6 minute read

Why Don’t We All Speak The Same Language - Toby Loftus

from Serpentes Issue 6

If the Bible is to be believed, everyone did once speak the same language. However, after constructing a tower in Babylon that glorified their achievements, God punished them by ensuring they all spoke different languages, so that they could never work together again.

To go with a more scientific theory, humans originally communicated in different tongues as a result of long-term geographical separation. We are said to have appeared in Africa about 200,000 years ago, but only developed a capacity for language 50,000 years ago, and so as the first humans dispersed around the globe, different language evolved in different areas. We are genetically wired with primitive forms of communication such as a smile or a laugh, and every language contains the same parts of speech. It’s only the words and their order that distinguish all 6500 which have active speakers today - an impressive figure considering we all have the same vocal apparatus for speech.

Geographical separation dividing up languages is still seen on a reduced scale today. The UK’s official language is English, but the distance between different regions means it has split into many different dialects, and someone with a traditionally Cornish accent may have trouble understanding someone with a typical Glaswegian accent, even though they are supposedly speaking the same language.

But there is still the question of why languages didn’t emerge slightly more similar and interconnected. This is largely due to the contrasting nature of the world, and the popular myth that the Eskimos have 100 words for snow demonstrates the same point. We all have such different daily experiences that it’s not surprising we have dissimilar vocabulary. It could be said that although this is why languages originally differ, it proves no hindrance today against us combining them all into one. But the foremost principle of language is communicating efficiently and articulately, and new unnecessary words prove not much immediate use, and with no sense of immediacy or necessity, a universal language is unlikely to catch on.

Humans have a desire for tribalism, naturally. We like organising ourselves into groups, and by extension, creating walls of communication. It’s this philosophy that led to even more varying dialects for the earlier groups, and still today it’s what counteracts the movement towards a more global way of communication that the internet and long distance travel have brought about. Not everyone wants to lose what makes their background unique, which explains increasing efforts to retain dying languages such as Welsh. So it’s now that we must consider the value of today’s many languages, and whether a modern world would benefit from an artificially constructed universal language. A unified humanity sounds appealing, so why isn’t there such a language already in existence?

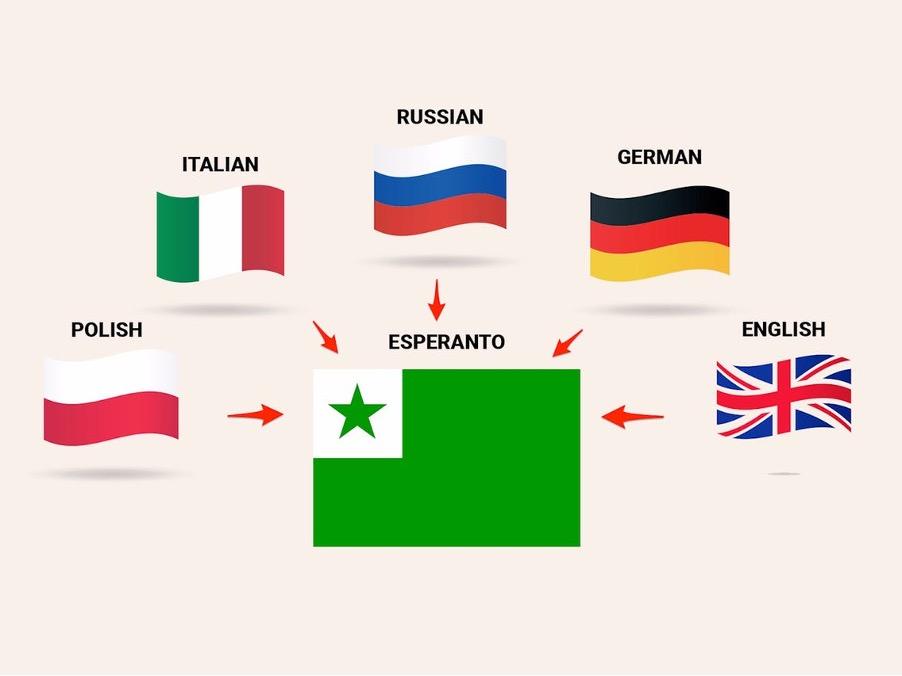

Esperanto is a 19th century attempt to actualise this concept, and was created from a mixture of Romance and Slavic languages, with a goal of serving as the universal second language. But although there have been experiments like this, none of them have been genuinely recognised as the international auxiliary language (one meant for communication between people who don’t share a common first language) as they simply haven’t caught on. So despite Esperanto having an active community of possibly 2 million speakers worldwide with increasing opportunities to learn online, it hasn’t achieved its goal of becoming the universal second language,

and its users are regarded by critics as a ‘stateless diasporic linguistic group’. This essentially means the population of speakers is thinly dispersed and not ruled by a state or government. It offers little hope for the future, because as the founder described himself, no language can survive without a closely supportive community of speakers. These proposals of encouraging the world to speak the same language haven’t worked due to the combined reasons of a suitable language being too difficult to create, and people either being unable or unwilling to learn it. There must be a desire to learn a new language, and currently, no language is perfect or completely regular which is something that appeals to speakers, surprisingly. There is a desire to play with language, which is satisfied by abnormal turns of phrase and peculiarities which give a language character. Idioms and similar verbal oddities that have accumulated over millennia cannot be replicated in an artificially constructed language. There is an absence of history and culture behind an artificial one, and so the appeal of learning it suddenly disappears. We cannot possibly assimilate the world’s 6500 languages, and by extension heritages and values, into one immense universal one, not only because it would be impossible to capture all the detail, but because it wouldn’t be right to concentrate what makes this planet so impressively diverse into one dialect.

Even if everyone agreed with the idea of reducing the number of languages, no one would readily surrender their own, which leads to an impossible situation. So instead, we’re seeing that linguistic diversity is on the increase, and more UK schools encouraging Welsh to be learnt as a second language is an example of diversity being praised in all areas, which for languages such as Esperanto, is a movement in the opposite direction. Finland is a model example of a country with two equal national languages (Swedish and Finnish) whilst Manchester is proud to call itself Britain’s city of languages, with an estimated 200 spoken by long-term residents there. The admirable qualities of multilingualism are widely recognised.

Politically, there is trouble with a universal language, as world leaders in countries like China would be abandoning an important part of their culture in favour of something that would likely have a Latin alphabet resembling European languages, which would consequently become unquestionably dominant. Esperanto speakers were widely persecuted under Stalin and Hitler too. Moreover, an international body inventing a language and demanding that it be taught in schools worldwide would require an immense amount of global cooperation, unexampled in human history. This vast scale of coaction would be implausible if many nations weren’t in favour of the idea anyway.

All in all however, this is about the individual. Just 84% of the world’s adults are literate, and it’s very easy for the developed world to set this giant goal, but many who don’t have access to learning resources cannot be expected to learn a whole new language. Perhaps a new language is unnecessary anyway, because we already have popular solutions in overcoming the language barrier, such as English as an auxiliary language. It’s already used by over half of Europeans in everyday life, with many terms currently adopted by other languages, and a vast architecture of support behind it. New translating technology also renders a universal language slightly more unavailing.

But supposing that despite it all, a perfect international language is created. It’s now that the critical issue is discovered. Language evolves far too quickly for just one. In a few decades, we’d find the language divided up into numerous different ones anyway, because as long as the human population live on different sides of the

Earth, we will not communicate identically. Our language is influenced by culture. Fragments of indigenous slang would slip into ordinary language (as happened in the case of French slang, Verlan, with words appearing in the dictionary) and soon, these different dialects would become separate languages.

There are a number of reasons why we don’t speak the same language overall, and today, a universal one is hindered by the same fallacy that has prevented so many other movements: we cannot create an entirely new start, and hope that the new effort will proceed by its own momentum. Each current language is supported by its native speakers, its history, and the locations where it’s spoken, but for an artificial language, there’s an absence of such a foundation.