CHIP LORD

FOLDING BACK TIME, FORM, & FORMAT

DECEMBER 5, 2020 -

FEBRUARY 20, 2021

BY KRISTEN WAWRUCK

BY KRISTEN WAWRUCK

Walking into Chip Lord’s 2021 exhibition at Rena Bransten Gallery is a trip into a mediated past, with images of 1980s zipping by amid stacks of U-matic tapes. Aptly entitled “Folding Back Time, Form, and Format,” this recent project of repositioned archival video works also functions as a mini-retrospective of Lord’s solo practice from the decade of the 1980s and beyond. Picking up from where his former art and architecture collective, Ant Farm, left off, the works featured in the exhibition demonstrate Lord’s incisive critique of mass-media consumption and ad-laden landscapes. Featured works such as Not Top Gun (1987) or Media Hostages (1985, with Antoni Muntadas and Branda Miller) exemplify the era’s video vanguard, showcasing Lord’s appropriation of the televisual lexicon and skillful edits to subvert the dominant media discourse. Over the last four decades, these works have been lauded in innumerable volumes and shown in exhibitions on video art. The point of this project is not to exhibit them again. Rather, we are confronted with the material nature of immaterial art. We do not encounter Lord’s videos through usual spectatorship. Here they are rendered as archive, in sculptural form as “Video Box Sets.”

While we think of video art living on screens in perpetuity, in reality—Lord reminds us, most of its life is in boxes. As the exhibition title suggests, he is not preoccupied with returning to the original formats for how these works were once seen. Rather than filling the gallery with boxy CRT monitors for each single-channel video work to remain faithful to the historical manner of viewing, as a museum might do, Lord has instead fashioned new sculptures. Each video work is presented as a bundle of five tapes, comprised of original U-matic copies and, depending on the set, supplemental footage. Bound together in wooden cases, the Video Boxed Set sculptures are neat cubes—a video brick resplendent in vintage glory, complete with original clamshell casings and artist-marked labels. They perch on top of a shelf fashioned out of plywood, calling to mind minimalist sculpture or modernist design. A small flatscreen monitor affixed to the wall above, also framed in plywood, plays short excerpts of its companion work to reveal just enough before looping again.

The plywood constructions call to mind the crates and shelvesof museum and gallery stacks, basements and storage spaces. But instead of preserving the archive in isolate in anticipation of an installation, Lord’s archive becomes fertile ground for new, playful works that transform and comment on the inherent nature of time-based media. We are presented with the “aura” of an original work even as we see multiple copies at once. After all, as Boris Groys has argued, a copy is never just a copy, but a new original. Each has its own idiosyncrasies and imperfections, and each has its own space of circulation. Lord’s staging of these copies brings out the way that any given video is not a singular, officially-sanctioned artwork but a chain of media transfers. In the absence of a U-matic player hooked up to a CRT monitor, a copy mutates into another analogue form, or most likely, as with Lord’s presentation, digitally. The degrading effects of time, temperature, and environment also impact time-based media’s signal quality, with institutional preservation practices making video precious in a way that it never wanted to be. Martha Rosler noted decades ago that the “museumization” of video art tames its radicality, a problem further compounded by the increasing rarity of the equipment needed to see video in “the original.” Lord’s Video Boxed Set sculptures sidestep the siloing of video art by bringing it into a new aesthetic register and insisting on a new type of confrontation in the gallery.

These types of existential dilemmas are relevant to any artist working with technology, and they are among the concerns that Felicity D. Scott probes across Ant Farm’s practice with the extensive Living Archive 7: Ant Farm volume and exhibition. Their ethos (and that of their peers) as a counter-institution to mainstream broadcasting was more concerned with “circulation, exchange, and disposability” than marketability. The creation of these works echoes the film industry’s transformation itself from celluloid to digital, which was a distinction that would be irrelevant within just a few years. And the very nature of this transitional medium—one of rapidly changing formats (Betamax, VHS, U-matic, etc.)—are, by definition, unarchivable. As a result, so much of the work made during this era has been lost. These are

Cadillac Ranch, 1974 is a permanent installation by Ant Farm (Lord, Marquez, Michels), located on I-40 just west of Amarillo, TX

Cadillac Ranch, 1974 is a permanent installation by Ant Farm (Lord, Marquez, Michels), located on I-40 just west of Amarillo, TX

conditions that become even more salient for someone who lost vast amounts of work due to a fire, as Lord and his Ant Farm collaborators did in 1978. But as their work was always self-consciously preoccupied with the future—time capsules, timelines, “The House of the Century,” and many others—so is this new presentation of Lord’s career as a video artist. The Video Boxed Set sculptures are an affront to video’s precarity, and by moving them into gallery circulation and out of storage, their longevity is perhaps even more secure.

The logic in re-assembling these works reflects the ethos of how they were originally created. In using found footage of Reagan’s inaugural parade in 1981 but adding a discordant and unskilled trumpet into the sound mix on Get Ready to March (part of Selected Works, Vol. 1, 1981), Lord uses the malleability of media and playing with affect to satirize the major political shift. He takes on the persona of a talking head at a news desk in ABSCAM (Framed) (1981), while Not Top Gun (1987) borrows from investigative reporting clichés with a pseudo-journalistic pilgrimage to the sites of the original film’s production. Interrogating a big budget, government-sanctioned Hollywood film—and incorporating found US Navy recruitment videos—acts as a proxy for larger systemic questions around economics, imperialism, and indoctrination.

Similarly, by putting these objects onto a shelf, the inertness of old “new media” reveals a complex web of relations and structures beyond. In particular, we see the material truths of planned obsolescence and consumer technology lifecycles: that of non-repair, expected re-consumption, and eventual toxic waste, with minerals finding their way back to the earth. The gesture of placing obsolete media on a shelf illustrates Bruno Latour’s “blackboxing” notion: when things break down, they end up revealing much more about the systems beyond the object itself. Video art, returning to Rosler, has always had an ethos of systemic critique, by sitting in opposition to its “parent technology,” broadcast television, which Lord’s videos themselves took reliably keen aim at. In revisiting those videos through their material weight, the Boxed Set Sculptures add new layers to this dynamic. They act as affecting reminders of art’s production, and at the same time as a playful overture to potential collectors, since there are truly so few (aside from institutions) concerned with acquiring video and timebased art. By changing the nature of this work’s collectability, Lord

challenges the viewer (and the buyer) to reckon with the expenses of equipment, space, labor, and care necessary for their survival.

Lord’s project is a new form of the readymade, albeit skillfully edited and repackaged. In each display TV, an embedded DVD player is tucked away unseen, bound to break down someday. This inevitability, coupled with the work’s transmutation into another non-archival format, reads poignantly. The net effect of standing in a space with all of the trailers playing continuously and simultaneously mirrors our daily screen-filled lives—flattened out and cacophonous—even as the content brings us briefly back to the era of Reaganomics that Lord eviscerates. In order to see each complete video work, one can buy the set, or, of course, visit his open-access Vimeo account, as I did while writing this piece. Lord also gave me a DVD copy of the video collection that accompanied the 2004 Ant Farm retrospective at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive—and I did not tell him that I lacked a functional player.

1 Boris Groys, “Time-Based Art,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 59–60, no. Spring-Autumn (2011): 341.

2 Martha Rosler, “Video: Shedding the Utopian Moment [1985],” in Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art, ed. Doug Hall and Sally Jo Fifer (New York: Aperture, 1990), 33.

3 Felicity D. Scott, Ant Farm - Allegorical Timewarp: The Media Fallout of July 21, 1969, Living Archive 7 (Barcelona: Actar, 2007), 137–38.

4 Scott, 137.

5 Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka, “Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method,” Leonardo 45, no. 5 (October 1, 2012): 429, https://doi. org/10.1162/LEON_a_00438. 6 Bruno Latour, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1999) as quoted in Hertz and Parikka, 428.

7 Rosler, “Video: Shedding the Utopian Moment,” 31.

Cadillac Ranch under construction June19, 1974

Cadillac Ranch under construction June19, 1974

Cadillac Ranch has become a civic public space for Amarillo. In June, 2020 it was painted black and tagged, following George Floyd’s killing.

2020)

Photo by Crystal Michelle (Amarillo, Texas, June 6,

Photo by Crystal Michelle (Amarillo, Texas, June 6,

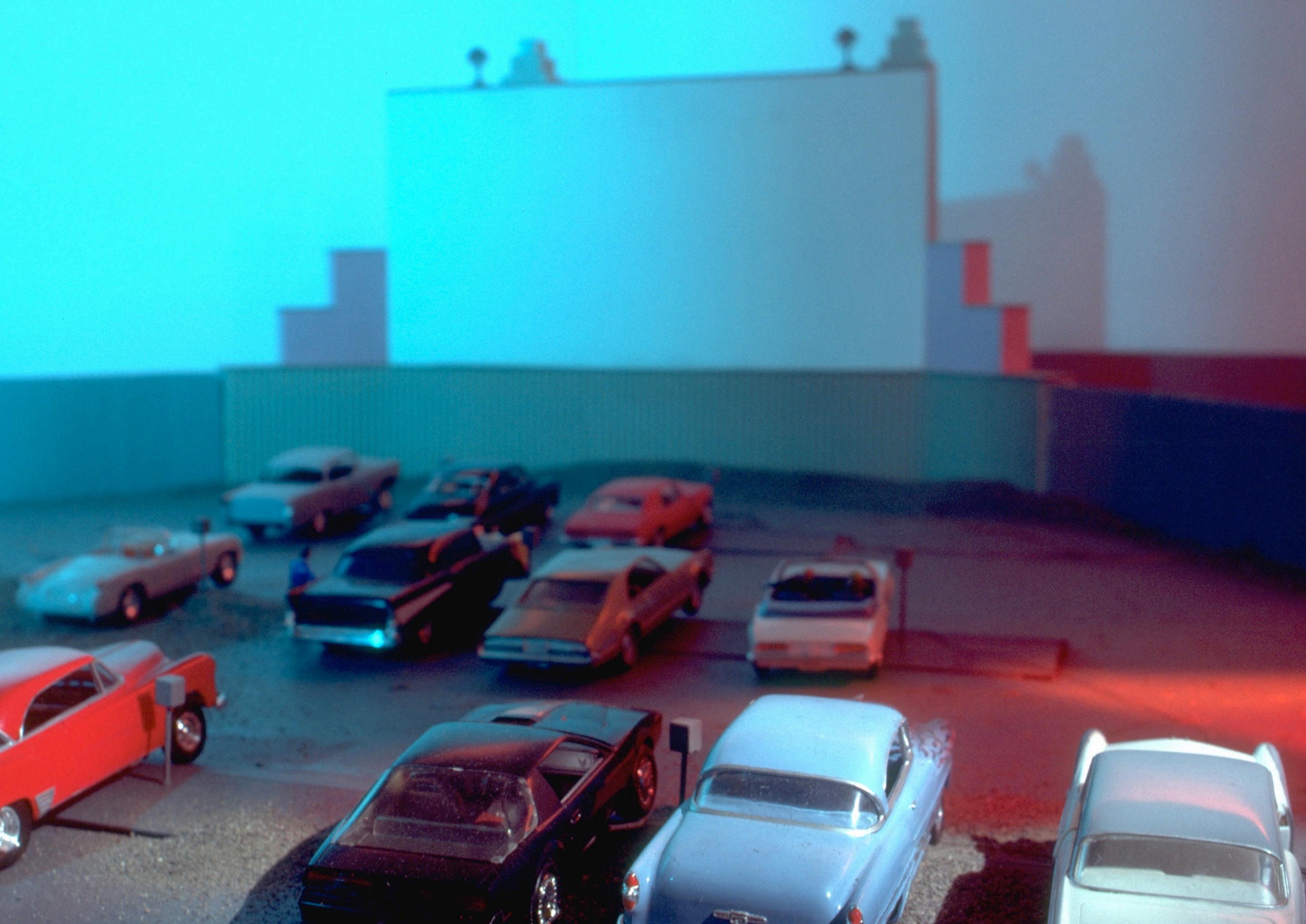

Though made 28 years later, the child’s dollhouse in American Utopia was the source for the original Picture Windows (Chip Lord + Mickey McGowan, 1990), a painted wooden structure that stands 7 feet tall and 8 feet wide, commissioned for the 1990 exhibit Bay Area Media at SFMOMA, curated by Bob Riley.The 2018 iteration has the addition of contemporary video – three digital channels reduced to fit on one widescreen LED TV/DVD player. Inside the “house” hand puppets and live actors perform routine daily activities which might be recognized as “utopian” American suburban life, activities observed from the distance of the street at twilight. In the final late-night scene, Hitchcock’s Rear Window plays on the TV.

The original 1990 piece is now in the collection of the Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie, Karlsruhe, Germany. American Utopia: Picture Windows Model, might be seen as housing the archive of the collaboration between Lord and Mickey McGowan. “The artists share an obsession with reconstructing and reframing the iconography of America for contemplation, analysis, and reconsideration,” wrote Curator Bob Riley in 1970.

In our current time, when the 1950’s as political and social model is still called out by the ex-President, when the country is divided between urban and rural, left and right, blue and red, this little house might be a symbol of a past utopian idea. One that “exists now only in the most priveleged suburbs, this two story, Cape Cod castle, with its perfect landscaping, perfect shutters, the perfect centered front door – a formal entrance that can never open.”

Installation view at ZKM Center for Art and Media

Installation view, Fresno Art Museum, 1990

Left + right: Chip Lord + Mickey McGowan, Picture Windows, 1990

Painted wood with 3 video monitors, 3 U-matic VCRs, synchronizer, app. 90 x 36 x 78 inches, TRT 17:15

Installation view at ZKM Center for Art and Media

Installation view, Fresno Art Museum, 1990

Left + right: Chip Lord + Mickey McGowan, Picture Windows, 1990

Painted wood with 3 video monitors, 3 U-matic VCRs, synchronizer, app. 90 x 36 x 78 inches, TRT 17:15

American Utopia, Picture Windows Model, 2018, child’s dollhouse on wooden plinth with three video windows, 24 x 18 x 12 inches

American Utopia, Picture Windows Model, 2018, child’s dollhouse on wooden plinth with three video windows, 24 x 18 x 12 inches

Video installations were an invented form in the 1970s, within a more generalized exploration by artists of the then new video medium. Single channel video works were difficult to market and exhibit in the gallery and museum world, but were embraced by curators who saw them as cutting-edge endeavors; video installations took up space and could be seen as sculptural works, and priced as unique or editioned objects.

While much contemporary video work has moved towards the spectacular, shown in large scale in darkened rooms with bench seating, the installation in Folding Back Time, Form, and Format scales down the work to an archival form, creating video sculptures in the process. Viewers are free to move around in the space as their attention shifts from one screen/object to the next, or as a sound catches their attention, creating their own unique auditory and visual re-mix.

Installation View, Folding Back Time, Form, and Format, Rena Bransten Gallery, 2020.

Works shown: American Utopia: Picture Windows Model (center); Motorist, NOT TOP GUN, + Media Hostages (on wall)

Video Box Set, 9 x 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches, including five U-matic tapes:

Easy Living, 1984 Edited Sub Master (BAVC)

EASY LIVING PAL Dub for Documenta

Easy Street, Episode 1: Unusual Weather

EASY LIVING/ AUTO FIRE LIFE, EL-8, uca 30

Easy Living Edited Master (BAVC label) + Framed DVD/Monitor, 18 ¾ x 23 x 3 ¾ inches, showing excerpts

Based on the original artwork: Chip Lord and Mickey McGowan

Easy Living, 1984

Single channel video, 19:20 min. with sound

The Cat Fund & WGBH, Boston, MA

On the set of Picture Windows, 1990, Chip Lord (left) + Mickey McGowan (right)

Still from Picture Windows, 1990, by Chip Lord + Mickey McGowan

On the set of Picture Windows, 1990, Chip Lord (left) + Mickey McGowan (right)

Still from Picture Windows, 1990, by Chip Lord + Mickey McGowan

On the set of Easy Living, 1983, Mickey McGowan at the beach at the Unknown Museum, Mill Valley, CA

On the set of Easy Living, 1983, Mickey McGowan at the beach at the Unknown Museum, Mill Valley, CA

Video Box Set, 9 x 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches, including five U-matic tapes:

Media Hostages, 1985, 26:00

Media Hostages, 1985, 26:00 MH - 18

Media Hostages, 1985, 26:00 MH -11

Media Hostages, 1985, 26:00 MH – 100

Media Hostages, 1985, 26:00 MH – 6 – Sub Master + Framed DVD/Monitor, 18 ¾ x 23 x 3 ¾ inches, showing excerpts

Based on the original artwork: Chip Lord, Branda Miller, Muntadas

Media Hostages, 1986

Single channel video, 28:00 min. with sound

Video Box Set, 9 x 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches, including five U-matic tapes:

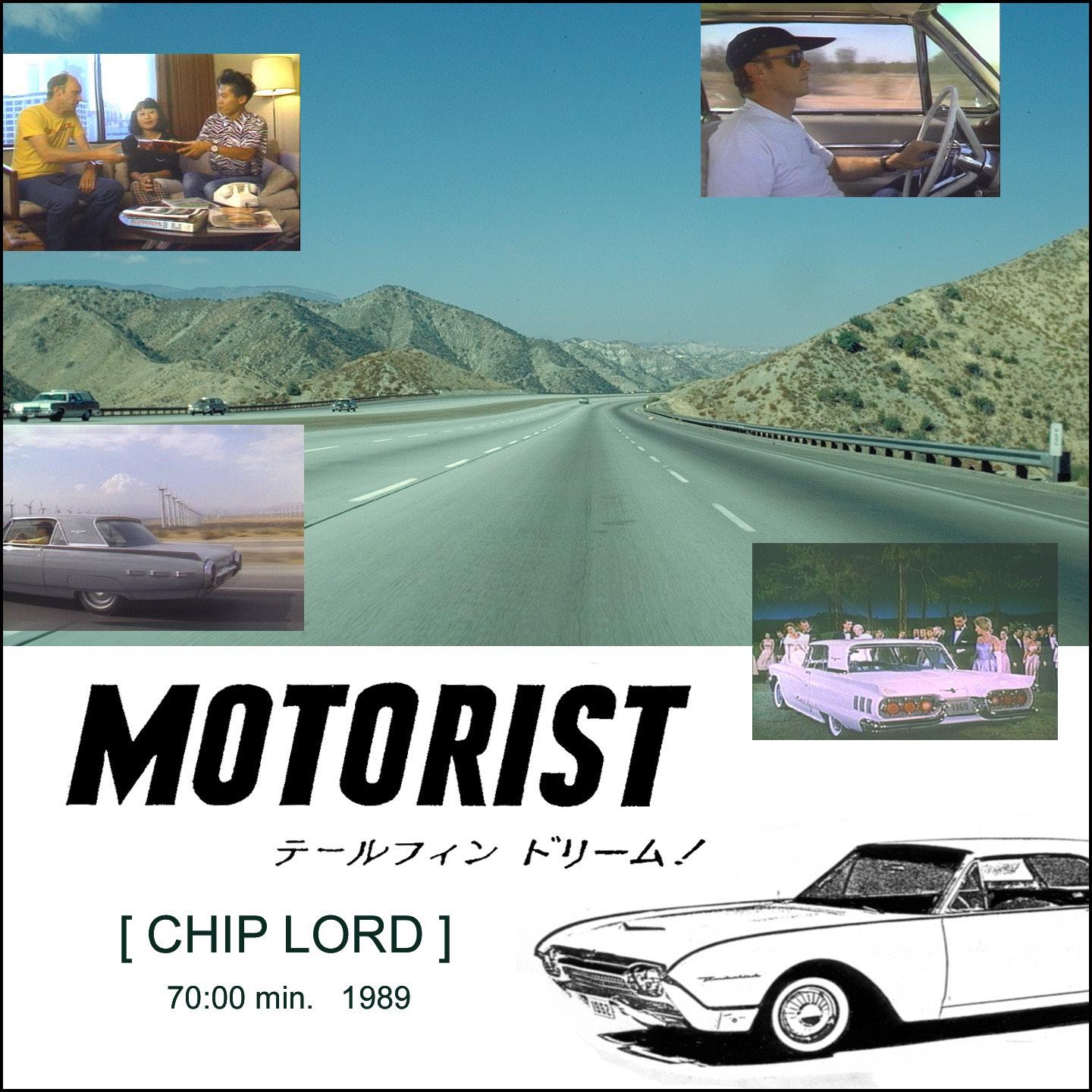

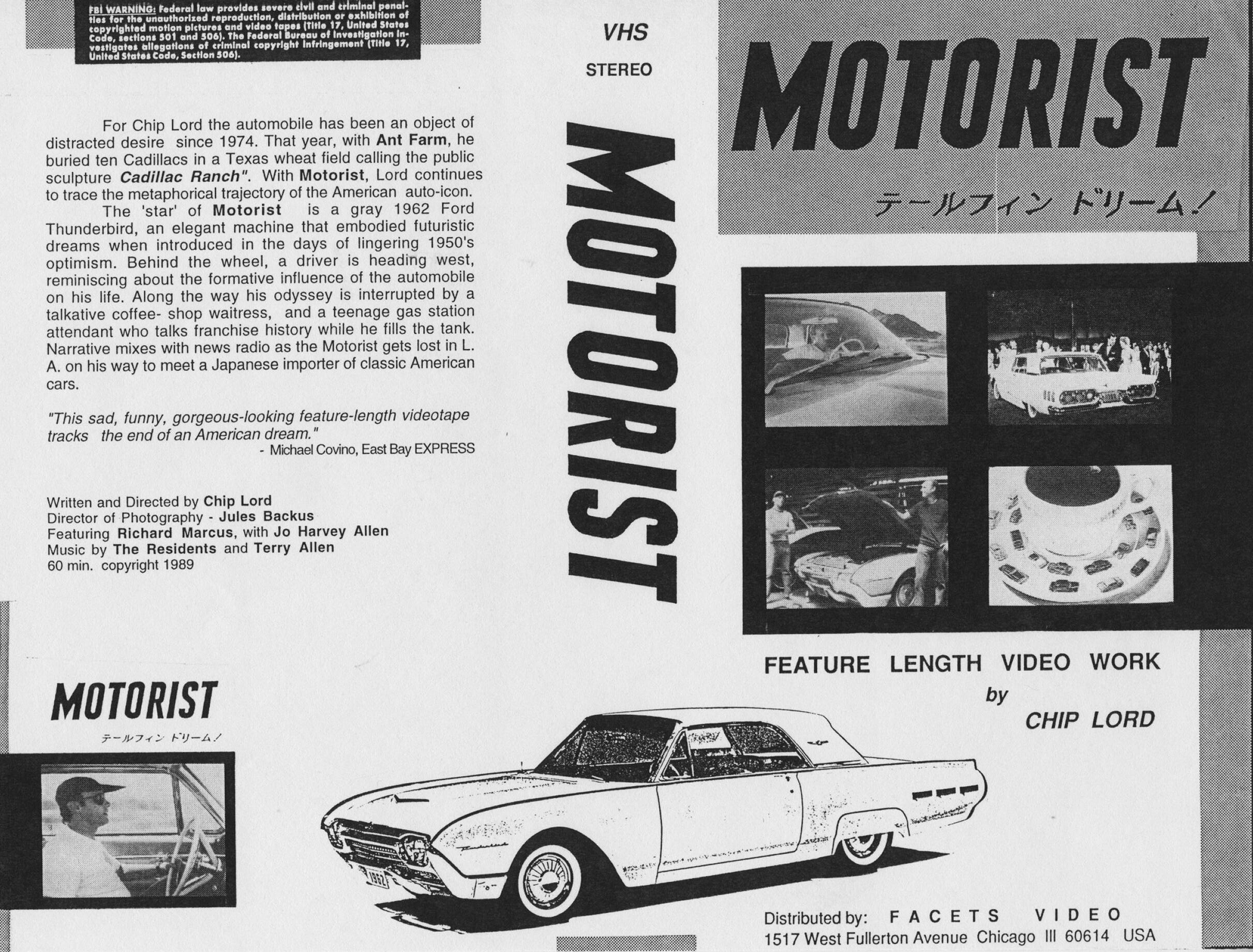

Motorist, 1989, 60:00 10.28.91

Motorist, 1989, 60:00 M-9

Motorist, 1989, 69:00 M-2

Motorist, 1989, 60:00 M-1 exhibition Dub

Motorist, 1989, 70:00 M-17 Dub from Beta SP master + Framed DVD/Monitor, 18 ¾ x 23 x 3 ¾ inches, showing excerpts

Based on the original artwork:

Chip Lord

MOTORIST, 1989

Single channel video, 70:00 min. with sound

Shown at: Whitney Biennial, 1989; London Film Festival, Berlin Film Festival, International Forum of New Cinema

Above: original DVD label for Motorist, 1989

On Location shooting Motorist, 1988 near Gila Bend Arizona (left to right: Chris Beaver, Chip Lord, Jules Backus, Richard Marcus). Photo by Jeanne C. Finley

Opposite page: original VHS label for Motorist, 1989

Above: original DVD label for Motorist, 1989

On Location shooting Motorist, 1988 near Gila Bend Arizona (left to right: Chris Beaver, Chip Lord, Jules Backus, Richard Marcus). Photo by Jeanne C. Finley

Opposite page: original VHS label for Motorist, 1989

Video Box Set, 9 x 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches, including five U-matic tapes:

CHIP LORD, Selected Works, 1977 – 1984

ID 1971 – 1981, CHIP LORD TOUR TAPE

1983 Compilation Reel, M-1

Easy Living & AUTO FIRE LIFE audition copy EL-7

YVR: Arrival/Departure, Edited Sub Master + Framed DVD/Monitor, 18 ¾ x 23 x 3 ¾ inches, showing excerpts

Based on the original artwork: Chip Lord

Selected Works, 1977 – 84

Single channel collection of seven titles, 28:00 min. with sound (Celebrity Author, Bi-Coastal, Executive Air Traveler, Get Ready to March, Three Drugs, AUTO FIRE LIFE)

Video Box Set, 9 x 4 3/4 x 6 1/2 inches, including five U-matic tapes:

NOT TOP GUN, 1986 Edit Master, 28:05 (no titles)

NOT TOP GUN Dubbing Master, BAVC, 3.24.88

NOT TOP GUN Paper Tiger TV CL 130

Training Manuevers, Master A, Modelmaking( (Protection sub Master)

Training Manuevers, Master B, Miramar

+ Framed DVD/Monitor, 18 ¾ x 23 x 3 ¾ inches, showing excerpts

Based on the original artwork:

Chip Lord

NOT TOP GUN, 1987

Single Channel video, 26:00 min.

Paper Tiger Television

Chip Lord grew up in 1950’s America, a time and place which has informed much of his work.Trained as an architect, he was a founding partner of Ant Farm, with whom he produced the video art classics “Media Burn” and “The Eternal Frame” as well as the public sculptures “Cadillac Ranch” in Amarillo TX, and the “House of the Century,” outside of Houston, TX.

Lord’s work crosses documentary and experimental boundaries and moves between video, photography and installation, often in collabortaion with other artists. An abiding interest in the complex culture of transportation systems has been the inspiration for numerous works, including the photo series “Executive Air Traveler” (1977 - 1980); “Airspaces” (2000 – 2011) and the public video installation “To & From LAX,” (2010 - 2015).

Chip Lord’s work has been exhibited and published widely and is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, The Tate Modern, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the FRAC Centre, the Pompidou Centre, and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. He is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Film & Digital Media, U.C. Santa Cruz, and has also taught in Architecture at CCA and Columbia University GSAPP. He lives in San Francisco.

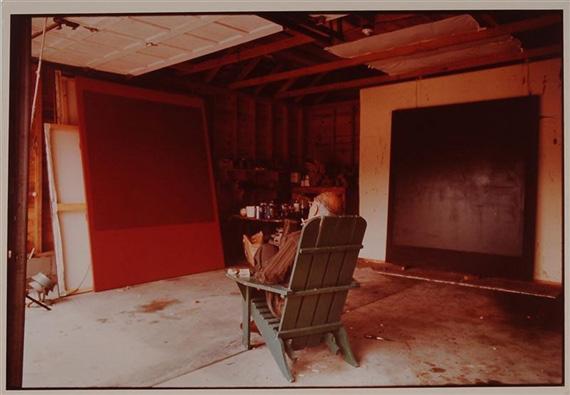

Chip Lord self-portrait that remakes the December 2010 Artforum ad for “IN THE TOWER: MARK ROTHKO”

Mark Rothko in his studio, Amagansett, NT, ca 1964

Photo credit: Hans Namuth © 1991 Hans Namath Estate/Center for Creative Photography

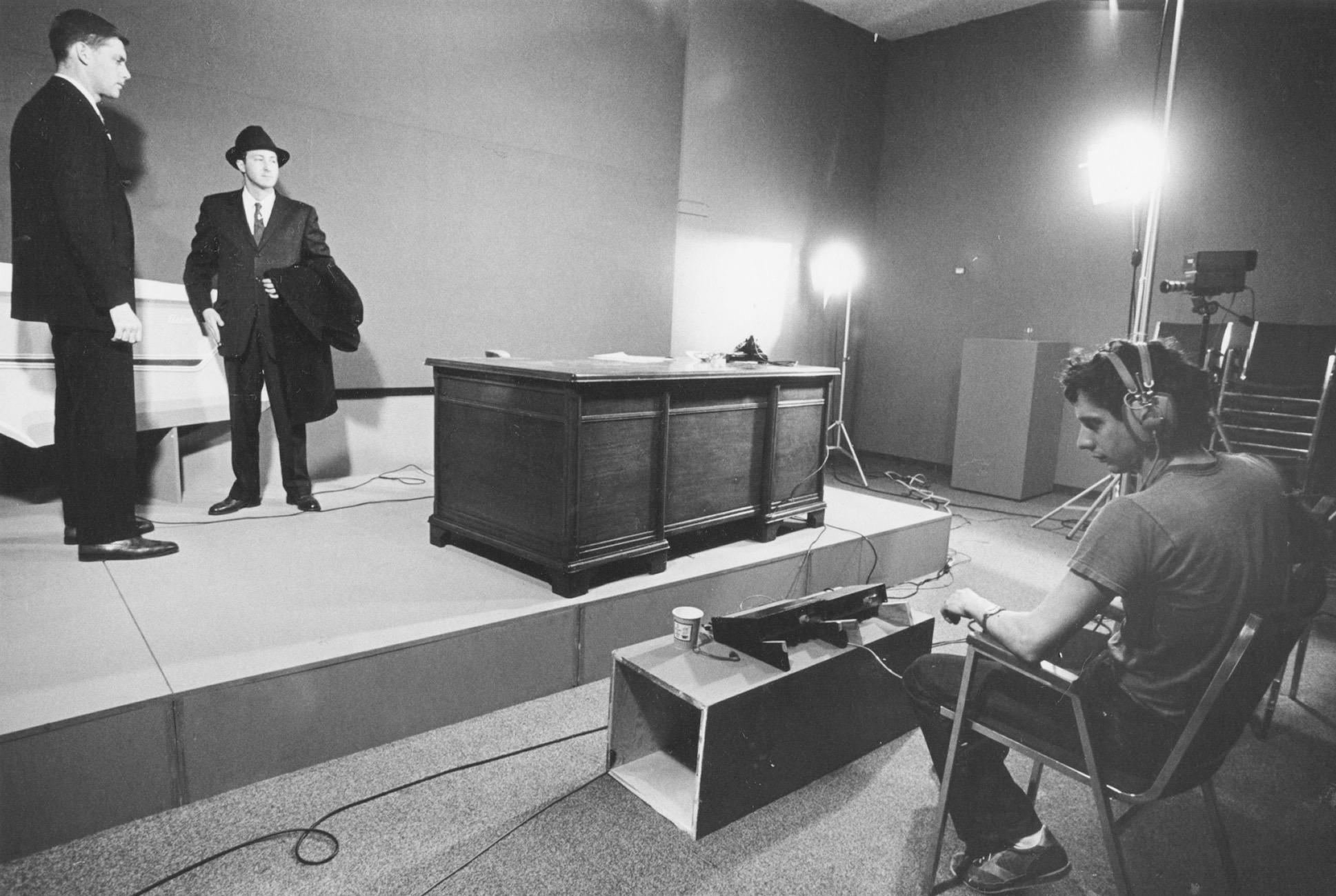

Production still, Chevrolet Training Film: The Remake, by Phil Garner and Chip Lord, 1978 – 1981, recorded to videotape at the Whitney Museum of Art, 1981

Production still, Chevrolet Training Film: The Remake, by Phil Garner and Chip Lord, 1978 – 1981, recorded to videotape at the Whitney Museum of Art, 1981