23 minute read

The perfect storm

When did current procurement practices fall out of favour, asks James Cash, and will clients and industry seize the opportunity to enact their transformation?

For shipwrecked mariners, the custom of the sea was the unwritt en convention that starving survivors in a lifeboat might draw lots to determine who survives and who – by feeding their shipmates – were to die. For centuries, this grisly custom was both recognised and accepted in broader society, with the surviving mariners tacitly pardoned. All of this changed in 1884 following the case of R v Dudley and Stephens (two of four survivors from the shipwrecked yacht Mignonett e who had killed and consumed a comatose shipmate), which found that necessity was no longer a defence of murder.

This change in public and legal opinion seems just as relevant today as the construction industry continues to experience its own perfect storm of revelations, not least in relation to the survivalist model of procurement that has predominated in recent decades.

Evidence that the procurement eco-system is distressed is compelling. Top-tier suppliers race to the bott om on price in order to win business to the detriment of those further down the supply chain, creating their own risks of insolvency. Profi ts and liquidity are consumed by over-competitive cost-cutt ing at every level as suppliers gnaw away at each other’s profi ts. And clients continue to incentivise these models of behaviour by overly relying on the cheapest option as an indicator of best value.

ILLUSTRATION: SIMON PEMBERTON

“Evidence that the procurement eco-system is distressed is compelling. Top-tier suppliers race to the bott om on price in order to win business to the detriment of those further down the supply chain. Profi ts and liquidity are consumed by over-competitive cost-cutt ing at every level as suppliers gnaw away at each other’s profi ts”

Procuring for value

The Construction Leadership Council’s Procuring for Value report urged clients to change their mindsets about value. With relatively small changes in approach and behaviour, they could reap signifi cant productivity gains across the construction sector. It urged the industry, clients and government to work together to establish a whole-life integrated sector to improve performance, end-user satisfaction and deliver broader societal benefi ts through higher-quality buildings.

Observing that the current approach is highly transactional, the report said there was litt le motivation for designers, contractors and suppliers to engage with each other at an early stage of a project or take an interest and learn from the building once it is in use. All parties were, therefore, destined to repeat mistakes. They fail to adopt best practice, the result of which is buildings that do not meet the needs and expectations of the people that live and work there.

Procurement systems, the report said, need to align the objectives of multiple project stakeholders to create the most signifi cant value. The UK government’s Industrial Strategy Whitepaper in 2017 introduced the balanced scorecard that requires procurers to consider relevant social and economic objectives, such as skills development, diverse supply chains and sustainability, as well as cost-eff ectiveness.

However, while the scorecard is a useful starting point for a new defi nition of value, many in the industry consider it is still too broad and open to interpretation. And currently it acts as a tick-box exercise to go through, rather than a project enhancing tool.

By developing an industry-wide defi nition of value that takes into

At its worst, this leads to poorer outcomes, including substandard and potentially unsafe buildings, unhappy tenants, and a fi nancially distressed and demoralised construction industry. It’s unsustainable and there are no long-term benefi ts for anyone.

So, have we fi nally reached a point where these visible and tangible defects in the procurement process have become unpalatable to the industry and society at large? Will a sea change in behaviour follow and what could that look like?

Richard Harral, Technical Director at CABE, says: “I think we’re at a tipping point where we have to make some very conscious decisions about whether to carry on as we have done for decades or start to invest in changing our approach to procurement and value.

“I’d argue very strongly that continuing to procure as we have done is unacceptable and ultimately not in the interest of anyone in the development chain. That includes clients, consultants, contractors and residents.”

Downward spiral

The procurement process is currently trapped in a vicious circle. Complexity and under-performance in the construction industry oft en push clients to fi xate on the lowest capital cost as the only indicator of value. However, lowest capital cost models of procurement create a system that suppresses costs in a way that distorts contractor and supplier business models.

Construction businesses respond by cutt ing costs to stay competitive, but not by improving productivity or effi ciency (as should happen in a genuinely competitive market). Instead they marginally chip away at quality. Poor outcomes follow; poor-quality assets that oft en involve higher maintenance costs over the life of the building. Dissatisfaction with the quality of

account more than the initial capital cost, the industry can produce a universal methodology for procurement and promote shared and consistent standards across the industry.

The industry also needs to work with the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) to develop cost and performance benchmarks for assets and suppliers. Creating an industry dashboard that is regularly updated will enable the industry to demonstrate it has increased capacity, productivity and reduced negative environmental impacts.

The report also recommended establishing an end-user rating system for built assets to help monitor how the people living and working in them view those assets. Meanwhile, developing a cross-industry prequalifi cation process would reduce bureaucracy from the procurement system.

the outcome reinforces the client’s view that if they Perceptions of value cannot guarantee the quality of the build, they should A critical factor in improving the procurement process pay as litt le as possible, which perpetuates under- involves redefi ning clients’ perception of what value is. pricing to win work. So the downward cycle continues. In July 2018, the government published

“The evidence is clear that this approach is not the Construction Sector Deal, and the report of working,” Harral says. “Tier one contracting is the Public Administration and Constitutional Aff airs increasingly unprofi table and unviable. Do we need Committ ee, which determined that the collapse any bett er evidence than the collapse of fi rms such of Carillion was due in part to the government’s as Carillion to recognise that cost suppression has procurement policies. In response, the Construction gone too far?” Leadership Council (CLC) published Procuring for

The signs are that the sector’s predominant Value, sett ing out recommendations for creating a business models are not just unsustainable but sustainable business model for the entire supply chain. potentially unsafe. There are also The author of the report, compelling indicators that it is damaging the people who work in the industry. According to a report by the “Continuing to procure as Ann Bentley, is a CLC member and global director at international cost management and quantity Chartered Institute of Building, 26% of construction industry professionals we have done surveyor Rider Levett Bucknall. She says there are several factors thought about taking their own lives in 2019. It’s a factor that can only have increased as a result of Covid-19 and is not in the interest of inhibiting clients from taking a value-led approach right now. Further research showed clients didn’t have the lockdown. Harral says: “The human cost of anyone in the common standards and there was also a lack of knowledge. bad procurement to the construction development “There were oft en tough time industry itself – in mental health and physical health terms – is both chain” and annual budget pressures. People didn’t want to be the fi rst to do it. And unsustainable and unjustifi able. The in some places, there was a conviction stress experienced by people working in an over- that lowest price gives the best value, even though the competitive market remains one of the key reasons evidence tells us that isn’t the case. for construction’s critical skills shortage. If clients “We came up with some solutions to this. Such want a more skilled, stable and competent workforce, as having a more common defi nition of what value they need to think actively about how their approach is, and enhancing the competence of practitioners, to procurement can support a bett er working particularly in advisors, so that they could talk about environment.” value. People need real evidence about value, as

Meanwhile, with an ever-increasing focus on opposed to rhetoric.” climate change, the construction sector needs to be This could include a consistent digital platform to more capable of designing and delivering buildings capture and analyse the information that is coming that perform as predicted. While legislation, such as the Building Safety Bill, aims to have a positive impact on the industry, it should also prompt client bodies to think diff erently about procurement activities and their development process.

“When you drive costs down in construction, it’s not like shopping online and gett ing price comparisons,” Harral notes. “Ultimately the product changes to refl ect the price that’s paid. Where you’re gett ing that lower price, someone is taking less time, taking less profi t and less margin. They are changing something or doing things diff erently. That’s fi ne if the innovation is sound, but it can also mean poorer quality, or safety or durability.”

What then are the solutions that will lead to a signifi cant change in procurement?

Harral says: “Firstly clients must move away from the lowest capital price as a primary metric of success, to an approach that focuses on ensuring that projects are reasonably costed and that the supply chain and all the way down can make a reasonable profi t.

“An unprofi table sector cannot deliver the safe and sustainable buildings we need; and it cannot improve to deliver genuine improvements in effi ciency and productivity that can lead to meaningful reductions in cost and programme, which will help meet housing supply targets.”

in. The Construction Innovation Hub now has funding to develop a suite of tools that will help defi ne the value profi le for a given project because value is a diff erent thing according to diff erent projects for diff erent clients. Bentley says these tools will guide clients through the individual delivery models and commercial strategies needed to ensure the delivery of what is genuinely best value.

“It will also provide a benchmark facility against which you can forecast and measure performance. And that’s forecasting performance through the design period, and then measuring performance during the occupation period. If that’s tied in with the commercial models, it would give you incentives for the whole of the supply chain that will help you to deliver value on your projects.”

Instead of just looking at fi nance, clients can consider a whole range of diff erent values that might come to play on a project. Clients can discern what is most important to them and identify where value accrues on a project to establish a value profi le that can be converted into a value index.

Bentley says: “Instead of just tendering on the basis of price, you can tender against this value index. Not only will you be looking at price, but other factors such as the competence of contractors and designers, and also the human value of the actual building they’re going to deliver. Clients will be able to compare suppliers on a properly benchmarked index and pick the ones that present the best value to them.

“Value can be defi ned. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. With the sort of target that we’re developing at the hub, it will give everybody tools to create a value baseline. And I think it will be a gamechanger in terms of how value can be delivered.”

Bett er collaboration will improve outcomes

Once clients are able to compare a wider range of outcomes, rather than reacting on basic capital cost, the argument for bett er forms of procurement become self-evident. Harral says: “Client bodies need

to understand that it is impossible to generate real effi ciency and productivity gains in projects where the tender price is less than the real cost of completing the work. If those gains are achieved, it is most likely at the expense of something more valuable in the medium- to long-term.

“And if the economic arguments on their own are insuffi cient then regulation and increased integration of ethical values at strategic level must also be used to compel necessary change.”

In addition to a more formalised value defi nition and benchmark system there are several other useful tools that can provide bett er certainty in the delivery of projects, while also ensuring realistic expectations are established about the progress of the project at an early stage. Harral says: “There needs to be a shift to the use of alliancing and collaborative forms of procurement to support integrated design and construction supply chains. There are many good examples of how this can be achieved, but uptake remains low.”

Alliancing

The use of alliancing and partnering in construction and infrastructure projects are not new and was a key element of the 1998 Egan Report, Rethinking Construction. The concept involves two or more organisations working together to improve performance through agreeing on mutual objectives, devising a way for resolving any disputes and “committ ing themselves to continuous improvement, measuring progress and sharing gains”.

The thinking behind partnering is to depart from a traditional construction approach, based on arm’s length commercial and contractual relationships and onerous contract terms. It involves active management of all aspects of the project, as opposed to reactive management of putt ing things right when issues arise and depend on personal commitment and trusting relationships. The collaborative relationship involves sharing the risks and resolving problems throughout the life of the project.

“Flexibility underpins the alliance model,” says Paul Walsh partner at Hill Dickinson, “which allows the contract and parties to adapt easily to the changes to address complex design, construction and environmental issues that may not be evident at the outset of the project. This is perhaps the key advantage of the alliance model.”

Clients and contractors expect change and innovation in delivery timescales with the focus on outcome as opposed to the process, which may aff ect

timings and budget. The alliance model works on a unifi ed agreement under which all parties share the benefi ts and risks. This is diff erent from the traditional contracting model where each party operates under its own separate contract containing separate objectives.

Walsh adds: “Any gain or pain is linked with good or poor performance overall and not to the performance of individual parties. The idea is to create an integrated structure whereby multiple suppliers work together under one central alliance to deliver the project as a whole.”

The collaborative framework has a set of shared values leading to unanimous and principle-based decision-making, ideally supported by several good-faith obligations such as co-operation and communication between the parties.

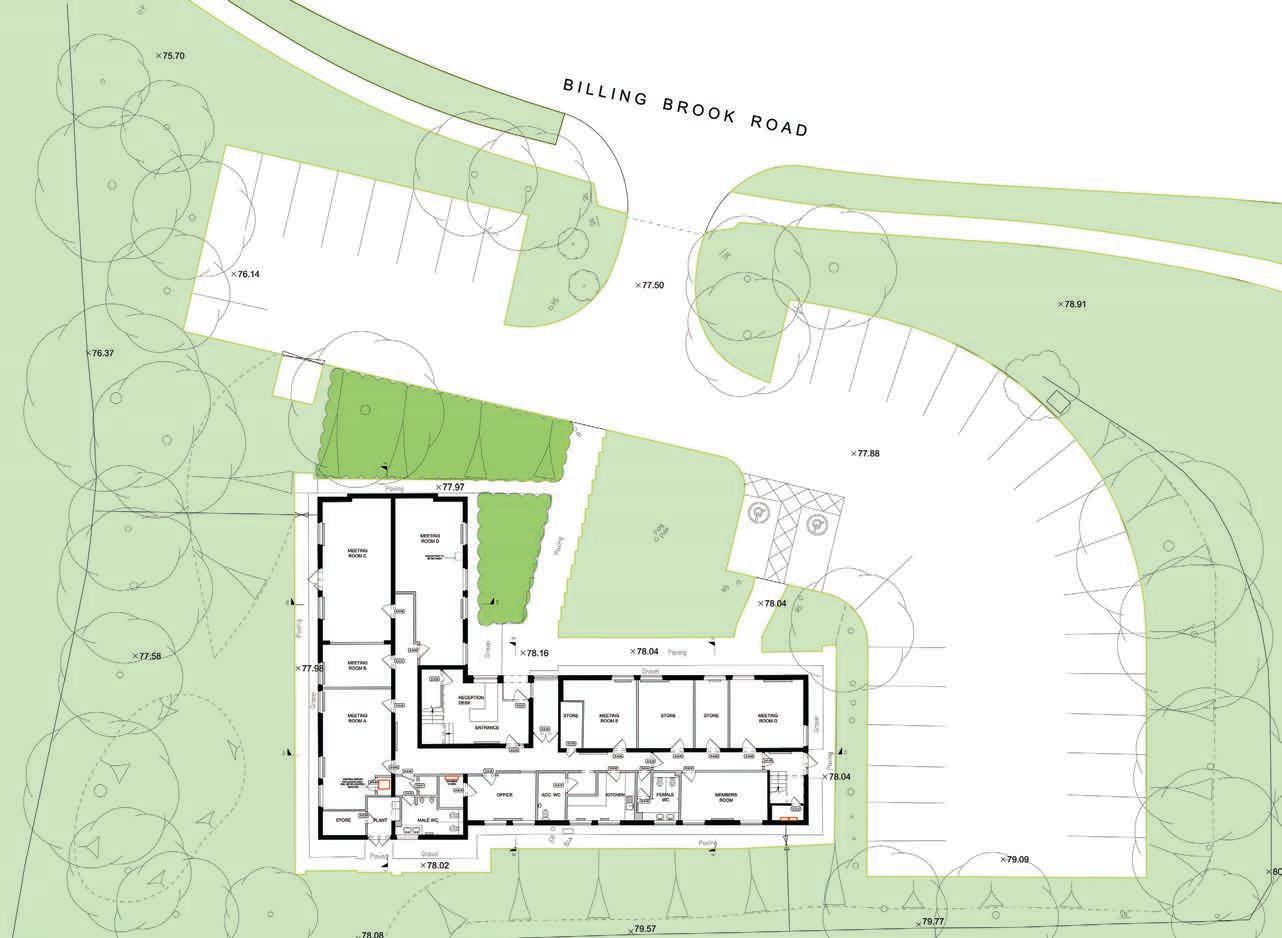

SHEFFIELD HALLAM UNIVERSITY CAMPUS MASTERPLAN

In June 2020, Sheffi eld Hallam University announced it had appointed three partner suppliers to form the Hallam Alliance to deliver the university’s new campus plan. The Alliance is described as a ground-breaking new construction industry procurement and delivery model, tipped to inspire change in the construction industry procurement. The Alliance comprises the university, design-consultancy BDP-Arup, construction fi rm BAM and facilities management specialists CBRE.

The university announced a 20-year development framework for the Sheffi eld Hallam estate and went out to tender to create an alliance who will be involved throughout the entire project. The alliance approach encourages a shared ethos of partnership, collaboration and innovation to bring about more eff ective and effi cient developments. The fi rst phase

Sheffi eld Hallam University went out to tender to create a ground-breaking new procurement and delivery model could see £220m invested over the next fi ve years focused on the university’s city centre estate.

The partnership will share profi ts and losses to ensure that all parties work effi ciently. The Hallam Alliance is one of the fi rst adopters of NEC4 Alliance Contract (ALC) operating under a governance structure with formal cooperative boards which require unanimous agreement, making decisions on issues on a best-for-project basis.

The contract is designed for use on major projects and programmes of work where longer-term collaborative ways of working are to be created. It can also be used to deliver a programme where several lower-value projects can be combined to create a major programme of works.

Paul Cleminson, Construction Director at BAM, which is behind ten current higher education buildings, says: “This new type of framework means the clients, designers, construction contractors and FM providers all have the same goals and objectives, with benefi ts such as a transparent, open-book costs approach and improved risk management. This builds mutual trust, which will then drive effi ciencies, standardisation and the continuous improvement we are all seeking.”

Integrated project insurance (IPI)

Similar to alliancing, IPI aims to align the interests of all parties with the functional needs of the client, helping to create a culture of collaboration. IPI collectively insures the client and all other alliance partners, including consultants, specialists, manufacturers, construction managers and their supply chains. It replaces the liability-driven professional indemnity insurance with fi nancial loss cover where the overrun costs exceed a specifi c level determined by the policy. IPI has been a long time in the development, fi rst conceived in Sir Michael Latham’s report in 1984, and reiterated in the Egan report in 1998 and subsequent eff orts to reduce the adversarial and fragmented nature of contracting arrangements. In 2008, Constructing Excellence told the government select committ ee on business and enterprise that too oft en insurance included: “redundant layers of consultant, contractor and supplier cover which oft en do not protect the client”. There is also a lot of waste. The committ ee heard as much as “£1bn was wasted every year on insurance cover that provides for the same types of risk”. Insurance brokers Griffi ths & Armour also calculated that for every £1 paid out in professional indemnity claims £5 had been spent in legal fees. Under a single policy, the need for litigation is signifi cantly reduced. IPI aims to improve and encourage integrated teams and remove the barriers to achieving integration. One of those barriers is the liability culture

and the insurances that are fragmented to mirror an older fragmented construction industry.

When you have many diff erent parties protected by many individual insurances, the policies don’t provide overall protection. Procurement sets people at each other’s throats from the beginning, and the separate insurances can accentuate the problem because they encourage the shift ing of blame onto the other players.

IPI is a single policy taken by the client and will cover the client and all the members of the team. It protects against the risks that were typically covered by contractors’ allrisks and third-party or public liability policies. It will also cover the risks usually covered by public indemnity policies but won’t cover it in quite the same way. It tends to cover the cost of the project – the cost plan – so that if there is a problem on the project and it causes the cost plan to overspend it will cover some of that, avoiding a lot of legal and forensic costs of pinning the blame.

There is a pain and gain share to the integrated team, and if all parties are working closely together it is in the interest of all members to ensure mistakes, defects and overruns do not arise.

It is also an opportunity for some contractors in the supply chain to be part of large projects where previously they could not accept the degree of liability that prime suppliers needed to pass down.

IPI, therefore, can have an impact that goes beyond the top-tier contractors. Helen Tapper, President of the Finishes & Interiors Sector (FIS) says: “I’m convinced that integrated project insurance will help accelerate genuine supply chain partnerships, real collaboration and a pipeline approach that will provide an opportunity to invest in off -site and the people we need.

“A move towards project insurance will start to ensure that risks are clearly thought through from the outset, throughout. And we move away from the build

Dudley College of Technology’s Advance II construction training centre embraced the collaborative IPI approach

and design culture that we fi nd ourselves in. A more project-based approach with risk management will reduce the risk in construction and enable companies to think beyond the next project.”

DUDLEY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY

Among recent projects that have successfully embraced the collaborative approach, Dudley College of Technology is an exemplar. IPI has been used twice by the college based in the West Midlands. The fi rst on its £12m Advance II construction training centre project designed by Metz Architects; and second on the £26m Institute of Transformational Technologies designed by Cullinan Studio currently under development.

The Advance II block was the fi rst offi cial government trial project for IPI. The aim was to shave 30% off the construction programme and deliver a capital cost saving of up to 20% by giving all parties ownership of the design decisions and contribute to decisions that balanced risk and resources.

In September 2014, Dudley College published the procurement notice, sett ing out expectations on IPI. Shortlisted bidders then took part in team-based behavioural workshops to assess which fi rms would be best capable of forming an alliance. In May 2015 the six key players – the client, the contractors Speller Metcalf and Metz Architects, Fulcro, H&H Architectural and Derry Building Services – signed an alliance contract binding each into a virtual company.

With a contingency fund of £1m, IPI gave the college a guaranteed cost of what their liability would be if the job went wrong. The project cost overrun liability is limited by a combination of pain/gain mechanism. In this instance, a cost overrun of up to £500,000 on

the agreed target build cost of £10m would be shared among the alliance, with overspend above £10.5m paid out through the insurance policy. Meanwhile, any savings up to 7.5% of the budget would be shared among the alliance members.

A paper published by Reading University based on an in-depth study of the project claimed: “Advance II, under IPI, has broken new ground in project procurement, organisation and delivery and demonstrated considerable benefi t from collaborative working among the key project participants. The project has achieved many notable successes and has generated valuable learning for future applications of IPI, as well as for collaborative project working more generally.

“The collaborative strength of the alliance has been tested by important developments on Advance II, notably during detailed design and construction when it emerged that the Target Outrun Cost might be exceeded and, later, when the agreed completion date came under threat. It is a testament to the robustness of the IPI model that both the Alliance Contract and IPI Policy remained unchallenged through the process; and also that the collaborative commitment among the Alliance prevailed and helped to identify solutions founded on the collective approach to risk and reward sharing.”

Two-stage book tendering

In two-stage tendering, the contractor is fi rst involved in increasing cost certainty and enhancing the construction process in an advisory capacity before the scheme is fully designed. Typically, the contractors will submit a price for assisting the client in designing the building, together with a schedule of rates – used to value the scope of works where the fi nal nature or quantities are not yet known – that in the second stage will be used to form a fi xed price for the complete works.

Jonathan Parker, national framework manager, Pagabo says: “Historically, the two-stage route has been the most popular within the construction industry, but in recent times the single-stage process has gained in popularity.

“The shift occurred because property teams are under increasing pressure to manage costs and need full visibility of these at the earliest stage. However, by doing this, they are losing the potential development fl exibility and added value that comes with the collaborative two-stage process.”

At the second stage, the pre-contract process is complete. The contractor enters into a detailed contract negotiation with the client, which will include price, programme and contract conditions. The client and their teams will collaborate with the chosen contractor to design and develop the whole project. At this stage, they create a bill of quantities, a fi nal price and fi nal contract with the contractor.

The advantages of this approach are that it brings in contractors/subcontractors in at an early stage of the project, helping them to deliver a more practical and buildable design, with fewer costly problems to resolve on-site during construction or to rectify aft er the build. Such early engagement tends to lead to improvements in the practicalities and aff ordability of the design, and construction methods reducing fi nancial and time costs.

Like the other initiatives discussed, two-stage tendering can lead to a more collaborative project team and help identify signifi cant risks early. Likewise, stakeholders can spot and share opportunities earlier in the process and develop them with more chance of success. Like IPI, this collaborative approach can lead to pain/gain-style agreements and the more successful the scheme is all parties benefi t.

However, two-stage tendering is oft en suited to projects that are more bespoke and complex where early contractor engagement is essential to assist in fi nalising a design and ensure effi ciencies on-site in terms of time and cost.

Time and tide

The industry needs to change now, particularly if it is to avoid similar pricing pressures, caused by the fi nancial crises as the economy recovers from Covid-19. Risks will only increase if a client’s choice of procurement pathway remains predicated on an assumption that lowest cost is best value. It’s time to recognise that in perusing lowest-cost models, clients are eff ectively driving the supply chain to feed on each other to remain solvent.

Procurers will need to put more time and resource into scoping out their projects, as Bentley says: “They should genuinely understand what things cost before they go out to tender. Many clients oft en don’t know what the costs are, they don’t know what is realistic, they just know what is cheapest.”

Meanwhile, contractors must look for more collaborative working that bridges the gaps between on-site, and off -site; design, build and facilities management. They must look for early-stage engagement to help their clients accurately price projects in a way that delivers sustainable benefi ts for all. Only then will procurement no longer feel like drawing straws in a lifeboat.