THE FILM DISPATCH

Issue seven: MeMORY MaRch 2023

chief editors

Flora Stokes

Yasmeena Sulaiman editors

Muyuan Wu

Yuqi Wang

Yiwen Shi

Rhys Monaghan

Ethan Radus

magazine design

Rhys Monaghan

graphic design team

Rhys Monaghan

Ronglian Xu

social media Team

Ronglian Xu

Ivy

website manager

Mengyan Gao

proof-reader

Lauren Chalker

memory page 2

/

email thefilmdspatch2023@ gmail.com social media @the_film_dispatch

THE FILM DISPATCH dedicated to the moving image

the teaM

Enys Men (2022): A Slice of Land Film

the FILM dIspatch / page 3 contents Introduction: Memory The Chief Editors

Yesterday (1991) Katherine

Only

Heller

Monaghan

Red

Michaela Flaherty Chungking Express (1994) Wifak Gueddana After life: The significance of memories to someone experiencing grief Aisling McDonagh How the 2023 BAFTAs Gave Me a Reason to Actually Watch the Oscars This Year Yasmeena Sulaiman A Memory of Dialogue Weiyi Wang Imagining Nothing: Memory in Oldboy (2003) Ethan Radus Remembering Avatar’s impact in light of Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) Flora Stokes Re-membering the Other: Mnemonic Sutures in Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959) Lim Kai Tjoon Fuori Programma Irene Ros Remembering Old Hollywood: Memory in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) Grace LaNasa Memories of Movie Watching Lesley Finn ............................................................................................... 4 ................................................................................................ 6 .................................................................. 8 ................................................................................................... 12 ....................................................................................... 14 ....................................................................................................... 18 ....................................................................................................... 22 ............................................................................................... 26 .................................................. 28 ............................................................................................................ 34 ............................................................................................................ 38 ..................................................................................................... 46 ...................................................................................................... 54 ................................................................................. 60

Rhys

Turning

(2022)

MeMory

By The Chief Editors

We proudly present the seventh issue of The Film Dispatch magazine. The theme we have chosen is “Memory”. We believe that cinema, and its reliance on signs and signification, lends itself to the artistic representation of memory through its visual form. Time and again, the thematic relevance of memory, nostalgia and reminiscence are shown to be key concerns of filmmakers across generations. Films considered by many to be the greatest cinematic works of all time pivot on humanity’s complicated relationship with the often unreliable nature of recollection, such as Orwell’s Citizen Kane (1941) or Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950). The intrinsically psychological and emotional contexts that inform the memory formation process have

cultivated films that stretch across various genres, forms and continents, some of which have been spotlighted in the thirteen articles we havecompiled.

This issue consists of a wonderfully varied selection of short pieces, reviews, and features, and our writers have approached the theme from wildly different angles. From authors revelling in the nostalgia of their own experiences at the theatre, to indepth analyses of character-driven, feature-length films such as Oldboy (2003) or Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959). Some of our writers have gone beyond fictional depictions, such as PhD student Irene Ros who discusses her own short film Fuori Programma,

memory page 4 /

which examines the collective memory of Italian right-wing political violence. We are delighted with the breadth of writing featured in this issue, and we would like to express our thanks to all those who contributed.

Thank you also to our proofreader and team of editors that have worked tenaciously to compile this issue. We also want to thank our social media team and web designers for their contributions and support. Your passion and dedication do not go unnoticed. Please enjoy these pieces from our incredible writers, and appreciate this trip down memory lane…

Your Chief Editors, Flora & Yasmeena

the FILM dIspatch / page 5

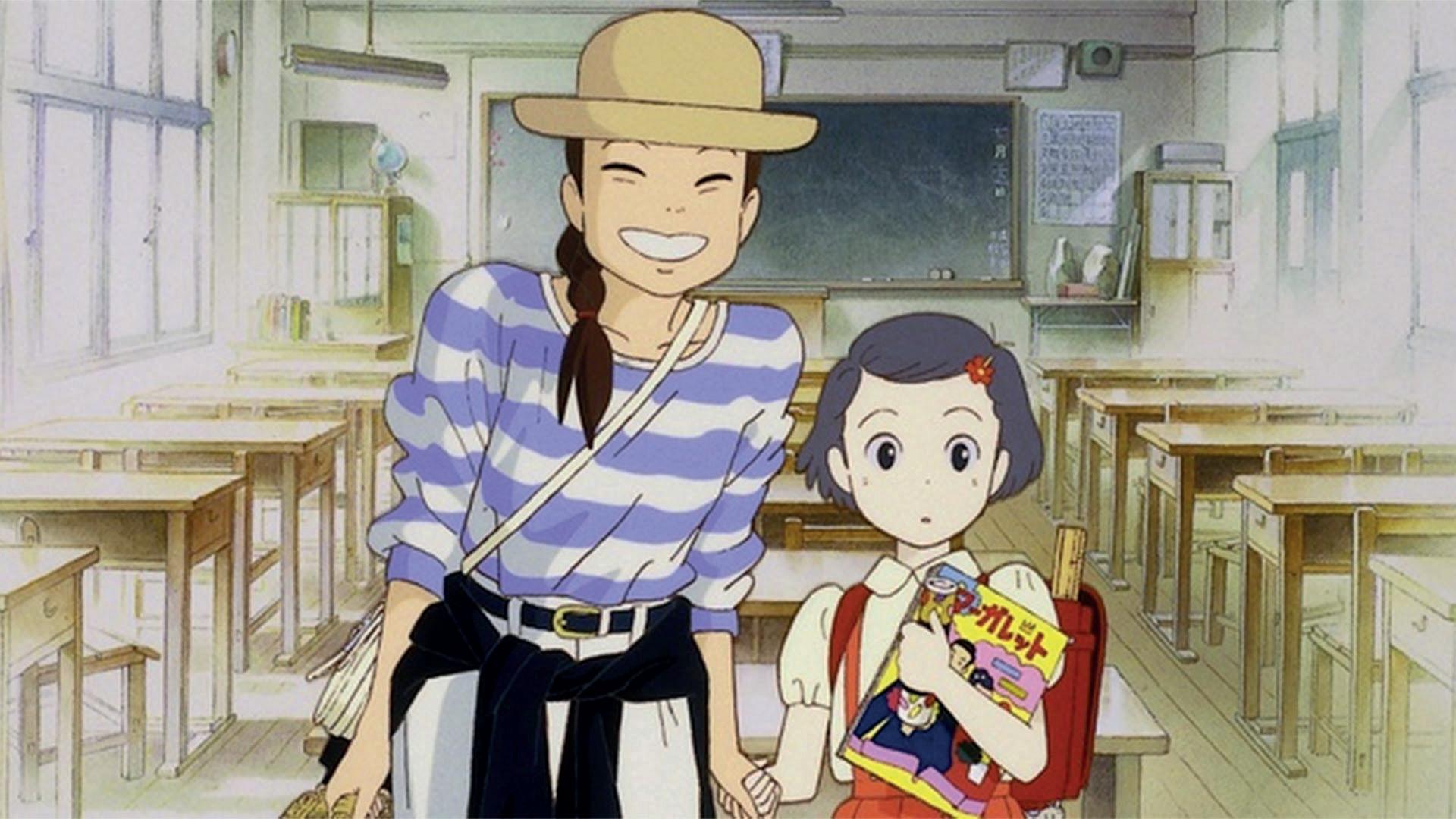

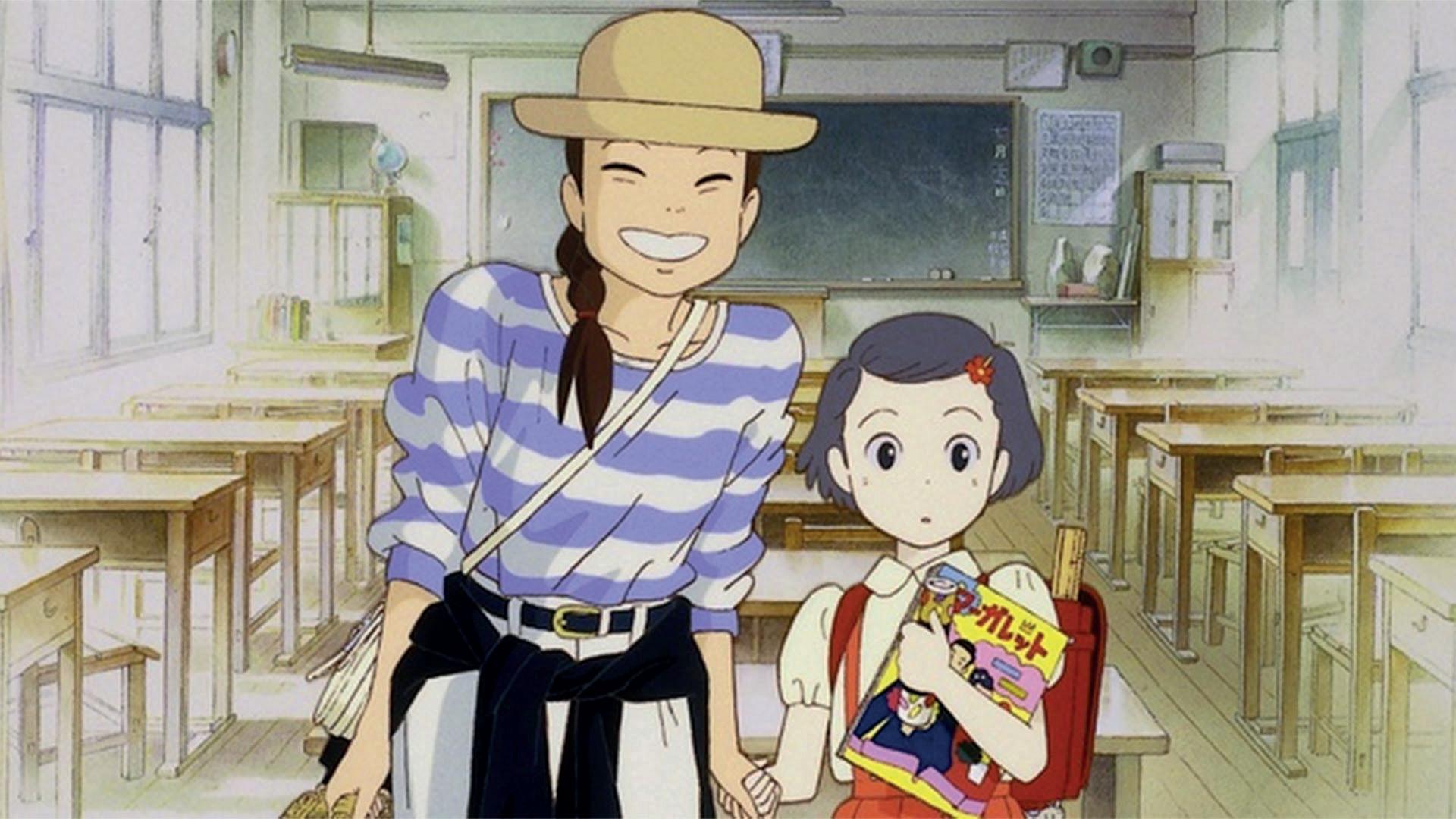

onLy yesterday (1991) revIew: a tIMeLess nostaLgIa

By Katherine Heller

Looking at Takahata Isao’s animated film Only Yesterday, Katherine Heller discusses its portrayal of childhood and nostalgia and how we can connect with one another through such memories.

There is something about animation that makes it the perfect medium for nostalgia and stories of reminiscence. Perhaps it is that, rather like the human memory, animation allows for an impression of life, rather than a complete reflection. One film that captures the dreamy yet raw quality of childhood memories perfectly is Takahata Isao’s 1991 film Only Yesterday, produced by the famed animation company Studio Ghibli.

For viewers familiar with Ghibli’s more fantastical output, such as Spirited Away (2001) and Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Only Yesterday may seem somewhat of an outlier; a down-to-earth tale of a young woman’s trip to the countryside and memories of her childhood. However,

this story of memory and identity is presented with such atmosphere that it encourages the viewer to dream just as much as any other Ghibli fantasy. Only Yesterday is based on a manga series that depicts the everyday life of a young girl named Taeko. Takahata uses memory and flashback as a framing device in his film adaptation. Our central character, Taeko, is shown to us as a 27-year-old unmarried woman, living and working in Tokyo. She decides to take a break from city life and go stay on the farm of her sisterin-law’s. During this trip she is overcome with memories of her life at age 10, in 1966.

Taeko is the youngest child in her family, and notes that her recollections of this time are very different to those of her two elder sisters. Her sisters’ memories of 1966 revolve around pop culture: listening to The Beatles and wearing miniskirts. Taeko’s memories centre on the everyday – friendships, first crushes, puberty, schoolwork and family tensions. I find that my memories of life at age 10 (al-

memory page 6 /

though this was in 2006 rather than 1966) are much the same. Only Yesterday’s portrayal of Taeko’s memories – often in a relatively muted pastel palette, with a poignant score by Hoshi Katsu – is almost exactly how I would imagine an audiovisual representation of my own memories.

In addition to its realistic portrayal of bittersweet nostalgia, I can also attest somewhat to the accuracy of the period detail. One of Taeko’s memories is of the day that her father brought home a pineapple. No one in the family had ever seen a real pineapple before. They aren’t sure how to slice it, so put it aside. Taeko’s eldest sister, Nanako, comes home the next day having found out how to eat this exciting fruit! They slice and eat the

fruit, not knowing that it is still unripe. The whole family is disappointed and the middle sister, Yaeko, even expresses that tinned pineapples are much nicer. My father, born in 1960, finds this scene greatly entertaining, recalling similar excitement in his family when his father brought home a mango. Luckily, they knew to wait until it was ripe! It just goes to show: memories of growing up can be very similar, whether they were made in Tokyo or Edinburgh! Takahata is masterful in selecting recollections that resonate with viewers of many ages and backgrounds. We are inevitably drawn into Taeko’s story by its parallels with our own – her nostalgia fuels ours.

As I approach the age of 27 myself, I find that this film draws ever closer to my heart. If a trip down memory lane is what you desire, Only Yesterday may prove the perfect starting-off point.

the

/ page 7

FILM dIspatch

REVIEW

“Takahata is masterful in selecting recollections that resonate with viewers of many ages and backgrounds.”

enys Men (2022): a sLIce oF Land FILM

By Rhys Monaghan

How does one discuss, and remember, a film that resists both discussion and memory? Rhys Monaghan unfolds the layers and lands of time that confound in Mark Jenkin’s latest feature, Enys Men.

Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men (2022) does not lend itself easily to interpretation in an 800-word article, largely because it does not lend itself easily to interpretation at all. This film’s elusive multiplicity is best captured by the difference between Peter Bradshaw and Mark Kermode’s Guardian reviews. Both commentators have high praise for Jenkin’s island-based Cornish ‘horror’, yet these praises fall on completely different aspects of the

film. Bradshaw celebrates the film for the tale it tells around the lone woman (Mary Woodvine) who populates most of its scenes; a volunteer performing a daily inspection of an island whilst, ostensibly, being haunted by events that are occurring and have occurred on and around it. Bradshaw takes a view of everything else as essentially just pretty, eerie colours on a pretty, eerie island, that help to tell this story. For Kermode, however, that tale is set alongside a backdrop which utilises its prettiness and eeriness to communicate an equally central complex and a “richly authentic” Cornishness. In a film so resistant to cohesive interpretation that the word ‘frustrating’

memory page 8 /

features in almost all of its reviews, these opposing perspectives are not surprising. But their distinctions hit upon the source of Enys Men’s mystery: the question of its protagonist. This is a film which misdirects as to who or what is at its centre in order to immerse the audience in the accrued, and accruing, multidimensionality of localised land. Through this immersion, the film demonstrates how any relation to that land embodies the land’s past, its present, and its future. When watching a film in which almost all of the scenes show just one woman wandering around an island performing variations on the same routine, the assumption is that we

have, to at least some extent, been shown our protagonist. Yet Woodvine’s character exists in this film

exclusively as a symbol of how the individual relates to the film’s true protagonist: the island. Throughout this film the volunteer is bombarded with a set of visions which conflict and recur: she returns to her house each day and eats and sleeps there, yet also regularly sees it dilapidated; she sees a young woman ambiguously either her daughter or herself at a younger age; she sees miners dead underground, and local women from a previous century on the hills; and she regularly encounters the boatman, who delivers her fuel, both as a sexual partner and a drowned corpse. On the surface, these conflicts – which remain unresolved – produce a narrative which refuses to prioritise one singular chronology or plot, instead presenting pieces of differing chronologies and differing plots which interrupt and merge with each other, and, consequently, all come to be presented as equally true. In this jarring and sustained interspersion, each moment is an isolated feature within the chronology of the narrative, and yet also a foundational, deliberately employed aspect of it. This dichotomy, combined with the way in which the visions also blend past and future, renders the film atemporal – or, rather, gives it a kind of

the FILM dIspatch / page 9

“This is not a film which aims at any kind of linear narrative in the first place.”

meta-temporality, encompassing all time simultaneously.

With the events depicted in all of these visions being rooted in the inhabitants of the island, as well as the aging of aspects of the island and the threats posed by the island’s nature, our true protagonist emerges: the island itself. This is only emphasised by

the closest thing to a definitive present-day narrative offered by the film being the volunteer’s daily routine – a monitoring of the island which merges science and superstitious ritual.. Unnamed, her existence consists exclusively of living on, and interacting with, the island: her essence is local. With the land and its local centred, it

becomes clear that this is not a film which aims at any kind of linear narrative in the first place. Enys Men’s objective is instead to immerse the viewer in a symbolic experience of the relationship between the two: the way in which belonging to a piece of land constitutes an embodiment of its past, its present, and its future simultaneously; the way in which the local’s present belonging is bookended by their absence; and the way in which the land’s traditions and natural phenomena possess an immortal, foundational role in the formation of localised identity to the point of being deific. Crucially, this is a relationship which both bonds (as demonstrated by the symbiosis of the island’s lichen growth being mirrored on the body of the volunteer) and haunts (captured by the incongruity and unpredictability of the visions, as well as the gorgeously unsettling sound imagery). It is the sublime uncovered in the roots of the quotidian, and is best captured in voices through the radio interchangeably begging for a connection,

memory page 10 /

“Enys Men’s objective is to immerse the viewer in how belonging to a piece of land constitutes an embodiment of that land’s past, present, and future”

(‘are you there?’), and suggesting an inevitable destruction (‘Mayday! Mayday!’).

In a film whose director is emphatically Cornish and whose title is Cornish for ‘Stone Island’, the centring of the relationship between a local and a Cornish island is likely intended as a centring of Cornish-ness. Yet, in exploring that relationship, Jenkins has created a film which transcends any specific local or locale, instead articulating the broader dichotomous human relation to place, in which belonging to the transhistorical memory of a location simultaneously welcomes and terrifies.

the FILM dIspatch / page 11

REVIEW

turnIng red (2022): a revIew

By Michaela Flaherty

Michaela Flaherty is catapulted back into her teenage years as she reviews Disney Pixar’s fantastical take on the coming-ofage narrative, Turning Red.

I think it’s telling that my dad, whose taste in film I generally trust, thought Turning Red was “worse than The Good Dinosaur” (a low, low blow), while I was truly moved.

Thirteen-year-olds are cringeworthy, which is maybe off-putting for

some viewers (like my dad), but that’s where the film’s character really kicks in. Turning Red embraces awkward teenagerdom: swooning over celebrities and fictional characters, grappling with crushes, and gasp navigating puberty. “Why do they need to make a movie about periods?” says my dad and plenty of disgruntled viewers. To which I reply, “Because this would’ve helped me ten years ago.”

Watching Mei interact with her fellow “Townies” was like reliving my

memory page 12 /

dorky middle school years spent with my equally dorky friends, poring over SuperWhoLock Tumblr, practicing how to ask our moms for permission to hang out, and reenacting our favorite musicals. There’s such beauty in films that draw from real-life experiences, and I’m glad I watched Embrace the Panda: Making Turning Red beforehand; it made me truly appreciate the honesty of Turning Red, which primarily owes itself to the film’s all-female leadership. (How very #girlboss of Pixar.)

From “And Aaron T. and Aaron Z. are, like, really talented, too!” (apologies, Louis and Liam of One Direction), to Jesse’s degree in ceramics and two kids at home, everything about 4*TOWN made me giggle. The Turning Red team completely nailed 2000s and 2010s boyband culture— especially how comforting it can be for young girls to seek solace in music and fandom that is typically dismissed as “silly” or “shallow” (because God forbid, they enjoy anything remotely popular).

Though Turning Red focuses on mother-daughter relationships, Mei’s relationship with her father made me tear up. The scene where they watch her goofy videotapes nails the affirmation most girls want to hear from their fathers (or male role models) during their turbulent teenage years. In my experience, information about

periods and other aspects of female puberty are often passed down from mothers (or female role models) to young women as “secrets” they must quietly handle and guard. This only perpetuates shame about something natural. Though my dad hated Turning Red, he’s ironically the person who bought me my first pads. So shoutout to my dad, Mei’s dad, and every other guy who isn’t afraid to overcome masculine stereotypes and openly uplift the women in their lives. I’m not intending to portray men as heroes to girls going through puberty; girls are plenty capable of being their own heroes, and addressing internalized misogyny is an entirely separate (but important) issue. Nonetheless, Turning Red sparks an important dialogue about the impact of patriarchy on young girls at a critical developmental stage of their lives, and of the importance of subverting the gendered status quo.

Turning Red is ultimately a sweet movie cleverly infused with subtle social commentary. Don’t mind me while I sing along to 4*TOWN on the walk to school tomorrow. (The transition from the Cantonese chanting into Jordan Fisher’s crooning in “Pandas Unite / Nobody Like U [Reprise]” has got to be laced with some sort of music theory crack). Shoutout to Pixar for somehow making me nostalgic for reading Harry Potter fanfiction at theater-kid sleepovers and crying over stained jeans in a middle school bathroom.

the FILM dIspatch / page 13

REVIEW

“Turning Red is ultimately a sweet movie cleverly infused with subtle social commentary”

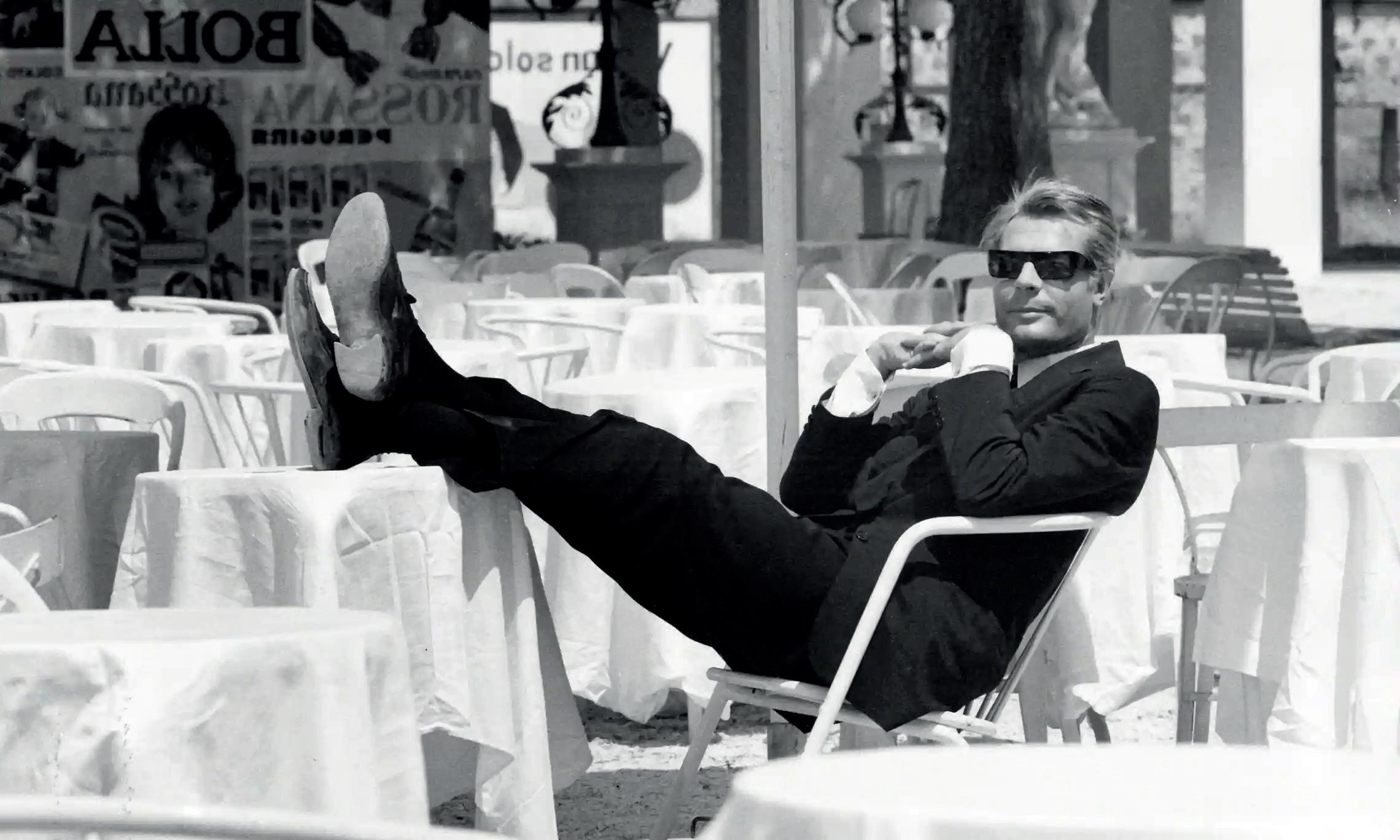

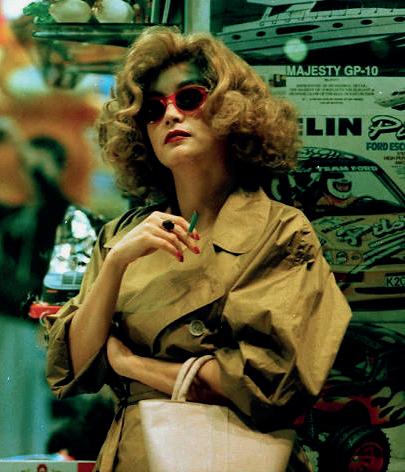

chungkIng express: a revIew

by Wifak Gueddana

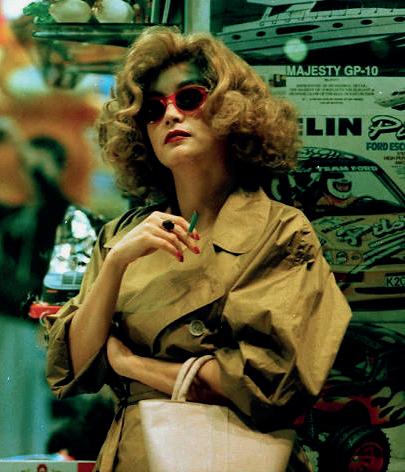

Wifak Gueddana looks at Wong

Kar Wai’s classic Chungking Express and how it explores the fractured memories of the heartbroken by narratively and technically playing with time, space, and narration.

In Chungking Express (1994), Wong

Kar Wai devises two mise-en-scenes, two stories, with the same building blocks. In the first story, a young man is suffering from heartbreak and the pain of his unfulfilled desires, reminiscing about the heydays of his past relationship. His life is now akin to a bittersweet memory, like the taste of expired tinned pineapples. Wong Kar Wai’s boyish, glamorous and playful personality transpires. He likes to let visuals and cinematography take charge of the viewer’s emotions, deconstructing the narrative, jolting frames into a frenzy (distorting time, breaking the unity of the storyline and mixing genres). This is not a film, but morsels of romance, gangster-thriller, documentary and a mood piece. The viewer, rather than the filmmaker, sticks everything together, a scatterplot of images: a blur of fast-paced

action; a dodgy bar; crowds of people in cramped, dark alleyways; as well as a fabulous Bridget Lin, hiding behind a dishevelled blonde wig, black sunglasses, and a beige coat with high heels (all fusing in my mind the vague memory of Who

Framed Roger Rabbit’s luscious starlet cartoon – also a twilight-good-&-bad character in his film). The images pump up the suspense, but everything and everyone is under Wong Kar Wai’s tight leash. The protagonists operate within two discrete realities, and the viewer cannot anticipate their reunion. She is a drug trafficker and a killer chasing after illegal Hong-Kong immigrants; he is a cop living in a delusion of his own making. There is one encounter, but it is doomed: their story ends before it has even started. The pace of the visual sequences quietens in the second story. The viewer gets a breather, and Wong Kar Wai reshuffles the blocks: the film turns into a straightforward romcom. This is best demonstrated by the body movements and facial expressions of his cast. They are the core of the second half of this film, and loved by the camera; their performances give frames a still-like quality and a sort of slowness, producing the opposite effect to that of the first half. Tony Leung plays a sweet young policeman yearning for his former lover. She is a sexy stewardess who is too busy switching planes in-flight to acknowledge his affections. Following her departure, random objects in his house seem to

memory page 14 /

cry out from having been left behind – tender gimmicks which reminded me of a Disney childhood favourite, The Beauty and the Beast. Within this element of the film manifests Wong Kar Wai’s childish, provocative sensibilities. The heartbreak is not long lasting, of course. The ‘cute-dreamer’ sandwich-bar waitress, Faye Wong, tiptoes her way into the policeman’s den. Messing with his house, she starts to literally leave traces of her presence, becoming a part of his domestic life, while he remains ignorant (or at least pretends to be). Again, the lead couple can only engage in brief encounters while they lead their separate lives. As before, they oper-

ate in parallel rather than together, but this time, they also share a connection – in the form of the physical space of his home, which suggests the possibility of a happy ending. Wong Kar Wai’s mastery is in boxing things up, fitting characters into arch roles, whilst changing their faces and personal stories, and dissociating genres, in order to cleverly reshuffle and integrate them, producing a more impactful narrative. His films are visual reconstructions that are akin to playing Lego blocks, and yet his films are also personal, oozing his own sense of nostalgia and irreversible sadness –which we retrieve in full power in In the Mood for Love (2000).

For Wong Kar Wai, there is no such a thing as realism: only liminal twilight spaces, and fragments of characters’ memories. The first part of this film contains a visual montage that is utterly non-linear, sometimes

the FILM dIspatch / page 15

“

[Kar Wai’s] films are visual reconstructions that are akin to playing Lego blocks”

with the male lead as a narrator, and sometimes centring around the female lead. Yet in both sequences, time is distorted like in a dream; visuals are sped up, to accelerate chronological sequencing, or they are slowed down. These temporal shifts relate to the perspectives of different characters, i.e. what he/she remembers and feels. In the second part, time becomes immaterial. How could it be otherwise, when a tattered kitchen towel, bathroom soap and a uniform shirt in the cupboard are all crying after the lost lover? Their yearning nostalgia (despite their being inanimate objects) indicates to us the way in which time has become irregular and bent out of its typical shape. Time is boundless

too: it has no grasp on this storyline. The tale starts well before the events on screen, and continues long after them, a sort of epilogue offering the viewer the closest thing to a conclusion to the story. The film’s visuals are fragments of the characters’ memories. They are individualized and dissociated when characters become antagonistically related, resulting in a film with two orders and two modes of existence that run in parallel (1st part). When characters are meant to converge (2nd part), their memories are brought together, fusing into unity, and forming a timeless space of connection.

To conclude, one could argue that Wong Kar Wai’s cinematography (in this film and in all of his works) is not limited by narrative scope or form. It is composed of visuals that create time, capture characters’ memories and turn them into the most appealing stories.

memory page 16 /

“

For Wong Kar Wai, there is no such a thing as realism: only liminal twilight spaces, and fragments of characters’ memories”

the FILM dIspatch / page 17 REVIEW

aFter LIFe: the sIgnIFIcance oF

MeMorIes to soMeone experIencIng grIeF

by Aisling McDonagh

memory page 18 /

In this welcomed analysis of a TV series, Aisling McDonagh explores the relationship between mourning and memory in After Life (20192022), a show that delights in the occasional proximity of laughter and pain.

After Life (2020-2022), a limited series written and created by Ricky Gervais, follows a man called Tony whose grief-induced depression becomes overwhelmingly dominant throughout his everyday life. Viewers watch as Tony pushes away those around him, whilst trying to cope with the unfair realities he faces as a widower, after the loss of his soulmate, Lisa. Although the show is ultimately grounded in the story of a suicidal man forcing himself through life, the series is not nearly as dark as it sounds. It actually tackles grief quite beautifully, which is something I never expected from a comedy series on Netflix.

Each episode is an amalgamation of vulnerability, intense grief, and sadness, but these moments are quickly and harshly contrasted by the outrageous humour, which is somewhat reminiscent of Ricky Gervais’ Golden Globes speech in 2020. “Shockingly outrageous”, in all honesty, that’s the first phrase which comes to mind when referencing the humour in this

show. From hearing Ricky Gervais’ character call a primary school child a “tubby little ginger cunt”, to watching him argue with a waitress about whether adults can order kids meals, it really is hilarious. Ricky Gervais often utilises shock factor to his advantage with his humour in this show, so I think at first it is easy to ignore other dimensions of his characterisation, and it is hard to see past his blunt, humorous nature. However, as the show progresses, we understand Tony to be much more complex, both when he is alone, and through the progression of his friendship with Anne (played by Penelope Wilton).

The relationship shared between Tony and Anne follows the more positive side of coping with grief. Anne, also a widow, becomes a maternal figure to Tony, guiding him in his daily life. She tries to help him understand life the way she has learned to, the way Lisa would want him to. Memory becomes a crucial part of their friendship, as they regularly reminisce together about their relationships with their deceased partners. Penelope Wilton’s character has a comforting presence to Tony and, to some extent, the viewer too. As an older, wiser character, she becomes very likeable to both the audience and Tony as the show goes

the FILM dIspatch / page 19

“

Each episode is an amalgamation of vulnerability, intense grief, and sadness, [...] quickly and harshly contrasted by the outrageous humour”

on. Anne is complimented by other warm characters such as Tony’s love interest, Emma, and his colleague, Sandy, who all play vital roles in ‘persuading’ Tony to find peace in the life he has been given. However, these people are contrasted by the ludicrous presence of the characters played by the comedian’s Joe Wilkinson and Roisin Conaty. This creates an interesting dynamic throughout the show, where there is quite a divide between these characters and their ‘tropes’. And when characters like Anne step out of the expected boundaries of their characters every now and then and make an outrageous joke, they become even more of interest to the viewer.

Each season we learn more about Tony’s late wife Lisa, through old videos depicting memories of them together. The series cleverly juxtaposes videos of Lisa, healthy and happy, with those of her in hospital giving Tony advice on how to survive life without her. I think it’s here that we understand how important that little black laptop really is to Tony, like a memory box. He grasps onto it, so tightly, almost as if it were Lisa herself, a way he can keep a hold of her and keep her close. It’s scenes like

this, where you realise how important a video, a picture, and thus a memory is to someone grieving. It’s scenes like this, where you forget about the

outrageous comedy prior, and start to feel empathy for Tony as a character. I think the beauty of these scenes is that they provide a break from the comedic chaos the rest of the series fulfils. The memories in these scenes are not always ‘big’ or ‘beautiful’, sometimes they are the simplest videos of Lisa lying on the sofa laughing. As you watch Tony laugh or cry, you too become emotional because it seems so real.

However, despite such heart-warming flashbacks of Tony with his wife and the help characters like Anne attempt to offer him, Tony’s relentless negative attitude towards life can become frustrating at

memory

page 20 /

“Tony’s relentless negative attitude towards life can become frustrating at times. And I think that is the point”

times. And I think that is the point: this show beautifully and realistically captures the pain of grief. The people around Tony push a narrative of “we understand, but you need to move on”. But grief just isn’t that easy. This show really encompasses that, and it is a comfort to have such experience captured in media. This is what made the show an enjoyable watch for me, because, though at times I found his character quite frustrating, I continued in the hope that we would see him progress to peace, as Lisa wanted.

The ending of the show was something special. As expected, Tony reaches a better place but continues to fight his battles. We see this in even the smaller, or somewhat insignificant parts of the season, such as when teases Lisa about there not being an “afterlife”. Scenes like this show that memories can be both healing and comforting to someone grieving, but also wildly disconcerting. The last season, especially, encapsulates the sense that even when you get to a better place, a better place isn’t perfect, because life itself isn’t.

If you want to laugh and cry, this is a series to watch. Though I would describe it as lighthearted, (which is ironic considering it follows a suicidal man whose wife has died of cancer), the witty narrative, the heartfelt conversations, and the memories throughout make it seem realistic and enjoyable. And though some may see it as a comedic facade to what is, ultimately, just a sad story, I think it was more than that. I think it was a different piece of comedy to the media that is often seen on Netflix today, be-

the FILM dIspatch / page 21

REVIEW

cause I certainly didn’t start watching the series thinking I would be so fond of a story about a widowed man, but to my surprise, I was.

BaFtas gave Me a reason to actuaLLy watch the oscars thIs year

By Yasmeena Sulaiman

By Yasmeena Sulaiman

memory page 22 /

how the 2023

In the midst of the film awards season, Yasmeena Sulaiman looks to the BAFTAs with surprise and anticipation, and wonders whether this year they might be a sign of Oscars surprises to come.

The cinematic awards season is a time to reflect on the films that have truly stood out amongst others debuting in the same year. With release after release across both theatres and streaming sites, which movies can we remember, and why? The awards season aims to spotlight films that have left visceral impressions on audiences and critics alike, as well as conveniently leaving behind a watchlist for anyone interested in cinema to look back on and reference continuously.

Dominating with seven wins and 14 nominations, All Quiet on the Western Front (dir. Edward Berger, 2022) was adored by voters of the BAFTAs (British Academy of Film and Television Arts). Picking up wins in categories such as Best Sound, Cinematography, Original Score, Adapted Screenplay, Director, and Film Not in the English Language, it was unsurprisingly crowned Best Picture. But with a poignant film like The Banshees of Inisherin (dir. Martin McDonagh, 2022) being in the race, I was shocked to see it given the award for Outstanding British Film but not Best Picture. This award show genuinely astonished me with its adoration of the German film, especially over the culturally and critically popular Everything Everywhere All

at Once (dir. Daniel Kwan, Daniel Scheinert, 2022). Everything only received the Editing award at the BAFTAs, yet obtained above-the-line accolades at multiple other film awards such as the SAG (Screen Actors Guild

“Sitting in the IMAX theatre eating my butter-drenched tub of popcorn while going along with Tom Cruise [...] is an underrated and electrifying experience”

Awards) and Critics Choice Awards. Despite this success, the BAFTAs preferred the aptly titled and pensive All Quiet on the Western Front. It is a solid, devastating film, but I have some contentions with a couple of its wins and other choices the BAFTA voters made.

All Quiet on the Western Front won Sound but, as an American, I can proudly state that it should have gone to Top Gun: Maverick (dir. Joseph Kosinski, 2022). Sitting in the IMAX theatre eating my butter-drenched tub of popcorn while going along with Tom Cruise in whatever state-of-theart fighter jet he pilots is an underrated and electrifying experience, that is amplified by its sound design.

Original Score is the second win

All Quiet earned that should have gone to another film. Again, the film has a score that deserves credit, but the clear winner was Babylon (dir. Damien Chazelle, 2023). The score by

the FILM dIspatch / page 23

Justin Hurwitz is epic, lively, and explosive — a wondrous facet of storytelling in the 3-hour historical Hollywood drama.

In addition, I have to mention the confused awarding of the Casting category to Elvis (dir. Baz Luhrmann, 2022). I concede that the casting of Austin Butler was paramount to the integrity of the entire film; however, the casting of Tom Hanks led to a mediocre performance. Comparatively, Everything Everywhere All at Once knocked it out of the park with its core four actors: Michelle Yeoh, Ke Huy Quan, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Stephanie Hsu. This awarding to Elvis

is even more incoherent since Austin Butler won Leading Actor. Initially, I did not see All Quiet on the Western Front performing outstandingly at the Oscars. With the deep appreciation it garnered at the BAFTAs, I wonder if this is a sign that Everything might not sweep the Oscars as predicted, especially with Elvis getting a lot of attention and even The Banshees of Inisherin snagging the Supporting Actor and Support-ing Actress wins over Ke Huy Quan and Jamie Lee Curtis in Everything. These losses on Everything’s part, and the massive wins afforded to All Quiet, lead me to believe that it might be a threatening contender in this year’s Oscars, and I will gladly watch the ceremony to see if Hollywood surprises (or enrages) me.

memory page 24 /

“

All Quiet [...] might be a threatening contender in this year’s Oscars”

the FILM dIspatch / page 25 SHORT PIECE

a MeMory oF dIaLogue

By Weiyi Wang

Looking back to a conversation between two characters in Jean Luc Godard’s Vivre sa Vie (1962), Weiyi Wang interrogates the camera’s relationship to the emotionality within the sequence.

Regarding dialogue, rather than discussing the contents of the characters’ conversations in Vivre Sa Vie (JeanLuc Godard, 1962), I will instead discuss one of the episodes that features two characters having a conversation. Different from Hollywood’s presentation of the passing of time (labelled the movement-image by Deleuze), Godard focuses on the experience of

life. In Godard’s films, viewers can feel the moment of time and emotion change through the cinematic devices he uses to portray the passing of time. In this episode (Fig. A), Nana (Anna Karina) and Raoul (Sady Rebbot) express their opinions of one another to each other. Raoul’s back is turned away from the camera, and we can only follow Nana’s dialogue and facial expressions to see the changes in the plot. As they talk, the camera switches from the left side to the right and back again, a very distinctive and elegant movement, as if Godard’s camera language is closely linked to the slightest change in the protagonist’s inner emotions. Each camera movement is linked to Nana’s psychological expectation that Raoul may express his opinion of her. We feel that she expects what Raoul is saying, what Raoul is feeling about her. In the second episode (Fig. B), the camera shifts to the side so that we can make out the faces of both of the characters. This is the first time that

memory page 26 /

Figure A

we are able to see Raoul’s face and this gives the later episode a connotation of more depth. The camera moves to their separate sides as they talk, revealing only one person’s face rather than encompassing two people and an entire scene. The episode is more like a test straight into Nana’s inner heart, a test of Raoul’s emotions for Nana, of whether he loves her. After a period of conversation, Nana’s emotions and the expectations she had of her conversation with Raoul are left unsatisfied. Raoul wants Nana to smile, and Nana expresses that she does not want to do.

on Nana’s face. However, as a generic male figure Raoul does not come across as sentimental; he is confident and he is the one who wants to take advantage of Nana. This is conveyed to the viewer by the glimpse of a smile in his expression.

These episodes display the emotional experience of the protagonists during the passing of time. I cannot help but wonder if Kar-wai Wong’s In the Mood for Love (2000) has taken a page from Godard’s techniques in Vivre Sa Vie.

For the first time, their faces appear together in one frame (Fig. B). They stare at each other, and gaze into one another’s eyes, which are full of emotion. Within this scene, Godard proves to the viewer, and to the film, itself that no dialogue is needed. The shot is static – everything is static in this moment. We just need to enjoy this moment and observe the slightly depressed feelings that are expressed

the FILM dIspatch / page 27

“Godard proves to the viewer, and to the film, itself that no dialogue is needed”

SHORT PIECE

Figure B

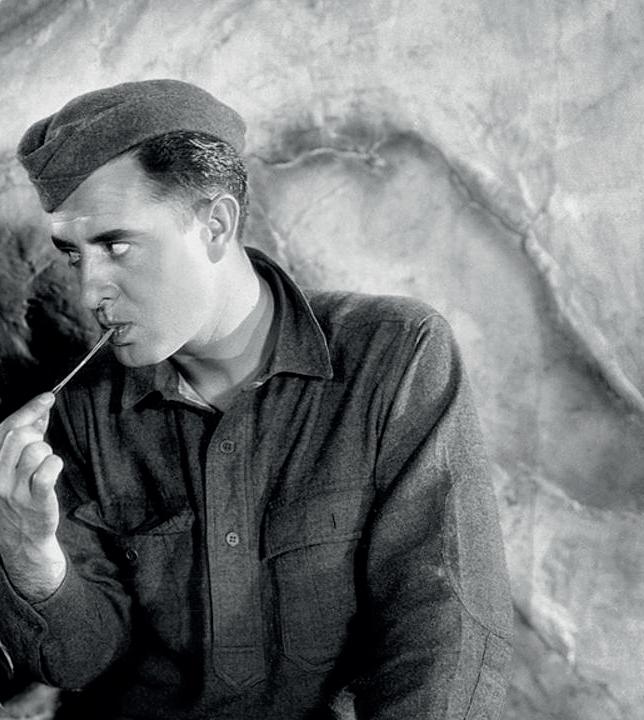

IMagInIng nothIng: MeMory In oLdBoy (2003 )

by Ethan Radus

by Ethan Radus

memory page 28 /

In Park Chan Wook’s Oldboy, memory seems to be a way of navigating a mystifying present. Ethan Radus argues that in remembering something we do not transport ourselves into a fixed history so much as we begin to reckon with our present day lives.

Often, we subjugate the present to the past, and memory assists us in this operation. The present is pre-determined, lacks affective complexity, and can be rationally explained. The past is oneiric, transcendent, and feels visceral to us. It is emotion heightened beyond the bounds of what we could possibly feel now, always far better or worse than what we experience in the moment. Memory thus taunts the cold, banal present with sepia-toned warmth, with sights and sounds that seem lost or archaic, stuck in the context of their origin, never again to be felt or experienced. The past is poetic and beautiful, while the present is prosaic and boring. But why is memory an abstracted version of reality and not reality itself? Perhaps it isn’t an agent of the past either, quietly

acting on us as we stare blankly at our unfolding lives. Instead, maybe it is simply the word we use for our inability to understand our confusing lived experience: memories helping us to reckon with (and decipher) our present, not retreat from it.

Oldboy is a film about a man who does not remember something he has done that is insignificant to him, but extremely important to somebody else. For this, he is sentenced to 15 years abduction and imprisonment, wherein he is incarcerated in a hotel room with only a television for company. Upon release, he is an entirely different man. Woozy drunkenness has metamorphosed into wizened insanity, pathetic grumbling into a silent, animalistic violence. His initially diminutive physicality has been shed, leaving an arched, hulking strength. We do not know why Oh Dae-su was imprisoned and, like him, we are trying to figure this out. As our protagonist sifts through his memory for clues, we intuitively hunt and collate them too, exercising our own faculties of memory over the course of the film.

the FILM dIspatch / page 29

Memory is therefore the fundamental engine of narrative. Once released, Dae-su is given 5 days to work out his wrongdoing, lest he be punished once again. The story recalls Kafka’s The Trial, in which an innocuous clerk is approached unexpectedly by government officials who tell him he is under arrest and sentenced to death. The ensuing nightmare is less a fear of the present than a frantic clawing toward some obscure answer lurking in the past. Why me? What have I done? Memory, which often offers explanatory feedback to real-time experience, sits back out of view, silently watching, perhaps not even there at all. Dae-su’s captor, Lee Woo-jin, embodies this temporal voyeurism as he silently surveils, dropping breadcrumbs whilst disappearing from view. Dae-su becomes Woo-jin’s plaything, as the latter coaxes half-formed memories from our protagonist. Maybe, then, memory does not draw us away from our present. Instead, maybe it is urgent, contemporary, and current. Park Chan-wook’s stylistic direction emphasises this, as images from the present bleed into the past, and seemingly linear subplots suddenly veer backwards, forming self-contained episodes. Visual motifs recur like poetic refrains, constantly threading the past back into frame, as though only one temporal frame exists: the now. Watching as the film develops its own memories,

we become accustomed to thinking of them as native to the present, rather than as a long-lost past. Chan-wook trains us into thinking in, and through, memories. Desperately looking back, then, is not the answer for Dae-su; his memory is a thought process native to the present, both shaping it and being shaped by it.

Like Proust and his madeleine, much of Dae-su’s past is condensed into sensory phenomenology. This is most evident when he seeks out the dumpling restaurant that fed him during his imprisonment. Unlike Proust’s involuntary experience of sudden recollection, Dae-su devours dumpling after dumpling, eating his way into his past. Dae-su’s first meal after his release is a live squid – “I want something alive” he demands of the sushi chef, an order that recalls his persistent threat to devour the flesh of his

memory page 30 /

“Chan-wook trains us into thinking in, and through, memories”

captor. As Roger Ebert pointed out, Dae-su wants the squid’s life, not its meat, and this enunciates his critical mistake. Voraciously looking into his past and seeking to restore the life he has lost, Dae-su neglects what is right before his eyes. The sushi chef, Mi-do, whom he will soon fall in love with, is his daughter.

The Ancient Greeks believed that one stands with one’s back turned to the future, facing the past. We do not look towards the future, because how can we? It is oblique and unknowable. Dae-su stands thus, and unwittingly falls in love with his own daughter. Chan-wook twists the past and present into a knot, tying Dae-su into a contorted, tortured position. Daesu’s sexual mesalliance is ultimately explained to him, and he becomes a wretched creature, cutting his own tongue from his mouth. Better not to

talk at all than to talk with the loose tongue that incited this chaos, in the mouth that kissed his own daughter’s. The strength and hardness he achieved through his imprisonment is gone. He is now a blood-soaked, incestuous dog, crawling on all fours. The pull of the past and present has rent and ravaged him. Dae-su’s tragedy is his inability to see memory as indistinguishable from his present. His life is partitioned by his imprisonment, constituted by a “before”, (which he can no longer relate to), and an “after” (which is consumed by his vengeful anger). This temporal partition blindsides him. Even though Woo-jin sneeringly reminds Dae-su to ask not why he was imprisoned, but why he was released, implying that his past infractions somehow exist before his eyes in the present, Dae-su cannot oblige: his back his

the FILM dIspatch / page 31

turned. Woo-jin’s plan mobilises this; he anticipates Dae-su’s blind rage, because he shares it. “How’s life in a bigger prison?” he asks Dae-su over the phone, soon after his release. The question seems directly mocking, but bears a hidden irony: Woo-jin is similarly incarcerated in that bigger prison, living in a temporal deadlock with his past. By engineering Dae-su’s incest he reveals his own sexual liaison many years earlier with his sister Lee Soo-ah, destroying himself too, as the two men revisit this sin.

Memory is gestation. It develops and changes. Sad memories can become happy. Happy memories can become sad. For Soo-ah, this is literalised by her phantom pregnancy. Filled with retrospective guilt at the consensual affair she had with her brother, her belly grows and brings forth evidence of their illicit relationship. Evidently, memory is not a place we retreat to by choice, or a static mu-

seum of experience: it is an active, flexing, organic presence that imposes itself on us constantly. Soo-ah’s guilty memory brings about her death, and Woo-jin’s obsession with punishing Dae-su for spreading rumours of the incestuous affair dictates his cruel life henceforth. Woo-jin does not move on or eradicate his memory, nor does he purge Dae-su of the memory of witnessing the sibling’s sexual affair; all he does is transfer these intense feelings into the next chapter of his life, where they equally dominate and destroy. That’s life in a bigger prison.

We are left feeling sorry for Mido, Dae-su’s poor daughter. She does nothing wrong but suffers immensely. Perhaps she is the emblem of memory’s illusory distance: an idealised past that doesn’t exist anymore, that is in fact rooted in the disappointing terrain of present reality. This is how memory works. It lies to us that our lives are split between the now and the then. But it is all now. When we think we are escaping the present, we are just extending it in a different direction. Oldboy takes a page out of Samuel Beckett’s book in that way, constructing life around a temporality outside of the one you inhabit, which only seems to fracture and pollute the present, turning it into an absurd, purgatorial nightmare. Beckett’s pur-

memory page 32 /

“It is all present. That is the journey, and the meaning of it all, and, perhaps, the meaninglessness of it all.”

gatory is linguistic, Chan-wook’s is physical. The former thickens language into a senseless mass where characters aimlessly wait for things to happen, whilst the latter does so anatomically, as bodies violently collide, atomise, and breach sexual taboos. Escaping the present through memory enables this destruction of its order and stability.

It is all present. That is the journey, and the meaning of it all, and, perhaps, the meaninglessness of it all. As Dae-su says himself, in true Beckettian fashion: “You need not worry about the future. Imagine nothing”. The same can be said of the past in Oldboy. Facing the past for too long means submitting to this nothing-ness; Dae-su does so, and we find him vacantly staring into a snowy wilderness, unable to speak at the end of the film. The emptiness of his past has dictated the emptiness of his present. He no longer imagines nothing, he lives it.

the FILM dIspatch / page 33

FEATURE

reMeMBerIng avatar’s IMpact In LIght oF avatar: the way oF water (2022)

by Flora Stokes

James Cameron’s overwhelmingly blue sequel recently burst onto the big screen, but can it measure up to its predecessor, which continues to hold the record for the highest grossing film of all time? Flora Stokes isn’t so sure…

Being a student, it is a very rare thing for me to be awake before 9am. To ask you to imagine me sat in the squishy leather seats of the Edinburgh Cineworld IMAX cinema at 7am sharp is to ask you to imagine something just short of a miracle. As it happens, there I was bright and early, awaiting the cinema’s first screening of James

memory page 34 /

Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water. The original Avatar film has (I’m not ashamed to say) remained one of my favourite films of all time, despite having a general lack of appetite for anything that situates itself within the action genre.

To avoid embarrassing myself by revealing the extent to which my emo-

tions were riding on this sequel, I will simply say that I was deeply disappointed. Note to self – if you have 250 million dollars and over 180 minutes of screentime at your disposal, don’t spend less than ten minutes establishing your plot via hasty voiceover. Perhaps, after thirteen years of waiting and over twenty rewatches of the

the FILM dIspatch / page 35

original film, my disappointment was inevitable. 21st century Hollywood’s unhealthy addiction to sequels and spin-offs frequently leaves fans of various franchises disappointed – why should this attempt be any different?

The sequel has provoked deeply divided critical opinions. Empire’s Nick De Semlyen describes it as a ‘phantasmagorical, fully immersive waking dream of a movie’, whilst the somewhat less-taken Telegraph critic Robbie Collins felt he was being ‘waterboarded with turquoise cement’. My own response leaning strongly towards the latter, I want to interrogate what it is about the original Avatar that has had me fiercely defending it for over a decade, despite the risk such defence conjures towards any reputation I may hold as a film student. In remembering the film of my youth, I hope also to prove why the sequel is not merely a sub-average action film but a missed opportunity to continue to impart a meaningful and relevant message regarding the state of our planet.

Here’s the thing. As we know, Hollywood has, arguably, been seeking a golden formula for the “perfect” (i.e. highest grossing) film for some time now. Recall their commercialisation of the star system during the 1920s with the intention of drawing in female audiences, or the patriotic

musicals that were prolific throughout the Second World War. Or, a favourite of mine, American International Pictures’ decision to target young male viewers in the 60s, on the peculiar assumption that girls will want to watch what boys watch, and younger boys will want to watch what older boys watch. Regardless of the method, Hollywood is, and always has been, out to make the big bucks. In many ways (and as evidenced by it being the highest grossing film of all time) Avatar is an example of Hollywood coming pretty darn close to cracking that golden formula.

Putting aside the film’s oft-discussed visuals, what impressed upon me most as a pre-teen, and what has stayed with me since, are the film’s complex characters. Opening with a monologue from protagonist Corporal Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), the film lulls the viewer into what appears to be a typically phallogocentric Hollywood narrative. It is a pleasant surprise, therefore, when the likes of Zoe Saldana, Michelle Rodriguez and Sigourney Weaver proceed to command much of the screen time. Their characterisations vary greatly, but none can be read as passive. Sully’s survival and success is dependent on the actions of each of these women. It is a disappointment, therefore, to see the depressingly essentialist gender roles that Cameron chooses to present in his sequel. Saldana’s character Neytiri, once a fearsome and prickly hunter, is reduced to a passive, fearful mother alongside Kate Winslet’s equally passive and fearful motherto-be. Neytiri’s inner turmoil towards

memory page 36 /

“Regardless of the method, Hollywood is, and always has been, out to make the big bucks. ”

the beginning of the film as she is faced with fleeing her people in order to protect her children, is quickly and decisively quashed by her husband, never to be mentioned again.

Sully and Neytiri’s daughters spend the majority of their time watching their brothers engage in painfully hypermasculine brawls (which would not feel out of place on the basketball courts of High School Musical), or being kidnapped and rescued, repeatedly. Cameron appears to have forgotten that the power of representation lies not merely in visibility but in conveying varied understandings of different groups. Put simply, in the former film, women are to be feared and admired; in the latter they are to be protected.

A further strength of the original film is its critique of American exceptionalism, a process by which, according to theorist Donald E. Pease, America comes to be seen ‘as the fulfilment of the national ideal to which other nations aspire’. Clear allusions to Earthly acts of colonisation, such as the violent attempts by American settlers to assimilate the Native American peoples, can be found in the brutality of the invasion of Pandora. The film’s invasion is led by the fearsome Colonel Quaritch (Stephen Lang), who acts as the epitome of militaristic aggression. This dichotomy between Evil Humans and Good Indigenous People is ham-fisted in a way that Hollywood action films often are, yet still evokes important questions regarding community and the relationship we have with our planet. Cameron attempts a similar evocation in the sequel, but such messages

are muddied by an Americanisation of the Na’vi – the dialogue is littered with phrases like “dude” and “bro” –and weak rehashings of the first film’s plot points (spoiler alert – the baddie is the same guy, just without the ideological force of the human race’s greed behind him!)

The sequel’s assimilation of the Na’vi into American culture, as well as its dependency on normative ideals and archetypes of familial structures, is what results in the film’s inability to convey any real urgency in its message regarding climate change. The film’s exhausting “think of the children!” plea reminded me of queer theorist Lee Edelman’s condemnation of the use of the mythical and innocent “Child” in political agendas. Aligning itself with Edelman’s notion of “reproductive futurity”, The Way of Water dislocates the ever-pressing issue of climate change onto the supposed innocence of the future generation. Nowhere to be seen is the urgency conveyed in the original Avatar, a film which successfully replaces the tired call to “think of the children” with the more pressing plea to “think of ourselves”.

Once the complexities of characterisation, motivation and difference are stripped from the world of Pandora, one is left with The Way of Water – a sequel so boring it had critic Mark Kermode coming up with alternative titles in order to entertain himself during the premier. My favourite? “Avasleep: The Way of Torture”.

the FILM dIspatch / page 37

FEATURE

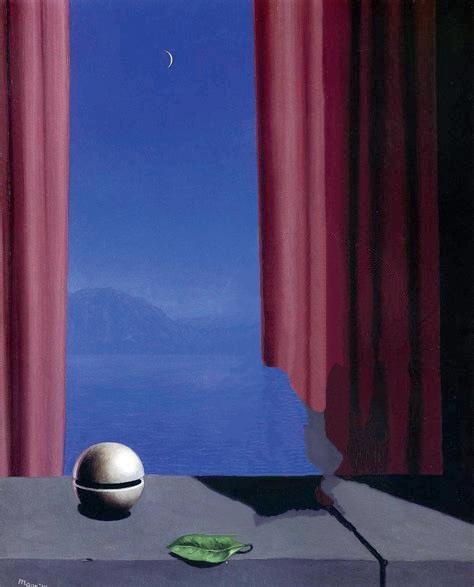

re-MeMBerIng the sutures In hIrosh (1959)

by Lim Kai

by Lim Kai

memory page 38 /

other: MneMonIc roshIMa, Mon aMour (1959)

the FILM dIspatch / page 39

Kai Tjoon

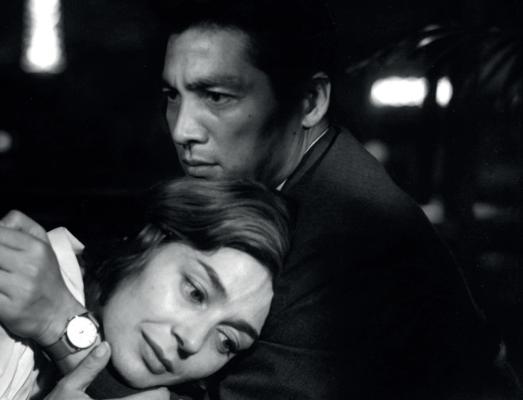

Lim Kai Tjoon analyses how in Hiroshima, Mon Amour, the past is not always an inaccessible aspect of our lives but an embodied experience in the present.

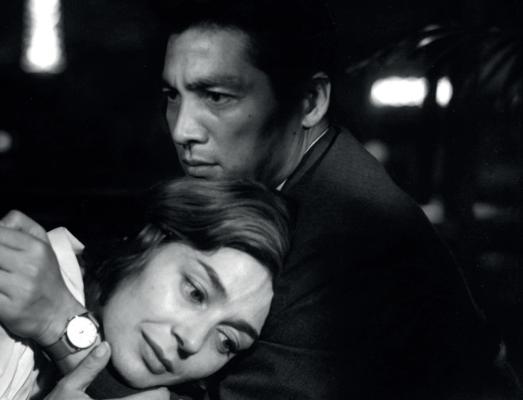

Hiroshima, Mon Amour is a film saturated with the impossibility of perfect remembrance. Memory is illustrated as fractured, refracted, and contentious through the two unnamed characters, ‘He’ (a Japanese man) and ‘She’ (a Frenchwoman), in their brief affair that temporally dredges up more than sixteen years of her unresolved past. Over the course of about twenty-four hours, ‘He’ and ‘She’ explore the traces of personal and collective traumas in an embodied erotics of history. Often confluent, these memories pose important questions regarding the ethico-political relationship between loving and knowing. As I will argue, this relationship has, at least in the film, produced antagonistic effects. Loving is often accompanied by a desire to come to know the Other, which constitutes an ideological approach that seeks to master and overcome the unknown beloved. This circumscribes the lover and his beloved in an unequal power dynamic that is experienced, among others, along gendered lines especially since ‘She’ lacks access to the male character’s own memories beyond the odd comment about his occupation and marriage. Here, it is arguable that knowing is codified as a masculine prerogative while being known disempowers the feminine as an object of knowledge. To love the Other then becomes a confronta-

tion of the Other, and one’s claim to knowledge is a collision between two subjectivities vying for control over the right to know. Yet, in Hiroshima, Mon Amour, ‘She’ manages to find an alternative outcome that resists this quality of negation in an antagonistic relationship with him––the right to self-knowledge and determination by emphasising the imperfect sutures of her forgetting.

Hiroshima, Mon Amour’s opening scene foregrounds a jarring distortion of memory that parallels the male character’s attempts to dispute her alleged recollections of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. During sex, through visual and haptic means, they perform a temporal disjointedness that seems emblematic of a lack of total access to the Other’s history. Prefaced as “reconstitutions” in the original French script, the couple puts on display an almost illicit erotics of historical trauma that seem to undergird and gestate the hidden bodily intimacies in the museum exhibits of war. Resembling the couple’s exchange, the museum is a space that actively represses memory even as its displays simultaneously evoke the past. The temporal distortions of the film are also dramatically heightened by the asynchronous music and its accelerating cadence in which shots between buried bodies glistening with debris, presumably in the throes of death, and the couple’s embraced sweaty forms alternate, in turn reflecting their conflicting assertions of memory. Sex, that is, the erotics of haptic apprehension, thus becomes a negotiation of power that re-members (historical)

memory page

/

40

trauma through pleasure.

I take a brief detour to montage theory. In conceptualising its ontology, Sergei Eisenstein argues that “the collision between two shots that are independent of one another” serves as a metaphor for the dialectical synthesis of meaning (26, my italics). Exploring the colliding elements within a shot is also necessary for the shock factor to deliver the film’s ideological message. This message is, as I have argued, grounded in gendered relations of power in the film. After sex, ‘She’ comments that “like you, I am endowed with memory”. The provision of memory is an effect of collision. The collisions between shots, bodies, speech, and time grate against scenes of love and death, Self and Other, and signal the intended contrapuntal effect of the film. ‘She’ mentions walking through the museum, which is also a space of reconstitution that attempts to contain the fluidity of time through curated exhibitions and knowledge. It is arguably a compartmentalisation of history that parallels the man’s efforts to contain and subsequently invalidate her knowledge of the past. Collisions are also present in the museum’s conceptual space: between knowing/not knowing and the objec-

tive real/the curated truth. Similarly, her visual perception of the exhibits re-creates the conflicting historicities that collide with his contestations of her memory through visual means. As sight is a process heavily associated with the masculine, her usurpation of the visual is curtailed by his counterclaims of her nothingness-to-see. Since the desire to know the Other is precipitated through this antagonistic, loving relationship, the confrontation between ‘He’ and ‘She’ mimics the museum’s conflicting nature, and his negation of her knowledge is a postulation of masculine power that he seeks to preserve.

A curious nuance to the couple’s initial dynamic emerges here: ‘He’ is not able to access Hiroshima’s past because he could not have been present while ‘She’ possesses this impossible possibility of stitching together––of re-membering––the fractured strands of the visceral past. This nuance is perhaps the reason for inducing (and deferring) in him a consuming desire for her. As the feminist philosopher Judith Butler writes, “desire transfigured through projection gives rise to the idealized contour or morphology of the body” (372). This idealised mould of his beloved is what fascinates the man intensely because it is the form which he has complete access to and mastery over. As ‘She’ has initially claimed knowledge of Hiroshima, a knowledge that even ‘He’ does not possess, he desires to rebalance that unsettled dynamic by fitting her memories within this idealised morphology.

Unlike the male lover who clings

the FILM dIspatch / page 41

“The collisions between shots, bodies, speech, and time grate against scenes of love and death, Self and Other, and signal the intended contrapuntal effect of the film”

to a position of power over his beloved, ‘She’ breaks through her disempowerment to reclaim the right to self-determination through knowledge. Love, for the female character in Hiroshima, Mon Amour, means opening herself to self-knowledge by coming to terms with her fractured and traumatic past. When ‘She’ acknowledges her past together with her Japanese lover, she does not, like him, indulge in a process of retaining power over the Other through exclusion. Cathy Caruth suggests that “history, like trauma, is never simply one’s own, that history is precisely the way we are implicated in each other’s trauma” (24). This intimacy of historical/personal trauma means that ‘He’ is also implicated to bear witness to her trauma in a similar way that ‘She’ has initially viewed his personal-turned-collective trauma of Hiroshima during sex, though he actively denies her that knowledge. Caruth further argues that in the film, “the act of seeing, in the very establishing of a bodily referent, erases […] the reality of an event. Within the insistent grammar of sight, the man suggests the body erases the event of its own death” (29). In a psychoanalytical vein following Freud, what Caruth suggests here is that trauma involves a simultaneous return to, and disengagement with, the repressed past––a dis/collision of temporal positionalities. If his sight is effected as an erasure of her memory, then ‘She’ is able to negotiate her Japanese lover’s annulling sight by re-experiencing her traumatic past with and through him. Her embodied performance of

these memories draws attention to the fractures of imperfect recall that liberate her, at one point causing him to admit that he will “remember [her] as the symbol of forgetfulness” and to “think of this story as the horror of forgetting”, referring to both the experience of war in Hiroshima and the warring tensions in one’s incapability of fully knowing one’s history.

Pivoting back to the tactile motif, ‘She’ becomes in touch with herself and her lover. When she recounts her descent into madness at the café, self-knowledge seems to be reconstituted partly from grasping herself and partly from embracing him at different intervals. In this case, both their bodies become texts; they become in-

memory page 42 /

tertextual. The way she ‘reads’ her past trauma through touch is not predicated on a return to an insular existence, but rather involving his shared participation as her dead German lover in Nevers. Consequently, this intertextuality that ‘She’ espouses reflects the transversal fluidity of knowledge and love across time. Unlike him, her history is not simply fixed in the past and intransigent or inaccessible. It is also an embodied performance within her present moment as a temporal drag to the past. When ‘She’ allows another to bear witness to her trauma, however fractured, she successfully reclaims autonomy over her life knowing that she has purposefully, intimately, and erotically opened herself to herself

through her collision with the Other. Borrowing Duras’s words, ‘She’ “carries within her, with her, this vague yearning that marks a reprieved person faced with a unique chance to determine her own fate” (111). And this future oriented determination will always be re-membered by her imperfect sutures of forgetting––of finally “consigning” her conflicting past to oblivion.

the FILM dIspatch / page 43

Cited

1. Butler, Judith. “Desire.” Critical Terms for Literary Study, ed. Frank Lentricchia Thomas

2. Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experi-

ence: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2007.

3. Duras, Marguerite. Hiroshima Mon Amour. Grove Press, 1961.

4. Eisenstein, Sergei. “The Dramatur-

memory page 44 /

gy of Film Form [The Dialectical Approach to Film Form]”. Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. 8th ed., edited by Braudy, Leo, and Marshall Cohen. New York: Ox-

ford University Press, 2016, pp. 23–40.

5. Resnais, Alain, director. Hiroshima, Mon Amour. Zenith International Film Corp., 1959.

the FILM dIspatch / page 45

FEATURE

FuorI

memory page 46 /

by Irene Ross

the FILM dIspatch / page 47 prograMMa

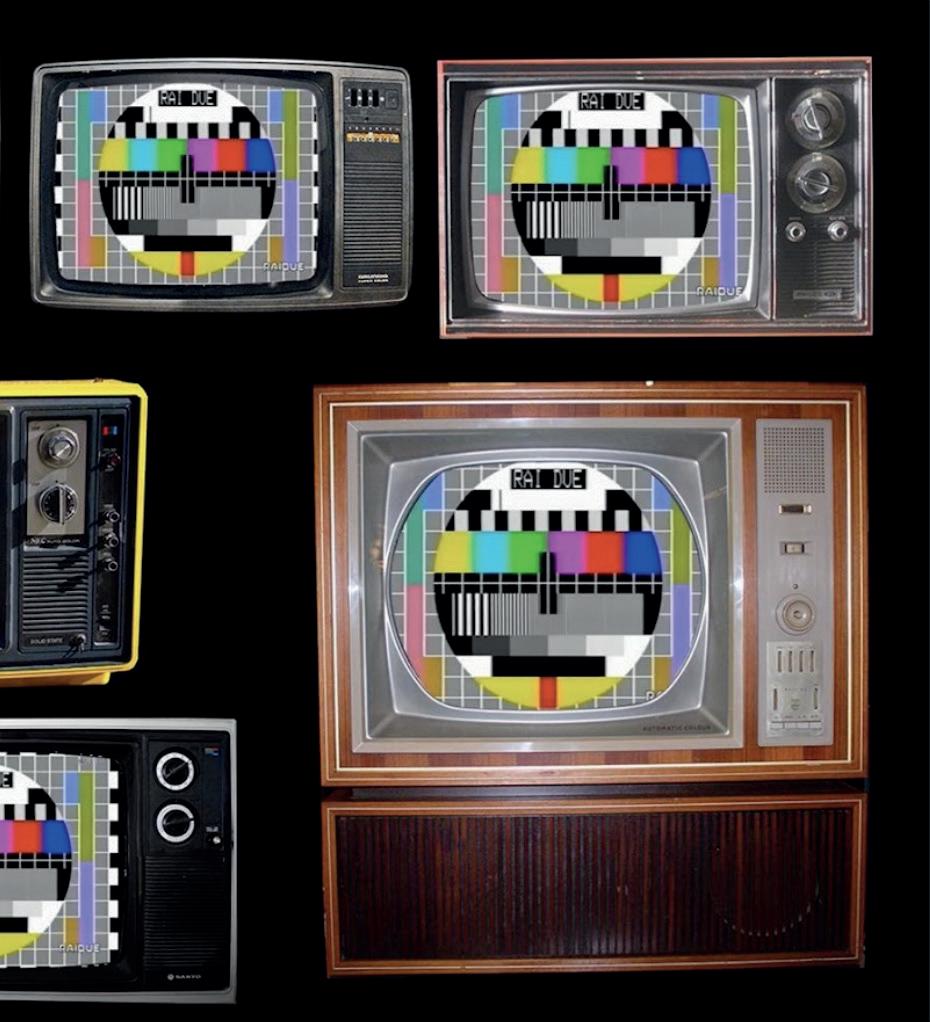

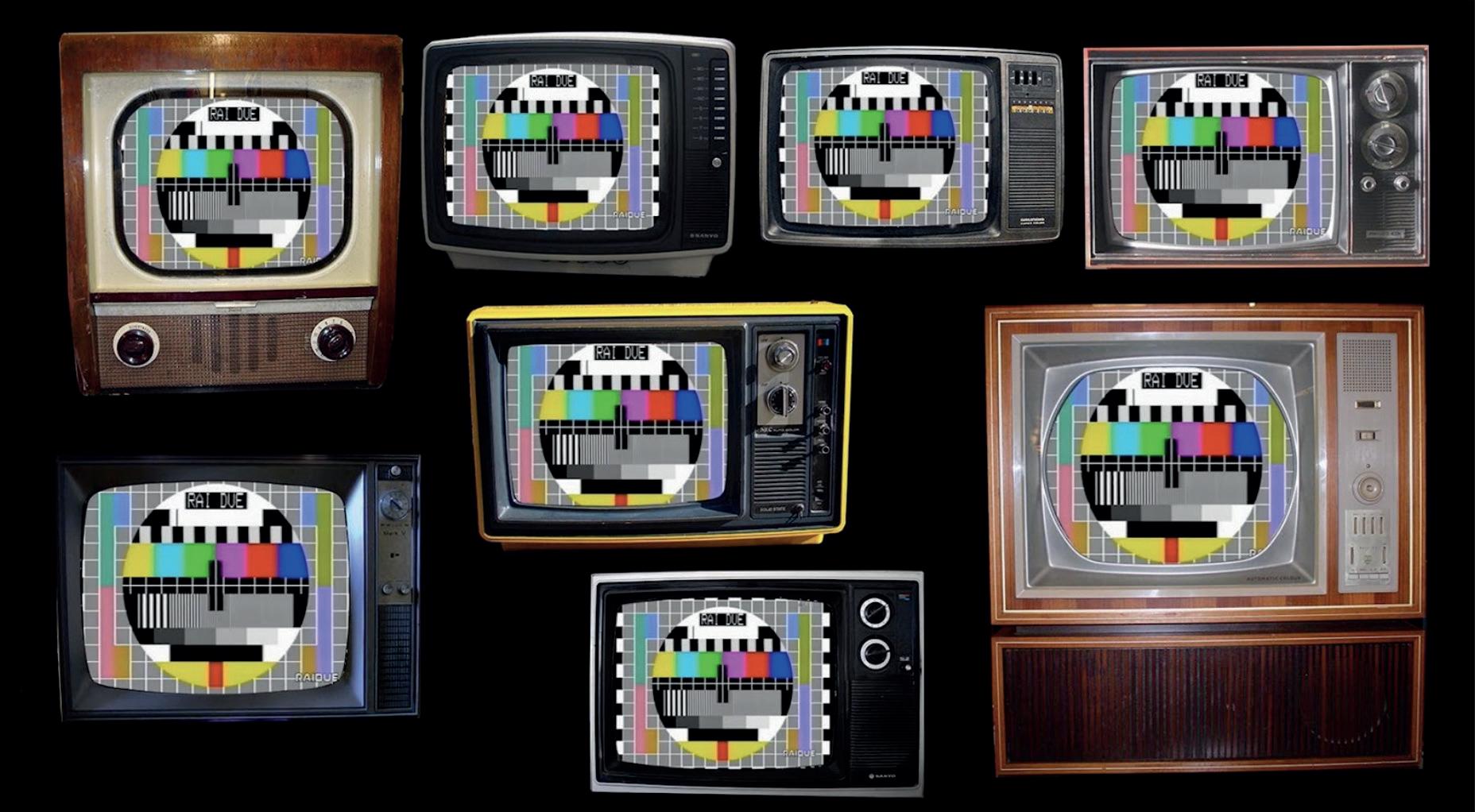

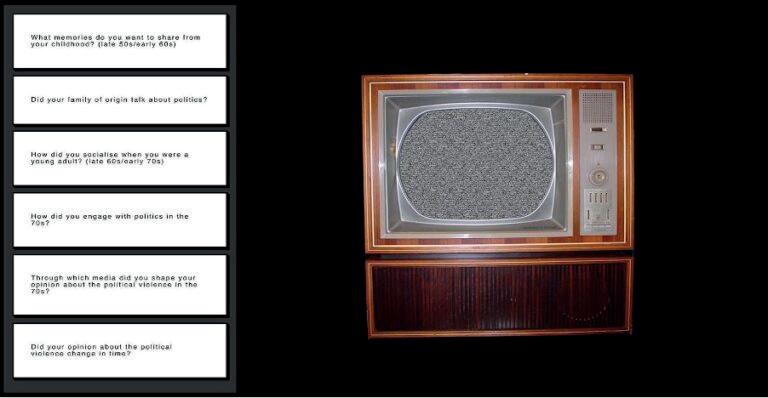

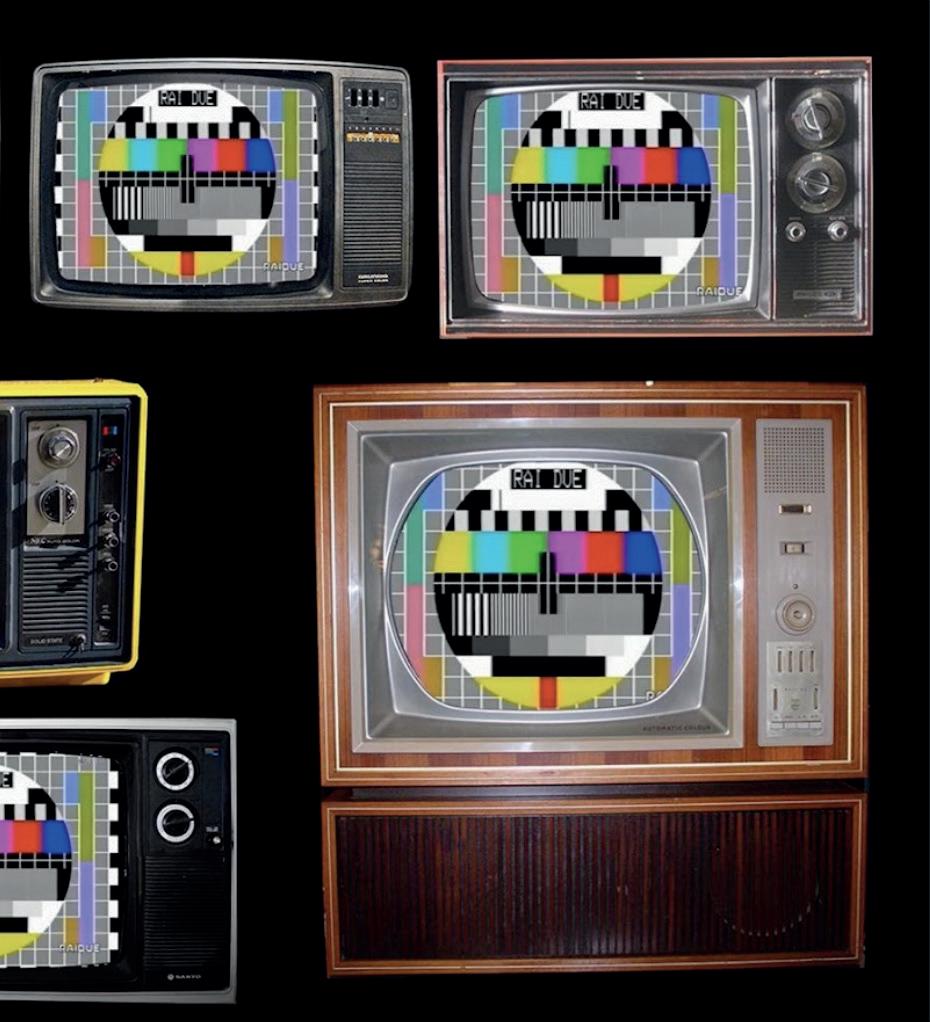

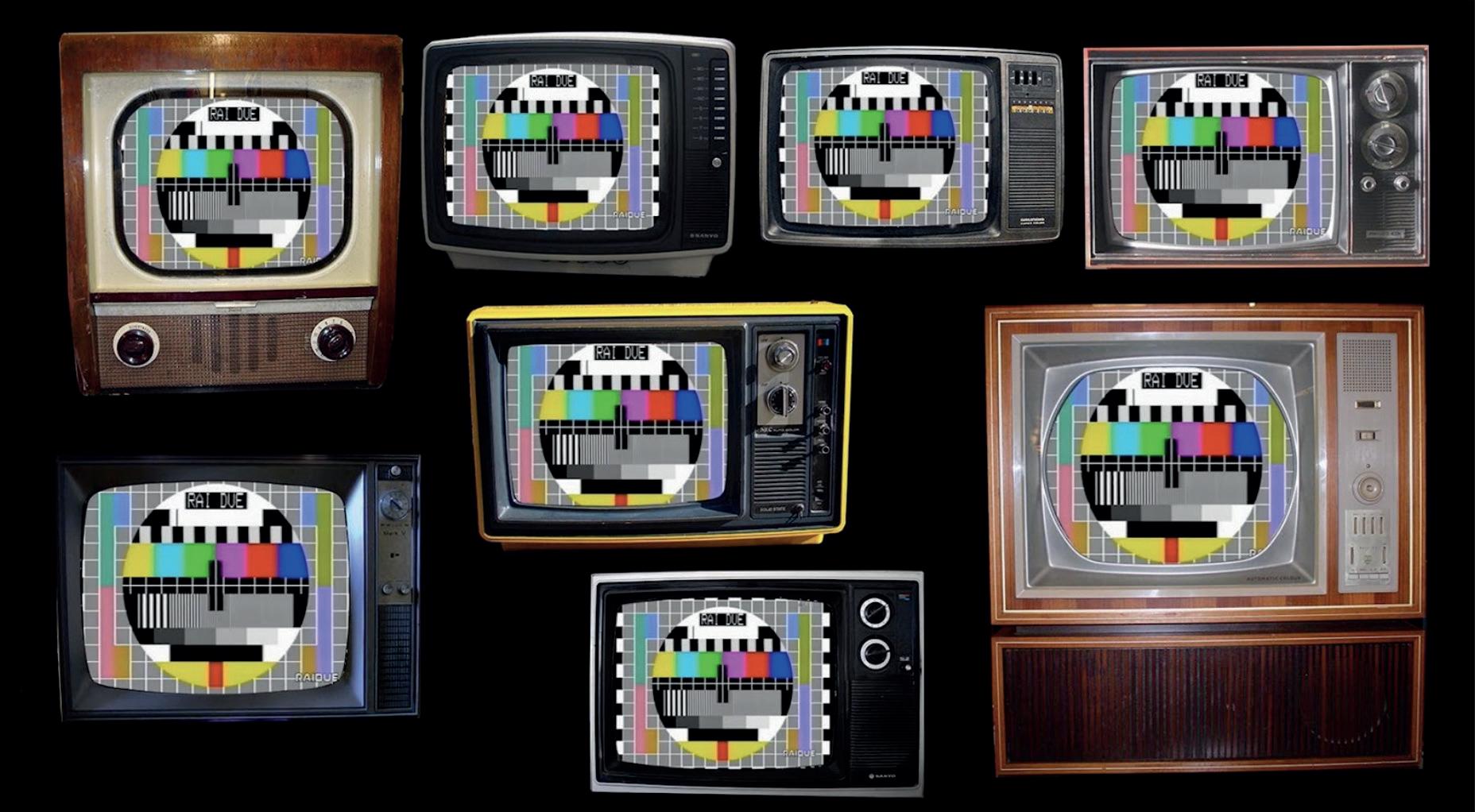

In their short film Fuori Programma, PhD student Irene Ros looks at the collective memory of Italian right-wing political violence (1969-1980) through interviews with Italian women who were young adults at the time.

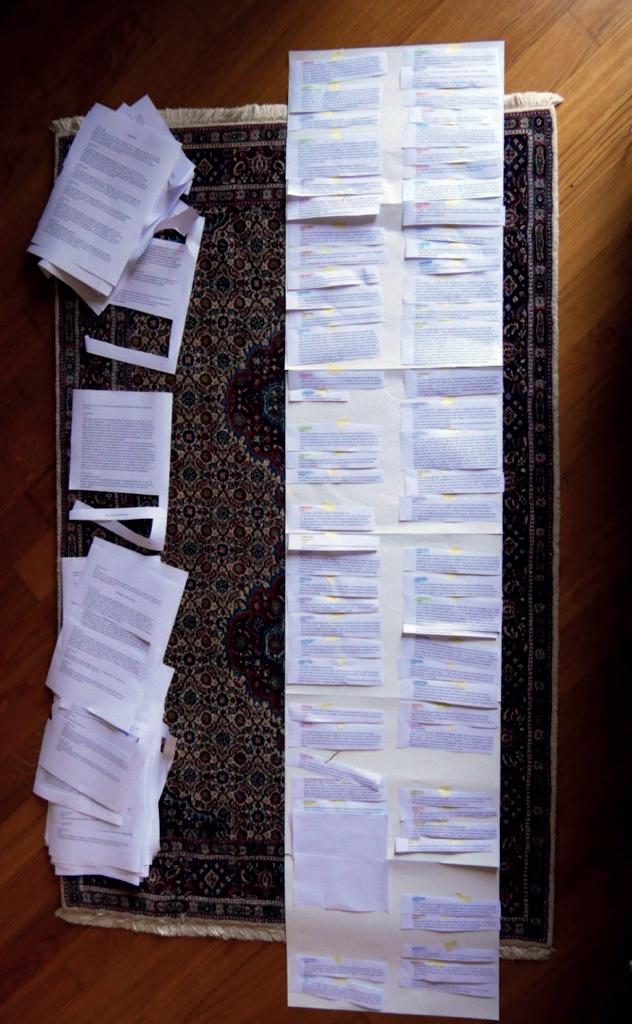

Fuori Programma [Unscheduled or Off Plan] is a short experimental documentary film, that edits together the memories of the first nine participants of the SGSAH-funded PhD project ‘Performing Stragismo and Counter-spectacularisation: Italian right-wing Terrorism and Its Legacies’. The project investigates the divided collective memory of the Italian right-wing terrorist attacks (19691980), through the under-represented narratives of Italian women who were young adults in the Seventies, and who belonged to the majority of the population, (i.e., people who were not involved in political violence).

Academic research on Italian terrorism usually engages with the main actors of these events, namely: the victims, their families, and the former terrorists. Furthermore, the media’s discourse about terrorism calls women into question only to play the role of victims (grieving mothers, wives, daughters), or sexually deviated former terrorists. My project intends to offer an alternative to the predominantly male-centred discourse.

My practice draws from Dwight Conquergood (2002), who defines the practice as “participatory epistemology” or “engaged knowledge” and builds on Phelan’s (1996) distinction

between marked and unmarked:

“As Lacanian and Derridean deconstruction have demonstrated, the epistemological, psychic, and political binaries of Western metaphysics create distinctions and evaluations across two terms. One term of the binary is marked with value, the other is unmarked. The male is marked with value; the female is unmarked, lacking measured value and meaning”

(Phelan 1996, 5)

I argue that, as a result of the binary division that characterises Western knowledge, oral history is a domain that pertains to the feminine, in contrast to the written page. My project employs oral history as a methodology; the conversations were designed as semi-structured interviews, and this flexibility allowed me to take into consideration the participants’ need to feel listened to and to connect (the conversations with the participants started in February 2021, when Italy was going through a Covid-19 lockdown), and at the same time to develop a methodology that aimed at the co-creation of knowledge. The semi-structured interviews proved to be the right choice when, during the conversations, I realised how the collective memory of the right-wing attacks was not only divided but lacking and often erased. Through this method, I could collect broader points of view about the 1970s and question what memories ‘over-wrote’ those of the right-wing bombing attacks. Each participant sat through three one-hour meetings: the first fo-

memory page 48 /

cused on their background, revealing the relationship of their family of origin to the legacy of the Second World War, as well as their childhood, youth and adulthood. The second unravelled from an object that they were invited to bring in, as a memento of their lives in the 1970s. From the object and the memories connected to it, I encouraged them to identify some starting points (characters and events) to narrate life in Italy in the 1970s. Each participant unfolded the narration differently, some entangled their personal stories with historical events, whereas others outlined a more conventional narration of the historical facts or merely described those years only through personal memories.

In the third conversation, the daughters or sons were invited to join, and I addressed some of the same questions I asked the women to their children (Did you talk about politics in your family? Were people profiled according to their political beliefs?), exploring the recurrent patterns linking how politics was discussed in their family to the way in which they talked about it to their children.

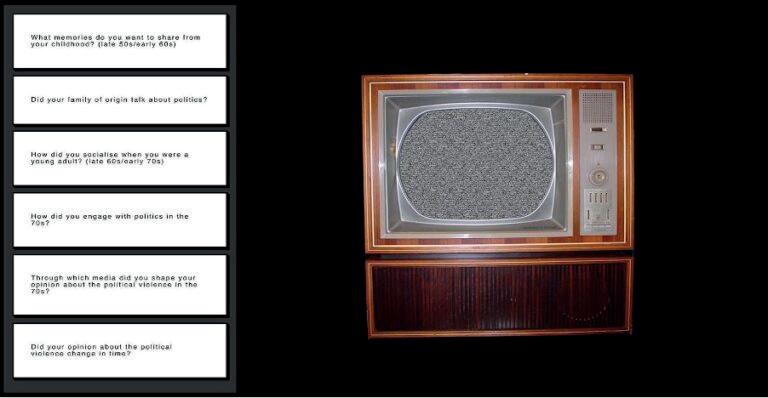

The shape and content of the film

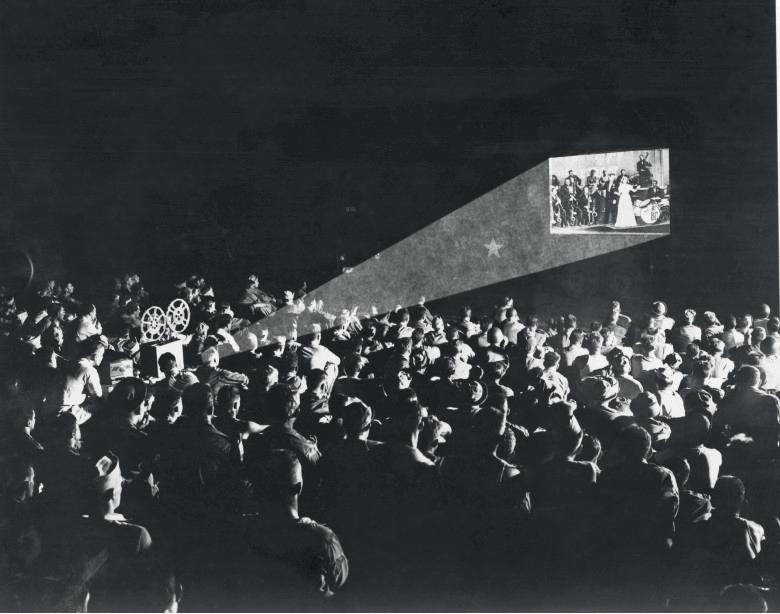

were informed by the participants: the aesthetics sprang out from the first conversation I had with the first participant (Figure 01) and accompanied me throughout the creation. While talking about her childhood, the participant mentioned the social impact of owning a tv at the end of the 1950s, explaining how her family home’s garden became a sort of community centre when some tv programmes were broadcasted.

“I remember that we had, at one point… we were the only ones with a television – you know there were those famous tv shows – so they came in the summer… we put the tv near the window and the courtyard – it looks like a movie but it was like this – it was full: about fifteen, twenty people with their chairs to watch the tv with us.”

Participant A, 25 February 2021

Initially the centre of social gatherings, televisions became the main source of any memory about the right-wing bombing attacks, and as a result I decided to visually highlight their relevance, yet at the same time create a sense of subversion. Moving the participants to the foreground (each framed by an old

the FILM dIspatch / page 49

Figure 1: frame from the film Fuori Programma

“The aesthetics challenge the concept of ‘political subject’ ”

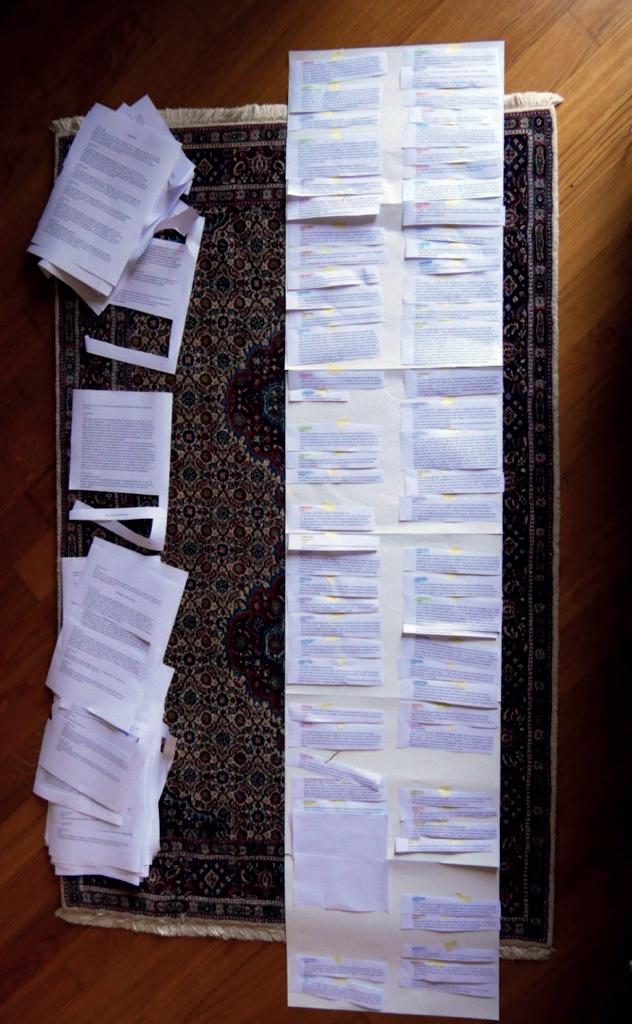

television) and everything else to the background (footage showing the aftermath of the attacks), the aesthetics challenge the concept of ‘political subject’ and represent (or, better, create a space to self-represent) the participants as such. Through the televisions’ “vintage vibe”, the low quality of the videos finds its reason for being. The dialogue emerged from comparing the transcriptions: the sen-

tences I found more interesting, or that resonated with those of other participants, were copied into a document, with a different colour assigned to each participant, to give equal representation to everyone (Figure 2).

Editing all of the memories together, I could, on the one hand, begin to theorise a difference between spectacular and memorable. On the other hand, I could identify a pattern amongst the memories that overwrote those of the right-wing terrorist attacks. Although the participants’ fathers were the ones experiencing the spectacularity of the Second World War (as fascist soldiers or as partisans), they often did not talk much about their experience. Instead, the mothers and the women in the family were the ones talking about the everyday life during the war. Similarly, the spectacularity of right-wing terrorism was carried through the images of the news, but often the participants could not find connections between these spectacular images and their personal stories, whereas their embodied memories of every day were the ones

memory page 50 /

Figure 2: dialogue from the participants

they wanted to talk about. During the Seventies, women were not only threatened by the rightwing attacks as citizens, but also (more or less consciously) by the fascist ideology as women. This second threat felt more urgent and pressing, involving the women’s bodies directly, and was not only expressed by violent episodes (such as the bombing attacks, but also group rapes like the infamous one perpetrated against theatre maker Franca Rame), but by a creeping culture that was not ostracised and antagonised by Italy’s unofficial state religion, Catholicism, which on gender-related issues was on the same side as the right-wing militants, against divorce and abortion. If, as Foucault (1989) theorises, history is the unravelling of forces driven by individual bodies, it seems fair enough that the participants over-wrote the memories of the right-wing political violence with those that embodied their response to this violence, and performed new ways to be women, where gender performativity is understood as “a repetition and a ritual, which achieves its effects through its naturalization in the context of a body” (Butler 2006, 203).

In the film, these overwritten memories were edited to remark on the conscious and unconscious con-

nections with the main topic of my research. Although this is more evident in the second outcome of my research (figure 04) (an installation including five tablets from which some of the newer participants answered some questions, giving the audience an interview-like experience), in Fuori Programma, the process of creation is exposed. The dialogue results from assembling different conversations, laying bare in front of the audience the incompleteness and partiality of the material which they can ultimately see. Furthermore, the cuts reveal the power structure, and encourage a reflection on agency in participatory practices.

Even though the participants were subject to what Loughran, Mahoney and Payling describe as the “online disinhibition effect” (Oral History, Spring 2022, Vol.50), they were

aware of being recorded, and hence were, to different degrees, performing themselves. However, I shaped their visibility as political subjects, based on what I determined to be representable, but also relatable.

The participants’ virtual pres-

the FILM dIspatch / page 51

Figure 3: frame from the interactive installation Siamo in Linea

ence gives the audience the sensation of authenticity and truth-telling, similar to what happens in many testimonial theatre plays, in which the presence of the witnesses is at the centre of the work. In her Performing the Testimonial: Rethinking Verbatim Dramaturgies, Amanda Stuart Fisher asserts:

“The discourses of authenticity associated with verbatim theatre tend to circulate around two interconnecting ‘promises’ that disclose different kinds of truth claims.”

(Stuart Fisher 2020, 81)

The two promises are first to show the audience a source of truth and, second, the sincerity of the personal narratives. These claims do not consider the possibility of faulty and altered (i.e. performed) memories, which could be mitigated if they are put in conversation with original documents, a strategy I only partially employed in the Fuori Programma. Recognising the memories’ limitations, and still wishing to work with under-represented subjects, I have often been questioning: what constitutes a legitimate historical truth?

During the SGSSS-SGSAH-funded Symposium Doing Feminist Research (4-6 May 2022, Edinburgh),

Rashné Limki suggested, “It is better to do good work than legitimate work”. Without disavowing the existence of historical truth, I hope his project will allow me to do some good work. I am currently employing the participants’ memories in creating a live performance; this will enable me to include controversial memories not included in Fuori Programma, giving them context. Since the participants’ stronger memories originated from a physical engagement with the senses, I wish to offer the audience the gift of presence and to re-present memories through the ephemerality of the performance. Fuori Programma has been presented so far during a Being Human café at the Scottish Oral History Society in Glasgow (November 2021, as well as at the Connect-Fest at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Glasgow (June 2022), and at the Davamot Symposium in Sweden (December 2022).

Fuori Programma, the live performance, will take place on Tuesday, 28 March, at 7 pm, at The Pleasance Theatre, Edinburgh.

Fuori Programma can also be found on YouTube.

memory page 52 /

“I wish to offer the audience the gift of presence and to re-present memories through the ephemerality of the performance”

Cited:

1. Amanda Fisher Stuart. 2020. Performing the Testimonial: Rethinking Verbatim Dramaturgies. Manchester: Manchester University Press

2. Dwight Conquergood. 2002. ‘Performance Studies. Interventions and Radical Research’ in The Drama Review, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp. 145-156

3. Guy Debord. 1990. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. London and New York: Verso

4. Guy Debord. 2014 [1967]. The Society of the Spectacle. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets

5. John Foot. 2009. Italy’s Divided Memory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

6. Judith Butler. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge

7. Judith Butler. 2011. Bodies that matter. Routledge (PDF)

8. Michel Foucault. 1989 [1966]. Order of Things. London and New York: Routledge

9. Michel Foucault. 2000. Power. New York: New Press.

10. Peggy Phelan. 1996. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London, New York: Routledge

11. Ruth Glynn. 2013. Women, Terrorism, and Trauma in Italian Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

12. Tracey Loughran, Kate Mahoney, Daisy Payling. 2022. ‘Reflections on remote interviewing in a pandemic: negotiating participant and researcher emotions’ in Oral History, Spring 2022, Vol.50

the FILM dIspatch / page 53

FEATURE

memory page 54 /

reMeMBerIng oLd hoLLywood: MeMory In once upon a tIMe In hoLLywood (2019)

by Grace LaNasa