6 minute read

The Cost of Education

from ONA 93

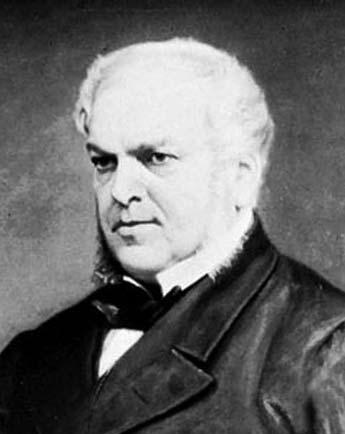

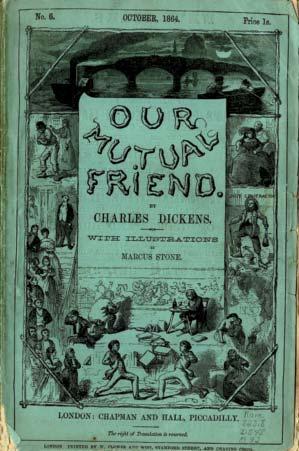

Dicken’s Our Mutual Friend, October 1864. Character, Mr John Podsnap portrays certain striking characteristics of Forster.

Advertisement

In Podsnap’s society he alluded to Forster’s circle of older companions in the phrase, ‘…there was no youth (the young person always excepted) in the articles of Podsnappery’. To Podsnap there was no Europe beyond England, and so with Forster; England was Europe. Podsnap’s rigorously ordered daily schedule, from arising in the morning to retiring at night, and his disapproving view of anything in speech or literature which ‘…would bring a blush into the cheek of a young person…’ were clear references to Forster.

It was not all fair comment; Podsnap could not see his own faults, whereas Forster would indulge in selfmockery, regularly relating the tale of a cab driver calling him “a harbitrary cove”, a description which his friends acknowledged as a good description of him. Thomas Carlyle, who liked him very much and was later one of the executors of his estate, considered Forster to be the “ultimate in harbitrary coves”.

The critic Edmund Wilson saw in Podsnap Dickens’ fear of the character and what he represented; Podsnap does not reflect Forster’s decisiveness and his unfailing support for others, whatever their station in life. The supercilious in the world of the arts referred to him as “the butcher’s boy”, but venom among academics is a constant and although this may have hurt him it did not affect his dedication to his work and his goals.

What Forster’s critics could not deny was that he was a very sincere man and had the brain of a shrewd lawyer; in a drawing by Clarkson Frederick Stanfield of Dickens and friends on a tour of Cornwall, entitled The Logan Rock it is Forster who is atop of the rock, waving to the others below; quite a “jolly cove”, in fact.

His distinction as a classical scholar at RGS was evident in a series of essays on ancient philosophy, which he published in the learned and influential Foreign Quarterly Review, receiving commendation for their perspicacity. His greatest literary impact was in his biography of Dickens, soon after the writer’s death. The three volumes were sensational at the time in revealing so much of Dickens’ harrowing childhood, to which Dickens had only alluded to in David Copperfield, without acknowledging his misery as a boy. The public were fascinated and amazed. Reviews were not all complimentary: Trollope, a mocker of Forster’s background, wrote to George Eliot that Forster was ‘too coarse grained’ to be a reliable commentator.

There was a significant omission in the life; Forster did not mention the relationship of Dickens with the young Ellen Ternan (having now gained notoriety in the film, The Invisible Woman). It was for later writers to reveal more of this affair, still a hot topic today. Forster would have been very much aware of the affair but he was disinclined to cause upset to the memory of his friend or to Dickens’ estranged wife, Catherine, and his large family.

Forster suffered long bouts of poor health, which no doubt contributed to some noted irascibility. He endured long periods of bronchitis and rheumatism and from 1871 onwards these debilities kept him housebound. The ailments also interfered with his role as member and ultimately secretary of the government’s Lunacy Commission, which played a vital role in the nineteenth century and for which he travelled far and wide. This appointment shows the high regard in which he was held by the government for his legal ability and probity.

It is sad that the memory of him and his legacy are not greater. Obituaries were brief in the national press but the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle (5.2.1876) described a man of the north who had ‘…a kind of talent which only just fell short of genius’. W Lockey Harle, one time Sheriff of Newcastle, wrote glowingly in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle of Forster’s youth and upbringing in the North East and was later to write in the Monthly Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend (1888) that Forster owed everything as regards formation of his character to the town of Newcastle.

Many of his personal papers were lost as one of his executors, the Reverend Whitwell Elwin, chose not to rise to the challenge and allowed much to be destroyed. This has presented a problem to biographers and Thomas Carlyle would have dearly liked to have composed a fitting tribute to his friend.

There was thus an obscure ending to the inestimably valuable literary life of this Northumbrian who did so much to establish and perpetuate the life and works of Dickens. He deserves to be better remembered, if only as the butcher’s son from Newcastle who established himself at the heart of the rapidly growing London literary world, displaying prodigious talent and earning the love and respect of so many around him in that exclusive milieu.

By Mark Bowling (83-90)

In 1982 my mother was faced with a daunting issue on behalf of her son –accept the offer of a full scholarship for seven years to the King’s School Tynemouth, or accept a (paid) place at the prestigious Royal Grammar School in Newcastle upon Tyne.

Times were tough –my parents had recently separated and money was a bane of (court) contention. But fortunately I have a mother who believes in what is right, and sees the bigger picture regardless of how tempting the daily snapshot may be.

And so, knowing she had a son who (clearly!) had his wits about him, she left the decision to me. I chose the RGS. I knew it was the ‘better school’, not because of its standing in the top independent schools list, but because it would expose me to a life that I had not yet experienced. A part of me knew that I would have my eyes widened and my brain challenged, although at the time I had not imagined a life different to the one I had. I also did not think of the cost my education would bear.

My father did not support my decision, sadly, nor did he contribute to my education from thereon in. But with support from the courts, and a new central government Assisted Places scheme, I was able to enjoy an education as good as anyone could get in the UK. I know my mother fought tooth and nail to keep me at the RGS. And the RGS supported me all the way through, providing support above and beyond what would be expected of any school, unbeknownst to my fellow pupils at the time.

And 30 years since that pivotal decision, I find myself in Singapore, where I first moved to in 2004, very happily married to my husband of seven years, having enjoyed a long career in ad agencies as a global strategist for the likes of Samsung and Unilever, and now with my own global marketing consultancy, Remarkability. I have circled the globe 100 times over, and had “ A part of me knew that I would have my eyes widened and my brain challenged, although at the time I had not imagined a life different to the one I had. ” my eyes widened much further than they were ever intended, I’m sure! Life has been extraordinary and never dull.

So please believe me when I say my life would not have been the same without financial assistance to take my place at the RGS. Programmes like the RGS Bursaries Campaign change lives. And attending the RGS changed mine.