6 minute read

Solid and Valuable as a Brick of Gold

from ONA 93

By Alan Castree (53-61)

John Forster (1820-28) was a Northumbrian of note. He made a unique contribution to the work and life of Charles Dickens and recorded that from 1837 onwards, ‘…there was nothing written by him which I did not see before the world did, either in manuscript or proofs.’

Advertisement

Born within two months of Charles Dickens, in April 1812, John Forster has not figured much in the public’s imagination, even amid the many celebrations of the bicentenary of Dickens’ birth two years ago. At the time of Forster’s death, in 1876, there was much grief among those who knew him well, but little public recognition and yet it was he who had written an outstanding biography of Dickens, after the latter’s death in 1870. Margaret Drabble refers to the three volume work as establishing Forster as the first professional biographer of the nineteenth century.

The Forster family were Northumbrians and their faith was Unitarian. John’s father, Robert and his uncle, John, were both cattle dealers and butchers in Newcastle. Robert married Mary, daughter of a Gallowgate cow keeper and described as “a gem of a woman”; they had four children, John junior being the second. The family were not well off but Uncle John, “Gentleman John”, remained single and became prosperous; he paid for his nephew to go to the RGS, from 1820 to 1828 (where he was Head Boy) and also for much of his later education.

Forster excelled in both the classics and the newly introduced subject of Mathematics. He loved the theatre and must have cultivated good contacts as in 1828 the Theatre Royal, Newcastle, staged one of his plays. In the same year he left RGS to enter Jesus College, Cambridge, but after only a month he moved to London to enrol at Inner Temple for the Bar and begin his Law studies at University College (UCL). This was a new university, with a strong Unitarian element in its founding. UCL was innovative in higher education in seeking to link practice to theory. Forster felt comfortable both in his studies and his religious beliefs in these surroundings.

In 1832, having shown outstanding legal talent, he dismayed his tutor, Thomas Chitty, a prominent special pleader, by abandoning pursuit of a career in law in order to follow his literary inclinations. We do not know what Uncle John thought of this but Forster’s biographer, JA Davies, opines that ‘…his family must have thought him mad or close to it.’

It was a bold step to leave a promising calling as a lawyer; the literary world in 1830s London had little to commend it. However, seen now from afar, the literary world was on the cusp of a revolution, of which John Forster became an integral part.

Literature was the beneficiary of the rapid expansion of literacy among the British population and of the acceleration in the improvement in printing technology. Writers could sense the potential for wider readership and the greater likelihood of recognition as professionals in their chosen field. Forster was to play a major role in these advancements. He became a frequent contributor to trenchant periodicals as a drama and literary critic and his contributions to The Examiner (of which he later became editor) led to him being noticed among the literati.

Dickens was already an accomplished journalist and author when the two men met.

He saw in Forster a friend upon whom he could rely not only for the oversight of the layout and shape of his scripts but also for his ideas on literary style and what appealed to the public. We shall see, however, that they did not always agree on moral tone, which, in Forster’s case, was unbending, leading to Dickens lampooning him in his novels.

Dickens also looked to Forster to fight his battles with publishers; Forster drew upon his formidable legal skills and powers of persuasion to get the best deals for Dickens and for the literary world in general. He became Dickens’ guide and adviser in all aspects of his literary and personal life. He helped Dickens in the painful arrangements regarding separation from his wife, Catherine, and was an executor to his will.

He wrote for Dickens’ Daily News, becoming its editor and for the writer’s Household Words. He established himself in a wide literary circle. Elizabeth Gaskell, whose father was from the North East and who married a prominent Unitarian minister, became a close friend. Dickens invited him to frequent family gatherings in his own home to ease his isolation from his distant relatives; when Forster’s brother died unexpectedly, Dickens offered himself as a surrogate, “…you do have a brother left, one bound by ties as strong as ever nature forged”, which must have given Forster considerable comfort.

Forster had a short love affair with the poet, Letitia Landon in 1833, but it ended unhappily and it was not until 1856 that he married. This was to Eliza Ann Colburn, wealthy widow of a publisher. It was a childless yet happy marriage and they lived in some style, in a house which they had built for themselves in Kensington. Before marriage he had been a very hospitable bachelor and convivial host; Dickens used Forster’s early accommodation at 58 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, in the legal heart of London, as the model for Tulkinghorn’s chambers in Bleak House.

Forster gave practical assistance to many writers, actors and stagers of plays. Thomas Hood, Elizabeth Gaskell, Tennyson, Longfellow and Robert Browning were all beneficiaries of his advice on literary style, praise in his literary reviews and introductions to publishers. Thomas Carlyle valued his fine combination of business nous and social skills. He supported Forster in his unremitting drive to earn writers the dignity and social acceptability which they both agreed were deserved. Bulwer Lytton described All who read Dickens know that he had a sharp eye for amusing characteristics in the folk around him and was not slow to introduce them to his novels. Forster did suffer some indignity in portrayals of himself, without, perhaps, being fully aware of the depth of the parody. Dickens noted that many of Forster’s early friends were much older than he was –Bulwer Lytton, Charles Macready (tragedian), Leigh Hunt and Charles Lamb. Each of these took the lonely young man from the north into their homes. Forster did project the solemn air of an older man and his fierce retention of his northern accent prompted some amusement among the sophisticates of the capital.

Dowler was Dickens’ first caricature of Forster, in Pickwick Papers: forbidding, intense, quick to anger but also quick to accord; grave and reflective but also swift to notice a friend in need and ready to offer personal comfort. It was a close likeness.

The second, more complex character was Podsnap, in Our Mutual Friend. Forster’s claim to possess a greater understanding of mid-Victorian readers than Dickens did and his attempts to impose a strict, moral tone upon the writer’s work inspired the idea.

Dickens bridled at some of Forster’s extreme views and found them stifling. Exasperated on such occasions, Dickens would seek the alternative company of unconventional and bohemian types, such as Wilkie Collins.

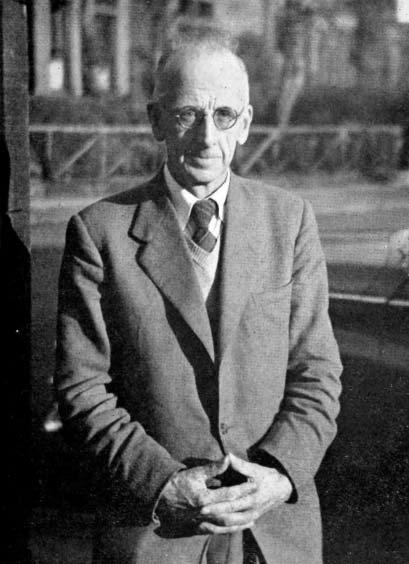

Top left: Charles Dickens , 1861 Below: Dowler, Dickens’ caricature of Forster in Pickwick Papers, 1836