6 minute read

FETCHING WATER

How to stand still in living water: Plant yourself.

Spread your toes. Press them into the soil or sand Dance your feet into the earth

Advertisement

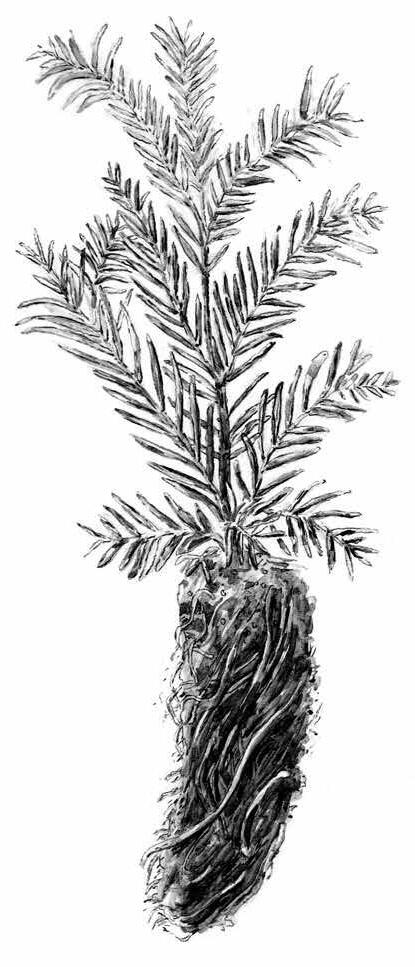

Like the Ede plant, you need to plant yourself in mud, Take root and hold on.

Only when your feet are rooted, can you let go of your body Turn your joints to water, Surrender to the ebb and flow, Remember you are also water.

Then

For as long as I could remember, we awoke before the sun to walk ancient paths around my village. Pathways softened by millennia of rainy seasons and packed down by humans and animals lured by this pied piper of sorts. Fresh water. We would wake and hike down to the valleys to find her awake and winking in the dawn light.

Along the path, a steady stream of human bodies wet from sweat and slosh; clutched and balanced jerrycans, clay pots, and buckets. We met and greeted each other. “Unu awunno!” May you not die. Live! Along the path news was shared. Our social selves, entangled; our memories, woven together.

At the bottom of the valleys were the rivers, life. Everyone entered the water at different points to commune with her in various ways: to bathe, launder, drink, gossip, play, and fish. We would then fill our containers and begin the arduous trek back to the villages built high above the flood lines. With our vessels full of water, we’d trudge, careful-footed, pulling ourselves and the water uphill in a determination for life. Life for the elders whose joints have been ground by the journey before us. Life for the garden. Life for the chickens and goats. For cooking our meals, for washing the rest of the day. For drinking and filling ourselves when the sun is high and awake.

Umunnoho is a tropical rainforest village in southeastern Nigeria. A place older than memory where I spent my formative years. My parents were born at the formation of the post-colonized nation of Nigeria, in a generation of civil war survivors. A generation who grew up in one world that was quickly swallowed by a bigger, greedier one. Youth whose parents’ lifestyles, they believed, lacked the glamor of globalized desires: a Western education, medicine, processed foods, readymade clothes, indoor plumbing, and—most of all—money to buy it all. When what you want can only be bought, you need money and ways to earn it. So we fled, leaving the villages for education, to find jobs, and to earn money. A pied piper of sorts—this dream of a better world, a better way.

How to survive standing in living water: Come back to your body. Remember that you are also water, Water pulsing around an anchor of bones, Enveloped in viscera.

Now

These days I live in Honolulu, on a mountain one mile high. Some mornings, when nostalgia aches, I wake before the sun to trek to the bottom of the hill and stare at the unforgiving concrete pavement of what was once Wai`alae Stream. If there is any water in it, it is the remnants of rain from the night before, waiting stoically for the sun to rise and to be metamorphosed. In those moments, I feel like an alien creature shocked to find itself in a not-so foreign land. Full of commodities and no easy access to free, fresh water.

These days I cover my mouth in company. To catch my breath, fetch the moisture leaking out of me. Stopping, protecting, isolating it. Back in my village, my cousins, who migrated to Europe decades ago, have built a fence around our ancestral compound. All the way from Amsterdam, they built walls around their birthrights. The land is now a commodity: something owned. The paved roads leading to the villages are lined with unfinished mansions rotting in the tropical air, seeping into them, expanding and contracting in the African heat. You can trace the water’s path by following the mossy trails down the cement bricks of half-tumbled walls into the wild earth. Half-realized dreams of diasporic descendants hoping to one day be reunited with the bones of their ancestors who have since released all their water back into the untamable ground. A few days ago, I spoke with two friends about the idea of wild water. One mentioned she only encounters wild water while camping. The other has her own water-catchment system and is off-the-grid. Aside from worrying about toxins in the roofing material of her home poisoning the water, she hasn’t yet had to worry about whether or not she will have water. She lives in a system of abundant water. But as ideal as this is, it still relies on initial capital to make it a reality. Regardless, the three of us agree that this was the best way forward. I remember the dash to set out pails and buckets when it rained in the village to catch water. Especially memorable was the sensation of watching each droplet bounce and create a ripple that cascaded with other ripples—a mesmerizing and hypnotic vision, even in memory. I remember the joy of filling all our basins and knowing the crops and animals, ourselves included, would be nurtured. Moreover, I remember the relief of not needing to trek to the river for a few days.

In Between

For a long time after leaving my village in Nigeria, I lived in major metropolises: Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Boston among them. Now, living in Honolulu, I can almost tell the difference in water… almost.

When you are enshrined in nature, it is easy to think that there has been a mass-deception of people to believe they have to rely on capitalism to survive. The truth is, in the belly of this tower of Babel we are building—this edifice of concrete and steel—there is no choice. Those who subsist far away from nature have to get their resources piped to them. Unfortunately, the feeding tubes come with their palms up, demanding compensation; and the exchange is more abstract than a trek downhill to a river and back up.

Even here in the beautiful Kingdom of Hawai‘i,1 where water falls wild and clean from the sky. On these lands that were nurtured for generations by Indigenous Hawaiians, where water catchment is legal and encouraged; I still pay for water to be piped a mile uphill. Because, although I live in paradise, I do not own a home and do not have the funds or permissions to obtain nor install a water-catchment system. I cannot afford to call any land mine. Yet the whole world is my home and I feel immense responsibility for it. An anxious, suspended existence.

As a child, I fetched water for the elders in my village because they had paved the paths before us to get to the rivers and streams. The older I get, the more I think about this: What pathways have I paved so far in my life? The scarier question, have I even paved any at all; or worse, continued down a path I know leads to risks of poisoned water?

The United States Navy Red Hill Bulk Fuel

Storage Facility is a few miles from my home and is in the middle of a drinking water pollution crisis. Their leaking fuel containers are located less than one hundred feet above aquifers that supply more than 75 percent of the freshwater used on the entire island of Oahu.2

On the other side of the planet there’s an echo and it is of the massive oil leaks and pollution that destroyed the rivers of the Niger Delta region of Nigeria by the Royal Dutch Shell oil company and the subsequent political execution of environmental activist Ken Saro Wiwa in 1995 by Sani Abacha—a kleptocrat dictator.3

A decade ago, I visited Nigeria with my siblings and while taking a walk, we found a live fish in a puddle in the middle of the road. Miles away from any river. For a while, it seemed like a riddle. It wasn’t until much later that we witnessed convoys of lorries hauling loads of sand from the riverbanks to building sites across town. It seems even rivers that haven’t been destroyed by massive oil leaks cannot escape the effects of modernization.

Future

These mornings, I collect dewdrops from my houseplants. I keep them in a tiny vial, and nobody—including myself—knows why I’m doing this. There is no deep meaningful reason that I can access in my psyche, except that it makes me happy to see these dew drops when I wake up. My impulse to collect them feels raw, wild.

I can’t help but think that every time humans have tamed forces of nature, the lasso used to wrangle it entangles us further into a web of co-reliance that is ultimately uncontrollable. Nature as a commodity compounds already complicated relationships between humans and their unquenching thirst for power and greed, as we humans are also wild things that act for the betterment of ourselves over the global good.

The last time I was in my ancestral village, a neighbor came to ask my aunt and uncle to build a gate for them to walk through the compound so that they could continue to follow the old paths to the rivers. Asking us to release our stubborn nostalgic grip on everything we grew up loving: all the treks at dawn filled with laughter and straining, all the joy of communing with family and neighbors, the shared struggles, and the feeling of belonging to a boundless, ancient system. They came to ask us to open the cage we had built around it all. So that they—who don’t just visit but live in the villages still, who walk those paths daily, who keep it paved for future generations—may live. Begging that their lives not be suffocated by the detritus of the unsustainably globalized world that caused us to flee in the first place. ○

Notes

1.

Rachel Edwards