8 minute read

ONA Now and Then

from ONA 93

It is, I suppose, an occupational hazard for school heads to be accused of boasting. After all, we’re employed to be the figurehead of, and leading advocate for, the school.

We’re expected to communicate our vision and ambition for the institution: we also have to spread a relentlessly positive message, praising the many triumphs and even (dare I admit it?) minimising the shortcomings.

Advertisement

Nonetheless I’m not being in any way self-congratulatory when I applaud the manner in which the ONA Magazine is currently going from strength to strength. It’s all thanks to you loyal Old Novocastrians who seem to be inspiring one another, from one edition to the next, to put pen to paper (or, at least, to hammer the word processor) and share your reminiscences of RGS past.

It’s healthy, too, to indulge in robust debate. On the next page J Harvey Smith (44-52) takes my ante-predecessor, Alister Cox (72-94), to task for suggesting that places won at Oxford and Cambridge are a crude measure of a school’s success, and that concentration on such statistics might appal rather than amuse. In a sense, both are right, of course. Smith rightly takes pride in the achievements of his period in the school: Cox inevitably occupies the same territory as I must nowadays, certainly taking delight in high academic achievement, including places won at Oxbridge, while appreciating that parents and students alike demand a broader range of what nowadays we too often term ‘outcomes’ from education.

That breadth differs little from the many pictures of the past painted in the following pages. There were no glittering prizes to be won by the boys who enjoyed O.T.C. camps in 1914: but they still took part, and made the most of them (as our boys and girls do to this day).

When I was a young teacher, 35 years ago and more, the Times Educational Supplement used to produce a schools’ league table of Oxbridge scholarships won: there were no other statistics available. As the computer age made such information ever easier to obtain the appetite grew for league tables: I’m never sure whether that was fuelled by the media, government or public interest.

First A Levels, then GCSEs and now a host of other measures are used in a variety of analyses to create league tables: initially by newspapers; next for government; and nowadays newspapers take the government’s figures in order to manipulate them and create their own different league tables! They create a particular form of madness that too easily drives schools into focussing entirely on those things that can be measured – to the detriment of ‘softer’ skills and activities. At the RGS we are both unlucky and fortunate. Unlucky because an academically selective school can have no hiding places: we do well in such league tables because our boys and girls achieve so highly, but the pressure is on to stay ‘up there’. But we are fortunate too because our students are both talented and hard-working, so that we can help them achieve those remarkable results while still pursuing energetically that huge range of sporting, artistic and cultural activities that have always characterised the RGS.

At the heart of it all, though, is that amazing experience of diverse people (yet, in a sense, with like minds) who enjoy great experiences at school and form lifelong friendships. It’s no surprise (but a delight) to me that ONs from many years ago still enjoy reunions. How good to see the Penrith group meet again (and vow to continue!)

Moreover, in September it was a joy to welcome the ‘class of 1944’ to celebrate almost to the day 70 years since they started at the RGS. We heads too swiftly assume that the course of the school is ever onward and upward, and that we must be doing so much better than all those years ago: but one of that group (I’m sorry I can’t remember who) reminded me that some things are timeless.

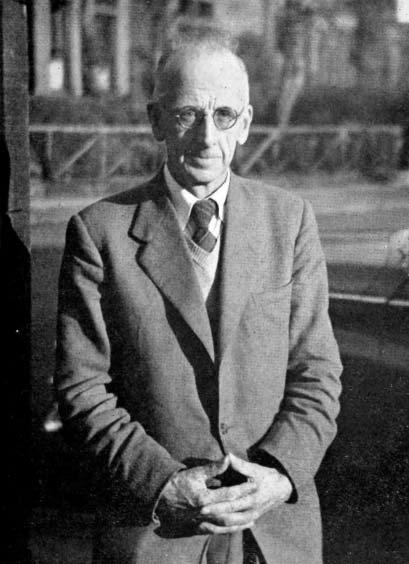

He recalled the advice given to him as an 11-year-old on his first day by the Headmaster, Mr Thomas (22-48). The most important thing the school could teach them, he stated, was “thoughtfulness for others”.

The RGS teaches a great many other things too, now as then: but if that were the primary lesson that the 11-year-olds who joined us last September take away from the school, I think I could be satisfied.

Bernard Trafford Headmaster

ONA Now and Then

Past and Future Learning

The Flyers, 1969

I am wondering why I feel so edgy about Alister Cox’s (72-94) ONA Now and Then article in the autumn ONA Magazine (see issue 92). And so, given also the request for nostalgia on Sammy Middlebrook (18-58), I am writing this to find out.

“Fancy a school’s academic reputation depending on the award of Oxbridge scholarships,” says the 1972-1994 Headmaster. When I was at the RGS from 1944 to 1952 you went up to Cambridge, down to Oxford (or vice-versa) and along to King’s. We had a healthy, politically incorrect sense of humour in those days. There were far, far fewer universities then –so what was so terrible and unnatural about judging academic reputation on Oxford and Cambridge scholarships? How the future denigrates the past, safe because it isn’t yet the past.

University entry was usually from a Third Year Sixth, when boys went the rounds of the college’s own exams searching less for a Scholarship, or even an Exhibition, than simply in the hope of being awarded a place as a commoner and getting a local government grant. So is the omission of places or of the other universities the academic reputation problem?

And what is this about Fliers/Flyers in the 60s? (“The Fliers had to fill out what was called 2.1”). In 1944 you started in 2.1, 2.2 or 2.3, presumably because it was thought that the more academically inclined would learn better together, which is not such a terrible idea either. There was a system of promotion and relegation where some pupils (not ‘students’) played the role of Fulham and hovered between 2.1 and 2.2. But so what? Either you understood the work or you didn’t. In 1944 there were also boys who were a year younger than others in the class, just as with the Fliers when they skipped the Remove. If ‘maturity’ was later a concern you could always do your two years’ National Service before university.

When it came to university there was no question of feeling “significantly unimpelled” to try for Oxford or Cambridge; if there was a chance, why would you not take it? I was saved from an academic discendo duces plunge in the Sixth when Higher School Certificate, which needed two major subjects and two subsidiaries, changed to a new system of three equivalent A Levels. But you can only play the side they put out against you.

It is the same for the past’s grandchildren, who are still wading through an ebb tide of coursework (which the future seems to have thought a good thing). One of them has had to study al-Qaida Terrorism for GCSE History (she says because the boys preferred it to Martin Luther King). This is history? Another’s second-year A Level History is called Interpretation and Investigation, where he has to assess the views of four historians related to a set question, and write a formulaic essay. The presumably excellent example essay is unreadable, and therefore unmarkable. His uncle declared it could only put his own very academic daughter off doing A Level History, her favourite subject. She has just emerged from being told by her school that for GCSE History you can’t use knowledge from your own wider reading. So much for the future.

My recollection of Sammy Middlebrookis that he wrote notes on the blackboard and you took them down, and if you had any sense, learned them. It was unfortunate for the American History A Level paper, however, that his tutoring of an older pupil for university entrance meant we had to use those lessons to study for ourselves. The result was that one boy in the exam room (the gym) asked the invigilator: “Is this the right paper, Sir?” and walked out of the exam.

I have a copy of Sammy’s Newcastle upon Tyne: It’s Growth and Achievement (1950), with its beautifully balanced sentences, signed in his graceful, even, rolling hand. Referring to it just now I discovered two Newcastle Corporation Transport tickets, one for 3d, advertising on the back Cowies For Motor Cycles, and one for 1 1/2d, advertising Mackay Bros & Co Overseas Removals –with the injunction: ‘Save this ticket’. Which, evidently, I did.

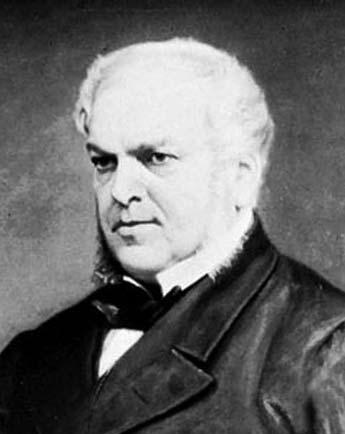

Next to Sammy’s book in the shelf is The Story of The Royal Grammar School Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The forewords, 1924 and 1936, are by that earlier Headmaster ER Thomas (22-48) (still a disciplinary figure in 1944). Appendix I is ‘University Scholarships won by boys of the school between 1874 and 1936.’ Cambridge and Oxford preponderate with 96 scholarships, followed by Newcastle institutions with 17 –Medical College, the College of Physical Science, and Armstrong College. Others are Durham, London, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Manchester universities, South Kensington, Toynbee Hall, Royal School of Mines London, and State Scholarships.

Does this pass the future’s test when quantifying a school’s academic reputation? Or will “young readers”, in Alister Cox’s words, still “be less amused than appalled by this glimpse of the past” too? And which future?

J Harvey Smith (44-52)