DECOLONIAL DAMES OF AMERICA

Morgan Curtis

IIn the place that has always been known as Copiague, on the long island still known to its people as Paumanok, next to an automobile repair shop, is a small patch of grass with scattered headstones. Three are of human form, earthen effigies, brown skin, with black braids. It was these I found myself carefully cleaning one morning in November 2021. An elderly woman hummed her approval, happy her ancestors were being tended. Other tribal members gathered round, snacking, chatting and raking leaves, happily catching up after months of pandemic isolation. I imagined I looked quite out of place, a young, white woman no one had seen before, at this family reunion in a Montaukett graveyard. Quite a few people asked me how I came to be there.

My story begins in the Victorian town house where I was raised. I grew up surrounded by portraits of my American forefathers, their biographies on the coffee table, their silver in the safe under the stairs. I had what my parents called an “upper-middle-class” upbringing. They instilled gratitude for its privileges, but questions of their provenance were absent. As a child, I was fascinated by a framed, hand-inked family tree, commissioned by my great-grandmother Isobel Ramsay Buckley. I remember noticing the blue squiggly lines beneath certain names. The legend indicated they were each a “Founder of Family in America.” No ancestors preceded those names. According to this tree, between 1620 and 1673 our family spontaneously appeared across so-called New England. An apparent immaculate conception.

I carried this myth with me when I went to college. I remember meeting a Cherokee student, and thinking, perhaps even saying out loud, “Wow, I didn’t know your people were still here.” Not long after, I sat in a dark, underground venue, listening to a Lakota classmate’s

poetry. I felt her gaze directly on me as she powerfully named the pain of Urban Outfitters stealing from her people, appropriating Indigenous culture for fast fashion. I was wearing a t-shirt with the wings of an eagle atop a totem pole. Hot shame flooded me as I covered myself with a cardigan. For the first time in my life, I had a sense that colonization was not just a historical event, but is ongoing.

In the years following, I followed a childhood love for the earth into a fossil fuel divestment campaign, making a moral and financial case for my college to leave behind this death-dealing industry. Soon after, I learned my own family was invested in the same corporations we were campaigning against. I felt I had both blood and oil on my hands. I drifted from my environmental engineering major, opening myself to the political, cultural, even spiritual crisis beneath our fossil-fuel-powered economy. As the depth of my complicity sunk in, I was tempted to once again cover myself up, to try and turn away. The trajectory of my elite education offered the

possibility of refuge and denial. But there was no unseeing what I had seen.

As I got more deeply involved with the climate movement, I found myself in Indigenous-led spaces where I was asked, for the first time in my life: who are your people? I began to understand myself as white, after a childhood in which race had never been mentioned. I remembered that family tree, and it became clear to me that my family’s “early arrival” in North America was a story of immense violence against the land and its original peoples. We saw both as expendable subhuman resources for our own “progress.” Meanwhile, we sacrificed our connection to our own homelands, and the cultural and ecological practices that had sustained us. These are the deeper causal roots of the climate crisis.

This was a history I had never been taught. I was furious, and directed that anger at the living face of this lineage: my father. He seethed in response – “How dare you say that about my ancestors!” – attempting to wrest them back from my rewriting of their story. I would shake with indignation and argue right back. I saw him,

and myself, as bad, wrong, even evil. Perhaps if I was only more forceful, more righteous, more persuasive, he would change, I would change, everything would change. But it didn’t.

IIGo do the work with your own people. This was the mandate I kept hearing from social movements. But I’d managed to put such a distance between myself and the white, wealthy world I came from. I didn’t want to go back. It took time for me to learn that as long as the intergenerational trauma of colonization and enslavement is still carried by Black and Native people, the descendants of the perpetrators must come together to take intergenerational responsibility. This rebalancing of relationships between the land and all of its peoples is necessary for all our survival. It would require learning how to love those parts of myself enough to turn back towards my family, my people, and our history.

So one evening in late 2019, when visiting Granny, my father’s mother, in Connecticut, I went to the attic to see what family records had survived her hasty, grief-stricken move after my grandfather’s passing. I was on my hands and knees when I found a handmade book, cracking at the spine, spilling pages and photographs. It was titled A Gay Nineties Childhood – gay, meaning jolly; nineties, meaning the 1890s – and it kept me up most of the night. It was written by Marian, my great-grandmother’s first cousin. They were raised as sisters in a brownstone in Brooklyn.

Marian’s writing carried me from our time into theirs. Her lilting prose describes the family’s “devotion to that particular part of the earth” on the Hudson in upstate New York where they spent their summers on a country estate. She remarks how “green the grass, how fragrant the air and what a beautiful stillness broken only by the birds singing their late June afternoon lovesongs.” We share a love of horses: “a horse’s lips are one of the loveliest things on earth”; and of the unseen world: “under the harvest moon,

the cornfields were mysterious… I knew there were fairies lurking among the cornstalk ladies.”

Both Marian and Isobel were proud members of the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America. The Dames still exist today, an invitation-only membership organization that considers themselves “entrusted with history’s future.” Marian was one of many members who wrote memoirs in response to the duty of a Dame to “impress upon the young the sacred obligation of honoring the memory of those heroic ancestors whose ability, valor, sufferings, and achievements are beyond all praise.” The organization was founded in 1891, when those of colonial descent wanted a story that could set them apart from more recent arrivals from Ireland, Italy, and Germany. My stomach turned with the twisted irony of being anti-immigrant as settlers – asserting our superiority through seniority on stolen land.

As I continued reading Marian’s neatly typewritten words, I saw how often another truth is hidden in plain sight, for those who are willing to see it. I read Marian’s “favorite story” of her

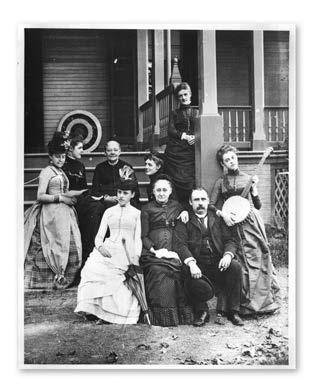

grandfather’s: robbing graves at a nearby “Indian burial ground” as a boy in Geneva, New York. I read of the family’s “hero son” Alexander Ramsay Thompson, who had died “fighting the Seminole Indians.” I saw a young Black boy named Hiram standing stiffly in the back row of a family portrait.

I connected the dots between the time period and geography, the country estates, oil paintings, and numerous servants, seeing a family living luxuriously during the time of remarkable inequality known as the Gilded Age. Searching online, I found a series of obituaries that revealed the source of our family’s wealth: a cotton and wool mill, dry goods, railroads, gas, insurance, mining, and ports, including contracts with the Committee on Indian Affairs. All industries intricately bound up in enslavement and genocidal westward expansion. My great-great-great-grandfather Thomas Townsend Buckley did so “well” that his sons never had to work.

I shook my head with grief and rage, grimly receiving another layer of what it is I’m respon-

sible to remedy in this lifetime. For I’ve found many such stories in my journeys around the cupboards, file folders, and bookshelves of my extended family in so-called New England. Turns out, the papers that are proudly stored away by generations previous, kept for posterity, are so often a perfect record of our participation in the theft of land and labor. Sometimes it feels like they’ve been waiting for me, ready to be repurposed for my generation’s reckoning with our family’s past.

IIII use my ancestral stories as a map, from the past and into the future. I am guided to the places where memories may linger upon the land: historic houses, graveyards, massacre sites. One time, I took my parents with me. We went to Riverview, the estate on the Hudson in Marlboro, NY, that was in our family until 1918. On arriving, my father commented on how the

landscape had been ruined by the “down-market” housing on subdivided lots. I thought to myself that it had been ruined long before that, as Munsee Lenape territory was manipulated to resemble English manor gardens. We could see the house was uninhabited; the garden wild, the paint peeling. A plaque from the National Register of Historic Places hung beside a permit notice warning of upcoming construction. We walked around the house, past the empty swimming pool, past the verandah where a photograph of Marian in her girlhood finest was taken. The basement level of the house was open to the air on one side, and we stepped inside the cool brick structure. Before I knew it, my father had pulled himself up through the floor joists, opened the basement door from the inside, and beckoned me up the stairs. He shushed my remark about the white privilege that let us brazenly enter.

Together, we walked the halls of our ancestors. My father spoke his imagination out loud: of them receiving guests in the front room, eating at a long table in the dining room, sitting for

cocktails in the living room and tinkling on a grand piano. All I could see was how that world was gone, unraveled, decayed, remaining furniture dusty and broken, wallpaper faded and falling. I traced my fingers across the serving counter between the kitchen and the dining room, and found myself walking up the backstairs, to a small room with low ceilings. The steepness of the stairs reminded me: this house was also a place of work. Perhaps some of those who served my family – as butlers, footmen, cooks, maids, governesses and groundskeepers – slept in this very room. This was their home too, however uneasily. It was only in 1827 that slavery had finally become unlawful in New York State. I cannot know the texture of these relationships, but the inequity feels clear. These people gave immense amounts of labor to my family, while all of the family’s ill-gotten wealth went to their descendants, including my great-grandmother, who never had to work, in the household or beyond. I believe I am the first generation of my father’s family in North America to not experience being

served by Black people in the home. And my great-grandmother’s trust fund is still generating wealth today.

I said a quiet prayer, of gratitude and apology. Back outside, I gathered a bunch of mugwort, that protective herb native and sacred in both Europe and North America. “You, witch, you,” my father said, with a half-smile, as I whispered my goodbyes.

When I got home, I re-opened A Gay Nineties Childhood, searching for a story I remembered about one of the people who lived and worked in my ancestors’ homes. His name was Charles Squires. In Marian’s words: “Charles had come to Montague Street when he was seventeen and had been Grandfather’s valet. After Grandfather’s death he succeeded the coachman in the country and was houseman in town… Charles always walked behind me. This bothered me for I should have preferred to skip beside him, holding his brown hand but he would force me, as it were, to stay in my place. He was half Negro and half Montauk Indian. His Mother was the last pure-blooded Indian of that tribe. The tribe

owned a vast acreage on Long Island and, as the Montauks died, they left their lands within the tribe. Consequently, Charles was actually a rich man but so faithful to us that he remained with us over fifty years, dying at last because of his sorrow when my father died. They were the same age, one day apart.”

With a lump in my throat, I began to research, yearning to see beyond the white gaze of Marian’s storytelling. According to the 1850 Federal Census, Charles Squires was born in 1848, to Daniel, enumerated as Black, and Charlotte, deemed by the census taker as Mulatto. I found him again in 1860, a young boy, Mulatto, birthplace unknown, he and his family living in Huntington, NY, not far from their ancestral homelands in the far reaches of what we now call Long Island. By 1880, he was an unwed coachman at Montague Street in Brooklyn, his name in cursive next to those of my ancestors. By 1900 he was married to Martha Fowler, with a six-year-old son, Arthur, at home. Charles’ mother lived to ninety-nine, passing in February 1916. Just six months later, Charles

himself was with the ancestors. I imagine that if he died of sorrow, it was for the loss of his mother, not his master.

Next, I turned my attention toward researching his people. Squires, it turns out, is a common Montaukett name, and Martha’s family name Fowler is too. In 1906, the Montaukett people received a devastating blow at the hands of New York State Judge Abel Blackmar when he declared to the over 200 Montauketts sitting in his courtroom that their tribe no longer existed, and they had therefore lost their claim to any remaining tribal lands. Marian’s idea of Charles’ loyalty to our family despite his wealth in vast acreage dissolved. I could now see: almost none of her story about Charles held true.

IVOne mention of Charles and his elderly mother was in a 2015 article written by Sandi Brewster-walker. Looking Sandi up, I learned

she is a historian, genealogist, freelance journalist, and executive director & government affairs officer for the Montaukett Indian Nation. She works closely with present-day Montaukett Chief Robert Pharoah on the effort to restore the tribe’s state recognition. Eventually I found the courage to hit send on an email, introducing myself and describing the book, in case any of Charles’ descendants might wish to read the part of his story preserved in my grandmother’s attic. Sandi responded right away: “Call me,” with her number. My hand shaking, I typed it into my phone, and an hour or so after beginning my research, I was speaking with Charles’ living relative.

Sandi’s family intermarried with the Squires family many times, Charles is a cousin of hers in multiple ways, and she was very excited to read the book. We dove into stories: of her Montaukett family, and my white, wealthy family, just forty miles or so apart. Sandi’s grandfather Job was a prize-winning gardener, growing acres of dahlias. At the same time another great-greatgrandmother of mine was a decorated member

of the Garden Club of America on Long Island. We marveled at how close and far our stories come.

Sandi told me about how the tribe’s loss of recognition was often accompanied by news coverage of the supposed “Last Montauk Indian,” just as Marian had described Charles’ mother. For centuries, she shared, the two families who have led the Montaukett Indian Nation are the Pharaohs and the Fowlers. Charles’ mother was a Pharaoh, she told me. I found words to make clear that I don’t consider Charles’ serving my family to have been a just arrangement, especially as a Black man, a Native man, serving a white family, within living memory of slavery. I shared that my ancestors had enslaved many people, of both African and Native descent, over two hundred years in so-called New England, and Charles’ story shows me how the peculiar institution morphed only slightly through the nineteenth century.

“Don’t go feeling guilty,” Sandi reminded me, before we closed the conversation. I shared about the work I now do organizing white

people for reparative redistribution of wealth, and offered that fundraising is something I can do, if needed. She found my website and called me back: “You’re serious aren’t you?” A flurry of emails followed: history books and articles for me to read, book clubs to be part of, photographs of her own beloved ancestors. Some months later came an invitation down to Long Island, to that day of gravesite restoration. I was invited to arrive early, to help ready the burial grounds for a Native American Heritage Month event. I was up late the night before, deep in my family tree, learning of another branch of my family who were early colonial settlers on Long Island. I arrived with some trepidation, perhaps reverberating with ancestral memory, a projected fear my settler ancestors had of the people of this place. Despite my shyness, I was met with an abundance of warmth from everyone Sandi introduced me to. I was honored to meet another family member of Charles: Myra Squires. She knew about Arthur, Charles’ son, after whom a local American Legion Post was named. She also recalled

that a number of tribal members had worked for wealthy families at that time, including as respected coachmen. We hugged, took pictures for her to show her family, and wondered what our ancestors were making of our reunion.

Sandi had invited me to contribute financially, and we got to sit together on one of the two stone benches she had bought with those funds for the burial ground – for visitors to sit, meditate, and acknowledge the homelands of the Montaukett Indian Nation. I’m excited to keep supporting her efforts, in particular her vision to build a museum for the Montaukett to tell their own story, a form of “historic preservation” so sorely needed. I pray (and write letters to the Governor) that their nationhood will soon be re-recognized by the state of New York, as a step toward one day having sovereignty over their ancestral homelands once again. I’m learning that Native peoples dream of futures we all need. We are a dozen generations into colonization of these lands. May it not take as long for those dreams to come true.

I dedicate these pages to the memory of my great-grandmother, Isobel. Perhaps it would be easier to leave her behind, to cast her off as a relic of another time, to distance myself from any notion of being a Colonial Dame. That’s always there, the choice to vanish into whiteness, to pretend these are not my stories, not America’s stories. But if we do not claim these narratives they will just be continued by others in much the same way as they have for generations: in the memoirs, statues, textbooks, house museums, and archives of the Colonial Dames and their like. Only when we, the white descendants of the perpetrators, claim these ancestors as our own can we take responsibility for what was done in our names, and see what we still do in their image. Our history requires of us a profound reckoning, the willingness to make different choices than our ancestors did before us. For injustice haunts us until it is put right, even over generations. It is through this work of repair we

V

will find our way back to our own humanity. This is both material and spiritual work.

I imagine one day I too will be an old white lady of colonial descent. I hope that, by then, we stand for something different than we do now. Perhaps a Decolonial Dames of America, with a reimagined “sacred obligation” to act swiftly and with courage to stand with Black and Native communities in their efforts to bring about long-overdue reparations and land return. Through this we too can keep the memory of our ancestors close; by telling the truth of their times, committing to transmute the trauma they caused, and not letting wealth inequality, racial violence, or climate chaos be the final chapter of their legacy. If white supremacy is to end in this country, its own children must turn around and face its history, saying: Yes, those are our people. We are them and they are us. We did this. And now we will work to undo it.