featuring the winner of the laux / millar poetry prize

new poetry by colin bailes, allison blevins, mary buchinger, caroline chavatel, julia kolchinsky dasbach, joshua davis, gregory djanikian, j.r. evans, grace ezra, loisa fenichell, c. francis fisher, stephanie kaylor, peter laberge, justin lacour, cass lintz, owen mcleod, anne dyer stuart

and fiction from erica jenks henry, katherine joshi, andrea lewis, caroline mccoy, john salter, mackenzie sanders

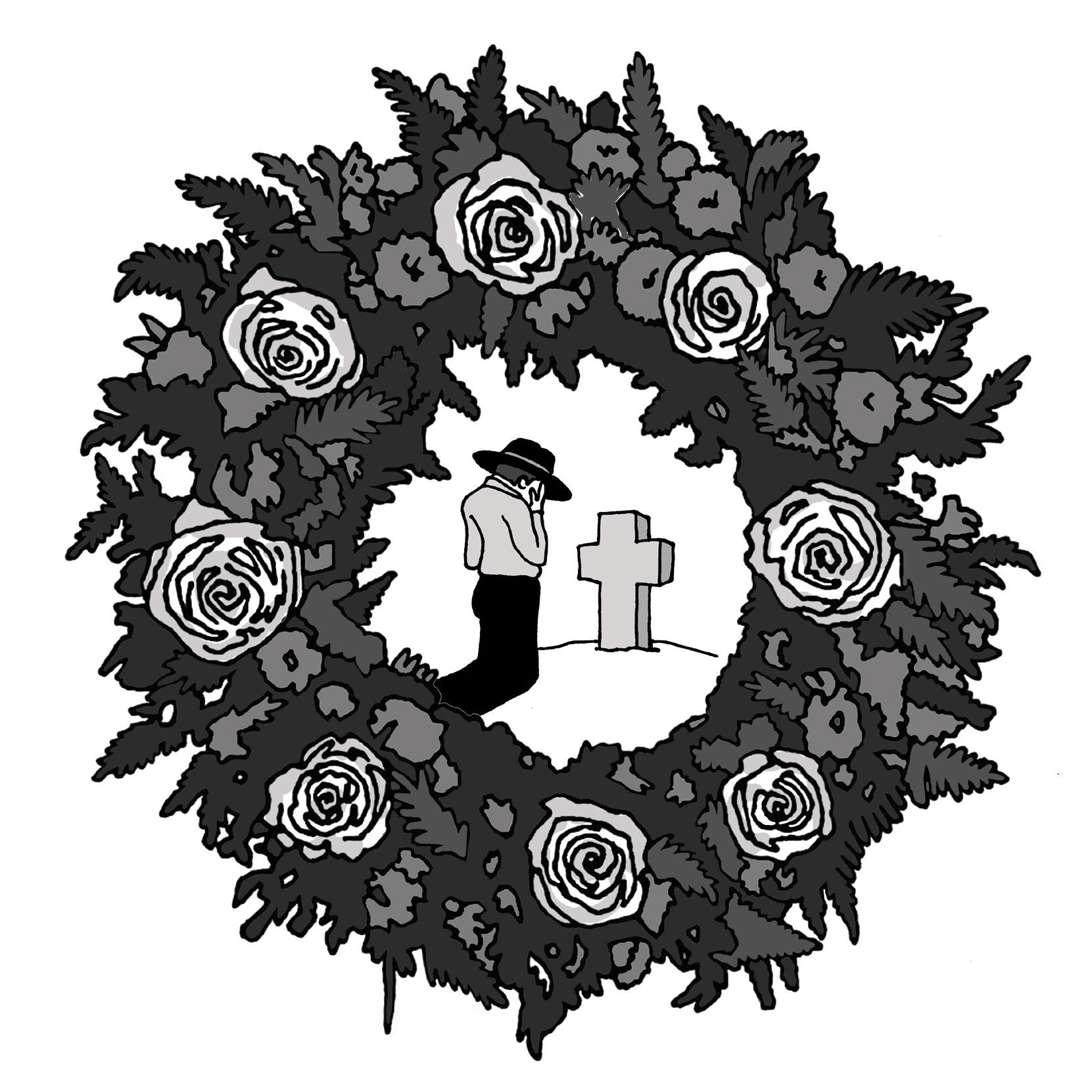

featuring illustrations by nora kelly

“The night after my father’s body slid into its oven, / not at all like bread, / with none of its promise, // I wanted to make someone pregnant.”

— from allison blevins & joshua davis’ “ the fever’s children ” winner, laux / millar poetry prize

vol. 12.2, Fall 2022 RALEIGH REVIEW vol. 12.2, Fall 2022

2013 9 780990 752288 5 2 0 0 0 > ISBN 978-0-9907522-8-8 $20.00

RALEIGH REVIEW

RALEIGH REVIEW

vol. 12.2 fall 2022

RALEIGH REVIEW VOL. 12.2 fall 2022

publisher

Rob Greene

co-editors

Bryce Emley

Landon Houle

fiction editor

Jessica Pitchford

poetry editor

Leah Poole Osowski

editorial staff / fiction

Dailihana Alfonseca, Chas Carey, Madison Cyr, Susan Finch, Robert McCready, Jeff McLaughlin, Erin Osborne, Daniel Tam-Claiborne

board of directors

Joseph Millar, Chairman

Dorianne Laux, Vice Chair

Landon Houle, Member

Bryce Emley, Member

Will Badger, Member

Tyree Daye, Member

Rob Greene, Member

assistant fiction editor

Shelley Senai

assistant poetry editor

Tyree Daye

consulting poetry editor

Leila Chatti

copyeditor

Garrett Davis

editorial staff / poetry

Ina Cariño, Chelsea Harlan, D. Eric Parkison, Sam Piccone

Melanie Tafejian, Annie Woodford

illustrator

Nora Kelly

layout & page design

Alexis Olson

literary publishing program interns

Chris Ingram

Jeremee Jeter

Da'Jah Jordan

Raleigh Review, Vol. 12, No. 2, Fall 2022

Copyright © 2022 by Raleigh Review

Raleigh Review founded as RIG Poetry

February 21, 2010 | Robert Ian Greene

Cover image " Haiku Collage" by Christine Kouwenhoven. Cover design by Alexis Olson

ISSN: 2169-3943

Printed, bound, and shipped via Alphagraphics in Downtown Raleigh, NC, USA.

Raleigh Review, PO Box 6725, Raleigh, NC 27628 Visit: raleighreview.org

Raleigh Review is thankful for past support from the United Arts Council of Raleigh & Wake County with funds from the United Arts Campaign, as well as the North Carolina Arts Council, a division of the Department of Cultural Resources.

[For years I believed…]

To our firsts The Fever’s Children

fiction john salter caroline mccoy katherine joshi erica jenks henry mackenzie sanders andrea lewis poetry gregory djanikian stephanie kaylor colin bailes allison blevins & joshua davis 11 22 34 60 79 93 1 4 5 6 7 14 16 table of contents Kilowatts Swept Away Burning Aunt Mary Open Range Radiant Later Years

Memoriam Telescope Book of Parables

raleigh review

Another name for weather

Touching

The first letter at the beginning of the end

Dayshift at the Place of Safekeeping

Sonnet for Use Value

Failed Sonnet: The Money Feeds Us

How to do it

Afterlife

Friday, 9:59 p.m.

Sunday, 1:04 p.m.

Friday, 8:37 a.m.

Saturday, 4:00 p.m

poetry cont. loisa fenichell julia kolchinsky dasbach owen mcleod caroline chavatel j.r. evans c. francis fisher justin lacour anne dyer stuart peter laberge mary buchinger

Fourteen Summers Stripping Incendiary 17 18 19 55 56 57 58 59 75 76 77 78 88 89 98

poetry cont. grace ezra cass lintz contributors 91 92 98 I am told again that I am not gentle Send Me Something Else Tour of Separations

vol. 12.2 fall 2022

raleigh review

from the editor

i like to think of telling the truth and being honest as two different things. Telling the truth is a straight line from one point to another, while being honest is a passage, more of a toward than a to. Where truth is a clear tour arriving inevitably at its end, honesty is a roaming. When you tell someone the truth, you give a provable, objective fact. When you’re honest with someone, you offer something of yourself in the process. There’s vulnerability in honesty, something carried out from the interior.

Both poems in this issue by Laux/Millar Poetry Prize-winners Allison Blevins (also a finalist for last issue’s Geri Digiorno Prize) and Joshua Davis demonstrate the honest messiness of loss, of grief’s complicated grace. In their prize-winning poem “The Fever’s Children,” we see in the loss of a father not sadness, exactly, but a set of feelings that are sharper, more dangerous and shifting. In “To our firsts,” a father’s shadow returns even over physical longing, and as readers we’re left considering whether any of our own desires can ever really complete themselves, whether some histories will ever stop haunting us.

Finalist Loisa Fenichell reaches similarly to describe the indescribable. “I want to touch the beginning of anything,” the speaker pleads in “Another Name for Weather,” a poem grappling with the beauty of a world capable of housing unnamable tragedy. “All out of voice,” Fenichell continues in “Touching,” “I jot down some notes that later, like a grief, I am unable to decipher.” And maybe that’s what grief is made of—its availability and shapelessness, how we’ll never truly know it though we’ll turn to face it again and again anyway like the poem’s shot bird, knowing already what we’ll find.

Aside from being our annual Laux & Millar Prize issue, this issue is particularly special for us—thanks to artist and musician Nora Kelly, for

the first time in our 12+ years, our pages also feature original illustrations that have been handmade for pieces within the issue. We’re excited to see our magazine continue to evolve with new elements like these, but we’re also excited to continue in more predictable ways: publishing more emotionally honest poetry, fiction, and art. ◆

Bryce Emley, co-editor

gregory djanikian

later years

Sometimes a sadness comes over me and I think a house with its dark roof and windows has entered our lives, and the wineglass elms have disappeared from the street of dreams.

I should not be leafing through our address book with the many crossed-out names, the pile of letters marked “undeliverable.”

I should not be imagining that the birthday lilies you brought me yesterday have already begun to droop.

Where is that photograph I love of us, or rather of our younger versions, sitting by a fountain in our summery selves, the water behind us arcing from a fish’s mouth as if the fish held a river inside it?

It’s been years since we’ve felt so inexhaustible. Still, there you are walking down the porch steps in your bathrobe to get the morning paper, even in snow, even on your one good knee.

It’s remarkable how we’ve come this far, your hands holding the news of the day as if we were part of it, the sun polishing the kitchen floor, the toaster tinging its bell.

1

I wish it could stay like this. I wish goodbye were an archaic word we could cross out without consequence, something left over from the old languages.

All the headlines have an ache to them. All the stories keep holding out for a better ending.

And here we are, having our breakfast cherries before all the trees have been sheared away. Here’s the honey I pass to you, love, honey made from a thousand bees tonguing a million flowers of sweet clover.

2 raleigh review

3 nora kelly

stephanie kaylor

[for years i believed...]

For years I believed that the mourning dove was named the morning dove, because I didn’t yet hear pain— only consistency, their persistence, before I learned how often these choirs are both the same.

4

In a corner of the backyard she buries fake silvers, half a dining set, pretending to have anything left, that they didn’t take the bones, even the bones.

Four empty chairs at the table; a single copper cup of water—

it has been there for two weeks or two months,

even the empty air declining to fill itself with this small offering. This devotion,

some fat fish flopping in the wildness’s claw, and then escape:

to learn to swim toward anything; to never know a route but the tides of away.

To pull away.

5 stephanie kaylor

memoriam

colin bailes telescope

It is after school hours, approaching dusk. My mother and I pass through the gate of our backyard to enter the school grounds, a hundred yards off the buildings refulgent in the growing dark.

I can just discern the glow of dimly lit hallways, see into the vague caverns of light so familiar during the day. Centered in the baseball diamond’s clay geometry is a ring of telescopes. We are guided by amateur astronomers to each one, each one increasing in aperture, magnitude. At the last, finderscope pointed at a blank emptiness, I press my eye to the black eyepiece—distances collapse, and an image of Saturn—planet tightly bound by rings—totals my field of vision.

When I lift my eye from the lens, the orange and yellow sphere lingers. For a few moments, it is the only shape I see.

6

book of parables

My mother gifts me clippings from her garden, takes a pair of scissors to the whole tangled mess—

Guiding me around the backyard, she shoves purple spiderwort, ruellia, devil’s-backbone, golden trumpet, shrimp and snake plant, blue porterweed into garbage bags for transport, cutting each stem below the root node.

When I get home, I plant them all directly into the earth, spread fresh soil and fertilizer.

After two weeks, most everything, except for the snake plant and purple spiderwort, has withered and died— the cuttings not properly propagated first in water to allow the ends to branch and root.

On the only bookshelf in my parents’ house, in the living room next to an outdated volume of photography and an encyclopedia of Greek statues, sits a Gutenberg facsimile. The hulking spine is white-leather bound, the crimson bookmark—a silk ribbon sewn directly into the binding— dangles like a tongue from underneath. Gilded fore-edges,

7 colin bailes

◆

gold letters engraved into the pillowed hardcover with a burin, the spine emblazoned in gold.

Inside, the ornate Blackletter cascades down the page, illuminated floral designs branching from serifs, connecting to Gothic images of disciples. ◆

I remember one of the churches to which my grandfather was appointed, a modest southern Methodist building,

wood-paneled sanctuary, slim windows of stained glass.

Laid between bars of lead—the Parable of the Sower, a lone tunicked figure, harvesting bag

slung over shoulder, an outstretched hand absentmindedly tossing seed. ◆

When my grandfather died, we cleared out the house and the shed, threw away entire boxes of Bibles,

all his sermons stuffed into desk drawers and folders—his tall handwriting

8 raleigh review

in red and blue ink sprawling across thousands of loose-leaf pages, impossible to read.

Over the phone, my brother is telling me about sinopia, how the fresco painters first applied an ochre outline to the plaster, a sketch from which to work, before starting on the final product.

He tells me that you can still see the red threads of pigment beneath the haloes of saints, remnants of error and fault before they were polished to perfection.

And I’m thinking of the brown anole I skewered as a boy, from mouth to asshole

with a twig, twining black intestines on a stick like some curious and tormenting god—

I was learning where I ended and the world began. ◆

All I see is a band of blue bordered on top by a lighter shade of blue

9 colin bailes

◆

◆

and hovering above a thin strip of ochre sand.

On the beach, tangled and clumped, dried stalks of sea oats—like bamboo, or the reeds of a pipe, only thinner, more brittle.

Behind me, a wall of sea grapes— and further inland, oleander and small plots of Norfolk Island Pine.

Ahead, the water flounces in fitful volleys—melting sandcastles children have built along shore.

My grandfather is sitting in his maroon recliner, taking out his teeth

for my amusement— the left canine and incisor

wired to a bicuspid. He laughs, smiling, displays a wide black void in the gate of his mouth. Every time we visit, he begins with the same imperative—Tell me a story. But I never do.

I am telling it now.

10 raleigh review

◆

john salter kilowatts

the writers and poets were in town for the annual conference. People like me were in ecstasy, drunk on literature, starstruck. Ellen Gilchrist winked at me after signing my copy of Victory Over Japan. Jay McInerny bought a round for all of us clustered around him at Whitey’s. At a party at John Little’s house, I spotted you bent over the gas stove, holding your hair back with one hand while you lit your cigarette on the blue flame. There were a thousand lighters in the house but you chose the burner, and that hooked me. I attempted some small talk that seemed that much smaller after being awash in brilliant discussion all week. You were the first woman I ever saw with a diamond stud in the side of her nose. After all, I was only twenty-one, and this was North Dakota, always late to every trend. Yes, it hurt, you said, but cocaine

11

helped. Cocaine! We remained in the kitchen, drinking wine. You were a former English major, though not a graduate, and liked to take in the conference every spring. An old drinking friend of John Little’s, like so many were. That’s cool, I said. Did you see my eye twitch when you told me you were thirty-three and married, with a baby? Your husband was in the Air Force, was a truck driver, was a secret agent, something like that, because all I heard was that he was gone a lot. Gone a lot. You were dressed in many layers, like some Victorian doll, a skirt with paisley tights underneath, a silk blouse over a tank top, tall brown boots that laced up. The more wine I drank, the more I wanted to peel you, to get at least halfway there before the night was over. John Little reeled in, found us inches apart, made a viewfinder with his fingers and took our picture. When he left the kitchen with a handful of limes, he shut off the light. I kissed you and after a bit, your reluctant lips softened. Whatever I had going on in my life, and I had a lot going on, seemed to be on a distant planet. A ride home? Yes, of course, and we slipped out the back door and climbed into my ancient Catalina, an environmental catastrophe but with enough room in the back seat for a heavy-breathed, almost desperate assignation. I’d been pulling current from that electrified air all week, and it arced and crackled like some Tesla experiment, right there on the ripped upholstery. We lay there for a bit, our bodies cooling in the spring air, not talking. Then we dressed and I noticed how long it took you, how methodically you arranged and straightened and buttoned and smoothed. You weren’t quite ready to go home, so we drove out to Highway Two and cruised west, listening to music, smoking cigarettes. I talked about the literature I was in love with, have you read any Cormac McCarthy, have you read any Raymond Carver, I talked about my own stories on hopeful submission to The Paris Review and Esquire, my plans for graduate school, my disdain for academia, my thoughts on extraterrestrial life when we saw a light that turned out to be a B-52 flying very low toward the Air Force base. You seized my hand and read my palm in the dashboard glow, following my lifeline with your fingernail. “You’re going to live a long time,” you said. What about my love line, I wanted to know. “You don’t seem to have one,” you said, and didn’t laugh when I laughed. You lived in a house only a few blocks from John Little’s, closer to the river, in a neighborhood that ten years later

12 raleigh review

would be razed by floodwaters. I want to call you, I said, because I did, I really did, this was delicious new territory, this was an Andre Dubus story. You nodded and wrote your number in the back cover of my Ellen Gilchrist book, where I would see it thirty years later while packing up my library after yet another divorce. I want you to know I gave pause, as the poets say, when I saw the number in your looping, feminine hand. I did call you a week after the conference was over, from a payphone at the Bronze Boot, where one of my sort-of girlfriends waited tables. You sounded reserved, even a little sad, and I wondered if the husband was in the background. Could I see you? Yes, you said. Could I pick you up tomorrow for lunch? That would be okay, you said. And I intended to, I truly did. But when I came around the corner and saw you on the porch, holding your baby across your chest, I rolled right on by, back into my lesser sins. I wish I could say it was some moral stand, but it was really just cowardice, my dear. You were wrong about my love line, though. I do have one, it’s just broken and hard to trace, and you might have seen that, had the light been better. ◆

13

salter

john

allison blevins & joshua davis finalist for the laux/millar poetry prize

to our firsts,

When I unbuttoned your shirt, I was a jewel thief, a mythmaker smearing red ink—dove’s blood— into flowered margins. When I said, Finish in my mouth, I meant: Love me. Please love me. I am shattered.

When I lifted my body to straddle your body, everything turned blue-red like a car chase siren. In that blurred and soft alarm, I learned words would always slice with sharper teeth. I put you inside me, thought about my father’s empty shoes like boats docked by our front door.

14

15 nora kelly

From the Sylvia Townsend Warner novel, Summer Will Show The night after my father’s body slid into its oven, / not at all like bread, / with none of its promise, // I wanted to make someone pregnant. / I wanted to trammel my father’s soul, if he had one, if anyone does / before it could escape. // We’re tightening locks, anointing doorways against plague. / I remember the nurse with her butterfly needle. / She stuck me three times. / Come on, little thingy. Please work . // Once I stood in a ring of seven-year-olds. / When I said, my dad has AIDS, / they scattered like starlings. // I long to write a line that rises / like a mangrove / out of water, into air unmoving, surrounded by black islands of mosquitoes / as dull light carves letters inside gaps between leaf and leaf shadow. // I long to write the line that slides clean / as the bloody knife you left in the sink, grandma, / cleaner even—sharp as the tip of a Spanish bayonet. winner of the laux/millar poetry prize

the fever's children

16

loisa fenichell

finalist for the laux/millar poetry prize

another name for weather

The moon shines, far too beautiful through this window— it’s incredible. There must be another word for it. Another sentence for oceans and mountains dissolve. Some nouns cannot grow in the concrete behind this apartment. In a small droplet of mind, I see it—a tapestry depicting specks of mountain, depicting desert, showing the two of us moving through an unkempt city. I want to touch

the beginning of anything, to make something that can be held. Instead, I tally the ways the pigeons shine, the ways you never eat your breakfast. Our stomachs are parcels of sky toppled over. I’ve told you about the nights I went to concerts alone, the days when all I could write was the name of the deli across the way—what does it matter? You leave. In the bath, I watch as the baby bleeds around my thighs.

17

finalist for the laux/millar poetry prize

Night chirps slowly, delayed and fragmented by the spring. All out of voice, I jot down some notes

that later, like a grief, I am unable to decipher. There’s the face

a sound can make, shrieking, after discovering that the dead bird’s body

still hangs from a thread attached to a tree’s dirty limb. I grew thirsty. I cried. Because the fog

was glistening, undermining my favorite season. My uncle was in the woods,

pointing, whispering, look, look. I did look. Hearing the shot was just too simple.

18 raleigh review touching

julia kolchinsky dasbach

the first letter at the beginning of the end

April 13, 2020

Dear L,

The tomatoes have gone bad in the bottom drawer and there are tornado warnings—I thought you’d like to know about my fridge. When my son asked for a scary story, I thought of all the frozen fruit that will not rot, so I told him, when I was his age on the Black Sea, I stuck my finger into a beached log and a wasp chased me down the Odesa sand and my hand swelled to a sun and it’s raining so hard here, L, like what I imagine our grandfather’s combat boots sounded like leaving, and there, my mother put a halved tomato on the sting because acid was the only thing we had to stop swell, and here, the baby just woke wailing and our street is flooding and I try to shut her mouth with my breast so her brother stays asleep as she wants and wants and not what I can give and I think, I have no ark but this ragged body that never learned to float. Still, she clings to its faults, its flaws and fallacies, unaware of all the ways its failing us. She doesn’t mind

19

the tomatoes, L, how our past keeps filling our children’s mouths. How do they not notice it’s gone so very bad? The day after Easter Sunday, nothing’s risen but fog, and a week after Passover, bread and the Red Sea stay unleavened in our people’s homes. Little did either testament know flood and sickness were just the beginning. My son acts out the plagues, becoming beast, lice, frog, and locusts, slamming his hands and trains on hardwood like boots and trains and this rain and the men he comes from who never came home. He throws heavy things at his sister, unafraid of death or hurt because what child of any history understands permanence. Parents always come back, they told him in school in another past when we could leave the house. How do you explain this to your children, L? Our air turned plague? Street turned river? Present turned strange past even our parents couldn’t have imagined. I wish I had your gift for jokes and baking, for beginning in laughter, so instead, I’ll try to end there, with my children, their bellies so full these days, faces the opposite of famine, laughing harder than this rain, L, I swear, laughing like there are no endings.

20 raleigh review

I guess that’s the punchline after all, I’m going to eat you like a tomato, my son says into his sister’s rising stomach and their laughter, L, so hard and full, it wakes the dead.

21

julia kolchinsky dasbach

caroline mccoy swept away

claire had rubbed the lace between her fingers, assessed its cheapness, before sliding the four-dollar-and-ninety-nine-cent thong inside the sleeve of her jacket. That was a mistake, lingering over the merchandise, pawing a pair of garish green underwear that she neither needs nor wants.

The usual assumptions will work in her favor. It goes without saying that she has five dollars to spare. Just look at her. Pale face free from all but the berry-hued lip balm she swiped from the grocery checkout aisle. Hair pin straight and glossy with a leave-in treatment she “forgot” to scan during her last trip to Walmart. She is dressed plainly, in jeans and an ivory-colored sweater. Her jacket is a crisp, gray wool. A woman like Claire wouldn’t be caught dead wearing this failing regional depart-

22

ment store’s tacky panties…. Or maybe it’s better to feign confusion, say she recently suffered a concussion and might she borrow the phone to call her husband because—well, look at that—she’s misplaced hers, along with her driver’s license and all identifying cards—credit, library, Costco, insurance, AAA.

She’s planning her defense while being herded about the store by an adolescent-looking security guard who has said nothing other than, “Please come with me, ma’am.” It seems that overnight Claire has transitioned from a miss to a ma’am, as if all of central North Carolina convened on the eve of her thirty-third birthday and decided that it was time to stop humoring her. The kid ushers her past cosmetics and through shoes toward a mirrored door at the rear of the store. The two-way glass isn’t fooling anybody. Beyond her reflection, she sees movement, the lurch of a shadow.

The door swings open and reveals a woman Claire takes to be a manager. She is trim, angular, and wearing a well-tailored suit. Her silvery hair is pulled tight against her scalp, accentuating the penciled peaks of her eyebrows and the burgundy pinch of her lips. She smells sweet with the kind of fragrance that appeals to both teenage girls and old ladies, but her appearance is sour. She does not seem like the kind of woman who yields easily to indignation, so Claire decides right then to proceed with polite bewilderment. She smiles expectantly at the woman, as if she is awaiting something as banal as directions.

The woman steps aside and motions for Claire and the security guard to enter. The room is dimly lit and cramped, with a metal filing cabinet, a narrow desk and rolling office chair, and rows of mounted shelves holding cleaning supplies and busted inventory affixed with round red stickers. Claire’s gaze rests on the desk and the boxy security monitor stationed there. It is blessedly outdated, flashing black-and-white images captured by poorly positioned cameras—the glass-topped corrals that populate the cosmetics section, a register abutting a dishware display, a sea of circular garment racks. Grainy customers and employees filter in and out of each shot, occasionally revealing their faces but more often only the crowns of their heads. The rent-a-cop who oversees this makeshift security station is still standing behind her, so Claire steps toward the woman and allows him to pass and take his seat in front of the glow-

23

caroline mccoy

ing screen. She senses that the woman’s eyes have remained fixed on her since she entered this room, so she meets them now and smiles again, conservatively, without teeth.

The woman appraises Claire. Stares at her, really, with an intensity that makes her cheeks grow hot, a sensation that is never not accompanied by an angry flush. As much as she’s tried to master the erudite poise of a professor’s wife, her nerves, her humiliations, her irritations always show up on her face, plain as day. Even this gloomy back room can’t hide them. The woman smirks. She seems pleased by the day’s turn of events, by the fact of Claire’s thievery and her red, red face; and, for a moment, Claire wonders if they’ve met before. She relaxes only slightly when the woman says the thing Claire has been counting on, the thing that always seems to exonerate her: “You don’t look like the shoplifting kind.”

the first thing Claire stole was somebody else’s husband. She was twenty-one, in her last year of college, and trained only in the biblical implications of adultery—that is, how it might impact her soul and no one else’s. Dan had mentioned his wife and two boys, and Claire knew their faces from the framed, four-by-six family photograph positioned at the corner of his desk. And yet she could not imagine them beyond the borders of that picture. In her mind, they lived only against a cheesy blue backdrop, three endlessly smiling concepts—Nadia, Jack, and Cooper.

At first, she tended her crush in juvenile ways, referring to Dan as “The Hot Englishman” among her friends and recounting to them the unremarkable things about him that she then found dreamy—the way the hair at the back of his neck curled with sweat by the end of each class, the way he lingered over every word when he read the Romantic poets aloud, the way he licked his index finger to turn a stuck page.

To Claire, Dan was exotic and wholly adult—much too adult to waste time with college girls—which is why she was surprised when his interest in her became unmistakable. He had invited her to his office to discuss her midterm paper, a bumbling argument that Shelley was a misogynist. How else could a man who abandoned his child and pregnant first wife, who tethered women like moons to his orbit, write with such self-satisfaction about ethics? She had pondered such questions over ten discursive pages. This was well before she had understood that all

24

raleigh review

that art-versus-artist talk drives Dan crazy. He considers it an American breed of discourse, subjective and irrelevant, as interesting as hearing about someone else’s dream. “Of course the art is better than the man,” he’d told Claire recently, when she reminded him that Picasso believed women were only good for worshipping or stepping on. “What would be the point otherwise!” But in his office so long ago, he offered no indication that he found Claire’s argument about Shelley as irritating as he must have. He only complimented her writing and recounted his own study at Oxford, how he had wept upon seeing the university’s marble memorial to the drowned poet. He had asked her, then, what moved her. No, he had asked her what turned her on. “Is there a work of art that inspires passion in you? Something that makes you want to weep or fuck?” he said. That his question made her uncomfortable felt to Claire like confirmation of her immaturity. She answered as best she could, by sidestepping Dan’s quest for some intimate piece of knowledge with a joke that now makes her cringe: “I cried over a Yeats poem once, but I think I was getting my period.”

They had been together for three months before she saw his wife in person. Nadia arrived at Dan’s office wearing gym shorts that showcased her lean, toned legs, and Claire realized immediately that she was beautiful. Her dark hair was pulled into an unruly ponytail. Her cheeks were full and glowing from whatever aerobic activity had occupied her morning. She knocked as she opened Dan’s office door and seemed startled to find him not alone but with a female student, Claire, sitting across from him. But as quickly as her jaw had clenched and her eyes had widened, Nadia’s pretty face relaxed and she smiled broadly. “I apologize for interrupting the scholars at work,” she said, addressing both Dan and Claire. Then, to Dan: “Your planner, love, and a little treat from Coop. He drew a picture for you but was too shy to show it to you himself.” She handed Dan a folded piece of yellow construction paper and the leatherbound calendar that, as far as Claire had been able to tell, never left his office.

Dan introduced Claire, then. He referred to her as his top student and told Nadia that the two of them had been discussing Claire’s complaints about the course syllabus. “Not enough women for this one’s taste,” he said, smiling first at Nadia and then at Claire.

25

caroline

mccoy

He was lying, of course. Claire had said nothing about the syllabus. In fact, she’d said very little at all that morning. She had awakened earlier than she would have liked to visit Dan at his request. Before Nadia had arrived, he’d done most of the talking, telling Claire about a waterfall near his mountain house and promising her that he would take her there very soon. The view from above, he’d said, was intoxicating, almost spiritual in its way of making you believe that green was the only color worth knowing and that forever was the depth of your perception. Even for Dan, it was early in the day for such effusiveness, but Claire pictured that view anyway, imagined herself at the slippery edge of a rushing stream. By the time she looked up to see Nadia in the doorway, she understood that he had orchestrated this meeting between wife and girlfriend, that he had guided the three of them to a precipice.

claire learned long ago that it was best not to correct other people’s assumptions about her. When she was in high school, her pastor father probably figured she didn’t drink or ride in cars driven by other teenagers or lie about where she went on Saturday nights. When she was the other woman, Nadia probably figured she was a mousy girl who couldn’t attract anyone as vain and self-important as Dan. And the first time, when she slipped a tube of mascara into her pocket, the cashier probably figured she was the kind of woman who paid for what she carried out of a store. Who was Claire to correct any of them? In many ways, she saw herself how they had seen her—as good and principled. Even the mascara had been a mistake.

She’d taken it after a fight with Dan about a paint color he’d selected and then despised. “Too blue,” was all he’d said when he walked into the bedroom, suitcase in hand, after spending his weekend at a conference two states away. The color was pretty, Claire thought. She even liked the name, “Swept Away.” It was the softest blue they’d considered, and Claire had cut the color further by blending three parts with one part white.

“You picked it,” Claire said to Dan’s back. He was sitting on the edge of the bed, untying the sneakers he’d originally bought for Cooper’s eighteenth birthday.

“If that’s true then I did so under duress. I thought the room was fine as it was.”

26

raleigh review

“What color was it?” Her voice came out tight and high. She hated crying in front of him.

Dan sighed. “You’re overreacting, Claire.”

“No, I’m not. What color was this room three days ago?”

“Oh, I don’t know, a whiteish color, something less repulsive than this.”

“Nope.”

She left him in their freshly painted bedroom, already spoiled in her mind. The walls had been a soft gray, not even slightly white or whiteish. She planned to show him photographs of the room before, to prove her point that he was being disagreeable—mean, even—despite having no real interest in their bedroom décor. She could have painted it without telling him, and he never would have noticed. She could have saved herself the trouble by not trying to involve Dan. That’s what she was thinking as she drove around town and while she wandered the aisles of her favorite discount store and, likely, when she tucked the mascara into her coat pocket. She was already in the store parking lot, having legitimately purchased a vegetable spiralizer and a set of hand weights, when she realized she’d taken the mascara by mistake. Standing beside her car, she dug around for her keys and found the slender cardboard box. It was one of those designer brands that had been marked down for the masses. The store’s tag advertised the original price and their price. Instinctively, she turned back toward the store, prepared to pay her eight dollars and ninety-nine cents. And then she just ... stopped. Holding the mascara in her hand, knowing that she’d walked out with it undetected, she felt an odd sense of relief. It was a calm and steadiness she had no idea she’d been missing until that moment. So she slid the mascara back into her pocket, returned to her car, and left.

That was six months ago. The bedroom remains “Swept Away,” and Dan has warmed to it. Or, he has stopped complaining about it. But there have been other fights and long silences and now the time away Dan is taking, the four-day weekend he’s spending at the mountain house. Claire can more or less match these incidents to the number of items stowed in the bottom drawer of her dresser and the cabinet below her bathroom sink. She has no occasion to wear or use half of what she takes. Not one thing cost more than twenty bucks. Most—like the stupid green thong she’s still concealing inside her jacket sleeve—were

caroline mccoy

27

cheaper. Not that taking inexpensive stuff is okay. But she’s not actually hurting anybody. No store will go under and nobody will lose their job because of her. At least there’s that.

Her father would say that this new habit speaks to her lack of integrity, some defect deep within her. She would die of shame if he knew of the chasm in her marriage, let alone her impulse to fill it with cheap underwear and beauty products. In her worst nightmare, he peers into her collection of neon and animal print, iridescent eye shadows and press-on tattoos, and says that she is not his daughter, that he has no idea who she is anymore. In the nightmare she cannot summon her voice to explain. But an explanation evades her conscious mind, too. All she knows is that taking these things makes her hate her husband—her life—a little less.

the stern-looking woman seems impatient for Claire to do or say something, to prove that she is or is not the shoplifting kind. Claire has always found it difficult to disappoint the person in front of her. It’s hard not to be whatever they seem to want or need. But she holds her ground and says nothing. She regrets obliging the uniformed kid who steered her here. What would he have done if she’d run or simply refused to cooperate? What would he do if she turned around right now and made a break for her car? He’d have to chase me, she thinks. Or call the real cops.

“Our cameras caught you stealing,” the woman says.

“I think you are mistaken,” Claire says. She is trying to project calm, coax the pigment from her cheeks.

“Carl saw you, too. He was watching you. Apparently he’s suspected you of stealing before.”

“Who is Carl?” Claire says, even though she already knows.

The woman gestures to the security guard. He raises a limp hand as if announcing himself present.

Claire nods in acknowledgement. “Nice to meet you,” she says, automatically. She underestimated this kid. This is only the third time she’s stolen from this store. Tried to steal. Technically the merchandise has not left the property.

The woman emits an annoyed grunt and motions for Carl to get on with something. He straightens himself and turns toward the security monitor, clicks an ancient computer mouse several times, and suddenly

28

raleigh review

Claire is watching herself on the screen. Despite the distant camera angle, she recognizes her own careful movements, the way one of her ears pokes out from a curtain of hair. Her head turns left and right and left again, mimicking the ingrained motion of a conscientious driver. Her arm reaches across an underwear display, hovers over a section for a beat too long. When it returns to her side, there is left on the table a small gap among the tight assortment of items.

“There!” the woman says. “Right there. You stole a pair of lacy underpants. Maybe more than one.”

Claire has Googled this scenario. What to do if you are caught shoplifting. She knows not to admit fault in writing. She also knows that she likely won’t be charged, if the people in this room even plan to call the police. She’s a white lady without a record. The item in question is caroline mccoy

29

negligible. The world is fucked in her favor. This has always been true, though Claire didn’t know it when she was young, when youth itself was another advantage she failed to recognize. That’s how Nadia must have seen things when she realized Dan was cheating with a twenty-oneyear-old—that Claire’s age was her advantage. Nadia has always been cool to her but not unkind. After Dan announced their engagement, she even invited Claire to lunch to discuss her integration into the boys’ lives, their soccer and band schedules, what they liked to eat, and the tricks they pulled to extend their bedtimes. Claire didn’t appreciate Nadia’s composure, then, her absolute fortitude and grace. She only felt burdened by her existence. Nadia was someone she wanted to impress and outshine.

There is no saving face now, no denying or excusing what Claire and the other two people in this room know she did. She reaches into her jacket sleeve, pulls out a wad of lime-colored lace, and extends it to the woman, who snaps her fingers around Claire’s wrist and begins to squeeze.

Claire gasps at the strength of the woman’s grip. “Hey,” she says, trying to tug herself free. “Let go of me!”

The security guard stands, seemingly dazed by the scene before him. “Lorraine, let her go,” he says.

The woman tightens her grasp and yanks Claire toward her. “I know what you are,” she says. Her slender fingers slacken, but her face remains hard. “Remember that next time you think about setting foot inside my store.” She lets go, but not before grabbing the pair of underwear from Claire’s palm.

Claire steps back and pulls her arms to her chest.

“Just leave,” Carl says. “We won’t call the police this time.” He remains standing before the security monitor, his eyes darting between Claire and the woman, who is smoothing her suit jacket and staring at the ground.

“See her out,” the woman says. “Escort her to the parking lot and make sure she goes.” Her voice is hollow. She sounds defeated, even though she is the clear victor in this embarrassing exchange.

The walk to Claire’s car feels endless. Long-legged Carl trips twice trying to pace her slow steps. People glance in their direction, but Claire trains her gaze on the store’s revolving door, on the brick pathway curv-

30

raleigh review

ing around the building, on the dusty hood of her dark-blue Honda. When she stops in front of her car, Carl does too. He’s waiting for her to go, like the woman instructed. Claire doesn’t have the energy to care what this kid thinks of her, but she is sorry—for stealing those other two times and trying to steal today, for that scene with his boss—and she says so. Sorry is a floodgate, and once she’s uttered the word, acknowledged her bad habit for what it is, she wants nothing more than to empty herself completely. “This isn’t who I’m supposed to be,” she says, but her words come out cracked and misshapen.

“It’s fine, ma’am,” he says.

He takes a step back, and Claire pulls herself together. She tells him, “My husband is having an affair.” She laughs when she says, “The woman he’s seeing is basically me twelve years ago.”

Carl nods knowingly. “My parents are divorced. It sucks.”

Claire has not said the word “divorce.” She’s barely let herself think in those terms—lawyers, assets, alimony. She can’t bring herself to imagine losing contact with the boys. She has no idea how she’ll earn any kind of living. She is in the middle of her Jesus Year and completely unskilled. She was an English major. Most of her friends—if she can call them that—belonged first to Dan. Her father is the only person she is sure would take her in. He’d be smug about it, but he would help. “Yeah,” she says to Carl.

“Lorraine shouldn’t have grabbed you like that,” he says. “She isn’t a bad person. She’s my aunt—my mom’s cousin, technically, but I call her my aunt. Her dad opened the first store in Charlotte like seventy years ago or something. That one’s barely hanging on, and she’s about to lose this one and the one in Raleigh.”

Loss itself defies Claire’s comprehension, but the messy grappling with it, the struggling against it—nothing makes more sense than that. She leaves Carl standing on the curb beside the building. She’ll do as the woman asked. She won’t return to this store. And a few months from now, when the building has been vacated and a For Lease banner has been draped across its prominent eastern wall, she’ll avoid driving by.

“meet me at nine,” Dan had said to Claire on the morning she and Nadia first laid eyes on each other. In the years since, Claire has wondered whether she and Dan would have married had he not piloted his first

31

caroline mccoy

marriage off that cliff. She’s wondered what the course of her life might have been had she not shown up to his office that day. He’d have moved on, she knows. If it hadn’t been Claire, it would have been a girl like her—quiet, admiring, eager to please. These very aspects of her nature are what makes a scenario in which she defied Dan, dumped him, never slept with him in the first place impossible. It would have taken an act of God to keep her from arriving at his office at eight fifty-five, jittery with specialness at having been beckoned by this man who seemed to adore her. And after Nadia became real to her, after Nadia knew and had filed for divorce, Claire turned almost militant about her own passion. She was unwilling to entertain the doubts and disappointment expressed by her father, let alone her own transient panic at the absolute certainty of it all—a marriage to a tenured professor, a ready-made family. Then and for much of her marriage, she believed she was loved and in love.

But this is the effect of her predicament: her whole life with Dan is now in question. Even what was good strikes her as an illusion. Their many giggling attempts at assembling toys and play structures for the boys (all of which Claire finished alone). Their dinner parties for Dan’s colleagues that always transformed into table-tennis tournaments (in which Claire, if she wasn’t clearing plates and cleaning the kitchen, played the part of spectator). Their lazy weekends and summers at the mountain house (which Dan spent mostly at his writing desk). In their decade of marriage, he has published four books and dedicated all of them to Claire with the same inscription: The winds of heaven mix forever. She was touched, at first, then perplexed. Had Dan forgotten that she hated Shelley? Certainly not. But the sliver of academe that engaged with Dan’s work might imagine that he and his wife shared a deep affection for the poet, and that was probably the point—to pad his public persona with some romance. By the fourth book, she had begun to resent the disingenuousness of the dedication. And now, she interprets it as a measure of Dan’s respect for her. What mattered to him was that he liked Shelley.

At home, away from the site of her humiliation, Claire can still feel the woman’s hand circling her wrist. She’d said, “I know what you are.” Not who but what, a thing, a thief. She walks from the foyer through the den and into the bedroom, hers alone while Dan is away—thinking,

32

raleigh review

he says, though Claire knows better. She assesses the cozy room, the king bed made fussy with oversized pillows, the matching marble-topped nightstands, the chaise that no one ever lounges in, the abstract beach scene they felt pressured to purchase at an art show. In terms of property, she brought little into the marriage, no furniture and not any real money compared to Dan’s own inheritance. She had a ring that once belonged to her mother and that she has since lost. It was a plain gold band set with an opal that Claire loved to watch glimmer multicolored on her finger. She had some knick-knacks from her childhood home, the sixpiece silverplate flatware that had belonged to a grandmother she’d never met, and a sizeable collection of books. Those things are mixed in with everything else—Dan’s possessions, gifts he’s given her, furnishings and photographs and souvenirs they’ve accumulated together, all the stuff that no longer feels like hers.

Claire spins loose her wedding ring as she walks to her dresser. She opens her jewelry box and places the ring in its usual, prominent spot. Her hand lingers over the collection of jewelry, grazes the smooth garnet beads Dan picked out at an estate sale one summer and the velvet case that contains a set of pearl earrings he gave her on her twenty-eighth birthday. She fingers a small emerald pendant and its tangled gold chain. The stone came from one of her mother-in-law’s gaudy dinner rings, which the family dog ate and expelled without damaging anything but that single emerald. Her mother-in-law had the stone recut and made into the necklace for Claire. Dan has always found its provenance hilarious, and Claire occasionally wears it to make him laugh. She disturbs a stack of bangles brought back from an anniversary trip to Peru, finds beneath it a Timex still ticking on a cracked leather band. It’s not valuable or memorable, just a relic from whenever she last found it necessary to wear the time on her wrist. She returns the watch to its place and looks again at her wedding ring. It’s worth more than everything else combined. The oval diamond sticks up too high and snags her sweaters, but Dan chose it so she has loved it. Her naked hand hovers over the ring for a moment, before she closes the box and steps away. ◆

caroline mccoy

33

katherine joshi burning

driving home to dc on a late Sunday afternoon, Diana and Mark passed a truck burning on the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

The truck was in the northbound lanes, perpendicular to the bridge. The sides of the truck were already illegible, black with smoke. The fire rushed toward the sky in great plumes, bright orange giving way to puffy black clouds, thick and impenetrable. Diana imagined what it would be like to walk through such a cloud, to experience the sensation of sudden blindness, smoke pressing into your eyes and ears and nostrils until the cloud absorbed you, becoming part of the fire. She leaned forward until her seatbelt caught, trying to wrap her mind around what she was seeing—the impossibly tall flames, the heat radiating in the air, visible against the still bright sky, the line of cars paused dangerously close, held

34

back by an invisible barrier. Diana was considering the combined effort it must have taken to convince that much traffic to stop, when Mark reached from the driver’s side and pushed her toward the seat, her back slamming against the worn leather.

“That’s distracting.” Mark said this, as he did many things directed at Diana, out of the corner of his mouth. He always gave the impression that speaking to Diana was painful, forced. It was not unlike Mark to believe Diana was the distraction and not, in this case, the enormous

katherine joshi

35

clouds of smoke curling around the tops of the bridge, disappearing the green iron. She knew he was watching the fire as well, the truck now directly opposite them. Diana crossed her arms and rolled her eyes, and immediately felt flustered at her own actions. Before, she never would have dared to show her irritation so blatantly. Before, she had been consumed with being the good wife, but she also thought she had been in a loving marriage, so she had her reasons. They passed the truck and Diana turned around in her seat, consumed by the fire, watching in fascination as the flames turned even more orange, the smoke above impossibly thick. A deep smudge on an otherwise flawless sky.

back home, Diana did her due diligence of helping Mark carry in the bags before escaping to the bathroom to look up the truck fire. A short article posted on WTOP provided minimal information—the fire was due to a car failure, not malicious intent. How odd our times are that the article had to provide such a clarification, Diana thought. The only other information the article provided was on the traffic delays, on a fire truck entering against traffic in order to reach the burning vehicle. She perched on the closed toilet seat and considered what this must look like, fire and smoke meeting the great gush of water, practically hearing the sizzle of extinguished flames.

Mark yelled her name from the bedroom, upstairs. She didn’t have to see him to know he was unpacking, her still-closed suitcase already a nuisance to him.

They had gone away for the weekend to a couples retreat in Connecticut. The website promised in-depth couples counseling, free of the normal stresses of everyday life. It also promised a rekindling of romance, a reckoning of any foundational issues within the relationship—specifically, the ones buried deep below or that you were not even aware you had. The website guaranteed that couples would leave the retreat feeling renewed, refreshed, and more committed to their relationship than ever before. Diana was more exhausted than she had been before they left and felt exactly the same toward Mark, if not even slightly more irritable. When he first suggested the couples retreat, she had been on board with the idea. Maybe the retreat would mend what had been brewing between them for years; maybe it would convince

raleigh review 36

Mark he was still in love with her, although all signs pointed to the exact opposite. Maybe the retreat would give Diana the permission to excuse herself from the marriage, slipping out a side door after gaining proof that she did her level best to save the marriage—she had agreed to the couples retreat, after all. At different points throughout the weekend, her reasoning changed. The few times Mark smiled in her direction, it became easier to convince herself that she had been overreacting these last two years; reading into actions and gestures that were innocent and not directed toward her. But when Mark grabbed her by the wrist during breakfast Sunday morning and took her to a corner of the room, believing she had been particularly aloof to an older couple from Queens, she could not help but feel that she was being placed in time out by her very own husband. Diana had simply told the man from Queens that she had never had whitefish. But now, Mark’s tight grip on her shoulder erased any kind smile he had thrown her way, reducing Diana to pieces for allowing smiles to convince her everything was fine. She could no longer deny the truth, as much as she wanted to: a couples retreat would not mend their relationship problems, because those issues were buried so far beneath the surface they would likely never be uncovered.

It wasn’t that either of them had cheated or anything. Their families got along well. The two did all the things you would expect of a childless married couple in their thirties: weekend dates, happy hours with friends, outings appropriate with the season. Diana had hiked more times in her life than any sane person needed to. And even though Diana was pretty sure she knew why her marriage was an unhappy one, she still found the whole idea hard to stomach. Not the couples retreat by itself, but the fact that she was nine years into a marriage that had been throwing red flags at her from the very beginning, red flags that she hadn’t picked up on until a couple of years ago, so late into the marriage that Diana was too embarrassed to admit her ignorance up until that point. When had she become a person who closed herself off in their miniscule guest bathroom to do something as innocuous as reading an article on her phone? When had she become an inactive participant in her own life, constantly placing her husband’s desires—and thoughts, and opinions, and goals, and approach to life in general—above her own? When had she become so content with being unhappy? Diana couldn’t deny that

katherine joshi

37

she had fallen a little less in love with Mark since their marriage. But when had she tricked herself into believing that was an acceptable way to live the rest of her life?

she had been very in love with Mark in the beginning. They met as sophomores in college, and he would bring her banana laffy taffy and stay up all night helping her cram for exams and take her out for real dinners, at restaurants with tablecloths and martinis. Diana was young enough to still think love was a simple act, marriage an agreement you couldn’t back out of. She was idealistic. She watched each of her uncles divorce and remarry and assured herself that would never be her; they had made the wrong decisions. Judged the union incorrectly. She wouldn’t make the same mistakes. To her, marriage was like a math equation; maybe you put a few wrong answers down along the way, but eventually you arrived at the right answer. When she met Mark, she became quickly convinced that the boy who broke up with her by leaving a note on her car the first day of senior year in high school, or the other one who hid in the kitchen while his mom passed on the bad news, or all the other ones before had been the wrong answers. With Mark, she solved the equation.

It wasn’t until she sliced her hand open while pumpkin carving at her brother’s house that she realized something was off. They were seven years into the marriage at that point. Her brother, David, ushered her inside, instructing her to hold her hand up while he located the bandages and Neosporin. “You look like mom,” she remembered observing, then laughing at her own comment, David smirking briefly while he rummaged underneath the kitchen sink. Eventually his boyfriend Thomas emerged from the upstairs bathroom with the first aid kit, yelling about how David did this each time there was an injury, frantically searching the kitchen while Thomas calmly went upstairs to retrieve the kit. They stood on either side of her in their kitchen, taking turns as they bandaged the wound: David cleaning it, Thomas drying it, David applying Neosporin, Thomas wrapping the bandage, reminding her to keep her hand upright. She felt the warmth radiating off the two of them, the undeniable fact that they were a team, a properly solved math equation. She felt almost embarrassed that she had caught herself in the middle of their connection, nearly apologized for that instead of apologizing for bleeding all over their kitchen floor.

raleigh review 38

“No, no, don’t worry, you’re fine.” Thomas squeezed her shoulder when he said this, and Diana smiled, and it was the warmth of the squeeze, and the selflessness of the smile that made Diana suddenly envious. As she went to rejoin Mark and her brother’s other friends in the backyard, she found herself wanting to scream at her husband, why didn’t you come in and help me? But he instead was engrossed in a conversation with one of David’s friends from work, and it was only when she sat back down next to him, her chair scraping slightly against his, that he glanced harshly in her direction, muttering “are you done?” and then quickly “are you okay?” And before, Diana would have treated this as a slip of the tongue, but she now somehow immediately knew that it wasn’t, that he had intended to say the first phrase. She furrowed her eyebrows and tried to understand what was happening, to navigate the peculiar situation she had suddenly found herself in.

Here’s the thing about pumpkin carving when you have a hand injury: it proved remarkably useful to take stock of everything else going on. Since Mark was now in charge of carving their Stranger Things pumpkin (an idea she had earlier been excited about; now, she thought “how fucking original”), Diana drank her wine and tuned out the conversations and focused on the faces of everyone around her. And she noticed how Mark would smile his best fraternity president smile while he talked to David’s co-worker, but that it stiffened anytime he turned toward Diana, and that each time he gave her his stiff smile, David would leer at Mark, so quickly it was easy to miss, so quick that Diana wondered how many times she had missed it before. She noticed that David and Thomas were the only ones not to laugh whenever Mark shared something he believed humorous, and that Mark was the only one not to laugh when Diana tried to crack a joke, and she knew that couldn’t be coincidental. When they were done carving, and Diana gasped and commented on how good her brother’s Great British Bake Off pumpkin was, Mark seemed to choke down a scoff, before suggesting they share the pumpkins on Instagram to find out who others thought was the winner. David rolled his eyes at this suggestion, to which Mark said, “no, no, it will be fun! I’m sure yours will win!” But the practically murderous look in his eyes implied that he did not want to do this out of fun, and that he would react poorly if, in fact, David’s pumpkin did win, and Diana thought pumpkins, really? She was never sure if the thought was a

katherine joshi

39

reaction to Mark’s childish resistance to losing, or his determination to be the best even in trivial things, or if it was at herself for having to slice her hand open while pumpkin carving to realize something was seriously off with Mark, seriously off with her marriage.

David and Thomas went inside to get the Halloween-themed cupcakes and Diana slipped in quietly behind them to use the bathroom. They must not have seen her because she stared at herself in the mirror while listening to them whisper about how insufferable Mark was. How they were unsure how Diana put up with him; why she didn’t get out while she could. “I mean, she’s thirty-one,” Thomas whispered. “Still plenty of time to meet someone else and start fresh.” Start fresh? Diana stared at her almond-shaped eyes so long she eventually couldn’t tell which version of herself was doing the staring: the real self or the mirror self. David, who was a groomsman in their wedding, who let Diana carry him around like he was a pet cat when they were children, who followed Diana to DC, didn’t object to Thomas’s thinking. Instead, he agreed. He said he would help her, even.

They didn’t stay for much longer, Diana practically swallowing a cupcake whole, Mark glaring at her until she realized she had frosting on her cheeks, and she wiped it off, quickly, before returning her gaze to Mark, who was chatting to the co-worker, again. Diana wanted to scream. What, are you recruiting him? Are you trying to get him to fall in love? Their pumpkins all now sat in a corner of the patio and the longer Diana looked at them, the more menacing they became, the more she wanted to raise a foot high and smash them all to pieces.

David and Thomas gave her long hugs as they left, and she joked, “What, are we not seeing each other again?” They laughed, but the sickly feeling in her stomach told her she knew why they were hugging her extra long. How many other times had she received an equivalently long hug without realizing it?

Growing up, her father always teased her for being the last one in on a joke. “It just takes you longer to put it together, that’s all,” he would say, squeezing her shoulders. “But that’s what makes you you. It just takes you a few minutes to put the pieces together.” Leaving her brother’s house that night, she wondered how long she had not been in on the joke. How long had David and Thomas leered at Mark? How long had Mark acted

raleigh review 40

as if every single move of Diana’s was a personal embarrassment to him? In their twelve years as a couple, how much had she missed?

diana told one person the truth of their weekend getaway, and when Prisha asked how the couples retreat was, Diana pushed aside the therapy sessions and early morning yoga and tower of muffins and instead told her about the burning truck. When Prisha expressed shock, having not seen anything on the news, Diana Googled the incident on her work computer, turning its screen toward Prisha, who peered over the top of her cubicle to read the article, her mouth gaping at the pictures.

She and Prisha had started working at Girls First at the same time four years prior, a nonprofit that promoted female empowerment in local public schools. Diana soon realized that it was very easy to describe what the organization did, but hard to actually put ideas into action. There was always a parent who disagreed with their message—haven’t we already shown girls they can be whatever they want to be?—or who didn’t see the value in educating young students on things such as sexual violence and abusive relationships and how to advocate for yourself in the workforce. The conundrum was simple enough to work around: the idea that middle schoolers were too young for these messages, yet high schoolers had already received this information. Their director spent chunks of her day calmly explaining that we couldn’t assume high schoolers were receiving these messages from their parents, that the label change from middle to high schooler didn’t mean the girls were any less naïve. She was an astute woman in her early forties who wore pink blazers purposefully to confuse any male executives she had to go to battle with. Diana had read about the organization in the Washingtonian and applied on a whim; she went from teaching high school students to crafting lesson plans on things like “Being your Boldest Self.”

Diana shared the truth of her weekend with Prisha because she was the person she spent most of her time with, even more than her husband. The sad, accepted truth of desk jobs in the twenty-first century. If Prisha had a lighter sense of humor, Diana would joke that Prisha was her “work wife.” But Prisha, by default, was stern, hardened by years of correcting colleagues who added an extra syllable to her name, no matter how long they worked together; by dates that insisted on asking

katherine joshi

41

where she was “really from,” only for her to tell them she grew up in Philadelphia. Prisha had met Mark a handful of times, and, at their most recent work happy hour, Mark became obsessive at making Prisha laugh over a string of stories about his uncle that Diana had heard countless times. It wasn’t until he was on his third drink that he realized Diana had moved to the other side of the bar, half listening to another coworker complain about her dog’s recent trip to the groomer. He held Diana’s elbow tightly as they walked home, only waiting until they were inside their house to unleash how embarrassing it was for him to be left alone talking to Prisha. Diana, slightly buzzed from several gin & tonics, asked “Embarrassing for who?” before making her way upstairs. Knowing it would irk him, she dropped her purse on the bottom step. A second self had made its presence known after the pumpkin carving and when it showed up in moments like this—acting out through small, petty gestures, rather than taking a sledgehammer to their entire relationship to see what was salvageable—Diana knew the second self had been waiting for her attention for a very long time.

When she first told Prisha about the retreat, she hadn’t said what her mother would have if she had told her—“Good for you, commitment is so important”—before yelling at her father that she wasn’t going to show him where the TV remote was one more goddamned time. Instead, she asked if Diana had ever thought about leaving him.

The question was simple, and Prisha’s gaze on hers implied that, somewhere within those casual happy hours with Mark, she picked up on what everyone else had all along but had never bothered to mention to Diana. But unlike her family, who apparently decided long ago that stuffing the truth deep inside was the kindest option, Prisha decided to lay the truth out, where Diana could no longer hide from it. In years prior, she would have laughed in Prisha’s face, would have told her she was being ridiculous, would have blown up in anger. But now, the wiser self couldn’t pretend to be surprised at the question, even though she wanted to, and she coughed nervously instead of answering, the whole interaction leaving Diana feeling sticky and doubtful.

Looking at the fire photos with Prisha—the fire that she could still see burning inside of her—Diana felt that same sticky feeling return, a vastness opening. She could practically feel the rocks breaking loose and

raleigh review 42

tumbling away underneath her feet, the valley of air patiently waiting to grab her tightly and suck her into the depths below.

the truck fire was distraction enough that Prisha didn’t press Diana for more information on the couples retreat until mid-afternoon, when they were huddled next to the coffee station. Many of their Girls First lesson plans emphasized reflection as a way to spark growth. In her past life as a teacher, she had made the same speech to her students countless times but often found herself struggling to abide by the practice. She had barely reflected on the weekend at all. She was instead wondering how often cars caught on fire. To satiate her friend’s questioning, she murmured, “It was fine. Didn’t fix everything but we learned a lot,” and turned to walk her coffee back to her desk, wondering how much longer she could maintain the lie.

that night, however, a memory of the weekend shook itself loose and suddenly Diana was consumed by it, opening her eyes against the dark bedroom, shifting from almost asleep to fully awake at dizzying speed. Mark was snoring next to her, and she realized the snoring itself was what caused the memory to dislodge.

Late Saturday night, Diana had found Mark’s snoring unbearable and grabbed her cell phone and went for a walk.

The couples retreat was at a stately bed & breakfast near Woodbury, a place that looked prepared to host dignitaries and ambassadors and not slouching couples hoping to avoid divorce. Diana was glad to find no one at the front desk and greeted the nighttime air greedily, the day’s heat still thick in the air.

The spa and pool buildings, the tennis court, and the mass of cars quickly gave way to a thick, densely packed forest. They had walked through part of it earlier that day during a group therapy session, and Diana believed she could still hear the twigs and leaves crunching beneath their feet as they walked in an obedient single line, observing the therapist’s instruction to remain “silent and observe.” And Diana had observed, not because she particularly wanted to, but because she had always been good at following instructions. She thought of how her mother often picked early spring flowers before they died in the next

katherine joshi

43

freeze, once getting cursed out by a stranger who didn’t understand her intention. She was only trying to preserve their beauty before the late stages of winter gobbled them up again. Diana considered breaking the silence to share this story, Mark’s imagined response filling her with a strange sort of glee. It was hard for her to imagine that Mark was truly trying to improve their relationship to ensure they were both happy; she couldn’t shake the feeling that the decision to attend a couples retreat was good only for appearances. That Mark only cared about what the outcomes would show others. At his core, he was still the fraternity president, trying to ensure a shiny surface while the inside slowly rotted.

She should have asked him, during the therapy session, “Am I still just an accomplishment, a trophy for you to shine and bring out on special occasions? Did you forget to break up with me after college, after I could no longer serve you and your fraternity’s image as the impressive scholarship student and now you’ve found yourself years deep into a marriage, unsure what to do next?” Because even though she had dropped the role of “president’s girlfriend” long ago, he still considered himself a president, of sorts, with all the expectations that came with the title.

She followed the curve of the road, which dipped to the left. The lights of the B&B were suddenly extinguished, the line of trees consuming her in the darkness. Diana felt her heart quicken but she wasn’t afraid. The moon was out, and she knocked her head back to take in the stars. She relished the absence of people, the absence of voices, the countless stars that she so rarely saw in the city, greeting each one like an old acquaintance.

A twig snapped, and Diana kept walking with her head knocked back, assured in her footing on the smooth road. She did not wonder if Mark had woken up or worry about his reaction if he had. She let the heat glide over her like a new layer of skin, luxuriously bathing in the sickly stickiness, and it was only when she heard another twig snap, this time closer, that she looked straight again, already knowing that she was no longer alone.

The new presence was invisible in the dark, but nonetheless perceptible. Diana could hear it moving slowly in the nighttime air, imagining the heat parting around it like an endless curtain. Her heart started to race. She remembered an article on why rapists target runners, back

raleigh review 44

when she used to be a jogger herself; the ponytails were easy to yank. She touched her own ponytail, her dark hair frizzy from the humidity. Fumbling, she turned on her phone’s flashlight and moved in a darting circle, hoping to catch the predator before he caught her.

When she finally saw the eyes, she had already accepted her fate. But the longer she looked, creeping slowly backwards, she realized the eyes were much lower to the ground, wide and yellow. They were unmoving and detached from whatever they belonged to and, for a moment, she stopped, thinking if she concentrated long enough that she would be able to make out the rest of the body; make out the thing that was waiting to kill her. She considered moving close enough so that the flashlight consumed the darkness, rather than the other way around, in order to bring the body into full exposure. The eyes were practically sparkling from the light and Diana’s breathing momentarily slowed, utterly mesmerized. But then whatever it was took one silent step forward, the eyes increasing in size, and she stumbled before jogging back toward the B&B, occasionally checking behind her to find the creature had not moved, was not moving, and she greeted the lights and electrical hum of the inn with a great, heaving sigh, practically shaking when she finally reached the front doors.

The B&B was silent, not a soul in sight, and Diana was momentarily consumed with the belief that she had stepped into some alternate dimension, left alone to survive on her own devices. This wasn’t a new idea of hers; ever since reading an article on mysterious disappearances in national parks, she was overcome with the conviction that that very thing was going to happen to her one day. That she would lose sight of any hiking partners and emerge to find herself somewhere else entirely, forever separated from those she knew. Plucked away into someone else’s world. Sometimes she didn’t think that would be too bad. Maybe the other Mark in the new dimension wouldn’t be so high strung.

But tonight she reached for something familiar, in order to help her organize her thoughts. She sighed with relief when she reached the room and opened the door to Mark’s snoring.

She locked the door and slid down to sitting, holding her forehead in her hands. She couldn’t quite grasp what she was feeling. It was something greater than fear—a concept that, by its nature, signified

katherine joshi

45

conformity. She often found herself unafraid of things others feared the most, firm in her belief that what people really feared was not the actual thing itself, but the unknown. And now, as she caught her breath and relived the encounter, she was not afraid of whatever she had seen. Something else was growing inside of her; the unsettling feeling that she had come face to face with not her death, but her equal. Herself in another form. She closed her eyes and imagined she could hear it moving slowly through the hallway, waiting until it sensed her on the other side.

She never told Mark, knowing that he would focus instead on her leaving the room late at night and how that would look to others. She knew he would find some way to write off what she had seen; that it was probably a raccoon, or an opossum, or even a deer, but Diana knew the creature was none of those things. She wouldn’t have been surprised to discover it was an entirely new species, something unnamable. Something that did not yet clearly signal fear or curiosity or innocence.

Their row house was quiet. The street was, for once, quiet. She slipped out of bed and slowly rolled up their shades, taking in the street below. The neat line of cars, trees thick with leaves. The hair on her arms prickled, and she imagined any number of places the animal, if it was indeed an animal, could be at this very moment. Alone in its Connecticut forest; hidden away in a pack; walking down her city street; waiting on the other side of her bedroom door. Quietly breathing, ready for the inevitable.

when diana brought mark to meet her parents for the first time, the first thing her mother said to her when they were alone was: “He sure smiles a lot, doesn’t he?”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

Her mother held her hands up, defensive. “I’m just pointing it out, it’s a lot of smiling. Who needs to smile that much? You can’t even tell what he’s thinking from all that smiling.”

“He’s probably just nervous.”

Diana’s mother looked shocked at this, her mouth gaping open. “What’s he have to be nervous about? We’re the ones who should be nervous.” They were in the kitchen preparing coffee, Mark and Diana’s father in the living room. Diana could hear Mark laughing and wondered

raleigh review 46

what her father thought about another man laughing so much and so purposefully. Her brother, still in high school, had politely shaken Mark’s hand before darting down the back stairs to meet friends. Everyone was civil. Everyone was polite, talkative, some more than others, sure. And was it so hard to believe that Mark was nervous?

Diana’s mother pulled out a tin of wedding cookies and, even though she loved them—and knew Mark would love to hear the story of how her father squirreled some away for himself each time a new batch appeared—she felt a twinge of embarrassment, thinking of the elaborate dessert Mark’s family had provided when she met them for the first time. A delicately decorated chocolate cake, Diana dropping some of the dark frosting on the new dress Mark had bought her for the occasion. At first, she had found the gift thrilling, the very idea that a boy wanted to buy something so nice for her, but now, as she looked around her parents’ crowded, dated kitchen, she considered that the dress might have been more than just a nice gesture. He was from a tight-knit, waspy Connecticut family; her parents, both from sprawling Italian families, had grown up next to each other in Cambridge, in thin row houses that had been in their families for decades. Didn’t that bring its own kind of status, its own kind of wealth? They were both born and raised in New England, but might as well have been worlds apart, for the way Mark referenced their childhoods.