G un t a

Bauhaus Masters

Bauhaus 1919 to 2023

Radical Innovations in design education

Editors: James Volks and Susan Harrrison

Bauhaus 1919 to 2023

Editors: James Volks and Susan Harrrison

The Bauhaus was a prolific design school which ran from 1919-1932. The core principle of the school was to question and challenge the fundamentals of design practices which had been accepted for many years. It aimed to create a sort of utopian craft guild that represented the unity of art amongst all crafts. It created a ‘renaissance’ of sorts in the world of design-bringing forward new and interesting practices to achieve innovative and unique creations. The Bauhaus was headed by a group of designers referred to as the ‘masters’. These were designers at the top of their field, striving to teach fellow creatives to excel in their work and inspiring them to further their studies through the experimentation and play of their craft. The masters held major influence in the school- some of the most well-known masters included Paul Klee, Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer. They taught classes and ran workshops within the Bauhaus, spreading their knowledge and training young people for professions that essentially did not exist before the Bauhaus years. These workshops saw not only the production of new industrial designs for furniture, metal, textiles and modern printed materials but, at the same time, the formulation of new training courses and the preparation of new professions which would operate at the interface of design and technology in the widest possible sense. Throughout this book, I will focus on the master of the textile workshop Gunta Stolzl. Stolzl was an outlier among masters, being the first woman master to be appointed. She was a talented designer and textile artist and earned her role

in a school with an unfortunate gender-bias. I felt it was important for her to be the focus of the book, as she stands out due to her drive and leadership qualities along with her obvious creative talents. This book will begin with a more in-depth discussion of the context surrounding the Bauhaus. I will look at the history of the Bauhaus, the ‘Bauhaus Style’ and the influence of the masters within the institution-the classes they taught and the houses they lived in on the campus. I will then begin to discuss Stolzl’s early life followed by her contributions within the school. I will examine the work she produced during her time in the Bauhaus, briefly touching on the segregation and gender inequality that occasionally overshadowed the acknowledgement and recognition she received for her work. The book will end with an article extracted and translated from the journal ‘Bauhaus’, where Stolzl discusses the development of the weaving workshop. This piece is particularly impactful as we gain a first-hand insight into her thoughts regarding her practice. As a graphic design student, I was aware of the Bauhaus before researching this book. I knew of the impact that the school had made in the modern design space and some of the trends that they pioneered. However, I was not aware of the masters that made all of this innovation possible, especially the women. Overall, the aim of this book is to delve into the principles of the Bauhaus while giving recognition to the masters who started it all, especially masters like Stolzl, who perhaps to this day, are not fully credited for their contributions.

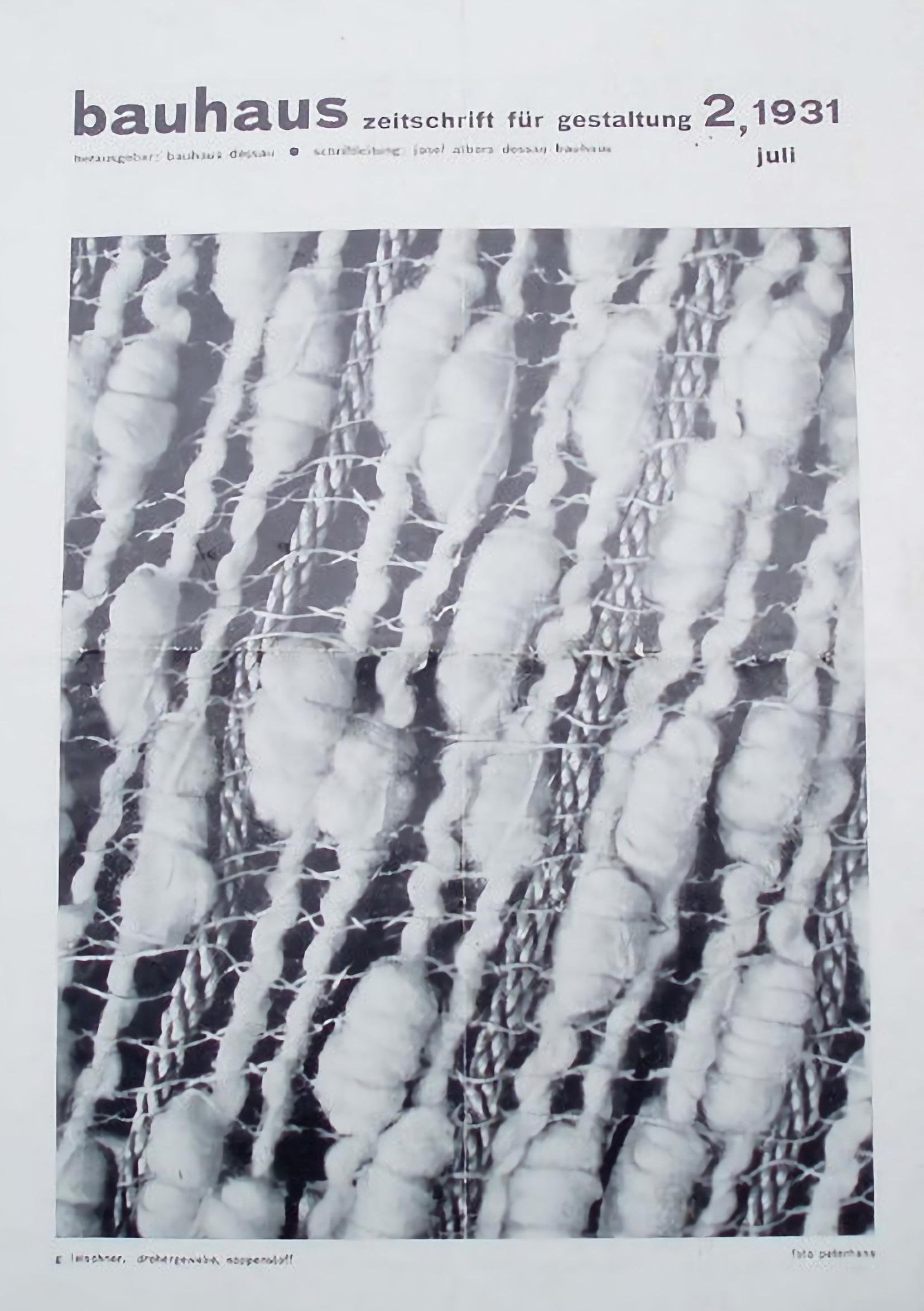

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 in the city of Weimer by German architect Walter Gropius. The focus of the school was to reimagine the material world to reflect the unity of all the arts. It aimed to create a utopian craft guild combining architecture, sculpture, and painting into a single creative expression. Leah Dickerman wrote in Bauhaus Fundamentals, “the Bauhaus brought together a diverse group of international artists, designers and architects in a kind of culture think tank for the times”. It was the place where many prolific design methods were created and explored. For example, the method of minimalism was created in the Bauhaus. Teachings at the Bauhaus focused on reducing the materials used and keeping the design functional. The mantra “form follows function” was widespread in the school. This led to the trend of minimalism both in product design and architecture throughout Germany and the United States of America. The ‘bauhaus’ journal was established to get these new ideas out to the general public and spread the word about the work they were doing. It contained information about the Bauhaus, its latest products and commissions, and welcomed contributions from guest authors. At the beginning almost every issue was devoted to a particular theme: the first number (edited by Gropius, designed by Moholy-Nagy) briefly introduced all the workshops, while issue 1927/3 was compiled by Schlemmer and dedicated to theatre. The journal served as a good record of the trends the Bauhaus were both following

The Bauhaus was opened in Weimer, Germany in 1919 shortly after WW1 ended. At the time Germany was at a crossroads. They were having to adapt to changing governing structures and there was an heir of uncertainty over leadership status. The country was on the brink of creating a new republic. The Bauhaus became one of the spaces where new cultural ideas could brew. They shared their manifesto to the country, attracting creative students with unique ideas. The school was exposed to political pressure due to the change they represented. This was apparent in 1925 and led to many masters leaving the institution. The Weimar Masters had terminated their contracts before considering the future options. The Bauhaus simply needed to relocate. The move could easily have spelled the end of the Bauhaus. But the fame of this new type of school proved such that, in the

course of the next few months, a number of cities expressed interest in giving the Bauhaus a home. From Dessau, Frankfurt/Main, Mannheim, Munich, Darmstadt, Krefeld and Hamburg. Ultimately, however, the only offer of substance was to come from Dessau, a city governed by the Social Democrats and whose mayor, Fritz Hesse, expressed his personal support for the Bauhaus. The body of Masters agreed to the move, and what had been a state school now became a municipal institution. Gropius was the head of the Bauhaus in Dessau for three years. During this period the school reached another pinnacle in its career. However, the school continued to face political pressure and in 1932 they relocated again to Berlin. Eventually the school closed its doors in 1933, amidst the political turbulance of Nazi Germany who believed the Bauhaus to be a centre for communist thought.

Over the course of the Dessau period the individual teachers developed and, in some cases, fundamentally revised the content of their teaching. From the students point of view, courses were more intensive and more demanding. At the core of the preliminary training given to Bauhaus students lay Josef Albers. Albers, a former elementary-school teacher, came to the Bauhaus hoping to become a painter. Having completed Itten’s Vorkurs he joined the stained-glass workshop, whose poor record in commissions was soon to cost it its independence. As from autumn 1923 Albers taught the first semester of the Vorkurs, consisting of 18 lessons a week, while Moholy taught the second semester (8 lessons a week). Albers’ timetable included visits to craftsmen and factories. Without machines, and using the simplest, most conventional tools, pupils designed containers, toys and small utensils, at first using just one material and later in combinations. In this way students familiarized themselves with the inherent properties of each material and the basic rules of design. Although Albers naturally adopted some elements - such as the study of materials - from Itten’s Vorkurs, he systemized them in a completely new way, as can be seen in his approach to material studies. From 1927 onwards students were no longer permitted to work with materials at random, but instead had to progress through glass, paper and metal in strict order. They worked solely with glass in the first month and paper in the second, while in the third month they were allowed to use two materials which their studies had shown to be related. Not until the fourth month were students free to choose their own materials. Albers observed: “Materials must be worked in such a way that there is no wastage: the chief principle is economy. The final form arises from the tensions of cut and folded material.” Albers’ teaching had a particular and profound influence on many students and

Municipal funding had also allowed Gropius to build a group of Masters’ houses in a small pinewood within walking distance of the new Bauhaus building. These consisted of three pairs of semi-detached houses with studios, each for two professors, and one detached house for himself. The ground-plans of these mirror-image semi-detached houses met at a 90° angle to each other and thus served to illustrate Gropius’ concept of the ‘large-scale building set’, even though it was not possible to use prefabricated elements in their construction. The houses, which the Masters rented from the municipal authorities, were furnished with remarkable generosity, astounding even the artists. Schlemmer wrote: “I was shocked when I saw the houses! I could imagine the homeless standing here one day watching the haughty artists sunning themselves on the roofs of their villas.” Klee later complained about the size of his heating bills, and he and Kandinsky sought to obtain a rent rebate from the municipal authorities. Some of the artists supplied their own interior colour schemes. Klee had his studio painted yellow and black; Kandinsky chose a rather eccentric decoration scheme, and even Muche experimented with colourful mural designs. Muche’s bedroom was painted to a scheme by Breuer. A contemporary visitor described the artists’ estate thus, “Everywhere the same purposeful horizontals, the same flat roofs and incisive straight lines of the frameless doors and windows, repeatedly surpassed by the glass wall of a studio. A living-machine objectively whose coldly uniform essence nevertheless incorporates, as on artistic component, the attractive play of light and shadow set in motion by the not yet grubbed trees.”

Gropius’ house was destroyed in the Second World War. The remaining houses were preserved, but have been drastically altered and are now in poor condition. on reducing the materials used and keeping the design functional.

Fig 2.1: Potrait of Stolzl 1919

Fig 2.1: Potrait of Stolzl 1919

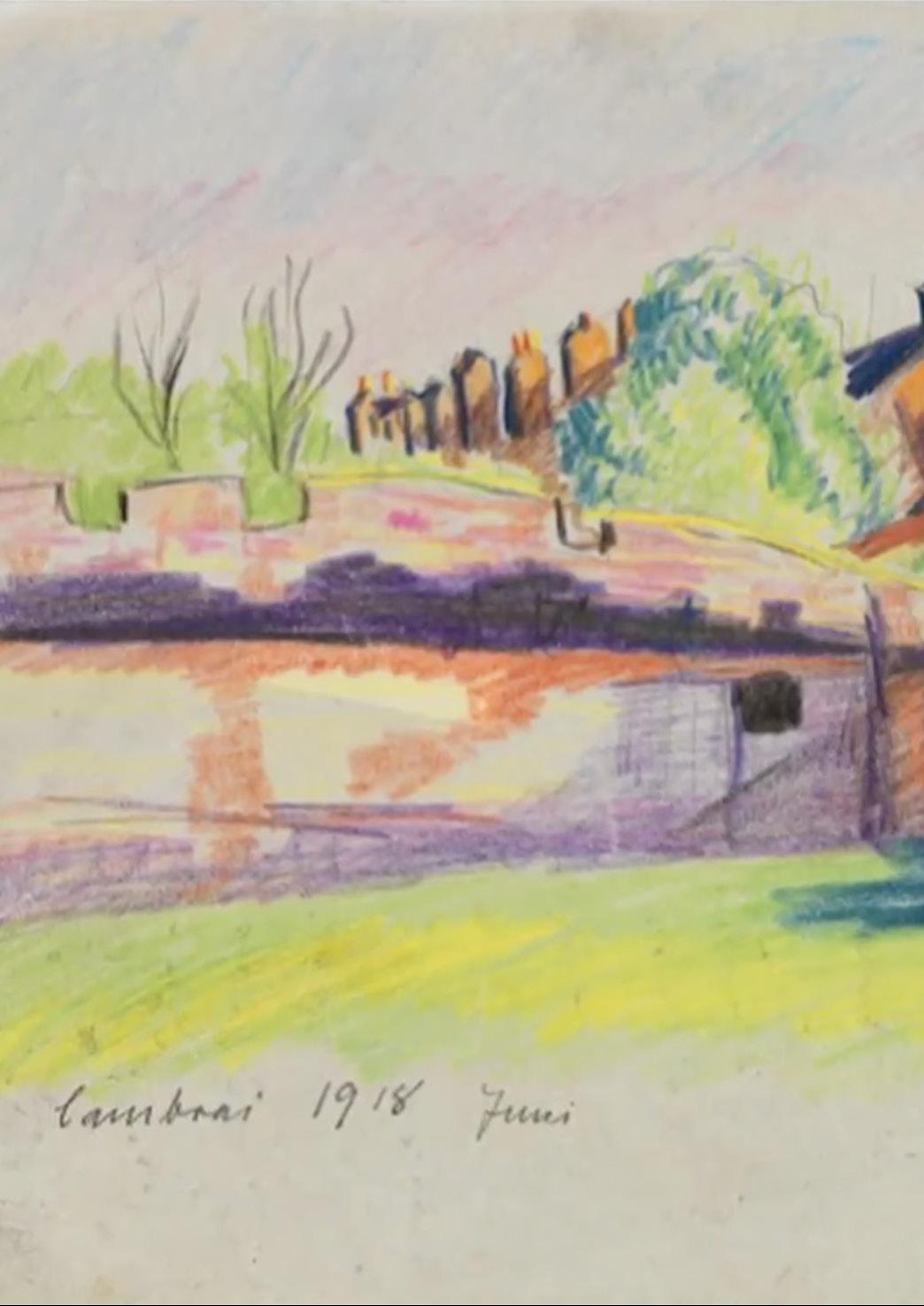

Gunta Stolzl was born on March 5th, 1987, in Munich Germany as Adelgunde Stolzl. She kept diaries from 1911 onward with entries about friendships, mountaineering and discussions of novels and philosophical readings. Her father, teacher and school director, recognised and furthered her talents. She always had a keen interest in creating visual arts and as a result, she studied ceramics and art history in the School of Arts and Crafts from 1913-1916. She made hundred of sketches of architecture, potraits and landscapes during her time at the school. She then served as a voluntary Red Cross nurse from 1917-1918 during the First World War. She served alongside her only brother till the end of the war and during this time she made many sketches. After this, she wanted to get back into the creative field to study and practice art, so she decided to return to the School of Arts and Crafts. While there, she began to reform their curriculm and this is when she first came into contact with the Bauhaus manifesto. She applied to the college immediately with a portfolio that was absent of any craft and was instead focused on paintings and pencil and charcoal sketching. Her work in this portfolio was all 2D and could not foresee the gifted textile designer she would become. She died on April 22nd, 1983, in Zurich Switzerland. She was survived by two daughters, Monika and Yael and their respective children. Her daughters spread her story through the creation of her website along with a biography they produced detailing her achievements. They also deliver talks about her life and work.

Fig 2.2: Portfolio Piece Submitted As Part of Bauhaus Application

Fig 2.2: Portfolio Piece Submitted As Part of Bauhaus Application

1919

She joined the Bauhaus. She was attracted to study there as it was home to visual artists such as the painters; Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

1927

She became a master. The workshop thrived under her leadership and she was regarded as the ‘financial backbone’ of the Bauhaus.

1931

She resigned due to political pressures. She married a Jewish man and became a target for the Nazis. A swastika was drawn on her door.

“The Bauhaus period was, for all of us, like a chamber of unalienable pleasures.”

- Gunta Stolzl

Gropius opened the school with the promise to admit “any person of good repute, regardless of age or sex”. This made the Bauhaus an attractive opportunity for women who had previously been denied access to schools with such creative allure. As a result, when the Bauhaus opened, its student population was predominately female. As time went on, the leaders of the Bauhaus began to worry about the number of women enrolled. They were of the opinion that the women were not up to the academic rigor of the school and would “dilute” the creative output. Gropius in particular was “worried that the presence of so many women would give the institution an amateur affectation, infecting the atmosphere with something reminiscent of the arts and crafts movement that he was keen to avoid.” As a result, Gropius took away the women’s right to choose their artistic disciplines like the men could. Instead placing them all into the weaving department which later became known as the ‘women’s department.’ This was viewed as a better match for their abilities. A strong gender-bias was now engrained in the structure of the school and became an element of the internal culture.

This newly created divide led to a segregation of what was perceived as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine arts’ within the Bauhaus. Weaving was believed to be the only acceptable creative path for a woman, this perception is captured in a quote by Oscar Schlemmer “where there is wool, there is a woman who weaves if only to pass the time.” Gunta Stolzl herself did an interview with the Bauhaus Journal ‘Offset’, in 1926, and is quoted saying “weaving is primarily a woman's field of work. The play with form and colour, an enhanced sensitivity to material, the capacity of adaptation, rhythmical rather than logical thinking - are frequent female traits of character stimulating women to creative activity in the field of textiles.” This quote is very telling as her internal degradation comes to light. She suggests that women are incapable of logical thinking and instead strive while completing repetitive, menial tasks. Misogyny and prejudice did not just affect the recognition of Stolzl’s work but it also had a direct impact on her day-to-day life. After Stolzl gave birth to her first daughter, Yael, she felt the full capability of inequality in the

Stolzl was known to apply ideas from modern art into weaving. It was through this combination of ancient form with contemporary ideas that her best work was produced. She was of course a part of the Bauhaus Movement and her pieces were said to typify the ‘Bauhaus Style’. She created abstract, unique and innovative textiles. There was a freedom in her work and she experimented with synthethic materials. These materials were sometimes unorthodox such as the work she did with cellophane, fiberglass and metal. She is quoted saying “there is no ‘must’ in art, because art is free”. She was an artist who was willing to take risks. A piece of hers that is particularly striking and clearly displays her style is her piece ‘Slit Tapestry’. Within this piece we see how she implements the Bauhaus movement into her work. It is composed of cotton, silk and linen and illustrates a colourful and dynamic landscape, similar to the ones Stolzl drew in her youth. She brings forward her early work in this piece, combining it with the expertise she accumulated in the Bauhaus.

As well as being experimental, her work was also very colourful. She used a wideranging colour palette and tested different colour combinations throughout her work. The pieces displayed on the right-hand side show a more subtle colour approach, and we can see her flexibility and willingness to discover what works here. This fabric that she created is also asymmetric, which was another common characteristic of her work and can be seen in the majority of her pieces.

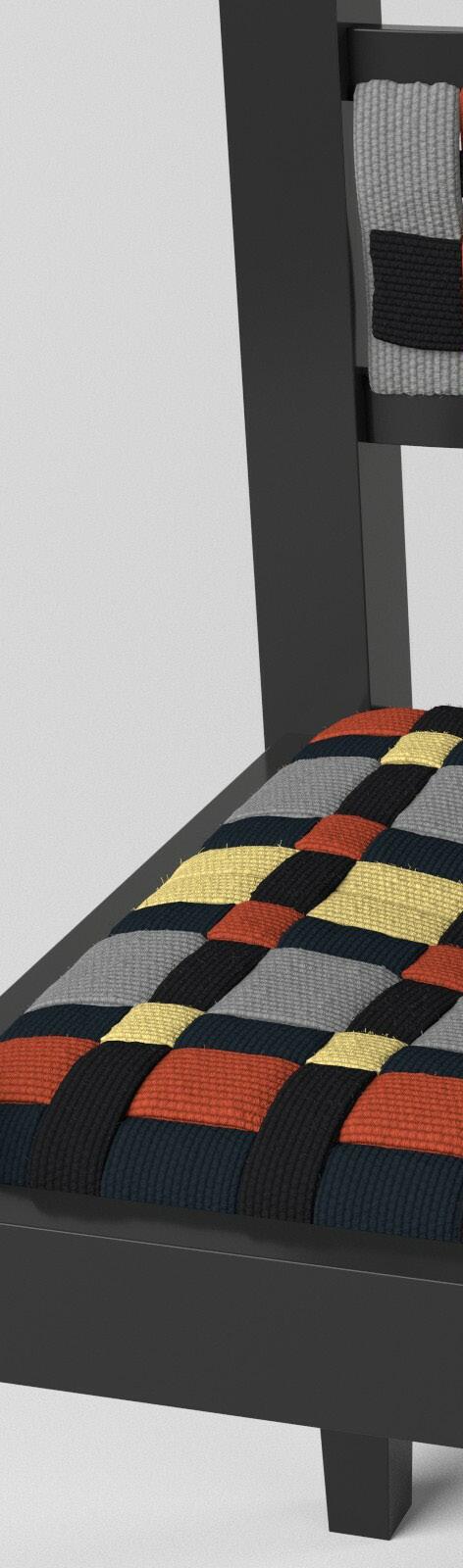

This chair is called the Colorful Weave Chair and can be seen on the Bauhaus 100 site. It was produced by both Marcel Breuer and Gunta Stolzl, combining his expert knowledge on chair design with her impressive textile work. On the seat and on the back of the chair, Stolzl employed taut strips of woven upholestry which were to characterise so much of Breuer’s later work. This piece is a beautiful, individualistic piece of furniture. It uses brightly coloured geometric patterns. It was extremely successful and lead to repeated collaborations between the pair throughout their respective careers. Another famed piece of theirs was the African chair which was recovered in 2004.

Fig 5.3: The cover of the ‘bauhaus’ journal in 1931 when Stolzl’s article was published

Fig 5.3: The cover of the ‘bauhaus’ journal in 1931 when Stolzl’s article was published

The transfer to Dessau brought the weaving workshop, as well as all the other workshops and departments, new and healthier conditions. We were able to acquire the most varied loom systems (Kontermarsch, shaft machine, Jacquard loom, carpet-knotting frame) and in addition our own dyeing facilities. The aim of the general education was to loosen up the student and to provide him with the broadest possible base and with a direction for a systematic approach to his work.

From now on, there begins a clear and final distinction between two areas of education that initially were fused with each other: The development of functional textiles for use in interiors (prototypes for industry) and speculative experimentation with materials, form, and colour in tapestries and rugs. Functional textiles are necessarily subject to accurate technical, and limited, but nevertheless variable design requirements. The technical specifications, resistance to wear and tear, flexibility, elasticity, permeability or impermeability to light, fastness to colour and light, etc., were dealt with systematically according to the final use of the material.

The aesthetic qualifications, the demand for beauty, the effect of woven fabrics in a room and the feel of it, are much more difficult to define objectively. Whether lustrous or flat, whether soft or severe, whether strong or subdued in texture, whether coloured brightly or softly, all this depends on the kind of room, its functions, and not least of all on individual needs. The tool of the weaver, the material, colour,

and the weave - are subject to constant technical improvement. Wool, silk, cotton, the synthetic fibers (cellophane) are continuously being improved by better breeding and cultivating methods, mechanical treatment (process of spinning, refinement), new scientific inventions, and by new dyeing methods. The vitality of the material forces people working with textiles to try out new things daily, to readjust time and again, to live with their subject, to intensify it, to climb from experience to experience in order to do justice to the needs of our time . Experience shows that we are advancing along useful paths: The cultural influence of our work on the textile industry and on other workshops is clearly in evidence today. Those who have been trained by us are now occupying top positions in mechanical weaving mills and workshops and also in schools.

Only active participation in solving the changing problems of life and home makes it possible to keep the educational and cultural work of the Bauhaus weaving workshop vital and progressive. Woven fabrics in a room are equally important in the larger entity of architecture as the colour of the walls, the furniture and household equipment. They have to serve their purposes, have to be integrated, and have to fulfil with ultimate precision the requirements we place on colour, material, and texture. The possibilities are unlimited. Understanding of and feeling for the artistic problems of architecture will show us the right way.

Bunting, G. ‘Frauhaus: The Women of the Bauhaus’ - Modus. Accessed 24 January 2023.

Cogley, B. ‘Textiles by artists Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl revived for Bauhaus’ 100th anniversary’. Accessed 23 January 2023.

Griffith Winton, A. ‘The Bauhaus, 1919-1933.’ Accessed 25 January 2023.

Invaluable ‘How Bauhaus Art Radically Changed the Modern Landscape’ 20 March. Accessed 27 January 2023.

Skender, M. ‘History of textile art: Gunta Stölzl’ (1897-1983). Accessed 24 January 2023.

Stone, C. ‘The Bauhaus: The Intersection of Arts and Politics’ – PUBLIC JOURNAL. Accessed 27 January 2023.

Tihanyi, T et al. (2021) ‘Chelsea Shu on Gunta Stozl’, Make Work Use Art. Seattle: H0W211 University of Washington 2021. Accessed 27 January 2023.

‘The History of Minimalist Furniture Design’— Pamono Stories. Accessed 25 January 2023.

1.1 Carpenter, W. ‘Marcel Breuer & Bruno Weil for Thonet, 1930s’, Pamano Stories

1.2 La Prairie. ‘The Legacy of the Bauhaus Design Movement’

2.1 Skender, M. ‘History of textile art: Gunta Stölzl (1897-1983)’, Textile Artist

2.2 Barbican Centre. ‘Bauhaus Art as Life- Gunta Stolzl: A Daughter’s Perspective.’

3.1 Fischer, J. ‘Gunta Stolzl’, Hausaufderalb

4.1 Gunta Stolzl. ‘With Yael in Zurich’.

4.2 Grand Tour of Modernism. ‘Bauhaus Dessau’

5.1 Cogley, B. ‘Textiles by artists Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl revived for Bauhaus’ 100th anniversary’, Dezeen

5.2 Bello, A. ‘Chair 1921’, Art Station

5.3 Gunta Stolzl. ‘The Development of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop’.

Bauhaus Art as Life-Gunta Stolzl: A Daughter’s Perspective. Barbican Centre. 21 June 2012. Accessed 25 January 2023.

Bergdoll, B. et al. Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity. Edited by A. Sudhalter. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States of America, 2009.

Kane, J. (2002) A Type Primer. Laurence King.

For the Bauhaus 1919 to 2023. Radical innovations in design education exhibition at the Bauhaus Archive Knesebeckstr. 1-2

Berlin, Germany

Phone: +49 30 2540020

Email: bauhaus@bauhaus.de https://www.bauhaus.de/en/kontakt/

Copyright © 2023

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author, except as permitted by Irish copyright law. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that neither the author nor the publisher is engaged in rendering legal, investment, accounting or other professional services. While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional when appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, personal, or other damages.

Book Cover by Rachel Byrne