6 minute read

Languistic and Change: A brief introduction - Bernardo Mercardo

Language is the primary way humans communicate, whether signed or spoken. It is well-known that it affects the way we view things, from tenses, pronouns and even gender. However, language constantly changes and evolves. There are many factors which cause this, ranging across different fields, including psychology, philosophy and sociology. This is only meant to serve as an introduction into the very many effects, changes, forces and ideas have within semantics and linguistics.

Semantics

Semantics - from Greek (significant). It is the field concerned with meaning. Today, one can search up the etymology of words in nearly all languages from Icelandic to Bengali. Both these languages belong to the Indo-European family, bringing the words back to the theorised Proto-Indo-European. Similarly, you can follow a similar path with other languages outside, revealing other language families - Sino-Tibetan, NigerCongo, Uralic, and many more. This is the simpler way to answer - ‘Why does it mean what it does?’

However, beyond this, why attach specific meanings to certain sounds and the corresponding sequence of signs? This is the more important question within this area. One of the most important effects is the Bouba/Kiki effect. The participant is shown two shapes, one rounded and one jagged, and are asked which shape is ‘Maluma (variant on Bouba)’ and which is ‘Takete (variant for Kiki),’ (Köhler, 1947). Names can vary to an extent but remain phonetically similar. There is a clear preference by participants to name the circle ‘Bouba,’ and the jagged one ‘Kiki,’ chosen by 95-98% of participants (Ramachandran Hubbard, 2001). The results have implications - primarily that the way we assign words with ob jects and meanings is not arbitrary. The causes are not clear, though it is speculated that it has to do with the consonants like /k/ and labial consonants like /b/, and connections between the sensory and motor areas of the brain - also relating to the potential evolutionary origins of language, with its common occurrence even among young children. This arguably represents a close similarity with the condition of synesthesia, where stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway causes involuntary stimulation of another - it is well-known for causing the perception of numbers, letters and days of the week to be coloured. This would further suggest a neurological basis for phonesthesia.

Another similar thing of interest is the word for ‘mum’ and ‘dad’ around the world pronounced ‘mama’ and ‘baba’ in Chinese, mama and tata in Quechua, and mama and papa in Russian too; it is evident that they share huge similarities, and that the word for mum and dad is almost universal even outside of non-Indo-European languages. This is given a cause however, and is attributed to the sounds a baby can first make: m, p and b - and mom from the murmurs during breastfeeding, relating first to food before mother (Jakobson, 1971, p.267).

Sociolinguistics and change

Meanings of words change. Examples are not hard to find - for example, the word ‘awful’ previously meant to be ‘full of awe,’ and the meaning of the word has since changed to have a decidedly negative connotation. The causes behind changes are often complex, and there have been many attempts since the 19th century to organise the way languages change and evolve, and semantic shifts too.

A first example of semantic shift is relevant to the current status of English as the lingua franca of the world - words can experience change by widening or borrowing semantic meaning, like the word ‘star’, which in many languages, expanded to include the English meaning ‘famous/talented person.’

Other examples are more socially and culturally motivated (sociolinguistics). For example, in the realm of queer and LGBTQ+ culture, there are cases of ‘reclaiming’ words - indeed, the word queer was a case of reclaiming. It has meant strange or odd, however, this previously had always come with negative connotations and became a slur for the gay community. The word was reclaimed starting in the late 80s in the spirit of pride and has expanded to mean anyone who is not heterosexual, or as a replacement for the LGBTQ+ label. Similarly, the word lesbian used to mean a woman who was ‘mannish’; however, an activist group called the Lesbian avengers came about in 1992, whose actions involved showy political messages - and as a large movement, were able to change the meaning of the word lesbian. This can also have implications within linguistic theory and philosophy: the usage of queer as a broader term, whether to avoid labels or as a replacement for LGBTQ+, comes into contrast with Russell’s theory of descriptions, words being shorthand descriptions of things - as it is not necessary to know the letters and meanings within the LGBTQ+ acronym. Lesbian too during the time of its semantic shift is a clear example of the importance of context (comparing from 1992 a male politician and an activist saying: ‘Washington D.C.is full of goddamn lesbians’), which is explored in Wittgenstein’s Language-game, likening language to acting (Thorn, 2019).

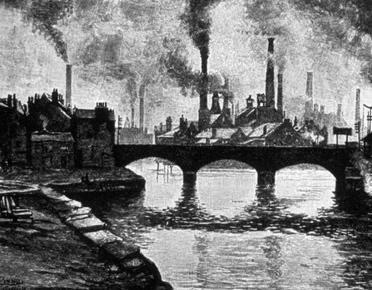

Interesting other cases emerge with the evolution of language - quite clearly the English spoken today is quite different to that spoken in the time of Shakespeare and these shifts continue today with new words being accepted - and with the advent of the Internet and the many communities there, introducing another ‘language game,’ and new contexts, acronyms and words (e.g. whomst, lmao). It is often, and incorrectly, regarded as wrong or subverted, incorrect because through a scientific lens, we cannot say such changes are good or bad. More evolution occurs through distance, and therefore from sociocultural and geographical context - with distance separating Spanish spoken in Spain and Portuguese from Portugal from the other dialects of those languages in Latin America, and certain distinct colours not being present in some languages. The latter has also been organised into levels by Berlin and Kay in Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution (1969) - starting with just dark and light, then red, and progressing through these levels.

Closely linked is African American Vernacular English (AAVE), which has a history of being misunderstood as incorrect English or slang. It is associated with and spoken by black people in America, though most are also bi-dialectal and can ‘codeswitch’ with General American English. Its roots are theorised - however, it is suggested it either originated from Early Modern English - and diverged as slaves brought from Africa would have spoken with each other far more than with other groups, a situation which has changed. However, this remains with American cities as segregated as they still are. This dialect would have been spread all over the country with the events of the Great Migration. The other suggests it was formed from a creole of African languages spoken by those brought over (Yoruba, Igbo, etc.) with English, and continued to be influenced by English. However, it still has its own rules, and is not English ‘with mistakes’. For example, it treats double negatives in a different way, reinforcing the negative, rather than cancelling out (this is a feature shared

in other languages, including in earlier forms of English). It also introduces the habitual be: indicating a habit or something someone might ordinarily do and is why Cookie Monster ‘be eating’ cookies, even if not shown to be (Jackson and Green, 2005). It is this dialect of English that has also backed up racism and the assertion that Black people are less intelligent and contributed to the eugenics debate in the early 20th century - and language, along with socioeconomic factors, were forgotten largely in these studies.

Concluding

In ending this introduction, I should remark that there are still many more regions to discover within linguistics - this has covered social and cultural areas more; however, there are huge amounts of research into grammar and more practical parts of languages as well - and languages remain a crucial component of this, therefore having experience with them too is incredibly useful for communicating over barriers and wider research. And the field will remain of interest, as current political events continue to unfold, and the Internet continues its existence.