5 minute read

LIVING WITH AMBIGUITY AND AKEBIA

Invasive Species and Trickster Ecologies

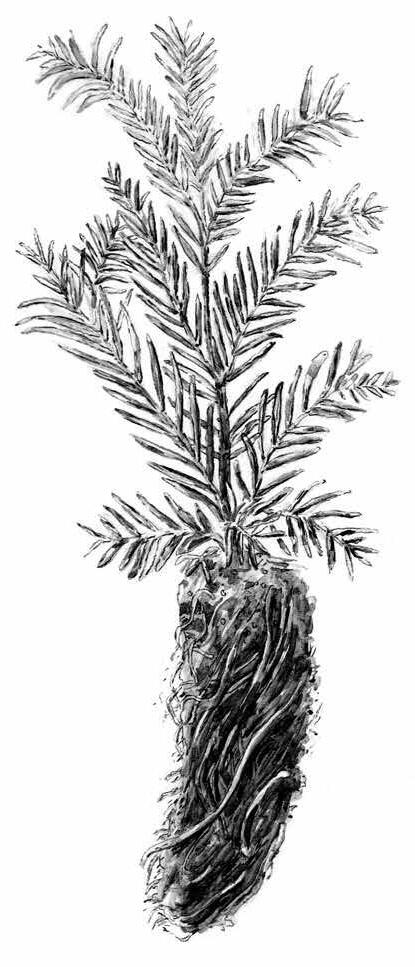

Amid the suburban sprawl of western Guilford County, North Carolina, Guilford College Woods is a 240-acre preserve of mixed Piedmont forest in a sea of commercial and residential development. The Guilford Woods is simultaneously a refuge for local biodiversity and a major host site for invasive species. Among the most pervasive of these is the East Asian vining plant, Akebia quinata, commonly known as chocolate vine for its fragrant, early spring flowers.

Advertisement

The plant was introduced to North America in 1845. Charles S. Sargent, director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum and editor of the journal Garden and Forest, wrote in 1891 that A. quinata was by that time a common plant, “admired for its abundant dark green, digitate leaves . . . and for the abundant and curiously formed rosy purple flowers.” The entry describes the plant’s relatively underappreciated fruit and mentions its culinary usage in Japan, but characterizes it as “insipid” and unpalatable, concluding that “akebia fruit will probably never be valued in this country except as an ornamental.” 1

The 1925 catalog of the Greensboro-based Lindley Nursery Company lists the plant under the “Deciduous Climbing Vines” category. The catalog entry calls the plant a “popular

Japanese climber with beautiful foliage, almost evergreen,” noting that its flowers are “peculiarly shaped” and are produced in April.2 From its introduction into urban and suburban gardens, the plant came to populate local woodlands by its own botanical agency. Today, it is among the most aggressive invasive species in North Carolina and the greater mid-Atlantic, smothering trees, engulfing ground-level and understory habitats in a dense and impenetrable tangle of vine and leaf.

When discussing common control strategies in its contemporary literature on “alien” plants, the Plant Conservation Alliance devotes the bulk of its attention to several possible chemical controls.3 These include various applications of broad-spectrum herbicides, including triclopyr and glyphosate. Such strategies are common in the invasive management world, but raise sticky ethical and moral questions for some of us. Which is doing greater damage in the world—fiveleaf akebia or Monsanto? Is the use of the poisons produced by the latter to eradicate the former an act of love or violence?

David Pellow states that pesticides “are produced for the expressed purpose of killing something, of ending the lives of plants or insects deemed to be invasive or alien.” 4 It can be argued that the logic of pesticide use, whether in agricultural or silvicultural contexts, is about practicing control. By employing the pesticide industry's tools, one is invariably deploying its violent infrastructures. That such infrastructures can be used for ecological simplification (as in the plantation model) or ecosystem restoration (as in the eradication of invasive species) is a rather difficult ontological problem.5 To borrow from Max Liboiron’s harm-violence continuum, the system that produces both the problem—invasive species introduced through botanical commerce and colonialist enterprise—and the purported solution—herbicidal poisons—begets continued systemic violence.6 Akebia creates harms somewhat equivalent to the ubiquity of toxins that harm human bodies.

Perhaps a way out of the competing moral certitudes that such dilemmas generate can be found in what we might think of as trickster ecologies. This perspective applies our present socio-ecological quandaries to the teachings embedded in traditional trickster stories. For our present realities are characterized first and foremost by constant change, contingency, and ambiguity—precisely the domains where trickster consciousness thrives. In various Native American traditions, these stories might revolve around Coyote, Raven, or Rabbit. These figures are often cunning shapeshifters, displaying reckless, vulgar, sometimes foolish, yet generative and adaptive behavior. Trickster stories help us reckon with the uncertainties that challenge rigid human categories in a constantly changing world. Scholars Thomas and Patricia Thornton assert that trickster “remind[s] us of the futility of a managerialism that governs only for control and stability without proper consideration of relational feedbacks and the dynamic and anarchic forces in nature.” 7 As Ursula K. Le Guin characterized the function of Coyote in her own work as a writer of science fiction, “Coyote is an anarchist. She can confuse all civilized ideas simply by trotting through. And she always fools the pompous. Just when your ideas begin to get all nicely arranged and squared off, she messes them up. Things are never going to be neat, that's one thing you can count on.” 8 Rarámuri (Tarahumara) scholar and writer Enrique Salmón explains, “For Native peoples, when we have new plants—invasive species— show up, we don’t think of them in a negative way. We think of them as part of the natural process, and then we come up with ways to incorporate them and adapt to them in our practices and our stories.” 9 This ethic of accommodation, Salmón reminds us, reflects millennia of Indigenous biocultural memory that has borne witness to unending cycles of change and reconstitution of the biotic communities of Turtle Island/Abya Yala. This—in contrast to settler colonial fictions of “pristine” continental landscapes at the time of contact, whose authenticity can and/or must be restored—can serve as an alternative temporal benchmark in our reckonings with the scale of change.

When in bloom, the fragrance of akebia is delicious. Its fruit provides an edible gift, even if one outside of the normative gastronomic repertoire of contemporary North America. It reminds me of the many times I’ve reflected on the place of non-native plants that have become deeply interdigitated in the sensory ecologies of place. The intoxicating fragrance of invasive honeysuckle vine, for example, has been a part of the olfactory ecology of North Carolina and the greater Southeast for multiple generations now. That summer evening perfume is as much a part of that world as anything else. Which all raises the question of how, or if, we might come to love species like akebia. If not love them, then at least tolerate them. Perhaps even ask what kinds of emergent trickster ecologies they might shepherd into existence and what kinds of productive nonviolent relationships we might forge with these newest occupants of our moral and natural landscapes. As crises and shared existential uncertainties mount, these emergent entanglements and biological formations encapsulate a parallel to scholar Michele Murphy’s concept of Alterlife: “Life damaged, life persistent, life otherwise.” 10 Andean peoples recognize this time we are living through as a Pachakuti, a transition between two ages. This is nothing short of a cosmological birthing event: miraculous and painful all at once, full of ambiguity and possibility. Perhaps it is time for a critical revitalization of trickster wisdom to guide us through these terrible and transcendent new becomings. ○

Notes

1. Charles S. Sargent, “Plant Notes: The Fruits of Akebia Quinata,” Garden and Forest 161, vol. 4, (December/January 1891): 136.

2. J. Van. Lindley Nursery Company Catalog (1925).

3. Jil M. Swearingen, Adrienne Reese, and Robert E. Lyons, "Fact Sheet: Fiveleaf Akebia," Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group, invasive.org/ alien/fact/pdf/akqu1.pdf (2006).

4. David Naguib Pellow, Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007): 149.

5. The plantation, as both a historical and contemporary model for arranging human-nature relations, radically simplifies complex natural and social systems.

For example, the plantation replaces complex ecologies and social relations with monocultures and exploitative labor relations that serve the singular purpose of capital accumulation. For further theorization of this concept, see Donna Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin,” Environmental Humanities 6 (2015).

6. Max Libioron, Pollution is Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

7. Thomas F. Thornton and Patricia M. Thornton, “The Mutable, The Mythical, and the Managerial: Raven Narratives and the Anthropocene,” Environment and Society 6 (2015): 66–86.

8. Ursula K. Le Guin, Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences (New York: Roc

Books, 1994).

9. Ayana Young, “Enrique Salmón on Moral Landscapes Amidst Changing Ecologies,” March 20, 2021, in For the Wild, podcast, MP3 audio.

10. Michelle Murphy, “Against Population, Towards Alterlife,” in Adele Clark and Donna Haraway, eds., Making Kin Not Population: Reconceiving Generations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

11. Lucia Stavig, “Experiencing Corona Virus in the Andes,” in Rebecca Irons and Sahra Gibbon, eds., Consciously Quarantined: A COVID-19 response from the Social Sciences, May 2020. medanthucl.com/2020/05/04/experiencing-corona-virus-in-the-andes.