From Rhetoric to Reality:

The role of stories in designing the future

Monica Henderson

Student #10010101

MA Service Design

Royal College of Art

June 2022

Word Count: 9,770

Abstract

What role do stories play in our most successful innovations? Would innovation be successful without story? This critically reflective essay seeks to explore the hypothesis that stories have as much to do with the success of innovation as engineering.

The hypothesis will be tested through several qualitative methodologies:

• Case study1 analysis explores instances of design fiction2 and forms of prototyping3;

• Theoretical perspectives will be compared, contrasted and combined to better understand the role of stories as the catalyst for innovation;

• Self-narratives4 and autoethnographic5 references have been prepared for critical reflection

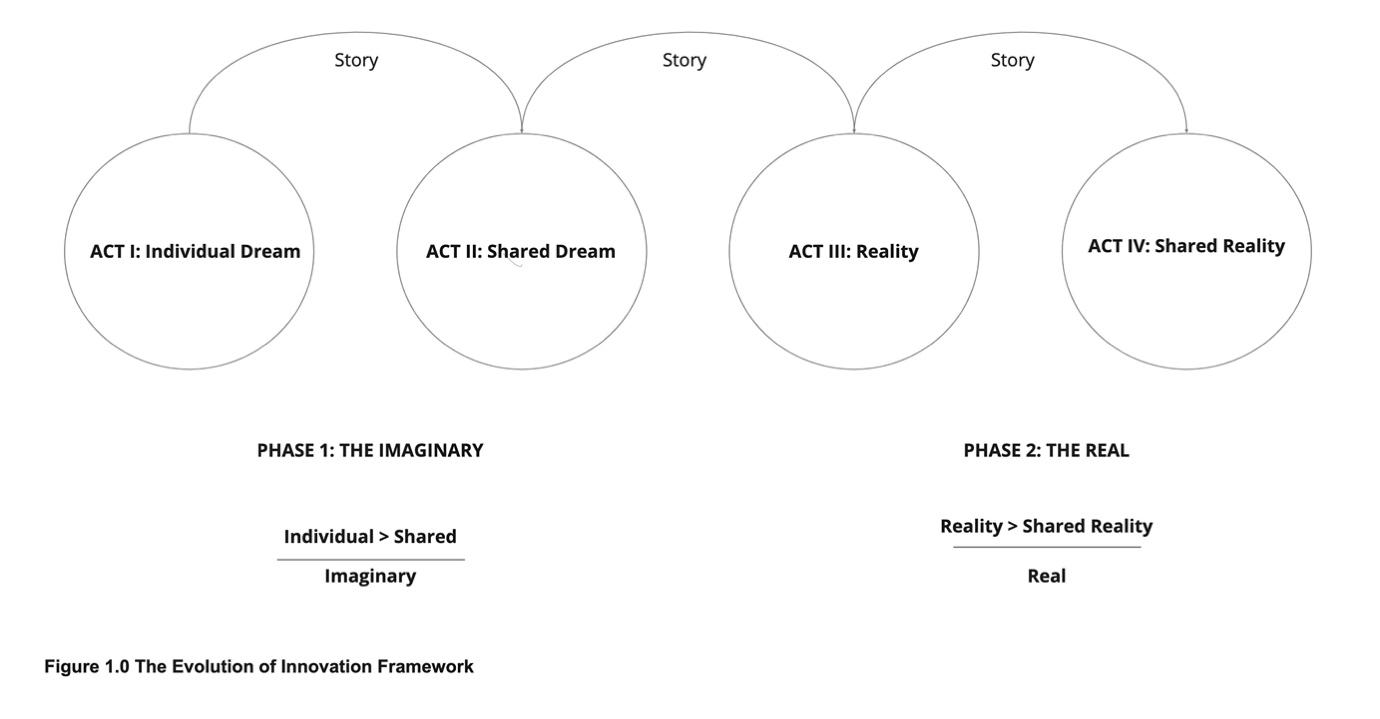

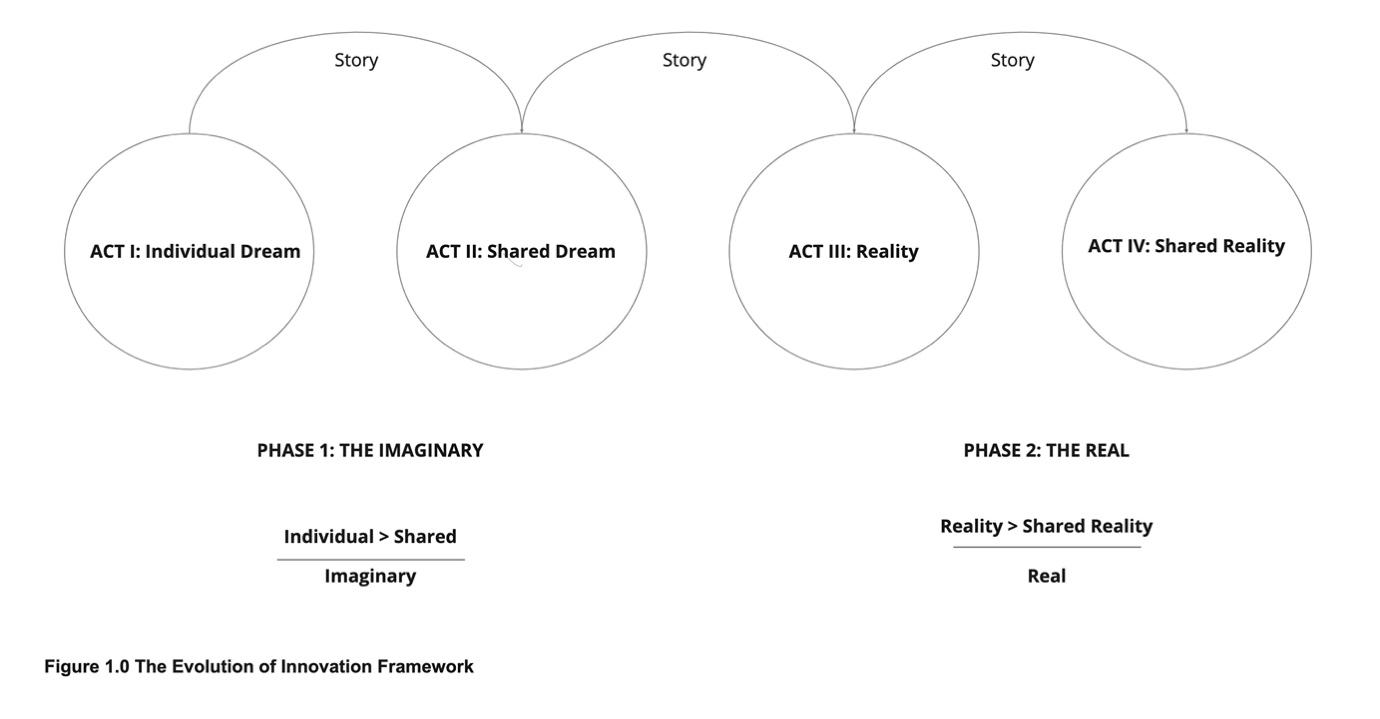

Against this backdrop, this essay explores the role of story in a proposed new Evolution of Innovation framework, presented in 2 parts. Part 1 explores the story through the ‘imaginary’ where future worlds are envisioned alongside ideated technological solutions. In Part 2, story is explored through the ‘real’ – where imaginary concepts are made a reality in the present day – with an eye for illustrating the process by which rhetoric becomes reality and the critical role that story plays in designing the future.

#Storytelling

#Individual_Dream

#Shared_dream

#Reality

#Shared_Reality

1 Gjoko Muratovski, Research for Designers: A Guide to Methods and Practice (London: Sage Publications, 2016), p. 49.

2 Bruce Hanington and Bella Martin, Universal Methods of Design Expanded and Revised (Beverly: Rockport Publishers, 2019), p. 82.

3 Hanington and Martin, p. 176.

4 Heewon Chang, Autoethnography as Method, Developing Qualitative Inquiry, v. 1 (Walnut Creek, Calif: Left Coast Press, 2008), p. 31.

5 Chang, p. 43.

1

2 Contents Page ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................................................. 3 PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 ANECDOTE: THE FUTURE IN THE PRESENT ..................................................................................................... 7 ACT I: THE “INDIVIDUAL DREAM” .................................................................................................................. 9 Story: The Critical 3rd Ingredient alongside Moore & Rogers 10 Speculative Design & Scenario Planning: “Scientific Dreaming” ................................................................ 11 Science Fiction & Technology: “Future Dreaming” 12 Case Study: Minority Report ...................................................................................................................... 13 ANECDOTE: MAC VS. PC 17 ACT II: THE “SHARED DREAM” ..................................................................................................................... 19 The Narrative Paradigm: Communication is Story .................................................................................... 19 Homo Narrans: Human Storytellers 19 The Stories we Tell Ourselves and Why they Matter .................................................................................. 21 Connecting the Dots: the “Shared Dream” 21 The Stories we are Told and Why they Matter ........................................................................................... 22 Case Study: 1984 23 ANECDOTE: SEEING IS BELIEVING ................................................................................................................ 26 ACT III: THE “REALITY” ................................................................................................................................. 28 Unicorns: Alive in the Modern Day 28 Design Fiction & Conceptual Design: Seeing is Believing 30 Pulling the Puzzle Together with Design Fiction & Concept Design 30 Case Study: Theranos ................................................................................................................................. 31 ANECDOTE: THE PITCH ................................................................................................................................ 35 INTRODUCTION: THE “SHARED REALITY” ..................................................................................................... 36 Storytelling: Lessons Learned through Prequels and Sequels 36 The Hero’s Quest: The Brand becomes the Hero ....................................................................................... 37 The Unwritten 4th Act – Loyalty 38 Case Study: ‘Get a Mac’ 39 CLOSING REFLECTIONS ................................................................................................................................ 41 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................................ 42

List of Illustrations

3

Figure 1.0 The Evolution of Innovation Framework

4

Preface

What role do stories play in our most successful innovations? Are we consciously aware of the influential role stories play at each phase in the evolution of innovation? How can we ensure stories are given as much care and attention as that given to engineering?

While most literature attributes technology advancements alone as the catalyst for innovation, especially in the 3rd Industrial Revolution, the role of story has not been recognised as having the same influence. The question that remains unanswered is: would innovation be successful without story? This critically reflective essay seeks to explore the hypothesis that stories have as much to do with the success of innovation as engineering.

The hypothesis will be tested through several qualitative methodologies. Case study6 analysis explores instances of design fiction7 and forms of prototyping8, in order to compare and contrast theoretical perspectives on the role of stories as the catalyst for innovation; storytelling is laced throughout providing anecdotal self-narratives9 and autoethnographic10 references. A concept map11 has also been created which provides a visual reference of a new proposed framework.

Against this backdrop, this essay explores the role of story in a proposed new Evolution of Innovation framework, presented in 2 parts. Part 1 explores the story through the ‘imaginary’ where future worlds are envisioned alongside technological solutions. In Part 2, story is explored through the ‘real’, where these imaginary concepts are made a reality in the present day.

6 Gjoko Muratovski, Research for Designers: A Guide to Methods and Practice (London: Sage Publications, 2016), p. 49.

7 Bruce Hanington and Bella Martin, Universal Methods of Design Expanded and Revised (Beverly: Rockport Publishers, 2019), p. 82.

8 Hanington and Martin, p. 176.

9 Heewon Chang, Autoethnography as Method, Developing Qualitative Inquiry, v. 1 (Walnut Creek, Calif: Left Coast Press, 2008), p. 31.

10 Chang, p. 43.

11 Hanington and Martin, p. 50.

5

Within this new Evolution of Innovation framework, this essay argues that 4 critical components of story, each dependent on the success of its predecessor, have as much to do with the diffusion of innovation, as innovation itself:

ACT I: The Individual Dream

ACT II: The Shared Dream

ACT III: Dreams to Reality

ACT IV: The Collective Reality/Shared Belief

This essay elucidates the process by which rhetoric becomes our reality and the critical role that story plays in designing the future.

6

Anecdote: The Future in the Present

It’s July 1st, 2002, Canada Day in Toronto, Ontario.

My college friends are now my flatmates. We are inseparable and spend every minute of our free time together As a part of our regular routine, we round out our weekend activities with a matinee.

Today is no different. Though, I’ll be meeting everyone at the theatre, I had some errands to run. Amazon doesn’t exist yet.

I plan to get to the movie theatre the way I always do; a 10-minute walk, followed by two trains. Uber doesn’t exist yet.

I’m lucky enough to have landed a job with a company that gave me a mobile phone. It’s the latest technology and it’s just the coolest thing ever. I no longer need to use the grimy public pay phone. I take out my Nokia 6610.

The iPhone doesn’t exist yet.

I text my flatmate, Karen, to see if everyone is still coming. She’s on point to coordinate with the 3 other girls at the house.

WhatsApp and iMessage don’t exist yet.

Texting is cool, I think, but it takes longer than making a phone call. I draft a cryptic message by pressing the physical alpha-numeric buttons,1-3 times each, and select the right characters.

Touch screens don’t exist yet.

I hope the message makes sense. I click send.

‘C U @ 2?’

I get a response 15 minutes later.

‘Y + 3 + MK!’

Fabulous, I think to myself. Everyone is coming, and Mairghead must be in town.

7

We had planned to see the latest blockbuster, Minority Report 12 It was all anyone could talk about. A science fiction movie starring Tom Cruise. The film is set in 2054, where John Anderton (Cruise) heads up the newly-established “Precrime” division. Murder rates had been skyrocketing and society turned to advances in technology to take a pre-emptive, rather than reactive, approach to preventing murders

In the opening scene, Anderton stands before a translucent glass computer monitor. Several images appear on the giant screen in rapid succession. Anderton uses his hand to interact with the images –“pinching”, “zooming” and, “swiping” Gestural controls don’t exist yet.

Cruise is able to access images of people, places, and things. These images, served up through different viewpoints, give him clues about crimes about to be committed. Instagram and YouTube don’t exist yet.

Cruise uses this mesmerising new technology in order to find clues, which help him locate, and ultimately apprehend, future criminals and, prevent murders from happening.

The ethics of the Precrime division – never more relevant than today – are discussed at length throughout the movie: what is destiny and what is free-will?

A line in the movie hits me, and echoes in my mind:

‘You don’t choose the things you believe in. They choose you.’13

12 Steven Spielberg, Minority Report (20th Century Studios, DreamWorks Pictures) <iTunes <https://itunes.apple.com/gb/movie/minority-report/id573718569> [accessed 28 May 2022].

13 Steven Spielberg, Minority Report - You Don’t Choose the Things You Believe In (20th Century Studios, DreamWorks Pictures, 2002) <YouTube, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AuGw8MSmjk>> [accessed 21 May 2022].

8

ACT I: The “Individual Dream”

This first section – the “Individual Dream” – makes the link between 2 well-known innovation theories (Moore’s Law, Diffusion of Innovation Theory), and 2 useful innovation methods (Speculative Design, Scenario Planning), and suggests that an explanation for the rapid pace of innovation must necessarily live in this convergence, and attempts to explain how these converged theories and corresponding methods, come to life in pop-culture-in the form of the modern science fiction narrative and diegetic prototype. Finally, it proposes that the first construct – the “individual dream” – is the important first ingredient in the innovation process

The autoethnographic “The Future in the Present” anecdote reminds us how far technological innovation has advanced in a mere two-decades ‘The 3rd Industrial Revolution, that began in the 1950s, is credited with the development of digital systems, communication, and rapid advances in computing power, which have enabled new ways of generating, processing, and sharing information.’14 While the impact of the 3rd Industrial revolution remains ever present in the maze of technology that now powers our daily lives, is technology alone responsible for innovation? Do we choose technology, or does it “choose us?” The answer as it turns out, is a bit of both.

Converging Theories: Moore’s Law and the Diffusion of Innovation Theory

Fast forward 2 decades, and the exponential advancements of technology have been nothing short of astounding. Now synonymous with disruption, technology seems to be limitless. Moore first predicted this exponential growth in 1965. His eponymous law, is a term used to refer to the observation that ‘the number of transistors in a densely integrated circuit (IC) doubles about every two years, while the cost of computing decreased by half ’15

14 Nicholas Davis, ‘World Economic Forum’, What Is the Fourth Industrial Revolution? 2016 <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/what-is-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/> [accessed 2 June 2022].

15 Gordon E. Moore, ‘Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits, Reprinted from Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965, Pp.114 Ff.’, IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter, 11.3 (2006), 33–35 <https://doi.org/10.1109/N-SSC.2006.4785860>.

9

While Moore’s Law positions technology alone as the single driving force of progress. But is Moore’s Law alone responsible for the innovation that defines our modern era, and its diffusion?

Everett Rogers had another idea. Rogers was an American communication theorist who explored the individual’s propensity for adopting new innovations. His now-famous Diffusion of Innovation Theory16 identifies five consumer segments in society: Innovators (2.5%), Early Adopters (13.5%), The Early Majority (34%), The Late Majority (34%), and Laggards (16%).

This categorisation and quantification prove insightful, especially when one considers that the percent allocation attributed to the laggard’s category (16%) is significantly larger than the innovator’s category (2.5%), which are on opposite ends of the spectrum. If latency in market adoption of innovation exists in concentrated amounts, one could argue that technological advancement alone cannot solely be responsible for innovation. Put another way technology alone is not the answer, and neither Moore, nor Everett’s theories explain the rapid pace of innovation in our modern era. So, what might?

Moore’s Law, and the Diffusion of Innovation Theory are surely interconnected. Moore’s Law speaks to exponential growth in technology capability, and Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory explains why not everyone in society readily adopts that technology. Technology needs a mechanism to instigate diffusion in society and facilitate its adoption. Perhaps this mechanism already exists in society. As storytelling.

Story: The Critical 3rd Ingredient alongside Moore & Rogers

In the pages that follow, this essay examines the critical role of stories, alongside Moores’ and Everett’s theories in driving innovations.

Storytelling is a tool used by innovators to help them communicate possible futures, enabled by technology, that we would not, and arguably could not, have otherwise been imagined. Innovators are often considered synonymous with futurists. A futurist is defined as ‘a way of thinking in the arts

16 Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed (New York: Free Press, 2003).

10

that started in the early 20th Century and tried to express, through a range of art forms, the characteristics, and images of the modern age, such as machines, speed, movement, and power.’

17 In other words, an individual who concentrates their thinking on future-based predictions involving the intersection between design and technology And their tool for prognostication? Speculative design.

Speculative design is a field of design focussed on the future world. According to Anthony Dunne & Fiona Raby, ‘This form of design thrives on imagination and aims to open-up new perspectives on what are sometimes called “wicked problems ” Speculative design creates space for discussion and debate about alternative ways of being, and it inspires and encourages people’s imaginations to flow freely.’18 Often associated with ‘abstract’ and ‘blue sky thinking,’ speculative design leverages several design methodologies to ground its foundation in believable circumstances. These circumstances are referred to as scenarios. Why are speculative designers, and speculative design more broadly, important when it comes to the diffusion of innovation? Because they foreshadow worlds that don’t yet exits.

Speculative Design & Scenario Planning: “Scientific Dreaming”

Scenario planning ‘often starts with what-if questions that are intended to open up spaces for debate and discussion. They are, therefore, by necessity provocative, intentionally simplified, and fictional.’

19 Scenario planning forecasts future states and explores possible, plausible, probable, and preferable circumstances. While it might be easy to dismiss scenario planning as abstract and inconsequential, it is, in fact, an important foundational element to future design because it gives innovators permission to consider what the future world could be/become Scenario planning informs innovation by designing the imaginary worlds of tomorrow, where the technology may exist first What do we get when we view futurism, speculative design, and scenario planning as a collective – placing the innovation in an imaginary future world? Science fiction And it has a critical role to play in the rapid technological advancements that characterise the 21st century.

17 ‘Futurist’, Cambridge Dictionary (Cambridge University Press 2022) <https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/futurist>.

18 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: The MIT Press, 2013), p. 2.

19 Dunne and Raby, p. 3.

11

Science fiction, or ‘Sci-Fi,’ or the scientist’s fevered dream, is a genre of storytelling that blends future scenarios with imagined innovative technology. ‘Hugo Gernsback, an American inventor and publisher was responsible for establishing Sci-Fi as a distinctive literary genre.’20 In 1929 he coined the term ‘scientification ’21 Later, in 1948, it was given further credence as a genre by John W. Campbell, who stated that “science fiction has the intriguing feature of causing its own forecasts to come true; because future scientists will have read the magazines seen the stories and recognized the validity of the science fiction engineering ” Could the modern science fiction narrative –powered by speculative design – and based on scientific facts have played an equal hand in inspiring innovation, alongside technology? It certainly seems plausible that science fiction has the ability to place the future in the minds of those in the present

Science Fiction & Technology: “Future Dreaming”

If the modern science fiction narrative is the birthplace of individual dreams about the future, and the role of technology in that future, the science fiction narrative, and cinematography in particularly then, are useful tools for analysing how an individual innovator’s dream becomes a shared dream. Why?

Because it inspires inventors and innovators alike to dream big about future worlds and the future technology needs those worlds dictate If we consider Minority Report22 and what were once considered far-fetched ideas, we bear witness to how elements of this future-forward technology became mainstream reality a mere decade or so later

Science fiction authors found their imaginative ideas in scientific evidence. In fact, ‘high-fidelity, polished, real-seeming representation of not-yet-possible or counterfactual propositions are a hallmark of the method. Some classic examples can be found in certain props or interactions from cinema, like the gestural interface in Minority Report.’23 The aforementioned “pinching”, “zooming” and “swiping” gestures didn’t exist when the movie premiered in 2002.

20 Thomas Michaud and Francesco Paolo Appio, ‘Envisioning Innovation Opportunities through Science Fiction’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 39.2 (2022), 121–31 (p. 122) <https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12613>.

21 James E. Gunn, The Road to Science-Fiction (Lanham (Md.) Oxford (GB): the Scarecrow press, 2002), p. 146.

22 Spielberg, Minority Report

23 Hanington and Martin, p. 82.

12

Interestingly, ‘Steven Spielberg assembled a team of scientists to create Minority Report.’24 With that team came plausibility – a sense of realism in a future world. One could argue that this level of authenticity elevates Science Fiction from entertainment to a form of speculative design The sci-fi stories are compelling, they resonate and, we yearn to believe that they will become our future reality. Simply put, it’s a plausible future scenario and we want the technology that that future offers.

Case Study: Minority Report

Film studios often employ futurists and scientists to educate their creative teams in a ‘Think Tank’ before a script is written. A Think Tank is a workshop that brings together scientific minds across industries to speculate on future world scenarios, and their corresponding dynamics. Think Tanks inspire the creative teams about possible futures which can then be written into the script

‘Futurist Peter Schwartz of Global Business Network (GBN) organised a two-day workshop for Minority Report’s director Steven Spielberg and his creative team. GBN convened a group of twentythree prominent experts from a wide variety of disciplines including physics (Neil Gershenfeld), urban planning (Peter Calthrope), architecture (William J. Mitchell), literature (Douglas Coupland), engineering (Harald Belker), and computer science (Jaron Lanier).’25 And the sessions of these great minds included overlapping industries and opposing schools of thought to help give a comprehensive and well-rounded perspective, which informed the design of speculative scenarios to write into the script. This is noteworthy because the futurist’s scientific schools of thought inspired the future world environment. But they didn’t do it alone. They had help.

Pushing the Boundaries: Dreaming Big

‘Boundary spanners’ are scientific experts, cast as full-time crew members, in Hollywood film productions. ‘A boundary spanner’s methodology involves their own consultation with appropriate

24 Michaud and Appio, p. 123.

25 David A. Kirby, Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2011), p. 44.

13

specialists from whom they obtain and synthesize scientific information, that they then translate into the language of cinema.’26 A boundary spanner then works directly with the film’s Art Department to share the scientific boundaries, or scope, which helps anchor creative ideation and provides guardrails for imagination

‘Alex McDowell’s job as production designer was to visualize an immersive fictional world, not to determine how or why this world came to be that way. For those issues he turned to John Underkoffler – the Boundary Spanner.’27 Underkoffler was far from a Hollywood film veteran He was an MIT PhD research student studying data representation and user interfaces (UI) It was precisely Underkoffler’s scientific expertise in this niche, and developing field, that helped inform McDowell and enable him to do his job. McDowell needed to be able to understand why and how something behaved in a future scenario. This insight enabled McDowell to develop the visualisations Scientific expertise, and the scenario planning, prefaced the resulting designs

One of Underkoffler’s main challenges in Minority Report was to explore how the main character, John Anderton (Cruise) engaged with computer interfaces in a gesture-based manner. While gestures such as “pinching”, “zooming” and “swiping” are commonplace today, they did not exist when the concepts were conceived Underkoffler approached the challenge as though it were a future world innovation research and development opportunity illustrating how scientific research served as the foundation for the future innovation.

“Underkoffler is well-aware of cinema’s ability to instill in the public a desire to see the realworld development of fictional technologies. In fact, he approaches every consulting opportunity with the explicit goal of creating cinematic technologies that enter the “technological imaginative vernacular” of real-world scientific discourse.”28

This approach necessitates development of a future world prototype. 26 Kirby, p. 44. 27 Kirby, p. 152. 28 Kirby, p. 199.

14

The Diegetic Prototype: Building an Authentic Scenario

There is a specific type of prototype classification for technological solutions that exist in future scenarios in film. ‘A diegetic prototype is defined as a cinematic depiction of future technologies in the fictional world. They exist as fully functioning objects in that world ’29 Put differently, the proposed future scenario and the proposed future innovation must become reality; they must be created

This is precisely what Underkoffler achieved with the gestural language and computer interface technology that would come to define Minority Report and inform the modern lexicon of User Experience (UX) and user interface design. The future innovative technology was built so that it could be used in the future world scenario that required it’s development. The diegetic prototype he created included supporting manuals and training videos for educating the cast on a common language ‘to foster public support for potential and emerging technologies by establishing the need, benevolence, and viability of these technologies’30 in a plausible future world scenario.

In Minority Report future scenario planning informs stories, which innovators then use to inspire engineering. It serves as a strong example for all innovators to model, that leverages speculative design and storytelling

This example illustrates how:

1. Science informs future scenarios;

2. Future scenarios inspire the development of technology through diegetic prototypes and;

3. Diegetic prototypes have the potential to become our future reality.

In this first section, we introduced and made the link between 2 well-known innovation theories to try and understand the connection between the exponential growth of computing power and individual’s propensity to adopt those innovations as they become available in the market

15

29 Kirby, p. 18.

30 Kirby, p. 18.

We explored innovation design methods, and suggested that the future world – or future scenario –must preface innovation and be used as a tool to inform the need for innovation.

And we reviewed how innovations come to life in pop-culture - in the form of science fiction, and its ability to bring future innovations into the present.

In the next section, we discuss the “shared dream” – the next step in the Evolution of Innovation framework

16

Anecdote: Mac vs. PC

It’s October 1, 2012. I’ve just moved to London to be with my partner. We have been in a long-distance relationship for 1 year. So, I decided, for the first time in my life, to throw caution to the wind, bet on love, and move overseas.

This meant that I needed to find a new job in a new country. Tt wasn’t difficult. The advertising scene in London was phenomenal. Within a month, I got 2 competing offers in one day. I was elated. I called my partner to share the news.

Roger: “Congratulations dear! I knew you could do it!”

Me: “I’m so excited! I can’t believe I have two offers! I’ve selected the job I want, and the contract will be coming through later this week.”

Roger: “That’s excellent. Did you ask them whether they are a Mac or PC shop?”

Me: “No, I didn’t. Don’t all advertising agencies use Macs?”

Roger: “No, not in London. Some use PCs. And some agencies split the allocation and give Macs only to the Creative Department and PCs to everyone else ”

Me: “Really? To be honest, I’d turn down a job if I knew the expectation was that I’d be required to use a PC I mean, I know they do the same thing, but it’s like the difference between writing in pencil vs. pen it comes across as unprofessional I wouldn’t take anyone seriously, from an advertising agency, if they showed up with a PC.”

Roger: “No need to stress, dear. Just tell your recruiter to negotiate a new Mac as a term in your contract.

17

Me: “Okay, that’s makes sense.”

Why did I think that way about these two brands?

When did I become a person that would turn down a job, if I didn’t get offered my preferred hardware?

Why did I consider one brand superior to the other, when I knew that both products accomplished the same goal?

I arrived at my new office for day 1. After a brief set of introductions to the team, I was ushered through to the IT department to get my computer set up.

IT Guy: “Hey, you’re the new hire today, right?”

Me: “Yes, that’s me. I was sent here to collect my machine.”

IT Guy: “So you’re the one who’s is getting a MacBook You must be in the Creative Department. Everyone is jealous of you guys. You’re the only department that gets MacBooks ”

Me: “Oh really? I’m not in the Creative Department, but I am getting a MacBook.”

IT Guy: “Really? How did you manage to get a Mac?! I’ve been trying to get one for years and I’m the person who orders all the computers. How the heck did you do it?!”

Me: “It’s all a part of the package.”

IT Guy: “Package? What package?”

Me: “Me. I’m the package. It’s a part of me.”

So, it would seem, I was not a lone ranger with my established set of brand values. I had become a “Mac Person.”

18

ACT II: The “Shared Dream”

This second section – the “Shared Dream” – makes the link between 3 well-known communications theories (Narrative Paradigm, Self-Concept Theory, Image Congruence Hypothesis), and suggests that a reasonable explanation for the diffusion of innovation maybe, at least in part, based on the image that technology projects, and attempts to explain how these converged theories, and their corresponding methods, come to life in society in the modern day in the form of brand stories. Finally, it proposes that second construct – the “shared dream” – is the important second ingredient in the innovation process.

The autoethnographic “Mac vs. PC” anecdote serves as a reminder of the connection between selfidentity and brand preference Our self-identity is mirrored in the brands that we choose to adopt, which is an important consideration when attempting to encourage the adoption of innovation in a shared dream. Why do people choose to adopt one brand over another?

The Narrative Paradigm: Communication is Story

Why do people choose to believe what they believe? Walter R. Fisher explored these concepts through the perspective of human communication. In his Narrative Paradigm a philosophy of reason, value, and action, he explored our relationship with each other, through narrative, first by looking at how we define ourselves as humans.

Homo Narrans: Human Storytellers

Fisher reframed humankind as ‘homo narrans’ storytellers who actively “recount” and “account” for human choice and action.’31 Recounting was attributed to stories by way of history, biography or autobiography, and accounting attributed with stories by way of theoretical explanation or arguments

He postulated that storytelling is responsible for what we believe in, as a part of the human condition.

31 Walter R. Fisher, Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action, Studies in Rhetoric - Communication, First paperb. Ed (Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina Pr, 1989), p. 62.

19

If stories are a part of what makes us human, the stories we believe in are too. They are a part of us. And they reveal a lot about character

Fisher surmised that ‘all forms of human communication need to be fundamentally seen as stories–symbolic interpretations of aspects of the world occurring in time and shaped by history, culture and character.’32 Those stories, or “forms of discourse,” should be considered as good reasons–values or value-laden warrants, for believing or acting in certain ways. He argued that a narrative logic – that all humans have by natural capacities to employ – ought to be conceived as of the logic by which human communication is assessed ’33 Put another way, we inherently assess the viability of a story – it comes naturally to us. In fact, it’s a part of being human Why are these considerations important when it comes to innovation and storytelling? Simply put, it comes down to designing a story that resonates.

Some stories present themselves as more believable than others – even the outlandish, future focussed stories, projected decades into the future Why are we inclined to believe in some, and not others, despite the fact both are fictious? Fisher believed that it comes down to the 2 principles of narrative logic: coherence and fidelity.’34 Coherence relates to our perception of the story as a whole, and fidelity relates to the sum of its parts. Together, they shape our assessment of whether or not ‘…the story represents accurate assertions about social reality, and thereby constitutes good reasons for belief of action.’35 We don’t discriminate between fictional and non-fictional stories – both need to pass our narrative logic litmus test in order to successfully shape our beliefs about reality and prompt action What we need to do is understand how to make them credible.

So, what does this mean when it comes to innovation and storytelling? If Fisher is correct, the diffusion of innovation has little to do with the product. If it is our human nature to believe (disbelieve) in a story based, on our coherence, and fidelity, it becomes necessary to design and communicate

32 Fisher, p. xiii.

33 Fisher, p. xiii.

34 Fisher, p. xiii.

35 Fisher, p. 105.

20

the innovation’s value set in addition to the innovative technology. Put another way: we crave brand stories because we wish to see ourselves reflected in them.

The Stories we Tell Ourselves and Why they Matter

Each of us has a personal set of self-beliefs about oneself ‘Self-Concept Theory is a person’s perception of one’s own abilities, limitations, appearance, and characteristics, including personality. According to Self-Concept Theory people act in ways that maintain and enhance their self-concept.’36

We all have our own self-narrative – we tell ourselves stories about ourselves every day. Our selfnarrative matters because it affects the way that we behave in more ways than we realise.

Sitting adjacent to the Self-Concept Theory is the Image Congruence Hypothesis which maintains that consumers prefer brands that have images like their own self-image ’37 We align ourselves with brands that we view as equal to our self-concept. At times, to elevate our perception of self, we associate with brands that we believe to be superior. It becomes apparent then, that the stories brands tell us, matter Alot. They affect whether we choose to engage with them or not, which in turn affects our willingness to adopt new technologies. We want to align ourselves with the values of brands we champion, alongside their innovative technologies.

Connecting the Dots: the “Shared Dream”

When we look at Narrative Paradigm, Self-Concept Theory, and Image Congruence Hypothesis collectively, we see some common threads begin to emerge. The Narrative Paradigm tells us that humans are connected through story. The Self-Concept Theory suggests that we view ourselves through our perceived self-image, and the Image Congruence Hypothesis tells us that we associate, and/or elevate, our self-image by associating with comparative or elevated brand images. For an innovation, seeking to gain acceptance in a market, this means communicating an image-based story.

36 Timothy R. Graeff, ‘Image Congruence Effects on Product Evaluations: The Role of Self-Monitoring and Public/Private Consumption’, Psychology & Marketing, 1966, p. 482 <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199608)13:5%3C481::AIDMAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-5> [accessed 5 June 2022].

37 Graeff, p. 481.

21

When it comes to the diffusion of innovation, brands, and the stories they tell that bring us together are critically important.

Branding, also referred to as “image advertising” focusses on positioning values alongside products and services ‘Image advertising sits at odds with traditional “hard sell”, or “product” based advertising, where audiences are given authoritative, rational reasons to choose one product or service over another.’38 In image advertising, audiences learn what a brand stands for, what is important to them, and why. Advertising, when executed in this way, means that consumers learn about a brand’s character and interpret it for themselves.

The Stories we are Told and Why they Matter

‘Branding’s emphasis on the use of image advertising, rather than on the rational-argument approach of product advertising, has the potential to offer each member of the audience a blank canvas to personally interpret the communication.’39 The audience isn’t being sold a product. Often, they don’t even see one in the story that’s being communicated Instead, they are being invited to share a common vision When it comes to establishing credibility for an innovative product with the goal of establishing advocacy, or a shared dream, the brand story must align to an aspirational set of values – specifically personality, and character.

Curiously, ‘what makes image advertising interesting is that it is often a rich, romanticized, complex series of visuals that may bear distant resemblance to what the business or its products will actually do for the consumer.’40 We see this sentiment illustrated in an iconic Super Bowl commercial. The Apple Super Bowl 60-second spot entitled ‘1984’ 41 borrows its dystopian plot from a classic science fiction novel, also entitled ‘1984’42 written by George Orwell. In the Apple 1984 spot, image

38 Graeff, p. 210.

39 Fisher, p. 212.

40 Nancy B. Stutts and Randolph T. Barker, ‘The Use of Narrative Paradigm Theory in Assessing Audience Value Conflict in Image Advertising’, Management Communication Quarterly, Vol. 13.No. 2 (1999), 209–44 (p. 220).

41 Ridley Scott, 1984 Apple Macintosh Commercial HD <YouTube, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugxGvg0KCxI>.

42 Nineteen Eighty-Four (London, England; New York, N.Y.: Penguin Audiobooks, 1996).

22

advertising is the key objective of the narrative. It serves as a strong example for all innovators to model, that leverages image advertising and storytelling.

Case Study: 1984

Apple wasn’t always a leader. They were considered the underdog. This was the case in 1984, when IBM dominated the personal computing industry. But Apple, and Steve Jobs had an individual dream, one that they, and he, now wanted to share with the world.

Apple envisioned a world where computers were intuitive, fostered a sense of creativity and imagination. This ideology sat in stark contrast to the strategy IBM was executing in the mid-eighties. IBM had positioned themselves, and personal computers, as machines, and their customers were becoming dependent on their utility.

Story as Scenario: The Future World and its Future Values

Almost 40 years earlier, this dystopian future was brought to life by George Orwell in the literary classic of the same name. In Orwell’s novel, the people of earth are controlled by Big Brother: the masses, mindlessly subservient, obeying instructions, and staring at a screen.

This iconic literary reference – a story – resonated with the world. Apple aligned the values of their competition with this “Big Brother” mentality, and in the process, positioned themselves as a brand with a different (superior) set of values existing in this future world scenario

The Brand Story: Sharing the Dream

Apple’s 1984 launched the new Macintosh computer – the newest, most innovative personal computer ever. It was a technological marvel, but the commercial didn’t include the product. Instead, IBM users were portrayed as mindless automatons, and Apple users as fresh-faced, athletic, and youthful, clad in white and bright orange A woman races towards the machine with vigour, swings a sledgehammer, and shattered the screen and Big Brother (IBM) In this one hammer-toss, Apple became the iconoclast.

23

“On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like “1984.”

The Apple Mac launch was a product launch, without a product. But it sold so much more: a brand story and shared dream It was the unofficial beginning of disruption in the personal computer industry. Apple waged war with IBM, the industry leader. It was a classic David and Goliath story, with a twist – the customer, at the centre, being forced to reckon with their near-inevitable fate. But not if they chose wisely. Or had Apply chosen them?

Within 100 days, Apple sold 72,000 computers. Fifty-percent more than its most optimistic sales target. An undoubted triumph. But the success of this campaign established victory on a different front: brand and image.

Apple and IBM would continue to wage their brand image war, by way of storytelling, for decades to come. But the seeds had been sown and, despite their best efforts, IBM couldn’t shake their image as the dowdy office worker; the mindless corporate consulting-bot.

Apple branded their image – creative, cool, and youthful – in 60-seconds one Super Bowl Sunday

and it stuck for life The shared dream had been established, and people were aligning their selfidentity with a brand whose story they wanted to be a part of. To a fictional future that they wished to become true. And so, it did.

And, looking back, perhaps that’s why selecting hardware in my new job was so important. I believed in this brand image, too. Apple fundamentally represented who I was as a professional in the advertising industry. It was synonymous with success – at least in my eyes.

This example illustrates how:

1. The future scenario is a classic science fiction story;

2. Future scenarios must present value systems that inspire innovative products and;

24

–

3. People align themselves with beliefs, as well as products, and those values alone are necessary, but not sufficient for the diffusion of innovation to inspire a future reality.

To recap this second section – the “Shared Dream” – we made the link between 3 well-known communications theories, and suggested that storytelling is the fundamental way that we communicate as humans.

We explored the self-narrative, and the stories that brands tell us through image advertising, and we proposed that a set of brand values should be established and communicated when making the important, and critical second step, to share a dream.

And we reviewed how brand values are successfully communicated through to an audience, in the Apple Super Bowl commercial, 1984.

In the next section, we will discuss the “reality” – the next step in the Evolution of Innovation framework

25

Anecdote: Seeing is Believing

I’d spent the better part of my career in digital advertising and (accidentally) become specialised in financial services After spending several years running global innovation programmes for one of the biggest financial brands in the world, I had a new opportunity. I was selected to be part of a small team establishing a new office in Singapore. This team would be responsible for digital innovation in Asia Pacific, for one of the world’s most admired global banks.

Though small initially, we would be supported by our larger global network with access to a range of resources and talent – all things that we would need in order to make this new office a success. We worked round the clock, time-zones blurred between EMEA, North America and LATAM. At any given moment, I knew what time it was in at least 5 other countries.

One day, quite early in our tenure there, our humble team was called in to help our most important client out of a very challenging situation. His team had spent several years trying to tackle a “wicked problem,” but they were failing. We were given 2-months to cover ground that they had spent 2 years tackling.

We called in support from across the globe. Colleagues and partners alike collaborated to help us make our vision and our clients shared dream – a reality And all eyes were on us, and we needed to deliver this critically important, new, and innovative service. A first of its kind in Asia Pacific and the world over.

We imagined a future scenario, a speculative design, and a suite of technological interventions The final stretch was intense, with the team working a 48-hours shift. But we were finally done Everything was stitched together in a story and presented in a video that lasted about 90-seconds.

I was happy, and exhausted. But I couldn’t have anticipated what would happen next.

26

Our client – let’s call him F.B. – loved the video.

So much so in fact, that he started sharing it with colleagues around the world. He shared it first, locally, in Singapore. And within minutes, the audience grew to include Australia, Hong Kong, and New York.

F.B.’s colleagues loved the video too. So much so that they started sharing it with their colleagues around the world. Our 90-second “confidential” concept video was going viral.

And then the phone rang. It was F.B.

“Everyone loves this video; everyone wants to see it. The problem is, we can’t let the competition get their hands on it. We need to make this dream a reality. I already have 4 countries on board. But we need to pull the video.”

I made a quick call to Chicago, who were 11 hours behind. No answer. I hunted the globe to find someone in IT with access to the server. Before long, I had the file removed.

F.B.’s 90-seconds of dreaming now needed to become reality. A global reality. And perhaps, most challengingly for us – everyone believed that our speculative new service was real. And they were falling all over themselves to adopt it

27

ACT III: The “Reality”

This third section – “Reality” – makes link between technological innovators and 2 forms of innovative design tools (design fiction, concept design) and suggests that a reasonable explanation for dreams to become reality, and eventually technology in the hands of consumers, may at least in part, be based on the way that these design tools are integrated into a story In other words, as standalone artifacts, they are somewhat less impactful – they need a collective platform – and story provides that platform Finally, it proposes that the third construct – “Reality” – is the important third ingredient in the innovation process.

The autoethnographic “Seeing is Believing” anecdote involving F.B. reminds us that bringing a conceptual design to life involves the application – not only of design (tools, methods, etc.) – but of storytelling. How do futurists bring their ideas into the present day? How does one set out to build an innovative technology – something that doesn’t yet exist and is being developed based on a hypothetical future need? Why do some brands make us believe – even when their products and services leave much to be desired? A mythical creature from history may have the answer.

Unicorns: Alive in the Modern Day

We need look no further than The Wright Brothers, Bell, or Edison to see that invention, and innovation are common throughout our history. Innovation has always had the potential to make our future brighter, and when paired with a compelling story, to fulfil needs that we didn’t know that we had. Today’s, innovators have reached, and arguably surpassed, the iconic statuses achieved by their innovative predecessors The Unicorn: once mythical creatures of lore, in today’s lexicon, “Unicorn” means something different. A term coined in 2013 by venture capital Aileen Lee, ‘Unicorns are defined as privately held companies valued at more than $1 billion,’43 with no profit. Less than a decade ago, Unicorns were a rarity, with a total of 39 start-ups’44 meeting this valuation criteria,

43 ‘PitchBook Blog’, What Is a Unicorn Company?, 2022 <https://pitchbook.com/blog/what-is-aunicorn> [accessed 15 May 2022].

44 Scott Carey, ‘Tech Advisor’, What Is a Tech Unicorn? And Where Did the Term Come From?, 2018 <https://www.techadvisor.com/feature/small-business/what-is-tech-unicorn-3788654/>.

28

globally. Fast forward to March 2022, and there are ‘estimated to be 607 companies around the world.’45 What is responsible for the success that modern-day innovators have in making their dreams a reality? Is this a historical blip, or something more?

As it turns out, this is no “blip.” The unicorn population continues to grow at a rapid rate. ‘Tech companies today are now receiving higher valuations than at any other time in recent history, in far less time. The average time for a company to reach a $1 billion valuation between 2000-2003 was 8.5 years. This dropped to 2.9 years between 2009-2013 according to research by the consultancy firm Play Bigger.’46 What once seemed impossible, reaching a $1 billion valuation, is now, fairly routine

The multi-layered lexicon of evolving Unicorn terminology implies a story of continued growth and success. ‘There is the collective noun: a herd or blessing of unicorns, normally grouped around an industry, a specific fund, or geography. Then, there is the decacorn: Companies valued above $10 billion. Think Uber ($62bn), Airbnb ($25bn) and Dropbox ($10bn). Then there is the super-unicorn (<100bn): Think Facebook before going public in 2012.’47 Once, a rarity was defined as $1 billion dollar valuation, and now several of the “original” Unicorns are exceeding this amount in multiples of 10, to 100 times over

The growth lexicon is contrasted with a mere single identifier of failure, albeit harsh, the dead Unicorn. ‘Defined as a graveyard of billion-dollar valued companies that have stalled on the fast-track to an Initial Public Offering (IPO) due to softening investor confidence or stalling user numbers.’48 Read that again, softening investor confidence. Confidence. Not failed technology. Which begs the question, what perpetuates confidence in innovation? As this thesis has argued, technological innovation alone cannot be the answer. It doesn’t take more than a quick look around to imagine that stories might be playing an equal, and critical hand.

45 ‘PitchBook Blog’.

46 Carey, ‘Tech Advisor’.

47 Scott Carey, ‘What Is a Tech Unicorn? And Where Did the Term Come From?’, TechAdvisor, 18 April 2016 <https://www.techadvisor.com/feature/small-business/what-is-tech-unicorn-3788654/>.

48 Carey, ‘Tech Advisor’.

29

Design Fiction & Conceptual Design: Seeing is Believing

When innovators are looking to take a shared dream into reality, they turn to another narrative tool used in speculative design: design fiction. ‘Design fiction employs speculative products and prototypes to anticipate future trends or propose visionary solutions to vexing problems. Some design fictions depict gleaming futures filled with tech-enabled products, while others imagine darker outcomes.’49 Perhaps one could consider design fiction to be a close cousin to science fiction, in that it places technology in the future. The difference, however, is how both design disciplines accomplish this feat.

Design fiction is brought to life through conceptual design. ‘Conceptual designs are not only ideas but also ideals. And as the moral philosopher Susan Neiman points out, ‘we should measure reality against ideals, not the other way around.‘50 Conceptual design brings the vison to life in the physical form. Certainly, deemed abstract, and no-doubt a collection of imaginary ideas, it manifests into the physical. Not meant for production, nor even customer use, the conceptual design serves a different purpose.

Conceptual design nudges a dream through the Innovation of Evolution framework ‘It uses abstraction together with general technical references, to suggest a strange technological device.’51 It presents the possibility of reality by giving form to imagined technological function.

Pulling the Puzzle Together with Design Fiction & Concept Design

When we look at design fiction and concept design, we can see their independent contributions to future technological advancements. They each serve an important purpose in innovation – they give form to imaginative future technology. But giving form to imagination is necessary, when it comes to making dreams a reality, bringing new innovations to market, and having them adopted.

49 Ellen Lupton, Design Is Storytelling (New York, NY: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2017), p. 50.

50 Dunne and Raby, p. 12.

51 Dunne and Raby, p. 12.

30

When it comes to making dreams a reality, story offers that needed form. If we consider the Narrative Paradigm, and the notion that humans inherently have an ability to believe (or disbelieve) a story, it becomes critical to place futuristic – and arguably unreal – artifacts in a place that positions them with narrative logic, so that they pass the tests of coherence and fidelity. Put another way, without stories innovation fails.

When we revisit the autoethnographic “Seeing is Believing” anecdote and consider the fact that F.B. had invested 2 years in solving a wicked problem, but continued to fail, we see the assertion that stories power innovation laid bare. My team approached the challenge in a different way: by pulling the design fiction, and concepts together, through a story, presented in video, in under 2 months. The contrast in response and perception is unquestionable Story works. It was, and is, indeed the missing element required to turn F.B.s dreams into reality.

If story then, is the foundational element required to convert design fiction and concept design, into innovation, do we need functioning innovation to be successful? Are stories alone, paired with imagination and an admirable combination of vision, mission, purpose, character, and charisma, enough for an innovator to be successful in the technology industry, and for that innovation to be widely adopted and become part of culture? In this final section, this thesis explores that possibility.

Case Study: Theranos

Elizabeth Holmes was a bio-technology entrepreneur. A nineteen-year-old Stanford University drop out who in ten years became Silicon Valley’s first female billionaire entrepreneur and, the first female to lead a Unicorn. How? Holmes used a combination of design fiction, conceptual design, and storytelling to build the Theranos empire.

At face value, Theranos’ story was incredible: Eradicate disease, make healthcare accessible, and develop a proactive approach to disease prevention with easy-to-access, and crucially easy to administer, blood tests. Theranos’s story resonated with every man, woman and child who ever winged at the thought of a needle.

31

As any American will attest, only the wealthy can afford to get sick in America. Theranos struck a chord, with not just a segment, but an entire nation. And that nation desperately wanted this dream to become a reality.

Introducing Edison (Junior)

Central to Holmes’ success was the Edison, a prototype developed by Theranos and touted as the blood analyser of the future. Its namesake inspired by none other than, the archetypal inventor and innovator, Edison.

Holmes chose this name because, “We tried everything else, and it failed, so [we called] it the Edison.”52

In doing so, Holmes instantly leveraged the credibility associated with one of America’s most famous inventors and Founding Father’s. She also set herself up to excuse any impediments that may be deemed “failures” and test the “confidence” of any investors on her journey

Edison the machine, offered an enticing value proposition: no more needles. Gone were the days of painful blood draws and collapsed veins. In their place, Homes imagined a “nanotainer”, a small device that required only a few droplets of blood to conduct a battery of tests – called “immunoassays.” A viable need – equally, something no one knew they needed, but suddenly something everyone wanted to be a reality.

Edison Meets the World

Holmes took Edison on the road, telling her story, converting cities to supporters – giving them a part to play in her shared story, and in doing so, converting a nation’s shared dream to reality In Holmes’ future, any chemist could offer same-day ‘nanotainer’ blood draws for their customers with instant results. Before long, ‘Theranos Wellness Centres’ were popping in Walgreens stores across America

52 Corey Steig, ‘What Exactly Was the Theranos Edison Machine Supposed to Do?’, Health News, 2019 <https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2019/03/224904/theranos-edison-machine-blood-testtechnology-explained> [accessed 8 June 2022].

32

It was a compelling story, that attracted global attention – everyone was excited for this new dream to become a reality And if Holmes, and her All-Star Board would have their ways, it would soon come true across the Unites States of America

A Look Under the Hood

But what was Edison really? A bio-tech marvel or an imaginative piece of speculative design – a concept brought to life as a “functioning” prototype. Unfortunately, we know how this story ends.

The Edison didn’t live up to its claim. Work arounds involving traditional needles for blood draws alongside the Edison soon became the norm. A parallel system was put in place where traditional blood draws – those requiring needles – were done in tandem and shipped to Theranos’ traditional laboratories in order to conduct traditional, even routine, tests.

But were these inconveniences just a growing pain – the cost of innovation? Thomas Edison certainly claimed to have experienced a similar challenge in the face of innovation, being famously quoted as saying “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that don’t work.” Failure was necessary, according to Holmes, as she excused the inconvenience. ‘People forget that Icarus also flew. Perhaps he was not failing when he fell – but rather coming to the end of his triumph.’ 53

The End of Holmes’ Triumph

Eventually, technology would catch up with Holmes and Theranos would be outed as one of the most elaborate, and profitable, forms of innovative storytelling in Silicon Valley. This is important because: it illustrates that Silicon Valley accepts innovation that is predicated on storytelling And not only does it do so, but this anecdote also shows that it values stories at least as an equal contributor to a Unicorn’s success. ‘Holmes channelled the “fake-it-until-you-make-it” culture. The extreme bordering on fakery ’54 Theranos is indeed a storytelling masterpiece that convinced many of the world’s most

53 Lela Gilbert, The Levine Affair: Angels Flight (Place of publication not identified: Post Hill Press, 2014).

54 John Carreyrou, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (London: Picador, 2019).

33

renowned, most respected, and most revered industry veterans who, all unknowingly, gave narrative logic (coherence and fidelity) to Holmes’ audience. While she became the leading lady in her own life story, and the world was her stage.

Reflecting on my own experience with F.B., bringing a fictional prototype into reality – and having it go viral – is helpful because, it gives credence to the notion that the imaginary must be brought into the real, or perceived real, as a necessary step in the Evolution of Innovation framework. In other words, stories are tools that bring ideas to life. We all want our own piece of reality.

This example illustrates how:

1. Design Fiction and Concept Design come together by way of prototypes;

2. Prototypes socialised with the world help transition the imaginary into reality and;

3. Storytelling in Silicon Valley is considered a must-have requirement for technological innovation

So, what have we learned so far? Let’s check-in. In this third section, “Reality,” explored how Unicorns, the inventors of the 21st Century, made the link between 2 well-known design practices, and argued that storytelling is a must-have requirement, a magical, mythical ingredient, when it comes to the diffusion of innovation. Stories are what make shared dreams become our reality.

What’s more, this thesis argues that successful innovation is largely a storytelling exercise, and in the final section, this essay will discuss how “reality” becomes a “shared reality” – the final step in the Evolution of Innovation framework.

34

Anecdote: The Pitch

In 2015, I was hired to work in a new digital practice for a financial consulting firm in New York City. I would be working right on Wall Street. My dream to live in New York City was becoming a reality.

My team was preparing for one of our first pitches. It was a pretty big deal. The global COO wanted a dry run on the presentation 48-hours before the client presentation. The leads of each department gathered, and we presented the work. We were proposing a suite of innovative financial services that, we believed, needed to be created. The presentation included future scenarios with challenges to be solved. We incorporated innovative technological solutions in a comprehensive system and wrapped it all up in a nice bow. It was a compelling and inspiring story

The COO listened intently, and after the presentation, gave the green light. Everyone smiled. We’d passed the first hurdle.

“Who’s going to be in the room presenting?” He questioned.

“We need someone with tattoos. Do we have someone with tattoos?”

He paused, realising that everyone was looking at him bewildered, and addressed the room.

“Listen guys, we created a great story on what new innovative financial services need to be created. But it does no good if we are the only ones who believe in this dream. To make it a reality, we need to cast the room to demonstrate the shared appeal this has to a broader audience. We need everyone to believe that this thing should be brought to life.”

We got it. We understood. And thankfully, Roger had tattoos. And lots of them. He was leading the pitch, and all that he needed to do, was roll up his sleeves.

35

Introduction: The “Shared Reality”

The autoethnographic “The Pitch” anecdote reminds us of the importance of bringing a realized innovation to a mass audience to establish true industry disruption. The innovation technologies that are introduced to society, and have fundamentally changed the way that we live, and continue to do so at an accelerated pace, proves this can be done on repeat, if the right care and attention is given to each step in the Evolution of Innovation framework.

How do futurists establish mass adoption for an innovation that has yet to be established long-term in the market? How does technology resist becoming obsolete, or overtaken by a copycat entrant in the market?

Storytelling: Lessons Learned through Prequels and Sequels

Tribes, groups of people who lived together and shared the same language and values, existed long before the introduction of written laws. In tribal days, storytelling was the tool used to maintain order

According to Will Storr, ‘we've spent more than ninety-five percent of our time on earth existing in such tribes and much of the neural architecture we carry around today evolved when we were doing so.’ A neural network is how we form thought patterns which become the foundation of our value system. It seems reasonable to suggest that our tribal brains were conditioned to learn our values through storytelling. But what happens with an evolving narrative, such as that presented through the Evolution of Innovation framework?

Fisher’s Narrative Paradigm might explain how humans evolved to process an evolving narrative and alludes to the importance of tribal mentality. ‘From infancy,’ Fisher argues that ‘we interpret and evaluate new stories against older stories acquired through experience. And that we search new accounts for their faithfulness relative to what we know, or think that we know, and for their internal and external coherence.”55 Put another way, our narrative logic – our innate ability to deduce coherence and fidelity – is compounding Meaning it considers past stories. This is important when it

55 Fisher, p. ix.

36

comes to the understanding in the Evolution of Innovation framework. We consider the entirety of the story as a collective – like chapters in a book

And according to Fisher, we get better at this over time. He states that, ‘Later we learn more sophisticated criteria and standards for assessing a story’s fidelity and coherence, but constructing, interpreting and evaluating discourse as “story” remains our primary, innate, species-specific “logic.”’56 It is the central argument of this thesis that this logic is represented in the Innovation of Evolution framework. The successful advancement from one stage to the next, requires a successful prequel.

What’s more, as the story progresses it becomes more elaborate – including several types of design, artifacts, and props by way of prototypes These sequels are necessary to appeal to our own evolving level of sophistication in assessing narrative fidelity and coherence So, how do we successfully share our reality with the tribe we formed? In this work’s final act, we explore what it means to become “The Hero ”

The Hero’s Quest: The Brand becomes the Hero

Everyone loves a hero. What’s often not considered, is why we love them. ‘The child identifies with the good hero not because of his goodness, but because the hero's condition makes a deep positive appeal to him/her. The question for the child is not, "Do I want to be good?" but "Who do I want to be like?"’57 This same sentiment is echoed in the Self-Concept Theory. People act in ways that maintain and enhance their self-concept. We align ourselves with things that represent who, or what we want to be.

It follows logically therefore, that a brand must become the image of a hero in the eyes of their customer. It’s worth noting that heroes aren't perfect humans, nor should they be. They are flawed, just like the rest of us. It's through these very flaws that we better understand their raison d’être. With that understanding comes, a sense of compassion and empathy. In fact, once we understand our

56 Fisher, p. ix.

57 Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling, Paperback edition (London: William Collins, 2020), p. 164.

37

hero’s behaviour we become their advocate – rationalizing why they did (or did not) do something.

Advocacy equates to loyalty

The Unwritten 4th Act – Loyalty

Every hero needs a villain just as every story needs an antagonist. Without them, we wouldn’t have a scenario to create a value system based on behavioural responses. ‘Archetypal stories about antiheroes often end with them being killed or otherwise humiliated, thus serving their purpose as tribal propaganda. We're taught the appropriate lesson and left in no doubt about the costs of such selfish behaviour.’58 It’s through the actions of the anti-hero that one learns accepted tribal behaviour.

Steve Jobs understood this all too well at Apple. Jobs said famously ”The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values and agenda of an entire generation that is to come.” Jobs employed the rule of threes in his storytelling.’59 It’s a common framework used by Hollywood. It includes Act I: Setup, Act II: Confrontation and Act III: Resolution.

In Act I, the main character is introduced, along with the plot and ultimately a set of challenges. In Act II, the character explores the challenges in further detail and develops logical plans to tackle the situations presented. In Act III, the audience is given plausible remedies and perspective on why the character choses a certain path. What Jobs may or may not have realized, was this would result in an unwritten Act IV – The loyal follower – and stories of the brand ambassadors amassed who shared the same belief.

We see this come to life in Apple’s the infamous image advertising ‘Get a Mac.’

58 Storr, p. 169.

59 ‘Steve Jobs Followed a Simple 3-Step Formula for All of His Speeches’ <https://www.businessinsider.com/steve-jobs-followed-a-simple-3-step-formula-for-all-of-hisspeeches-2016-4?r=US&IR=T> [accessed 12 January 2022].

38

Case Study: ‘Get a Mac’

Apple ran their infamous ‘Get a Mac’60 campaign between 2006 to 2009 An entertaining campaign –including 66 commercials – featuring two actors personifying two types of computers: Justin Long, as Mac, and John Hodgman as PC.

The campaign had standardised its format which included a consistent opening: two actors standing side-by-side, introduced themselves:

Long: “Hi, I’m a Mac” Hodgman: “…And I’m a PC”

From there, banter ensued. The nonchalant, laid back and ever chill Mac (Long) would strike up a conversation to chat with friend PC (Hodgman) and see how he was doing. Undoubtedly, this exchange would reveal some challenging ‘hardships’ or ‘bugs’ in PC’s life. Mac, ever the optimist, tried to console his friend, while also giving an update on his current life events – which were naturally quite positive.

This campaign did not feature products in the traditional sense. Instead, image advertising was used to create tribes in the personal computer industry. Before long, people began identifying as either a Mac user or PC user. You simply weren’t both – you were one or the other.

As expected, Mac (Long), emerged as the hero in the sketch. His success largely guided by a set of idealistic values – represented by Apple.

This example illustrates how:

1. Image advertising can be used to created tribes,

2. Heroes emerge based on a set of values and belief system – which serve as a north star and;

3. Brand loyalty is established by your values and belief system, not the product you sell. 60 Complete 66 Mac vs PC Ads, 2012 <YouTube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0eEG5LVXdKo>> [accessed 3 June 2022].

39

Looking back at my own experience pitching to a potential client, I see the opportunity and value of creating tribes in a variety of settings: from the team creating the concepts, to the team presenting and, the clients themselves. Each tribe has its own set of values and beliefs – understanding what those values are and being able to deliver upon them – sets the stage for one to become a hero figure in that tribe and ultimately, influence behaviour

This fourth and final section – “Shared Reality” – makes link between 3 well-known communications theories (Narrative Paradigm, Self-Concept Theory, Image Congruence Hypothesis), and establishes the importance of tribes and heroes to create brand loyalty

Finally, we reviewed how a hero can become a leader of a tribe in the Apple campaign, “Get a Mac” and proposed that the fourth construct – the “shared reality” – is the important final ingredient in the innovation process.

40

Closing Reflections

This journey started with a rather curious quest: to explore whether innovation would be successful without story. The approach taken to explore this question was diverse. It considered:

(1) Academia and the merging of theories from the most intelligent minds in the spheres of communication and technology;

(2) Case studies analysis to critically assessing technology giants successful (and unsuccessful) quests to disrupt industries with innovative technology;

(3) Anecdotal self-ethnographic narratives to prompt self-reflection on personal experiences in the industry.

What has become evident, is that technology is indeed necessary for story to be successful, but in more capacities than originally considered. Story is needed not only for the innovative products and services, but arguably more so, for the innovators themselves, not only to introduce new products and service to the masses, but also as tool to help advance their belief system towards technology itself, and influence the masses

Put another way, when it comes to innovation, story does matters. But it also matters for innovators, and more broadly, for society as a whole

41

Bibliography

Carey, Scott, ‘What Is a Tech Unicorn? And Where Did the Term Come From?’, TechAdvisor, 18 April 2016 <https://www.techadvisor.com/feature/small-business/what-is-tech-unicorn3788654/>

Carreyrou, John, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (London: Picador, 2019)

Chang, Heewon, Autoethnography as Method, Developing Qualitative Inquiry, v. 1 (Walnut Creek, Calif: Left Coast Press, 2008)

Complete 66 Mac vs PC Ads, 2012 <YouTube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0eEG5LVXdKo>>

[accessed 3 June 2022]

Davis, Nicholas, ‘World Economic Forum’, What Is the Fourth Industrial Revolution?, 2016

<https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/what-is-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/>

[accessed 2 June 2022]

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London: The MIT Press, 2013)

Fisher, Walter R., Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action, Studies in Rhetoric - Communication, First paperb. Ed (Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina Pr, 1989)

‘Futurist’, Cambridge Dictionary (Cambridge University Press 2022)

<https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/futurist>

Gilbert, Lela, The Levine Affair: Angels Flight (Place of publication not identified: Post Hill Press, 2014)

Graeff, Timothy R., ‘Image Congruence Effects on Product Evaluations: The Role of Self-Monitoring and Public/Private Consumption’, Psychology & Marketing, 1966

<https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199608)13:5%3C481::AIDMAR3%3E3.0.CO;2-5> [accessed 5 June 2022]

Gunn, James E., The Road to Science-Fiction (Lanham (Md.) Oxford (GB): the Scarecrow press, 2002)

Hanington, Bruce, and Bella Martin, Universal Methods of Design Expanded and Revised (Beverly: Rockport Publishers, 2019)

Kirby, David A., Lab Coats in Hollywood: Science, Scientists, and Cinema (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2011)

Lupton, Ellen, Design Is Storytelling (New York, NY: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2017)

Michaud, Thomas, and Francesco Paolo Appio, ‘Envisioning Innovation Opportunities through Science Fiction’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 39.2 (2022), 121–31

<https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12613>

42

Moore, Gordon E., ‘Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits, Reprinted from Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965, Pp.114 Ff.’, IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter, 11.3 (2006), 33–35 <https://doi.org/10.1109/N-SSC.2006.4785860>

Muratovski, Gjoko, Research for Designers: A Guide to Methods and Practice (London: Sage Publications, 2016)

Nancy B. Stutts, and Randolph T. Barker, ‘The Use of Narrative Paradigm Theory in Assessing Audience Value Conflict in Image Advertising’, Management Communication Quarterly, Vol. 13.No. 2 (1999), 209–44

Nineteen Eighty-Four (London, England; New York, N.Y.: Penguin Audiobooks, 1996)

‘PitchBook Blog’, What Is a Unicorn Company?, 2022 <https://pitchbook.com/blog/what-is-a-unicorn> [accessed 15 May 2022]

Rogers, Everett M., Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed (New York: Free Press, 2003)

Scott, Ridley, 1984 Apple Macintosh Commercial HD <YouTube, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ugxGvg0KCxI>>

Spielberg, Steven, Minority Report (20th Century Studios, DreamWorks Pictures) <iTunes <https://itunes.apple.com/gb/movie/minority-report/id573718569>> [accessed 28 May 2022]

Spielberg, Steven, Minority Report - You Don’t Choose the Things You Believe In (20th Century Studios, DreamWorks Pictures, 2002) <YouTube, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AuGw8MSmjk>> [accessed 21 May 2022]

Steig, Corey, ‘What Exactly Was the Theranos Edison Machine Supposed to Do?’, Health News, 2019

<https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2019/03/224904/theranos-edison-machine-bloodtest-technology-explained> [accessed 8 June 2022]

‘Steve Jobs Followed a Simple 3-Step Formula for All of His Speeches’

<https://www.businessinsider.com/steve-jobs-followed-a-simple-3-step-formula-for-all-of-hisspeeches-2016-4?r=US&IR=T> [accessed 12 January 2022]

Stickdorn, Marc, Adam Lawrence, Markus Hormess, Jakob Schneider, and Marc Stickdorn, This Is Service Design Methods, a Companion to This Is Service Design Doing: Expanded Service Design Thinking Methods for Real Projects, First edition (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc, 2018)

Storr, Will, The Science of Storytelling, Paperback edition (London: William Collins, 2020)

43