5 minute read

Promised gifts

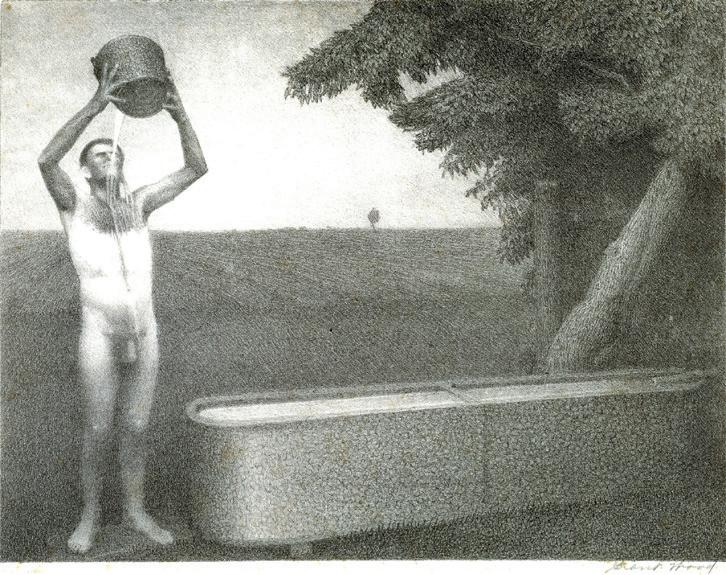

Grant Wood, Sultry Night, 1939, lithograph on paper. Image: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Park and Phyllis Rinard in honor of Nan Wood Graham, 1994.115.4 © 2021 Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/ Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

—Allison Slaby, curator

Advertisement

Reynolda has been offered a promised gift of a complete set of Grant Wood’s lithographs. Wood, the creator of Reynolda’s iconic 1936 painting Spring Turning, made the lithographs for the Associated American Artists in New York. Wood’s consummate drafting skills made him a natural for the medium and ultimately he produced nineteen lithographs, about a quarter of his mature work. The AAA produced the lithographs in editions of 250 and sold them for $5 each. The opportunity to create affordable art during the Great Depression appealed to Wood.

Many of the lithographs depict the familiar agrarian subjects common in Wood’s paintings. In Seed Time and Harvest, a man strides across a farmyard carrying a bushel of corn, while rows of corn hang under the eaves of the corn crib behind him. January captures deep drifts of snow blanketing the ground and covering the corn shocks on a frozen winter day. In July Fifteenth, rolling hills are divided into rectangular plowed fields. Farm buildings and stylized trees are viewed from a bird’s-eye perspective. In In the Spring, Farmer Planting Fence Posts, a farmer stands on a rise at the edge of a field. His figure dominates the landscape; he towers over the horizon line that cuts across the middle of the image.

But Wood also experimented with the subjects of his lithographs. His work in the prints extended to narrative subjects (Sultry Night, Honorary Degree, Shrine Quartet, The Midnight Alarm) and still lifes. The colored still life lithographs of fruits, vegetables, and flowers were unusual in Wood’s oeuvre. They represent the fecundity of Iowa’s farmland. Wood sent the prints to his sister, Nan, and her husband for them to add watercolor by hand as a way of supplementing their income during the Depression. These prints sold for $10 each rather than $5.

Sultry Night was controversial in Wood’s series of lithographs. Because it depicts a nude male figure, the Postal Service declared the print obscene and refused to send it through the mail. The AAA thus could not distribute this print as it did copies of Wood’s other lithographs and made the decision to limit the print-run to 100 instead of the customary 250, making it both rare and valuable.

A private collector in Winston-Salem has, over time, made a concerted effort to collect the best impressions she could obtain. As a result, this is a remarkably fine set of Wood’s lithographs. This promised gift to Reynolda is especially fitting given the importance of Spring Turning to the collection.

A Collaboration to Create The Voyage of Life

—Genie Carr, docent-volunteer

Each of us travels a lifelong journey of ages and stages, gathering joys, pains, people, and places to remember. In 2020, the pandemic tossed many travelers onto new paths and generated rearranged thinking and unaccustomed ways of working.

This was true of Reynolda House, too. This summer and fall, works from the Wake Forest University art collections and Wake’s Lam Museum of Anthropology have joined Reynolda’s works in the Babcock Wing gallery. That means that four curators worked on the exhibition: Phil Archer, deputy director, Reynolda House; Allison Slaby, curator, Reynolda House; Jennifer Finkel, Ph.D., Acquavella Curator of Collections, Wake Forest University; and Andrew Gurstelle, Ph.D., Academic Director, Lam Museum of Anthropology, Wake Forest University.

Phil came up with the exhibition idea last year when the Museum needed to find something to replace a traveling exhibition that had been slated for summer and fall of 2021.

Phil said that several thoughts surfaced when considering a new exhibition: a survey of Reynolda’s collection had not been done recently; the pandemic “offered an opportunity for empathy through art, a look at our parallel journeys”; each of us is on a “voyage of life”; and, not least, that Wake Forest University had some excellent collections whose works had rarely been shown in Reynolda’s galleries.

Phil and Allison talked about using Thomas Cole’s The Voyage of Life series as a base for the exhibition, with the river as a metaphor for the stages of life.

Opposite and this page: Detail. Thomas Cole, engraved by James Smillie, TheVoyage of Life: Youth (1854–55), engraving, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Gift of Barbara B. Millhouse

Allison said, “We knew we wanted to work with the collections at Wake,” so Phil called colleagues Jennifer Finkel and Andrew Gustelle. Both of them were delighted to join in the effort. Although works in their collections had been shown in collaboration with some Reynolda exhibitions, they had rarely hung in gallery spaces at Reynolda; there were some wonderful things to show.

Given the nature of anthropology, Andrew had fewer items to offer, but contributed a colorful indigenous Diné (Navajo) cradleboard, an Inuit spirit mask, and dance fans used by Yup’ik people of Alaska during a winter ceremony that calls the spirits of game animals to return for the community’s nourishment.

Jennifer had many choices, including an important painting that has been seen by few people: Albert Bierstadt’s Niagara, which has hung in the university president’s house for sixteen years. Twelve works of American art from Wake’s art collections (which have 2,000 items among them) are borrowed for the exhibition. Jennifer appreciates how the pieces from the three institutions “are in dialogue with each other. We want to keep this collaboration going.”

The collaboration doesn’t end with art collections. Reynolda team members Amber Albert, Julia Hood, and Beth Hoover-DeBerry collected a sampling of important life moments from the community, and some of those memories are shown on the walls in the gallery.

The pandemic may have disrupted lives, but, at Reynolda, curators and others worked together to show life in different regions, years, races, and seasons for the learning and enjoyment of others.