14 minute read

Feature

from June 25, 2015

Edward Abbey was the original environmental monkey-wrencher. His popularity is resurgent— maybe just in time.

Although it’s been nearly three decades since Edward Abbey drained his last can of beer and flung it onto a Forest Service byway, the author’s suasive prose and thorny legacy still thrive within certain enclaves, including those of the disaffected youth, thank goodness, who seem to arrive with each generation like the hardy grasses that poke through buckled concrete. By the time they find Abbey, they’ve dispatched their Thoreau and von Mises, and they’re thirsty for stouter brew. (We’ll forgive them their late-model SUVs and Sprinter vans.) To them, Desert Solitaire and The Monkey Wrench Gang are as necessary worldview additives as Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, and some, charmed by Abbey’s not-so-subtle call to agitate, have Googled up the public domain copy of “Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching,” compiled by “Various Authors,” like “T.O. Hellenbach” (but actually written by Abbey’s bestknown disciple, Dave Foreman, the founder of Earth First!).

Advertisement

Whether these latter-day eco-warriors have employed the necessary hammers, wrenches and granulated sugar to wreak destruction on various species of Caterpillar, they’re not saying. Perhaps more inspired by Bill McKibben’s call for a sensible middle path, they’ve traded hardware for social media and video cameras, which are probably stickier stuff than Karo Syrup five decades removed from the more physical strain of civil disobedience that once swept the country. All the same, you can almost hear Abbey wailing from the depths of his unmarked grave, “What we need here is a little precision earthquake.” Fortunately, many still have their ears to the ground. After 26 years of repose under the hardpan of the Dark Head Wilderness, a temblor of sorts has disinterred Abbey’s spirit, and he’s being feted more this year than any other in recent memory. Apparently, Abbey is needed.

continued on page 14

Photo illustration by Priscilla Garcia

This April, W.W. Norton

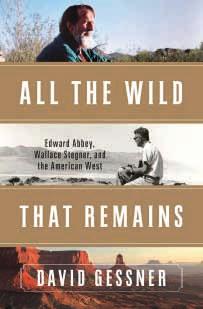

Gessner, Stegner, and Abbey

The writer, professor, and environmental provocateur David Gessner lounges in his writing shack out back of his North Carolina house, a nonsmartphone to his ear, a Ranger pale ale in his belly, and another in his hand.

We’re chatting about his latest book, All The Wild That Remains, his encomium to two giants of American literature, Ed Abbey and Wallace Stegner. The shack’s windows face an expansive marshland cut by the turbid waters of Hewletts Creek, a slow-moving meander that flows east to the Atlantic by way of the Intercoastal Waterway, through which Gessner occasionally kayaks, or plunges into headfirst. I imagine his flip-flopped feet propped up on his writing desk amidst a scrum of dog-eared books and that morning’s writing as the sun sets behind the ornate cupolas of the University of North Carolina Wilmington 10 or so miles to the west, where he teaches literature and creative writing during the fat part of most days.

When I last saw him in Reno, he had forgotten to pack a belt, so his trousers were secured with a hank of clothesline, Jethro Bodine style, and he read huskily from All The Wild That Remains to a packed lecture hall at the university. He also paid a visit to ecocritic Michael Branch’s seminar in environmental literature and humor, where I was lurking as a student, and he discussed the state of the nature writing art, the new book, and his eight others, including the genre-bending, anti-Thoreauvian Sick of Nature.

With All The Wild That Remains, Gessner has limned a quest for truth, and perhaps a bit of redemption, as he peers through the eyes of wise and voluble elders whose voices live through the printed word. As such, it’s a classically Western construct, and Gessner, no shrinking violet, asks tough questions and doesn’t shy away from delivering the news.

That he would tackle Abbey and Stegner at a time when the West confronts massive drought and the Sierra Nevada snowpack is the leanest in recorded history seems especially propitious, given that both authors propounded on the aridity of the West, and questioned the sustainability of life west of the Hundredth Meridian.

Stegner presaged that the lack of Western water would risk the region’s livability, and worried that one day its thirsty chickens would come home to roost. Abbey shook his head and rolled his eyes as he witnessed road building, dam construction, and nonstop development, and worried, strenuously, that the many mouths and prodigious thirst of an evergrowing citizenry out west would outstrip nature’s supply, and prove the ruination of the landscape he deemed sacred. He decried growth, procreation, and man’s presumed dominion over nature. Both men lived in the West for most of their lives, Stegner in a home in Los Altos Hills near Stanford University, and Abbey variously in New Mexico, Utah and Arizona, which is where he died. Abbey’s voice of perturbation contrasted with Stegner’s quieter and behind-thescenes efforts to reform environmental practices; both made persuasive cases for wild domains as havens of saneness in an ever lunatic world—Abbey, prominently, through his books, like The Monkey Wrench Gang, and Stegner more quietly but no less effectively through his many novels, his famous “Wilderness Letter,” and the assistance he gave to then Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall, in crafting verbiage that would inform the 1964 Wilderness Bill.

The writings of both men changed lives—in Abbey’s case, perhaps, the taking up of arms, and in Stegner’s case, “connecting the dots,” as Gessner puts it, between “land, economy, resources, geographies and cultures,” a mental model taken to heart by at least one of the country’s most influential spokespeople for wilderness, Wendell Berry, whom Gessner visits early on in the story. Berry credits both Abbey and Stegner for “lighting his way” as a writer, but perhaps it was Stegner who influenced him most, because, as Gessner quotes, “Wendell Berry had said he wanted to take Stegner’s ideas and try them out in his own neck of the woods… .”

Fast forward to Gessner’s American West. All the Wild That Remains doesn’t just confront the ravages on the landscape due to climate change. As literary heir to both Thoreau (whom Gessner once described to his daughter as “the man who ruined daddy’s life”) and Michel de Montaigne, Gessner has used his books as a kind of gestalt. He of course owes a literary debt to Stegner and Abbey: Gessner is inspired by Abbey’s inclination to disturb the system and also Stegner’s inclination to work within it. Gessner harks to the voice of a renegade but also to the voice of a buttoned-down professor. EarthFirst! vs. the Sierra Club. Dylan vs. Seeger.

Abbey and Stegner were two of the most resounding of the many voices that have rung through the American West, ultimately conjoined in their philosophies, and it’s this dynamic yin-yang Gessner attempts to reconcile in the book.

At the beginning of his journey west, Gessner received an email from environmental writer Terry Tempest Williams, who offered what Gessner called a koan of sorts. She characterized Stegner as the radical and Abbey as the conservative, a notion inverse to the one most people hold about the two men. Gessner periodically revisits Tempest-Williams’ proposition in the book, and concludes that Stegner’s radicalism stemmed from his rootedness and devotion to home and work and family—steadfast and resolute—rather than restlessly searching for the Big Rock Candy Mountain.

“Wilderness is our first home,” writes Gessner, “the laboratory where human beings were created, where the human genome was hammered out over millennia, and that essence does not suddenly change in a hundred years because someone invented a car or computer. Our needs are still the same.”

Indeed, in All The Wild That Remains, Gessner makes clear, as did both Abbey and Stegner, that a little bit of wild goes a long way. released All The Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West (see side-

—Brad Rassler

For a complete interview regarding All The Wild That Remains, check out http://sustainableplay.com/art-of-the-wild-davidgessner-and-all-the-wild-that-remains. bar), written by the “don’t call me a nature writer,” David Gessner, who interweaves Abbey’s unrepentant wildness and Stegner’s brainy restraint as he follows their separate but ultimately conjoined ideological perambulations through the Western states while reflecting on his own environmental coming of age. Gessner, an irreverent ecocritic himself who not only possesses a— gasp—sense AlltheWildThat Remains channels of humor, but environmentalists who also boldly Edward Abbey and paddles and Wallace Stegner. wades into the raw material he celebrates in his writing, has been blogging about Abbey as of late in anticipation of the book’s release. In a recent piece for Orion, he describes the 130-page file the FBI compiled on Abbey, and ponders how Cactus Ed would have fared in post-9/11 society; he surmises that Abbey could have found himself behind bars. As for Abbey’s relevance and sustained appeal, indeed; Gessner gives a nod to those who still read him and the millions who have been inspired by him, including his own self.

In May, University of New Mexico Press—of Abbey’s alma mater—released Sean Prentiss’ Finding Abbey: The Search for Edward Abbey and His Hidden Desert Grave, a travelogue-cum memoir-cum-biography in which Prentiss describes his quest to, well, find Abbey’s hidden desert grave. Prentiss, a barrel-chested teacher of creative writing and self-propelled sports enthusiast, logged 7,000 miles trailing Abbey’s literary spoor, from his birthplace in Pennsylvania to his current place of repose somewhere in Arizona. He meets up with several of Abbey’s cronies—Jack Loeffler, Dave Petersen and Ken Sleight (a.k.a. Seldom Scene Smith)—and listens as they explain how Abbey’s worldview affected their own. “Just having a wilderness to disappear into, when you’re in outlaw environmentalist mode, is a comforting thought,” Loeffler tells Prentiss. Does Prentiss find Abbey’s grave? You’ll have to read the book to find out, but it would appear that Prentiss found something more about himself as he crisscrossed the dun backroads of the desert Southwest.

Abbey appears on film this year in at least two features and an animated short. First, he makes a cameo in Yvon Chouinard’s new award-winning documentary DamNation, a film that deconstructs the pseudo-science that spurred the construction of 75,000 dams in this country. The film, which for its blending of history and artistry is deserving of the accolades being heaped upon it, should have been dedicated to Abbey, because the movie’s denouement was directly inspired by his writing.

But it’s not until an hour into the film that we catch a glimpse of him, standing atop a parapet downstream of the Glen Canyon Dam, calmly advocating for “sabotage and subversion as a last resort,” in his stiff-jawed baritone. Who knew the guy was so photogenic? Scrap the beard, and he’s a cross between Gary Cooper and Gregory Peck, with a voice like the latter’s. This Abbey-inspired documentary, which is as beautiful as it is educational, is worth seeing for no other reason than to watch the stunning Katie Lee and friends cavorting through “the place no one knew,” the magical stretch of the Colorado so poignantly described by Abbey in Desert Solitaire, now submerged due to the Glen Canyon Dam.

The organizers of this year’s Wild and Scenic Film Festival screened a two-minute short, “A Line in the Sand,” produced by Justin Clifton and Chris Cresci and created by motion graphics and 3-D artists Barry Thompson and Eric

Sean Prentiss recounts a contemplative search for Edward Abbey’s desert grave in FindingAbbey.

Bucy of Half Wild Studios. The film is a graphic meditation on some of Abbey’s more pungent quotes, which are spoken by voice actor John Drew.

Finally, Abbey stars in Wrenched, a 90-minute feature film by director ML Lincoln, which describes the arc of the environmental direct action movement, a.k.a. monkey-wrenching, inspired in large part by the book of the same name. While Wrenched isn’t exactly a biopic, Abbey plays a central role as the one literary agitator to rule them all. Loeffler and Sleight are joined by Dave Foreman, Doug Peacock, Robert Redford, R. Crumb, Terry Tempest-Williams and bookstore owner Ken Sanders, among others, to discuss Abbey’s influence on the movement.

Which brings us right back to Gessner, who claims that those who have walked Abbey’s path, like others inspired by the prose of powerful writers, were perhaps looking for something like a father figure. “A hunger for models. For possibilities. For how to be in the world.” Abbey, for his part, wanted none of it. Sounding a lot like Bob Dylan, Abbey called himself an entertainer. “I have no desire to be a leader of any kind. I dislike being called a guru. I think every man should be his own guru. Every woman their own gurette. We should all be leaders.”

All the same, Abbey’s measured voice sounds fairly guru-like these days in light of the dark news that continues to pour out of science journals like turbid water from a breached dam. The appeal of his good-natured orneriness, and satirical pissed-offness, is a refreshing tonic after too many years of science-speak and hedging and soundbites carefully parsed so as to not startle the electorate. While he was living, Abbey laid it out plainly, calmly, sans bullshit. Overpopulation. Capitalism. Man’s perceived dominion over nature.

“Most humans do not have the self-control to refrain from using that power,” Abbey told his friend Loeffler in a taped interview.

Gessner is a kind of nature writer gone wild, although he’s exquisitely self-aware, brutally honest about his own peccadilloes, and like Abbey, he takes literary risks. While he falls well short of advocating for the destruction of amortizable assets, he’s the guy who dished on Thoreauvian nature writing as an exercise in preaching to the converted. Here he acts as a literary historiographer who stops short of tracking his quarry to his final resting place.

“I knew I would likely be able to find the spot,” writes Gessner of Abbey’s tomb. “I had good contacts, old friends of Ed’s, and thought it wouldn’t be too hard to figure out the location. But when I got to the Abbey library in Tucson, I changed my mind. … I decided, finally, that I would let the poor man rest in peace.”

Rest in peace? Not this year. Ω

Edward Abbey, Environmentalist, author

280945_4.75_x_5.5 4/7/15 11:00 AM Page 1

Wrenched documents Edward Abbey’s role as an eco-activist pioneer.

CALL NOW & SAVE UP TO 84% ON YOUR NEXT PRESCRIPTION

Drug Name Qty (pills) Price* Drug Name Qty (pills) Price*

Viagra 100mg 16 $ 99.99 Viagra 50mg 16 $ 79.99 Cialis 20mg 16 $ 99.99 Cialis 5mg 90 $129.99 Levitra 20mg 30 $109.99 Spiriva 18mcg 90 $169.99 Celebrex 200mg 90 $104.99 Advair 250/50mcg 180 ds $184.99 Zetia 10mg 100 $109.99 Crestor 20mg 100 $154.99 Combivent 18/103mcg 600 ds $119.99 Symbicort 160/4.5ug 360 ds $194.99 Cymbalta 60mg 100 $174.99 Namenda 10mg 84 $ 97.99 Nexium 40mg 90 $109.99 Diovan 160mg 100 $ 72.99 Aggrenox 200/25mg 200 $121.99 Entocort 3mg 100 $109.99 Propecia 1mg 100 $ 69.99 Januvia 100mg 90 $209.99 Quinine 300mg 100 $ 74.99 Ventolin 90mcg 600 ds $ 59.99 Pentasa 500mg 100 $109.99 Avodart 0.5mg 90 $ 99.99 Pradaxa 150mg 180 $459.99 Vagifem 10mcg 24 $ 94.99 Xarelto 20mg 84 $444.99 Asacol 800mg 300 $229.99 Tricor 145mg 90 $119.99 Colchicine 0.6mg 100 $ 89.99 Abilify 5mg 100 $139.99 Singulair 10mg 84 $ 33.99 Plavix 75mg 90 $ 26.99 Premarin 0.625mg 84 $ 75.99 Pristiq 50mg 100 $134.99 Janumet 50/1000mg 84 $184.99 Protonix 40mg 84 $ 29.99 Aciphex 20mg 100 $ 69.99 Evista 60mg 100 $134.99 Flovent 110mcg 360 ds $114.99 Niaspan 500mg 84 $ 84.99 Boniva 150mg 3 $ 49.99 Xifaxan 200mg 100 $139.99 Multaq 400mg 180 $574.99 Flomax 0.4mg 90 $ 49.99 Ranexa ER 1000mg 100 $114.99

All pricing in U.S. dollars and subject to change without notice. *Prices shown are for the equivalent generic drug if available. ✔ Over 1500 Medications Available ✔ Price Match Guarantee ✔ Call for Free Price Quote ✔ Prescriptions Required ✔ CIPA Certified

Toll Free Phone 1-800-267-2688

Toll Free Fax 1-800-563-3822 Shop: www.TotalCareMart.com or Call Now! 1-800-267-2688

iNVite S You to t He

Hosted by Soroptimist International of Yerington Saturday July 11, 2015 | 12:00pm to 5pm Lyon County Fairgrounds | 100 Hwy 95A, Yerington, NV

Home Brew Competition with cash prizes and beer garden with all the beer you can drink responsibly. Sierra Express Band will be playing while you enjoy numerous art and food vendors. AdmiSSioN $35 ANd deSigNAted driVerS $15 Entry includes commemorative glass and as much Beer as you can responsibly drink Hotel packages call (775) 463- 5310 Entry into Home Brew Competition call (775) 720-5686 For more information check out our website: yeringtonbrewfest.org