T

here are a lot of reasons that people go to the desert. To reflect, to hide out, to be tempted for 40 days. My friend Roxanne and I are here to clear our heads. In the last year, we’ve been dealing with all kinds of old neuroses, our newly minted 30s, and something called ERSS—Election Related Stress Syndrome. It’s the thing that happens when you hold your breath from November to mid-January, and your soul goes numb. It’s a debilitating condition that can only be reversed by looking at something big and beautiful. That was the plan, anyway—to get a dose of beauty before inauguration, hitting four earthwork sculptures in five days, including the “Sun Tunnels,” “Spiral Jetty,” “Double Negative” and “Las Vegas Piece.” Right now, we’re lost. My GPS says we are circling 37°N -114°W, but there is no sign of the faint machine scratches that will tell us whether or not we’ve found Walter de Maria’s elusive “Las Vegas Piece.” Just cowtracks and mountains forever. About an hour ago, we lost sight of our truck, and 10 minutes back, we decided that if we have to, we will eat Machete, our schnauzer-Jack Russell terrier companion, to stay alive. “She would want us to live,” Roxanne says. I’m noticing things that delirious people notice. Wavy lines on the horizon. The strange way a branch has twisted into a rabbit face. How much Roxanne looks like an attractive, female version of Russell Brand. We are down to a quarter of a water bottle, and I’m losing brain cells almost as fast as the questions are coming in. How did we get here? Is land art a hoax? What does dog taste like? Will Donald Trump unleash a fiery Armageddon upon the world? Do I smell? Does it matter? Does anything matter? We were in a better place earlier this week.

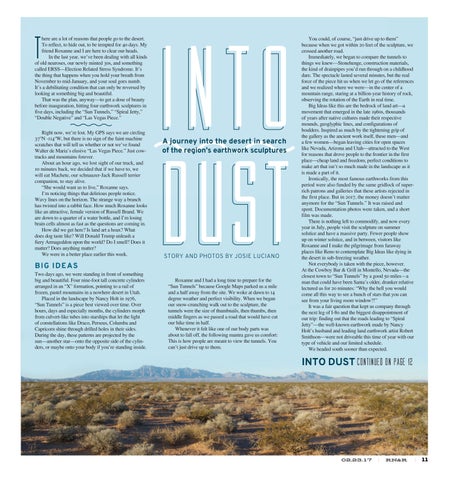

a journey into the desert in search of the region’s earthwork sculptures

STORY AND PHOTOS BY JOSIE LUCIANO

Big ideas Two days ago, we were standing in front of something big and beautiful. Four nine-foot tall concrete cylinders arranged in an “X” formation, pointing to a rail of frozen, pastel mountains in a nowhere desert in Utah. Placed in the landscape by Nancy Holt in 1976, “Sun Tunnels” is a piece best viewed over time. Over hours, days and especially months, the cylinders morph from culvert-like tubes into starships that let the light of constellations like Draco, Perseus, Columba and Capricorn shine through drilled holes in their sides. During the day, these patterns are projected by the sun—another star—onto the opposite side of the cylinders, or maybe onto your body if you’re standing inside.

Roxanne and I had a long time to prepare for the “Sun Tunnels” because Google Maps parked us a mile and a half away from the site. We woke at dawn to 14 degree weather and perfect visibility. When we began our snow-crunching walk out to the sculpture, the tunnels were the size of thumbnails, then thumbs, then middle fingers as we passed a road that would have cut our hike time in half. Whenever it felt like one of our body parts was about to fall off, the following mantra gave us comfort: This is how people are meant to view the tunnels. You can’t just drive up to them.

You could, of course, “just drive up to them” because when we got within 20 feet of the sculpture, we crossed another road. Immediately, we began to compare the tunnels to things we knew—Stonehenge, construction materials, the kind of drainpipes you’d run through on a childhood dare. The spectacle lasted several minutes, but the real force of the piece hit us when we let go of the references and we realized where we were—in the center of a mountain range, staring at a billion-year history of rock, observing the rotation of the Earth in real time. Big Ideas like this are the bedrock of land art—a movement that emerged in the late 1960s, thousands of years after native cultures made their respective mounds, geoglyphic lines, and configurations of boulders. Inspired as much by the tightening grip of the gallery as the ancient work itself, these men—and a few women—began leaving cities for open spaces like Nevada, Arizona and Utah—attracted to the West for reasons that drove people to the frontier in the first place—cheap land and freedom, perfect conditions to make art that isn’t so much made in the landscape as it is made a part of it. Ironically, the most famous earthworks from this period were also funded by the same gridlock of superrich patrons and galleries that these artists rejected in the first place. But in 2017, the money doesn’t matter anymore for the “Sun Tunnels.” It was raised and spent. Documentation photos were taken, and a short film was made. There is nothing left to commodify, and now every year in July, people visit the sculpture on summer solstice and have a massive party. Fewer people show up on winter solstice, and in between, visitors like Roxanne and I make the pilgrimage from faraway places like Reno to contemplate Big Ideas like dying in the desert in sub-freezing weather. Not everybody is taken with the piece, however. At the Cowboy Bar & Grill in Montello, Nevada—the closest town to “Sun Tunnels” by a good 50 miles—a man that could have been Santa’s older, drunker relative lectured us for 20 minutes: “Why the hell you would come all this way to see a bunch of stars that you can see from your living room window?!” It was a fair question that kept us company through the next leg of I-80 and the biggest disappointment of our trip: finding out that the roads leading to “Spiral Jetty”—the well-known earthwork made by Nancy Holt’s husband and leading land earthwork artist Robert Smithson—were not driveable this time of year with our type of vehicle and our limited schedule. We headed south sooner than expected.

iNTO dUsT continued on page 12

02.23.17

|

RN&R

|

11