26

Giving back feature

A hero of surgery: Dr John Hargrave Australia lost a hero in August. A surgeon who made it his life’s work to eradicate leprosy in the Northern Territory. A gifted educator who shared his vast medical knowledge with health workers and Aboriginal people, and a doctor of unparalleled humility and generosity. Dr John Hargrave has been called a surgical pioneer, a living legend, an icon of surgery and ‘a living saint’. But when he was alive, his friends say he would have none of that. He never spoke about being appointed a Member of the British Empire in 1967, or about becoming an Officer of the Order of Australia in 1995. There was also an Honorary Doctorate from Charles Darwin University, the ANZAC Peace Prize in 1996, the ESR Hughes Award in 1999, and the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) International Medal in 2007, but he was happiest when the attention was on other people. Dr Hargrave died in Hobart on 6 August 2020. He was 89 years old. He never married or had children, but he had thousands of friends. Among them were many Aboriginal people whose languages he’d learnt so he could converse with them. He’d trained hundreds of Aboriginal people as Indigenous health workers so

they could care for patients in the East Arm Leprosarium and within their own communities. Born in Perth, Dr Hargrave studied medicine in South Australia before doing his internship in Perth. In 1955, he was appointed Survey Medical Officer in the Northern Territory. Then, in 1957, he was the medical officer with a patrol of government officials visiting Lake Mackay in search of the last groups of nomadic Pintubi people of the Western Desert – Indigenous Australians who had never had any contact with white colonists. When they found the Pintubi people, Dr Hargrave examined many of them individually and reported that they were “in excellent condition; well-built, well-nourished and healthy.”1 Further, he recommended that “they be left entirely alone” and “be protected from white people, as this inevitably leads to their contracting diseases foreign to them”. During his work in the Northern Territory, Dr Hargrave noted that leprosy was a significant health issue. It had been brought into the Territory in the 1880s by gold miners and labourers, and had spread disproportionately into Aboriginal communities. Leprosy patients, including children as young as four years of age, were forcibly removed from their families and incarcerated, usually for the rest of their lives, first on Mud Island then on Channel Island in the Darwin Harbour. In 1956, the East Arm Leprosarium on the mainland replaced the island leprosarium. Dr Hargrave became its medical superintendent and he brought a respectful, collaborative approach to the care of Aboriginal patients, who had grown afraid of Commonwealth institutional powers. They were so fearful that they would often hide their leprosy symptoms to avoid being separated from their families.

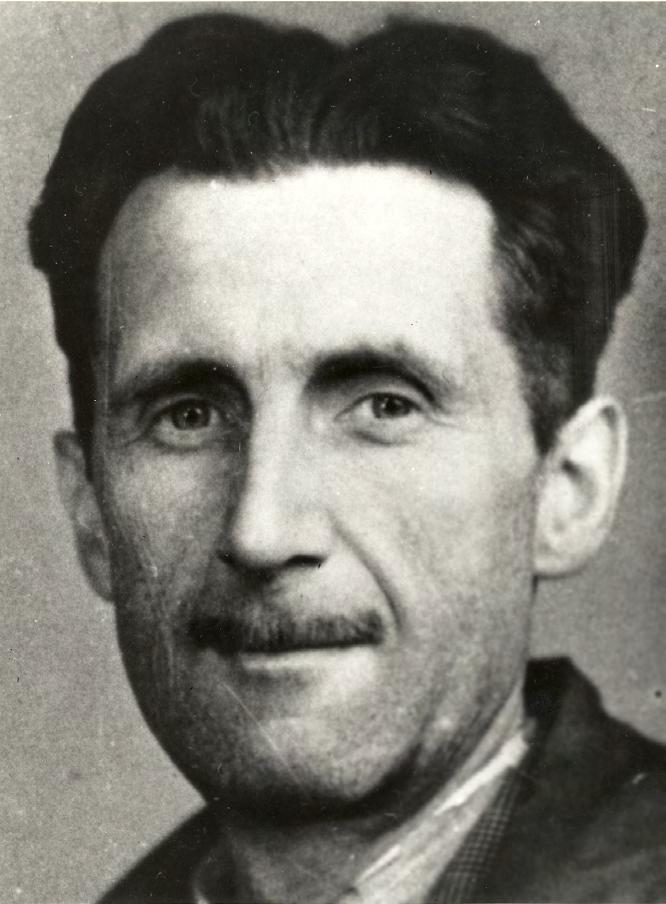

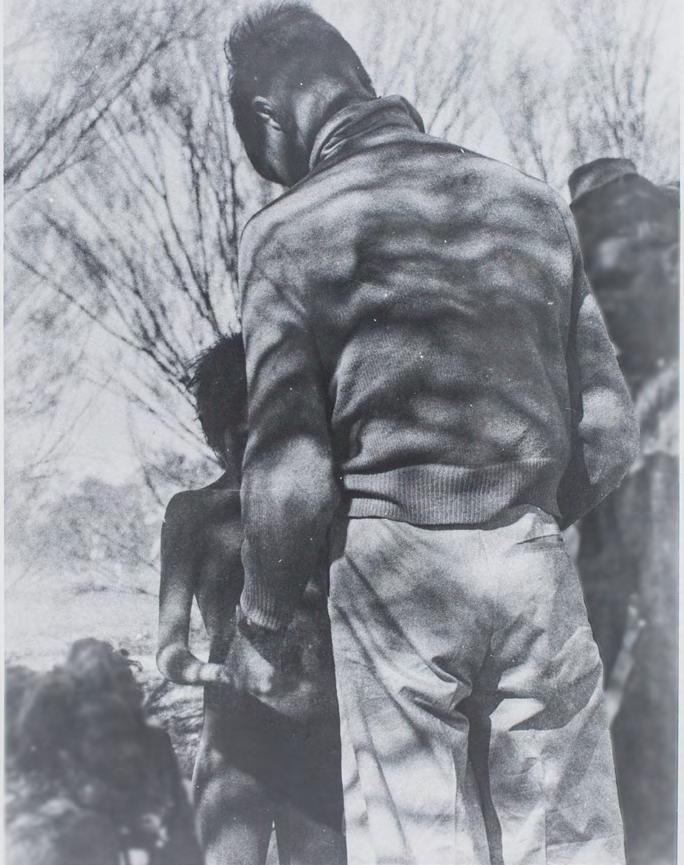

Dr John Hargrave at Lake Mackay, 1957

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised the following content contains images of deceased persons.

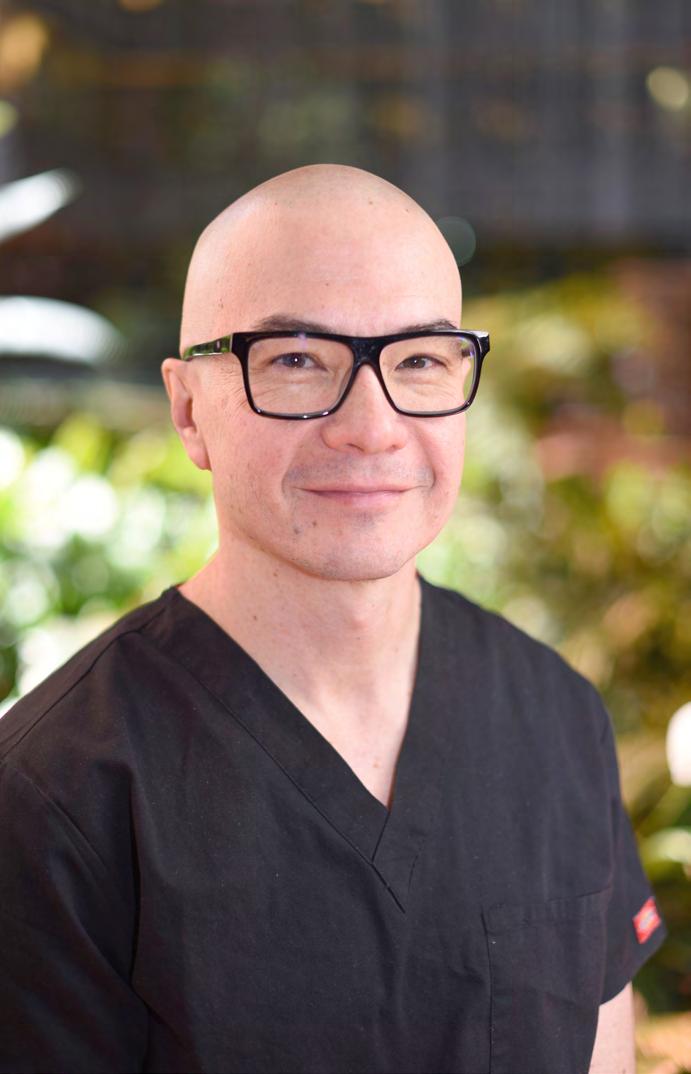

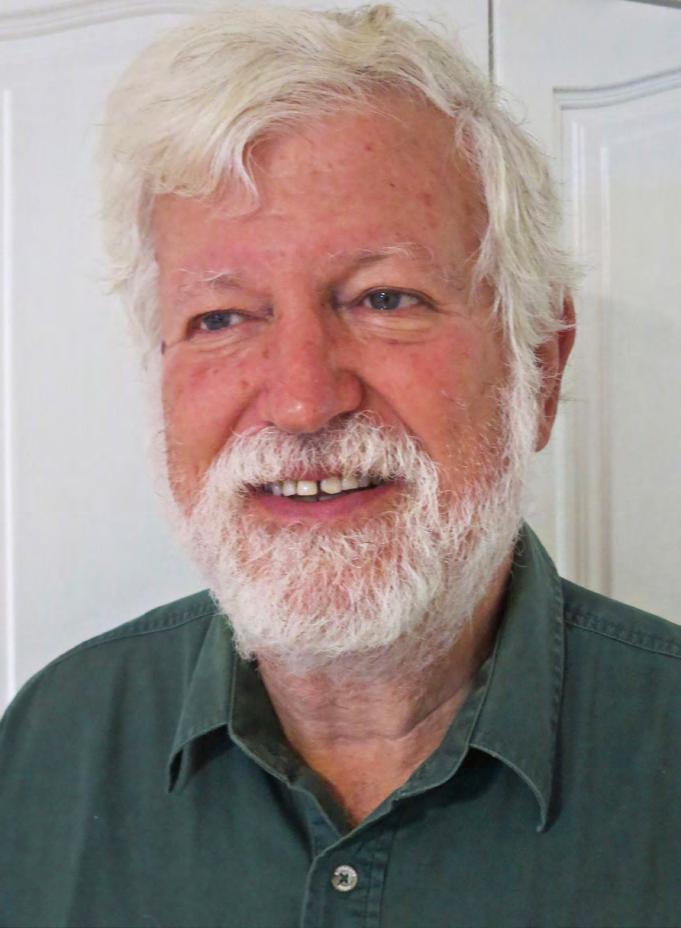

Dr Hargrave’s warmth and sincerity helped him gain the trust of his patients

Dr John Hargrave in East Timor

and their families. With assistance from the Catholic sisters from the Order of Daughters of the Sacred Heart, who worked with him in East Arm Leprosarium, more people were diagnosed and treated. He established a leprosy register, set up an operating theatre and formalised the training program for Aboriginal health workers. He also got a pilot’s licence, so he could fly throughout the Northern Territory to attend to his patients. At some point, however, Dr Hargrave realised it wasn’t enough. More would be required if the East Arm Leprosarium was to offer world-class leprosy treatment. Dr Hargrave visited leprosy centres throughout South-East Asia and, with the assistance of a World Health Organization scholarship, he travelled to India and worked alongside Dr Paul Brand, the pioneer of muscle tendon transplant. For several months he stayed and learnt how to transplant tendons to correct foot drop, restore movement in fingers and thumbs, and perform other reconstructive surgeries for deformities resulting from nerve damage. On his return to the Northern Territory, Dr Hargrave established a reconstructive surgery program at the East Arm Leprosarium, and implemented a