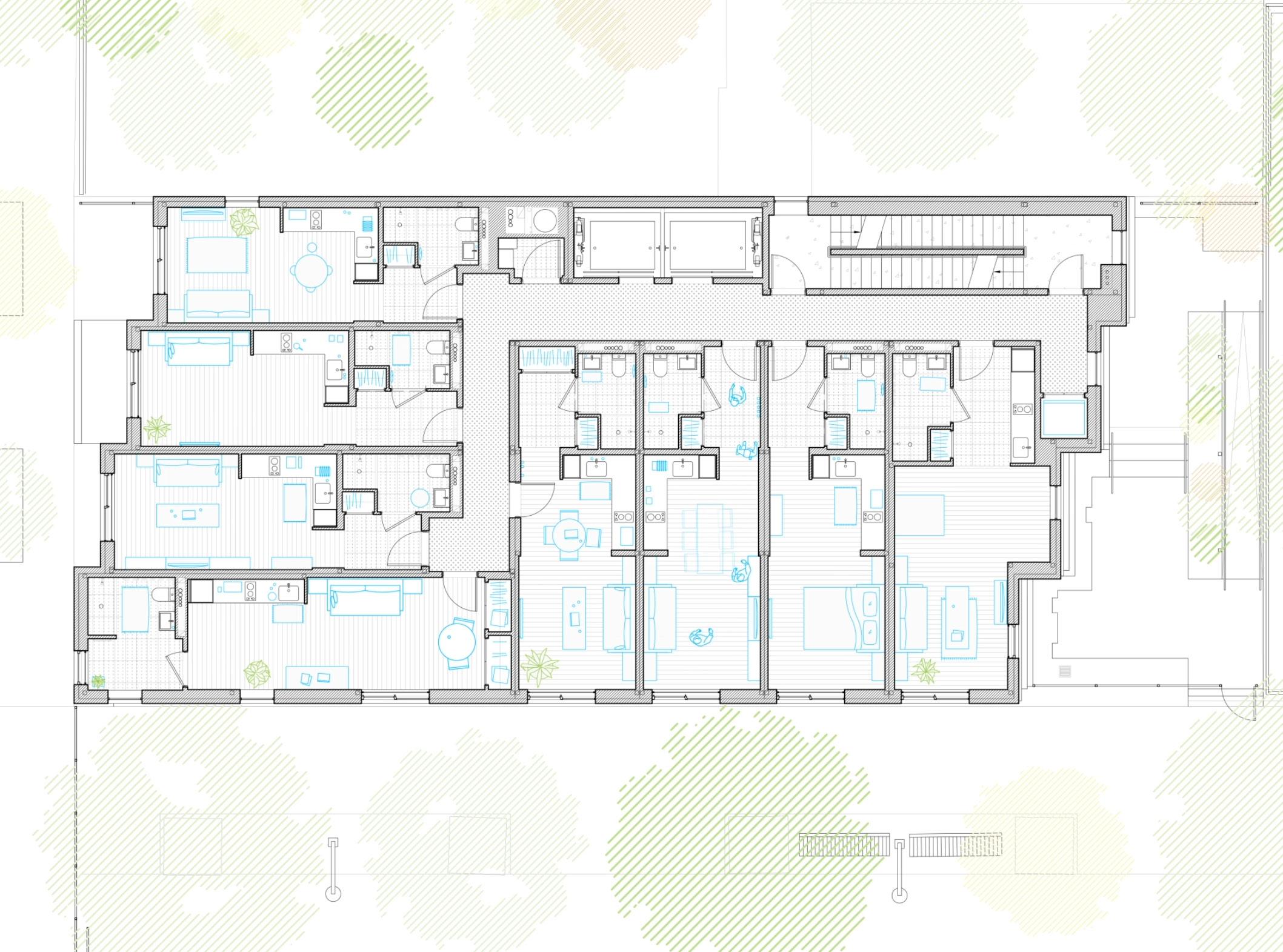

To design a mixed-use high-rise long term care facility with 192 Dementia Care beds designed using salutogenic principles with amenities specific to agrotherapy, intergenerationality, and community.

The building is to be built predominantly from biogenic materials using cost-efficient modular and panelized prefabrication.

Toronto has a pressing and immediate need for long-term care. The population over 80 is projected to more than double between 2023 and 2040 but there are not even enough beds to support the current population. In fact, more than 45,000 people in Ontario are waiting for long-term care and this waitlist has doubled over the past 10 years. Additionally, more than 3 in 4 residents entering long term care facilities require high levels of care but most caregivers cannot handle all of their duties and nearly half have reported distress in 2022-2023. Across Canada, staff vacancy rates increased by 70% in only four years and now twice as many workers are needed including Nurses and Personal Support Workers are. This is a crisis in healthcare infrastructure but should be framed as an opportunity rather than a problem. As of 2024, long-term care provides 173,751 jobs and contributes $12.43B to GDP; should the government fulfill their commitment to build 58,000 long term care spaces, an additional 59,000 jobs and $37B to GDP is projected.1

These statistics highlight a significant demand for long-term care but also a deeper systemic demand to keep people healthy, especially as they get older and become more at risk of age-related diseases. Patients often have multiple diseases and can develop further diseases during their time in long-term care. Various studies indicate that there are salutogenic or therapeutic approaches to all of these diseases through the use of gardening/horticultural therapy, community participation, healthy eating, and other biophilic or salutogenic environments. According to Alzheimer’s Society of Canada, Ontario has by far the most projected cases of dementia in Canada and the number of new cases and total cases is growing substantially.2 A summary from Toronto’s 2023 Population Health Profile indicates Torontonians are aging and increasingly diverse, negatively impacted by the effects of an increasingly expensive city, increasingly at risk from the effects of climate change and food insecurity, and increasingly at risk from mental illnesses and worsening mental health in part related to social isolation from the pandemic and new infectious diseases. 3

1 OLTCA ‘The Data’. n.d. 2024. https://www.oltca.com/about-long-term-care/ the-data/.

2 Alzheimer Society of Canada. ‘Navigating the Path Forward for Dementia in Canada: The Landmark Study Report #1’. Accessed 24 October 2024. https://alzheimer.ca/en/research/reports-dementia/navigating-path-forward-landmark-report-1.

3 City of Toronto. ‘Toronto’s Population Health Profile: Insight on the Health of Our City (2023)’, 13 February 2023. https://www.toronto.ca/city-govern-

As Torontonians age, there is a greater need for full time care of older people and those with dementia; smaller facilities that are closer to home can mitigate the spread of infectious diseases, keep people in their community, improve quality of care without increasing costs, and maintain their social support systems where family and friends can visit frequently and effortlessly. This is especially important as both voluntary and involuntary relocation of older people can be traumatic and lead to a loss of social support systems, and an increase of falls and premature deaths. However, rather than addressing the housing and healthcare crises together, facilities are being torn down like the 6-storey Cedarvale Terrace Long-Term Care Facility with 217 beds and 24/7 nursing care, being replaced by a 19-storey condo building with 87 residential units and no plan on where residents will go.4

Smaller facilities closer to home include those in urban environments that can be transit-oriented and have excellent walkable amenities and services, but can often be disconnected from nature and lack access to natural spaces, as well as adequate daylighting, fresh air, and intimate ‘backyard’ garden spaces. Mixed use, intergenerational housing developments with LTC facilities and green courtyards may be a solution to providing healthcare services and access to natural spaces to older persons in urban settings. This natural component is crucial for the health and wellbeing of all residents like in wandering gardens, and may be furthered through the integration of community permaculture farming practices. Horticultural therapy has proven an effective method for providing therapeutic benefits to older persons, and the integration of agricultural activities in long term care homes doubles as a biophilic benefit of interacting with nature and its associated physiological and psychological benefits, the fulfilling psychological and nourishing qualities of contributing to a community, feeling a sense of purpose, rewarding stimulation of overcoming challenges, and the health benefits of consuming fresh organic foods. Providing and preparing food for one’s family and community has deep evolutionary roots; in an multigenerational urban context, this can mean that farming and cooking can be healthy intergenerational activities that bring families together.

ment/data-research-maps/research-reports/public-health-significant-reports/ health-surveillance-and-epidemiology-reports/2022-population-health-profiles/.

4 ‘19-Storey Condo Proposed for Redevelopment of Long Term Care Home in Forest Hill | UrbanToronto’. n.d. https://urbantoronto.ca/news/2022/09/19storey-condo-proposed-redevelopment-long-term-care-home-foresthill.49336.

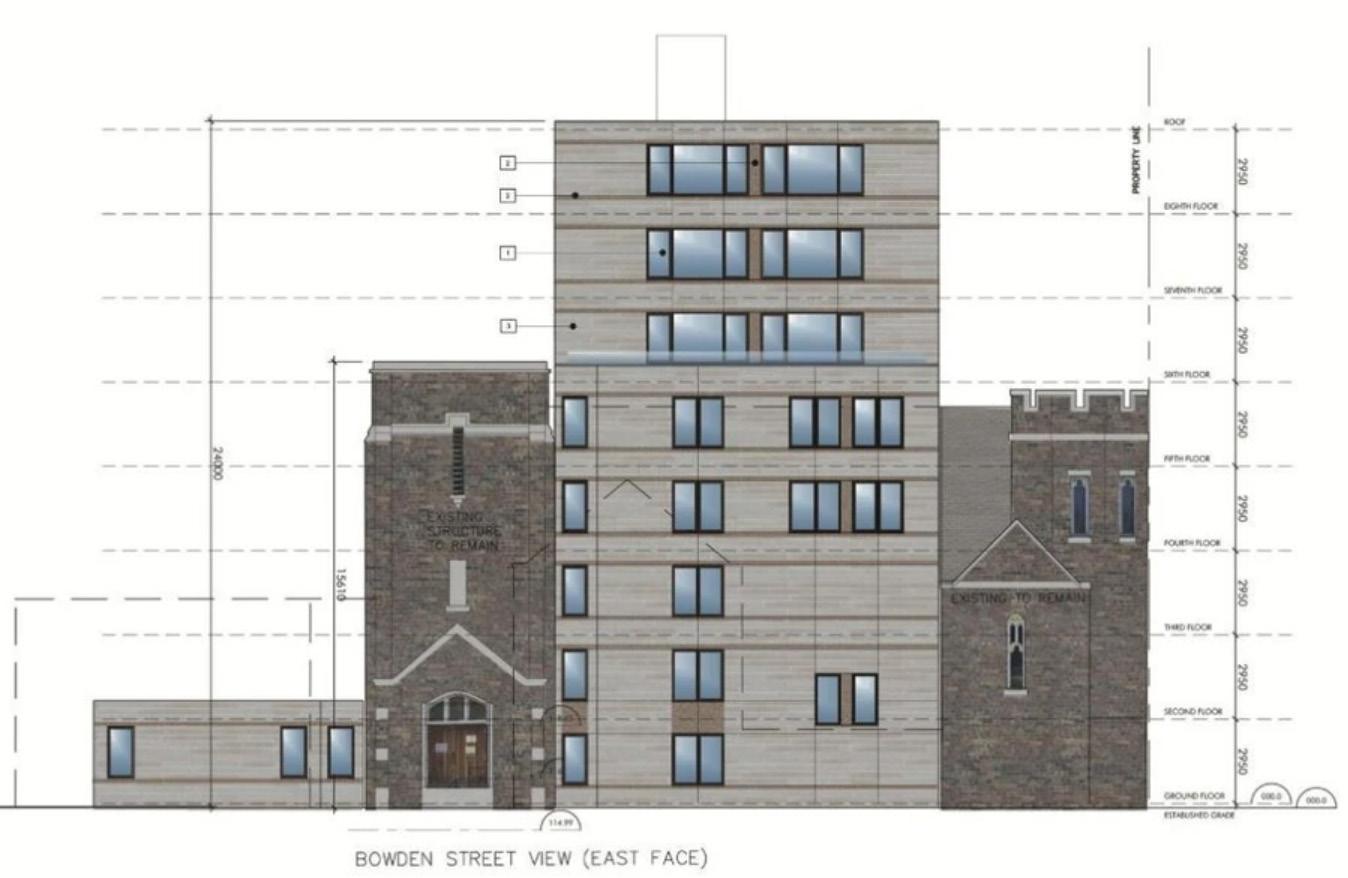

Toronto’s proposed plan to respond to the long term care crisis is to renovate and construct new facilities but it is difficult to find adequate land to build on and nearly half of all LTC facilities need to be redeveloped. Substantial renovations or additions typically require the involuntary relocation of residents to another home during construction, but a shortage of beds can make this process even more difficult. 1 There is a significantly increased complexity of renovating long-term care homes to meet current standards as sprinkler upgrades, asbestos removal, water pressure, and electrical capacity upgrades require major renovations from specialized contractors across trades that are facing labor shortages. The construction of new facilities is made exceptionally difficult if adequate land cannot be acquired for a site, which is increasingly difficult as the need for housing has exhausted nearly every adequate site in urban areas like in Toronto.2

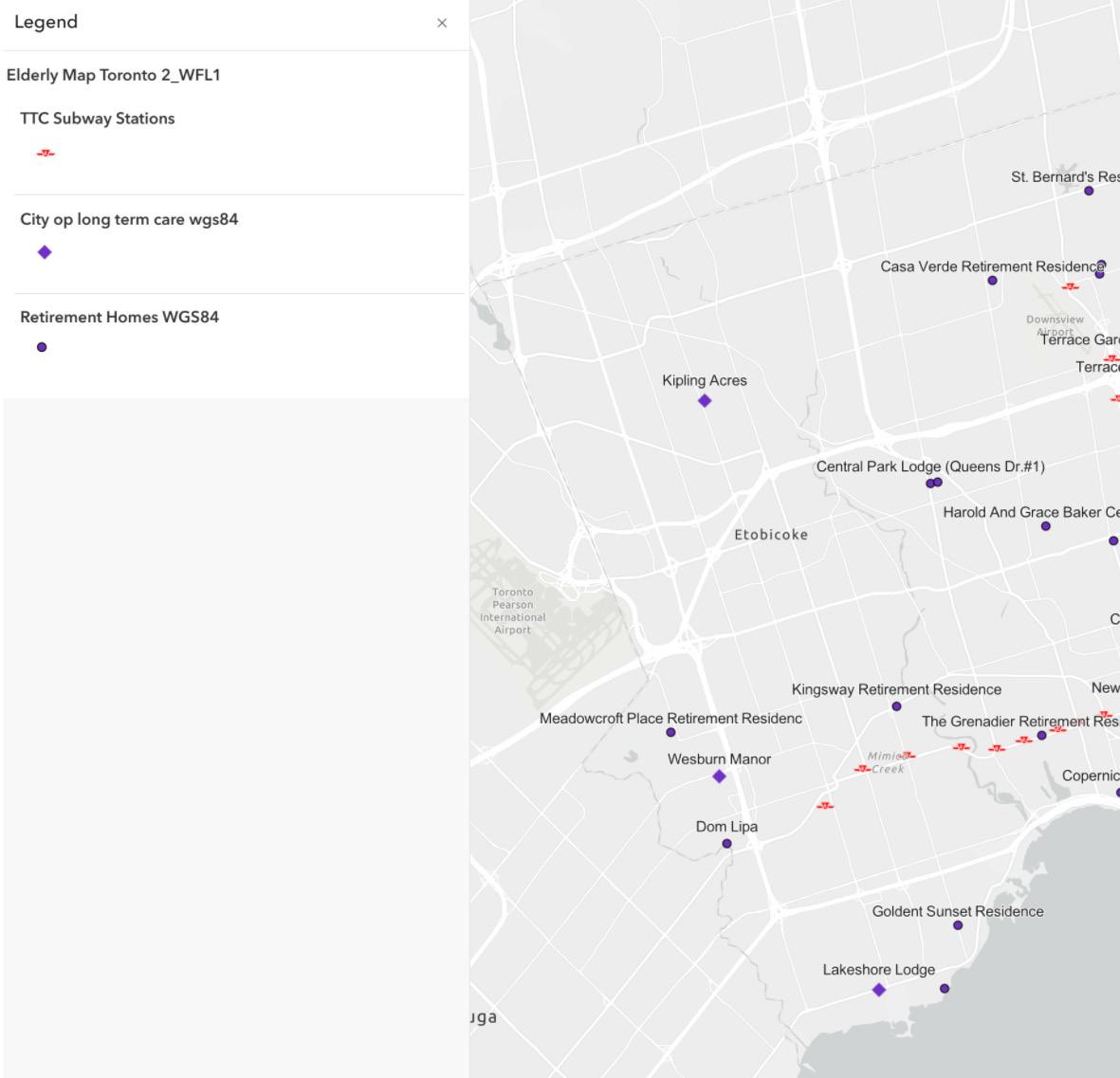

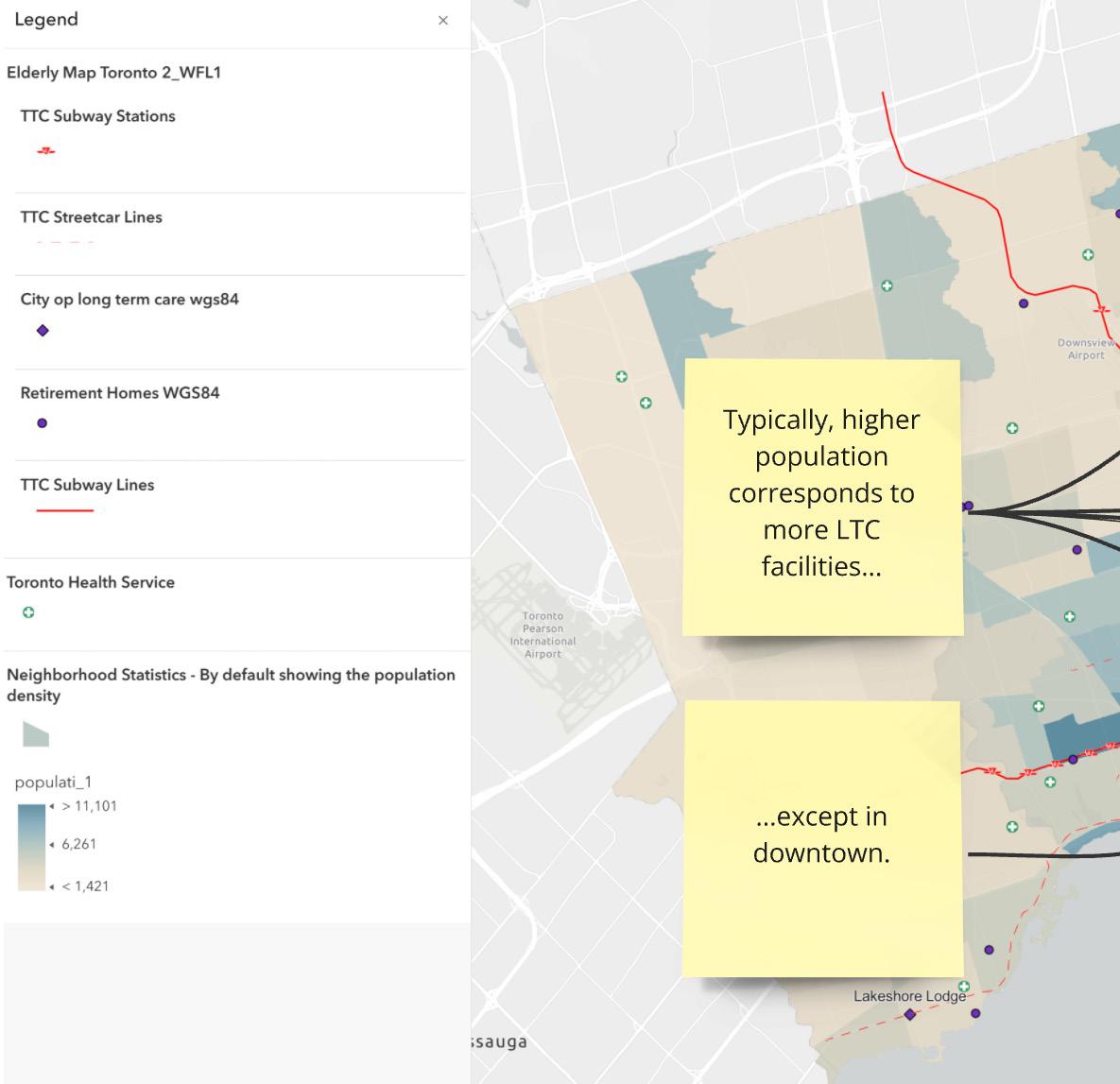

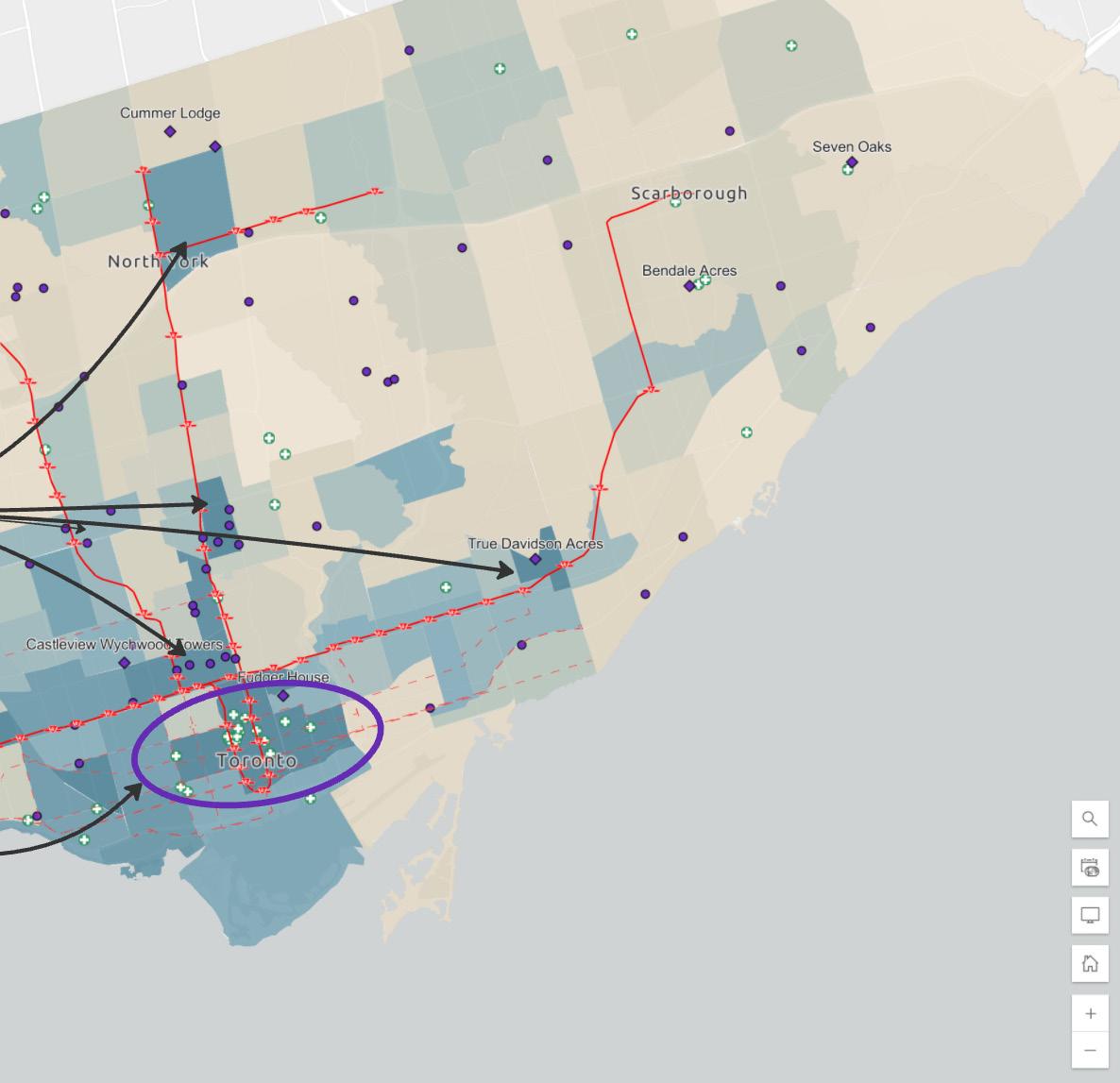

The ideal site for an urban long-term care facility is well-served by transit, green space, amenities, intergenerational opportunities, and neighborhood services, but such that the area is not already saturated with long-term care facilities. The demand for long-term care in Toronto is everywhere, but it is best if equally and proportionally distributed across the city as a function of population. It is important to reduce the distance from one’s community to the nearest long-term care facility to maintain one’s established connection to place, community, routine, and social support systems.

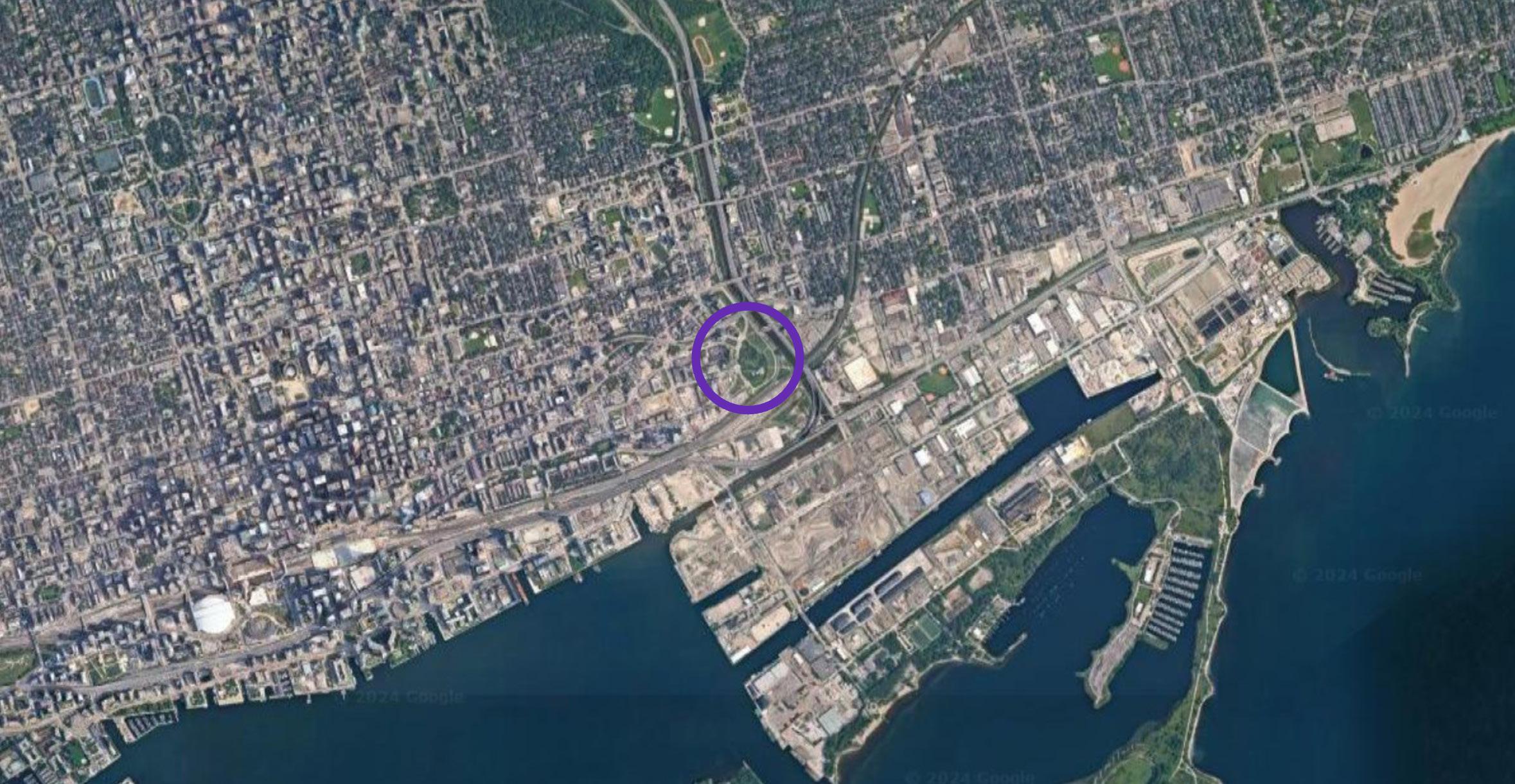

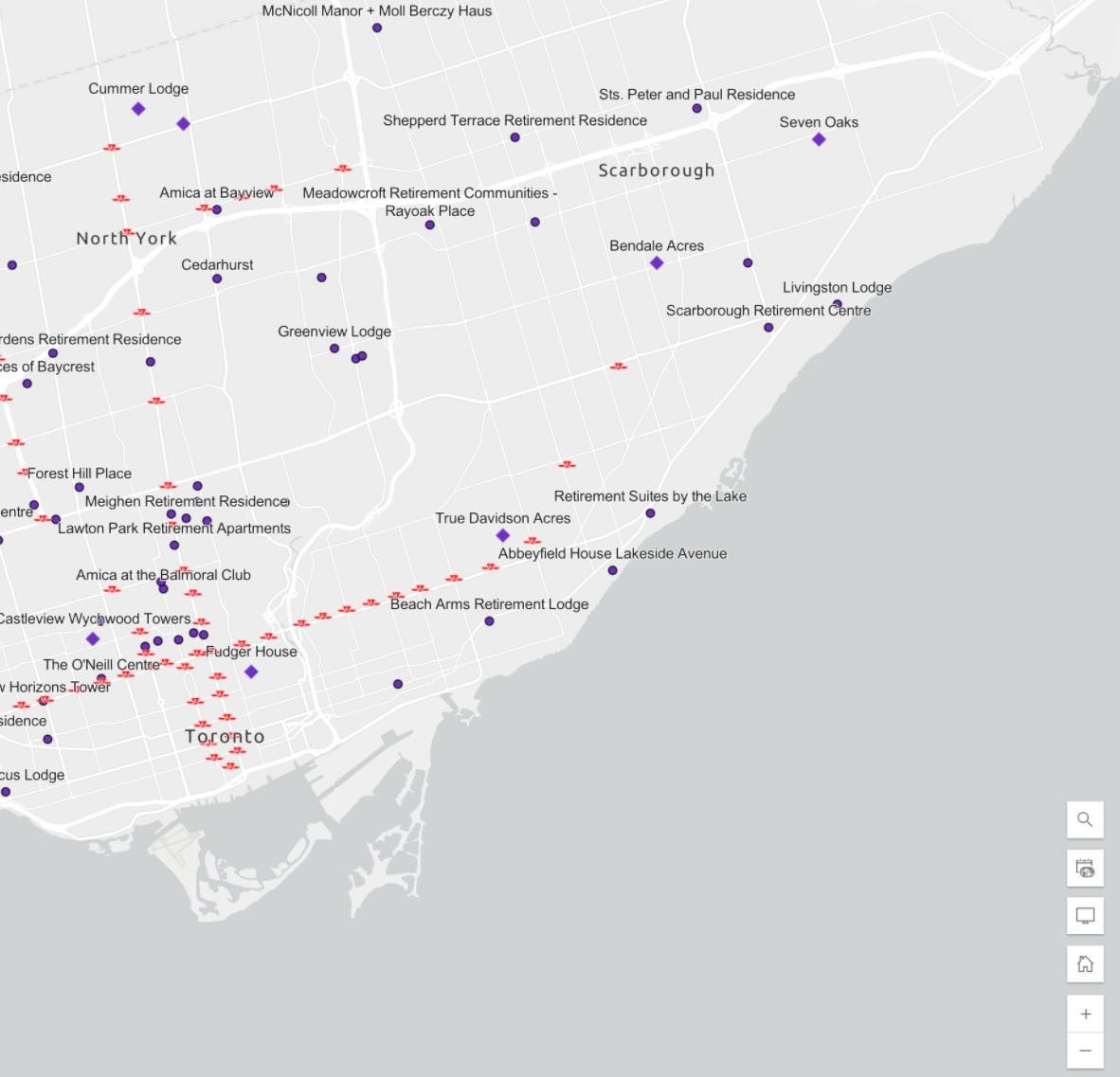

The process of selecting a site for this thesis prospectus involved a comprehensive mapping process of Toronto’s subway and streetcar infrastructure, population density, population density 65+, healthcare facilities, various amenities, and longterm care facilities. Several sites were found at the intersection of transit, amenities, and population density but in gaps found where there was an inadequate or complete lack of long-term care facilities.

The first site investigated was immediately south of the newly decommissioned Downsview Airport where Northcrest Developments is proposing a large housing development on the former airport runway and adjacent brownfield lands. This site was interesting as there will be a significant and con1 ‘Building and Redevelopment’. n.d. OLTCA. https://www.oltca.com/advocacy/building-redevelopment/. 2 Ibid.

stant influx of population, over 110,000 residents and 45,000 workers on the site that will be developed over the next 40 years. The site is transit-rich, amenity-rich, and walkable but after speaking to the Developers, I had found the only consideration was that there is currently a LTC facility on the site and no further facilities planned which meant there was a design opportunity to provide aging in place for the site’s future residents. However, there ultimately too many unknown factors with such a large project and timeline, and it was not selected.

The second site investigated was the parking lot of Warden Subway station with excellent access to nature, forested areas, walking paths, and a nearby hospital but there was already a large nearby non-profit long term care facility in the vicinity and plans to develop that parking lot with mid rise condos. The site was also insufficiently dense to warrant a high-rise building and so was rejected in the selection process.

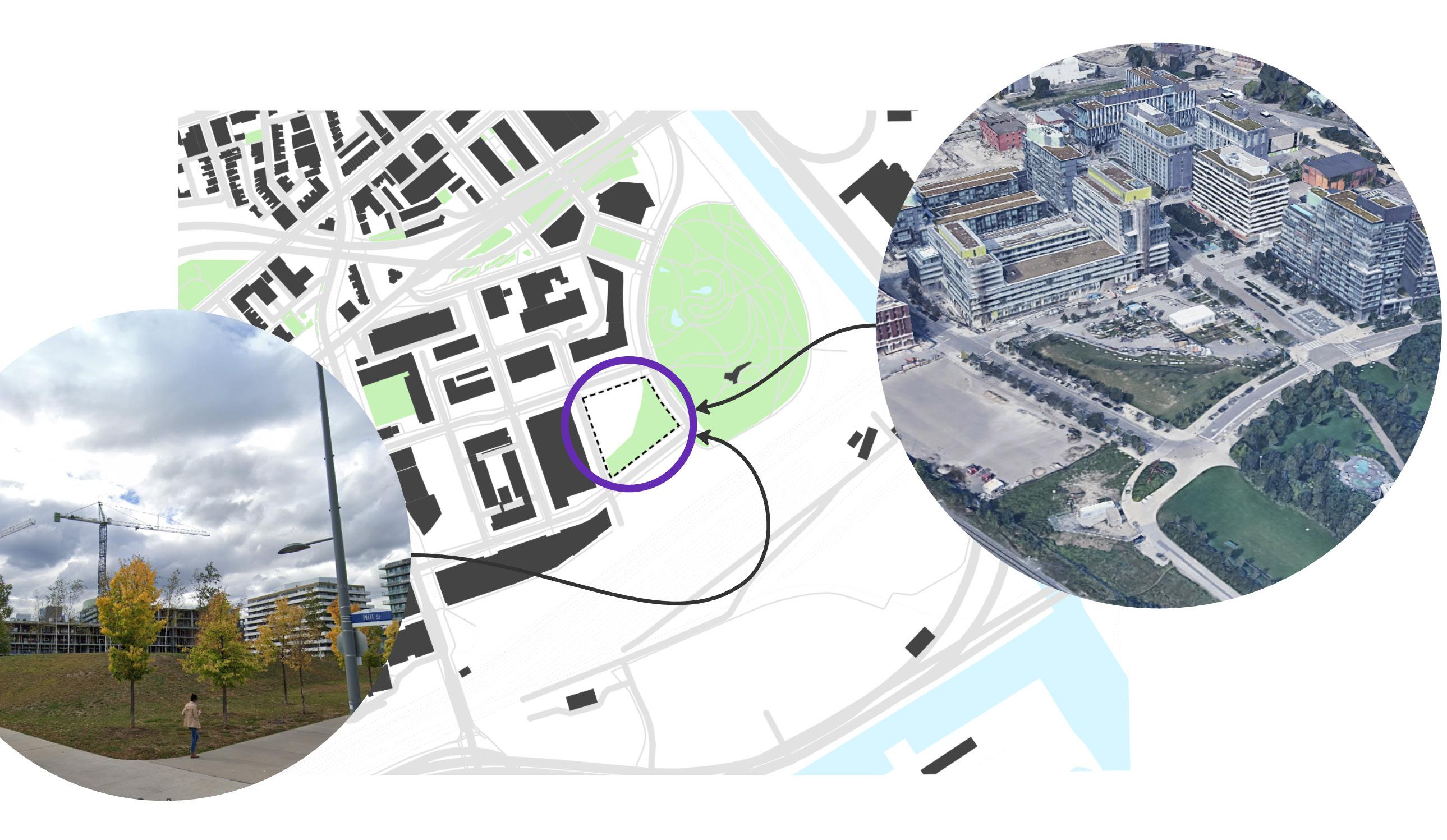

The site that was ultimately selected is 495 Front St E, a currently vacant site adjacent to Corktown Commons. The site has undergone significant redevelopment, transforming from former industrial lands into a mixed-use community designed around a significant park. This 7.3 hectare park sits atop Toronto’s Flood Protection Landform (FPL) that acts as a flood barrier and sponge to prevent flooding in Toronto’s Financial District and the West Don Lands.3 Along with the park, the site is adjacent to mid rise condo buildings and separated from the Don trainyard and railways by an empty site currently used for industrial storage. This site is at a key intersection of a lack of LTC facilities in Toronto’s concrete-dominated downtown and the vast open space of Corktown Commons, the Don River, and Lake Ontario. The site is rich in history and exists at a critical moment in the development of Toronto’s downtown where every possible lot is being used for the construction of placeless and apathetic glass condo buildings rather than the services Toronto desparately needs. This site represents a significant opportunity to provide multigenerational mixed use long term care in a dense, well-connected urban site while providing residents with salutogenic design and agrotherapy through a wealth of indoor and outdoor gardens and agricultural amenities.

3 Bonnell, Jennifer L. 2018. Reclaiming the Don : An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,. https:// doi.org/10.3138/9781442696808.

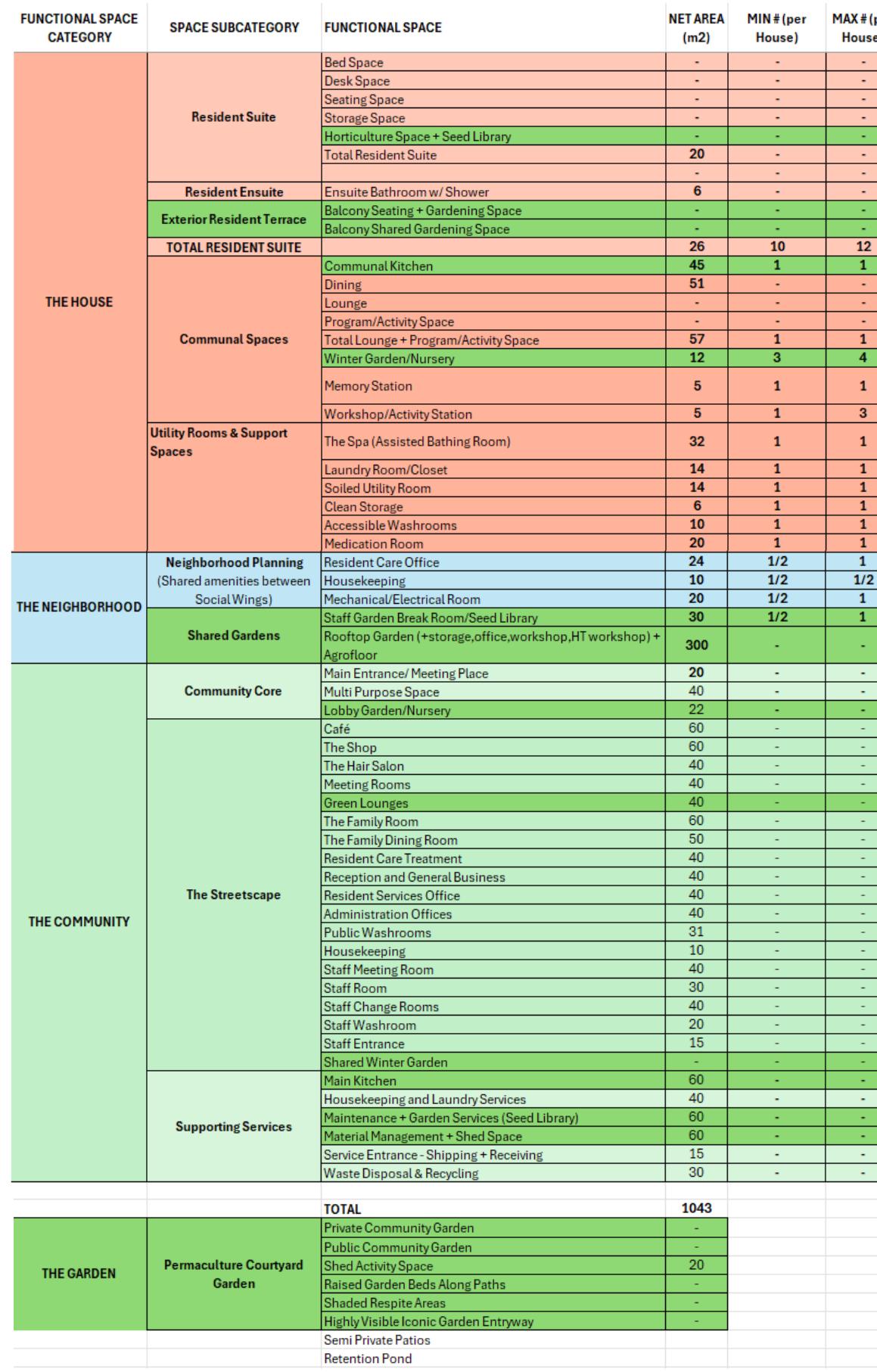

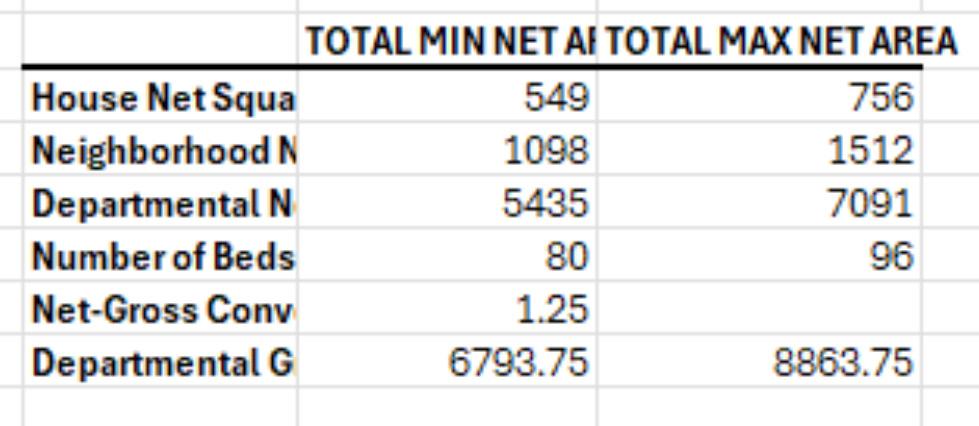

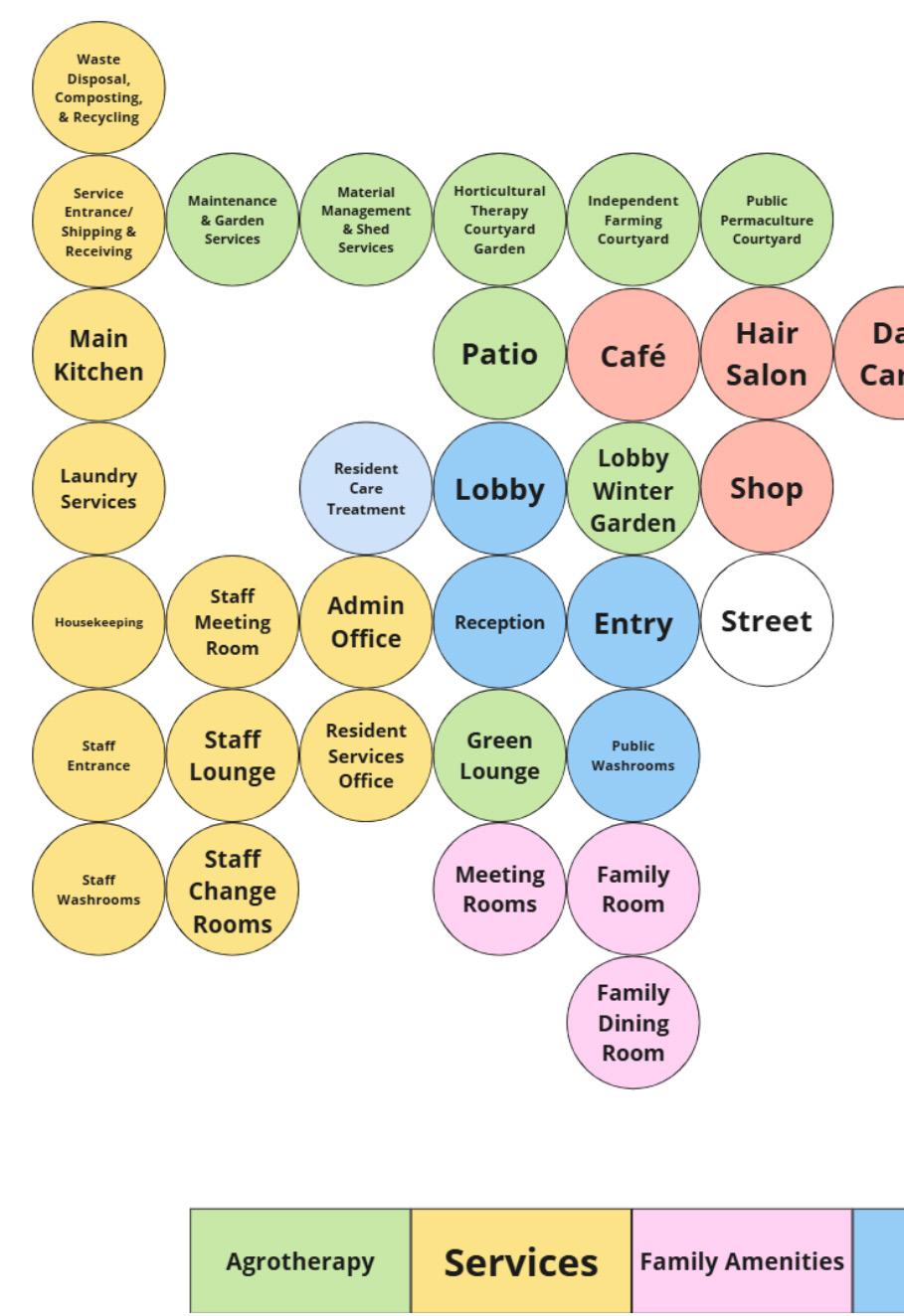

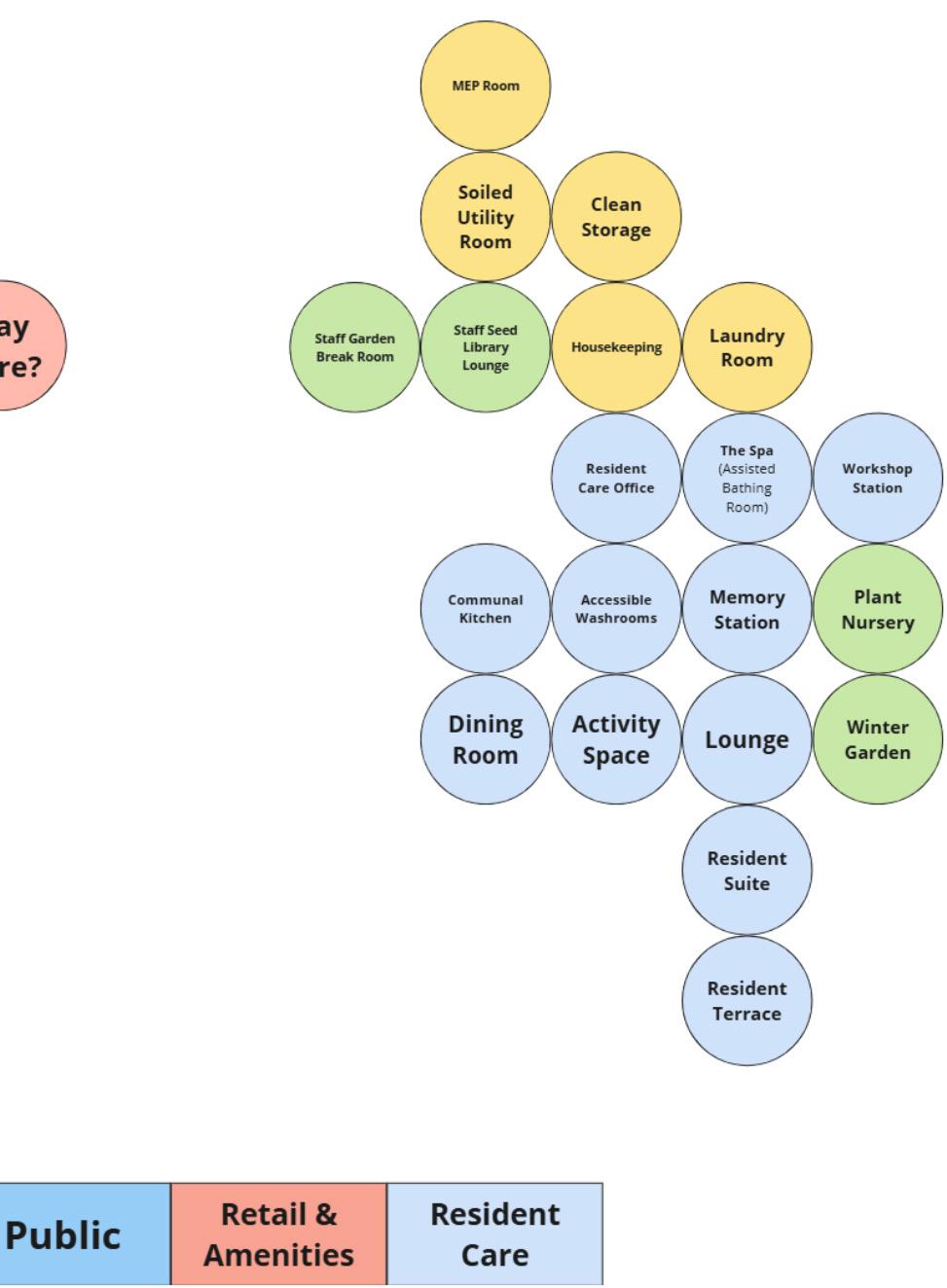

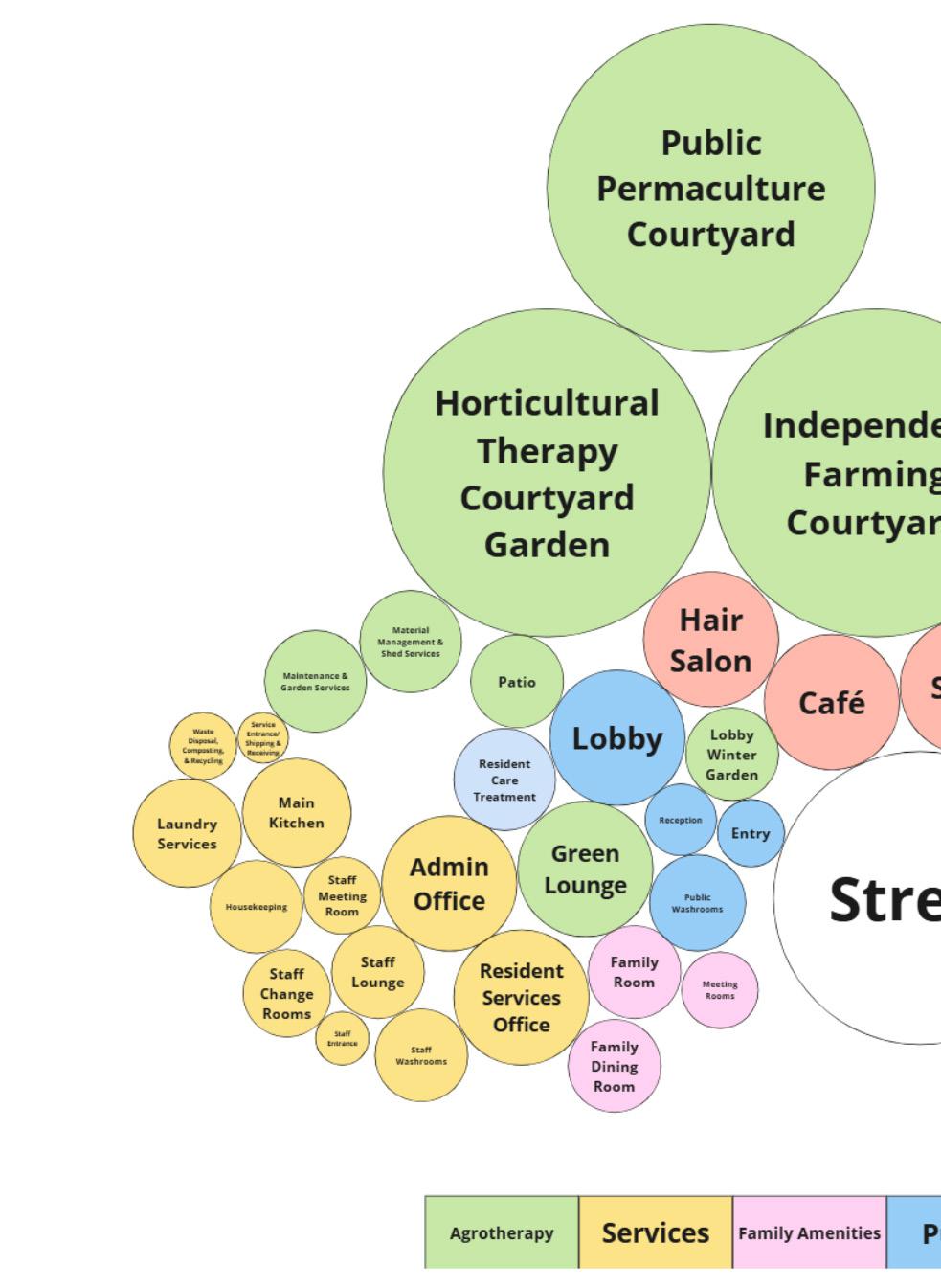

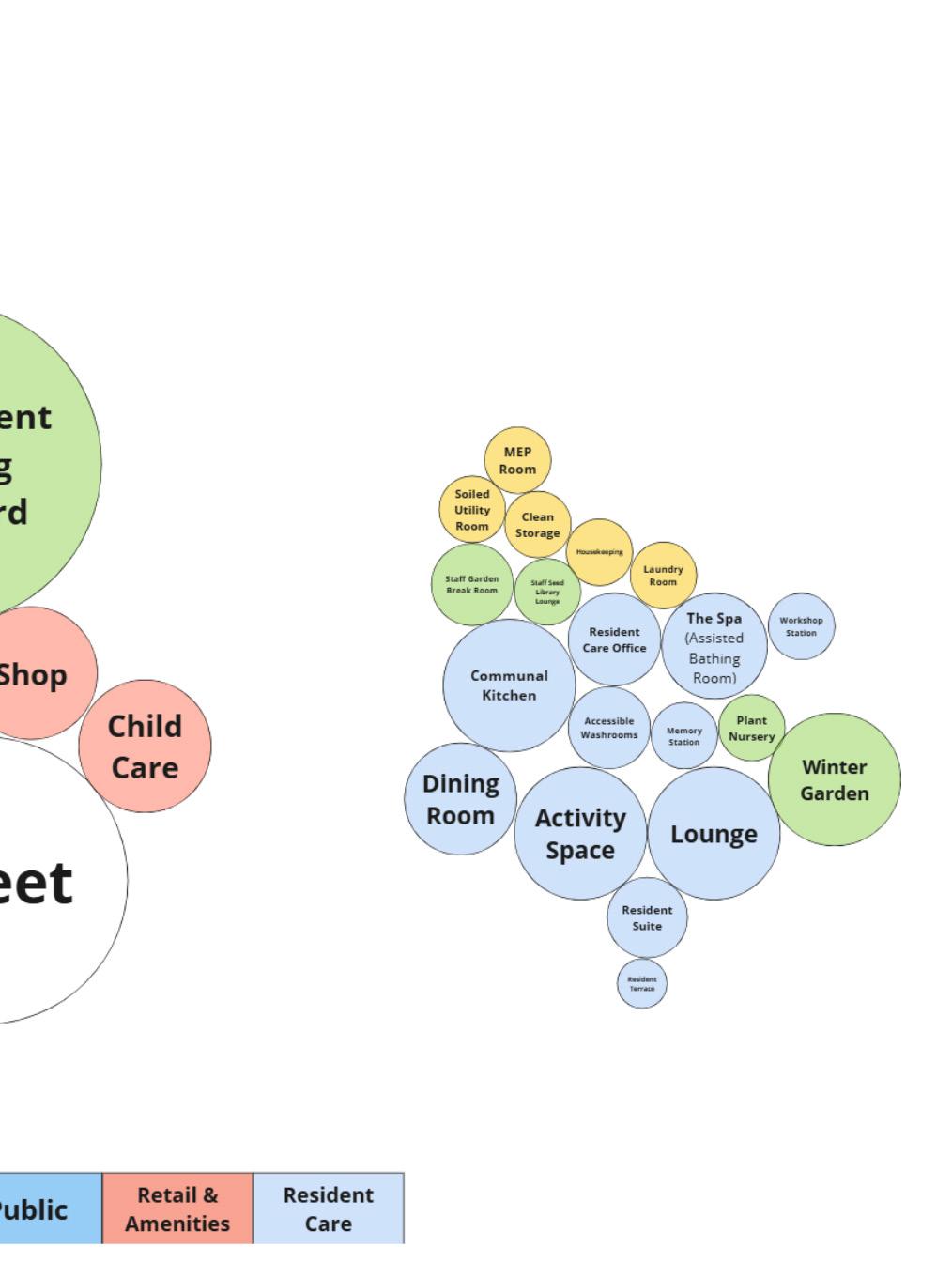

5.1 Appendix A: Functional Space Program

5.1 Appendix B: Functional Space Adjacencies

5.1 Appendix C: Functional Space

Adjacencies by Area

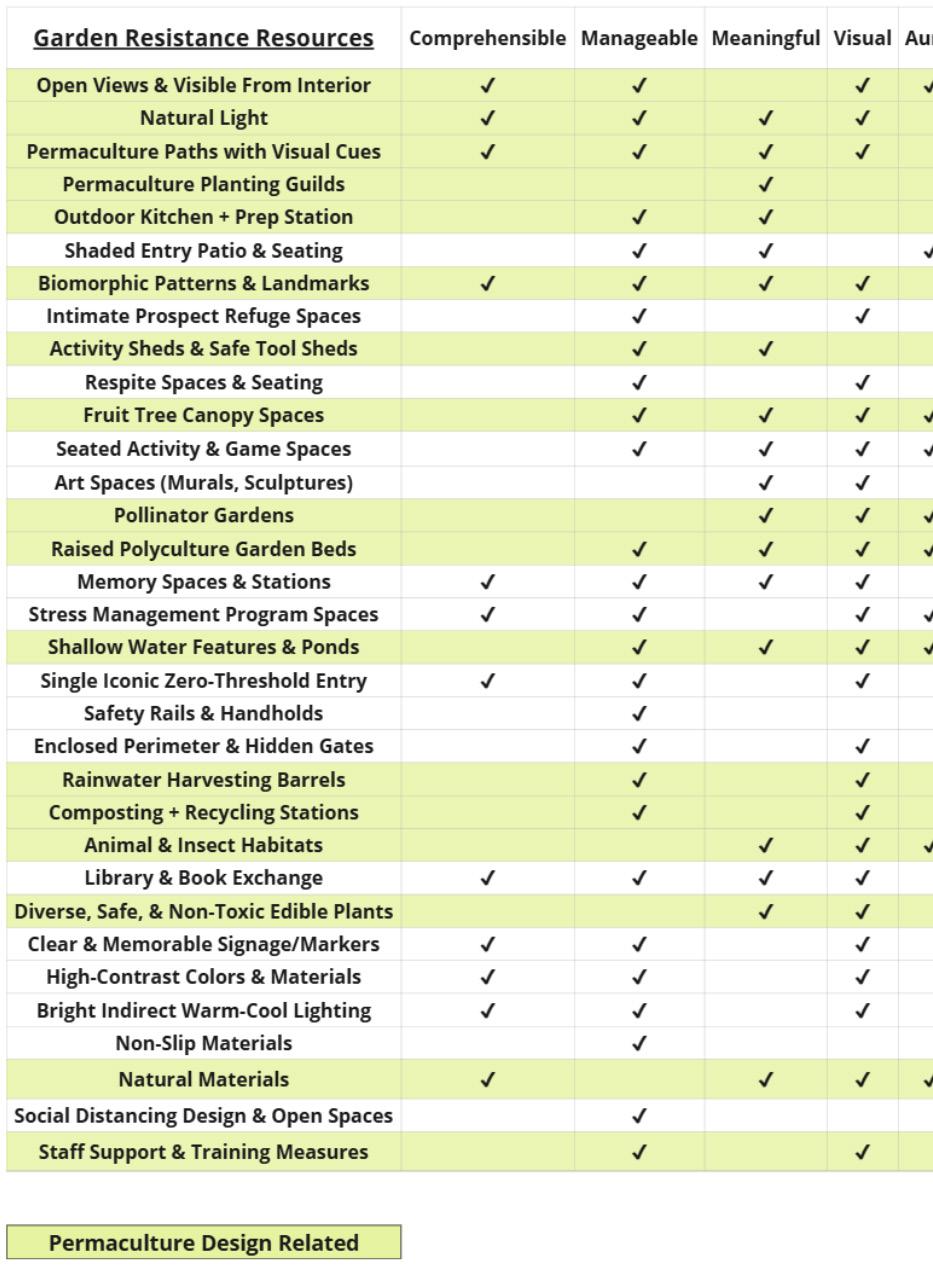

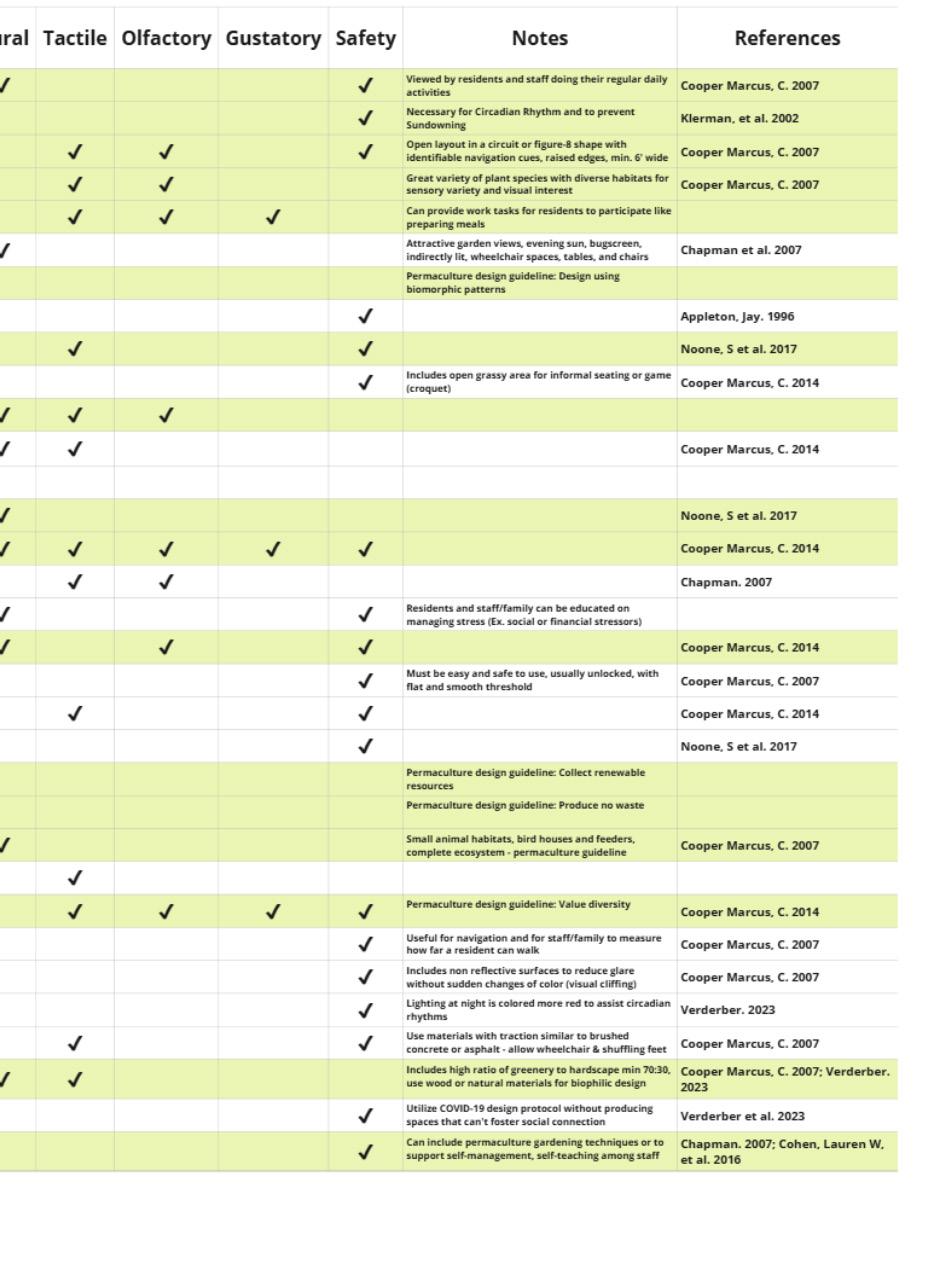

5.1 Appendix D: Garden Resistance

Resources - Effective Dementia

Garden Design Guidelines

5.2 Appendix E: Site AnalysisMapping Subway Stations, LTC, and Nursing Homes

5.2 Appendix F: Site AnalysisMapping Subway Stations, LTC, and Nursing Homes

Alexander, Christopher, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein. ‘A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction’. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (1977) introduces a system of design principles that guide the design of the built environment from the largest to smallest scales. At the core of this book as part of a greater trilogy of books, is the idea that people should design for themselves their own houses, streets, and communities. These design principles are then fundamentally human-centric which directly address the experiential qualities of spaces and places. This Pattern Language is a practical language organized with an image, an introductory paragraph, a headline in bold, an empirical background, a solution in bold, a diagram, and a concluding paragraph. The book is incredibly useful for design at any scale and describes for example, infrastructure to promote dancing in the street, appropriate community population sizes, the importance of site repair and maintaining green space, and appropriate window placement. This seminal text is critical to the design of multigenerational, prefab, salutogenic, mixed-use, high-rise Long Term Care as a guideline on appropriate and considerate design within a complex and novel design challenge. It is critically important when designing the new to not forget the timeless, tried and tested design solutions and guidelines as laid out in this nearly 50 year old book.

Appleton, Jay. 1996. ‘The Experience of Landscape’. Rev. ed. New York: Wiley.

Appleton’s seminal work in landscape aesthetics ‘The Experience of Landscape’ is critical for a deep understanding of the care of Seniors, especially those with Dementia. This is primarily due to Prospect-Refuge Theory that proposes evolutionary psychology is a critical element of design in which both residents and caregivers require prospects or clear views of the environment, and secure refuges in which one can feel safe and possibly be alone. The combination of these concepts is then prospect-refuge in which a resident or caregiver may maintain prospect while achieving refuge, this is especially important for caregivers to find a space to recharge wherein they may still possess a clear sightline of the residents to respond to an emergency. This is also important for residents to have a place of refuge but such that prospect can be a tool to minimize boredom and feelings of isolation if one can look out at others. Appleton’s concepts extend to symbolism in landscapes and how water, vegetation, or topography can signify safety or danger, and that these aesthetic preferences have developed as survival instincts as humans have evolved.

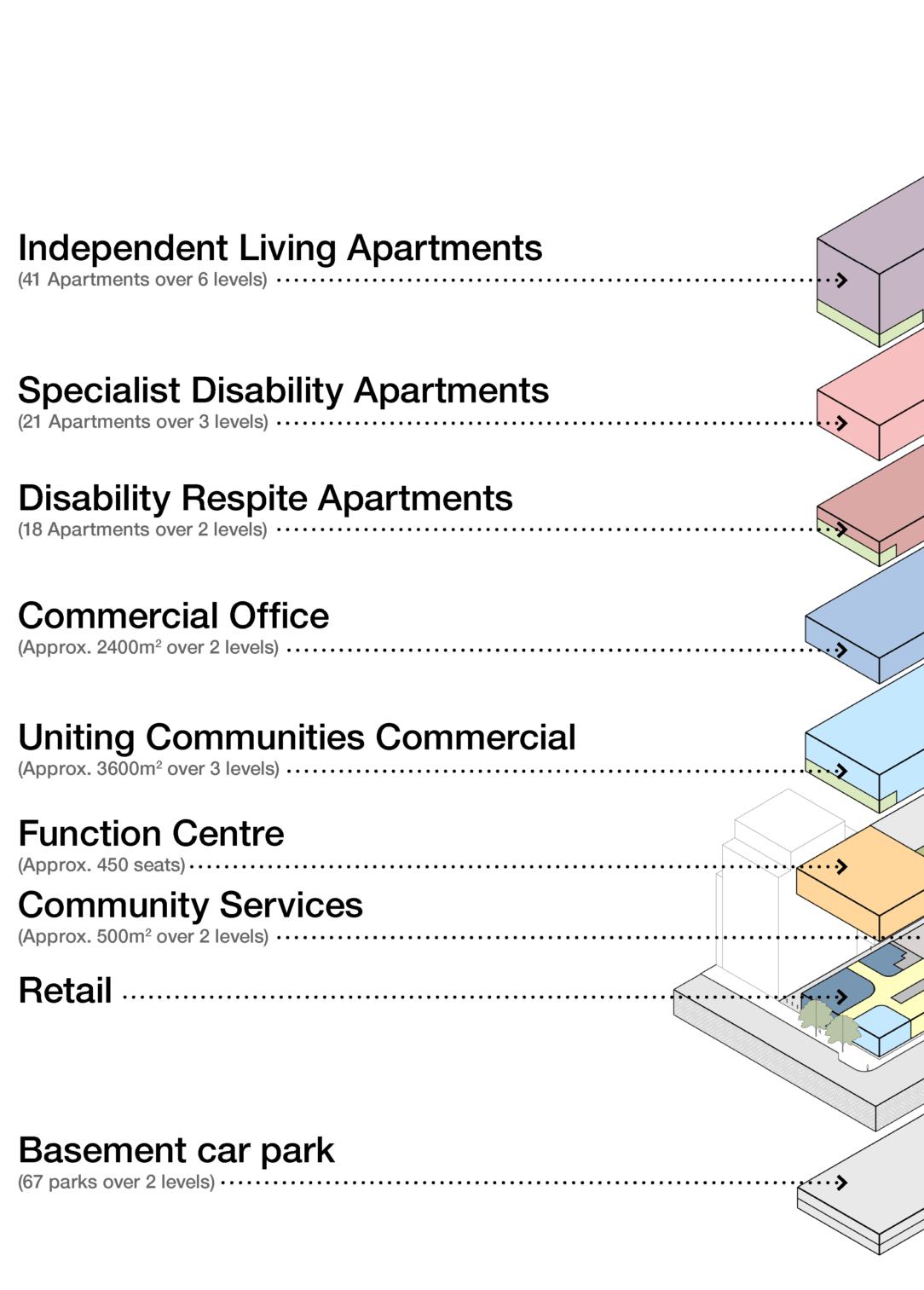

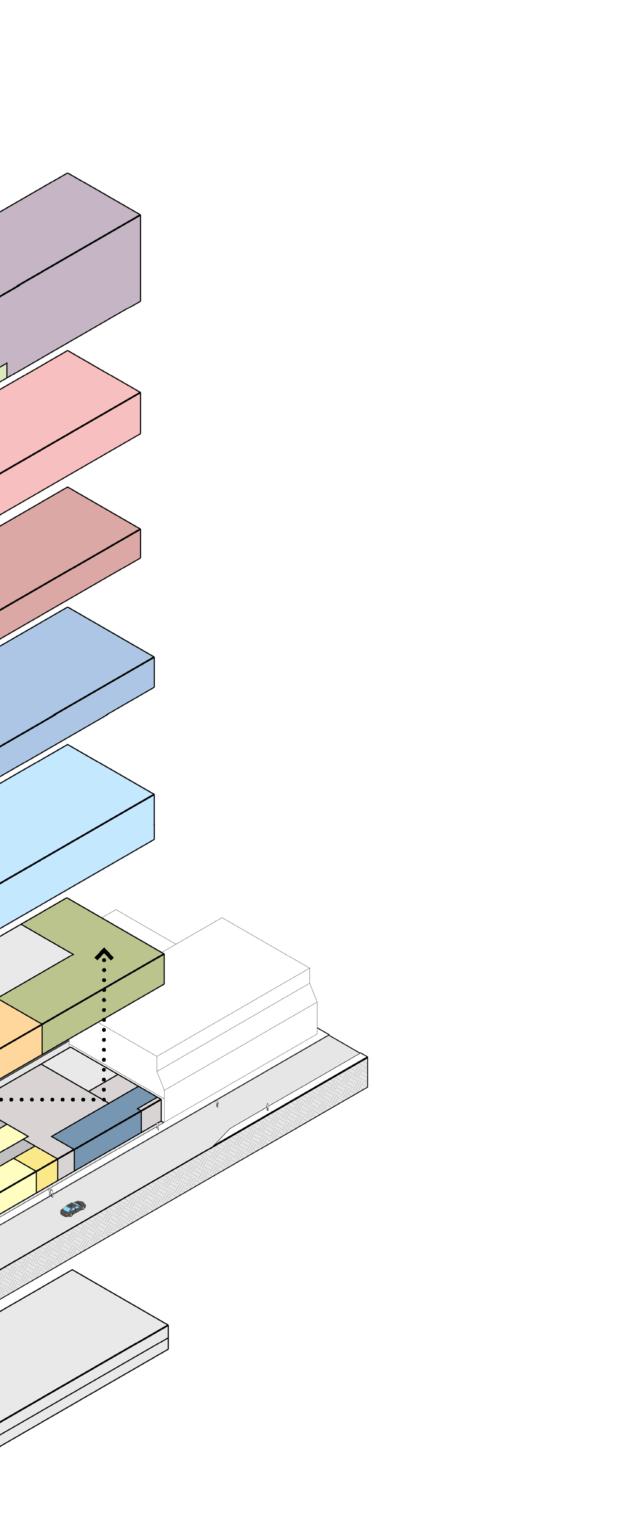

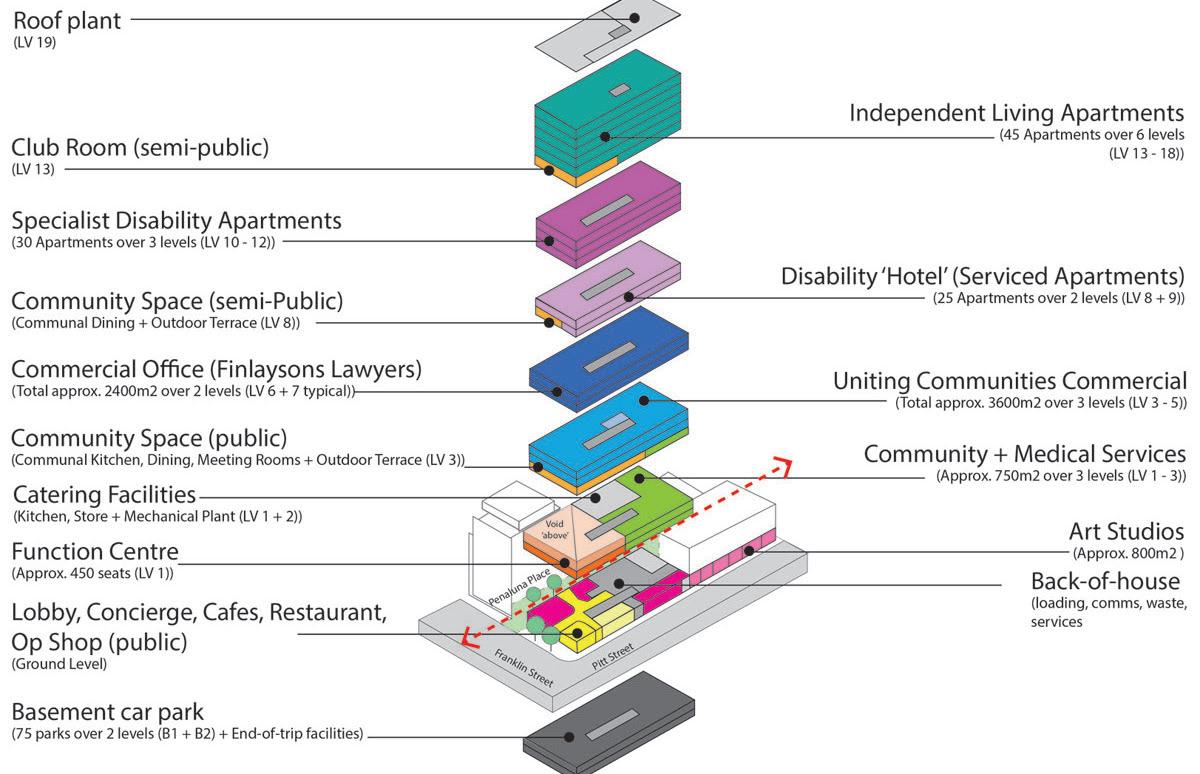

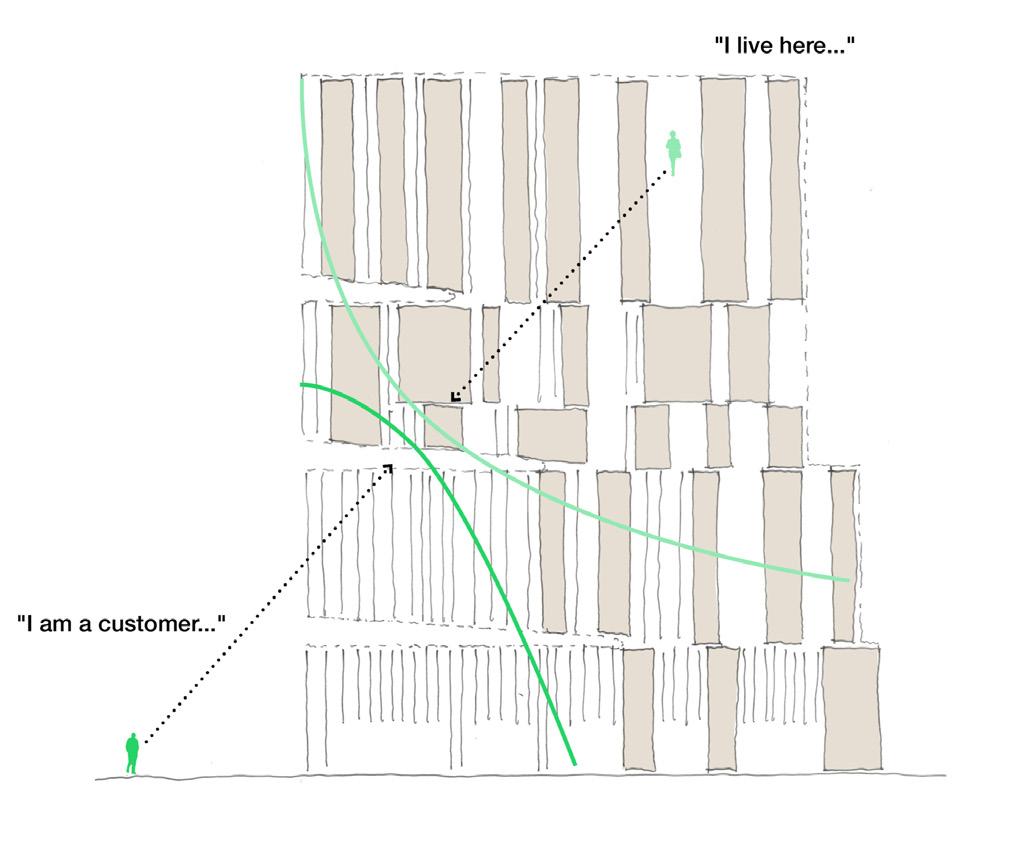

Barrie, Helen, Kelly McDougall, Katie Miller, and Debbie Faulkner. 2023. ‘The Social Value of Public Spaces in MixedUse High-Rise Buildings’. Buildings and Cities 4 (1): 669–89. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.339.

The study ‘The Social Value of Public Spaces in Mixed-Use High-Rise Buildings’ explored how shared spaces within U City Adelaide—a 20-storey mixed-use development in Adelaide, Australia foster social interaction and community engagement. The building was completed in 2019 by the non-profit Uniting Communities, U City integrates diverse uses, including retirement living, disability accommodation, services for vulnerable community groups, commercial tenants, cafe and retail outlets, and corporate conference facilities, making it an ideal setting for examining the social value of public spaces within buildings in urban environments. The study highlighted how U City’s public areas, such as the café lounge, communal kitchen and dining spaces, outdoor terraces, community meeting rooms, and multi-purpose club rooms, create opportunities for connection and interaction among residents and the broader public. By offering inclusive amenities like a second-hand store and integrated medical and community services, these spaces attract a diverse range of users, encouraging engagement and expression. This study is critically relevant to the research of multigenerational mixed-use high-rise long term care as it examines the social value of public amenity spaces within a high-rise long term care facility. Researchers concluded that these shared spaces act as catalysts for social cohesion, enhancing community-building through intentional design and programming, and in an urban environment with high land costs, the social value of shared spaces must be advocated for with evidence. These spaces are Generalized Resistance Resources that promote health and well-being and can keep the residents

and community members socially connected and healthy. Additionally, from an intergenerational perspective, the integration of long-term care facilities and public amenities supports aging in place while fostering relationships across generations. This research underscores the potential for mixed-use high-rises like U City to not only serve as functional spaces but also as vibrant community hubs that enhance urban life.

Dorrah, Dalia H., and Tamer E. El-Diraby. 2019. ‘Mass Timber in High-Rise Buildings: Modular Design and Construction; Permitting and Contracting Issues’. Modular and Offsite Construction (MOC) Summit Proceedings, May, 520–27. https://doi.org/10.29173/mocs134.

The paper ‘Mass Timber in High-Rise Buildings: Modular Design and Construction; Permitting and Contracting Issues’ by Dalia Dorrah and Tamer Diraby describe the inefficiencies in conventional construction especially in highrise buildings and explore the structural and fire safety benefits of mass timber as a structural material for use in Ontario. The paper indicates the novelty of mass timber in high-rise, the difficulties involved like permit approvals and contracting issues, and conducts interviews with industry professionals. The paper presents the lower climate change impact of timber of 34% to 84% compared to steel and concrete, the feasibility of transporting timber from Vancouver or Quebec as transportation costs represent a small percentage of costs, the ability to design once and reuse multiple times, benefits in prefabrication and installation, room for innovation, the need for investment in local supply chains and skilled labor, and the need for significant stakeholder engagement pre-design using the Integrated Project Delivery System. There are still complications and limitations to both modular construction and wood construction like fire, acoustic, structural, and financial costs but these can be addressed through creative physical and virtual design solutions like charring, encapsulation, the use of Building Information Modelling and Virtual Design and Construction to create scenarios for fire management and to maintain scheduling on a novel structural system that workers are not familiar with. Surprisingly, mass timber designed with a 2” layer for char can be fully exposed and an aesthetic material and is more fire resistant than steel that would otherwise need complete encapsulation or an expensive intumescent coating.

Marcus, Clare Cooper. 2007. ‘Alzheimer’s Garden Audit Tool’. Journal of Housing For the Elderly 21 (1–2): 179–191. doi:10.1300/J081v21n01_09.

Clare Cooper Marcus is a landscape architect and authority on healing landscapes and specifically, effective garden design for Seniors with varying types of dementia. In Alzheimer’s Garden Audit Tool, Marcus has supplemented her book Therapeutic Landscapes with effective Dementia Garden design principles in the book ‘Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces’, and Marcus goes into even further detail in ‘Alzheimer’s Garden Audit Tool’. This tool describes guidelines to effectively design an Alzheimer’s Garden to consider meaningfulness, comprehensibility of the environment, manageability of the environment, and safety considerations to manage risk. These design Guidelines range from specific design elements to general guidelines like the importance of a shaded entry patio or gazebo, rest spaces, open views, and plant diversity to add visual interest. Seniors with dementia are especially at risk of social isolation and loss of friends after a diagnosis, but the social and communal benefits of gardening can alleviate this burden. Appropriate garden design and easy access to exterior spaces through accessible thresholds are crucial for therapeutic benefits. This text is valuable in the design of multigenerational high rise long term care as there may be minimal site area for large Alzheimer Gardens at grade and thus design challenges emerge like rooftop or terrace gardens, or large winter gardens or agriculture-related programming that seeks to emulate the biophilic practices of gardening with minimal space.

Mittelmark, Maurice B., Georg F. Bauer, Lenneke Vaandrager, Jürgen M. Pelikan, Shifra Sagy, Monica Eriksson, Bengt Lindström, and Claudia Meier Magistretti, eds. 2022. ‘The Handbook of Salutogenesis’. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3.

The Handbook of Salutogenesis by Mittelmark et al. spans a vast number of topics on Salutogenesis but Chapters 34 and 17 were of specific focus to understand the underlying Salutogenic mechanisms and practical applications to keep people in a community and in a building healthy. The Handbook describes how Salutogenic design is a preventative approach to healthcare, where healthy environments keep people healthy. Salutogenic environments are, in part, created through active living where social participation and physical activity are encouraged and through a strong sense of coherence (SOC) where environments are structured, understandable, manageable, and meaningful.Salutogenic design employs resources (design elements and qualities) to invoke experiences related to SOC health outcomes such as comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness. The SOC-experiences are related to the quality of Salutogenic resources, and healthy inequity can be addressed by improving the quality of resources desired by health-deprived groups. Distribution of resources is crucial for salutogenesis, where opportunities for social activities, recreational activities, and physical activity must be made universally accessible through public transit and with adequate sidewalks to promote walking and its associated social and physical benefits. The perceived friendliness and pleasantness of a place encourage walking and socializing, but are significantly impacted by environmental impacts such as pollution. Access to green space is a significant contributor to healthy spaces, one study even found that “green space was the only urban variable directly connected to children’s perceived health”. Qualities of urban green spaces affect social groups differently, like the perception of safety, the amount of naturalized space, or programs such as community gardens - which have significant health benefits through physical activity, social connection, and healthier diet. Community gardening benefits include physical activity, social connection, biophilic affordances of being outdoors, healthful eating, more play self-efficacy, esteem, serene environments, silence, social initiatives in natural environments, sense of excitement, refreshment, relaxation, and solitude.

Payne, Sarah R., and Neil Bruce. 2019. ‘Exploring the Relationship between Urban Quiet Areas and Perceived Restorative Benefits’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (9): 1611. doi:10.3390/ ijerph16091611.

The study ‘Exploring the Relationship between Urban Quiet Areas and Perceived Restorative Benefits’ is crucial to this study as the site will be in an urban area that suffers from noise pollution. The benefits of quiet urban areas and their restorative benefits can drive crucial design goals around providing spaces that are silent as spaces of refuge. The study underscores the importance of urban quiet areas in promoting public health by providing environments conducive to psychological restoration. The researchers conducted a multi-site study across three UK cities, evaluating an urban garden, an urban park, and an urban square. They measured sound pressure levels and collected responses from 151 visitors regarding their perceptions of quietness, calmness, tranquility, and restorative benefits. The sample size was small but all three sites were associated with perceived health benefits, including feelings of relaxation and peace. Visitors reported that these areas provided restorative experiences, helping to alleviate stress and mental fatigue. The relationship between sound levels (both subjective and objective) and perceived restoration was not linear. Factors such as the types of sounds heard and other aspects of the environment influenced this relationship, suggesting that simply reducing noise levels may not be sufficient to enhance restorative experiences. It suggests that urban planners and policymakers should consider not only the reduction of environmental noise but also the preservation and enhancement of spaces that offer restorative experiences to urban residents. The importance of quiet through acoustic insulation and site consideration cannot be overstated in an urban site with residents suffering from Dementia as noises can trigger Dementia-related episodes that can manifest as anger or physical violence; acoustic design and quiet areas can provide refuge and restoration for residents easily susceptible to triggers from loud noises.

Verderber, Stephen, Umi Koyabashi, Catherine Dela Cruz, Aseel Sadat, and Diana C. Anderson. 2023. ‘Residential Environments for Older Persons: A Comprehensive Literature Review (2005–2022)’ . HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 16 (3): 291–337. doi:10.1177/19375867231152611.

Verderber et al. present a comprehensive literature review titled ‘Residential Environments for Older Persons’ offers an extensive analysis of research on residential settings for older adults and organizes findings into eight categories: community-based aging in place; residentialism; nature, landscape, and biophilia; dementia special care units; voluntary/involuntary relocation; infection control/COVID-19, safety/environmental stress; ecological and cost-effective best practices; and recent design trends and prognostications. The study showed that all-private room LTC units are safer, more private, and provide greater personal autonomy to residents. The study also indicated the importance of a home-like environment, the negative externalities of relocation, how family engagement in policy has increased, and how multigenerational living alternatives are increasing. These conclusions are significant to multigenerational high-rise long term care as aging in place in urban environments can promote multigenerational connection, maintain social connections, and mitigate the need for relocation in areas with the most people and greatest access to amenities and transit. Further, the design of home-like space sufficient LTC units demand privacy and prefabricated modular units may then offer the key to affordability while providing the amenities and safety needed by Seniors. The paper highlights the importance of on-site amenities as sources of satisfaction to residents and inversely how older persons who live independently and infrequently visit amenities like urban green spaces, parks, or cemeteries experienced the greatest risk of mortality as a function of their isolation and physical inactivity. The paper also indicates the therapeutic role of nature and landscape that is well-documented, how ecological sustainability has increased in priority, and infectious control measures are of high priority after COVID-19. This research underscores the need for effective garden design and salutogenic design to maximize the therapeutic benefits of nature and landscape for residents but also managing infection risk in communal settings. The necessity for Dementia special care units stated in this paper is valuable as a design strategy for modular construction as each unit should then be prefabricated as a dementia care unit which reduces design complexity and importantly can be used by any resident including those who may develop Dementia or are progressing through stages of Dementia. The literature review highlights the importance of safety, autonomy, family involvement, access to nature, sustainability, and infection control and underscores the necessity for ongoing research and innovation in the design of residential environments to accommodate the rapidly aging global population.

Wang, Kaiyue, Yaqi Li, Xiao Chen, Susan Veldheer, Chen Wang, Han Wang, Liang Sun, and Xiang Gao. 2024. ‘Gardening and Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Study and Mediation Analyses of 136,748 Adults Aged 45+ Years’. Nutrition Journal 23 (1): 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-024-00959-9.

In a Cross-sectional study of 136,748 adults analyzing Subjective Cognitive Decline in adults 45+, it was found that exercise, reduced depression, and higher consumption of fruits and vegetables contribute to a 28% reduction in self-reported Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) among gardeners. This study also emphasizes the multifaceted benefits of gardening, linking physical activity, mental health, and dietary improvements to cognitive health. This is a critical paper as it shows the universal benefits of gardening, exercise, and eating whole and fresh fruits and vegetables as salutogenic resources to improve well-being in general but specifically in the reduction of cognitive decline. With a growing population of Seniors, this highlights a critical element to healthy aging and reducing dementia among Seniors, thus improving quality of life and alleviating the need for increased levels of dementia care on an already strained healthcare system.

Abdelaal, Mohamed S., and Veronica Soebarto. 2019. ‘ Biophilia and Salutogenesis as Restorative Design Approaches in Healthcare Architecture’. Architectural Science Review 62 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1080/00038628.2019.1604313.

Abendroth, L. M., & Bell, B. (2018). ‘Public Interest Design Education Guidebook : Curricula, Strategies, and SEED Academic Case Studies’. 1st edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Alley, D., Liebig, P., Pynoos, J., Banerjee, T., & Choi, I.H. (2007). ‘ Creating elder-friendly communities: Preparations for an aging society’. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(1-2), 1-18.

Aung, M., Koyanagi, Y., Ueno, S., Tiraphat, S., & Yuasa, M. (2021) ‘A contemporary insight into an age-friendly environment contributing to the social network, active ageing and quality of life of community resident seniors in Japan’, Journal of Aging and Environment, (35)2, 145-160. (PDF). https://utoronto.sharepoint.com/:b:/s/daniels-public/EaZZtoX81ClMgr2I7jBMmd8BSVTbVL05RFtvS6-rxX0paQ?e=E3NHQL

Baldwin, C., Osborne, C., & Smith, P. (2013). ‘Planning for Age-Friendly Neighbourhoods’. J. Fetherstone, ed.;1–9. In International Society of City and Regional Planners (ISOCARP) Proceedings. https://research.usc.edu.au/discovery/ fulldisplay/alma99449075602621/61USC_INST:ResearchRepository.

Bonnell, Jennifer L. 2018. ‘Reclaiming the Don : An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley’ . Toronto: University of Toronto Press,. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442696808.

Briggs, Rebecca, Paul Graham Morris, and Karen Rees. 2023. ‘The Effectiveness of Group-Based Gardening Interventions for Improving Wellbeing and Reducing Symptoms of Mental Ill-Health in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Journal of Mental Health 32 (4): 787–804. doi:10.1080/09638237.2022.2118687.

Brunelli, Luca, Harry Smith, and Ryan Woolrych. ‘A Salutogenic Urban Design Framework: The Case of UK Local High Streets and Older People’. Health Promotion International 37, no. 5 (26 October 2022): daac102. https://doi. org/10.1093/heapro/daac102.

Bouricha, Donia Maalej, and Dorra Maalej Kammoun. ‘Upgrading the Living Space of the Elderly Person: Towards a Healthcare Design’. Journal of Salutogenic Architecture 2, no. 1 (26 December 2023): 85–103. https://doi.org/10.38027/ jsalutogenic_vol2no1_6.

Buffel, T., Phillipson, C., & Scharf, T. (2012). ‘Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities’. Critical Social Policy, 32(4), 597-617. (PDF). https://utoronto.sharepoint.com/:b:/s/daniels-public/Ebicylqwu5xMorO3XFyr1QgBtrpy8TsFtrOPpfq9lsaqog?e=NYjBzg

Campbell, N. (2015). ‘Designing for social needs to support aging in place within continuing care retirement communities’. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 30(4), 645-665. (PDF). https://utoronto.sharepoint. com/:b:/s/daniels-public/EXgZ53KSiThGn-Orft9ETmABTK-neGYNK8XAgzc78qU3BQ?e=N4WpLR

Cao, W., & Dewancker, B. (2021). ‘Interpreting spatial layouts of nursing homes based on partitioning theory’. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 1–18. (PDF).https://utoronto.sharepoint.com/:b:/s/daniels-public/ ESN9wdomxWRFtvurx0XoCRQByuCfof_i4KuCRZhOMLOMLA?e=ahRZhl

Chapman, Nancy J., Teresia Hazen, and Eunice Noell-Waggoner. 2007. ‘Gardens for People with Dementia: Increasing Access to the Natural Environment for Residents with Alzheimer’s’ . Journal of Housing For the Elderly 21 (3–4): 249–263. doi:10.1300/J081v21n03_13.

Chen, Zhanglei, Kar Kheng Gan, Tiejun Zhou, Qingfeng Du, and Mingying Zeng. 2022. ‘Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Pathways Between Environmental Characteristics and Perceived Restorativeness on Public Rooftop Gardens in China’. Frontiers in Public Health 10 (February): 801453. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.801453.

Clancy, Joe, and Catie Ryan. ‘The Role of Biophilic Design in Landscape Architecture for Health and Well-Being’ Landscape Architecture Frontiers 3, no. 1 (17 April 2015): 54–61. https://journal.hep.com.cn/laf/EN/Y2015/V3/I1/54.

Cohen, Lauren W., Sheryl Zimmerman, David Reed, Patrick Brown, Barbara J. Bowers, Kimberly Nolet, Sandra Hudak, Susan Horn, and the THRIVE Research Collaborative. 2016. ‘The Green House Model of Nursing Home Care in Design and Implementation’. Health Services Research 51 (S1): 352–377. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12418.

Courtney, Robert. 2015. ‘Harms and Benefits Associated with Exercise Therapy for CFS/ME’ . Disability and Rehabilitation 37 (5): 465–465. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.952453.

Dushkova, Diana, and Maria Ignatieva. 2020. ‘New Trends in Urban Environmental Health Research: From Geography of Diseases to Therapeutic Landscapes and Healing Gardens’. GEOGRAPHY, ENVIRONMENT, SUSTAINABILITY 13 (1): 159–171. doi:10.24057/2071-9388-2019-99.

Ericson, Helena, Mikael Quennerstedt, and Susanna Geidne. 2021. ‘Physical Activity as a Health Resource: A Cross-Sectional Survey Applying a Salutogenic Approach to What Older Adults Consider Meaningful in Organised Physical Activity Initiatives’. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 9 (1): 858–874. doi:10.1080/21642850. 2021.1986400.

Forsyth, A., Molinsky, J., & Kan, H. (2019). ‘Improving housing and neighborhoods for the vulnerable: Older people, small households, urban design, and planning.’ Urban Design International, 24(3), 171–186. (PDF). https://utoronto. sharepoint.com/:b:/s/daniels-public/Ec4_rKzger1EqbikihiPXjEBfSkMgZM4ZI6GQSxymZZIxw?e=N6Fl4e

Hancock, Trevor. “The Evolution, Impact and Significance of the Health Cities/Healthy Communities Movement.” Journal of Public Health Policy 14, no. 1 (1993): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342823.

Hämäläinen, Timo J., and Juliet Michaelson, eds. 2014. ‘Well-Being and beyond: Broadening the Public and Policy Discourse’. New Horizons in Management. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Howarth, Michelle, Alistair Griffiths, Anna Da Silva, and Richard Green. 2020. ‘Social Prescribing: A “Natural” Community-Based Solution’. British Journal of Community Nursing 25 (6): 294–298. doi:10.12968/bjcn.2020.25.6.294.

Lezwijn, Jeanette, Lenneke Vaandrager, Jenneken Naaldenberg, Annemarie Wagemakers, Maria Koelen, and Cees Van Woerkum. 2011. ‘Healthy Ageing in a Salutogenic Way: Building the HP 2.0 Framework’. Health & Social Care in the Community 19 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00947.x.

Marcus, Clare Cooper, Naomi A. Sachs, and Roger S. Ulrich. 2014. ‘ Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces.’ Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Morgan, Antony, Erio Ziglio, and Maggie Davies, eds. 2010. ‘Health Assets in a Global Context’. New York: Springer.

Negro, Sorell E., and Jean Terranova. “The Birds and the Bees: Recent Developments in Urban Agriculture.” The Urban Lawyer 47, no. 3 (2015): 445–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26423771.

NOGEIRE-MCRAE, THERESA, ELIZABETH P. RYAN, BECCA B.R. JABLONSKI, MICHAEL CAROLAN, H. S. ARATHI, CYNTHIA S. BROWN, HAIRIK HONARCHIAN SAKI, STARIN MCKEEN, ERIN LAPANSKY, and MEAGAN E. SCHIPANSKI. “The Role of Urban Agriculture in a Secure, Healthy, and Sustainable Food System.” BioScience 68, no. 10 (2018): 748–59. https://www. jstor.org/stable/90025670.

Nollman, Jim. 1994. ‘Why We Garden : Cultivating a Sense of Place’. 1st ed. New York: Holt.

Noone, S., Innes, A., Kelly, F., & Mayers, A. (2017). ‘‘The nourishing soil of the soul’: The role of horticultural therapy in promoting well-being in community-dwelling people with dementia’. Dementia (London, England), 16(7), 897–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215623889.

OLTCA ‘The Data’. n.d. 2024. https://www.oltca.com/about-long-term-care/the-data/.

Poppius, Esko, Leena Tenkanen, Raija Kalimo, and Pertti Heinsalmi. 1999. ‘The Sense of Coherence, Occupation and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in the Helsinki Heart Study’. Social Science & Medicine 49 (1): 109–120. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00105-7.

Pollans, Margot, and Michael Roberts. “Setting the Table for Urban Agriculture.” The Urban Lawyer 46, no. 2 (2014): 199–225. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24392804.

Rappe, Erja. 2005. ‘The Influence of a Green Environment and Horticultural Activities on the Subjective Well-Being of the Elderly Living in Long-Term Care’. Publications / University of Helsinki, Department of Applied Biology, 24. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Seah, Betsy, Geir Arild Espnes, Wee Tin Hong, and Wenru Wang. 2022. ‘Salutogenic Healthy Ageing Programme Embracement (SHAPE)- an Upstream Health Resource Intervention for Older Adults Living Alone and with Their Spouses Only: Complex Intervention Development and Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial’ . BMC Geriatrics 22 (1): 932. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03605-3.

Souter-Brown, Gayle, Erica Hinckson, and Scott Duncan. 2021. ‘Effects of a Sensory Garden on Workplace Wellbeing: A Randomised Control Trial’. Landscape and Urban Planning 207 (March): 103997. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103997.

Stoltz, Jonathan, and Christina Schaffer. 2018. ‘Salutogenic Affordances and Sustainability: Multiple Benefits With Edible Forest Gardens in Urban Green Spaces’. Frontiers in Psychology 9 (December): 2344. doi:10.3389/ fpsyg.2018.02344.

Sulander, T., Karvinen, E., & Holopainen, M. (2016). ‘Urban green space visits and mortality among older adults’ Epidemiology, 27(5), e34-e35. *https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27327021/

Thomaier, Susanne, Kathrin Specht, Dietrich Henckel, Axel Dierich, Rosemarie Siebert, Ulf B. Freisinger, and Magdalena Sawicka. “Farming in and on Urban Buildings: Present Practice and Specific Novelties of Zero-Acreage Farming (ZFarming).” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 30, no. 1 (2015): 43–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26341778.

Turki, Wouroud, Amal Bouaziz, Amine Hadj Taieb, and Chema Gargouri. ‘Guidelines for Greening Healthcare Spaces’. Journal of Salutogenic Architecture 2, no. 1 (26 December 2023): 113–24. https://doi.org/10.38027/jsalutogenic_vol2no1_8.

Vaandrager, Lenneke, and Lynne Kennedy. ‘The Application of Salutogenesis in Communities and Neighborhoods’. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, edited by Maurice B. Mittelmark, Shifra Sagy, Monica Eriksson, Georg F. Bauer, Jürgen M. Pelikan, Bengt Lindström, and Geir Arild Espnes. Cham (CH): Springer, 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK435839/.

Van Den Bosch, Matilda, Per-Olof Östergren, Patrik Grahn, Erik Skärbäck, and Peter Währborg. 2015. ‘Moving to Serene Nature May Prevent Poor Mental Health—Results from a Swedish Longitudinal Cohort Study’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12 (7): 7974–7989. doi:10.3390/ijerph120707974.

Yap, Xin Yi, Wai San Wilson Tam, Yue Qian Tan, Yanhong Dong, Le Xuan Loh, Poh Choo Tan, Peiying Gan, Di Zhang, and Xi Vivien Wu. 2024. ‘Path Analysis of Self-Care amongst Community-Dwelling Pre-Ageing and Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: A Salutogenic Model’. Geriatric Nursing 59 (September): 516–525. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.07.034.

Articles and Blogs:

Certomà, Chiara. “Critical Urban Gardening.” RCC Perspectives, no. 1 (2015): 13–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26241301.

Element5, ‘Mass Timber Resources (Brochures, Product Sheets, Case Studies)’, 25 February 2021. https://elementfive.co/resources/.

Mass Timber Housing. ‘Modular Approach — Mass Timber Housing’. https://masstimberhousing.com/modular-approach.

Board, Think Wood c/o Softwood Lumber. ‘Mass Timber Design Manual’. https://info.thinkwood.com/download/2022-mass-timber-design-manual.

Mazzucco, Lucy. ‘The Future of Long-Term Care: Integrating Age-Friendly Living into Urban Communities’ . Canadian Architect (blog), 6 June 2024. https://www.canadianarchitect.com/the-future-of-long-term-care-integrating-agefriendly-living-into-urban-communities/.

Wahl, Daniel Christian. ‘Salutogenic Cities & Bioregional Regeneration (Part I of II)’. Age of Awareness (blog), 8 April 2020. https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/salutogenic-cities-bioregional-regeneration-part-i-of-ii-2772a13bad9a.

Wellness design consultants. ‘Role of Salutogenic Design, Evidence Based Design & the Anthropocene in Healthy Building’. Accessed 18 September 2024. https://biofilico.com/news/salutogenesis-evidence-based-design-anthropocene-healthy-buildings.