32

Health equity feature

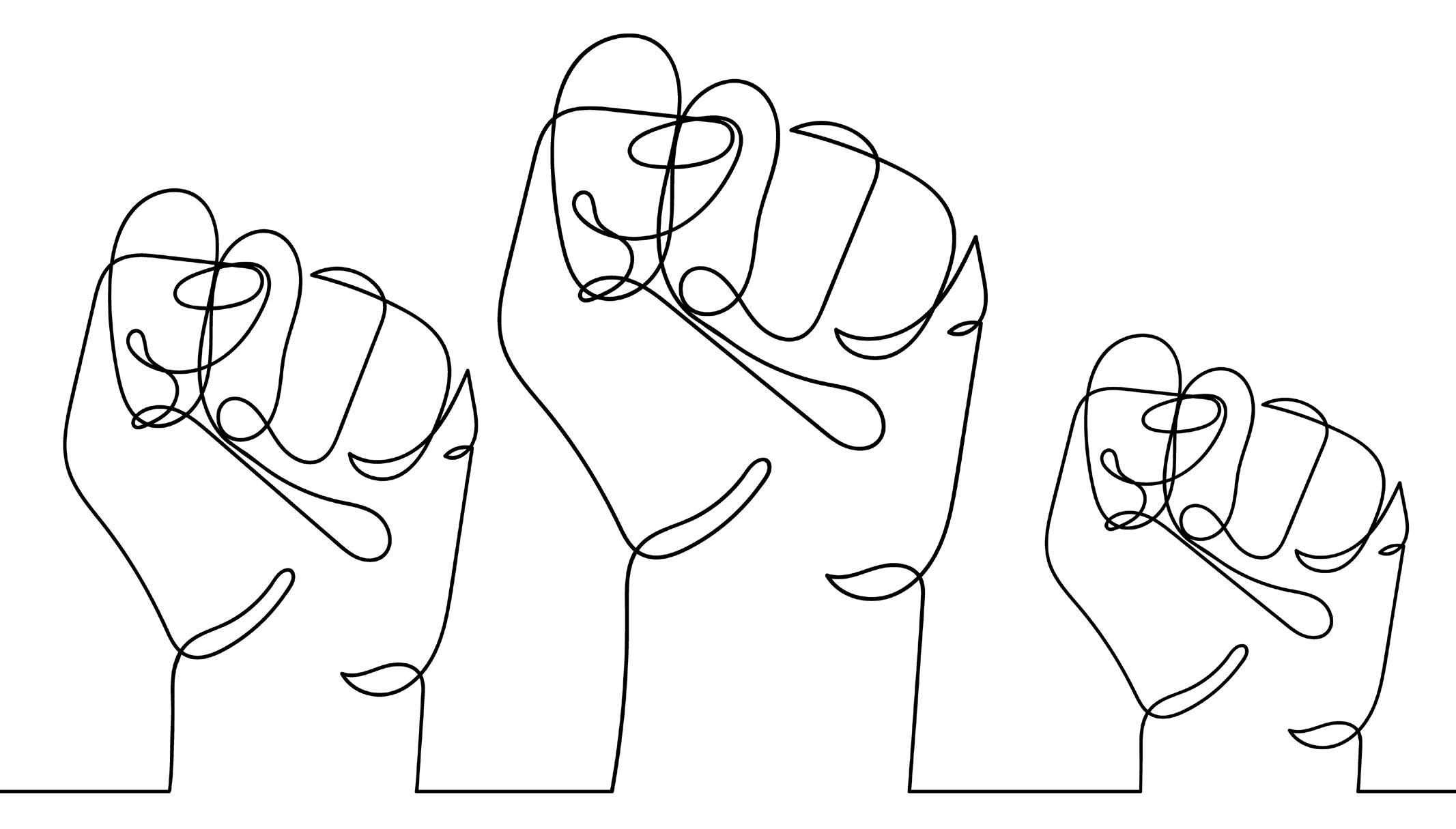

Turning the tide on racism No matter where you live, racism has taken centre stage in 2020. The Black Lives Matter protests and COVID-19 pandemic have shone a spotlight on racial injustice around the world. On May 25, George Floyd, an AfricanAmerican man, died after being handcuffed and pinned to the ground by a White police officer’s knee. The tragedy, captured on video, sparked large protests against police brutality and systemic racism across the United States (US). The rallies triggered a global resurgence of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag on social media. In Australia and New Zealand, news feeds on Facebook and Instagram turned black and thousands of people marched the streets. The message was clear: Black people are tired of being silenced, abused and dehumanised. At the same time, the spread of COVID-19 triggered new displays of xenophobia. As some politicians chose to describe COVID-19 as the ‘China virus’, racism took off. In a Sydney cafe, a blackboard read: ‘Coronavirus won’t last long because it was made in China.’ It was the tip of the iceberg. Soon enough, people of Asian descent were reportedly being verbally abused and spat on. Healthcare workers were among them. The Australasian College for Emergency Medicine reported a marked increase in racial abuse towards hospital staff, with patients refusing to be treated by some health professionals. In February, Queensland general surgeon Dr Rhea Liang encountered a patient who refused to shake her hand (this was before social distancing). “This is not sensible public health precautions,” she wrote on Twitter after the incident. “This is racism.” Unsurprisingly, the Australian Human Rights Commission recorded a surge in racial discrimination complaints.1 The allegations involved everything from verbal abuse and exclusion from public establishments to physical violence. The pandemic also highlighted health inequalities. As the virus took hold in the US and the United Kingdom (UK), health authorities quickly noticed that people

from racial and ethnic minorities were at increased risk of getting COVID-19 and experiencing severe illness and death. In the US, African Americans have died from the disease at almost three times the rate of White people,2 and in the UK, Black and minority ethnic groups have suffered twice the death rates of White people.3 The trend has prompted new discussions about social determinants of health and structural racism across the world. While New Zealand’s public health measures have protected many of its citizens so far, researchers have predicted that the risk of dying from COVID-19 is at least 50 per cent higher for Māori people than New Zealanders from European backgrounds. This is partly due to higher rates of existing health conditions such as heart and lung diseases, which are strongly associated with more severe outcomes from COVID-19. Similar risk factors put Indigenous Australians at high risk, too.4 But there are other factors that increase the risk of getting infected for Māori and Pacific people. Research from the UK shows that people who live in large households, or in poorer areas, are at greater risk of being infected. About 25 per cent of Māori and 45 per cent of Pacific people live in crowded housing.5 They are also more likely to work in jobs or workplaces with higher health risks, including of infection.6 Māori and Pacific people also experience greater rates of unmet healthcare need and greater levels of poverty, which have been shown to have a significant effect on fatality rates from COVID-19.7 Writing in The Conversation, the researchers who created the modelling said COVID-19 ‘has potential to intensify existing social inequities that result from colonisation and systemic racism.’8 The perfect storm of such factors has been seen in the US where many African Americans are essential workers, such as cashiers, bus drivers or hospital assistants – jobs that increase the chance of exposure to COVID-19. In addition, many predominantly Black

neighbourhoods experience problems such as food insecurity and industrial

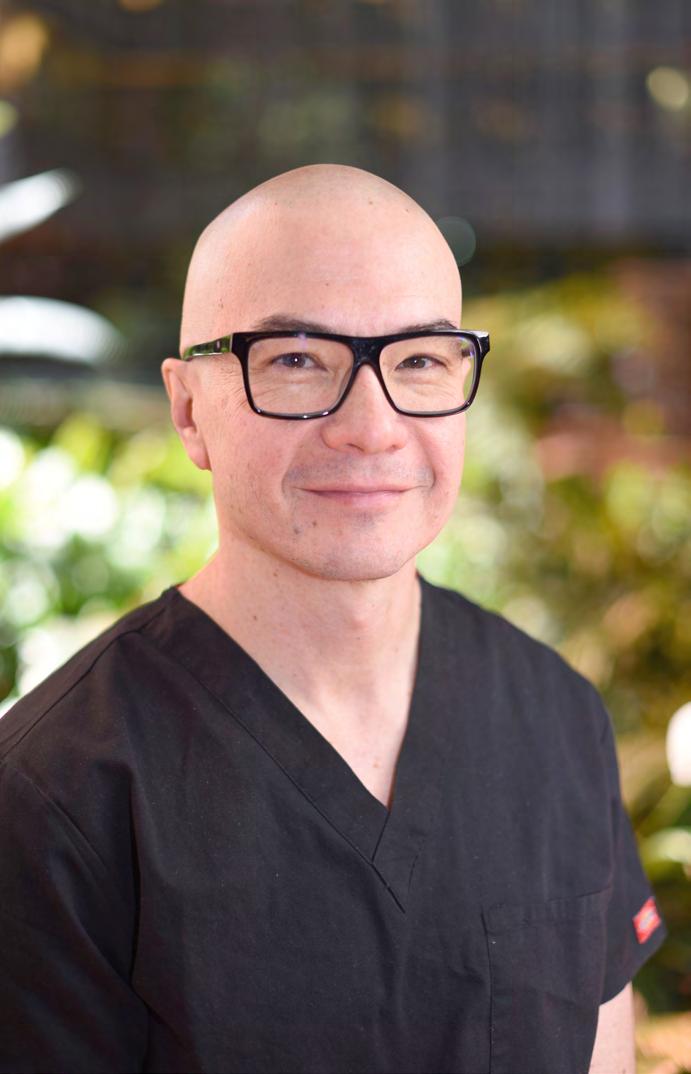

pollution, leading to higher rates of conditions such as diabetes and lung diseases, which are COVID-19 risk factors. Then there is the issue of access to health care and money to pay for preventative care as well as treatment such as oxygen when being discharged from hospital. These problems are not new for surgeons, especially those involved in the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons’ (RACS) Indigenous Health Committee (IHC), which focuses on ways to achieve health equity for Aboriginal, Torres Strait Island and Māori people. The committee’s efforts include campaigning for funding to reduce the burden of diseases prevalent in these communities through more prevention, screening and treatment. The committee has also looked at factors that reduce access to health care among Indigenous people, such as the impact of previous trauma experienced in health services. In 2019, RACS introduced a new requirement for surgeons to improve their cultural competence and cultural safety knowledge. The College recognised that the significance of health inequities on poor health outcomes – particularly Indigenous peoples in Australia and Māori in New Zealand – was not adequately reflected within the competency framework. The new addition requires surgeons to demonstrate a willingness to embrace diversity among all patients, families, carers and the healthcare team and respect the values, beliefs and traditions of individual cultural backgrounds different to their own. RACS is also aware of racial discrimination against Trainees, Fellows and Specialist International Medical Graduates. In 2015, a survey commissioned by the College found that one in five had experienced discrimination and some of it was racial.9 In response, RACS launched Let’s Operate with Respect – a campaign to help reduce discrimination, bullying and sexual