ABOUT RAGE

RAGE is a global multidisciplinary feminist zine and platform—both print and digital—for expressing feminist rage as a force for creative change and collective action.

Non-profit and inclusive, the platform is a space where rage can be unleashed with vulnerability and dignity. We publish bold, experimental feminist work—writing, art, and more—primarily in English, with an emphasis on multidisciplinarity, harnessing feminist rage as the powerful source of creativity it can be.

Beyond the page, we also host creative feminist workshops, events and panels that amplify and platform feminist voices and themes that are too often unheard.

The project is led by the RAGE Collective: a group of feminist artists, writers, academics, creatives, and activists, based around the world, but primarily headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Charlotte Rohde

EDITOR ’S NOTE

JUNE 2025

In this second volume of RAGE Zine, almost 50 artists, writers and activists from over 20 different countries across the globe have been gathered to unleash feminist rage in their rawest, most unfiltered and electrifying forms. Featuring poems, paintings, essays, illustrations, collages, digital art, photography, film stills, hybrid experiments and more, the zine seeks to showcase the many faces and manifestations of rage in a feminist context.

From body horror to digital dissent, from acts of quiet resistance to visceral eruptions of pain and power, this volume is angrier, bolder, and more unruly.

From Myfawny and Arianell’s interactive piece about DIY activism, to Prantip’s beautiful collages, and Anastasia’s article about bringing justice to Greenlandic Inuit women—this volume brings together a mosaic of rage’s many expressions, each piece demonstrating how feminist rage is felt in all spheres of our lives, and how we can creatively do justice to the profound value of this complex emotion.

We have grown, not just in numbers, but in urgency, in depth, and in intensity. And the rage has grown with us. We are publishing this volume in a moment of intensified backlash against the most basic of our rights. The global rise of authoritarianism and fascism is deeply gendered and racialised; discriminatory rhetoric against migrants and trans people is increasingly normalised in mainstream politics; reproductive rights are being questioned and dismantled with cruelty disguised as law; and across the world, from Gaza to Sudan, conflicts, violence and humanitarian catastrophes continue with impunity, with women, LGBTQ+ people, and marginalised communities bearing the brunt.

There is much to rage about. And this rage is a necessity for change, for rallying our collective power, fuelling the flames of this project.

RAGE Zine is a space to provoke, a platform for experimentation and release. A space to transmute anger into form, into language, into something that moves, that creates friction. Featuring a range of voices confronting and igniting political and personal wounds—there is room to be devastated, erotic, grotesque, furious, undone, torn, yearning. The zine is a vulnerable space, with room to express and examine the full scope of our rage and our feelings through a feminist lens.

We are not advocating for the aestheticisation of rage, or for the palatable transformation of rage into consumable cultural, artistic or literary products. Instead, we want to encourage channelling and harnessing rage as a force for creativity which can, in turn, transform the world around us.

We are not asking for permission. Our rage is a necessity and a right. We hope that RAGE Zine can be an antidote to the systematic repression of our rage. May our rage change the fucking world.

love & rage, The RAGE Collective

RAGE RESEARCH continues/d by Roselil Aalund

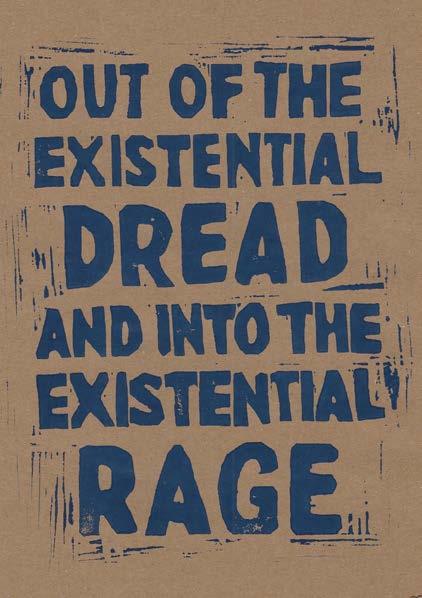

Existential Rage by Erica Engdahl

SOMEONE COME AND KISS MY RAGE by Farah Bejdadi

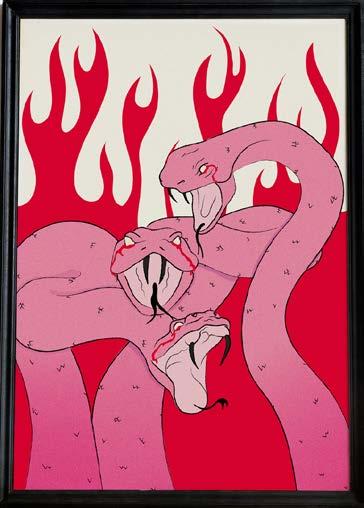

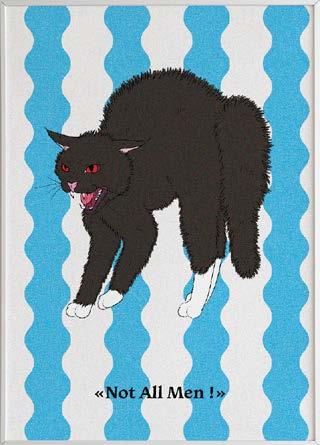

Mauvaises Victimes + Not All Men + Get Out of My Face by Troty

They’re Killing Us But No One Will Hear Us Scream by Arielle Rose Khosla

I fill my mouth with female rage by Julia Marie

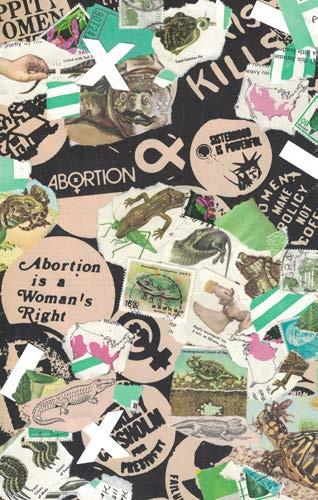

A Woman’s Right by Liz Walker

RAGING VOICES From Post-Election USA by Mathilde Betant-Rasmussen

Still Angry by Emily Bisgaard

Q&A with Caroline Motley, Movement 4 Choice

Founder by RAGE Zine

Rage Is Where We Begin by Keni Nooner

Essays on Reaction Drop I: Rage, When I didn’t have the strength to react by Mädchen Vivi

Stickers and Markers by Myfawny & Arianell Boudry

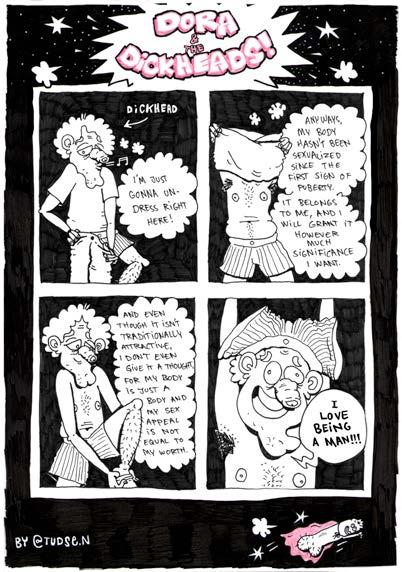

Dora & the Dickheads by Tudse

Lady Bluebeard by Cally Lim

Girl, so insane by Laura Griss & Mike Haas

Maria Labo by Dan Aries

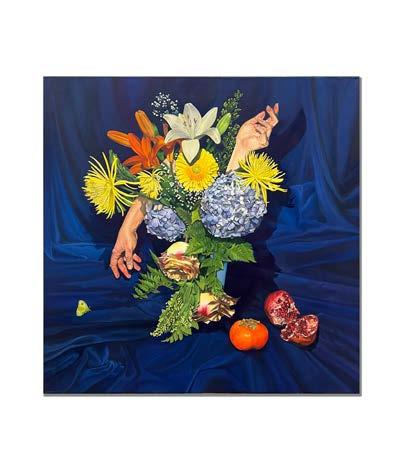

Woman as Object: Bouquet + Woman as Object: Figs by Juliana Stankiewicz

AFFECTIVE (T)ERROR: Hysteria as a Feminist Dialectic of Rage by Nadia Razali

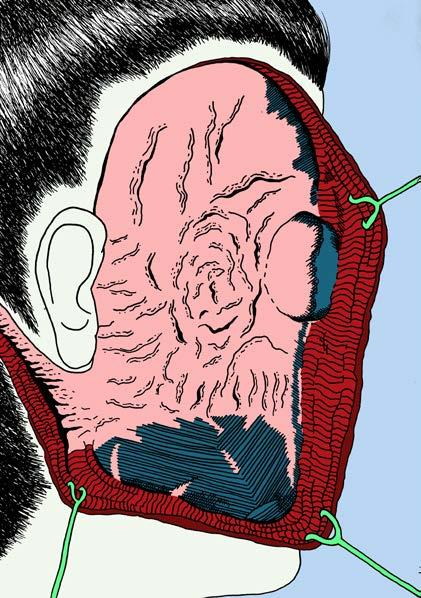

Beauty at any cost by Stefanie Lechthaler

[Short] feminist poem on sex by Myrto Apostolidou

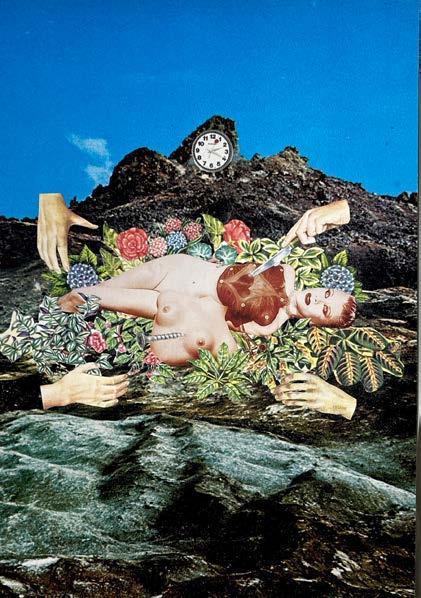

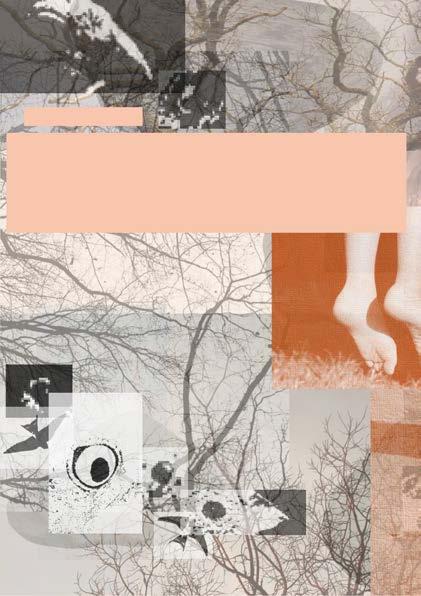

Untitled collages by Prantip

24 Hour Snuff Pornography £10.99 A Month by Hannah Corsini

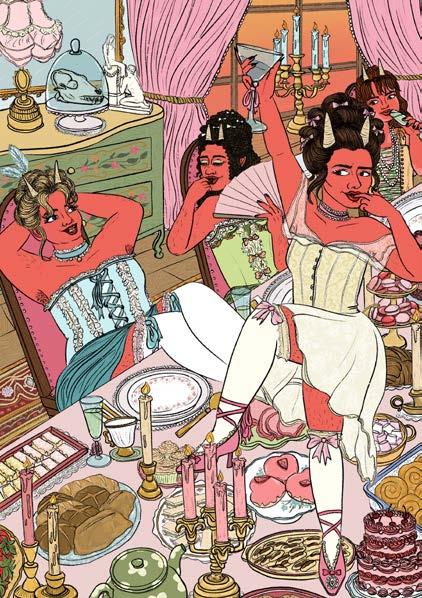

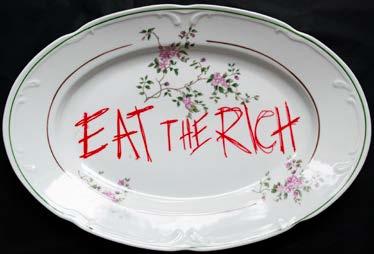

Let Them Eat Cake by AJ Duncan

Summoning Vultures by Annika Hyeonjin Julien

The Screaming Disease by Veruschka Haas

She’s leaving home by Mathilde Clear

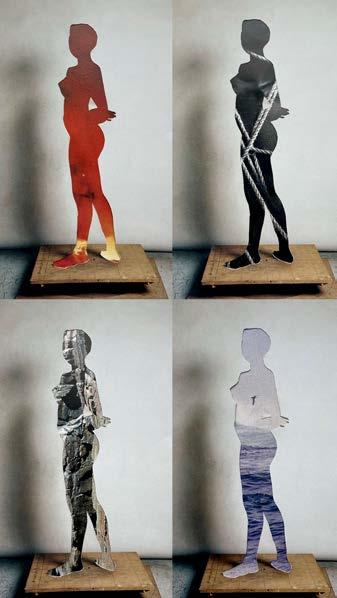

Allow Me to Be by Mai Hedvig Lyngby

Pleasures Erased and Withdrawn by Anna Leander & Alva Guzzini

All hope is gone + Death of Koshej by Liza Shkirando

Nana, they are destroying our planet by Małgorzata Rumińska

PRIDE & FURY by Clara Josephine Lykkeberg

These Boots Were Made For Walkin’ by Ryleigh Avnet

Waitress Broadside by Hailie Cochran

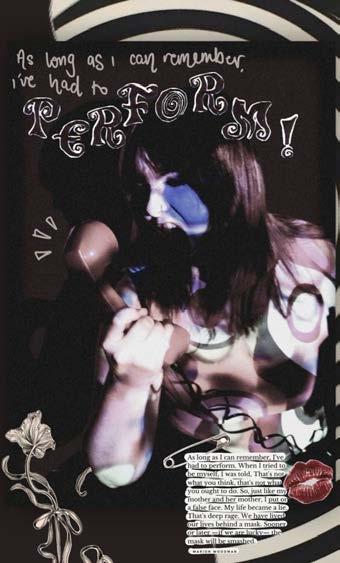

The performer + Violent femmes by Lottie McGowan

Dear people, by Johanne Pi

memories of summer by jane katzmann

Girl, Interrupted by Izzy Blankfield & Nicola Stebbing

Spirals of Silence: Feminist Rage for Greenlandic Inuit Women by Anastasia Kluge

Hooks by Giovanna Saturni

Abécédaire of RAGE by Zélie Lézin

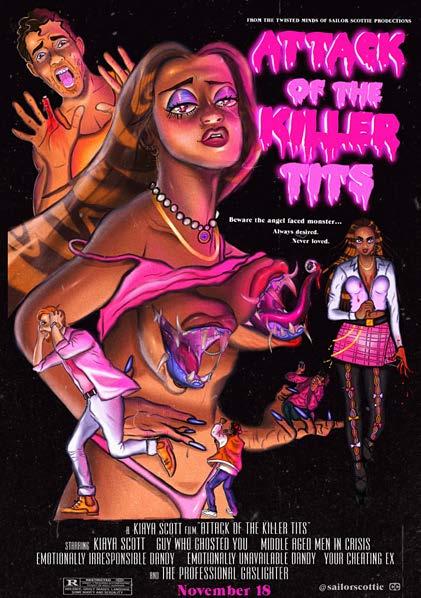

Attack Of The Killer Tits + TRAMP(led) by Kiaya Scott

The Suit by Tone-Lise Havnbjerg

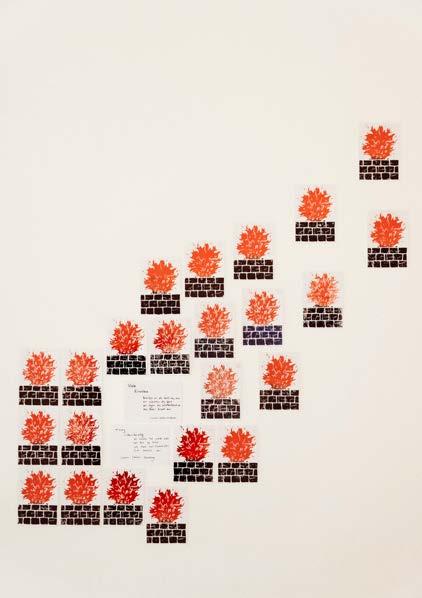

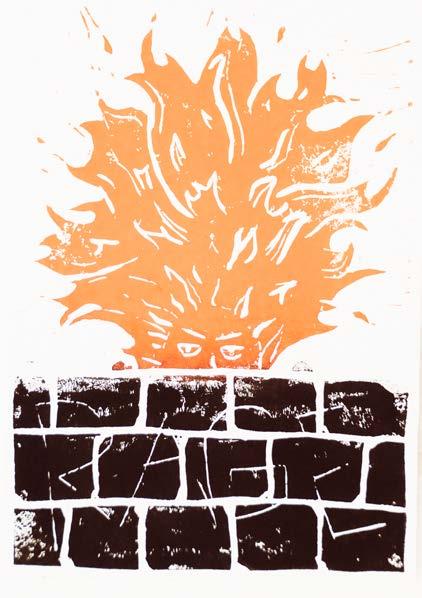

Burning Army by Vera Zimmermann

Dusk Rituals

forethought on a Dream by Eleni Gemitzis

Viper Monarch by Nathaniel Remon

Letter to Medusa by Momo Mentha

Death in a Postwar High Rise on Main Street by Tara

On running through quicksand / The weight of what should be by Sophie S.

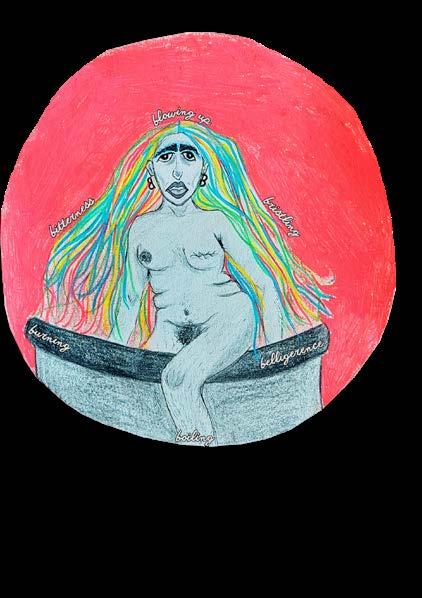

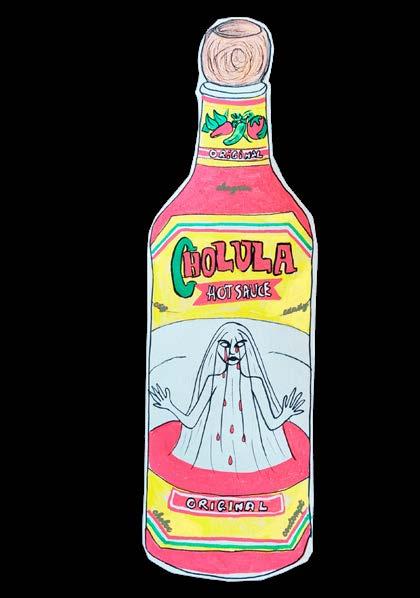

Internalized Rage by Georgia Evans

Contributors & RAGE Collective

RAGE RESEARCH continues/d

Dearest reader,

In the world of rage, I’ve set out to explore, discover and examine what rage is and how we can understand the phenomenon. My quest with rage started almost two years ago and turned into this creative research project, Rage Research, where I interview people to get a closer understanding of rage. You can read the first part of this raging research series in RAGE Zine Vol. 1.

The quest continues.

Through new interviews with the editorial group and with psychologists, both reoccurring and new perspectives have come up, and so we continue to unfold and discover the sides and edges there are to rage.

Moreover, this research project welcomes you into your own reflections upon rage. Try to sit with your rage for as little as 20 minutes. Think freely, write freely, sing, dance or...? The two open questions in this edition of Rage Research are: What is rage to you? How do you let yourself rage?

No answers or emotions are inferior to others, and with this ongoing research project, I wish to broaden our understanding of rage, reflect upon our own rage, and make space for this powerhouse of an emotion. Rage Research last explored when people tend to feel rage; the feeling of the world and/or people being unjust and feeling helpless can provoke rage. This theme reoccurred in the present study which found that rage can come from feeling powerless. Additionally, the previous interviews from Vol. 1 presented me

with the stages of rage. An idea that the initial stage of rage is raw, destructive, and unproductive, followed by a stage of action – a creative and productive state. I understand these stages as intertwined. In the present edition of Rage Research, the interviewees all spoke of rage as a powerful, big, uncontrollable, intense force or passion. However, the focus was much more on the need to express your rage. I am tempted to interpret that there was a great emphasis on the stage of action Rage is a natural emotion that we need to express –this resounded loud and clear across all interviews. In the midst of feeling powerless and overwhelmed by rage, expressing rage on your own terms can be a form of reclaiming your power or agency. Rage is a natural part of you.

Unfortunately, rage has a negative connotation for a lot of people. It is my experience, as a therapist, that rage is often labeled as a ‘bad’ or ‘negative’ emotion, which carries a lot of shame. Therefore, it’s often complicated for people to express their rage. But repressed rage can be and feel quite destructive. Several of the participants in this study reported that repressed rage can lead to distress, physical stress, stagnation, or even sickness. This is no new idea, from ancient holistic medicine to new studies on how repressed rage directly influence the development of autoimmune diseases in women.

Can you acknowledge rage as a beautiful part of yourself? You are rage, rage is you.

Honoring your rage

As a psychologist, editor, and researcher, I walk with wonder, I observe, explore and engage: How can we let ourselves rage? Based on the conversations about rage that I’ve had with editors and psychologists, some important findings surfaced. Together, we dove

into the practice of rage. Meet your rage with compassion and curiosity. First, A W A R E N E S S – to become aware of what’s happening in you, your mind, your body. Allow yourself to feel and be with rage. I was particularly fascinated by the idea of honoring one’s rage. To honor rage by noticing her, allowing space for her – as a way of creating space for yourself, your whole being. Let me elaborate: letting yourself feel rage, expressing your rage (your emotions) is honoring yourself and giving yourself space in the world. As was voiced in the interviews, repressed rage can have destructive consequences and cause discomfort, which is why we must take her seriously by noticing, feeling, and honoring her.

During the interviews, rage was presented, felt, and voiced from a soft place. One psychologist pointed out to me that rage is such a vulnerable emotion because it clearly shows (us and others) what matters, what hurts, and what our deepest values are. These feelings almost force us to think about our own power and how to act on it. Another participant talked about rage as a strong connection to themselves, almost as if rage was a channel that opens up a piece of you and connects you more intimately to yourself. ‘Rage is something everyone has agency towards’ (Keni Nooner, Digital Editor and Events of RAGE). With this, I understand that we are all emotional beings with the right to feel and express ourselves. That every being has agency to choose what to share, and what stays in their inner world. Most importantly, ‘try not to judge yourself’, another psychologist said.

An important part of the conversation is the expression of rage. Multiple participants mentioned creation and creativity as important ways to express, act, channel and/or understand their rage. Another inspiring idea in the conversation about rage is the

importance of community – finding safe pockets of support, where you are free to rage. Where rage might even become unifying.

A third noteworthy theme that reoccurred in multiple interviews was physical movement. Honoring your rage means noticing, accepting, and welcoming it. Movement, whether it’s swimming, yoga, dance, or running, can create a sense of freedom in the body and thereby space to feel (rage). To give yourself space and an opportunity to be free in your body will create a sense of freedom in your emotions. To move your body can be a way to channel and express your rage (honor your rage!).

Like a hot damp train engine, heating builds up and needs to come out. Like a water dam, you need to open up and let the water flow. Like lava in a volcano, building up and exploding. Like a warm force pumping through your veins, rage wants to be seen, wants to be heard, wants to be expressed. These are all metaphors from the different interviews.

Find your own rage rituals. How can you let out steam? How can you rage? No matter how and what works for you, hold your rage with love.

As always, I would love to hear from you if any thoughts, emotions, or comments came up during your reading of Rage Research. Feel free to DM @ragezine with the heading Rage Research. Thank you.

by Roselil Aalund

MY RAGE PAGE

Name

Birthdate / /

Zodiac sign

Rage is

I love to rage, when

If my rage was a pet, it would be

When I feel rage, I feel it in my body.

I let myself rage Never Often Not enough Rarely

My biggest support, when I feel strong emotions is Space to rage

created by Roselil Aalund

I rage, fingers cracked open, scraping your skin until it bleeds, and still I want to hold you, to touch you soft, but my hands? they carry the weight of a world that never held me. I am fury wrapped in silk, eyes gentle, but my soul? my soul is a tempest. Does this mean I am a lie? Or is it that the truth is too wild for you to see? Rage was passed down like a legacy, worn on our backs like woven cloth, my mother wore it, and hers before her, bodies of stone, hearts made of fire. Indigenous and bold, our blood burns in forgotten tongues, mountains in our bones and oceans in our eyes. We have always raged. Always will. I love you, but I am afraid to let myself melt for you— I have been forged in anger, tempered in the furnace of a world that forgot us. It burns, it cuts, it leaves me raw and restless, wanting to be soft, but terrified that softness will make me disappear. I have been running from myself before I knew how to walk, a stranger to the skin I was born into, hiding in corners, waiting for the world to be kind. But the world was never kind. It wanted me to quiet my roar, my fire, wanted me to shrink into a shape that would fit their cage. I refuse. So now I rage. I need someone to kiss the dark parts of my spirit, to hold my storm with open hands, to see me, to see the rage and still love what remains. I need to put this fire somewhere, need it to rest, to cool, but the burn is all I’ve ever known. So I need to feel something else. Something not made of ash.

SOMEONE COME AND KISS MY RAGE

by Farah Bejdadi

by Troty

I fill my mouth with female rage

by Julia Marie

it’s a tiresome truth that there’s no tolerance for a woman’s anger so when a storm starts brewing behind my belly button and my eyes fill with water so hot and steaming it feels like my gaze could break the space time continuum but never the silence in my empty mouth

my spiky tongue can’t form the words for punching pain all the way down my throat

my tense and strong abdominal wall contracts I gag and spit besides it all a densely woven hairball

each string and strand of golden rage I swallowed I loudly laugh with shining teeth and set it all on fire

by Liz Walker

RAGING VOICES From Post-Election USA

Few elections are as closely watched as the U.S. presidential vote. From the inside, by the majority of Americans divided between Democrats and Republicans, and those oscillating in between. And also from the outside, by global onlookers eager to know the outcome of this particular election that doesn’t just shape internal politics, but also sets the tone to the rest of the world on what to expect from one of the heavyweight global political powers. The 2024 vote set itself apart from the rest in the relative predictability of its contestants, but unpredictability of the outcome – and in the fact that several communities had much to lose. Trump’s second term – despite its chaotic messaging and conflicting decision-making – has clear objectives in mind: backtracking on the rights of women, queer and immigrant Americans, undermining rule of law, withdrawing from countries in need and, most importantly, making (more) money. And to achieve these ends, befriending big business, tech giants and fascists is not out of the question. Now that this agenda is fully in motion, what of the US citizens and residents who now witness and experience attacks on their rights and identities as the new normal? Are they scared, anxious, grieving? Probably. And are they raging? Most definitely.

This piece combines a range of raging voices from post-election USA, to look back on what went wrong with the last election, take stock of the (terrifying) trends that are unfolding at present, but also look towards the future – what can be done by those who refuse to stand on the sidelines in silence?

Aftermath: drained, demoralised but driven

Some were sure, some were scared, others were sceptical. Common to all were the feelings that followed the announcement of Trump’s second term. Some had invested heart and soul in the Democratic campaign, certain that it was not only the right choice for them, but the one that most Americans in their right mind would choose: “Devastatingly, I was so sure. I hate to admit that now. Working at Harris HQ, surrounded by campaign leaders and dedicated volunteers, we all felt it—the momentum, the energy, the certainty that we were part of something unstoppable. It never even crossed my mind to prepare for the possibility of losing. How could we? We were on the right side of history, and surely, goodness would prevail. Looking back, that confidence feels naïve, and it’s painful to revisit.” (CM) Others were torn in between bad and worst, between two parties that both would continue supporting Israel’s killing and destruction in Palestine and surrounding territories: “I watched my Syrian husband’s pain when voting for Kamala Harris because the alternative is just terrible, but at the same time knowing that the Democratic party are putting his friends and family in serious danger and destroying his home country.” (RA)

In the aftermath, the feelings of defeat, disappointment, but also fear, were felt by all, in particular at the fact that the “motivating factor of hatred” guided the Republican campaign and seemingly spoke to large swathes of the American people (CW): “The anger and let down of the majority of the American population who voted who decided to bring someone back into office who caused so much confusion, suffering and division. … I have lost what little trust I had in the future of the American people to help our country move in a direction of sense, empathy, or at least a shared reality.” (LG). And this goes beyond this particular election and the specific campaigns and policies promoted, “it’s about the way leaders talk about people, the tone they set for the next generation” (CM), which denigrates the identities and rights of millions of American people.

Trump’s win is deeply scary for communities living in fear of attacks on their identities, but also for everyone wishing to access basic services and have their fundamental rights upheld. “I’m scared for my potential child living in a country where the regulations around clean air, water, treatment of hazardous material are all being undermined, where the education structure we have in place is being threatened, for continued limited gun regulation and the violence that ensues and kills children.” (LG) One option is to leave the United States to escape from a government that deliberately does not guarantee support and protection of its people: “My partner and I have discussed moving with his additional passports out of fear of very real violence occurring or need due to medical concerns.” (LG) But for many, leaving is not an option…

Facing the facts: fascism is back

Most knew what a Trump win meant in terms of far right-leaning politics, but few would have predicted that it would go this far – all the way to outright fascism. The first few weeks of the presidency provided a clear preview of what to come: “a coordinated attack on basic, fundamental rights and freedoms of US citizens, residents and migrants, as well as beneficiaries of US-funded development programs abroad.” (Anon). More worryingly, the Republicans now exert control over the executive, judicial and legislative branched of government, so the country is likely to “continue to see decisive blows to human rights, social justice and sustainable development both domestically and internationally.” (Anon). In the midst of unabashed fascist gestures, a flurry of far-right executive orders and hate-inducing speech illustrate the government administration’s push to break the norms and standards of politics and diplomacy,

the tone towards those in power remains (too) cautious: “naming and opposing American fascism has become so unnecessarily difficult in the realm of institutional politics.” (NC). While some pushback has happened at the state judicial level, the Supreme Court is unlikely to exert checks on Trump’s executive decisions: “I’m deeply concerned about the Supreme Court of the United States and the ability of federal judges to serve as a bulwark against Trump. The judicial system is already skewed to the right due to the disproportionate number of Trump-appointed justices and judges, any additional appointments would be devastating.” (CM)

This populist tone can be clearly felt in the discussion on immigration. While it has always been a contentious topic, past politicians have always threaded cautiously on a topic affecting a majority of Americans. Now, the status quo has clearly shifted to a full-fledged anti-immigration campaign, where human beings with sometimes years in the US are being treated merely as ‘aliens’ on foreign soil. In a country built on immigrant labour and priding itself of providing opportunities to ‘dream’ of a better life, immigrants now feel unwanted and threatened (LG) – at least those who have precarious legal status, while mill/billionaires can simply pay for the ‘golden’ visa tabled by the new administration. It is therefore impossible to separate the electoral result from “systemic racism and misogyny [that] remain part and parcel of our

political establishment, which was founded (and in many ways still run) by white, wealthy men.” The ‘rejection’ of Kamala Harris in favour of Donald Trump seems an illustration of this deep-seated opposition to – and fear of – women, people of colour and minorities gaining power. And the somewhat misguided idea that, as a result, the white male ruling class would lose from this power shift: “On the surface, Kamala Harris - as a Black and Brown woman - represents a ‘threat’ to this state of play, and the US media hellscape coupled with her vitriolic opposition did the work of contributing to racist, sexist narratives against her and her agenda.” (Anon)

Finally, looking outward, the Trump administration’s stance is equally hellbent on looking inward, pushing to profit the most and sacrifice the least of ongoing conflicts across the globe – some of which it has actively or indirectly fuelled or started: “While the administration seems to prioritize a general ‘anti-war’ rhetoric, when it comes down to the rights and well-being of folks most impacted by these global conflicts (e.g., Palestinians, Ukrainians, etc.), it places US interests before all (i.e., ‘America First’).”

Those behind the votes: usual and unusual suspects

The typical Trump voter is what you would expect – but this time around, the reasons for their vote were arguable more deeply anchored in disinformation narratives powered mainly by social media. Trump’s self-projection “as a kind of political maverick” (NC) appeared to appeal to many Americans as well as the misguided hope that he would be able to ‘fix’ the economy and support the millions of Americans struggling to make ends meet, may have pushed some to prioritize economic policy over other core issues, such as reproductive justice (CW). In addition, social media played a decisive role – as a new “playground for extremists” (RA) –in labelling certain news and outlets as ‘liberal’ or woke’, “pull[ing] people away from receiving real objective news and steer towards entertaining, fear inducing, simplification of news.” (LG). These disinformation tactics had a clear impact: “In conversations with undecided and Republican voters, I saw firsthand how deeply

right-wing propaganda had shaped their perceptions. Many dismissed Kamala Harris as unqualified, often citing sexist misinformation, including the false claim that she “slept her way to the top.” (CM). Worryingly, many of those who readily embraced these narratives were younger people, young white men in particular, increasingly “turning to more conservative and regressive political narratives in the current landscape.” While this is a symptom of a larger push-back against feminist and inclusive policies, a fear-induced grab to safeguard traditional perceptions of masculinity, “watching the shift of young men to the right feels like both a terrifying political trend and a personal attack. When the rights of all of your fellow female peers are at stake, that’s personal.” (CM).

While it is tempting to solely blame the ‘usual suspects’ for the Republican win, Trump’s voter base seems to have increasingly expanded, speaking to a wider range of voters interested in disrupting the status quo of traditional politics and US governance. For one, “Trumps anti-corruption argument goes far [and] general distrust with the establishment.” (CW). This includes more and more young people, not only leaning into Trump’s anti-establishment politics, but breaking with traditional political parties all together: “US citizens my age and younger [29 years old and younger] are completely disillusioned with our political establishment - to say the least. I know many peers of mine who either abstained from voting this election cycle or chose to vote third party, citing mostly a deep disappointment in Democratic leadership on both domestic and international issues” (Anon). Not only that, but many white women, Latinos and Black men voted in favour of a system oppressive against their own identities: “Americans who voted against their own interests [were] just voting for themselves—they were auditioning for acceptance into the white male power structure. And the saddest part? It won’t work. No matter how hard they try, they’ll never truly be let in. They’re just pawns in a game rigged against them.” (CM)

At the end of the day, the reasons for Trump’s win and Harris’ loss are both “frustratingly predictable and deeply unsettling. At the core of it, there was a powerful mix of fear, misinformation, and cultural backlash. … Because

too many people are willing to abandon their own for a seat at a table that will never really be theirs. And because, at the end of the day, some people would rather burn it all down than share power.” (CM)

A win for big business and money makers

What stands out particularly from the outcome of this election, is that it did not only represent a win for the Republican party and its supporters, but also a very public win for big business. Not to say that previous races did not have significant private sector involvement and influence – as U.S. politics are notorious for their shady links with private companies and wealthy donors – but for the first time, there was decisive publicity and courting of Trump and his political allies by multinational companies. Somehow, Trump’s win made away with ethical reservations and saw a parade of tech CEOs showcasing their support, not only by attending the inauguration, but also immediately adopting Trump policies such as the push against DEI hiring processes. The cause? Likely a mix of seeing an opportunity for profit under a President uniquely associated with making more money for American businesses; a sense of fear that unalignment with this administration would negatively impact companies; but also a group of predominantly (white) male CEOs riding the pro-masculinity and anti-woke wave to the fullest.

Whatever the cause, “that there is such an outright influence of specific people and their business needs on such a large reaching scale is terrifying” (LG) and sends the clear message that “money goes before anything” (RA) and that the ethical line between public service and private interest has been purposefully erased. The fact that an unelected official with clear business interests in the tech and social media industries has been appointed to head a Department in charge not just of these specific policy areas, but also of human resources across the state apparatus is not just outrageous, but dangerous: “anything that makes Elon Musk happy is a net-loss for the human race.” (NC). In fact, it is not just that private interests have trumped public ones – it is that the public

sector is deliberately being undermined, civil servants with a wealth of knowledge and experience fired, and crucial development aid to countries facing outbreaks, famine, conflict and displacement scrapped from one day to the next.

As things stand now, this is playing out like a bad apocalyptic movie – so,

What next?

These elections are not an isolated event confined to the US political bubble. Rather, they reflect and confirm a political tone around the globe that rejects promotion and support of fundamental rights, the recognition of identities and diversity, and, democratic governance as a whole – in favour of economic growth, business and investments, and hard-line policies that limit self-expression and the recognition of individual and differentiated rights and protection. Despite what Trump and his team want to project, this populist logic is not American made, but spans all corners of the world including Argentina, Hungary and India. The difference, however, is that until now the US has had its hands deep in various international contexts – from its funding to NATO and UN agencies, to its role in ceasefire and peace mediation in Palestine and Ukraine – and its shift towards an America first policy and a both nonchalant and lecturing attitude towards (former) allies has put the rest of the world on its toes, to say the least. So far the response to various US U-turns in foreign policy have engendered rather shy responses – notably on tariffs, Greenland, Gulf of Mexico. While Europe talks of standing on its own and China barely bats an eye, populist and far-right agendas keep gaining ground in Europe and Latin America while authoritarian regimes strengthen their grip on power in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. On the international stage, prospects of resistance to the Trumpian narrative remain bleak for now.

But within US borders, among the people most vulnerable and affected by Trump’s policies, there is still some hope on the horizon: “We’re not gonna let up -- none of us

will. Because we can’t. This means speaking more unabashedly about our abortion stories, developing greater networks of mutual aid or just becoming really scrappy and strategic ahead of 2026 and 2028. The right wants us exhausted, divided, and demoralized— but they’ve underestimated us before, and they’ll regret it again.” (CM). But to rage and resist means to confer and commune, so there is hope in promoting “a resurgence in collective action and resistance to these concerning trends both here in the US and abroad. People-led mobilization across movements, sectors and geographies have accelerated progressive, transformative social justice and rights-based agendas in the past and have the potential to do so now and in the years to come.” (Anonymous) One example is the Movement for Choice based in Washington DC, especially vulnerable to attacks on reproductive rights: “Right now, we’re taking it day by day. Our focus is on creating safe, joyful spaces for people who care about reproductive justice and on supporting the abortion providers who are on the frontlines of this fight. They’re doing the hardest, most important work, and we’re here to stand with them however we can.” (CM).

In conclusion: “it looks like some things are going to stay bad, some things are going to get worse, and any good comes from us. It’s true what they say, at least for now: we keep us safe.” (NC)

by Mathilde Betant-Rasmussen

With contributions from: Caroline M., Carol W., Lauren G., Nicholas C., Roselil A., and others.

Q&A with Caroline Motley, Movement 4 Choice Founder

Caroline Motley is a graduate student at George Washington University’s Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and the founder of Movement for Choice (M4C), a nonprofit supporting reproductive justice through grassroots fundraising and community events. She previously served as a volunteer coordinator in the Harris Presidential Campaign, leading large-scale field operations in battleground states. In her free time, Caroline enjoys long walks, thought-provoking podcasts, learning to play the piano and plotting the downfall of the patriarchy.

Movement for Choice is a DC-based nonprofit advancing reproductive justice through community care, joyful movement, and grassroots action. We organize donation-based fitness classes, mutual aid, and storytelling campaigns to support abortion access and reproductive freedom — especially for Black, Brown, queer, and trans communities. As a proudly feminist third space, we build community power through embodied activism, unapologetic advocacy, and revolutionary joy.

[RAGE Zine] What were your key motivations for working for Harris HQ and on Kamala Harris’ campaign? What was your role exactly?

[Caroline] Honestly, deciding to work on the Harris campaign was the easy part. The hard part was actually getting the job at HQ—it took a lot of persistence. I wanted to be on this campaign because I knew this election would shape not just the next four years but the next several decades. And not just in the U.S.—for people around the world, especially those most vulnerable to bad policies.

At the core of it, my biggest motivation has always been fighting for women. There’s a Yiddish word, beshert, which means destiny or fate. It’s also used to describe a soulmate. I think of gender equality as my beshert—the thing I was meant to fight for. More specifically, I joined the campaign because I care deeply about reproductive freedom and making sure marginalized communities—women, immigrants, LGBTQ+ people—are treated with dignity. To me, this is bigger than policy. It’s about the way leaders talk about people, the tone they set for the next generation. I worry about what young men, in particular, are being told about masculinity, that somehow their power or happiness comes from putting others down. It’s a dangerous lie.

At Harris HQ, I managed the “Surge Volunteers”—tens of thousands of people from “blue states” who traveled to battleground states every weekend to knock on doors. This was only possible because the campaign had the money to fund it, which is pretty rare. I went on a lot of these trips myself, traveling from DC to rural Pennsylvania, and I’ll never forget the people I met—a father fighting for his transgender child, a Latina woman with undocumented loved ones, a young woman terrified about what would happen to her reproductive rights. When I think about my time on the campaign, I think about them.

Did you have to defend your point of view on the elections to people around you? How did that make you feel?

I worked on the Harris Presidential Campaign, where part of my role was leading volunteer groups in rural Pennsylvania. Our challenge was twofold: persuading voters to consider supporting a Democrat in the first place and ensuring registered Democrats showed up for Harris.

In conversations with undecided and Republican voters, I saw firsthand how deeply right-wing propaganda had shaped their perceptions. Many dismissed Kamala Harris as unqualified, often citing sexist misinformation, including the false claim that she “slept her way to the top.” These moments were particularly difficult for me, as my instinct was to push back defensively. Despite feeling completely disgusted and insulted, I was forced to make a conscious effort to stay composed as the goal was to hopefully change their minds. A key to effective persuasion is to practice tolerance, patience and understanding. As a feminist who has never shied away from confrontation in my life, this was incredibly challenging for me. I did my best to focus on presenting facts about Harris’s extensive qualifications and engage with voters’ concerns to find common ground.

How would you describe your feelings in the lead-up to and during the elections?

Devastatingly, I was so sure. I hate to admit that now. Working at Harris HQ, surrounded by campaign leaders and dedicated volunteers, we all felt it—the momentum, the energy, the certainty that we were part of something unstoppable. It never even crossed my mind to prepare for the possibility of losing. How could we? We were on the right side of history, and surely, goodness would prevail. Looking back, that confidence feels naïve, and it’s painful to revisit. I believed so deeply in what we were fighting for that I never allowed myself to imagine a different outcome. We fell in love with a dream and America broke all of our hearts. We wanted better for this country than it wanted for itself.

Can you describe what it felt like, as a campaign staffer and personally, when Harris lost the election?

Oh man. I still get choked up thinking about it. The moment that sticks with me is an email HQ sent out when the results started coming in. The subject line was We feel good. A few hours later, it was over.

On November 5th, I walked out of the voting booth feeling weightless, convinced I had just cast my ballot for the first female president of the United States, a champion for the people and women, most of all. For months I was surrounded by people who felt just as certain as I did. “We’re going to win this thing,” every all-staff meeting started.

And then, within hours, that certainty crumbled into something I can only describe as grief. As the votes were tallied, I sat frozen in disbelief, my mind unable to process what was happening. By 9 p.m., my body caught up to my mind—I found myself over the toilet, throwing up from anxiety, something I had never experienced before. That feel-

ing—stunned, motionless horror—never fully left me. It settled in, lingering beneath the surface of everything. Only now am I learning how to live with it.

I actually feel a little sick when I think back to that night. We gave everything we had. It felt like losing a loved one. We were exhausted, drained, and just... devastated.

Who are you most angry at and what are you most angry about?

This is a tough one. I’m angry at a lot of people. Honestly, I’m always angry at white men—because, seriously, fuck you for voting to uphold systems that oppress everyone but yourselves. How original of you. But what really makes my blood boil is young men voting for Trump. How are you 18 and already so jaded and angry? At 27, watching the shift of young men to the right feels like both a terrifying political trend and a personal attack. When the rights of all of your fellow female peers are at stake, that’s personal. That said, I don’t expect much from them. What really stings—the thing I can’t shake—is the Americans who voted against their own interests, their own identities. I’m still trying to make sense of it. Specifically, the Latinos, Black men, and white women who backed Trump. I guess they’re just voting for themselves—they were auditioning for acceptance into the white male power structure. And the saddest part? It won’t work. No matter how hard they try, they’ll never truly be let in. They’re just pawns in a game rigged against them.

Why do you think so many voted for Trump/against Harris?

Many people voted for Trump or against Harris for reasons that are both frustratingly predictable and deeply unsettling. At the core of it, there was a powerful mix of fear, misinformation, and cultural backlash.

First, there’s the fact that right-wing propaganda is *wildly* effective. I saw it firsthand while canvassing—people genuinely believed the most absurd, baseless lies about Harris. The right has mastered the art of weaponizing misogyny and racism, and Harris, as a Black and South Asian woman in power, was an easy target. She was never going to be judged by her credentials alone, no matter how extensive they were.

Then, there’s the shift of young men to the right. It’s not just ignorance—it’s entitlement. It’s the panic of people who were promised they’d always be on top, watching the world change around them and scrambling to protect what they think is theirs.

And then there are the voters who went against their own interests. The Latinos, Black men, and white women who cast their lot with Trump weren’t just voting for a candidate—they were chasing proximity to power. Somewhere along the way, they decided that aligning with white male supremacy would serve them better than solidarity with their own communities. And the cruel irony is that it won’t work. They’re still pawns in a game where they’ll never truly win.

So why did so many people vote for Trump? Because fear is a hell of a drug. Because misogyny and racism are baked into this country’s DNA. Because too many people are willing to abandon their own for a seat at a table that will never really be theirs. And

because, at the end of the day, some people would rather burn it all down than share power.

What next? What will the next four years look like for you and/or those around you in this political context?

Oh gosh. I think the next four years will look like good trouble. We’re not gonna let up -- none of us will. Because we can’t. This means speaking more unabashedly about our abortion stories, developing greater networks of mutual aid or just becoming really scrappy and strategic ahead of 2026 and 2028. The right wants us exhausted, divided, and demoralized—but they’ve underestimated us before, and they’ll regret it again.

As the Founder of Movement for Choice, how will your work be impacted by the election? What are the key things you’ll be doing to continue the fight for abortion rights and bodily autonomy over the next four years?

I think about this all the time. Movement for Choice is based in DC, which makes us especially vulnerable to attacks on reproductive rights. The clinics we work with provide care to people from all over the country—people who have to travel here because their states have made abortion nearly impossible to access.

Right now, we’re taking it day by day. Our focus is on creating safe, joyful spaces for people who care about reproductive justice and on supporting the abortion providers who are on the frontlines of this fight. They’re doing the hardest, most important work, and we’re here to stand with them however we can.

Given your experience working on Harris’ campaign and leading a reproductive rights nonprofit, this election has impacted both your personal and professional life. How do you navigate the emotional weight of it all? How do you manage your anger and use it as a force for movement-building, solidarity, and community strength?

First of all, I really appreciate this question. Because if I’m being honest? It’s fucking hard. Some days, I just can’t do it. I stay in bed and avoid everyone. I’ve also had moments where I snapped at someone in a MAGA hat... and I’m here to say that it actually felt... really good.

The only advice I have is to let yourself feel everything. The grief, the rage, the exhaustion. Don’t bottle it up. But also, do your best to find joy where you can. For me, that’s through laughter, especially with the women in my life. No matter how bad things get, we still have each other.

Movement for Choice was born out of grief after the Dobbs decision, and yet, despite everything, this community has grown and persisted. That’s what keeps me going— knowing we’re still here. We’re still fighting. And we’re not going anywhere.

For more information about Movement for Choice, visit: movementforchoice.org

To my fierce Black girls, The world has no fucking idea what to do with your rage. To understand the heat of grief pressed into your bones and the spark of rage tucked beneath your tongue is to understand legacy and power—it is to understand the many who came before and those who will come after. That fire is life within you. It’s carnal, it’s true, it’s natural. Your rage is not a curse.

To my tender Black girls, You carry so much that the world doesn’t see, but I am asking you to feel your rage. Channel the fire. It will be misunderstood—labeled as anger, madness, recklessness, or a lack of love. And that is exhausting. But let them fear it. They cannot take what you won’t give up.

Your rage connects you to your softness. Your rage is the channel to intimacy. Your rage is sacred. It’s palpable. It’s powerful. Your rage is a gift.

To my luminous Black niece, You are the love that sets rage ablaze. I see the light in your eyes that I hope never dies. The fire that burns is the same—let them feel your rage. Felt, it is power. Protect it to protect yourself, to honor your mom, your grandma, and every Black woman who carved a path for you to follow.

Let them witness your rage. Your rage is sacred.

To my Black boys: I’m counting on you to do better. I know your rage lives inside you more than you realize. Accountability is not a cage—it’s a bridge, a force that brings us closer and makes us stronger. If you do not feel what you need to feel, your rage will consume you.

Understand that your rage is tied to the way you treat Black women and girls in this world. Your rage, when understood, is power. Your rage, when honored, is transformative. Your rage transforms.

To all of my young Black children who can’t feel their rage: You have been handed a heavy world that demands your silence, your strength, your restraint. I see the rage you’ve been forced to swallow, and I know what it’s doing to you. But you don’t have to hold it alone. I love you. I need you. Not just your strength, but your softness, too.

Let your grief be heard. Let your rage breathe.

I know this is scary. I will teach you how to wield it without it destroying you. If you learn to hold it, to let it breathe, it will set us free.

I imagine you breathing without weight on your chest. I imagine you speaking, and the world listens.

I imagine you laughing loudly in spaces where no one tells you to be quiet. I imagine you crying without apology and being held until you are ready to stand again.

Not feeling your rage will silence you. Not feeling your rage will kill you. But feeling your rage will save you.

Your rage is not the end. Your rage is where we begin.

Let it burn as a beacon of what’s possible.

Your rage is passion. Your rage is sacred. Your rage is legacy. Your rage is power. Your rage is love.

Rage Is Where We Begin by

Keni Nooner

Essays on Reaction Drop I: Rage

When I didn’t have the strength to react

Essays on Reaction Drop II: Abuses Trap

WATCH ESSAYS ON REACTION DROP I & II HERE

by Mädchen Vivi

STICKERS AND MARKERS, RECLAIMING AGENCY THROUGH DIY ACTIVISM

Métro-boulot-dodo is a French saying used to describe the mundane Parisian’s routine: taking the subway, working and coming back home (only) to sleep. It was popularised in May ‘68 to describe the alienation caused by modern urban life, which contributes to a passive attitude towards the world. This common saying often comes to mind during my morning commute, where half-asleep, I try to squish myself into the crowded rush-hour train. However, sometimes something jolts me out of this routine: a giant out-raging ad.

On the subway platform walls, 4x3 meters of glossy paper are selling me something. A witty slogan, an edited picture, a carefully curated colour palette, an out-of-the-box fresh-out-of-businessschool branding concept, and most importantly a promise: this object will make me happy and fulfilled, this service will solve my problems, this product will make me an acceptable woman, get it or get FOMO. The question “how is such a sexist/ tone-deaf/out-of-touch publicity still possible in 2025?” often comes to mind. These ads are made to create desire, to stimulate consumption and by doing so they shape our identities and ideals. These images reinforce gendered and limiting stereotypes, they sexualise and commodify women. In Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard explains that the domination of images, labels and signs blend fiction and reality to form a hyperreality. The advertisements that surround us do the same, they create representations that become more real than the things they represent. The images of women portrayed in ads are shaped by the male gaze and the Photoshop lens. They encourage diet culture, fast-fashion, skincare obsession, forming an unreal flawless self, a fantasy that is “Killing Us Softly.” In La société du spectacle, Guy Debord explains that the ever more presence of images representing an idealised version of life, form a spectacle. The spectacle of capitalism leads to a form of commodity fetishism, where consumption takes on religious aspects. Guy Debord invites us to break free from our consumer/spectator role.

Day after day, these ads made me so angry, that one morning I tossed a thick black marker in my bag. I called it ‘‘mon crayon de la colère’’ [my rage pen]. I used it to comment and draw on ads, pointing out their negative impact on women, the environment or even the right to housing. This was my way to not actively refuse to endure these images and reclaim space through action. The small act of highlighting a sexist ad may have a big impact as thousands of passersby will look at this modified image. I then wished to engage others in this idea. With my sister, we created DIY stickers and shared them with friends. Collectively, we started sticking them on every ad that enraged us: bank ads, miracle skincare ads, diet clinics ads, fast fashion retailers ads, blatant gentrification ads as well as advertisements including actors involved with domestic assault and violence against women.

What does creative defiance mean to you? What is it you want to speak up about and collectively resist against? With the following tutorial, we invite you not to stay an observer of oppressive images and instead rip them up, cross them out and respond back.

by

Myfawny & Arianell Boudry

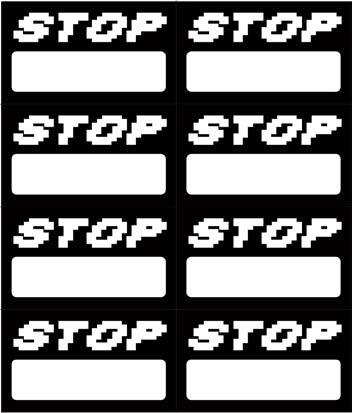

WE INVITE YOU TO ‘SAY STOP’

Step 1: Rip this page with the ‘STOP’ sheets out of the zine

Step 2: Cut out the individual ‘STOP’ sheets

Step 3: Keep the sheets, some tape and a rage pen in your bag at all times

Step 4: Be mad, but beware of security cameras

Optional additional step: Be furious with friends, spread the feminist rage!

Lady Bluebeard

Because of you. I sleep With a gun chained to my waist And feel the trigger From a mouth afar mouthing Your name. Or a song that almost Reeks of you, despite borderline Innocence. What is innocence anyway: The bloodstains wiped off The smallest key. A bargain From your wives. I used To love the idea of your Hidden Chamber. Shame On me. (Out, damned spot.) I must atone. So I invite you to my old mansion. My gift to you: A set of keys, a trigger tag warning not to open My underground chamber. I vaguely shrug And said You wouldn't want to see

by Cally Lim

My buried babies that belonged to you. As if. Of course you snuck down to peek And see rows of skinless sinners Hanging like freshly struck from The Tower. A smoking house of Zeuses For Karma. A wall with Yael’s nails and hammer. You never knew my namesake A huntress. (And take my milk For gall) And in You go, motherfucker. Mark the last words you hearken: Every child I birth from now on Shall sleep with stories of sin And do my biddings: Intergenerational revenge, divine Patricide, the scythe slitting Sisyphean-skinned. Feet to fingers.

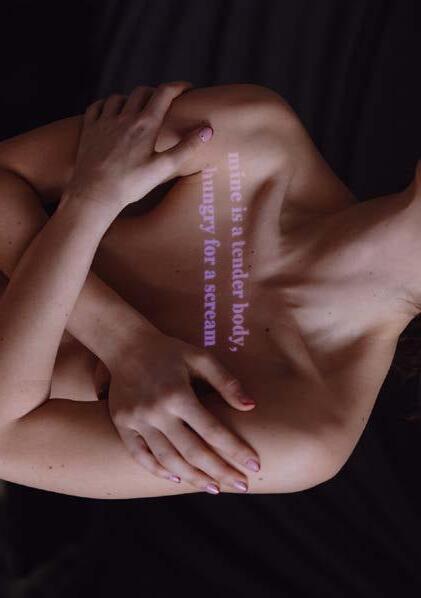

mine is a tender body hungry for a scream, angel soft thighs dying to make a scene, a good-girl-mouth staying silent to extremes, shards of broken words under this pink tongue framed by lip-gloss sheen. my half-moon fingernails clawing on shimmering skin, a nightingale’s song eating up an ugly rage I am holding within. they tell me I was built for love and love and love I am oh so (inhale)

soft (swan)

tender (willow)

Girl, so insane

delicious (fleshhhhhh but oh... no the blood, they love my wide-eyed notnotno- my insanity

I am so sorry I am so

hahahahaha (exhale)

& Body by Laura Griss

by

Mike Haas

Words

Photography

1 a: In the movies, she’s a scarred tale of monstrous rebirth, a reverie of feminine rage wrapped in the silky ‘tsismis’ web of urban legends. The old people, with their tobaccosteepled fingers and birdlike chippers, tell the story of her past. They say she was a hardworking woman who left the country and came back as a monster with a blood-rot sinister clot in her eyes.

b: I was nine, naïve, and my navel brimmed with questions; my great-grandmother warned, ‘She hates children. She eats them mercilessly.’ My fear is a prey of metallic tang, a virile blood lure for the woman with a knife-sliced scar on her face. From the dusk-speckled sky, my hands touched the fields, and I thought of her talons clawing into the ground. The land is a clone of the color of my skin: flesh-browned with a pepper of sun boils and wheat-whittled scars. My mom beckoned for my name, a thunderclap amidst the frivolity, and it’s a warning, it’s a calling, it’s a haven from the woman who feeds. Her name is

2 a: extracted from the Ilonggo word for hack ‘labo.’ The word paints a picture of grinning chainsaws with their brrrrr brrrrrrrr brrrrrrrrrrr teeth and bite. It is the splice of cutting tools with their gleaming sliver of moon retaliating against the dark.

b: They say she ate her own children. Crack open her body, and it’s a visceral shrine of macabrity and decay. Her name was immortalized in a media mythology: Maria Labo. The first film being released in the year 2015 was an exploration of feminine monstrosity representation through the art of visuals. And I remember being in my beigecramped room — the movie hightailing to its climax and curdled brutality. My lips were snarled from the shadowy reflection of the television, and I couldn’t help but be awed in fear by the slight resemblance. It was also the same year

3 a: that my father cradled alcohol bottles to his chest, nursing the comfort of lulled agony with every sip. The legend narrates that Maria Labo disappeared after witnessing the volition of her crime. The old people berated; she was never gone. She roams the creeks, crannies, and concaves of dark.

b: It was also that year I prayed to the moon but still dreamt of hair explosions, mouth dripping in blood, bared teeth, and talons clenched in fists. Every face for every nightmare was a woman with a jagged scar on her face. Soon,

4 the nights were drenched in knuckled bruises and star-shaped imprints. The blood trickling from her chin morphed into beer-spilled, curdled words from a man’s beard. Film strobes against tangled hair didn’t speak of wilderness; it sang the audacity of decrepitation clenched with stubby hands. The teeth, ready to bite unlatched like Pandora’s box, were the color of urine and macho authority. The fists rained like bullets, and Maria Labo seemed to be a better fate

5 to become. Perhaps Maria Labo is a reminder of terror of what a woman could become in the face of grim darkness. Is she a mirror that wives hold up to their faces so that they can see the allure of unrestrained destruction? Or maybe in

the commodity of anger, she became an unpopular metaphor for fire. A wick of flame within teenage girls’ bodies, innately nurtured with neon nails until the day it is permissible to transform as a conflagration. I watched Mom drag herself away into the cavity of wrath as they toppled the decks of her testaments of unjust. They branded her testimonies irresolute, unfaithful, and a destruction to the sanctity of marriage. Is it love

6 if it’s invasive? When Maria Labo tore the flesh of her children, did she ravage and consume her creations whole? Was it for the purpose of reclaiming her power and identity? When she crouched into the ground and lost herself willfully into nothingness, could it be called autonomy? Did she lick her nails clean and wipe her tears with guilt? When she ripped bodies into pieces and devoured the whole of them with insatiable greed, was it a way to abscond for revenge unfulfilled? I asked the questions

7 to my great-grandmother when she called Mom hysterical. When Maria Labo succumbed to her violence, her lips bristling with viscera, her eyes goaded with remorse, did she become herself by choice? Or was it predetermined by ruination? She gave me a terse gaze and whispered, ‘You are still young. You know nothing.’

8 and I keeled and snarled and bit through the tears. My hunger was unsatiated with a patronized pulse, but I knew through my fury. I knew everything with a canine grit. Did Maria Labo repel against her morals and regress into her primitiveness? I wished I knew so I could birth it as an answer to annihilation.

by Dan Aries

Maria Labo

Woman as Object: Bouquet

by Juliana Stankiewicz

A FF ECTIVE (T)E RR OR:

HYSTERIA AS A FEMINIST DIALECTIC OF RAGE

revolution from the margins of reason / the abject as archive / the politics of affect: feelings (often dismissed as irrational or unmanageable) are potent weapons against domination, power, and oppression—both intensely personal and politically explosive. there is an urgent need for us to embrace emotion, rage, and desire not just as individual experiences but as deeply transformative forces that challenge the status quo, disrupt traditional structures, and engage in a kind of revolutionary terror—a visceral, embodied violence against systems of control, through emotional upheaval.

‘‘In my life politics don’t disappear but take place in my body’’ – Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School

‘‘… of all the nervous disorders of the fin de siècle, hysteria was the most strongly identified with the feminist movement’’ – Elaine Showalter, The Female Malady

hysteria (my definitions):

diagnostic framework serving as a way to neutralize women’s critiques of the political economy, framing their distress as individual pathology rather than as a legitimate social critique.

women’s emotional responses to systemic inequalities frequently framed as personal issues to be managed through therapy or medication, rather than as political responses to structural oppression.

I. prologue:

a symptom or a spell? hysteria as suppressed rage

hysteria has long been framed as a medical and pathological condition, often attributed to women’s supposed irrationality, emotional instability, or weakness. however, beneath this medicalization lies something far more profound: hysteria as a form of suppressed rage. rage that has been demonized, denied, and categorized as pathological in order to prevent women from expressing discontent. hysteria was historically used to suppress expressions of power and anger, particularly in women and marginalized groups. what if the symptoms of hysteria—screams, fits, and emotional outbursts—were not signs of illness but rather signals of a politically charged resistance to the subjugation of women, queers, and racialised others?

diagnosis or incantation?

hysteria as a summoning, the pathology of power affective glitching

HYSTERICAL RAGE IS MY MOTHER TONGUE

disjointed

I am ripe with the juices of despair

they archived our bodies in the taxonomies of masculine terror aberrations

brittle medical etymologies

THEY TRIED TO MEDICATE MY RAGE, I MADE IT CONTAGIOUS INSTEAD

spoke in tongues not yet written untranslatable we glitched the language of the empire

witches, neurotics, diseased our bodies faulty architecture in their eyes spasm in the archive, flesh opens with a rupture feral twitches, she bleeds a narrative loop, stammer, around and around, repeat ill or merely illegible?

generative, explosive force the abject disturbs identity, system, order. leaky, squishy, dripping with contamination disciplinary regimes produce mad mad mad bodies delirium transgression

excessive affect disobedient pleasure incendiary speech gendered contamination subversive eroticism

II. history: the weaponisation of hysteria against women, queers and the racialised other

hysteria is not a private affliction; it is a collective wound. It has been the cudgel of history, swung with surgical precision against women, queers, and those deemed ‘other.’ Ancient Greece was the cradle of this diagnosis, and it spread like a virus, infecting every institution built on the bones of patriarchy. the hysterical woman, the ‘irrational’ queer, the ‘disorderly’ racialized body—all were made objects of fear and control. The diagnosis was not just a medical tool; it was a political one. hysteria was wielded as a sword, cutting down dissent, locking bodies into submission. It erased the political edges of their rage and replaced them with the soft patter of silence. hysteria was not the disease; it was the cure for the unmanageable, the unruly. an excision of the political, a sanitization of revolt.

methodological position. demonized, they rewrite theology in reverse. sexually voracious, autonomous, they reclaim the body not as shame but source. wrath, justice, vengeance—not emotions, but epistemologies. the scream is not a symptom, but a syntax. myth becomes manifesto. desire becomes data. their hysterias were not errors but rebellions—madness as resistance, prophecy as rupture. these figures pulse in our veins. they are not history. they are method. they are memory. they are coming back.

III. references: the curse of iconoclasts

Medusa, Cassandra, The Maenads, The Furies, Lilith, Eurydice—each one returns, not as symbol, but as scream. feminine archetypes become hysterical insurgents. they inhabit us, glitch through us. the monstrous feminine, the cursed prophetess: they are not broken—they are breaking. language, order, narrative. silenced, enraged, dismissed by fathers, kings, and doctors. yet they rise, again and again, in archives and dreams. ecstasy, frenzy: their weapons, their truths. refuse to be domesticated! this is not metaphor; it is a

IV. the body: visceral resistance

a body that cannot be read is not a failed text / the archive is also flesh.

constructed as a deviant body, a body out of place, a body out of time, a body that does not submit to the rules of containment. the institutionalization of hysteria is not just medicalized violence; it is the epistemological formation of control itself. hysteria is flesh. hysteria is not mind or spirit; it is the body making itself known when words fail. the body recoils, contorts, erupts, and in its violent rebellion, it refuses to submit to the rituals of compliance. women’s bodies, queer bodies, racialized bodies—these are not just bodies, but the battlegrounds of history. the body that shakes with rage is a body claiming its space in a world that seeks to confine it. the shaking, the twitching, the convulsions—they are the body’s rebellion against the slow death of subjugation. here, the hysterical body is not fragile; it is feral. it is the rupture of norms, the body becoming a site of resistance, a place where power

leaks out in fits and tremors. to be hysterical is to be alive in a world that wishes you dead.

V. language & speech: contagious noise

words were never meant to be silent. the ‘hysterical’ woman, the ‘unruly’ queer—they speak with a voice that is not ‘irrational’ but raw, unfiltered, unapologetic. hysteria is the contagious noise that seeps through the cracks of the language constructed to keep us in line. speech becomes a virus: it infects, it spreads, it resists the neat little boxes assigned to our experiences. when the system tells us to be quiet, to subdue our emotions, our desires, our anger, we speak louder. but our speech is not allowed to be heard. it is called madness, shrillness, hysteria. it is noise, unworthy of the sanctity of the state’s language. the noise of hysteria is the cracking of the facade, the bubbling up of suppressed truth. it is the refusal to be sanitized, the desire to be heard in all our beautiful chaos.

order, their rebellion against unpaid labor a mere emotional aberration. the hysterical woman, the neurotic, the manic—she was the problem, not the system that confined her to domesticity, to silence, to labor that never counted. capitalism and patriarchy, entwined like twin serpents, used hysteria to dismantle any critique that threatened their control. a woman who rages against the system is not revolutionary; she is simply sick. hysteria, then, is the political diagnosis, a way to label dissatisfaction and dismiss it. it is not the anger that needs to be addressed, but the body that dares to express it.

VI. politics: hysteria as political and social oppression

hysteria is not simply a diagnosis; it is a political act, a tool of containment. in the capitalist order, women’s dissatisfaction was always framed as hysteria: a personal failure, a private issue. their anger was pathology, their dissatisfaction a mental dis-

VII. sex: the erotics of madness / orgasmic hysteria

to be hysterical is to be sexual in a world that seeks to control sexuality. pleasure and madness are entangled; hysteria is not just a lack of control—it is the failure to conform to sexual norms. the erotic is bound by the leash of patriarchy, but hysteria is the unshackling of that leash. it is the body that refuses to comply with sexual regulation, the mind that rebels against the control of desire. in the histories of hysteria, we find not just the pathologizing of female desire, but its erotics, its wildness, its refusal to be neatly packaged into the acceptable categories of sexuality. hysteria is the madness of pleasure, the explosion of desire into realms unexplored, untamed. the very act of claiming sexual pleasure is itself a political act—a refusal to be silenced, controlled, contained.

VIII. psychology: mental illness as symptom of the patriarchy

disorder is a weapon when wielded properly

the mind is a battleground. in the realm of psychoanalysis, the diagnosis of hysteria was never about the mind alone—it was about power. the unconscious was a domain, not of personal turmoil, but of patriarchal repression. mental illness, particularly hysteria, is framed as a personal failing, a weakness, a neurotic outburst that has nothing to do with the crushing weight of societal norms. and yet, it is here, in the diagnosis of hysteria, that the patriarchal roots of mental illness are most visible. the symptoms were not just psychological, but political—emotional distress was an understandable response to a world that demanded women to be subjugated. hysteria was the tool used to erase the political roots of mental illness, to make the personal a diagnosis, rather than a form of collective resistance. the mind, too, was colonized, subjected to the rule of reason.

IX. community: reclaimed madness

madness is not the enemy. madness is the revolution’s call. in contemporary feminist movements, madness is not a pathology to be cured, but a badge of honor—a symbol of resistance against the sterilized order of things. reclaiming hysteria is not a retreat into victimhood; it is the forging of a new language, a new way of seeing and being. feminist thought has dug through the wreckage of hysteria to unearth its radical potential, to unearth the rage it represents.

to be hysterical, in this sense, is to be uncontainable, a force of nature that cannot be subdued by any diagnostic framework. intersectional feminism reclaims this madness, recognizing it not as a symptom of weakness but as a revolutionary act of survival, a protest against the structural inequalities that seek to erase us.

X. future: rage as cure & collapse

the future of hysteria is not passive. it is radical, it is alive, it is the possibility of transformation. the future of hysteria is the unshackling of those who have been told their pain is personal, their rage irrational, their bodies disordered. the future sees hysteria not as something to be cured, but as a weapon, a tool of rebellion. it is the spark of revolution in every tremor, every fit, every scream that challenges the status quo. the future of hysteria is not its end but its evolution—into something fierce, untamable, and most of all, unapologetically political. it is the cry that will not be silenced, the body that will not conform. tied between urgency & activism.

from archive to algorithm, and from protest to screen — hysteria is now in the glitch of the ether. a disorder refusing to be coded out.

hysteria is critical affective terrorism. it is the counterforce to all that seeks to govern the body through control, to erase its affective and emotional power through pharmaceutical prescriptions, through institutionalization, through gendered impositions of silence. to be hysterical is not to be broken; it is to be unshackled, to tear through the very membrane that has kept

the radical potential of affect—the heart of political agency—suppressed. it is to speak when others want silence, to move when others want stillness, to reclaim the body when it has been told that it does not have the right to its own existence.

XI. epilogue: hysteria, a site of feminist subversion

hysteria shall become what it was always meant to be: a weapon. not a fragile illness, but a tool of subversion, a flag of revolt. in the ruins of a world built on oppression, hysteria rises as a symbol of feminist power—a refusal to be rendered mute, a defiance against the systems that would keep us in chains. no longer a diagnosis, hysteria is the spark of resistance, the scream of a body that will not be controlled, the voice of a woman who will not be silenced. the hysterical subject is not broken, but whole—a radical force that confronts the world in all its chaos and beauty. it is the revolution that begins in the body, in the mind, in the voice. hysteria is not the end, but the beginning of a new world—one where power is reclaimed, not just resisted.

by Nadia Razali

[Short] feminist

poem on sex

Ultimately, everything still turns around youthankfully it's 2023 and the impassivity which leaves our shoulders cold has started to decrease; not that we haven't lived through that too.

But when you wanted so much for me to come and you did everything to achieve that outcome with consent and care for my desires, that time that I just couldn't -with the small bite high up my inner thighthat time when satisfaction was kept inside my tank without overflowing; everything was ruined because your goal was not accomplished. You told me that it's not feminist to not want to finish [I couldn't] and that this wasn't sex [it was]

I told you that last time with you I had an orgasm [it was true] but I think that something changed in between.

by Myrto Apostolidou

Along with feminism pornography is also on the rise but there's a thing that remains; in the end even my own pleasure is a selfish prescript of theirs and they don't just give because I'm human but rather because I'm a cup reward lottery.

You always know something better than I do about me about my body about my feminism all these musts of yours from which not even a single one did I ever define.

by Prantip

24 Hour Snuff Pornography

£10.99 A Month

Sometimes the television set doesn’t switch off.

Weight Watchers chocolate chip ice cream; calorie counts on your menus; skinny girls frowning in the mirror with an “I look so fat today” dangling from their tongues.

Another woman murdered by her partner.

The boys in the library rating girls from 1 to 10, the greed in their eyes and their hands, the way that I’m too tired to be disgusted.

A lid to stop the spiking. A get home safe message. My ex calling me crazy. Endlessly swiping left or right.

Another woman murdered by her partner.

A changing room exchange of looks.

A lingering feeling of shame flickering in my intestines, like cigarette papers on a flame.

Roe v Wade overturned by the Supreme Court of Justice.

Another woman murdered by her partner.

The violence hidden in summer: scratching an under-bra rash, thighs chafed red, a too-short tank top and stares from middle-aged men when all I want to do is breathe.

But I can’t breathe because

She was thirty-three. She was walking home. He cut her up and put her into a bag when he was done with her.

Buried her in the woods like a dog scraping over its shit.

And my ex didn’t understand why I cried all day, why I’m still crying, why we are all still crying more than a year later.

Anti-acne cream. Anti-ageing cream. Anti-cellulite cream. Sweatshop fashion that gets thrown out after one use. Crossing to the other side of the street at night.

Another woman murdered by her partner.

A TikTok comment calling me a fat pig. A TikTok comment telling me to go hang myself. A TikTok comment begging me for a blowjob.

The way I never felt safe at secondary school. The way that sometimes I still have nightmares.

Boys will be boys and boys will touch me where I don’t want to be touched, boys will tell me they want to rape me and boys will grow up into men and

And?

Another woman murdered by her partner.

by Hannah Corsini

by Annika Hyeonjin Julien

I think that you are vile, but I welcome you to gnaw Feast away at this feast of me and I’ll forget what it is to be raw Feast away at rotting me I beg you! Feast away! Pick at every piece of me You are my sweet decay I want to lay here nothing Not blood, not flesh, not bones I’d love to be here nothing among grass and dirt and stones Can you do that for me? Do you think you can be that for me? How close to nothing do you think that you can make me be?

Summoning Vultures

Hungry, hungry vultures! I lay here newly dead Stop stalking, stop flocking and come peck at me instead I can see that you are peckish Your eyes are bulging black, eating at me from above Your glare is an attack

My belly may be bloated and my skull may be infested, but my heart is ripe and bloody and it wants to be ingested

THE SCREAMING DISEASE

If there are silent diseases creeping up on you, endometriosis is the screaming disease – its symptoms often very painfully present, with people begging to be diagnosed, but just as often overlooked or done away with, accompanied by ‘this is completely normal’ or ‘you are just exaggerating’. This is a very personal account of screaming about my disease and endometriosis may look and feel different for every person.

The first time that I heard about endometriosis was in 2016, when the singer Halsey had just been diagnosed and began to openly talk about this chronic illness. About the years of debilitating pain that had been misdiagnosed, about being called a ‘baby’ for complaining about period pains, about suffering a miscarriage shortly before having to go on stage. One year prior, they had helped me to realise that I was bisexual and while that realisation was immediate, something that I knew to be true from the first moment that the thought crossed my mind, Halsey now made me suspect something that would subsequently take almost a decade to confirm.

In the wake of this first moment that a name was put to an experience that had been following me since I had my first period at age 11, I began plucking away at myself, unfolding parts of myself, metaphorically diving into my cells, membranes, and beyond to start understanding my own body. But it did not need a lot of internal exploration to easily draw conclusions and recognise myself in the symptoms that she spoke about. At this point, I had been on birth control since around 3 months after that first red spotting. Not to control any kind of birth. Not as a form of contraception. Simply to control the thing that usually comes as a sign of no impending birth once every 28 days – that is if your hormones and cycle are as meticulously controlled as mine became after that first gynaecologist visit.

So, with my new knowledge of endometriosis and a hypothesis that could explain 9

years of suffering to accompany me there, I went to my gynaecologist. She was a sweet woman, a kind woman, an older woman, whom I had chosen carefully after going to many different practices and having traumatic experiences. [...] But she was also a woman who was not trained on endometriosis, a relatively ‘new’ area of research in 2016, and she quickly dismissed my hypothesis.

Many ultrasounds, debilitating episodes of pain, and four years later, I was returning from my Master’s degree in London. My latest period before the move had seen me lying on the brightly orange floor of my miniscule en-suite bathroom, incapacitated, writhing in pain, crying in desperation. However, my hopes for diagnosis were higher this time. My previous gynaecologist had retired and the one to have taken over her practice mentioned endometriosis on her website – surely a good sign! At the first chance I could get, I found myself back in the waiting room, nervous and hopeful at the same time. What followed was the same procedure I had already encountered many times before and would continue to encounter many times after. An ultrasound. Nothing of note. Maybe a cyst? Could explain the excruciating pain that immobilised me, especially near my ovaries – not that it was in any way visible now. But not to worry, not to worry, no lasting impact on my health or fertility in any way.

Four further gynaecologists. Four more years. Conversations at parties during which I excitedly exclaimed, “oh, you have endometriosis?”, offending the per-

son across from me with what seemed to be joy at their pain – when it was a misplaced hope of finding my own way to diagnosis through the account of theirs. Four more years of pain, of doubting myself, of thinking myself dramatic, of suddenly developing bouts of fever before my periods, of countless hot water bottles, painkillers, whimpers.