D-DAY by Jack Edward Frederick Lauder

(writtenin1945andreferencedinD-Day Spearhead Brigade by Christopher Jary)

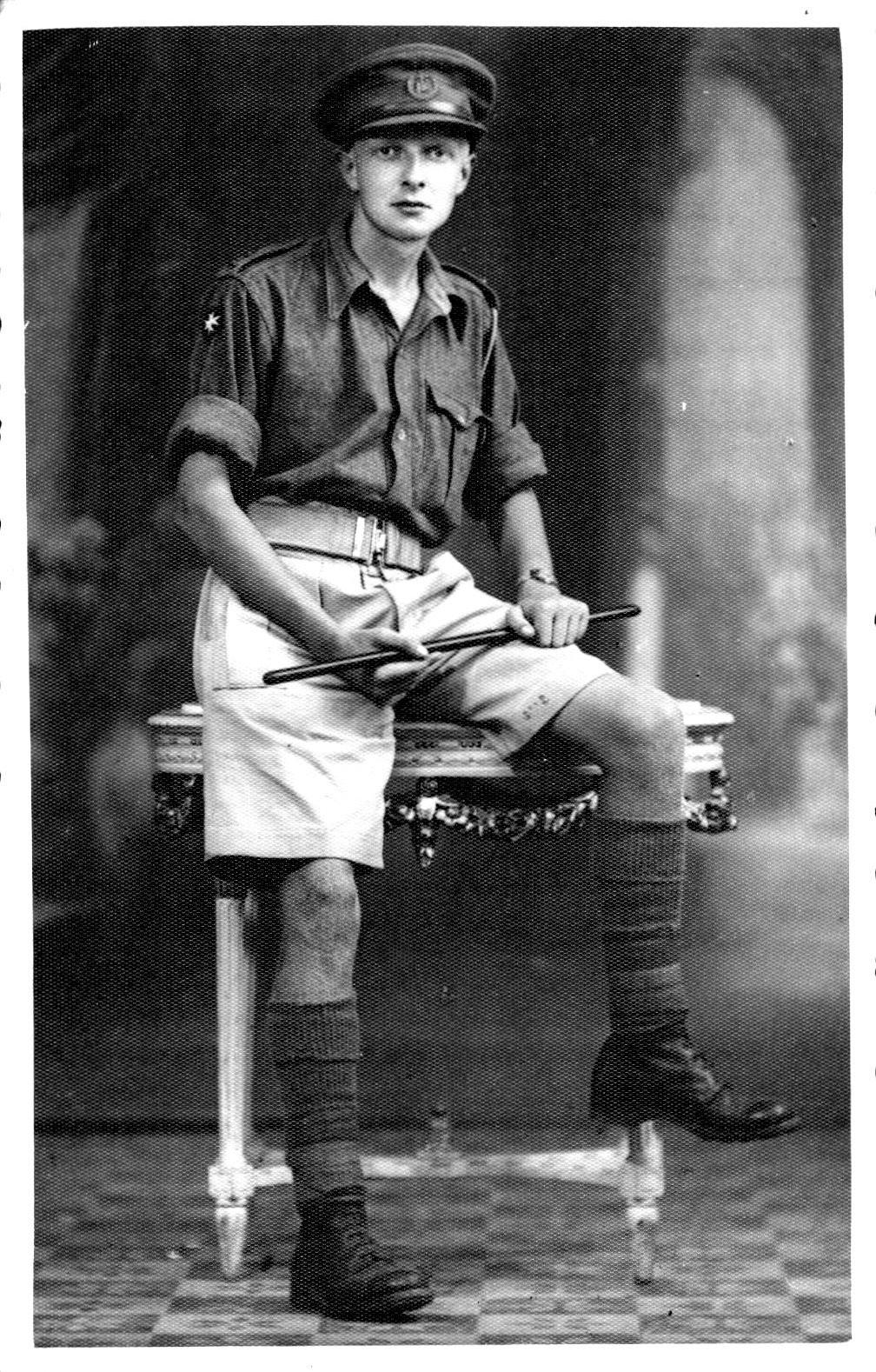

Jack, October 1943, Sicily

It was with a feeling of considerable relief that we finally embussed and moved slowly in a long sinuous convoy from the heavily guarded concentration areas down to Southampton docks. For three months we had been cooped up in various transit camps, which had gradually become more like concentration camps, as the day for the invasion of Europe approached. We had been surrounded with barbed wire, armed guards had patrolled the perimeter of the camps, scores of military and Field Security Police had checked and rechecked our passes each time we moved from one part of the camp to another: in fact, the whole atmosphere was one of the utmost secrecy and security. Moreover, our morale was not heightened by the fact that many of the camps were pitched right in the forests, which were admittedly excellent for camouflage, but were very dark, gloomy and foreboding; however hot the sun, it often did not penetrate through the trees to the tents. In many ways it was a depressing time, and we were all thankful that at last the period of waiting was over.

“ they sensed that this was “it”, that at last the great day, for which Europe had waited so long, had come.

We had not been told that this time we were actually embarking for the invasion, but we knew; our kit had again been checked, deficiencies made up, briefing completed down to the last detail, French currency issued and security measures redoubled. The people of Southampton knew too: they had often seen us on invasion exercises winding in a long, oddly assorted trail from the parks in the city, where we debussed, to the docks; but somehow this time they sensed that this was “it”, that at last the great day, for which Europe had waited so long, had come. There was no great excitement, no cheering; people stood about in small knots, staring curiously; occasionally someone would call out “Good luck lads” or “Give ‘em one for me”; at one point an old lady stepped forward and said “Bless you lad; here, take this”, and thrust a bottle of beer into a man’s hand. And so we slowly made our way to the docks and up the gangplank onto the ship that was to take us to France.

We had been on these boats before, so it did not take too long to settle down and find our way about. Though we did not know it at the time, this was to be our home for the next five days, while we waited for the huge convoys to be marshalled and for the High Command to decide exactly on which day the landing should take place. Privately we all felt varying degrees of trepidation about the coming operation, but outwardly we showed little, said little, and occupied our time as best we could - making final checks of equipment, doing lastminute briefings, and getting in as much rest as possible.

“ As it grew light, we could see more and more ships, hundreds of them, as far as the eye could see ... it was a sight that had to be seen to be believed, and one we shall never forget.

At last the moment came one evening, when the great convoys slid quietly out of Southampton Water and headed across the channel. We tried to sleep that night, but I doubt if many of us succeeded; all our thoughts were centred on the morrow, “Would our plans be successful? Were the intelligence reports really as accurate as was claimed? Suppose the opposition were heavier than estimated? Where should we be this time tomorrow?” Then our thoughts became more personal; we imagined those at home listening to the announcement of the invasion on the morning news and pictured their anxiety over us, until we could get the first letters home to them. Some too, had a deep feeling within them that this was to be their last trip, others somehow felt sure they would come through unscathed, yet others that they would escape with wounds. So we passed an uncomfortable night tossing and turning in the hot bowels of the ship.

In the early hours of the morning, while it was still dark, we got up, fed, and climbed into our equipment: then in an orderly manner we were quietly called forward to our allotted landing craft, into which we filed. Each man had his appointed place, to which he went instinctively. There we crouched in the dark, waiting for the boats to be lowered and the long trip to the coast to begin.

It was not a good morning for the operation: the sky was overcast and as soon as the flatbottomed craft touched the water, they began to toss about like corks on the choppy sea. The landing craft sorted themselves out into their own little formations and headed away from the parent ship. As it grew light, we could see more and more ships, hundreds of them, as far as the eye could see, to right and left - assault landing craft, landing craft bearing tanks, others artillery, uncouth monsters with equipment to fire a thousand rockets, close support craft, hedgerows (?) for blowing gaps in wire, command ships, destroyers, and way back behind us the bigger ships of the navy, the parent ships from which we had come and beyond the ships bearing the succeeding waves of troops. It was a sight that had to be seen to be believed, and one we shall never forget. Above us all the time was a constant “umbrella” of aircraft, protecting us; “umbrella” was the right word, for there was never a moment when there was not a plane in sight. So thorough had been the contribution of the Air Force to D-Day that we never saw a German plane.

The impressiveness of the sight tended to take our attention away from ourselves, our discomfort, inner feelings, and thoughts. In spite, however, of being dosed with pills against seasickness, some of us began to feel the need to use the ‘vomit bags’ with which we had been issued. They were excellent bags, made of first-class greaseproof paper: somebody remarked that they would be excellent for fish and chips.

As the blur on the horizon, which was the coast of France, began to crystallise into definite features, most of us, if honest, would have admitted that we were a bit afraid, but we said nothing. Instead, we began to strain our eyes to pick out the landmarks we expected to see by the beach, where we were scheduled to land. “Look, there’s the tower on the hospital” someone remarked, pointing slightly to our right.

“That must be the breakwater with the big pillbox on it,” said somebody else, indicating a spot to the left of the hospital.

And there, a little further left again, was the long stretch of open beach where we were to land, dotted with vicious looking obstacles, which would be covered by the sea when the tide came in. Each house, building, pillbox and obstacle, which had become so familiar in the photographs, began to stand out in detail as we approached. The tension in the boat increased.

Something seemed to have gone wrong. Where were all the bombs and shells, which were supposed to land on our objective before we reached the shore? Not a bomb or shell burst had we seen so far in our area. Suddenly, whoosh! - the rocket craft to our right had fired its projectiles: at least they should do some damage: but no, they’d miscalculated… the rockets landed in the sea. We were now close inshore.

The moment had come. The ramp was dropped and out went the leading section in water up to their waists. Rat-tat-a-tat, the enemy opened up. The leading Section Commander fell with a bullet in his head; we dragged him from the water but could not stop to do more. We pressed on as fast as we could with our heavy equipment. There were 300 yards of open beach, before the sand dunes afforded us any cover. Our senses were numbed. Our every action was instinctive. Two more men fell wounded. God, our equipment was heavy! A Bangalore torpedo was dropped and lay forgotten.

One platoon was lost. The Company Commander hurried over to order us to take over that platoon’s task. We altered our direction and pressed on. Bullets were now beginning to spatter the sand like raindrops. Two more men fell. We must go on – can’t stop to help the poor devils. This was more than we’d bargained for! Ten more yards to the sand dunes.

I felt a sudden, hot, sharp pain in my leg: I stumbled and fell; my leg felt damp and ached with dull pain. Blast! Some bastard has hit me! I tried to rise but my leg gave way. Somebody stopped to help me, but I waved him on. I crawled blindly forward. After what seemed an age, I sank down behind a sand dune. My runner suddenly dropped like a stone a yard from me. The firing grew heavier: the rest of the platoon hurried on. “Christ, they’re in for a hot spot” I thought. Then everything faded out. I was unconscious. My D-Day was finished.

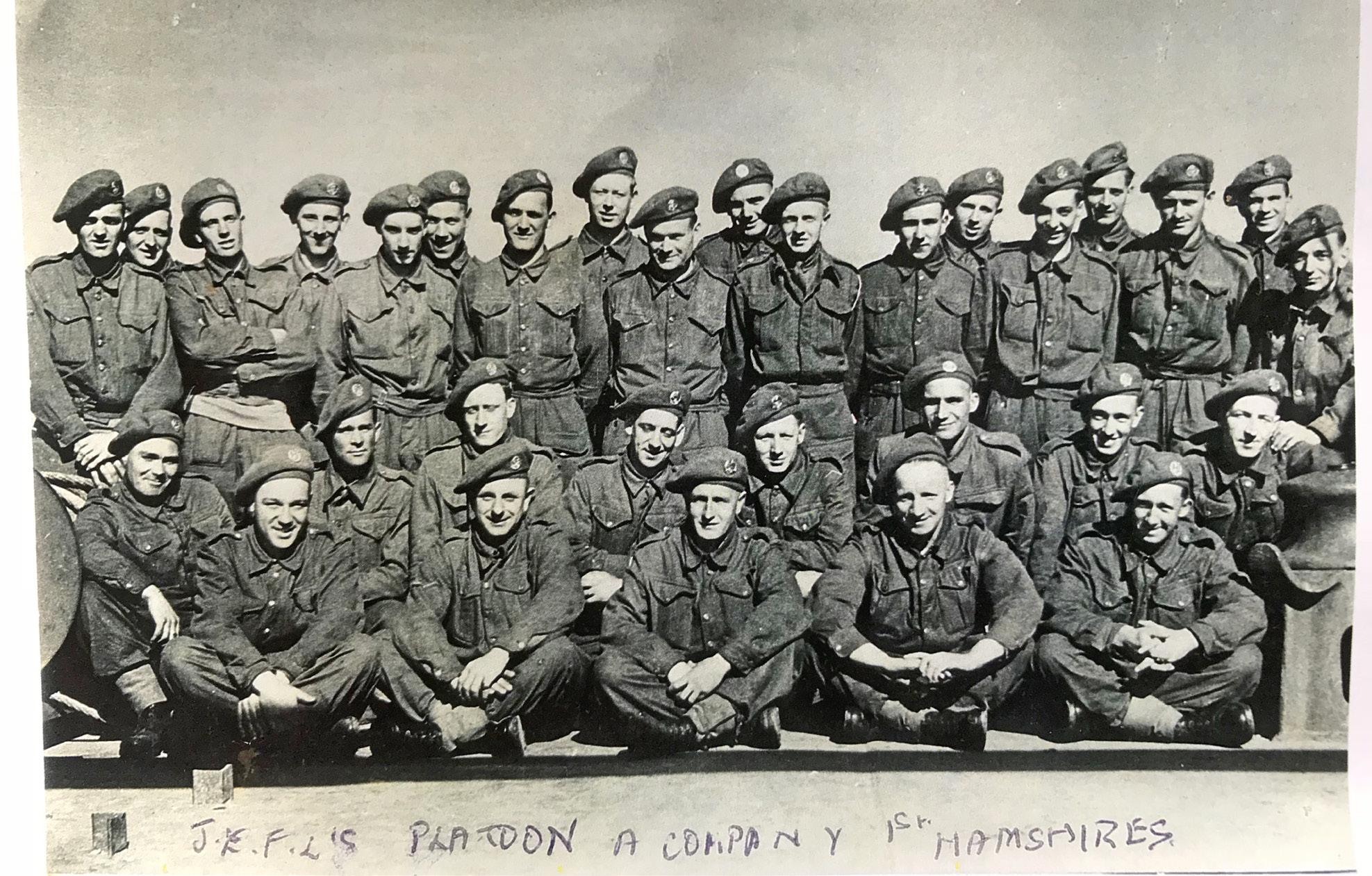

Platoon A Company 1st Hampshires, D Day training spring 1944, Southampton Jack, aged 21, is on the back row 8th from right. He was known as ‘Nipper’ because of his young age. One third of these boys never made it home.