We understand you prioritize your athlete’s safety, as much as their ability to compete. That’s why Gill Athletics® is proud to offer the next generation of throwing cages, because it keeps the focus where it belongs.

• Single or Double Ring for the same cost

• Sliding Net Doors

• Single-operator U-NET frame & winch

• 3-Pole Super Structure

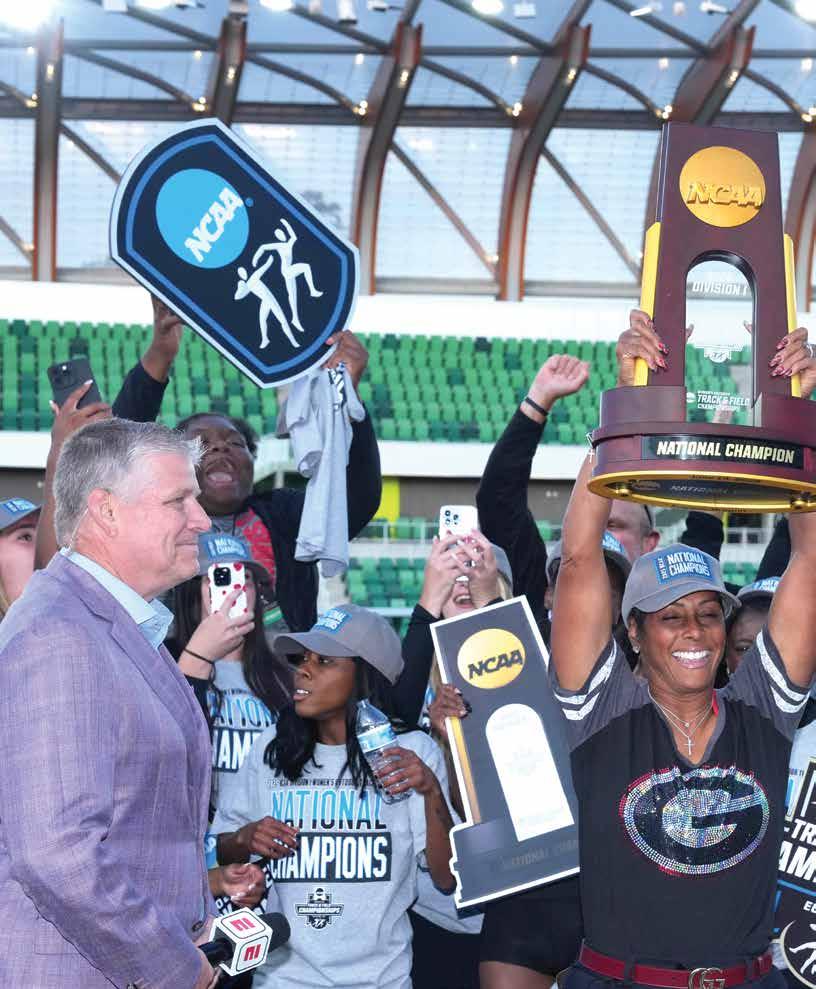

CARYL SMITH GILBERT

USTFCCCA President

Caryl Smith Gilbert is the Director of Men’s and Women’s Track & Field at the University of Georgia. Caryl can be reached at UGATFXC@sports.uga.edu

MARC DAVIS

Track & Field

Marc Davis is the Director of Track &Field and Cross Counry at Troy University. Marc can be reached at mddavis@troy.edu.

TINA DAVIS FERNANDEZ

Track & Field

Tina Davis Fernandez is the Head Cross Country and Track & Field Coach for CAL State LA. Tina can be reached at Tina.DavisFernandes@ calstatela.edu

CHAD GUNNELSON

Track & Field

Chad Gunnelson is the Director of Track and Field and Cross Country at Augustana College. Chad can be reached at chadgunnelson@augustana.edu

CALEB SNYDER

Track & Field

Caleb Snyder is the Head Men’ and Women’s Track & Field Coach at Indiana Wesleyan University. Caleb can be reached at caleb.snyder@indwes.edu

CHIP GAYDEN

Track & Field

Chip Gayden is the Head Men’s and Women’s Track & Field Coach at Meridian Community College. He can be reached at hgayden@meridiancc.edu

STEFANIE SLEKIS

Cross Country

Stefanie Slekis is the Head Coach of Track and Field and Cross Country at Nicholls State University. Stefanie can be reached at stefanie.slekis@nicholls.edu

PUBLISHER

Sam Seemes

MEMBERSHIP SERVICES

Nick Lieggi, Samantha Morse, Kristina Taylor, Dave Svoboda

COMMUNICATIONS

Garrett Bampos, Tom Lewis, Tyler Mayforth, Howard Willman

PHOTOGRAPHER

Kirby Lee

EDITORIAL BOARD

Tommy Badon, Scott Christensen, Todd Lane, Derek Yush

ART DIRECTOR

Tiffani Reding Amedeo

PUBLISHED BY

JAMEY HARRIS

Cross Country

Jamey Harris is the Head Men’ and Women’s Track & Field Coach at CAL Poly Humboldt University. Jamey can be reached at jamey@humboldt.edu

RYAN CHAPMAN

Cross Country

Ryan Chapman is the Head Coach of Men’s and Women’s Cross Country at Wartburg College. Ryan can be reached at ryan.chapman@wartburg.edu

Renaissance Publishing LLC

110 Veterans Memorial Blvd., Suite 123, Metairie, LA 70005 (504) 828-1380

myneworleans.com

GRIER GATLIN

Cross Country

Grier Gatlin is the Head Coach of Track and Field and Cross Country at Southern Oregon University. Grier can be reached at gatling@sou.edu

DEE BROWN

Cross Country

Dee Brown is the Director of Track and Field and Cross Country at Iowa Central CC. Dee can be reached at brown_dee@iowacentral.edu

USTFCCCA

National Office 1100 Poydras Street, Suite 1750 New Orleans, LA 70163 Phone: 504-599-8900 Website: ustfccca.org

If you would like to submit content for, or advertise your business in Techniques, please contact 504-599-8906 or techniques@ustfccca.org.

Techniques (ISSN 1939-3849) is published quarterly in February, May, August and November by the U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association. Copyright 2025. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner, in whole or in part, without the permission of the publisher. techniques is not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts, photos and artwork even if accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. The opinions expressed in techniques are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the magazines’ managers or owners. Periodical Postage Paid at New Orleans La and Additional Entry Offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: USTFCCCA, PO Box 55969, Metairie, LA 70055-5969.

Solving

There are a myriad of challenging problems and issues that confront a coach that is responsible for the training of hurdlers in both the long and short hurdle events. Most coaches understand there are many different, but equally successful methods of training hurdlers. Most coaches also understand that there are different ways to approach hurdle issues, but ultimately, they will have to be problem solvers and ”Mr. Fix It” if they want to be a successful hurdle coach.

The objective of this article is to explore and offer coaches the methods (most of them very practical) utilized at the University of Mary (Bismarck, ND) to solve some of the more problematic issues in the coaching of the sprint and intermediate hurdles. We will offer corrections, observations, thoughts, drills, insight, coaching cues, philosophy and principles that can all be applied to the successful “fixing” of some of the major concerns. We will outline our “fixes” for the different matters we dealt with, as well as problems presented to us from a survey of coaches and both current and former hurdlers.

Some of the concerns are common to both the sprint and intermediate hurdles. Some are unique to just one event or gender. We certainly acknowledge that there are many ways to solve these problems, but we offer what has “worked” for us. We certainly made plenty of mistakes and had numerous failures as our training evolved. Our training was in a constant state of change…what we always called “change with a purpose.” Most of our trouble-shooting solutions were made though experimentation and by trial and error, and we turned many mistakes into learning opportunities. Not all our solutions were science-based and common hurdle theory. In fact, much of our training and problem-solving was very empirical in nature, based on our observation and experiences with our athletes and the environment we trained in.

One of the things that was very interesting and will be addressed later in this article was the differences in what coaches and athletes perceived to be “major” concerns. Without further ado, let’s get into the hurdle concerns.

PROBLEM 1: CORRECT HURDLE RHYTHMS.

Our survey revealed that many of the coaches felt their number one issue was obtaining the correct hurdle rhythms. The author couldn’t agree more. You are what you train is not a cliché. It is a fact. Many coaches do not obtain the desired hurdle rhythms simply because they don’t train it! They know what needs to be trained, but they just don’t know the how. What can be done to obtain the desired hurdle rhythms? A lot. And there are differences for men and women. Before we move forward with the specifics, coaches must understand our primary objective in our hurdle program: Train to the specifics of performance. Train fast and do the training that translates to being FAST! Training should mirror performance. I have always liked the quote by the late Dr. Ralph Mann, a former world class 400 meter hurdler who was a leading authority in biomechanics, talking about this subject, “Good coaches understand and teach to the science of performance,” he noted. In our case, this was manipulating the spacing and hurdle heights to obtain competition hurdle

rhythms and speeds despite there being a 5-10 percent drop in training intensity compared to competition. It is critically important that the correct motor patterns be repeatedly rehearsed to obtain the desired race model. The old cliché about “practice makes perfect only if practiced perfectly,” certainly applies here. The reality is practice makes permanent. A way to monitor and gauge the hurdle rhythms you are seeking: touchdown times and charts.

Some of the methods of obtaining race repetitions in training include:

• Discounted spacing. Although some coaches do not believe or use discount spacing, our women never used the standard 8.5 meter distance in training. Our ranges were from 8.0-8.3 meters, depending on the individual athlete. It was what we termed, “progressively reduced spacing.” Our typical spacing for many of our female hurdlers was 8.0 meters. The men’s spacing could vary from 8.53 meters to the standard 9.14 meters, again depending on the skill level of the athlete. The normal training distance for men was 8.84 meters. It is much more difficult to replicate the race repetitions for men

because they cannot realize anywhere near all their speed in the 110-meter hurdle race. Men reach approximately 75 percent of their maximum speed, per Dr. Mann. The challenge for the coach is to arrive at the discount spacing that allows the male hurdler to obtain “race rhythms.” Race speeds for the men are a modified sprint often referred to as a gallop or shuffle because they cannot reach top speed with the “crowded” standard spacing of 9.14 meters. It is much simpler for women where speed is a focal point, and the spacing can be exploited to not only achieve race speeds, but challenge the rhythm to establish an even quicker cadence throughout the hurdles. It should be pointed out, however, that the female hurdlers only really reach close to maximum speed in the approach to the first hurdle and the run-in. But improving speed is, nevertheless, imperative for women. Tapping into the central nervous system (CNS) as much as possible was a guiding principle for both our female and male hurdlers. Our hurdlers benefited from both assisted and overspeed training and coaches need to know the difference between the two. Assisted training is assisting athletes

Beynon controls all aspects of the manufacturing value chain. From start to finish, your project doesn’t leave our hands.

Manufactured and installed with the highest attention to detail, Beynon systems showcase proven durability.

For indoor or outdoor venues, Beynon is the trusted surface of leading NCAA Div I programs, thousands of high schools and distinguished municipal facilities.

Part of Tarkett Sports, a division of the Tarkett Group, a worldwide leader of innovative flooring and sports surface solutions, Beynon has unprecedented financial support and stability. You can rest easy.

to produce speeds they are capable of, but with less effort. Overspeed training is having athletes reaching speeds that they would not have been capable of doing without assistance. The commonality in all great training programs is that speed development is a key component. Absolute speed or maximum velocity training must be on the menu on a very consistent, year-round basis.

• Modified Hurdle Heights Discounted. Hurdling goes hand and hand with modifying hurdle heights. A good percentage of our women’s hurdling was done with 30-inch hurdles. Some coaches decrease further, going as low as 24 inches. The standard 33-inch hurdle was certainly used in training, often for the first hurdle in hurdle repetitions from the blocks. Anything from 33-inch hurdles to 42-inch hurdles (some coaches go as high as 45 inches) were used in the men’s hurdle training, again depending on the caliber of the athlete and what parameters were needed to establish the preferred hurdle rhythm. A large percentage of the training was done at 39 inches. Men employed standard 42-inch hurdles much more than women used the 33-inch barriers because, we felt it was critical for the men to create a comfort level with the much higher hurdle. Many of the men’s drills were, however, done with 36-inch hurdles or lower.

• Fatigue and recovery are obvious factors that the coach must take into consideration if the objective is “race rhythms.” The training programs must be designed to allow hurdlers to arrive at the hurdle sessions basically “fatigue free.” The coach always needs to understand what the desired end product is before planning the training program. The recovery needs to be programmed into the training. Far too many coaches rely on many of the modalities (ice bath, sauna, massage, contrast baths, laser therapy) to take care of the recovery process and don’t allow the body’s natural inflammatory process to dictate the adaptive response. Even within the hurdle practice itself, it is imperative that the proper amount of recovery be allocated. Our rule was one minute per hurdle for any repetition of over 5 hurdles or more. Quite often full recovery (12-15) minutes was taken, especially for the men. Many coaches receive disappointing results in their hurdle repetitions because of insufficient recovery. Another consideration for coaches to account for is how their strength programs work in conjugation with the training, and it also must factor in the recovery assimilation. Quality over

quantity with high intensity was the emphasis in the Mary hurdle training. The men typically did less rep volume and quantity due to the higher energy demands of the 110-meter hurdles. With that in mind, good hurdle coaches are extremely attentive to the hurdle count when designing the hurdle session.

• Teammate Competition. An extremely important ingredient in obtaining race speeds was “competition” hurdling amongst teammates. Our athletes simply lined up and competed against each other in training, pushing, and motivating each other to faster speeds and the necessary hurdle rhythms. Very little of our hurdle repetitions were “solo” runs.

• Posture Problems. Many rhythm problems are the result of coming off the hurdle with poor posture, causing the hips and center of gravity to sink and lower. The hurdler never truly recovers from this lowering of the body, with the athlete failing to raise the hips and chest into good sprint form for the entire three steps between barriers.

From the author’s perspective, take-off efficiency may be the biggest technical difficulty, and our survey coaches and athletes agreed. There are many possible technical errors during take-off, and we have listed some of the major flaws:

• Straight lead leg with knee locked and the foot leading. Correction: The hurdler should have a flexed lead leg, leading with the knee coming straight up to the hurdler’s torso, driving the leg over the hurdle with no swinging. A bent leg lead leg will allow the hurdler to return to the track quicker and reduce airtime. A bent leg lead leg also reduces tension on the hamstring. Most flight and air problems are the result of poor takeoff, which arguably is the most critical aspect of hurdling technique. A good drill for this is the one step hurdle drill where the hurdler has only one step between hurdles that are obviously spaced very close together. (See drill section for the explanation for the drill and all the major Mary drills.)

• Too much forward body lean at take-off. It is of the essence that postural integrity be maintained at take-off. Athletes should be reminded the mechanics of hurdling take place before the hurdle and not at it. Correction: Coaching cues such as “tall hips,” “keeping chest up” and “knee up” with a cocked foot will aid in keeping the athlete in the correct position. Traditionally, many men’s hurdlers were taught to dive into the hurdle. This diving technique and excessive

lean causes the body to rotate down, and the segments in the back of the body to rotate up. This causes a number of undesirable consequences. These issues include dropping the lead leg down and making it difficult to clear the hurdle, excessive height over the hurdle, and it places the hurdler in a poor position upon landing and coming off the hurdle Rather than diving, the athlete should be taught to bring the knee up to the chest. The quick lead knee will result in what is often termed a delayed trail leg where the trail leg gets the desirable full extension at take- off. Some advice from Gary Winckler, a Hall of Fame sprint/hurdle coach, “Leave the trail leg back until you feel the push from the toe. This will cause a stretch in the thigh muscles, which will snap the trail leg through with little or no effort.” To summarize, the correct lean of the upper body will make it possible for the hurdler to minimally raise the center of mass for effective clearance and reduce airtime.

An athlete can encounter many different difficulties as they work to establish consistent take-off at the first hurdle. There are several remedies or combinations of factors that can correct this: (1.) Adjust the block placement in regard to the starting line and move the athlete to a more medium start if they are using a foot placement too close together. (2.) Increase the power output of the first three 3-4 steps from blocks (the first several strides of the hurdle start are nearly identical to the sprint start), accelerating harder and pushing to the designated take-off location. (3.) Use checkmarks and a marker of some sort (tape, cone) to mark the location of the desired take-off. This will assist the hurdler who is both too close and too far away. The range for take-off marks are 1.95-2.10m for women and 2.0-2.20m for men. These can vary depending on the anthropometric factors of the athlete. (4.) The first hurdle can be moved closer to the starting line and then progressively returned to the standard distance as the athlete adjusts and becomes comfortable with the regular distance. (5.) Some elite hurdlers may need to switch from the traditional eight-step approach to a seven-step approach to the first hurdle. The seven-step approach is advisable for taller, elite athletes. Per Dr. Mann, only a male hurdler who is capable of a 13.5 second hurdle race, and a female hurdler who can run 12.5, should consider making the switch. The first three steps are the most important if this approach is to be successful, with the men being at 3.81 meters

Rekortan tracks are known for their balance of force reduction and energy return which delivers speed and athlete welfare.

Over 50 years of experience, Rekortan continues to lead:

Most Olympic Records

Most Diamond League venues

Most certified tracks in the world

Made of 84% renewable & recycled materials

USDA certified products

FEEL THE REKORTAN DIFFERENCE —

Schedule a Track Assessment Today.

at the third step, and women at 3.63 meters by the third step to truly work effectively. Coaches should be aware that switching to a seven-step approach may allow the athlete to reach the first hurdle faster. But it may not set the hurdler up for an overall, successful race. One advantage to the traditional eight-step approach is that the athlete has one extra step than the seven-stepper to generate force and speed. (6.) A soft hurdle or cushioned hurdle top can be used to assist athletes in overcoming fear of hitting hurdles and can allow the athlete to take more risks until they become more comfortable with an aggressive approach and take-off to the first hurdle.

PROBLEM 4: HURDLE CLEARANCE AND LANDING. THERE ARE A NUMBER OF POSSIBLE ISSUES HERE. LET’S GET STARTED:

• Hitting Hurdles late in the race. There are various reasons for hitting hurdles late in the race: lack of focus, improper management of the three- step pattern, too close to hurdle (typically a men’s issue) and overstriding. Corrections: Coming off the hurdle in a sprint position without lowering the body/hips and managing the three steps properly, with a highly active cut step, can be immensely helpful. A lot of energy is lost by lowering the body and then having to reposition. Ground time going into and coming off the hurdle will largely determine success. Men need to utilize a modified sprint rhythm and understand the need for control as they approach the next barrier. Some women overstride in an attempt to get to the next barrier faster and it actually slows their rhythm to the point that they can’t get to the hurdle, usually hit-

ting the trail leg. Athletes need to focus on their race, their lane and not allow themselves to be distracted by other competitors and lose concentration. Multiple athletes that completed the survey commented that one of the things that assisted them in focusing was visualization techniques taught by their coaches. Video was also frequently mentioned as an excellent teaching tool that athletes found especially useful.

• Improper sprint mechanics through and over the top of the hurdle. Taking the start from the equation, the hurdler who can produce the greatest amount of horizontal velocity and maintain it over the hurdles will be the most successful. Balance issues, hesitation, or a pause with the arms, sitting on top of hurdle, and landing incorrectly are some of the reasons that this doesn’t occur. Some fixes: (1.) Athletes should be instructed to run through the hurdle with basically the arm mechanics of a sprinter, with the men using a slight deviation with the lead arm by bringing it up and slightly higher and to the middle of the torso than regular sprint mechanics. There should be as little deviation from normal sprint mechanics as possible! Velocity through the hurdle is critical to elite performance. (2.) The proper tall take- off position, leading with the hand and good sprint posture, will dictate landing efficiency and allow athletes to “run off” the hurdle. The arms must be continuous with no lapse or pause over the hurdle, with the shoulders square to the barrier and in alignment. Two things that cause excessive lateral rotation and balance issues are the arms crossing the midline and a swinging of the lead leg. A coaching

cue: Instruct the hurdler to “square up the shoulders” to the hurdle. One of the drills that we found useful to curb this issue was our arms drills (misnamed because you can’t use arms) which we describe in the drills section. (3.) Extreme sweeping of the trail arm should be avoided. The trail arm should return to normal sprint mechanics as soon as possible, avoiding the long, exaggerated sweep backward. It is very time-consuming and inefficient. Our athletes were advised to keep sprint mechanics in a so-called “sprint box” (an invisible paperclip shaped box framework if you are envisioning the parameters) and not to reach with either the lead arm or trail arm, never allowing the arms to get out of the box, so to speak. (4.) Hurdlers should be urged to come off the hurdle with good posture and land on the forefoot, with the foot under the center of mass. The down step landing in a braking position will undoubtedly cause the athlete to encounter rhythm problems to the next hurdle. Ground time going into the hurdle and coming off is what really will determine hurdle success. Ground time is established by how quickly the hurdler can generate the explosive ground forces at precisely the correct time to successfully project the body over the hurdle, and then control the following touchdown.(5.) An opening up of the trail leg too quickly will cause balance problems. The hurdler must not rush the trail leg. The trail leg must be kept folded until the thigh has reached a position where the knee is pointing in the direction of travel before opening up toward the ground. (6.) We often used weighted hand gloves (1 to 2 pounds) to control arm mechanics and teach good, aggressive arm amplitude. Most of the time we enlisted weighted gloves on both hands, although at times we would use just one if needed to correct a flaw that did not involve both arms. In another scenario we used a heavier weighted glove on the less efficient arm. Many coaches have dismissed our hand weight use, calling it a gimmick unsubstantiated by science. Call them what you want. We started using them with high school athletes over 40 years ago and we used them successfully throughout the years with age groups ranging from middle school to elite. We have always called the hand weights a form of functional training that employs the “overload” principle similar to using a “weighted donut” on a baseball bat to increase bat speed. We have always said that coaches should be creative, experiment, innovate rather than imitate, and not be afraid to push boundaries. Coaches should never be appre-

hensive about going against conventional thinking. (7.) Taking off on the heel typically results in the hurdler going too high over the hurdle and not returning to the track with the proper touchdown distance. Normal touchdown range is 0.80-1.0 meters for women and 1.15-1.30 meters for men.

A breathing model/control pattern is something that is often overlooked, but can certainly contribute to the enhancement of sprint rhythm maintenance and endurance for the hurdler. The hurdler will establish a specific pattern of breathing in the race, with the hurdler “blowing out” on hurdles 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and holding their breath the remaining time. The breath should be held into the set position. Many elite hurdlers use a pattern of “blowing out” on hurdles 1-4-7-10. Holding your breath creates what is known as the Valsalva maneuver, which research shows increases blood pressure in the carotid artery, facilitating motor unit availability/recruitment. It is important to “recharge the system” because studies have shown that sustained maximum motor firing even for very elite athletes can last for only approximately 2 ½ seconds. Our experience has been that athletes will need to take a progressive approach to this issue, beginning with one or two breaths and increasing incrementally.

400M INTERMEDIATE HURDLE PROBLEMS PROBLEM 1: RACE ADJUSTMENT/STEERING.

This was the number one priority in the minds of the 400 meter hurdlers who responded to the survey. They said their number one issue was having both the mentality and fitness levels to make the needed race management adjustments, especially late race modifications. A lot of things can be done to assist athletes in this area. Let’s look at a few:

• Drills that force the athlete to adjust. We have listed some of the exercises in our drills section that influence athletes to make adjustments. There are several coaching cues that can greatly assist the hurdler. Two in particular: (1.) Speed up and accelerate aggressively the last three strides into the hurdle, carrying momentum over the hurdle. (2.) Focus and make adjustments well in advance of the hurdle, rather than stuttering and slowing down on approach right before the hurdle.

• Confidence. An important role of the coach is to instill confidence in the athlete that they can use both legs successfully, either the preferred or non-preferred lead leg. The

mentality that an athlete possesses will greatly determine the ability of the athlete to manage the race effectively.

• Race fatigue. Athletes must learn to deal with race fatigue and what Coach Winckler calls “coping strategies” in training. Numerous repetitions over different segments of the race that will challenge the hurdler to deal with “competition fatigue” in training are a real key. Fact: The best 400 hurdlers maximize their non-fatigue velocity while limiting the loss of velocity in the fatigued state.

• Turn work. Many of the adjustment/ steering matters occur on the corner, especially the number seven and eight hurdles that seems to be problematic for many hurdlers. Doing a lot of drills on the curve using hurdles 6-8 proved to be very beneficial for our program. A simple drill where the athlete did reps over hurdles 6-8 at race pace and then jogged back with low recovery to repeat was particularly challenging and effective. The athlete was forced into hurdling on the turn in a fatigued state. Another excellent and very demanding exercise was shuttle hurdles on the turn.

• Balancing training. It is important to strike a balance between training with fatigue and making adjustments with obtaining as many race reps with the established stride pattern as possible. Excessive fatigue that forces the athlete to switch to different stride patterns than what will be used on race day should be discouraged.

PROBLEM 2 FIRST HURDLE PROBLEMS. A successful first hurdle clearance is critically important to establish the tone for the race, and ultimately the success of the athlete. First hurdle success is undoubtedly extremely important for the overall positive mentality for the athlete. We have addressed some first hurdle problem areas below.

• Inconsistent Approach. Correction: A number of things can be done to alleviate the inconsistencies, but the number one solution is repetitions and a lot of them. Repetitions in all different kinds of weather in different lane choices. Hurdle touchdown times need to be consistent and always monitored. Close attention, too, must be paid to block settings and where the athlete is running in the lane.

• Establishing a First Hurdle take-off. A useful tool to determine the number of strides to the first hurdle is to put a mark on the track at approximately 43.40 meters from the start and have the athlete attempt to hit it with the desired takeoff leg without a first hurdle present. Tape or some other item can mark the

location of the first hurdle at the standard 45 meter mark.

PROBLEM 3 RACE MANAGEMENT RHYTHM AND STRIDE PATTERN PROBLEMS. The 400 hurdles are a rhythm race and there are many factors that dictate race management mastery. They include hurdle clearance, stride length, fitness levels, hurdle efficiency, lane positioning, and adverse conditions such as wind and cold. There are numerous problems that can occur, and we look at several:

• Inablity to alternate. Correction: A left leg lead leg is certainly desirable for obvious reasons, but athletes will have to be taught to alternate to conquer quality race management. A quote by the late Ralph Lindeman, a very knowledgeable hurdle authority who was at the Air Force Academy for many years, speaks to this, “The most valuable technique you can teach a 400 meter hurdler is the ability to alternate consecutive legs.” The ideal stride pattern would be an odd number of steps between all hurdles. A 13, 15, 17, 19 stride pattern assures that the hurdler will take all the barriers with the same lead leg. An even number stride pattern will force the hurdler to alternate consecutive hurdles. Athletes should be required to use both legs in training drills and race tempo preparation. The coach should design drills and set spacings to “ force “ the athlete to use both legs. Many athletes will not use both legs unless strongly influenced to do so in training.

• Improper tempo/rhythm speeds. Correction: The normal sprint stride will not work well in the intermediate hurdles for most athletes. With that in mind, a great deal of the speeds in training must be the tempo hurdle pace and speed that the hurdler will utilize in the race. “There is no value at training at less than race speed,” said Coach Winckler, addressing this subject.

• Distribution Problems. Correction: Very un-even and inconsistent paces will invariably cause problems for the 400 meter hurdler. Coaches and athletes alike must understand that correct distribution is a key to success. A quite common problem is that athletes start the first part of the race much too fast and the result is that the second half of the race suffers dramatically. Again, as in a lot of areas, touchdown times and 200m split times are a great method of tracking distribution. Intermediate hurdlers, too, must understand that their race is remarkably similar to the open 400 meters in dispersal of energy. We have always told 400 hurdlers this: “You need to be a great quarter miler if you are

going to be a great 400 hurdler. An average 400 runner is a very average or below average intermediate hurdler.”

• Adapting to Adverse Conditions.

Correction: Athletes must train in all types of weather and conditions (especially wind) if they expect to have the ability to manage their event on race day. Wind and cold obviously can have a very adverse effect on stride patterns. Training should also be done using all the different lanes, even less preferred ones.

• Meet Inexperience. Correction: There is no substitute for competition. The best training for the 400 meter hurdles is to actually experience the race in competition as often as possible. Although the 400 hurdles are one of the “toughest” races on the track, my advice to young coaches, “Race your athletes often.” Within reason, of course, but the athlete needs to experience the race frequently.

PROBLEMS. Successful 400 hurdlers always have good hurdling skills with either leg and excellent sprint mechanics. Inferior hurdle and sprint mechanics will make the 400 meter hurdles much more difficult. Athletes must understand that hurdling is sprinting. An athlete can only be as fast as their mechanics will allow, and because they can be such a limiting factor, excellent sprint mechanics are critically important. Again, to quote Dr. Mann, “Putting the body in the correct position, at the proper time, with the body segments moving in the right direction and speed, is the only way to maximize potential.” A couple of our thoughts: (1.) There should be a year- around emphasis on sprint mechanics. Coaches should not allow sloppy and subpar mechanics. Period. The proper sprint mechanics need to always be closely supervised. (2.) Sprint efficiency is more important in longer races than it is in shorter events because you are covering longer distances and taking more steps. (3.) It should be stressed to athletes that improving your foundation of strength can noticeably improve sprint mechanics.

• Speciality 400 hurdlers. Athletes typically competed in both intermediate and sprint hurdles in years past. This is no longer true, and our observation is that hurdlers that exclusively specialize in the 400 hurdles do not always have all the required hurdle skills. Correction: The exclusive 400 hurdler should be required to increase their volume of drill work on a consistent basis, again emphasizing the use of both legs. A steady diet of short tempo work with irregular spacing should be

a training staple. Technique work needs to be done on a consistent, weekly basis, even in the Fall training phase.

One of the biggest dilemmas in training 400 hurdlers is designing a systematic training program that blends and balances all the necessary components (including strength programs) for success while allowing the athlete the proper recovery and adaptation time.

• A balancing act. Correction: The various energy systems should be trained concurrently instead of in isolation. Our program moved away from periodization, per say, as a model (periodization was never intended to be a model; it is a concept) and the training blocks that had a single-minded concentration many years ago. It is a deep- seated flaw to isolate training systems, which in the past was often the norm and continues still in some coaching circles. Although certain energy systems will obviously need more emphasis or concentration, our focuses were on speed endurance and absolute speed. We always kept in mind the training gems that Dr. Mann always spoke of in his book entitled, “The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling” that he co-authored with Amber Murphy: (1.) Improvement in fatigue velocity provides the best way to increase performance in the long hurdles. (2.) One of the best ways to improve non- fatigue velocity in the long hurdles is to improve maximum velocity of the athlete in the short sprints. Like many coaches, however, we neglected pure speed or absolute speed as a young coach. Big mistake. Absolute speed is essential for the 400 hurdler!

• Incorrect programming. Coaches have constantly asked throughout the years if they could obtain some of our so-called “great” workouts. Like many young coaches, I just wanted someone to give me a “cookbook” during my first few years of coaching. The problem is, I didn’t even know “how to” cook. No number of cookbooks could possibly help. My response when asked for our training has always been, “Of course, I can pass on some of our better workouts. But they really wouldn’t do you much good.” Why do I say that? You must always have context with any kind of training before adopting it as your own. Workouts do not make an athlete great. Do they help? Certainly. But copying a workout that is not appropriate for the athlete does not usually lead to success and risks injury. The true secret in successful training design is sequencing together with the proper progression the appropriate methodologies

and dosages that fit the particular needs of the athlete. I often tell young coaches,”It isn’t so much what you do, it is a matter of when you do it.” There is a time and place for each training component and a lot of different pathways on the road to success. It is much like fitting all the pieces of a puzzle together. An improperly placed piece can cause some serious problems. Many coaches are like a small child who is attempting to fit together a puzzle that is not age appropriate. They struggle piecing training together the way a small child would struggle with a thousand piece puzzle. They can’t fit it together correctly. Training design is much the same way. The pieces must fit together in a framework that is appropriate and sequential to be effective and successful. There are many, many layers of successful training and it is the coach that must work through the layers.

It was remarkably interesting to note that what coaches thought were major concerns weren’t even on the radar of some of the athletes who answered the survey. The chief concern for the athletes, both male and female, was the relationship with their coach and how their mentor could instill confidence in their abilities and ultimately guide them to success. The athletes thought that communication skills, honesty, constructive feedback, and an understanding of the athletes’ needs were much more critical to success than solving technical issues.

“We felt our coaches understood their athletes and empowered them to do the tasks at hand,” said Marsha-Gaye Knight, a Jamaican athlete who was a conference champion in the hurdles for the University of Mary.

“The importance of building and trusting in your coaches was extremely important,” commented Tereza Bolibruch, a conference champion sprint hurdler from North Dakota State University in Fargo, ND. “Knowing that the coach truly cares about you as a person and not just as an athlete is very, very important,” she added.

“I really responded to the Mary style of coaching that provided encouragement, motivation, feedback, and individual attention,” said Josh Lamers, an All American hurdler at the University of Mary after transferring from LSU.

We have always said that coaching is really about relationships and creating an environment where the athlete can be successful on and off the track. It is the role of the coach to lead the athlete to positive outcomes in both

areas. The survey certainly proved this to be absolutely true.

Contrary to what many people believe and have said, drills were a fundamental part of our hurdle program, for both men and women. Do coaches “overdo” drills and buy in to the “monkey-see, monkey do” syndrome? Certainly. That has been our viewpoint for many years. Especially the very slow drill work that does not transfer to competition hurdling. There is a semantics issue, too, with what many coaches term “drills.” We have always classified anything that does not involve full speed hurdling as drill work/exercises. So, did we do drills? Yes indeed. Both genders, with the men obviously doing more due to the 110 meter hurdles being a much more technical event. Technical flaws are most certainly magnified for the men due to the hurdle height. Our advice on drills is to limit them to what is absolutely necessary, and avoid the less active, slower movement ones. I always tell athletes and coaches this, “Do the drills that have the highest degree of transfer possible.” I have always liked Vern Gambetta’s take on deciding what your training should be: “Is what I am doing nice-to-do or need-to-do? If it is not need-to-do, don’t do it,” says the former track and field coach who is considered the

founding father of functional training. “From my experience,” added the legendary coach, “nice-to-do activities make you feel tired and hurt; need-to-do makes you better and helps you advance toward your training and competition goals.” Our Mary drill philosophy: The drills should be done at the highest possible velocity possible, emphasizing front-side mechanics that reinforce force mechanics. Only drills that really translate to fast hurdling and race rhythms should be in the coaches’ repertoire. None of the Mary drill work was done on the side of the hurdle, with all drills done “over-the-top.” One of our major reasons for limiting drill work was to “save” the athlete’s energy for the race rep portion of the training session. A wise axiom from the late Dr. Mann to keep in mind, “Athletes have an average of about two hours a day for performance improvement, and within this time period, the athlete can be stressed at the highest levels for an average of only about three minutes total.” Many athletes, because of the abundance of drill work, cannot produce the energy that is needed to reach race speeds in the primary and most important portion of the hurdle workout. Quality rehearsal should be the focus when it comes to drills. We have listed our major drills that proved to be very beneficial: Arm Drills. These drills are unique to our program and the programs of former athletes

and coaches who have adopted them into their own training protocols. Any number of lower hurdles (30’ or lower for women; 33” for men) can be used for this exercise at discounted spacing for men (8.23m-8.53 meters) and 7-7.5 meters for women, although spacing is not critically important because the drill is done at slower controlled speeds. We always encouraged the use of uniform spacing for sprint hurdlers and irregular spacing for long hurdlers. The drill is misnamed in that the athlete must hurdle at slower speeds (70-75%) without using their arms. There are six versions: (1.) Regular Athlete. Hurdles from a standing start any number of hurdles with the arms extended out in front of the body in a locked position. (2.) Fly. Same as #1 except arms are extended like wings. (3.) Chest. Same as 1 and 2 except arms are held tightly folded to the chest. (Helpful if the athlete grabs shirt.) (4.) Medicine Ball. Same as 1-3 except the athlete holds a med ball extended out in front of them as they go over the hurdle. The weight of the med ball depends on the athlete. Our women used a 2k ball and men 3k. (5.) Arms straight down at sides. Same as 1-4 except arms are held down by pockets at sides. (6.) Arms grasped at back of athlete. Same as 1-5, except the arms are held together and locked behind the athlete. Coaching cues: Emphasize leading with the

knee, squaring up hips and shoulders to the hurdles, and letting the body balance itself without the use of the arms. It is a great drill to teach body awareness and balance to eliminate rotational problems. The arm drills are typically done in flats.

One Step Hurdles. From a standing start on the start line, hurdle any number of hurdles spaced so that the hurdler has only 1 step between hurdles. The 1st hurdle can be on the mark and others spaced at low heights for both men and women. The spacing will vary depending on the athlete and their talent/ ability level. The drill teaches athletes to lead with the knee, a flexed vigorous lead leg, and getting down very quickly with an active trail leg. It is also useful to eliminate “swinging” of the lead leg. The drill can be done in either spikes or flats at controlled higher speeds, with an emphasis on aggressive arm speed over the hurdle and projecting the hips through the hurdle. The one step hurdle drill, which can be done with any number of hurdles and done in shuttle fashion as well, was the most important drill in the Mary hurdle lineup.

Tempo Hurdles. Set(s) of any number of hurdles done in spikes with regular hurdle form with close to all out intensity. Example: 3 Hurdles x 2 x 2. Athletes should be given ample recovery between reps and sets to assure that the correct motor patterns are trained. A good rule of thumb is 3-3 ½ minutes per rep and 4-4 ½ minutes per set, longer for men depending on height of hurdles and the number of hurdles. We typically didn’t use more than 5-6 hurdles in this drill due to the fatigue factor. Often only 3-4 hurdles were used. The first hurdle is on the standard mark with the following discounted hurdles of 7.5-7.7m for women and 8.53m (28 feet) for men. Spacing can be modified to assure that the athlete is simulating the desired competition stride frequency. Hurdle heights can vary (we even alternated heights), but are typically lower, especially for men. Heights can also vary between sets. Tempo hurdles can be done with any type of start the coach chooses. Tempo hurdles were done as a preliminary drill prior to actual speed hurdling from blocks. Many coaches refer to this drill as rhythm hurdles.

400 Meter Tempo Hurdles. Sets of reps over any number of hurdles spaced from 15-25 meters apart and at race speed. Spacing can be whatever the athlete/coach determines, but we very seldom used standard spacing. The key is to change the spacing frequently between reps to force adjustments

and optical steering. Low recovery amounts should be the norm in this drill, mimicking the fatigue that an athlete will experience on race day. Lower hurdle heights can also be used, and the drill is best served in spikes.

Shuttle Hurdles. The athlete hurdles one lane of barriers in one direction and turns around and returns in another lane of hurdles, doing a series of loops/reps. The hurdles can be set at any height, although lower heights would typically be used as less energy and force is required for the lower heights in a drill that can be very demanding. The drill should be done in spikes with sets of different recovery times, depending on the objective. It is obviously a great drill for the intermediate hurdler in terms of teaching alternating legs, making adjustments (steering), and mimicking the demands of the 400 hurdle race in terms of fatigue/energy systems. It teaches the athlete to hurdle in a fatigued state, with the emphasis on speed endurance. The drill can also be done on the curves, making it much more demanding and challenging.

One Step Hurdles into Tempo 400 Hurdle Combo Drill. A 400 meter hurdle exercise that is typically done in spikes begins with the one step hurdle drill and goes right into tempo hurdles. The number of hurdles is dictated by the coach and depends on the goal of the drill. The drill usually covers 90-110 meters and can include any number of reps (circuits), and the amount of recovery again is based on the discretion of the coach and the desired conditioning level. The heights used in the drill can vary from 30-36 inches for men, while the women employ 30 inch barriers. The drill teaches the athlete to adjust, steer and maintain proper hurdle mechanics while fatigued. The drill can also be done in shuttle fashion, with the tempo hurdles being run up and back following the one steppers.

• Note: The weighted hand gloves discussed in the body of this article can be used in all the drills.

• Note: Our take on coaching cues, “Don’t overdo it. Keep it simple and to a minimum. Sometimes less talking can be much more effective than overloading the athlete with too much verbiage. Empower the athlete. Be positive and point out the good as well as the corrections that are needed. We often tell coaches more listening and less talking can be very helpful.”

It is very apparent from this presentation that there are a multitude of ways for the hurdle coach to solve the innumerable problems

they will encounter. Often a very “simple fix” can solve a big problem. Most fixes, however, will not occur without the joint effort and open communication between the coach and athlete. There must be a collaboration between the athlete and the coach, and the challenges must be shared. That was certainly the consensus of the athletes who responded to our survey. Jim Vahrenkamp, the successful head coach from the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, ND, summarized this very distinctly in his survey response, “There are athletes that are partners,” said the coach. “ They seek context and understanding and work to apply this knowledge to practice and competition. There are also athletes that don’t want any responsibility. Knowledge requires responsibility. Once you know you have the knowledge, the athlete is responsible for the application of this knowledge. Partners are awesome to work with. Especially ones that challenge or stretch what we as coaches and teachers know. The harmonious relationship between an expert athlete and coach is what produces some incredible things. Especially if the coach is one who is willing to challenge themselves to be better. “ That was very well put by Coach Vahrenkamp.

There were a number of themes that surfaced in this presentation, but the true thesis that emerged was this: It is only through a combination of trial and error, experimentation, simplification, customizing, employing the science of hurdling, and partnering with the athlete, that the coach will be able to guide the hurdler to the needed corrections to optimize performance.

1. Gambetta, Vern, Following the Functional Path, Clinics

2. Lindemann, Ralph, US Air Force Academy, Clinics, Articles

3. Mann, Ralph, The Mechanics of Sprinting and Hurdling, 2018 Edition

4. McFarlane, Brent, The Science of Hurdling and Speed, 4th Edition, Canadian Track & Field Association, 2000

5. Winckler, Gary, University of Illinois, Clinics, Conversations, Articles

Note: A special thanks to Ann Thorson and Amelia Sherman for editing and technical assistance

With decades of experience working with top-ranked programs across the country, TenCate brings the latest in surfacing, design and construction technology to the track market.

LSU Athletics Track and Field

Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA

tencategrass.us

Building healthier, more beautiful communities.

A coach’s effectiveness is contingent upon their ability to integrate a range of competencies: imparting technical, tactical and physical knowledge (professional knowledge); engaging in self-reflection and self-awareness for continuous personal growth (intrapersonal knowledge); and cultivating meaningful relationships with athletes (interpersonal knowledge (Jowett, 2007; Cote & Gilbert, 2009; Gilbert & Cote, 2013; Infurna, 2023; Papich, Bloom, & Dohme, 2024). Among these, interpersonal knowledge is particularly pivotal, enabling coaches to build high-quality relationships with athletes across varying ages, skill levels and personalities (Cote & Gilbert, 2009; Infurna, 2022). The coach-athlete relationship itself is a dynamic social interaction, wherein each individual’s emotions (closeness), cognitions (commitment), and behaviors (complementarity) continuously shape and influence the other (Jowett, 2007). Given that athletes possess unique needs, goals and expectations, it is essential for coaches to recognize these individual differences and adapt their approach accordingly (Cote & Gilbert, 2009; Becker, 2013; Papich et al., 2024). Developing such relationships requires substantial time and effort, as each coach-athlete relationship is as complex and challenging to navigate as the individuals involved (Jowett & Shanmugam, 2016). According to Jowett and Shanmugam (2016), the quality of the interpersonal connection between coach and athlete is central to effective and successful coaching. This dynamic may be particularly critical in individual sports, such as track and field, where the primary coach has a profound and direct influence on an athlete’s overall sporting experience (Infurna, 2022, 2023).

A high-quality coach-athlete relationship, characterized by mutual trust, respect and appreciation, serves as a powerful catalyst for motivation, assurance and comfort for both parties (Jowett, 2007). Such relationships are linked to a range of positive outcomes for athletes, including enhanced motivation (Adie & Jowett, 2010; Riley & Smith, 2011), passion (Lafreniere et al., 2011), performance (Jowett & Cockerill, 2003; Infurna, 2023), communication (Rhind & Jowett, 2011), and psychological wellbeing (Felton & Jowett, 2013). Coaches play a crucial role in fostering these outcomes by creating psychologically safe environments where athletes feel empowered to take interpersonal risks, such as voicing concerns, asking questions and proposing new ideas (Edmondson, 2018). Recent research by Jowett et al. (2023) further highlights the positive relationship between openness, conflict management and psychological safety, emphasizing their impact on the quality of the coach-athlete relationship. In contrast, environments marked by silence and a lack of communication contribute to toxic cultures that undermine athlete well-being and performance. Therefore, establishing an atmosphere of psychological safety, where open, honest, and direct communication is encouraged, is essential for cultivating effective coach-athlete relationships (Edmondson, 2018; Infurna, 2023). High-performance sport is characterized by high expectations and a strong emphasis on performance outcomes (Preston et al., 2021). Some scholars have questioned whether the environment of high-perfor-

mance collegiate athletics is conducive to fostering meaningful coach-athlete relationships (Harwood & Johnston, 2016; Preston et al., 2021). However, in individual sports, where frequent one-on-one interactions between coaches and athletes are more common (Infurna, 2023), athletes may rely heavily on the closeness of these relationships for support in their athletic endeavors (Rhind et al., 2012). Kerr (2021) emphasized that, from a safe sport perspective, establishing close, trusting coach-athlete relationships is essential for both the development and well-being of athletes, as well as for achieving optimal performance outcomes.

Positive coach-athlete relationships are consistently linked to favorable psychological outcomes for athletes (Coussens, Stone, & Donachie, 2024). Although empirical research examining the connection between perceived support and coach-athlete relationships is still limited, preliminary findings suggest a significant relationship between the two (Coussens et al., 2024). Coaches often serve as important role models for high-performing athletes, contributing to enhanced selfconfidence through guidance, encouragement and support (Jowett, 2007; Rhind et al., 2012; Jowett & Shanmugam, 2016). By fostering a nurturing environment, coaches can build positive interpersonal relationships that further support the development of athlete confidence (Infurna, 2022). While the importance of quality coach-athlete relationships is well-established (Jowett & Shanmugam, 2016; Jowett et al., 2023), much of the existing research in this area has relied on quantitative methods

(Jowett, 2007), resulting in a limited understanding of how coaches can cultivate these relationships in high-performance individual sports, such as track and field (Infurna, 2023). Thus, the purpose of the present study is to provide a deeper understanding of how and why collegiate track and field coaches develop quality relationships with their highperformance athletes (ages 18–24) while prioritizing their athletes’ needs and well-being. Additionally, the unique combination of academic, social and athletic pressures experienced by this age group may influence how coaches approach relationship-building (Infurna, 2022). To guide this investigation, the study was structured around three research questions: (1.) What do coaches perceive as the importance of developing quality relationships with highperformance collegiate athletes? (2.) What strategies do track and field coaches employ to build these relationships? (3.) How do coaches perceive their role in managing athletes’ athletic, personal and emotional success (Papich et al., 2024)?

This study employed a qualitative design to examine collegiate track and field coaches’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors regarding the development of high-quality coachathlete relationships (Percy et al., 2015). Situated within a constructivist epistemological paradigm (Poucher et al., 2020), the research was underpinned by the assumption that knowledge is socially constructed through human interaction and engagement with the surrounding world (Crotty, 1998). Accordingly, semi-structured interviews (SSIs) served as the primary method for data generation, allowing for the co-construction of meaning through in-depth dialogue between the researcher and participants. This approach was chosen to explore the nuanced interpersonal strategies coaches employ to foster meaningful and effective relationships with their athletes.

Participants were selected using purposive, criterion-based sampling to ensure alignment with the study’s research questions and objectives (Sparkes & Smith, 2014). Eligibility criteria required that participants: (a.) possessed a minimum of 10 years of collegiate-level track and field coaching experience (across NCAA Divisions I,

TABLE 1. PARTICIPANT DEMOGRAPHICS

Pseudonym

Evan Male 17

Enzo Male 19

Joseph Male 26

Logan Male 34

Harrison Male 17

Dominic Male 23

Santino Male 16

Roman Male 20

Nick Male 26

II, and/or III); (b.) had coached at least one national champion and multiple AllAmerican throwers over an extended period; and (c.) were currently serving in a collegiate coaching role. These criteria were intentionally established to recruit coaches with deep experiential knowledge of coaching highperforming throwers. A total of nine coaches participated, all of whom met the aforementioned criteria and had extensive histories of coaching elite-level throwers in events including the shot put (indoor and outdoor), weight throw (35/25 lb), hammer, discus, and javelin. Detailed demographic and professional information for each participant is provided in Table 1.

Following institutional review board (IRB) approval, potential participants were contacted via email and provided with a formal recruitment packet. This packet included an overview of the study’s purpose, guiding research questions and the interview protocol. Coaches who expressed interest in participating were instructed to contact the lead researcher to schedule an interview. Prior to data collection, each participant reviewed and signed an informed consent form outlining their rights, including confidentiality, voluntary participation and the ability to withdraw from the study at any time. To preserve anonymity, pseudonyms were assigned to all participants.

Semi-structured interviews (SSIs) were employed to elicit rich, detailed narratives from participants regarding their experiences, philosophies and relational strategies in coaching throwers (Sparkes & Smith, 2013; Papich et al., 2024). The interview process was dialogic in nature, allowing for co-construction of knowledge between the researcher and the participants (Smith & Sparkes, 2016). Each interview was guided

Division III

Division II

Division I

Division I

Division III

Division II

Division II

Division III

Division III

by a flexible protocol consisting of 10 openended questions, designed to elicit both broad reflections and specific examples. Key areas of inquiry included: (a.) the perceived importance of building quality relationships with collegiate throwers; (b.) specific strategies used to develop and maintain these relationships; and (c.) the coach’s perceived role in supporting athletes’ athletic, emotional and personal development. Opening questions (e.g., “What initially sparked your interest in coaching collegiate throwers?”; “Are there aspects beyond technical training that you consider integral to your coaching role?”) were followed by targeted prompts (e.g., “What does connecting with an athlete mean to you?”; “What strategies do you use to foster those connections?”; “What challenges have you faced in building these relationships?”). Concluding questions encouraged reflection and completeness (e.g., “Is there anything we haven’t covered that you would like to share?”). Interviews ranged from 47 to 123 minutes (M = 77 minutes) and were both audio and video recorded. Verbatim transcription was performed by a professional third-party service.

A reflexive thematic analysis was conducted to generate, interpret, and report patterns within the data, consistent with the methodological guidelines of Braun and Clarke (2019). Rooted in a constructionist epistemology, the analysis was shaped by the researcher’s active role in interpreting participants’ accounts. Themes were not simply extracted but constructed through an iterative process of engagement, informed by both the data and the researcher’s experiential knowledge of the sport domain (Lincoln et al., 2018). The lead researcher’s background in coaching collegiate throwers served as an asset in building rapport and contextualizing participants’ responses, several of whom he had known professionally

prior to the study.

Each transcript (totaling 115 pages) was read in full a minimum of four times to ensure immersion in the data (Sparkes & Smith, 2014). Initial codes were developed inductively, grounded in participants’ language and meanings, and organized into broader themes through recursive engagement with the data. The author collaborated with two outside researchers who have extensive experience in conducting qualitative research studies. The two researchers assisted in the initial coding and development of the overarching themes of the study. Consistent with recommendations for evaluating qualitative rigor in sport and exercise psychology, the study adopted a flexible, criteria-based approach to trustworthiness, rather than adhering to predetermined, fixed benchmarks (Smith & McGannon, 2018; Sparkes & Smith, 2014). The themes presented in the findings are intended to contribute meaningfully to ongoing scholarly and applied conversations about cultivating close, trusting coach-athlete relationships in high performance sport (Papich et al., 2024).

Following the analysis, the author, with support from two outside researchers, generated two overarching themes: Coach-Athlete Closeness and Traversing Close CoachAthlete Relationships. The following section provides descriptions and quotes that describe these two themes. Pseudonyms are used throughout the section to protect participants’ identities.

COACH–ATHLETE CLOSENESS DEVELOPING CONNECTIONS WITH EACH THROWER

This theme explores the establishment of a shared bond and connection between the coach and athlete. Coaches believed the connection developed with each thrower was fundamental for building a strong rela-

tionship with them. All nine coaches emphasized that strong coach–athlete connections were foundational to high performance in throwing events. Coaches described these connections as evolving from mutual respect, daily dialogue and consistent attention to each athlete’s holistic development. Because throws training often happens in small-group or one-onone formats, coaches and athletes spend substantial unsupervised time together, which both facilitates connection and requires ethical vigilance, such as Joseph’s response, “You can’t separate the athlete from the person. If they’re dealing with something outside of track, it shows up in the ring. My job is to notice that and respond accordingly. Sometimes it means taking the thrower aside during warmups and checking in on them. I can usually tell is something is off, which then can lead to a poor practice. The more time I spending learning about each of my throwers the more I can assist them with things outside of track.”

Similarly, Evan shared, “I make it a point to get around to each thrower during their general warmup. This gives me time to check in and see how things are going.”

Santino shared, “Making connections is really important early on in the season. Our athletes come to us with baggage sometimes. It is our job to try to get them to forget about life for the couple of hours they are at practice. Getting to know them early on in the season helps when things get difficult later on.”

This connection is further nurtured by oneon-one time between the coach and their throwers. For example, through preseason training sessions, Roman shared, “I get to know my athletes a lot during our preseason training sessions. This is where I believe our bonds begin to form. Preseason training isn’t just about getting into shape before the official start of the season. It is a way for us as event group coaches to really get to know our athletes. This is where trust is formed. I sometimes spend more time with my freshmen and sophomore throwers because I want to build a strong relationship with them. By this point, I really trust that my juniors and seniors are doing what they are supposed to be doing. Sometimes the younger athletes need more during these sessions than a nice job for completing the workout.”

Although these coaches believed in the importance of getting to know their throwers on a more personal level, Logan and Harrison discussed the difficulties of managing coachathlete relationships.

“Earning the trust of your throwers can be difficult at times. I’ve had athletes ask me why we are doing a certain workout and question things because of something they saw on social media. I make it a point to share my philosophy with my throwers early on, especially during the recruiting process so they get to know me more,” shared Logan. Harrison, when discussing trust and respect, shared, “I’ve spent my entire coaching career working with Division III athletes. Just because you’ve coached athletes to earning All-American awards or national championships doesn’t mean that new throwers are going to buy-in immediately. It takes time to get to know your athletes. Getting to know them on a personal level helps because it shows them (the athlete) that you care about them as individuals and not just another thrower who can throw a hammer really far.

The connections between coaches and their athletes involved getting to know the athletes on a more personal level. And although the connection appears to be an important ingredient in the coach-athlete relationship dynamic, some coaches emphasized how difficult it can be to develop and establish a trusting relationship with their athletes. Nick shared, “I schedule individual meetings two times a semester with my throwers. I’m not full-time and can only be at practice a couple of times a week, so I make it a point to spend time with each thrower oneon-one to get to know them better.”

This theme explores coaches’ perceived importance of maintaining a close relationship with each thrower characterized by mutual care and respect. Due to the nature of the sport, throwing can be considered an individual sport with one-on-one time spent between coach and athlete, and in this case thrower. Coaches described how understanding each athlete’s “story” (background, motivation, personality, and support system) helped guide technical instruction and emotional support. Coaches often framed themselves as mentors and advocates in addition to technicians.

The closeness of the relationship had a major impact on the athletes’ throwing and overall wellbeing, as noted by Enzo, “I want to make sure as a coach that I get to know my athletes in the circle and how things outside of the circle might affect their throwing. I don’t think you can be a good throwing coach and not have some type of interpersonal relationship skills necessary to get to

know your throwers from a holistic perspective. I’ve coached some great national champions, and we would spend countless hours together after the season was over preparing for senior nationals and the possibilities of qualifying for the under 23 national team. If I can’t develop a positive working relationship with my thrower outside of just the throwing world. I would be doing them a disservice.”

The coach-athlete relationship had a major influence on the athletes’ personal and athletic success, as noted in these two quotes:

“They aren’t just throwers to me. They are an extension of my family at home. When their parents send them off to college, I want to make sure they have the best experience possible in track, academics, and life in general. I feel that most days are spent discussing things that have nothing to do with track, and that is ok. I want my kids to know that I care about them and that they can come to me with anything. Yes, coaching national champions is a wonderful experience, but making sure they graduate on-time is a more rewarding experience,” Dominic said.

“Creating a relationship with our athletes is so critical today. I feel at times that I’m the only person they can talk to about things outside of just throwing. I engage with each thrower every practice and ask them how their day is going and if there is anything I can do to help them with whatever is going on in their life. I give my cellphone number to all my throwers. They know they can reach out anytime. That helps build trust between the coach and thrower,” Harrison said.

Several coaches shared stories in which closeness helped athletes navigate academic stress, mental health challenges, or personal adversity, resulting in not only performance resilience but also long-term athlete wellbeing.

Joseph shared, “One of my throwers lost a family member right before coming back from break. Attending the service made a big impact on his life. It showed him that I really cared.”

Similarly, Evan shared, “I let my throwers know they can come to me with anything. And I mean anything. I know more about my throwers than their families or significant others probably do. They know they can tell me anything and that I’ll just listen.”

TRAVERSING CLOSE COACH-ATHLETE RELATIONSHIPS

This overarching theme describes how

coaches navigated close, trusting relationships with their throwers. Coaches emphasized their role as not only a coach, but rather a mentor and confidant in creating a psychologically safe environment for their throwers to flourish in. Coaches discussed performance well-being and the emotional well-being of their athletes.

All nine coaches emphasized their role in their approach of holistic coaching. Coaches discussed how shifts in athletes’ body language, tone or energy affected both their throwing performances and emotional wellbeing as athletes.

Santino shared, “When my All-American hammer thrower clams up, I know something is going on. I back off of the critique of the performance and focus on more encouraging thoughts. This usually means pulling them aside and checking up on them.”

Nick shared, “A lot of the time, it is the way they carry themselves before practice even begins. Or a competition for that matter. Body language plays a large role in the success of a thrower. You can’t win a meet in warmups, but you can win a meet at warmups,” he said with a chuckle. “Their body language tells the story. I can see it in their eyes. If they look excited, it means they are loose and relaxed. If they have a certain

look in their eyes matched with poor body language, it could be a recipe for disaster in competition.”

Similarly, Roman reflected on a moment where he confronted a thrower because he didn’t feel his “her head wasn’t into practice,” and it was interfering with her preparation with her training for nationals. He approached the athlete and said, “I know things are going pretty bad in your personal life right now. I understand that things outside of track happen. Only you know how you are feeling right now, and that is ok. I’m here to help you anyway I can. Only you can tell how much effort you are giving. If this is the best effort today, then I’m ok with it. If you’d like to take a pause for a couple of days, that is ok, too.”

By pausing the training session, having a one-on-one conversation with the thrower, Roman demonstrated empathy and understanding for his athlete. He was able demonstrate care for his athlete. He was honest with her, and gave her the autonomy to dictate whether she wanted to continue practicing that day. In addition, coaches encouraged athletes to be honest and provide feedback so that coaches could better respond to their needs.

This theme explores how coaches were

empathetic towards what their athletes were dealing with outside of track and field, including their personal relationships with friends, significant others and family members. Coaches recognized that throwers inevitably bring their emotions into the circle and believed they had an impactful role in helping them cope with these challenges. A commonality between five coaches was how much they appreciated the efforts of athletes’ holistic development on their throwing performance. For example, coaches were asked how they dealt with athletes when they came to practice looking “completely distraught.” All five coaches emphasized that they were always there for advice when needed.

Harrison shared, “I can tell when something is wrong. They come to practice without a certain energy they always have. Depending on the thrower, I know how much or how little I can probe when it comes with their personal lives.”

Similarly, Santino shared, “You get to know your kids over the course of a season and their careers. My kids feel comfortable sharing parts of their personal lives with me. I think that’s ok. It shows them that I care about them and am willing to help any way I can. I can usually tell if it’s a significant other distraction, course distraction, or friend thing. Depending on how practice is going,

I’ll pull them aside and ask if they need to leave and come back better the following day.”

Similarly, Enzo described that he would adjust the intensity or volume of the throwing session and his approach rather than directly drawing attention to the thrower or situation. “I can tell if my athletes’ minds aren’t in practice. You can tell a lot by the way they warm up and get ready to train. If I see they aren’t in it, I’ll back down the training session to meet their needs. They don’t know that I know they need it. You can just tell,” he said.

Also, Evan shared, “I know when they are coming from a hard class or lab. Sometimes they’ve been talking about a class assignment for weeks. When they show up and things aren’t looking good, I change gears to ensure they have a quality practice rather than what I had originally planned for them.”

Logan emphasized that each athlete and relationship was different, and he would approach each athlete and situation differently based on his relationship with his athletes. “Each athlete and situation is dif-

ferent. I tell all my throwers at the beginning of the season that I am there to support them with what they need help with. Some athletes come to me for relationship advice, other athletes come to me to talk about classes, while some just want to talk about throwing. That is fine with me. It’s my job to ensure they have the best experience possible. If they want to spend 30 minutes talking about a class or professor they hate, that’s fine by me. I know that’s what they need at that time,” he said.

These quotes exemplify how coaches were empathetic towards athletes’ challenges with things outside of track and field. Coaches were able to effectively meet the needs of their athletes by taking into consideration other factors in their lives that may have been impacting their performances. The coaches were able to find ways to help athletes move through their emotions and redirect their focus back to throwing. Coaches used a range of strategies to help athletes move through their emotions in the circle, while providing a safe space for them to seek advice or talk through what was happening in their personal lives.

The purpose of this study was to understand why and how experienced track and field throwing coaches developed quality relationships with their collegiate athletes that prioritized athletes’ needs and well-being. The nine coaches believed that developing close relationships built on mutual trust, empathy and respect ensured that athletes felt safe in their care and were able to reach their athletic potential. Grounded in rich qualitative data, two overarching themes emerged: Coach–Athlete Closeness and Traversing Close Coach–Athlete Relationships. These themes resonate with existing literature on the multidimensional nature of coach-athlete relationships, particularly the foundational elements of closeness, commitment, and complementarity (Jowett & Cockerill, 2003), while also advancing context-specific insights relevant to high performing track and field throwing coaches.

Consistent with prior research suggesting that closeness is marked by mutual trust, respect, and emotional support (Jowett, 2007), the coaches in this study empha-

sized the importance of getting to know the athlete beyond their athletic identity. Closeness, as described by these coaches, was not merely a byproduct of shared time but a deliberate outcome of one-on-one interactions, emotional availability, and an authentic investment in the athlete’s holistic development. These findings affirm the critical role of emotional intelligence and interpersonal attunement in coaching (Chan & Mallett, 2011).

The data also reflected how the individualized nature of throws coaching — often occurring in small groups or individualized sessions — afforded more frequent and informal contact. This proximity cultivated a unique space where relational bonds could form organically, but also demanded ethical sensitivity and consistent boundaries. Coaches like Joseph and Santino highlighted the need to “see the whole athlete,” noting that emotional disruptions outside of sport often manifest in the ring. Such insight aligns with the tenets of holistic sport psychology, which argue for the integration of personal and athletic domains in coach education and practice (Fraser-Thomas et al., 2008). Notably, closeness extended beyond camaraderie to include mentorship. Coaches acted not only as technicians, but also as trusted adult figures who offered life guidance. This is particularly evident in the coaches’ reflections on trust development, a relational process that some described as uneven and context-dependent. While veteran athletes were often granted more autonomy, newer athletes required more intentional efforts to build relational trust — echoing literature suggesting that relationship depth evolves over time and through shared experiences (Felton & Jowett, 2013).