Buddhist Ethics: A Philosophical Exploration

Jay L. GarfieldVisit to download the full and correct content document:

https://ebookmass.com/product/buddhist-ethics-a-philosophical-exploration-jay-l-garfi eld/

Visit to download the full and correct content document:

https://ebookmass.com/product/buddhist-ethics-a-philosophical-exploration-jay-l-garfi eld/

Jan Westerhoff, University of Oxford Series Editor

Illuminating the Mind: An Introduction to Buddhist Epistemology

Jonathan Stoltz

Buddhist Ethics: A Philosophical Exploration

Jay L. Garfield

How Things Are: An Introduction to Buddhist Metaphysics

Mark Siderits

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–090764–8 (pbk.)

ISBN 978–0–19–090763–1 (hbk.)

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190907631.001.0001

1

Paperback printed by Marquis, Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

For Guy and Steve, kalyāṇamitras, In gratitude for over 3 decades of friendship and collegiality

And in recognition of lives that so beautifully exemplify Buddhist moral ideals

We are talking, we are driving

And in this moment we are denying

What it costs, what it takes

For one perfect world

When we look the other way.

Indigo Girls, “Perfect World”

This volume is one of a series of monographs on Buddhist philosophy for philosophers. In Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy (OUP 2015), I argued that Buddhist philosophy can enrich contemporary philosophical discourse. The volumes in this series are attempts to introduce Western philosophers to Buddhist thought in specific philosophical domains, such as metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of mind, etc., in order that they might be better equipped to address Buddhist literature and to consider Buddhist perspectives in their own philosophical reflection. This volume presents an outline of Buddhist ethical thought. It is not a defense of Buddhist approaches to ethics as opposed to any other; nor is it a critique of the Western tradition. Moreover, it cannot pretend to completeness or to depth: Buddhist philosophers have been thinking about ethics for 2,500 years, have developed diverse ways to address ethics, and often disagree among themselves, just as Western ethicists do. This volume can only provide the broad outlines of that project.

My aim is to provide these outlines, and to present Buddhist ethical reflection as a distinct approach—or rather set of approaches—to moral philosophy; while I do not pretend to completeness, I deliberately draw on a range of Buddhist philosophers to exhibit the internal diversity of the tradition as well as the lineaments that demonstrate its overarching integrity. The integrity and diversity are each important. The Buddhist intellectual world, like the Western intellectual world, is heterogeneous, and it is important not to generalize too hastily. Nonetheless, there are overarching ideas and approaches to moral reflection that give Buddhist ethics a broad unity as well, and I aim to articulate that unity despite the diversity in detail. Where intramural philosophical differences are important, I will note them; but many of the ideas I am articulating are either common to many or most Buddhist traditions, or are at least suggested, and constitute a reasonable rational reconstruction of a broadly Buddhist approach to ethics.

I emphasize that this is an exercise in rational reconstruction. It has to be. Neither Indian Buddhist philosophy as a whole nor Buddhist philosophy, per se, distinguishes ethics as it is understood in the West as an independent

domain of study, and Buddhist literature that addresses ethics does not do so in a metaethical voice. The metaethical commitments that lie behind ethical thought in Buddhist literature must therefore be reconstructed and tested against textual material. Many of the formulations I offer will not correspond exactly to how things are put in any single Buddhist text, although they will be grounded in readings of a variety of texts. My goal is thus to provide a more systematic presentation of Buddhist ethical thought than is provided in the Buddhist canon. At times I will be reconstructing the implicit theoretical perspective of a single philosopher, text, or school; at others, I will be presenting views I take to be implicit in the tradition as a whole.

My approach is to remain faithful to the ideas articulated in the texts I address, but to be philosophical, not historical or anthropological. So, the fact that some of what I say might be rejected by some canonical Buddhist philosophers, some Buddhist practitioners, or some scholars of Buddhist studies does not necessarily count against the broad picture I am painting. Just as we would not write a treatise in Western ethical thought by observing the behavior or intuitive ethical commitments of a sample of European and American people, but rather would consult the texts on ethics written by philosophers, I will not be surveying the practices and beliefs of a range of those who identify themselves religiously as Buddhists; instead, I will be addressing the texts written by or taken as reflective touchstones by important Buddhist philosophers.

I reject the strict dichotomy that some draw between “classical” and “modernist” readings of Buddhism, a dichotomy that often leads to valorizing the ancient as canonical and disparaging contemporary Buddhist theory as merely Buddhist modernism. I take Buddhism to constitute a living tradition, and while I will spend most of my time with very old texts, I will address the work of recent and contemporary Buddhist philosophers as well. I take 21stcentury Buddhist thought to be no less a part of the Buddhist tradition than 1st-century Buddhist thought, and I hope to represent not only the diversity but also the progressivity of the tradition. So, once again, the fact that a recent interpretation or idea goes beyond—or even conflicts with—classical formulations does not, in my view, constitute a reason to ignore or to reject it.

This presentation is not comparative. That is, I do not systematically identify Buddhist ideas with Western ideas; nor do I systematically contrast them. I think that the comparative approach to philosophy is passé, and that it tends to distract us from the task of engaging with another tradition on its own terms. I therefore simply present Buddhist ethics to the reader as

I understand it, adopting a voice meant to articulate the tradition, or at least certain parts of that tradition relevant to the perspective that Buddhism gives us on ethics. My approach is grounded in readings of texts that I take to be central to that tradition, in the hope that by doing so I can introduce a distinctive voice to contemporary ethical thought.

Nor is my survey of the tradition complete. That would be impossible, given its vastness. For one thing, as this is a philosophical investigation, I have confined myself to written textual resources, eschewing both oral tradition (except to the degree that I am a grateful recipient of some of that oral tradition, which therefore informs my reading) and anthropological evidence. My aim, once again, is to provide an account of Buddhist ethics as it is explicitly represented in texts Buddhists take to be more or less canonical, and not to describe how actual Buddhists act or think about their own moral lives. This is reasonable: when discussing Western ethical theory, we do the same thing. I have tried to draw on a wide variety of Buddhist voices, principally from India and from Tibet.

I have given less attention to classical texts from East Asia or from Southeast Asia than to those from India and Tibet, simply because there is in those literatures less explicitly ethical reflection than we find in Indian and Tibetan literature, and what there is tends to follow Indian sources, not adding a great deal to what we find in the Indian and Tibetan literature. Given the fundamental role that Indian texts play in these traditions, and the fact that the literature in East Asia that does address ethical issues is largely devoted to glossing terminology, I do not think that this is a serious lacuna in my presentation, but it is a lacuna that must be acknowledged. There is more attention to East Asian and Southeast Asian contributions in the chapter on Engaged Buddhism, a movement in which scholars and activists from these regions have been central.

The fundamental idea that guides all Buddhist philosophy is pratītyasamutpāda, or dependent origination, the idea that every event or existent depends upon countless causes and conditions. As we will see in this book, that idea has not only metaphysical but moral implications. One of those is that reflection on the links of dependence that govern one’s own life generate gratitude. My own study of Buddhist philosophy—and of Buddhist ethics in particular—owes an enormous amount to a number of teachers and colleagues.

I first thank my monastic teachers and colleagues. Thanks to the ven Barry Kerzin, whose life and medical service beautifully exemplify the moral

cultivation at which Buddhism aims. Thanks to the ven Jampa Tsedroen, whose tireless work on the restoration of full ordination for Tibetan nuns brings Buddhist ethics so effectively into the modern world. I am grateful to Joan Halifax Roshi, whose straightforward teachings, caring hospice work, and medical efforts in Nepal so beautifully illustrate the brahmavihāras.

I thank the ven Geshe Namgyal Dadul, among the most articulate exponents of Buddhist teachings I know, and the ven Geshe Ngawang Samten, whose collaboration has so supported my own study of Buddhism. Thanks to the ven Thubten Chödron, who has brought the Tibetan monastic tradition to the United States and who has worked so hard to show contemporary people how to cultivate a Buddhist ethical practice. I thank the ven Tashi Tsering, superb teacher and crosser of cultures, and the ven Wangchuk Dorje Negi, whose good cheer and clarity of mind illuminate difficult issues. Finally, and most importantly, I express my deep gratitude to the ven Geshe Yeshes Thabkhas, who has taught me, and so many others with vast wisdom, grace, and generosity, and who never fails to point out the ethical implications of every letter of Buddhadharma.

I owe an enormous amount to colleagues in Buddhist Studies, conversations with whom over the years have contributed to my understanding. In particular I thank Daniel Aitken, Nalini Bhushan, José Cabezón, Sue Darlington, Thomas Doctor, Douglas Duckworth, Bronwyn Finnigan, Charles Goodman, Janet Gyatso, Stephen Harris, Richard Hayes, Maria Heim, Sara McClintock, Emily McRae, Susanne Mrozik, Andy Olendzki, John Powers, Graham Priest, Mark Siderits, Gareth Sparham, Christof Spitz, Birgit Stratmann, Sonam Thakchöe, Tom Tillemans, and Abraham Veléz. Maria Heim has been an invaluable interlocutor and colleague, constantly forcing me to broaden my vision, and illuminating so much of Buddhist moral psychology. I have learned a great deal from Andy Rotman, who has emphasized the importance of narrative to understanding Buddhist ethics, and from Charlie Hallisey, who has shown so many of us how to read these texts with care and openness. Steve Jenkins and Guy Newland have been close friends and colleagues for decades, and my views owe so much to our discussions and to the examples their lives have set that I can never thank them enough. I can only acknowledge that they are the source of much of what I think about these matters. I am also deeply grateful to the students in my seminar on Buddhist Ethics at the Harvard Divinity School in 2019 for valuable conversations from which I learned a great deal, reminding me once

again that one of the great gifts of teaching is the opportunity to learn from one’s students.

I have learned the most about Buddhist ethics from the writings and the examples of three truly great contemporary Buddhist ethicists: His Holiness the Dalai Lama XIV, the most ven Prof Samdhong Rinpoche, and the ven Thich Nhat Hanh. Nothing I could say could express my gratitude to these three giants of ethical theory and exemplars of ethical conduct.

I am not the first to write on this topic, and my own thought owes a great deal to the work of Martin Adam, Bhikkhu Anālayo, Bhikkhu Bodhi, Barbra Clayton, Sue Darlington, Charles Goodman, Christopher Gowans, Maria Heim, Damien Keown, Sallie King, Christopher Queen, and Abraham Veléz. Many of these scholars have addressed in greater depth issues I discuss here. While I do not agree with all of them on all matters, I have learned from each of them, and I recommend their work to my own readers. I hope only that this book adds something to the conversation to which they have each contributed so much. Sometimes a different perspective can move things along.

Special thanks to Amber Carpenter, Thomas Doctor, Douglas Duckworth, Janet Gyatso, Stephen Harris, Oren Hanner, Maria Heim, Steve Jenkins, Sallie King, Emily McRae, Susanne Mrozik, Geshe Dadul Namgyal, Guy Newland, Shaun Nichols, John Powers, Graham Priest, Cat Prueitt, Sonam Thakchöe, Christopher Queen, and Jan Westerhoff, and to an anonymous reader for their very careful readings of earlier drafts of this manuscript. Their incisive critique forced me to think harder about some of these issues, to be much clearer and to be more precise about some issues, and to change my mind about others. Each one of these extremely generous colleagues substantially improved the exposition. I have not taken all of these friends’ advice, and they should not be held responsible for the errors that remain.

Very special thanks to Maria Heim, who not only carefully retranslated all of the quoted passages from Buddhaghosa for me to ensure accuracy and fluency, but also drew my attention to how their context and technical vocabulary must be read in order to interpret them. I am enormously grateful for this extraordinary act of collegial generosity.

This work was made possible in part by a sabbatical leave from Smith College. I thank the college for that support. I also thank the Five College Buddhist Studies Program and the Philosophy Department at Smith College for providing a perfect working environment. I thank Kristina Liu, Riley

Mayes, Molly McPartlin, and Hallie Jane Richeson for useful editorial and research assistance.

Finally, I thank Ms. Avery Masters for her enormous contribution to this project as my principal research assistant. She worked tirelessly on this project, chasing references, and offered excellent advice on the organization of the volume, sound philosophical critique, and superb editorial support. Avery has become more of a colleague than an assistant. I could have never completed this book without her.

The Foundations of Buddhist Ethics

Buddhist ethics, as we will see in far more detail in subsequent chapters, constitutes a moral phenomenology grounded in core Buddhist doctrines concerning the nature of our life in the world and the existential problem the world poses for us.1 The most fundamental of these doctrines is pratītyasamutpāda, or dependent origination: the thesis that every phenomenon is dependent for its existence or occurrence on countless other phenomena in a vast web of interdependence. That web is multidimensional, comprising different kinds of causal relations as well as relations of mereological dependency, and dependency on human conventions and conceptual imputation.

Moral reflection must take all of these dimensions of dependence into account. The complexity of interdependence is one of the principal reasons for the untidiness of Buddhist moral discourse. As we will see in what follows, to focus merely on motivation, or on character, or on the action itself, or on its consequences for others, would be to ignore much that is important. We will also see, however, that the principal unifying strands in Buddhist moral philosophy—a focus on moral perception and experience as well as an emphasis on a path to moral cultivation and the transformation of character— arise from reflection on interdependence.

The doctrine of dependent origination is closely associated with a second core doctrine: anātman, or no-self: the idea that neither persons nor anything else have a core self or identity that makes us what, and who, we are; that we are nothing but an open set of causally linked psychophysical processes with a merely conventional identity. The boundary between self and

1 Damien Keown notes this fact when he writes at the beginning of his exposition of Buddhist ethics that the “invitation [the Buddha] extended to his followers was to participate in the highest and best form of human life, to live a ‘noble’ life This form of life embraces both seeing the world in the way the Buddha came to see it, and acting in it the way he acted” (1992, 1). While in the end Keown embraces an aretaic account of Buddhist ethics (as he notes on the next page of his book), it seems clear that he also understands its profoundly phenomenological character.

Buddhist Ethics. Jay L. Garfield, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2022.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190907631.003.0001

others is regarded as conventional and as inadequate to underwrite a special role of self-interest in prudential reasoning. While recognizing the importance of this distinction in our ordinary ethical thought and our need to recognize it in practical reasoning, many Buddhist ethical theorists argue that we assign too much importance to this boundary.2

Personal identity itself is, on a Buddhist view, a conventional matter. The relations between distinct stages of these continua are merely relations of causality and resemblance, not identity. The only actual identity we have is one that is imputed to us by ourselves and by others—a narrative, or conventional, identity. This identity, as we will see, is ethically significant, but it is constructed, not discovered.3 This is one of the reasons that, as we will see in Chapter 5, so much of Buddhist ethics is encoded in stories. The widespread use of narrative in Buddhist ethical literature also reflects the sense that moral reflection is part of the way that we make sense of ourselves and others, as characters in a jointly authored narrative.4

Moreover, causal chains are porous. Our personal stages are not only caused by, and do not only cause, other states regarded conventionally as internal to our continua; we are also, and must be, causally open to the world, including those with whom we associate, through links of perception, action, cooperation, group membership, and so forth. But inasmuch as these are the very relations that constitute our conventional identities, they suggest that those identities themselves are porous. Subjectivity and agency may be dispersed; our sense of individuality and distinctness from our environment is an illusion that masks both a thorough embeddedness and the incoherence of any independent existence—a situation that Thich Nhat Hanh (1987) has aptly called interbeing. As we will see, Buddhist moral thought takes this interbeing very seriously, as seriously as most Western philosophy takes individualism.

This grounding in the fact of thoroughgoing interdependence takes us to one important difference between Buddhist and most Western moral reflection. Many Western moral theorists begin by taking a kind of ontological and axiological individualism for granted in several respects. First, agency

2 But see Jenkins (2015) for an important cautionary note. Jenkins points out that many contemporary scholars, focusing too much on interdependence and the conventional character of identity, underestimate the importance of the distinction between self and other in Buddhist moral literature.

3 See Garfield (2015, 91–121; 2022) and Gowans (2015, 24–27) for more on this. Also see Parfit (1986) for an extended investigation of the relationship between the doctrine of no-self and ethics. Although Reasons and Persons is written entirely in conversation with Western sources, Parfit does note the affinities of his own view to those articulated in the Buddhist tradition (502–503).

4 Narrative, as we will see in Chapter 5, also allows us to express the particularity of moral situations, and to articulate the casuistic approach to moral reasoning that characterizes so much of Buddhist ethics.

is taken to reside in individual actors, with an attendant focus on moral responsibility, rights, and duties as the central domains of moral concern. Second, what is in one’s interest is taken to be, au fond, an individual matter; even when the self is consciously deconstructed, as it is by Parfit (1986), interest is taken by most Western theorists to attach to individual stages of selves. Third, and consequent on these orientations, a conflict between egoistic and altruistic interests and motivations is regarded in the West as at least prima facie rational, even if not morally defensible or ultimately rational. As a consequence, an important preoccupation of Western ethics is the response to egoism, an answer to the question, “why be good?,” a question which barely arises in a Buddhist context, and, when it does, is quickly answered with a burden of proof shift, as we will see in Chapter 9.5

For this reason, one important difference between Western and Buddhist approaches to morality is that agency is not taken as a primary moral category, at least when that term is understood to indicate a unique point of origin of action in an individual self. While Buddhists recognize that any action requires an agent, Buddhist moralists recognize no special category of agent causation that privileges that locus as a center of responsibility. Instead, action, intention, and results of actions and intentions are often seen as causally distributed. We will also see that interest is seen as a shared phenomenon. Therefore, we will see that in Buddhist ethics, moral progress and moral experience, rather than moral responsibility, are foregrounded in moral reflection. Moreover, that progress and experience are not the progress and experience of a substantial or continuing self, but rather of the kind of open continuum of psychophysical processes we call a person. We will work out the ramifications of these views as we proceed.

All of Buddhist philosophy, including all of Buddhist ethics, is grounded in the “four noble truths” set out in the Buddha’s first public teaching at Sarnath, The Discourse Turning the Wheel of Dharma (Dhammachakkapavatannasutta). The four noble truths encapsulate the existential situation that Buddhism addresses. The first of these truths is that all of life is permeated by suffering (dukkha). Second, suffering has a cause. This idea is articulated in later Buddhist literature as the thesis that suffering is caused by

5 A bit of nuance is needed here. This is not to say that the question never arises for anybody who identifies as a Buddhist. Obviously, Buddhists, like anyone else, sometimes ask themselves why moral concerns should trump egoistic concerns in certain contexts, and Buddhist teachers like moral educators anywhere, often have to give people reasons to attend to ethical considerations. The point here is that Buddhist moral theorists never take this to be an issue: egoism gets no purchase in this tradition as a prima facie rational option.

attraction and aversion grounded in primal confusion about the nature of reality. Third, since suffering has a cause, the removal of that cause can alleviate it. And fourth, the eightfold path of Buddhist practice is the vehicle for that alleviation. Nāgārjuna (ca. 2nd century CE), the forefather of the Madhyamaka tradition of Buddhist philosophy, and arguably the most important of all Mahāyāna philosophers, argues persuasively in his major treatise, Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way that to understand dependent origination is to understand these four noble truths.6 It is therefore appropriate to begin our exploration of Buddhist ethics with the four noble truths. We will address these truths in detail in Chapter 6, but a brief introduction here will be helpful.

The first truth—that of the ubiquity of suffering—sets the problem that Buddhism proposes to solve. The universe is pervaded by suffering and the causes of suffering. The Buddha did not set out to prove this at Sarnath. He took it as a datum, one that is obvious to anyone on serious reflection, though one that escapes most of us most of the time precisely because of our evasion of serious reflection in order not to face this fact. The Buddha also assumed that suffering is a bad thing, even when one does not know that one is suffering, and even when one experiences suffering as pleasure.

If one disagrees with this assessment, Buddhist moral discourse has no basis. There would be no problem to be solved. If you just love headaches, don’t bother taking aspirin. If you don’t like them, you might consider how to obtain relief. Similarly, if the world and your life are really fine, Buddhism may not have much to say to you; but if life and your own comportment to it seem to be less than ideal, Buddhist ethicists think that it might make sense to pay attention to what they have to say. Buddhist reflection on the nature of suffering gives us reason to think that, in fact, all of our lives are less than ideal; we each, whether we are immediately aware of it or not, confront the problem of the ubiquity of suffering. We therefore each confront this existential problem. For this reason, Buddhist ethical reflection and practice are fundamentally problem-solving enterprises, beginning with the presumption that life is unsatisfactory, and aimed at making ourselves, and the lives we lead, more satisfactory.

The Buddha then argued that suffering does not just happen. It arises as a consequence of actions conditioned by attachment and aversion, each of which in turn is engendered by primal confusion regarding the nature of reality. As the Discourse on the Correct View (Sammaditthi sutta) puts it, “And

6

what is the root of the unwholesome? Attraction is a root of the unwholesome; aversion is a root of the unwholesome; primal confusion is a root of the unwholesome.”

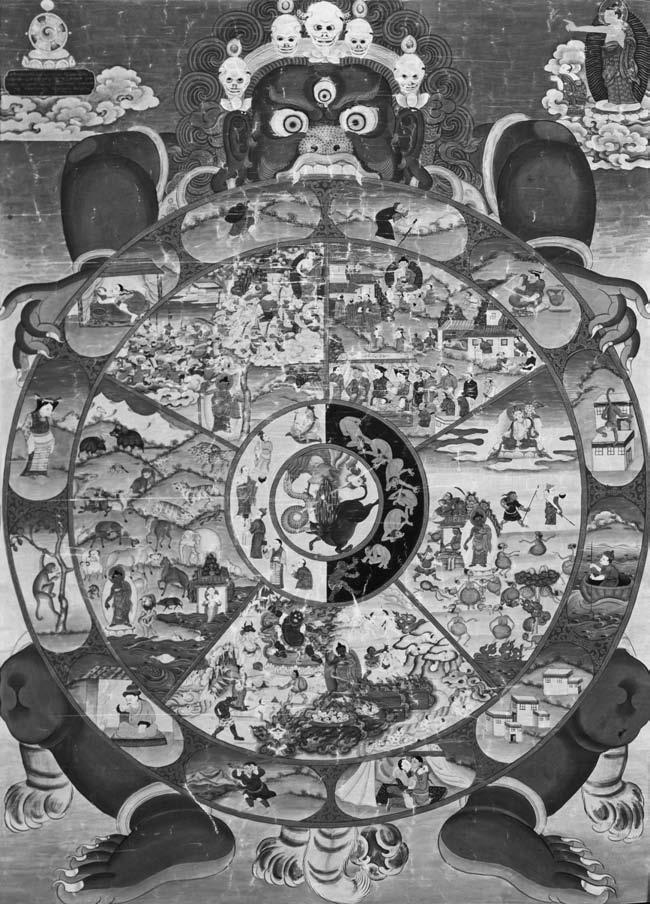

This triune root of suffering is represented in the familiar Buddhist representation of the Wheel of Life (Bhavacakra).7 We find the pig, the snake, and the rooster at the hub representing confusion, aversion, and attraction, respectively. The six realms of transmigration—hell, hungry spirits, animals, martial demi-gods, divine beings, and humanity—turn around them. The entire process is structured by the 12 links of dependent origination that represent, depending on the context of interpretation, either the psychological processes that govern perception, conation and action, or the process of life and rebirth.8

These six realms can also be read less cosmologically as representing aspects of the phenomenology of everyday suffering, what Freud was to call “the psychopathology of everyday life.” While most Buddhist religious traditions, and most of those who identify as Buddhist, regard these as literal loci of rebirth for sentient beings, they can also be read—as they are in some modern Buddhist communities, particularly in cultures that reject literal rebirth—and even by some Indian and Tibetan scholars who are committed to a strong doctrine of rebirth, such as the 19th-century Tibetan scholar Patrul Rinpoche—metaphorically as denoting affective sets, or moods.

Here is how we might do so: The hell realm is that state we are in when everything seems just terrible, and each thing we encounter is yet another torture, eliciting anger and hostility as dominant emotional reactions. The realm

7 The Bhavacakra, despite the fact that it most widely associated with Tibetan Buddhism today, is an icon with classical Indian origins, and was painted at the entrance to most Indian Buddhist temples, as it is in Tibetan temples today.

8 It is important to bear in mind that even the most traditional and literal Buddhist readings of rebirth are very different from orthodox Indian doctrines of reincarnation. The orthodox view is that there is a soul (ātman) that persists through biological life, survives biological death, and is united with a new body in a subsequent life. This eternal self is the bearer of karma. Buddhists, however, reject the idea that there is an ātman. In fact, this rejection is one of the central tenets of Buddhist metaphysics. Instead, persons are regarded as causal continua of psychophysical processes with no underlying self. We are, on this view, neither numerically identical to our previous nor to our subsequent stages, even within a biological life. So, on its most literal, or traditional reading, the Buddhist doctrine of rebirth is the view that there are causal connections between some continua in successive biological lives that are analogous to those obtaining between stages of a single life.

On a more liberal reading, we can simply to take this to be doctrine that there are causal connections between continua of previous lives, continua in the present life, and those in future lives. Note that this claim is pretty obviously true, and it is metaphysically pretty weak. But it is enough to direct our moral attention to our responsibilities inherited from the past and to our responsibilities to those who will follow us. This weaker understanding of rebirth is arguably at work in much of East Asian Buddhism, and is also increasingly popular among contemporary Buddhists, particularly in the Western and East Asian worlds, while the more traditional version, with its commitments to particular causal chains between individual psychophysical continua, is more prevalent in Indian, Tibetan, and Southeast Asian Buddhist communities. Geshe Lhundup Sopa (1984) presents a careful reading of the iconography of the Bhavacakra emphasizing its multiple readings.

of hungry spirits represents those times when we feel insatiably and pathologically needy, and nothing we have feels like enough. The animal realm is that state in which we snap reactively at others, responding to first impressions, without any insight or reflective understanding, behaving in a way we might call beastly. The realm of the asuras (this one is hard to translate; they are represented as superhuman, quasi-divine beings whose lives are dedicated to

martial struggle with one another for power and glory) represents those times when we covet honor and attention, and when we are filled with envy for those who received honor and attention. The divine realm captures those moments when we think that we are in paradise, and that it will go on forever, heedless of the suffering of others and what will come next for us. (As the Indigo Girls sing in Perfect World, “I’m OK if I don’t look a little closer.”)

Finally, the human realm represents those moments when, although beset by the normal sources of suffering, and afflicted by psychopathology, we manage to be humane, or responsive to one another. It also represents the situation in which we are both aware enough of the unsatisfactory nature or our lives to be motivated to change, and smart enough to be able to effect meaningful change. That is, we are not so overcome by pleasure—as in a heavenly state—that we have no motivation to act. Nor are we so overcome by suffering—as in a hellish state—that we have no hope. Instead, as human beings, we find ourselves in a state of psychological and affective complexity. While this human existence is unsatisfactory, in virtue of being governed by confusion, attachment, and aversion—and hence permeated with suffering— it provides the opportunities we need for improvement. 9 A careful reading of texts such as Śāntideva’s How to Lead an Awakened Life (Bodhicāryāvatāra), which focuses so sharply on the psychology of virtue and vice, suggests that this metaphorical reading might have been familiar classically as well.10

All of this is, in turn depicted as resting in the jaws of death, the great fear of which propels so much of our maladaptive psychology and moral failure.11 Āryadeva (ca. 3d–4th century CE), at the very beginning of his 400 Verses (Catuhśataka), notes the power of this fear, and its connection to denial:

3. You see the past as brief Yet see the future differently. To think both equal or unequal Is clearly like a cry of fear. (1994, trans. R. Sonam)12

9 This is on the psychological reading. On the cosmological reading of the icon, the human realm is favorable simply because a human body and mind afford the greatest opportunity for moral development and progress toward awakening. It is the realm in which the awareness of suffering coexists with sufficient skill and intelligence to do something about it.

10 So, for instance when Nāgārjuna in Precious Garland, 228–229, says that desire makes one a hungry ghost, that hatred sends one to hell, and obscuration to an animal state, this has an obvious and plausible psychological reading. And when he then says that eliminating these three pathologies leads to a human or divine state, that statement has the ring of a psychological claim as well.

11 See Becker (1986) for a detailed discussion of the pervasive impact of the suppressed fear of death on human psychology and behavior.

12 Many Indian Buddhist texts are written in verse. When that is the case, I represent them in the four-line form common to that genre, indicating the verse number within the chapter.

Āryadeva’s point is straightforward: we act as though our future is surely longer than our past, even though we know that this may not—or for some of us, is surely not—the case. When we act this way, we do so only to allay the fact that we know that this may well not be so, and to manage our fear of death. A bit later, Āryadeva explicitly argues that only the acceptance of the inevitability of death can allay this fear and liberate us from its pernicious consequences:

25. Whoever with certainty has The thought, “I am going to die,” Having completely relinquished attachment, How could they fear even the Lord of Death? (1994, trans. R. Sonam)

A contemporary Tibetan philosopher, Geshe Sonam Rinchen, comments on these verses and the pathology to which they point as follows:

Though none of us think we will live forever, we act as if certain we will not die today, tomorrow, next month, or next year. In fact our hopes and plans are based on the assumption that we will live for a long time. We plan to secure our livelihood, possessions, wealth, friends, and status. Our pursuit and acquisition of these things involves craving and attachment. Inevitably, therefore, hostility arises towards anyone or anything that could deprive us of what we seek or damage what is ours. Unaware of the destructiveness of attachment and anger, we create much harm which causes us trouble in this life and destroys our chances of happiness in future lives. Thus the possibility of attaining liberation, or even good rebirths, grows more remote.

Cultivating an awareness of death’s closeness is a great benefit. (1994, 81)13

Whether we take this cosmologically—as Geshe Sonam Rinchen does—or psychologically, the point is that the simultaneous pervasive awareness of our mortality and the repression of that awareness sends us into a cycle of confusion about our nature, attraction, and aversion that in turn propels us

13 Here we might note the affinities of much Buddhist thinking about the importance of the awareness of death to Stoic and Epicurean thought. Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations constitutes a particularly useful resource. See, for instance, 2.12, 2.14, 3.1, 3.10, .48, 5.33, among other relevant passages (Marcus Aurelius 1983).

from one moral mood to another.14 To gain control of our moral psychology requires a confrontation with that fear and an overcoming of it.15 All of these ideas are packed into the terse formulation of the second noble truth. They are uncovered in the commentarial literature, even if they are not explicitly present in the sutta itself.

Attention to that truth allows us to see another sense in which Buddhist moral thought is very different from most Western moral thought: the three roots of suffering are each regarded as moral failings or pathologies, and they are not seen as especially heterogeneous in character. None of them, however, are seen as particularly problematic in most Western moral theory, and indeed each of the first two—attachment and aversion—is valorized in at least some contexts in some systems, particularly that of Aristotle. The third—confusion—is rarely seen in the West as a moral matter, unless it is because one has a duty to be clear about things, as in the culpable ignorance of a physician or an airline pilot.

But things look different from the perspective of Buddhist moral theory. We must bear in mind that the Buddhist soteriological program—and therefore its ethical perspective—is entirely motivated by the first and second truths. It is hence at bottom not a system of abstract speculation about the nature of reality, but an attempt to solve an existential problem. The three root vices of attraction, aversion, and confusion are vices because they engender that problem. The moral theory here is not meant to articulate a set of imperatives, nor to establish a calculus of utility through which to assess actions, nor to assign responsibility, praise or blame, but rather to solve a problem. The problem is that the world is pervaded by unwanted suffering. The diagnosis of the cause of the problem sets the agenda for its solution.16

The third truth articulated by the Buddha at Sarnath is that, because suffering depends upon confusion, attraction, and aversion, it can be eliminated by eradicating these causes. This also grounds an important difference between Buddhist and most Western approaches to ethics. Buddhist ethics, we will see, is concerned primarily not with how we act in the world, but with how we see the world in which we act: actions are important, but secondary, flowing from moral vision. Buddhist ethical practice is therefore devoted to

14 While I think that in order to see Buddhist ethics as a useful resource for contemporary philosophy the psychological reading of the image is more useful, some argue that this seriously distorts the understanding of canonical Buddhist doctrine, and underestimates the centrality of cosmological thought, as well as of the role of rebirth in understanding karma in Buddhist moral theory. See Gethin (1997, c. 5) for a clear articulation of this position.

15 See Nhat Hanh (2003, 2017) for excellent discussions of the importance of cultivating mindfulness of death in moral development.

16 Also see Garfield (2015, 9–11) and Gowans (2015, 107–109) for a discussion of the second truth.

cultivating a more salutary ethical perception of the world, and one that is more salutary because it is less deluded. The cultivation of wisdom is hence at the heart of ethical development.17

The fourth truth, which starts getting the ethics spelled out in a more determinate form, presents the path to that solution. The eightfold path is central to an articulation of the moral domain as it is seen in Buddhist theory, and careful attention to the path reveals additional respects in which Buddhists develop ethics in a different way than do Western moral theorists. The eightfold path comprises correct view, correct intention, correct speech, correct conduct, correct livelihood, correct effort, correct mindfulness, and correct meditation. It is erroneous when reading this list to think of it as sequential, that is, to think that first one cultivates right view, then right intention, then right speech, and so on. Instead, the path denotes a set of areas of concern, domains of ethical comportment and cultivation that are mutually interdependent: each supports all of the others.18

While many Buddhist philosophers—canonical and contemporary— following the traditional Buddhist classification of three trainings (proper conduct, concentration, and wisdom) focus specifically on correct speech, action, and livelihood as the specifically ethical content of the path (e.g., Gowans 2015, 22–24), this is in fact too narrow, and misses the role of the path in Buddhist practice and in the overall moral framework through which Buddhism recommends engagement with the world. It may also result from an unfortunate translation of the Sanskrit term śīla that covers speech, action, and livelihood in this context as ethics. Proper conduct is better.19 The eightfold path identifies not a set of rights or duties, nor a set of virtues, but of dimensions of conduct.20 The path indicates the complexity of human moral life and the

17 In this respect, there are interesting affinities to Stoic ethics. See Gowans (2003, c. 4; 2015, 188), Cooper and James (2005, c. 4), McEvilley (2002), Kuzminksy (2008), and Carpenter (2014, 31–32; 60). Also see McRae (2018b), who argues that Buddhist accounts of detachment are distinct from Stoic accounts in that they not only connect detachment to the abatement of pathology, but to the enhancement of positive affective attitudes, such as love and care, in virtue of the connection of these attitudes to the abandonment of the egocentricity that Buddhist moral theorists see as the heart of psychopathological emotional states, and the cultivation of the nonegocentric attitudes that enable positive affective attitudes toward others. There are also important parallels between this aspect of Buddhist ethics and the approach of Scottish sentimentalists such as Hume and Smith, who were inspired by the Stoics.

18 See Bhikkhu Bodhi (2006) and Heim (2020) for a more detailed discussion of the eightfold path.

19 See Cowherds (2015, 12) and Heim (2020, 18–23) for discussion of the semantic range of śīla Note that Keown describes his entire enterprise in (2002) as an enquiry “into the meaning of śīla and its role in the scheme of the eightfold path” (2), It is also worth noting that, as Ives (2018) points out, the rubric of the three trainings is used to subordinate ethical cultivation to the achievement of meditative skill and wisdom, with ethical cultivation seen only as instrumental to these practices aimed most directly at understanding the nature of reality.

20 Carpenter (2014, 11) agrees regarding the way to understand the eightfold path, and points out that only speech, conduct, and livelihood are directly connected to action; the majority of the path concerns the cultivation of salutary psychological states.

complexity of the sources of suffering. To lead a life conducive to the solution of the problem of suffering is to pay close heed to these many dimensions of conduct.

The eightfold path, which represents the earliest foundation of Buddhist ethical thought, must always be thought of as a path, and not as a set of prescriptions. And, as we will see in Chapter 7, this is only the first of many paths that populate the Buddhist moral world. Indeed, the metaphor of path (marga) is among the leading metaphors in Buddhist ethics. The eightfold path enumerates domains of life on which to reflect, respects in which one can improve one’s life, and in sum, a way of progressing cognitively, behaviorally, and affectively from a state in which one is bound by and causative of suffering to one in which one is immune from suffering and in which one’s thought, speech, and action tend to alleviate it.21

By following this path—by attending to these areas of concern in which our actions and thought determine the quality of life for ourselves and others—we achieve greater individual perfection, facilitate that achievement for those around us, and reduce suffering. There is no boundary drawn here that circumscribes the ethical dimensions of life; the account of the path is not grounded in any distinction between the obligatory, the permissible, and the forbidden; there is no distinction drawn between the moral and the prudential, between the public and the private, or between the self-regarding and the other-regarding. Instead, there is a broad indication of the complexity of the solution to the problem of suffering, and a suggestion that that task, while it takes us from a starting point to a goal, may indeed always be a work in progress. Indeed, Nāgārjuna distinguishes two levels of achievement on the path to moral maturity:

3. In one who first attains high status Definite goodness arises later, For having attained high status, One comes gradually to definite goodness.

4. High status is considered to be happiness. Definite goodness is liberation. (2007)

High status here traditionally refers to rebirth in the divine or human realm, or, more psychologically, the achievement of a pleasant, or humane

21 See Cowherds (2015, 80–84) for further discussion of the role of path in Buddhist ethics.

state of being. That is worth achieving, and it is an important goal of ethical practice. But the vision behind the iconography of the wheel of life suggests that even this is not entirely satisfactory: the ultimate goal is liberation from the entire round of rebirth. Again, if we read this in a psychological as opposed to a cosmological register, this is the idea that even when we are at what seems to be our best, we are subject to primal fear and anxiety, and that means that at any moment we can be propelled to a less morally and hedonically salutary mood. Anger or unhappiness can arise even on the beach, or while volunteering in the soup kitchen, or while sitting in meditation!

So, since fear is the great driver of pathology, the ultimate goal of moral practice must be a kind of freedom from that fear, and from the confusion, attraction, and aversion it conditions; that is, it constitutes a revolution in our moral psychology that allows us to experience the world in a way so different from our natural experience that we cannot even possibly fall into adverse moral moods. This enables an important kind of freedom: not the absolute freedom envisioned by advocates of a free will, but freedom from being caused by pathologies with which we do not identify to move arbitrarily from mood to mood. This issues in a degree of control over our affective set, control which can be understood in terms of the causation of our emotions and actions by motivations and attitudes with which we can identify. It is this profound transformation at which Buddhist practice is aimed, and which Buddhist ethical theory aims to characterize.22

The term karma plays a central role in any Buddhist moral discussion. It is a term of great semantic complexity and must be handled with care, particularly given its intrusion into English with a new range of central meanings. Most centrally, karma means action. Derivatively (as a contraction of karmaphala, the effect of action), it means the consequences of action. Given the Buddhist commitment to the universality of dependent origination, all experience and action is inflected by the consequences of past actions, and all action has consequences.

22 For a more detailed discussion of the high status/definite goodness distinction and its role in Nāgārjuna’s ethical theory, see Amber Carpenter’s analysis in (2015, 6–8) and in Cowherds (2015, 21–42).

Karma is not a cosmic bank account on this view, or a system of reward and punishment, but rather comprises the natural causal sequelae of actions. Any action has consequences, simply in virtue of interdependence, and karmic consequences include those for oneself and for others, as well as both individual and collective karma. And karma has both a natural and a moral valence. Its natural valence derives from the fact that it is regarded in Buddhist traditions as purely causal. We will return to this point in Chapter 11. Its moral valence reflects commitment to the thesis (possibly false, but integral to the tradition) that karma works in such a way that morally positive actions have positive results, and morally negative actions have negative results (whether conceived in terms of rebirth or in terms of results in a single lifetime). Nāgārjuna puts it like this in the Precious Garland:

14. A short life comes through killing; Much suffering comes through harming; Poor resources through stealing; Enemies through adultery.

15. From lying arises slander; From divisiveness a parting of friends; From harshness, hearing the unpleasant; From senselessness, one’s speech is not respected.

16. Covetousness destroys one’s wishes; Harmful intent yields fright; Wrong views lead to error; And drink to confusion of the mind.

17. Through not giving comes poverty; Through wrong livelihood, deception; Through arrogance a bad lineage; Through jealousy, little beauty. (2007)

One might question some of the generalizations, but many are reasonable. The point though, is not whether they are each correct, but that Nāgārjuna takes the outcomes he notes to be the natural consequences of the kinds of actions from which they follow. Murderers are not known for their longevity, at least statistically speaking; nor are they revered after their passing. Those

who harm others often suffer unfortunate consequences. Theft is, in general, a lousy get-rich-quick scheme; adultery is not a great way to make friends, etc. This is what karma looks like from a naturalized Buddhist perspective.

It is important to see that karma isn’t regarded as additive or subtractive. There is no calculus of utility or of merit points here. The fact that something I do is beneficial does not cancel the fact that something else I do is harmful. It just means that I have done something good and something harmful. I have generated both kinds of consequences, not achieved some neutral state. No amount of restitution I pay for destroying the garden you worked so hard to cultivate takes away the damage I have done. It only provides you with some benefit as well. Truth and reconciliation commissions do indeed reveal the truth and promote reconciliation, and that is good. But to pretend that they thereby erase the horrific consequences of the deeds they reveal for those who are reconciled is naïve.

Note as well that the relevant kinds of karma include not only the impact of my actions on others, but also the impact on my own character, such as the tendency to reinforce or to undermine generosity or malice and the degree to which the action promotes general well-being. There is hence attention both to virtue and to consequence here, and attention to the character of and consequences for anyone affected by the action. But neither of these are fundamental dimensions of assessment, as they would be in aretaic or consequentialist systems. The facts relevant to moral assessment from a Buddhist perspective are progress or lack thereof on a path to the understanding of reality and the alleviation of suffering.23

Buddhist moral assessment and reasoning hence explicitly take into account a number of dimensions of action. We do not in this framework ask whether a particular action is good or evil simpliciter, nor do we ask what our obligations or permissions are. Instead, we ask about the states of character reflected by and consequent upon our intentions, our words, our motor acts, and their consequences. We ask about the beneficial and harmful consequences to which they give rise, and about how actions reflect and enhance or ignore and undermine our moral vision. But in doing so, we do not take these facts as basic; instead, we ask how these actions are relevant to solving our collective problem—the omnipresence of suffering—and

23 For a more detailed account of karma, very much consistent with my own, but linking it directly to Buddhist ideas about rebirth and to the attainment of nirvana, see Gowans (2015, 13–18, 76–91). Also see Carpenter (2014, 93–116) for a detailed discussion of the doctrine of karma in Buddhist philosophy more broadly, and its connection to other issues in Buddhist philosophy.

how they are relevant to our moral progress toward a state of awakening that permits us to act spontaneously in beneficial rather than in harmful ways.

For this reason, while this study of Buddhist ethics will lead to some general conclusions, it will also lead to a lot of what might appear to be disconnected observations about moral life. I will develop more a collage than a portrait of the ethical domain as it appears from the perspective of the Buddhist philosophical world. Buddhists have defended an enormous variety of positions on just about every philosophical question, and ethics is no exception. We will therefore encounter plenty of variety, including narratives from the Jātaka stories (tales of the Buddha’s former lives), from the Vinaya literature (treatises on monastic discipline), and the Therīgāthā (early literature by Buddhist nuns), as well as advice on governance, discussions of the Buddhist path, and even some more explicitly ethical treatises, concluding with some contemporary work on Engaged Buddhism. Not all of this will fit together neatly, but the lack of fit will reflect that Buddhists take moral reflection to be a complex matter, integrating a multiplicity of perspectives and considerations, rather than real doctrinal conflict. Taking this literature as a whole will give us as good sense of the moral domain as Buddhists see it. While I will not pretend to an exhaustive survey of this vast domain, I will try to give some sense of its diversity.24

Attention to this approach to moral assessment and to moral reasoning reveals that in this framework there is no morally significant distinction between self-regarding and other-regarding actions. All actions, from this perspective, affect both self and others. By improving myself morally, I benefit those around me; by benefiting others, I become a better person.25 Nor is there any distinction between moral and prudential motivations. Motivations that appear to be immoral but prudential are, on deeper analysis, simply confused; any benefit they may confer in the short term will be outweighed by the damage they cause not only to others, but to the actor as well. Nor is there any limit to the domain of the ethical. As long as we inhabit the ordinary world, karma is ubiquitous; interdependence is endless. Responsibility, as the Dalai Lama XIV constantly reminds, can only be universal (Dalai Lama 1999).

24 To get a good sense of the diversity within the tradition see the essays in Cozort and Shields (2018).

25 See Jenkins (2 015).

It is tempting to portray Buddhist ethical thought as constituting some grand system resembling those that populate Western metaethics. As I have already indicated, this is a dangerous prejudice to be avoided. On the one hand, we find in Buddhist philosophical and religious literature many texts that address moral topics, and a great deal of attention devoted to accounts of virtuous and vicious actions, of virtuous and vicious states of character, and of virtuous and vicious lives. On the other hand, we find very little direct attention to the articulation of sets of principles that determine which actions, states of character or motives are virtuous or vicious, and no articulation of universal sets of obligations or rights.1 Buddhist moral philosophers simply eschew the project of systematic metaethics. We do better when we try not to bring a Western ethical template to our reading of Buddhist ethics, and to take the tradition on its own terms.2

This has not stopped others from doing so. There seems to be an irresistible temptation to assimilate Buddhist ethics to some system of Western ethics, usually either some form of consequentialism (Goodman 2009, Siderits 2016) or some form of virtue ethics (Keown 1992).3 Those who read Buddhist ethics as utilitarian focus on the importance of suffering and its elimination, and on accounts of karma, reading these as suggesting that only

1 Although we certainly find lots of rules covering monastic discipline in Vinaya texts, as we will see in Chapter 10, these are defeasible, and are particular to those who adopt specific vows; they are not the assertion of universal duties.

2 See Gowans (2015, 54–57) for further discussion of the reasons for so little explicit systematic ethics in the Buddhist tradition, and on pluralistic interpretations (Gowans 2015, 155).

3 Gowans (2015) offers clear critical overviews of the principal motivations of and difficulties with deontological approaches (122–129); consequentialist approaches (129–138); and aretaic approaches (138–146) of Buddhist ethics. Goodman (2009) and Mark Siderits (2016) have argued that Buddhist ethics is a form of consequentialism. I address their arguments in Garfield (2010/2011) and in Garfield (2014). See also Cowherds (2015, 10, 141–158) for more discussion of the question of consequentialism in Buddhist ethics, and Keown (2002, 17–18, and c 7) for a critique of utilitarian readings of Buddhist ethics, and Keown (2002, c. 8), for an extended defense of an aretaic reading of Buddhist ethics.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190907631.003.0002

the consequences of our actions matter for moral assessment. We will see in what follows that this gets only at certain surface ideas in Buddhist ethics and fails to capture the structure of Buddhist moral thought. Those who focus on virtue note the perfections enumerated on the bodhisattva path and the brahmavihāras, or divine states of character (to be discussed in Chapter 9), each of which is central to Buddhist ethics. Once again, as we will see, this captures only part of the picture, and not the most fundamental aspect. Buddhist moral theory is neither purely consequentialist, nor purely aretaic, nor deontological. As Gowans (2014, 147–165) and I (2010/2011, 2012a) each note, each kind of evaluation is present, but there is no overarching concern for a unified form of moral assessment. Since the problem of suffering is complex, its roots are complex, and so its solution can be expected to be complex. Suffering is both caused and constituted by fundamental states of character, including preeminently egocentric attraction, egocentric aversion, and confusion regarding the nature of reality. Hence the cultivation of virtues that undermine these vices is morally desirable. Suffering is perpetuated by our intentions, acts, and their consequences. Hence attention to all of these is necessary for its eradication. Our own happiness and suffering are intimately bound up with that of others. Hence, we are responsible for others, and it is only rational to take their interests into account. Moral progress often involves undertaking precepts that govern our actions, and so sometimes we find our actions determined by duties.4

The absence of an overarching metaethical theory in Buddhist literature is not because Buddhist moral theorists were and are not sufficiently sophisticated to think about moral principles or about the structure of ethical life, and certainly not because Buddhist theorists think that ethics is not important. We will see as we explore the world of Buddhist ethics that this is instead because from a Buddhist perspective there are simply too many dimensions of moral life and moral assessment to admit a clean moral theory. The web of dependent origination is complex, and there is a lot to be said. So Buddhists have had a lot to say. But the web is also untidy, and so what Buddhists have had to say resists easy systematization.

This is not to say that Buddhist ethics is simply an amalgamation of Aristotle, Mill, and Kant into an incoherent jumble. Instead, Buddhist

4 Siderits discusses the question of whether we can even talk about Buddhist “ethical theory” given its heterogeneous structure and multiple concerns in Cowherds (2015, 119–139). See also Heim (2020, 2–4) for a discussion of this issue.