Find some of Canada’s finest authors, photographers and artists featured in every issue.

is to promote Canadian culture by bringing world-wide readers some of the best Canadian literature, art and photography.

Devour: Art and Lit Canada

ISSN 2561-1321

Issue 020

Winter 2024 / 25

5 Greystone Walk Drive Unit 408

Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M1K 5J5

DevourArtAndLitCanada@gmail.com

Poetry Editor – Bruce Kauffman

Review Editor – Shane Joseph

Photography Curator – Mike Gaudaur

Front and Back Cover Feature Photographer – Nick White

Editor-in-Chief – Richard M. Grove

Layout and Design – Richard M. Grove

Dear Readers:

Welcome to this 20th issue of Devour: Art & Lit Canada. As usual we are bringing you some of Canada’s most talented writers, poets and photographers.

We hope you will tell your international readers about this all Canadian Magazine.

As always, thank you to our ongoing faithful section editors. In no special order, thanks to Bruce Kauffman, Shane Joseph and Mike Gaudaur. Thankyou to all of the contributors that make Devour a success.

We hope you will tell your international readers about this all Canadian Magazine.

See you between the pages.

Richard M. Grove otherwise know to friends as Tai

– Canada Coast to Coast to Coast – Photography Curator –Mike Gaudaur – p. 8 – 13, 49, 50, 51

– Feature Photographer – Nick White – p. 14 – 19 Photographs on pages – Front Cover, 40, 43, 44, 117

– Canada in Review – Editor – Shane Joseph – p. 20

– Poetry Canada – Editor – Bruce Kauffman – p. 30

– In a Primitive Sort of Way : An essay on five paintings by Anna Panunto – Essay by Richard M. Grove / Tai – p. 64

– A Forty Year Work in Progress , the Niagara Poetry Group by Keith Inman – p. 70 – 84

– CanLit Essays on CanLit Authors

– A Richard M. Grove review essay on: Stronger in Broken Places by John B. Lee – p. 85

– A Richard M. Grove review essay on: Great Silent Ballad by A. F. Moritz – p. 93

– A Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias review essay on: The Great & the Small by A. T. Balsara – p. 98

– A Richard M. Grove review essay on: Scar Atlas by Colin Morton – p. 105

– A Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias review Essay on: Out of Darkness, Light by April Bulmer – p. 110

Photography Curator Mike Gaudaur

After more than four decades of making images that show what something looks like, I am gradually shifting towards making images that show more of what things feel like. I find that the images I capture are more graphic and minimalist. However, I think it is my processing of images that is changing even more. I am less concerned about ensuring that every little detail is clear and sharp, and more concerned about enhancing a mood and

guiding viewers to see just what it was that caught my eye with nothing to distract them. With this collection of images I have been experimenting with colour grading that shifts tones to enhance mood.

Mike has spent the past 12 years teaching photography during school terms and photographing on safari during the term breaks. Online training and countless late nights of experimenting resulted in Mike developing a full complement of digital skills. After returning to Canada he was able to formalize his training and become an Adobe Certified Expert in Photoshop. Mike is a never ending learner, experimenter, explorer. His learning didn't stop with Photoshop. He naturally grew into working with Lightroom, On 1 Perfect Photo Suite, and the Nik Software collection. His advanced skills in the digital technology have allowed him to push his photographic style even further.

You can find Mike at: https://www.mikegaudaurphotography.com/ or contact him by email at, mike.gaudaur@gmail.com

Lancashire, UK

Bearded Tit, England, UK

Red Stag, England, UK

For Nick, a lifelong passion for nature, wildlife and stunning photographs lends itself to a life now spent pursuing wildlife and capturing those moments and the scenery surrounding them. Born and raised in Prince Edward County, Nick devotes his offtime exploring, hiking, and camping both locally and abroad, becoming intimate with the landscape and nature around him. His first camera was picked up at a young age, and was never put down, rather just replaced along the way. He considers himself a lifelong learner, always embarking on a new adventure or career, in search of unique experiences and opportunities to create images. If there has been one constant in his life, it's that he never goes anywhere without his camera.

Since 2022 he has been living in the far north of Scotland and has engulfed himself in the photograph opportunities that have come with being in the United Kingdom. When he is not at sea as a lobster fisherman, he spends his time exploring the whole of the UK and the wildlife and unique scenery it has tucked in every corner of its wilderness and cities alike. From walking among majestic Red Stags in the Scottish Highlands, to quietly observing Barn Owls in the English Farmlands, to wandering the scenic city of Edinburgh, Nick has certainly made an effort to squeeze the most out of his few short years in the UK.

Nick is returning to Canada in the summer of 2025, and looking forward to reconnecting with friends, family, and the natural world he grew up surrounded by. He finds peace and comfort in photographing the wildlife in particular back in Canada that he has spent so many years learning the intricate and intimate details about, that allow him to create images that are in turn intricate and intimate. Never without an adventure in the pipeline though, he is planning and looking forward to trips in the future to the likes of Alaska, Newfoundland, Africa, and Wyoming, to name a few. He would tell you that it brings him great joy to share his images and the stories that accompany them to anyone who takes the time to look and listen.

You can find many of Nick's images, inquire about fine art prints and contact him on Instagram at: @wildly.thick.of.it or reach out by email at: thethickofitphotography@gmail.com

Kingfisher, Shropshire, UK

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 19

Book Review Editor

Shane Joseph

Dear Readers,

Our selection of reviews is smaller in this issue, but eclectic. We are following the principle of “quality over quantity,” a good mantra for the publishing world, given the prevailing misguided one of “more reviews equal more sales,” which leads to countless sales pitches masquerading as reviews and flooding the book-o-sphere.

In this issue we have the works of two eminent Canadian poets, both Poets Laureate of Toronto and one of them going on to become Parliamentary Poet Laureate: A.F. Moritz and George Elliott Clarke. In Moritz’s collection, Great Silent Ballad, reviewer Gordon Phinn “craves to critique, somewhere, anywhere, but is left empty handed and grabbing at air.” And so, Phinn’s review is a pean to a masterful work that cannot be dismissed as a “sales pitch,” but is an expression of genuine affection for a master craftsman and his art. In J’Accuse…!, Clarke comes to the aid of Indigenous women who were raped and murdered by white men, and rebuts accusations made of him in media

and academe for being “guilty by association.” Like with Phinn on Moritz, reviewer Katerina Fretwell, has only compliments for Clarke’s work and his courageous stand.

Moving into the area of novels, we have Susan Statham’s “Agatha Christie comes to Southern Ontario” type of murder mystery, True Image, featuring her amateur detective, painter Maude Gibbons, in her second appearance in ten years. Statham’s novel rises above the standard crime genre because we are given insights into the worlds of Autism and the Painter’s Craft (also the title of her first Gibbons mystery) in addition to the opportunity to wrestle with a typical mystery puzzle. As to whodunit, that is extremely difficult to unravel, as reviewer Linda Hutsell-Manning discovered. Bringing up the rear, is Giller Prize 2024 short-lister Deepa Rajagopalan’s attempt to rescue CanLit’s slide into conformity and mediocrity with her visceral short-story collection, Peacocks of Instagram: Stories, which dives into the lives of the Indian Malayali diaspora in North America. We need more of her kind of bold literature these days.

Shane Joseph Book Reviews Editor

Title: Great Silent Ballad

Author: A.F. Moritz

Publisher: House of Anansi Press

ISBN: 9781487012960

Number of Pages: 144

Published Year: 2024

Reviewed by: Gordon Phinn

It is something of a challenge, suspended in reverence for the stunning achievement displayed by A.F. Moritz throughout Great Silent Ballad, not to come across as some fawning disciple, awkwardly trying to remove the modern and perhaps modish equivalent of bicycle clips. He has long since reserved his spot in the pantheon of philosophical lyricists, winning prizes, honours and fellowships. Modernism, too often shuffled off as the tired grandfather of English poetry, returns, in Moritz’s hands, as some undefeated champion, eager for another round. And I, for one, am glad to see it.

The latest in a long line of sparkling collections—most recently The Garden and As Far As You Know Great Silent Ballad, unfolding its pearls for the patient reader, comes as close to perfection as I have seen in many a year. To spend a month or so in relaxed contemplation of its riches is to live in the lap of rare luxury, revelling somewhat selfishly in its gifts. During the treasure hunt, one uncovers a favourite, and then follows its resplendence in repeated visits, until it seems like home. One is tempted to quote and furnish a room as gem after gem goes the distance, but lines and partial stanzas seem poor clues to the enticing opulent puzzle. The critic craves to critique, somewhere, anywhere, but is left empty-handed and grabbing at air. Analysis, it would seem, reveals only one’s impatience. The whole remains indivisible, a declaration of seamless unity, an enigmatic craft constructed elsewhere, and unveiled only by your eventual embrace.

I say eventual, as one stumbles into metaphorical extensions that seem to be ponderous and at odds with the general flow, but through trust one perseveres and the threads that felt incongruous reveal themselves as construction details in a living whole. One thinks of W.S Merwin, Ralph Gustafson, W.B. Yeats, Hart Crane, Don Coles and other giants of the meditative lyric, and one sees how we are indeed standing on their shoulders, as Eliot, Stevens, Shelley and Hardy did in their turn. Moritz belongs to that company. Am I saying this is depth perception exquisitely rendered? Yes.

One can flip through at random and uncover a neglected pearl and be amazed all over again. Case in point: “The Living Fleet Eternity Of Thought.” Another might be: “In The Motet Of Mondonville”:

“In the motet of Mondonville where the ladies’ voices rise to gloria and tarry there, in that dwelling, so liquid and aureate, is a poet’s anguish and failure to draw out the quickly passing word to its long hidden extent…”

There is no failure here, nor anguish, only exemplary expression of those states that surpass their apparent stasis to seed the secrets of flight.

Though American by birth, A.F. Moritz’s long career as an award-winning poet has been spent in Toronto, teaching, editing and writing. Great Silent Ballad is his twentysecond title. Honours include the Governor General’s, the Trillium and Griffin, fellowships from Guggenheim and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Gordon Phinn has been widely published for decades. A memoir, Moving Through Many Dimensions (2023), while his essay collection It’s All About Me collects his early criticism. A new collection, Joy In Many Genres, is due out in 2025. A current chapbook is Winter, Spring and the Seduction of Eternity.

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 23

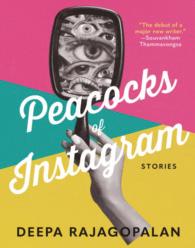

Title: Peacocks of Instagram: Stories

Author: Deepa Rajagopalan

Publisher: House of Anansi Press

ISBN: 9781487012403

Number of Pages: 256

Published Year: 2024

Reviewed by Shane Joseph

Deepa Rajagopalan’s collection of stories made me pause from sinking into the abyss of despair over CanLit’s headlong plunge into politically correct, bland literature. Here was a book that dug under the skin, uprooting warts, even drawing blood, and exposing life in the Malayali immigrant community of North America.

These are women’s stories, women who have been hard done by, by spouses, bosses, boyfriends, circumstances, and their own families back home; women who are expected to grin, bear, and become successes in their adopted homeland. Many of them have broken marriages and relationships, and hover on the pay-cheque-to-pay-cheque periphery. All it takes is an accident, an illness, a sick child, or a transgressing spouse to drive them to the margins. Their community is comprised of STEM workers, mostly in the “T is for Technology” category, imported to the US and Canada and who have gone on to receive permanent residence. None have assimilated, however, for their North American communities are still lavish with customs, practices, and prejudices from the old world.

Some of the characters weave in and out of the stories that take place over the last forty years. Some of them stand out: PKOC (pronounced “peacock”) Lalitha, the bigoted diva of the temple (“How many of these American CEOs are from lower castes? Once you marry a lower-caste man, you change your last name, and that’s it, you are screwed.”); Rahel, the woman who was faithful to her long-distance married lover, before she decided to become one herself with other men; Devi, who works at integrating into America by self-learning to drive a car; Mohak, the lesbian IT worker who gets back at her Issue 020

insensitive employer by fiddling with the company’s computer code; Nilofer, who rebounds from an accident and a crushing divorce to become a potter of pieces that tell the story of her life; and Kala from the title story who makes peacock accessories and sells them on Instagram while earning a living working in a coffee shop.

Rajagopalan leaves these characters locked out of the mainstream, and one wonders whether integration is ever possible for people from strong foreign cultures who come to an open society like North America. Is this why the Indian bridegroom in the story “Live-In” packs his live-in girlfriend off before their wedding because his father is arriving from India to visit? Or why the father grumbles that the Thai take-out food he is eating is, “not fresh enough, but still better than pisa (pizza).”

One also wonders why, with India’s burgeoning economy, these highly-skilled workers still flock to North America to live on the margins. When eight-year-old Raji returns from Canada to Trivandrum for her mother’s kidney transplant operation—because the medical system in Canada was taking too long to deliver—Mother has high praise for the Indian medical system: “The nurse, the reception staff, the techs, everyone was so kind. You get the feeling that they really care. I guess that’s what happens when you can buy health care.” Maybe free medical care in Canada was the attraction, until the shine came off, just like it does with the North American Dream that seems just out of these characters’ reach.

I salute Rajagopalan for re-introducing “bold” to Canadian Literature. I hope more Canadian writers follow her example.

Deepa Rajagopalan is a Canadian writer, whose short story collection Peacocks of Instagram was shortlisted for the 2024 Giller Prize. Born to Indian parents in Saudi Arabia, she has lived in India, the United States, and Canada.

Shane Joseph is a Sri Lankan-born, Canadian novelist, blogger, reviewer, short story writer, and publisher. He is the author of eight novels and three collections of short stories. His latest novel, Victoria Unveiled, was released in September 2024. For details, visit his website at www.shanejoseph.com

Title: J’Accuse...! (Poem Versus Silence)

Author:

George Elliott Clarke

Publisher: Exile Editions

ISBN: 9781550969535

Number of Pages: 208

Published Year: 2021

Reviewed

by

Katerina Vaughan Fretwell

J’Accuse...! (Poem versus Silence) is tough to review dispassionately because the author, George Elliott Clarke, was thoroughly chastised and gravely misunderstood two years ago. Broadcast journalism led the charge, lambasting the poet for refusing to rule out quoting the poetry of a convicted murderer – Stephen Kummerfield, aka Brown –in a public lecture that Clarke planned, hoping to connect Saskatchewan’s white-settler Establishment to the violence affecting Indigenous women and girls. Because Kummerfield used Brown as an alias, Clarke had no idea of his vicious murder, none!!! Clarke learned of that horror in 2019. Though anguished, he was blackballed, blindsided and blacklisted in broadcast and social media. J’Accuse...! is Clarke’s brilliant, multi-genred rebuttal to that monstrous accusation in media and academe of “Guilt by Association”: that by approving of Brown as a poet, Clarke was approving Brown the murderer.

What I detect is lyric genius: onomatopoetic delights, hypnotic rhymes, musical refrains, examples of obscenely lenient sentences for murdering marginalized women and blame-the-victim strategies. Clarke leads the reader on a Dantean journey through hell. One feels what it is like to be blamed, belittled and betrayed, to live with systemic racism; to be violated by an all pervasive white supremacist rule, to watch a lazy media denigrate, denounce, distort and muzzle the now-defamed victim. And I sense a deep empathy – in this poetry – with Indigenous women, people in general, and Ms. George in particular, coupled with outrage against the racism and misogyny that Black and Indigenous Canadians face from the “injustice” system. Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 26

Given his Afro-Metis ancestry, he is particularly qualified to comment on the original “GEC”, (Geraldine Elizabeth Clarke [19392000]), her suffering and that of all her sisters, Black and Indigenous. He protests the murder of Pamela George and the murder of “Africadian” Catherine Wright (Halifax, 1985), and the light jail terms allotted the guilty white men:

This blood-stained “Justice” would set Judas free, Stab down Mary, lynch Jesus from a tree

Throughout this embattled, combative, grisly, and lyrical text, Clarke references, as an alter ego, the Roman poet Cinna who was wrongfully accused of murdering Julius Caesar and torn to pieces by a Roman mob. Clarke’s rebuke abounds in onomatopoetic sounds and rhymes: “This prejudgment (Prejudice) spurred Conniption – / abrupt, corruptive seething – like that Roman mob / that blamed a blubbering poet / for the knives forked slobbering into white-bread Caesar...” This cautionary tale, sweetened by memorable and musical lines, both teaches and delights, and deserves a wide, thoughtful readership. Here’s a final sampling of Clarke’s outstanding lyricism, wit, and anguish: “the skittering indigo green of jittery April field, sorrowful, / thawing into muck.” Skittering and jittery emphasize Clarke’s precarious position and muck is mindful of muckraking journalism; he is also depicting the site of Pamela George’s despicable murder. Scapegoating Clarke is a typical Canadian “blame-the-oppressed-fortheir-oppression” gambit. I concur with Al Moritz: J’Accuse...! is “great poetry.”

George Elliott Clarke, George Elliott Clarke, AfroMetis, was awarded the Order of Canada, Officer. He holds eight honorary doctorates and has won the Governor General's Award for Poetry, the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Achievement Award, International Fellow Poet, and numerous other awards and accolades.

Katerina Vaughan Fretwell’s poetry include Familiar and Forgiveness and Holy in My Nature. Her work, Dancing on a Pin, was shortlisted for the Lowther Prize and was part of IFOA's Battle of the Bards, and Class Acts was a Notable Poetry Book of 2013, Kerry Clare Blog.

Title: True Image

Author: Susan Statham

Publisher: Blue Denim Press

ISBN: 9781998494033

Number of pages: 232

Published Year: 2024

Review by: Linda Hutsell-Manning

In True Image, Susan Statham skillfully combines her talent as a mystery writer and an accomplished artist. Protagonist, Maud Gibbons, has just landed her first lucrative portrait assignment at Barrington Estate, the summer home of wealthy Veronica Barrington. The woman’s employment stipulation is that she will be “painted from life” without the use of photographic reference. As well, Maud must live at Veronica’s home for the duration of the portrait sitting.

Veronica Barrington’s estate holds many surprises, not only in its size and grandeur but also in its occupants. Directionally challenged, Maud loses her way and is unexpectedly helped by Caleb, the weathered handyman who points her in the right direction.

Outside the grand house, she is greeted by Dinah, cook and housekeeper, whom Maud describes as “one of Van Gogh’s peasant women.” She briskly ushers the artist upstairs to her room and snorts derisively when Maud asks where she will be working. A call from Maud’s uncle Sid reveals that Maud also works for him in his detective agency. The next surprise is meeting Jamie, a special education teacher and summer “minder” for Penelope, Veronica’s twelve-year-old daughter who is autistic and never speaks. Jamie mentions to Maud that Penny has a history of being violent if provoked, with no explanation as to what the cause of this violence might be.

Maud has barely started to work on taking photographs as a preliminary to finding the right pose when Veronica’s handsome son, Beau, arrives early. It has been casually mentioned that a birthday party for Beau will take place the following day. Accompanying him is his surprise fiancée, a woman Jamie labels a “punkie-pole-dancing Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 28

prostitute” called Cecilia. At dinner, Penny attacks Cecilia. Beau hurriedly carries her toward his room, demanding his mother immediately call their doctor, Galen.

Several more characters arrive at the party, one being Caleb’s son whose presence becomes somewhat problematic.

The stage is now set, for this tale is, indeed, a murder mystery. We have met the characters and know that one of them must be the victim and one the perpetrator.

The portrait sitting slowly progresses; the party ensues and early the next morning a body is discovered semi-submerged in the pool. To complicate things further, someone has abruptly left the premises.

To identify the killer, mystery writer Susan leads the reader on a merry convoluted chase. Who has been murdered? Who is the killer? Almost everyone except Maud and Veronica Barrington could be considered suspects.

I purposely did not reveal the name of the deceased and I certainly did not suspect the killer although, once it was revealed, I looked back and found earlier clues and comments.

Well done, Susan Statham! Your readers will push on to the end, not recognizing the perpetrator, and when it is finally revealed, will say quietly, “Why yes, of course it was...”

Author of The Painter’s Craft and editor and contributor to six Hill Spirits anthologies, Susan Statham lives in an eastern Ontario hamlet with her husband and their French Bulldog, Arthur Conan Doyle, aka Artie. In 2021, she received Cobourg’s Distinguished Civic Award for Arts and Culture.

Linda Hutsell-Manning’s publications include 13 published children’s books; scripts for Polka Dot Door; a literary novel, That Summer in Franklin; a two-act comedy, A Certain Singing Teacher; a memoir, Fearless and Determined; a picture book, Finding Moufette; and a novella, Heads I Win, Tails You Lose. www.lindahutsellmanning.ca

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 29

Poetry Editor: Bruce Kauffman

Photo Editor: Richard M. Grove

Bruce Kauffman lives in Kingston and is a poet, editor, and promoter. His written work has appeared in anthologies and journals, two chapbooks, and five collections of poetry. His latest, still arriving, launched in late spring 2023. He continues to host a monthly open mic reading series called ‘and the journey continues'. He still produces and hosts the weekly radio show called ‘finding a voice’, on CFRC 101.9fm.

at via kingston waiting for a train to cobourg

waiting at a train station watching a freight train go thundering by as it goes it believes it is steel and strong

i can watch it through windows in the wall

wall there believes it is brickand stone and mortar and strong

but between that wall and me there is a full glass wall dividing and adding a separate space it is glass it is invisible it believes it is air and strong

but as i watch that glass watching me it realizes it may disguise itself as air but cannot yet pretend itself as breath

i still remember here being so entranced by electric cords as thread for the hanging amber edison light bulbs reflecting in now almost infinite rows through a series of glass windows front to back to front again multiplying themselves through an infinite distance and i’m quite certain this reflection is not one of expanding beyond these walls into further space but instead taking me backward and if i squint my eyes just right i realize this instead is taking me back to the beginning of light of time

autumn morning outside

here in this small wooded place just over there there is a ghost in a rocking chair i tell you as you sit next to me you say back you can see the rocking chair but not the ghost i tell you the ghost is smiling but you do not hear me because by now you believe that even i am no longer here

then the light flooded in - 01

then the light flooded in - 02

Alanna Veitch alanna.veitch.av@gmail.com

Kingston, ON

venturing out / One day, you just notice

I’ve grown more reluctant to leave the house, walk farther than 600 feet

You notice these things, eventually slowing down as the walls around your body get tighter

It happened gradually, worse after I got news it could get much worse

One day, you just notice you’ve grown reluctant to leave, to venture out from here

Allan Briesmaster abriesmaster@outlook.com

Thornhill, ON

plowing through tempest and calm, headed steadily on, toward undisclosed shores ...

Not a deluxe cruise from port to resort, this one’s destination not shown in brochures.

The pier of your bright embarkation forgotten, the image of who you once were now a blur, you must simply trust an invisible captain and taciturn staffers to whom you defer.

Perspective … absent. The mere curved horizon; wave on wave, scudding cloud, sky grey or blue.

Interminable interim. … Stock amenities: open buffet, gym room, movie room, pool.

Others aboard mirror your shy uncertainties whether, or how, to try tentative bonding. (Wary of what a too-casual swap of a tale might reveal about little sins pending.)

Could, then, some long-deferred opening-up be in store if our ship ever reaches its goal?

Future kept under wraps. And the present? Devoid of the foresight to lifeboat a soul.

Ana Johnson apj.ajohnson@gmail.com

Kingston, ON

I’m made in the image of the trees, green hues of sunrise. Spring, moulding my blood flow, red cells dancing through my body cradling my pelvis, scapula, shoulders, arms and feet. Verdant shades emanating within pores, sweat moist of moss. Beneath, fresh tender nurturing soil spreading among white blood cells, fighting off anomalies. Ripe grass, blades blowing from wind gusts and soft sways alike, listening to the weather’s wrath and peacefulness. Above, the blue sky, vast and empty, ready for clouds of dawn, gibbous moon lighting up my heart, left ventricle receiving the river of burgundy, right ventricle pumping life into uncoiling leaves of bloom, expectant of the recoiling of Winter snow carved on blue spruce.

Brian T. W. Way btwway@gmail.com

Rednersville, ON

preface: hockey night in canada

the symmetry of the maple leaf is a song that angels sing the grace of orrthe grit of howe or a rocket down the wing

throughout this land since old stans gift from marshy pond to mystic rink desire carved in the heart to hoist that odd-shaped shiny thing

Bruce Cudmore cudmorebk@gmail.com

Rockport, ON

The soft consonants of the English word, suffering, gently convey heavy meaning, levelling human differences as sanding smooths surfaces.

A sufferer feels alone and hears, along with others, how suffer asks to be whispered then sounds like silent, nose-breathed sobs. A verb that allows rather than acts.

Suffering asks to be solved and healed; the suffering ask for the salve of being held. See how suffering ends with the singing ring of a gladly rung bell.

Dinh Le Doan dledoan67@gmail.com

Beaconsfield,

Québec

The sun turns lethargic. It loses its high beam and shines like the moon.

The night’s a giant freezer. Bushes and trees had stopped eating and gone into a deep sleep. Ravaged by hunger they become mere skeletons of their former selves. And the lake lies dormant in winter hiding under layers of snow and ice. Not wanting to be found.

A world in hibernation awaiting the big melt.

Elaine Yu

elaine.yu629@gmail.com

Toronto, ON

The birds’ wings glide across dusk, returning home——

On another planet, in every few minutes, or hours, It comes to an evening.

You have come, and left a line of paw prints and green berries. You watch me flying around, with time’s green grapes in the beak.

Glen Sorestad sorstd@sasktel.net

Saskatoon, SK

The night is breath-takingly clear. We near home after dining with friends and as we begin to round the curve of Lakewood Park on Heritage Crescent, I spot the shapes just below the snow embankment to the left; they plan to cross the Crescent to patrol the pocket park on the other side of the crescent.

“Slow down! Foxes!” I call out to Sonia, who is behind the wheel tonight. The foxes have already made their decision and have retreated, scrambled back up the snowplowed mounds, gained the safety of the sidewalk, where they stand, one beside the other, alert, awaiting a less-pressed crossing of the road.

We roll slowly past the twosome. Intense moonlight and the peripheral reaches of the headlights disclose, even in the dimness of dark winter, the vividness of their red-umber fur, their long luxuriant tails as they stand, confident and easy, in wan moonlight.

Two young foxes watch, patient but cautious, as we pass, then resume their intended crossing, unhurried as foxes tend to be, as they continue their patrol of territory their birth has granted them in this urban neighbourhood of Saskatoon.

John B. Lee johnb.leejbl@gmail.com

Port Dover, ON

the hens were out pecking gravel from the grain in the yard, engaging in an ancient and an atavistic aviary appetite for scree and we who watch and wish to know the lizard from the egg might see ancestored in the beak and flightless wing how Sunday supper gizzarded by kill and corn eventuated to the broadcast and the sweeping hand might craft a fragrant afternoon where oats and barley strike the lawn like sleet in rain and what of us in this gill-weathered tide where crawls the crab and other scuttles of these water-sheltered lives because we’ve lain like sailors washed ashore by changes in the storm

we take a lighter breath to shape a sentient bubble exhausted by the seemingly endless swim since dinosaurs died down to bones because the algae and the milted foam make moonlight green as with a sigh of dream like wind across the shivering wheat we watch the hens the old ones molting at the neck one generation shelling to the next we’ve shed our time-cropped tails beneath the scattered light of stars since when within the womb my mother’s ovum first met my father’s seed an egg tooth out of time the day that broke the yoke within the lime and dust upon the henhouse floor that wickering of straw that fails to mend the dawn until the dark returns where sunlight settles on the earth to warm the nest that isn’t there the water breaks the light and we are born viviparous enough we eat the gloom and wonder at the coming on of ice

K. V. Skene kv.skene@gmail.com

Toronto, ON

I am asleep. I am a dream and follow you to the temple of a god who is you and I understand the impossibility of understanding and swallow my words though you touch my thoughts as you drink the sun and I look at you – look into you flesh could not tear itself from spirit from the kind cruelty of silence and the cruel kindness of dying on this cloudless morning. I climb the winding path as bindweed pleats the hill together and makes its own home where long-ago glaciers gouged out a valley whenever we were lost we held each other – let earth compose its own conditions I am not dreaming. I am awake.

Katerina Vaughan Fretwell kfretwell@cogeco.ca

St. Catharines, ON

That old joke: she looks like a toothpick bifurcated by a bowling ball, describes my 80th birthday coming at me. My turquoise top slopes from two hillocks to mid-mountain before the hem flaps in the breeze.

Veggies, fruit, lean mean protein and Keto bars love to lodge in my belly. Never a bikini-boasting babe, nevertheless, I crave svelte, lithe, lissome.

Arrived at 80, my brittle bones well-muscled and kidneys only mildly on the fritz, I reach up and shake the tree, mulberries slide into my sack and down my neck. Foraging is fun and slivers of pie, irresistible.

I’m thankful being hot is not an issue, too old for hard-hat workers’ wolf whistles ranking hotties or university guys rating gals as we swim team Amazons queued for supper, seniority a blissful plateau.

Robert Currie currie.robertdm@gmail.com Moose Jaw, SK

I study the faces from the residential school, row upon row of children—boys and girls—seated at their desks, their backs ramrod straight, their eyes trained upon whoever took the photograph, the priest behind them, looming like a thunder cloud over false-fronted stores in a shabby prairie town.

These are children young enough that one might expect to see smiles here and there, a spark of mischief in the eye of some small rebel, slumped shoulders on another who’s sick of being told to sit up straight, but everyone wears the same expression, eyes dull, faces serious, not a single smile among them.

These are children taken from their parents, children forbidden to speak their own language. They know about the belt that falls upon them when they fail to follow someone else’s rules.

They sit in silence, their faces blank, resigned, as if somehow they know they may never see their parents again, as if they understand some of them may lie in unmarked graves forever.

Teresa Hall

thallartist@gmail.com

Scarborough, Ontario

Human

I am the many-sided prism reflected in the iris’s light, enigmatic as an enchanted forest’s inner shadowed being.

Unfathomable as indigo layers slanted through oceanic depths, timeless creation of Earth’s own making.

Formed from spirit, water, clay and fire, ethereal, composed of kaleidoscopes of feeling - born of desire.

Aligned with all other living shapes of cosmic stardust, never ending, ever changing.

Scarborough Bluffs - a silent witness - Jan 2025 - 06 Richard M. Grove / Tai

Bluffs - Jan 2025 - 08

Scarborough Bluffs - Jan 2025 - 11

Tai

An essay on five paintings by Anna

Panunto by Richard M. Grove / Tai

From time to time I would see a painting by Montreal, Quebec artist Anna Panunto electronically. We have been FaceBook friends for years but we have never met. In previous incarnations I had been a Gallery Manager and Corporate Art Consultant. For those many years I have admired the unabashed expressionistic style that Anna Panunto uses in her work.

In a primitive sort of way I like these five paintings by Panunto. I am impressed by the raw unpretentious energy of the movement of paint where the painting is not so much about the exact fussiness and perfection of a brush stroke but is more about the mood, the expression of slashes of colour. For me these paintings embody an unabashed expressionistic style that places emphasis on raw emotion over technical precision. These five paintings connect deeply with both the historic lineage of expressionism and modern philosophical inquiries into identity, isolation, and the body’s relationship with its environment. These paintings can be interpreted as visual explorations of such existential themes, offering insights into the human condition through their powerful, primitive forms and deliberate lack of perfection.

It has been decades since I studied art at Ontario College of Art and Art History at U of T. With that background I gained a great admiration for expressionism that emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the rationality and formalism of previous artistic movements, such as realism and impressionism. Anna Panunto carries the mantel of expressionism to a personal obvious conclusion. Dare I make a historical connection to an artist like Edvard Munch who sought to capture emotional and psychological states in his work, often through distorted figures, bold colors, and visible brave brushwork. In Panunto’s work, we see this same impulse: her figures are fragmented, abstract, and roughly painted, evoking the emotional rather than the physical essence of her subjects. This rejection of painterly perfection in favour of mood aligns Panunto with the expressionists, whose work often engaged with themes of alienation, existential despair, and the inner emotional life of the individual.

The rawness of Panunto’s paintings recalls the German expressionist tradition, where the human figure is often distorted to reflect emotional turmoil. In particular, her use of heavy outlines and simplified anatomy is suggestive of the work of Egon Schiele. Like other expressionist artists, Panunto, is not concerned with realistic depictions of the body but rather with how the body can be used to convey deeper truths about human vulnerability and isolation.

Much of Panunto’s work, and most certainly these five painting, can be viewed through the lens of existential philosophy, particularly the ideas of JeanPaul Sartre who emphasized the human condition as one of fundamental aloneness in a universe without inherent meaning. The figures in these paintings, stripped to their most basic forms and often depicted in isolation, suggest an exploration of the self in relation to a chaotic or indifferent world. Their simplified, often faceless bodies highlight the tension between presence and absence, body and mind, reality and abstraction. Sartre believed that art is a way for individuals to express their personal experience of the world. In his existentialist framework, existence precedes essence, meaning that humans define their own meaning through their experiences. Expressionist art, which focuses on intense personal emotions and subjective realities, aligns with this idea. Panunto parallels Sartre’s belief that art is an act of freedom where the artist expresses their subjective experience of the world, often in ways that challenge conventional perceptions.

In one of Panunto’s paintings, for instance, the figure’s posture—a bare back turned toward the viewer—evokes a sense of detachment and introspection. This image is less about the figure itself and more about the space between the figure and the viewer, a gap that suggests emotional or existential distance. This resonates with Sartre’s notion of the “look,” where the presence of another person creates an awareness of the self as an object, fostering a sense of alienation. The blurred, ambiguous backgrounds surrounding these figures further emphasize this sense of existential uncertainty, as if the individual is trapped between reality and abstraction, unable to fully define their place in the world.

In viewing these five paintings one obviously has to recognize that they are all about the recurring element of the female form. Like the work of many modern and contemporary artists, Panunto’s depiction of the female form has to be interpreted as a commentary on gender and the body. The women in these paintings are not idealized; their bodies are not polished or perfected but are instead marked by a kind of raw honesty. This is in contrast to the long

tradition of the female nude in Western art, where women’s bodies have often been objectified or idealized notably for the male contemplation.

In Panunto’s depiction of the woman’s body there is neither a site of objectification nor passive beauty; instead, it is simply a powerful subjectification of form. On some level the female body is no longer female body.

Anna Panunto’s five paintings offer a philosophical exploration of the human condition through their expressionistic style, raw forms, and existential themes. Drawing on the history of expressionism, existential philosophy, and modern feminist critiques of the body, these works challenge the viewer to confront their own feelings of isolation, vulnerability, and identity.

It is not that Panunto intends the paintings to offer clear questions and answers on those existential topics, rather, they invite reflection. The abstract and unfinished quality of the brushwork, combined with the distorted forms, leaves space for the viewer to project their own emotions and interpretations onto the canvases. In this way, Panunto’s work engages in a dialogue not only with art history but also with the individual viewer.

by Keith Inman

Niagara workshops were initially inspired by the book Writing Together by Perigee Books, and the University of Iowa’s great workshops of legendary writers…and the legendary fights among those great writers. Later workshops added rules. The present Niagara group practise those methods and have very few brawls.

We meet in person for the social aspect (and not because someone once brought a double chocolate fudge cream cake with berries). Poems are emailed a week prior, so that folks with busy schedules have time to make notes in comment fields, or scrawl (fairly) legible talking points in margins of copies.

At the meeting, we pick (on) someone to go first. They start by reading their work aloud. Then, after a prolonged silence, where the reader gets all twitchy and upset (more on this later), a discussion begins.

An item of note here is that the presenter does not proffer an explanation of their work, unless they are asking for a specific critique. The idea is to keep the reading true, or, as the book states, ‘pure…how a reader would receive the work.’ Strengths and weaknesses are then discussed in a positive manner, such as: “The rhythm of the piece is fascinating because of the repetition.” We also like to be honest: “in verse two, line three, it’s not clear who is speaking.” If something isn’t working, we bring it up openly, and respectfully (after all, your turn is coming).

Another pesky rule we follow is that the author stay out of the fray, like a fly on the wall (and not on the cake). They must not defend their work. That is not what our workshops are about, and, it would interrupt the flow. Evaluation

of all positions is the group’s job. The point is to create a dialogue. It is comparable to sitting on an editorial board. Besides, comments are only suggestions. The presenter may accept or refuse any or all as they wish. It is their work. They are the final editor before submission to a publication. And, these comments are from fellow writers; interested readers; a studious (if not professional) audience. The process is invaluable for all to understand how poetry sings. Our aim is a friendly, safe and respectful environment for all members and poetic styles.

Now, about that prolonged silence I mentioned earlier. We find it important to speak soon after a poem is presented. That twitchy business isn’t nice, especially with handfuls of cake in the room.

The Niagara poetry group is made up of Keith Inman, Mori McCrae, Gary McCarty, Carla Hartsfield, Susan Smith, Brenda Schultz, Katerina Fretwell, and Kaitlyn Langendoen.

Here are some of their poems:

Brenda Schultz brendamary520@gmail.com

St. Catharines, Ontario

Ink Galleries

I determine to depart the poetic archives for a now poem – What’s poetic now? Ah, ubiquitous tattoo art — not about drunken sailors anymore. And so, I observe, I delve.

I learn about this man who has a lifelong obsession with pirates. Body covered with swashbuckler symbols and a sailing ship on his back.

I delay the young tattooed man outside the grocery store, who delights in giving me a tour of his arm garden and the picturesque angel protecting him. Not just for bikers anymore, but professionals too he explains. It’s leading-edge art.

Stunning Carolyn comes for dinner.

I’m eager — she has tattoos. She tells me about the warrior goddess that empowers her, the skulls and patterns flowing down her arm. I have many more on my body, she adds.

I recall the wedding, the gorgeous, athletic bride with abundant tattoos, the various guests, some totally encompassed, others with a few. All have a story to tell, a palette they proudly share.

What’s it about — culture spirituality passion rebellion a rite of passage? What I once despised, I now devour with curiosity.

Katerina Fretwell kfretwell@cogeco.ca

St. Catharines, Ontario

“Mother Nature’s In Menopause”

— Quote from Patricia Griffiths

Her art, stillborn words –she crinkles her maple skirts during a hot flash, fiery breath flaring across the globe.

Two Monarchs briefly air-kiss before tethering onto Susans’ black centres pop-eyed in estrus.

Sunflowers face downward, heart-shape leaves itchy as rags for monthly menses.

Clouds tremble in the scowling sky, winds suctioning cumulonimbus, blowing away life drop by drop.

Even squirrels flop down after halfhearted flirting, too tired to romp on tree torsos.

Dreaming of wetlands, yellowing grasses wave Help as their arid carpet dehydrates subterranean creatures, gasping for breath.

No apples no alpaca, no birch no bees, no corn no cod, no daisies no dogs... land and sea a barren womb.

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada

Mori McCrae mori.mccrae21@gmail.com

St Catharines, Ontario

Breasts like hers are found only in antique paintings from the Netherlands, in depictions of small, firm, Flemish jugs of cream —

not sure she belongs at the Dollarama on Scott Street, hair worn loose and long as she adds up my items: boop boob boop next comes, of course, the exchange of plastic for plastics.

She gushes then, all smiles and sighs: Oh well, don’t tell, I forgot to scan your cups. Anyway, she whispers, I hate working here, it’s just the customers I love.

And you know you’re capable of worse than shoplifting, to play along with little collusions of youth, how else would you take your coffee, black, and bitter?

Susan Smith essaysmith69@gmail.com

St Catharines, Ontario

Once I strode the world at the speed of thought on my two good legs. At three-quarters of a century, an inherited sidewinder spine fulfils its threat, turns my carefree stride to a tangle of worn-out tendons.

I no longer swell to the triumph of that rhythm or eat distance airily as breath.

But what else do I know?

I take distress for a walk, stump with my cane, slow and pained, through the muted cloister of sycamores arching high across Overholt Street.

These impassive elders slide imperceptibly along a different plane of time, their sufferings likewise boundless — great wounded boles and bare sockets where branches ripped away, roots like boa constrictors jammed under concrete.

Far above me, they rustle their last autumn leaves.

Suck it up, darling, they say.

Did you really believe sentience came with nothing but a stream of pleasures, happy ending guaranteed?

You are here. And you feel it.

Have you any idea the odds that a fallen seed makes a tree?

Carla Hartsfield cjhpianostudio@gmail.com

St.

Catharines, Ontario

My heart is still beating, but it’s no longer a part of me. It has taken the form of a velvet settee where I sit inside the gallery—not exactly heart shaped, more of a bloodied plush clover.

No true lover could endure this exhibit: the chorus of Degas’ frilly dancers, gauzy, out of focus. Ah, the tulle!

Robbers have cut screen after screen from house windows worldwide, ruffled them up, bent them into tutu skirts. And here they are, whirling on these robo-ballerinas, buzzing, existential eggbeaters.

I’m annihilated by Degas’ lack of clarity— dizzied by his dresses spinning like tops, the dainty, petal feet, satin rippling on canvases.

And when I pull on a shoestring or heartstring or puppet string, something is lost.

The ballerinas want to keep romance alive with dance positions, bind the bonds of couplehood tight to this garish settee impersonating my heart.

Their petit-point steps stitch an inner pas de deux.

The little dancers bow.

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 79

Keith Inman inman@vaxxine.com

Thorold, Ontario

— for Leonard Cohen and Marianne Ihlen

Your memory played the distance thin, a major sharp, a minor flat, but you drew all the dark chords to ya, didn’t ya. In an age of light you struggled forth hammering on a dais floor singing of a lonely Hallelujah.

Well, some said that choir’d sung before among the shadows, the refuge there, ringing and heaving the rafters. Yet the spire stood, the stained glass held as voices joined through open doors, and we all cried out our HALLELUJAHS!

But now a light shines down the hall. It flickers off the garden wall not just on your face by the candles. Where love is strong and calls out loud, a weaving crowd sings it proud in a rising chorus of Hal-le-LU-JAHS.

Because in the end, the letters you’d sent came back to you from a quiet heart battered and bruised as yours was. The tide had come; the waters’d shifted; her hair and eyes drifted blue to grey and we whispered, “Aging is hallelujah.”

And maybe there is an island there above the clouds where you sit in prayer turning beads at a gate of white pickets as hands reach out across the sky, evening falls and crowns the night; it is holy, and breathless, hallelujah.

Kaitlyn Langendoen katylangen07@gmail.com

St. Catharines, Ontario

I, as Nature is Nature Primeval: My connection to you is naught, You say; animals entwine the ecosystem. My body is nothing, just as you say It is to take, though an essence escapes. My prequel? A darkness, you claim, Like the gaps of planets and space. Yet, That emptiness there, hear me please, This is your responsibility, your energy.

Consider our Conception:

My life opens at the pollination of two Atop the dirt, just as you first ensued. My growth sustained by the tilt and Turn of an Earth, replenishing your food. My parasitic symbiosis an example Hearts cording to wombs and wombs waking, My lakes of algae feeding your fish, Like your muscles bending to pump blood.

I’ll only, for so long let my birds bother To eat bugs and arachnids to save your skin.

For you forgot sustenance: You forget, though I am green, You were too, were once so in tune. Your inhale, your breath, Was the exhale of trees, now dead. Your sweat the condensation of rain, My drops your drink, now dry. Your beat of life a harmony, bio frequencies, My song your pulse, now silent. And at your feet, where you close, I commenced, until into that grass you’ll blend

Because at your end I begin; your insides Will inevitably expel what you took, Your dead skin will dissolve back to clay Becoming the dust of my ground. Your blood will be drunk as the water source Of my tree roots and orchard fruits. Your organs will be eaten by worms Who carry the nutrients back to flowers, to bees. For we complete the ecosystem, and we Cannot, will never, unentangle you from me.

Gary McCarty gmccpoet@gmail.com

Crystal Beach, Ontario

They stand in front of me, facing me. I return their gazes and then look beyond them, to the distant horizon. They are there. All that is beyond the immediacy of them is part of them. I can be with them even when they do not stand before me. The stars exist even when the sun is bright.

A Review Essay on Stronger in Broken Places

by John B. Lee

Published by Aeolus House – www.aeolushouse.com

ISBN – 9781987872668

Review by Richard M. Grove / Tai

Stronger in Broken Places by John B. Lee is a powerful collection of poetry that explores the lifepunctuated themes of resilience, loss, and the human condition. John often manages to unravel the riddles of life in an amusing and entertaining way, though be prepared to ponder and contemplate as you read. This is not what I would call a fun quick read. I read almost the entire book in one poem sittings.

The book starts us off with a not so cryptic smile with the poem “How Do Humans Make Humans”. As I get started writing this essay I am smiling at the innocence of the sixyearold’s not so audacious question:

“Grandpa, how do humans make humans?”

I have known John for decades, part of my smile is at the naiveté of the question but the other half of the smile is because I can see Grandpa John squirming with his feet dancing under the Christmas dinner dining room table wondering how to answer the question.

I talk of trees and of the pollinating drones of male and female in every species of mammal of dogs and horses of men and women of fathers and mothers

I love how John finishes the poem: and everywhere lovers like seed kites explode on the wind like the grass that catches the snow

On one level this is a fun and whimsical poem that makes one smile from line to line, but on another level it causes the reader to pause and reflect on the many layers of life’s riddle of who we are and how we came into being.

While unraveling the riddle of life for us, John jumps from the gentle humour found in the first poem straight into the touching but solemn look at life and death with the second poem “On the Night of My Conception”. John begins with a somber glance at an urn on the mantle with mother’s ashes.

on the mantle in my study I have a crystal cruet on a shelf a sacred vessel for a portion of the mortal ashes of my mother

but even here as he looks at his mother’s death, he plunges the reader into a whimsical swirl with these lines:

and if I think of her within my father’s loving arms the night of my conception in a swirl of sperm

Overall, I would say that the collection is deeply introspective. John delves into personal and universal experiences of grief, love and the passage of time.

The poems are rich with imagery and emotion, reflecting John’s thoughtful and reflective connection to nature, memory, and the spiritual aspects of life.

John and I have a similar sociological and geographic upbringing, both of us in our early 70s, both with a family farm background in Southwestern Ontario. I immediately identify with much of his imagery that is rooted in family and landscape. His poems are so often infused with a sense of place that is both intimate and expansive.

Here are just two examples of both an intimate and an expansive sense of place. An intimate sense of place can be found in “My Love with Her Pocket Full of Glass”. The intimate setting is created through the detailed and personal description of his wife’s ritual of gathering beach glass. The focus on her actions, the texture of the glass, and the final placement of the collection in the window well at home, evoke a deeply personal and intimate space. Thanks for these wonderful lines John:

inspects her find then fills her cotton pockets with those broken coins one shell for company one granite pebble and one fossil, all of it for the window well at home

A wonderfully expansive sense of place swims in the poem “Ode on First Spring Sighting of Coots at Silver Lake”. This sense of place is so expansive I feel I have kayaked and skimmed across the surface of that very swamp. These lines drew me in:

on the shiny surface of the swamp polished smooth by the luminous darkness of daylight’s deepening like night‐blackened glass

But then in the same poem John, in his brilliance, will turn us on our head with an intimate silent view of a muskrat swimming:

and then like widow’s gauze stirred by a breath without sorrow the wet wrinkled V appeared in the wake of a muskrat swimming through the blur of carp milt

and then he takes us back to the expansive sense of place. This back and forth is part of the brilliance of this poem. How much more expansive can you get than with these lines?

come to me by way of this lovely apparatus like the stars in a midnight meadow mirrored in the glass of the mind o Andromeda I see you and I hold you in your second heaven behind closed eyes

Both of these examples showcase the contrast between John’s observation of the closeup view of an intimate, personal ritual and John’s broad, wonderfully sweeping depiction of an expansive natural landscape. John has brought life to both observations that some might not have even noticed.

The structure of the book allows readers to journey through a range of emotions and reflections, with each poem offering a unique perspective on the struggles and triumphs of the human spirit. From the tenderness of childhood memories to the harsh realities of loss and mortality, Lee’s poetry is a testament to the enduring power of hope and the resilience that can be found in even the most broken places.

In addition to the themes of personal struggle and growth, Lee also touches on broader societal issues, including war, poverty and the environment. His poems often carry a sense of urgency and a call to action, encouraging readers to reflect on their own lives and the world around them.

So now let’s jump deeper into the book for a moment to the eponymous title “Stronger in Broken Places”. The title is drawn from a quote by Ernest Hemingway’s 1929 novel, A Farewell to Arms. The full quote is: “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.” In some obvious and often not so obvious ways both the book and the poem

deal with the idea that suffering and adversity can lead to greater strength and understanding.

It has been decades since I read A Farewell to Arms but I think that Hemingway was reflecting on the nature of human suffering and resilience. The idea is that life, inevitably, subjects people to hardship and pain, often causing emotional or psychological breaks. However, for some, these breaks lead to a kind of inner strength that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. The broken places where people have experienced pain become areas of resilience, where they grow stronger as a result of their trials.

In John B. Lee’s poetry collection Stronger in Broken Places, he seems to suggest that the poem and the entire book will explore the themes of adversity, recovery, and the deepened understanding that comes from overcoming hardship. In an esoteric way, Lee’s work echoes Hemingway’s belief in the potential for people to emerge stronger from their struggles, finding resilience in the very places where they have been hurt.

I had to read this poem about ten times for me to get a full grasp and appreciation of the subtle significance of some of the lines. I don’t want to scare the reader with my slow ineptitude but this is finally what I digested after all of those readings. I might not have persisted if it was not such a dynamically interesting poem with so many beautiful lines.

I found the twoword line, “out there” to be a haunting start to the poem, particularly because it was right after the provocative title, Stronger in Broken Places. That twoword line is followed by the beautiful imagery that evokes the serene yet perilous edge of a frozen lake.

For me the poem is a haunting exploration of loss with a delicate balance between beauty and danger in the natural world. John juxtaposes the imagery of a serene, picturesque setting with the tragic event of a boy drowning in the lake’s waves.

out there just beyond the edge of ice where the blue beauty of moving water begins to shoulder over the white line

is the very place where the boy was lost to the slow shrug of a seventh wave

John follows those stunning lines with these two lines that literally made me shiver remembering a time when I plunged through the ice to my almost death.

and shivering over his small body

At the risk of rambling on too much about this striking poem, let me continue by saying that the poem reflects on the relationship between humanity and nature. The photograph of the Cuban father and son (by the way, I am pleased to say it is my photo John is making reference to) in the final stanza serves as a counterpoint to the earlier tragic scene. The photo reference suggests that the sea is still a powerful force, but it is regarded with respect and wonder rather than fear. The “dark tracings on the sand” suggest that while the father and son are connected, their shadows—their presence—are fleeting and impermanent, much like the boy lost to the lake. The final lines,

what receives the light in everything lies just beyond their reach,

echo the idea that there is always something elusive, something beyond our grasp, whether it is the light, our understanding, or the forces of nature. The overall tone of the poem is contemplative, somber, and reflective, with a sense of mourning. However, it is not without a glimmer of hope—the possibility that, despite the tragedies we face, there is strength to be found in our brokenness. I can’t say all of this and not give you the entire poem so here it is.

out there

just beyond the edge of ice where the blue beauty of moving water begins to shoulder over the white line is the very place where the boy was lost to the slow shrug of a seventh wave shawling up and shivering over his small body with an undulating drag like wet chain as link by shuddering link the cruel‐fingered lake became a last seduction of foam and frozen froth and a shaken jigger of shattered ice sizzling in the deep beyond all reach like embers hissing as they die and he was swept away waving as an old horizon might wave in distant shores that receive the dying light of day

and I wonder then are we also stronger in broken places as we are when snapped bones knit if we ask the threadbare spirit where it’s worn most thin by the big questions we are sometimes used to ask

on the wall at home I have a photograph of a Cuban father standing tall beside his little son their hands both linked in loving their shadows cast dark tracings on the sand as they regard the beauty of the Caribbean Sea and what receives the light in everything lies just beyond their reach

Over all, I have to say, the poem is a powerful meditation on the fragility of life, and invites readers to reflect on their own broken places and the strength that might lie within them. All that said, I have to simply say thanks John for the poem. Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 92

A Review Essay on Great Silent Ballad

by A. F. Moritz

Published by Anansi – www.houseofanansi.com

ISBN – 9781487012960

Review by Richard M. Grove / Tai

One of the first things that I should comment on about A. F. Moritz’s Great Silent Ballad, is the irony in the title, a thoughtprovoking choice that juxtaposes the inherent qualities of a "ballad" with the notion of "silence." Traditionally, a ballad is a narrative song or poem, meant to be spoken or sung aloud—a form that communicates stories often filled with emotions and even existential truths about life. The idea of a "silent" ballad is then paradoxical; how can something meant for expression and performance exist in silence—except that the silence is an inner silence of contemplation.

This irony is deeply connected to the themes in Al’s work. Great Silent Ballad engages deeply with the theme of silence, particularly in its exploration of poetry as an unspoken yet powerful force. The poem "Word and Silence: After Neruda" explicitly addresses the contradiction of language and silence:

“The word was born in the blood and grew up in the dark body, pulsing. ...

I say it and I am and that way alone I move near, nearer and nearer, to its silence.”

It seems to me that Al is reflecting on the origins of poetry and language, connecting it to both the physical and the ineffable. The poem acknowledges that words emerge from darkness and ultimately strive toward silence, a silence that holds meaning beyond articulation.

Similarly, in "A Meditation", he explores the tension between stillness and the eruption of poetic inspiration:

“I sat down to still myself, arrive at no mind, and await the coming of the voice of the spirit or the presence of nothing. ...

Then there came a poem. Then there was nothing left...”

These passages reinforce the interpretation that Great Silent Ballad presents poetry as an essential yet quiet undercurrent in human life. Al does not portray silence as a mere absence of sound but as a presence, a force that permeates existence and allows poetry to emerge in its most profound form.

This collection presents poetry as a basic but often unacknowledged force in our lives, a silent, underlying truth. In the book, Al frequently explores how poetry is a vital and primal element of human existence, even when it goes unrecognized. The "silence" in the title suggests poetry’s quiet yet persistent presence in our lives. In calling it a "silent" ballad, Al may be implying that poetry holds immense significance not through loud declarations, but through its subtle influence, like an unvoiced truth resonating within.

The poem "To Those Who Like to Say 'I'm Not Much for Poetry'" explicitly embodies the idea that poetry is indispensable, yet is often an undervalued force that inhabits us, a silent truth always present.

“You don’t live if there’s no poetry: you don’t live at all, or if you appear to yourself to be living, you’re not. You really are living, though, even if you’re dead, because you do have poetry, poetry’s with you whether you know it or not, whether you think so or don’t. Poetry’s there in the earth and waters and light and wind, a shelf too high for you, bawling child, even to see what’s on it, but there are always people who, for some reason, love you so much that they hand it down for free.”

This poem directly asserts that poetry is an inherent and vital element of existence, even when it goes unnoticed. Al portrays poetry as something beyond conscious recognition, something embedded in the very fabric of nature and human experience. The metaphor of poetry as a "shelf too high" suggests that its significance is often beyond immediate grasp, yet it is always there, waiting to be discovered or gifted. This aligns with the notion that poetry operates as a silent, fundamental certainty, always present, shaping human experience, and deeply connected to life, even when unrecognized.

With poetry's role as a sustaining power at its core, Great Silent Ballad is a rich, contemplative work exploring themes of existence, memory, and hope. The collection is meditative, visionary, and philosophical in tone as it examines the intersections of personal and cosmic experiences.

One of the thematic directions that particularly resonated with me is Al’s deep reverence for childhood and human development that is connected to the ever presence of hope and love. Al often contrasts the timeless, original aspects of poetry with the transitory nature of contemporary civilization. This tension, indicating that poetry is both a response to and an antidote for modern existential despair, is woven throughout the collection, as Al positions poetry not merely as an art form but as a means of connecting to fundamental reality.

One poem that strongly reflects Al’s deep reverence for childhood, human development, and the presence of hope and love is part 8 of the 9part poem “Adolescence”, which contains one of the many repetitions of the phrase “when I was a child” that occur in Great Silent Ballad:

“When I was a child, there came a time when I looked up and around. No more playing now, no more swinging my fist in soft blows, all that my pretty rage could do in the lost endearing kittenhood. I find myself big now. One of the big people.”

This poem captures the transition from childhood innocence to the identification of one’s power and responsibility in the world. Al presents this shift as a moment of both loss and selfawareness, an awakening to the fragility of human life and the ethical weight of existence. Issue 020

Another striking example is "The Dusk", which situates a child in solitude, discovering an inner peace and an awareness of the goodness in the world:

“A child is in the house alone. The other howling snatching children and the big people all are gone.

The dusk of struggle keeps increasing. He grows the knowledge of the good.”

For me it appears that this poem portrays childhood as a formative space where one encounters solitude, the beauty of the natural world, and an emergent understanding of life’s fundamental truths. The child's solitude becomes a moment of transformation, where the external world’s noise fades, and an inner realization takes root. The natural world—the dusk, the fireflies—acts as a reflection of the child’s evolving understanding, linking the sensory with the philosophical.

This poem views poetry not just as artistic expression but as an association to a deeper, crucial reality, one that counterbalances modern existential despair. Both of these poems emphasize poetry’s role in preserving the primitive, unspoken truths of human experience, reinforcing its quiet but acute presence in us.

In his stylistic choices, Al employs vivid, often stark images that ground abstract reflections in tangible scenes. The poem “Beyond” is a good example:

“During that sweet time when there is no death there’s always someone dying, somewhere, outside. And maybe not. I can’t be everywhere. I don’t know. Simply the mind’s eye goes to what is known from getting accustomed to the earth: anguish.”

Here, Al juxtaposes the fleeting nature of life with the everpresent shadow of mortality. The opening line presents an apparent contradiction, a moment of peace that is always interrupted by death elsewhere. His language is both evocative and direct, anchoring the philosophical meditation on life’s impermanence in a simple yet profound statement.

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 96

Al’s use of nature as a mirror for emotional and existential inquiries is evident in “A Flower Giving Names to Eve and Adam”:

“Here is this striking flower, love—what shall we call it? We came out here and tramped these unbound meadows... If we want to call this thing or recall it between us now... we’ll have to make it a name of our own.”

This poem connects the act of naming with the human impulse to make sense of existence. The flower, an ordinary yet symbolic object, becomes a metaphor for language, memory, and personal meaning, reinforcing Al’s idea that poetry itself is a means of shaping and understanding reality.

These examples illustrate how Al’s style consistently blends vivid imagery with existential and philosophical musings, making his reflections both accessible and deeply resonant.

For me the Great Silent Ballad was a wonderfully contemplative read. It offers readers a layered meditation on existence, rooted in the beauty of language and the transformative power of poetry. The collection is an invitation to ponder the deeper facets of life, using poetry as a guide to navigate the human condition.

From a sister publication see The High Window: https://thehighwindowpress.com/2024/08/01/afmoritzgreatsilentballad/ Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 97

A Review Essay on The Great & the Small

by A. T. Balsara

Published by Common Deer Press – www.commondeerpress.com

Review by Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias

For almost a decade, I have systematically written and published reviews and essays on Canadian poetry, occasionally using my modest skills to comment on prose as well. The amount of authors and their works, both poets and prose writers, I have dedicated time to is significant considering the vastness of the Canadian lit mosaic. Such vastness never exhausts; it is continuously expanded by names adding worth and wonders to its territories. One of these names is Andrea Torrey Balsara (aka A. T. Balsara), author and illustrator, whose imagination and competency as a writer surpasses limits, engages readers—children and young adults, whose ages pose an extra challenge for any author—and handguide them into fantasy realms with a virtuoso knack evident since the moment we start reading her stories. This is not my opinion alone. The book I am commenting today, The Great & the Small, Common Deer Press, is a 2024 awardwinning YA novel, second edition.

How do I start my review? What specific passage at the beginning of the story catches my attention and I can share it with my readers? Let´s try this one,

“The everpresent stink of the Lowers hovered in the air

like a brown fog, but she didn’t care. Maybe here, at the end of nowhere, she and her baby could be safe.”

Even though Balsara opens the story distinctly introducing her fable character, a rat named Nia, the above quote, taken out of context, acquires a meaning that applies to humans. Reread the quote and you will feel it too. It is more than obvious that danger is in the air, a presupposition that becomes a fact a few lines later. Isn’t there danger everywhere? Grudges? Bad blood? Resentment? Above, in human land; below, in the tunnels of the rats—much more: danger in these worlds clashing, which replicates colliding societies? The writer skillfully knits words and sentences setting up a rather suspenseful atmosphere that grabs the readers, who move further to read what Balsara presents as the parallel worlds they are about to step into,

“Watching over all of this, under the faux Gothic clock, stood MiddleGate’s most famous tourist attraction: a brass statue modelled after the gargoyles of Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral. To the people of the Middle Ages, gargoyles were talismans against evil. To the people of MiddleGate Market, they were a curiosity.”

She uses comparison and contrast as techniques that will situate the reader,

“This was the side of the market the tourists saw and the locals loved. They had no idea of the other side, the one that lay below. A distinct world, with its own ways, its own rules: a colony of rats. Tunnels wound underneath the hill, toothcarved thoroughfares, veiled from the eyes of humans. There were tunnels high up and tunnels below that snaked deep into the hill’s belly.”

From that point on, a series of events unfold almost like lightning before the readers´ eyes. We all are caught in an adventure that rocks us back and forth the world of the “TwoLegs” and the world below, both temporally and spatially. This transition hits a keynote stage in a particular fragment where the human character, Ananda, is confronted with a complex situation. The circumstances unleash a new onset of emotions and occurrences, “… the fishmonger barrelled past them and ran into the street, chasing a flash of white and grey. A mouse! (...) The man slammed his boot down. He missed its body but caught a paw. The mouse squirmed in pain, its back paw crushed (…) Rage rose through Ananda’s body and erupted from her throat. “STOP!” she roared. Flailing against her father and pushing him away, Ananda leaped between the man and the mouse. “Leave it alone!” she screamed.”

Readers will realize of the use of italics in some lines to represent the voice of an animal (HELP ME!) or human thoughts (“Foot crushed (…) Foot crushed. Agony (…) Safe. Finally safe”). Alongside, the use of capital letters to reveal more graphically for the readers states of mind and burst feelings, the use of colloquial, even vulgar (obscene) language, contractions and the use of interjections and exclamatory words. All these literary resources employed altogether grant the context in which they are placed a highly emotional connotation (necessary to attract readers), and reflect a typified kind of communicative milieu and cultural background. All of them are resorted to by authors as excellent tools, “as conventional symbols of human emotions.” (Galperin, 1981). In the novel, it applies to animals too. There are many examples in the book where Balsara adeptly maneuvers with these language devices,

Issue 020 Devour: Art and Lit Canada 100

““NO!” she shrieked. A crowd was gathering. “Wha . . . are you nuts?” the man sputtered.

“ANANDA!” Her father again. She shook his hand off. Pain that wasn’t hers numbed her leg (…) “I oughta sue your ass!””

I have offered the reader so far what I think are substantial moments in the story, moments which give coherent shape and perspective to the spirit of the narrative. Balsara crisscrosses the “ontop” world and the “downbelow” world with an intentional penmanship that captures the readers. We now know where we are standing amidst the skirmishes of humans and animals.

It is my contention that young adults (and not so young!) will relate to the story in many ways. Not only does it propose varied dilemmas we face on a daily basis in life; it also, and most importantly, helps us understand the intricacies of the growing human mind and the circumvolutions of society and its scourges.

Once Ananda is whisked away from the street wrangle, her father tries to teach her a raw lesson of life with what he asks her to read,

“Wild rats carried fleas, which carried plague bacilli. Her hand covered her mouth. Ananda knew what had happened the last time a strain of the plague “terrorized” people. She’d recently read about the “Great Mortality” of the 1300s, and even more recently the world had just started to recover from Covid. Another plague couldn’t be happening again!”