12 minute read

PLANTING FOR FUTURES PAST

An Interview with Oliver Kellhammer

In 2002, ecological artist, educator, activist, and writer Oliver Kellhammer began planting trees in his yard on Cortes Island, British Columbia. His experiment—now a decadeslong botanical intervention called Neo Eocene focuses on the adaptability of prehistoric trees, types that made up the area’s Eocene forests millions of years prior. To develop insight about forest adaptability and how to help the environment develop climate survival strategies, Kellhammer has continued this planting project ever since. Tracking progress along the way, he scaled up in 2008 when he began to plant a grove on sixty acres of clear-cut land.

Advertisement

The following conversation explores the project's trajectory from the Eocene to life beyond the Anthropocene. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What sparked your curiosity about the forest planting that you're working on?

I am an artist who has worked with landscape since the 1980s when I was living in British Columbia in this beautiful rainforest where there was a lot of logging going on. Anybody who lives in the Pacific Northwest knows about these huge clear-cuts, where these old growth forests get logged off which leave bare areas that get reforested by industry. They tend to be monocultures. So, I was aware of that. I had been living in that area for a long time. And there's this specter of climate change: we are experiencing anthropogenic climate change where temperatures are forecast to go up four degrees Celsius, which is a lot, in a hundred years. We're already on our way to two degrees Celsius within the short term. The temperature's getting hotter, and yet we've cut all these trees down and we're replanting the forest with the same trees that were there before. I was interested in asking, is this a good idea? And as an artist who uses my imagination a lot, what would be a more interesting thing to do?

I came upon this concept of bringing back prehistoric trees, trees that had grown in the area during the last period of global warming or intense global warming, which was fifty-five million years ago. I thought if I could figure out what grew back then and bring those trees back, then maybe the landscape could adapt itself to the effect of global heating or climate change, more sustainably and less violently.

What are some of the tree species that you started planting, and how did you choose those specific species?

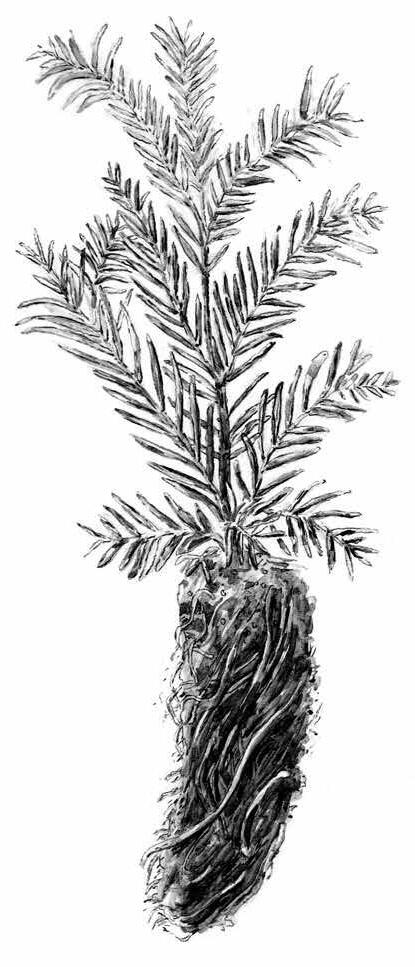

In the environmental movement, we're very concerned about bringing in a species from elsewhere to a place where it shouldn't be. The trees that we chose were prehistorically native, so they weren't never there. They just weren't there recently. Fifty-five million years ago, there weren't any human beings around, so we have to rely on the fossil record. The area of Cortes Island, where the main project is, does not have sedimentary rocks, but maybe less than a hundred miles away are areas with extensive deposits of fossilized leaves of trees—perfectly preserved fossils of California redwood, like coast redwood, sequoia, dawn redwood, Ginkgo, and other trees that don't even exist here anymore. The climate had more diverse forests because it was a lot milder, so we went to look for species that were prehistorically native and for which we had some kind of evidence that they grew there during the last intense period of global warming. Sometimes we couldn't get the exact species, but we would get a close relative.

There was thought given to what would be likely to survive in an unmaintained area. If you have a garden, you can weed and water, but if planting in an industrial clear-cut you're gonna have to plant things that are gonna make it, so really delicious leafy things might not if there's heavy deer browsing. We chose species that we thought would be robust enough to take being stuck in the ground and forgotten about.

British Columbia during the Eocene had a more tropical climate, which hasn't yet changed back to that state. How did the plants that were adapted to a more tropical climate fare in your current iteration of this project?

Nobody knows what the climate's gonna do, other than get hotter. On the West Coast, it seems to be headed toward drought and forest fires. In the Northeast, we’re getting more hurricanes and rain—too much in many cases. Planting a wide variety of species is a strategy— if certain plants like wet summers they should do better, or plants more tolerant of drought and fire that like more heat or more winter moisture should do well. As it turned out, the climate of that area is getting hotter and drier in the summer and wetter in the winter, so species that like summer rain did not enjoy what was happening.

There were also record droughts after we planted the trees, so many survived, but they didn't grow much and more than a few got chomped down because they weren't being tended. There are more extremes now, there's more chaos in the system. In the Eocene, it was more subtropical in a sense—it would be a little bit like northern Florida or that kind of humidity, with much more rain in the growing season. The trees back then were far more diverse and the winters didn't really get much frost by the looks of things, and they're still getting some frost now. So, we didn't really plant super tropical stuff, although some palm trees are hardy in that area.

We hedged our bets and went for a wide spectrum. Now, as it turned out, the trees that did the best hands down are the coast redwood because in California they're getting set back by forest fires and drought. In coastal British Columbia the climate's getting drier, and the coast redwood is more tolerant of summer drought and winter rain. They're also able to feed from fog.

The other species that did quite well was the black walnut, which is now native to the Northeast, but there were similar, prehistoric walnuts once found in the West. Walnuts seemed a good candidate for survival because they have a deep tap root. They can get way down. The sequoia did reasonably well too on certain sites: gravelly, not too much moisture. Those three were the winners and some of the other ones like the Gingko, which we had high hopes for, were not so good. Dawn redwoods, which are a living fossil rediscovered in China in the 1940s, were killed by beavers but did spectacularly well elsewhere on the island. Details matter—anybody who is a professional tree planter will tell you about microsites. It really depends on exactly where a tree is planted on the land.

Assisted migration, like you mentioned, can be perceived as the planned transportation of non-native species. How have you entered into that dialogue with this work?

When we started that work, it was much more controversial than it is now. In fact, there were the people who held the covenant on the land that were very opposed to what we were doing— we had to cut a deal with them to only do it on 30 percent of the land and not the whole property, even though it was all deforested. But now there are many similar projects happening here in the United States, like in New York where they are planting large test plots of trees from just a bit further south. Folks who are responsible for urban trees, like street trees, are no longer choosing historically native trees: in Massachusetts, the iconic New England tree is the beautiful sugar maple, but they're not planting those much anymore because they suffer with the increasing summer temperatures that exacerbate the urban heat island effect. They're planting trees from the Appalachians, Central South, the Mid-Atlantic, and further south—things like sweetgum and yellowwood— that are not recently native here, but have evolved to survive the hotter summers. Native forest lands are not, particularly when they're in stressful situations like urban landscapes. I would argue industrial clear-cuts are also very stressful situations. And where there is stress, pests are attracted and take advantage of the tree’s reduced resistance.

So now there's this serious discussion: Should we move eastern hemlocks further north and bring in more southerly trees? This is being done in various places at scale but the details matter. If you were to bring a tree from Kentucky to Massachusetts, or from California to British Columbia, that would be sort of reasonable, but if you start to bring in something completely alien, that has never even prehistorically been in the landscape. . . There was a big issue in San Francisco with eucalyptus trees, for example, because they have never grown naturally in California or in the northern hemisphere. They’re not in the fossil record, they're not native, and turn out to be somewhat invasive. That's where you have to be careful.

And so saying, bring in all plants from anywhere is not necessarily a good idea. But if things were either prehistorically native or were native in adjacent areas that are a little bit warmer, then I think it's fair game. But this is where judgment and consideration of what you're bringing in and where it grows now, comes in. And it is controversial. But my opinion is, we broke the climate so we need to deal with the consequences to the landscape.

I see this as range expansion, and trees can adjust their range. I'm confident in the coast redwood, because I know it grew fiftyfive million years ago in British Columbia. The ecosystem where they are found natively historically is not that different. If you drive down from the Canadian border to California where the redwoods start, just south of the Oregon border, you'll see species that follow the whole range. Douglas fir can be found along with redwood and red cedar, depending on where you go. There are microcommunities that shift in composition as you move north and south.

I think the best strategy is to look at what's growing close by and see if it will grow a little further north, because the thing with the climate is that it too is an artifact. Here we are bringing a tree from California to Canada and planting it. That seems artificial, but climate change is artificial. We broke the climate. Human beings did that. It's not like it just happened on its own. We were the ones who pumped carbon dioxide in the atmosphere through excessive consumption of fossil fuel, although, it has to be said affluent parts of the world have a much higher per capita carbon footprint. I believe that we do have a responsi- bility to try out these assisted migration experiments to see if they work in confined areas—everywhere, but just to see if we can create some beautiful redwood forests in Canada, to replace the ones that are dying out in California. It's possible that the southern part of the range will no longer be viable for some of these trees because of the increased heat and frequency of fires and that’s tragic and horrible. But on the other hand, if there are tons of redwoods growing north of the border— maybe that's something, and the species won't go extinct.

What can you share about the mycorrhizal connections that form underground between these trees as they settle into the land?

We're very lucky, as the owners of the land are Rupert Sheldrake, and his son Merlin, who wrote that amazing book Entangled Life. He is a soil mycorrhizal bacteria specialist who is taking samples and will be doing an ongoing study of this. Implementing my concept was possible only with their generosity and collaboration.

The temperate rainforest is a mycorrhizaldependent forest. The soils are actually not very fertile. If you dig a hole, you'll see glaciated soils; the rain washes out a lot of the nutrients. However, you have these giant trees—how does that work? It's because of the mycorrhizal associates that are actually extracting nutrients and sharing nutrients in the forest.

One of the practices still happening in the Pacific Northwest is industrial scale clear-cutting, and then the slash and topsoil are burned in order to get a quick potassium hit from the ashes, basically incinerating most of the biomass and the all-important mycorrhizal life. That’s like a sugar high: you're feeling tired and eat a chocolate bar and that's good for like, twenty minutes, and then you basically pass out. That's what the forest industry continues to do—and they put bags of chemical fertilizer next to the seedlings they plant which have caused all kinds of health problems for tree planters. So my hope is that the redwoods we planted will have the memory to deal with the existing mycorrhizal life in that soil. So far, it seems, they are quite at home. They seem to be really benefiting from what's already there. And because coast redwoods and sequoias do grow in association with the leftover native plants still on the clear-cut, like the cedar and the Douglas fir, they may be getting inoculated by them—and so they should do just fine.

Next door is a property owned by the famous mycologist Paul Stamets. Paul has been experimenting with introducing beneficial mycelium in mulch form around seedling trees on the land. This is very active mycelium inoculation work but our approach is more passive. I'm really curious to see the specifics of Merlin's research. He has the scientific knowledge to actually find out what the mycelium are doing and what species they are.

This really is a new area in terms of understanding climate change because mycelium is, in many cases, a carbon absorber. So a lot of the carbon absorption of these forests is not just by the trees, but by the ground and it's the bacteria and the mycelium that really do bioaccumulate a lot of carbon and keep it from warming the climate. We're hoping that we can do more research over time, and this is gonna be an ongoing thing where Merlin will take samples and put them in the lab and actually find out what's going on there.

It’s invisible to most of us. Finding out what specific species are there and how they’ve evolved or adapted throughout these different epochs is expansive to think about. The interesting thing about it is that mushrooms have survived climate change before. There were periods of great extinction where there was volcanic eruption or asteroid impacts. There was global darkness. There was no sun and all the plants died, but that’s when the mycelium provided—they could metabolize all the dead plants, all the charred stumps. They could metabolize that and actually create food for stuff that was still around. They are in a way survivors and healers. They can create a scaffold of fertility for things to regenerate after these horrible events come and go.

You come to this work as an artist and a permaculturalist and started this as a sort of bold conceptual gesture. How have your motivations or sensibilities around the project shifted and changed over time?

I never saw it as a particularly bold gesture, but I was surprised at how other people perceived it as kind of controversial. It seemed to me a pretty simple idea, but it is controversial. And now I think the world is kind of catching up to these ideas. I mean, often artists do things because we are free to be imaginative and unaccountable to institutions in the same kind of way as others. It’s like, I just approached Rupert and said, “Hey, let's just do this and see what works.” And he happens to be a wellknown scientist, and his son a famous mycologist, botanist, and writer. So we were able to have the freedom to just go ahead, to do it.

Once Rupert agreed, the concept was just a question of raising enough money to buy a whole lot of trees and get’ em in the ground, basically. So the freedom of being an artist is good, but there's a whole tradition of this kind of land artwork. When I first went to New York in 1980, there was a very lovely work called Time Landscape at LaGuardia Place and West Hudson by an artist called Alan Sonfist who had planted on the site native vegetation that would have grown in Manhattan before European settler colonialism. It was very bizarre back then, these abject little shrubs and a vacant lot full of garbage. But I was really moved by it. And now, of course, all these years later, it is a beautiful park with giant trees.

Sonfist planted stuff that the built environment had already obliterated. So it is regarded as a public artwork, but it also functions as a kind of contemplative space where you can meditate on how things change over time. That's why it's called Time Landscape, because you're thinking about time as much as you are plants. So I was always really moved by how plants have this ability to bring us together and give us a sense of stewardship, but they do so much else for us too. I mean, we take care of them, they take care of us, right? This idea of a symbiotic relationship between ourselves and plants—a lot of artists have worked with that over the years.

Joseph Beuys was a big influence on me as well. He did this piece called 7000 Oaks where instead of spending a lot of money on a monument he planted oak trees all through the German city of Kassel with big rocks beside them so they couldn't be taken down. His idea was that these trees are a legacy, that through reforesting a city and bringing back nature, we recreate the commons, as opposed to enclosing more property. Our redwood and walnut forest is not being planted to be cut down like the one that was clear-cut before it. It’s gonna be a kind of museum, in a way, hopefully, for people hundreds of years from now who might come