Toilet, the flushed

Shengzhe

Royal

"The dream has become a nightmare.”

“It feels like we’re in a prison. life is too difficult.”

exposed bare.

the infection.

List of Illustrations

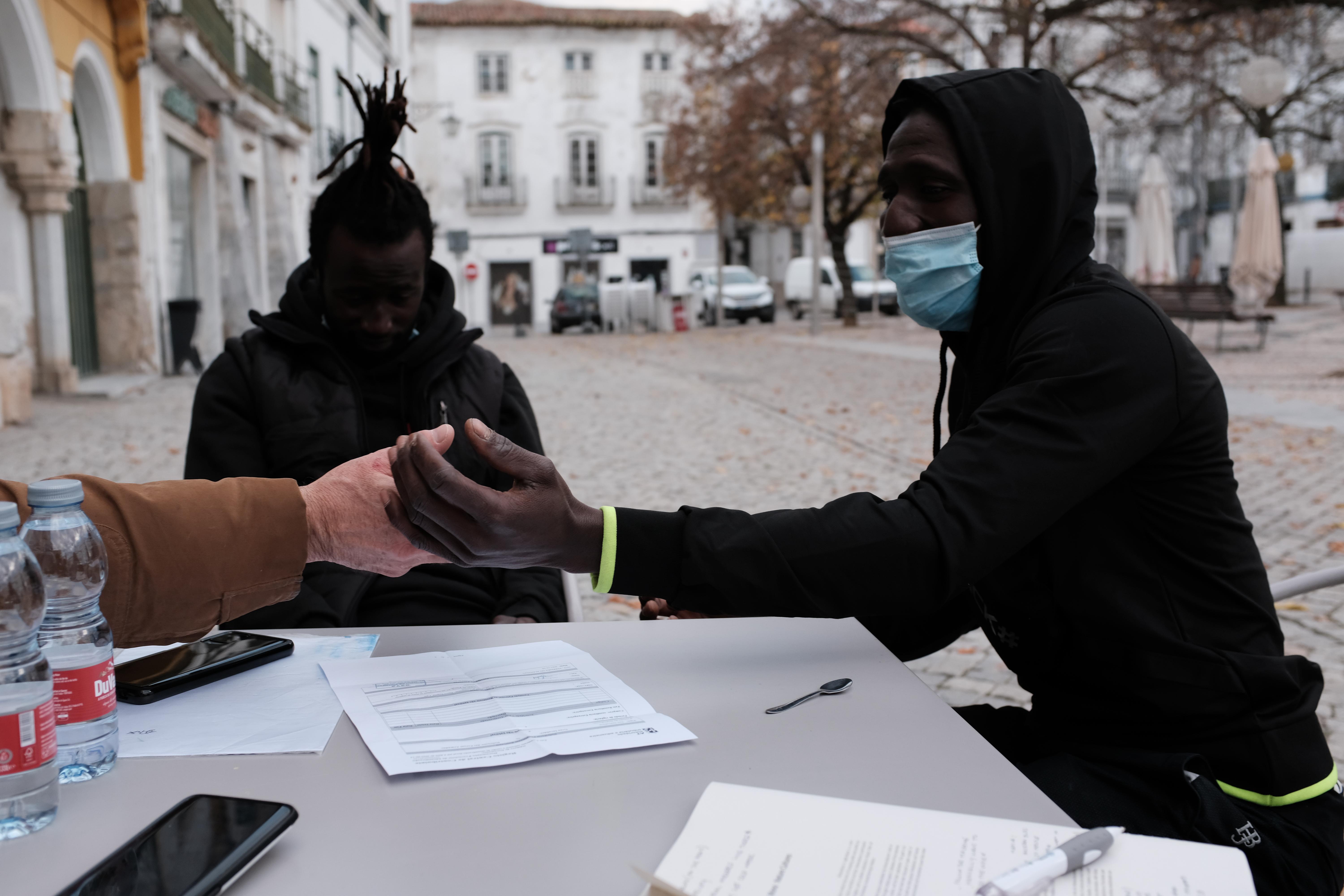

Figure 1 (Page 6)

Beja: the Portuguese city that is the square of modern slavery / Beja: a cidade portuguesa que é praça da escravatura moderna.

https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2022/02/16/beja-a-cidade-portuguesa-que-e-praca-da-escravaturamoderna

Figure 2 (Page 8)

European Journal of Wood and Wood Products.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Containers-in-Alentejo-Source-Guedes-2018_fig4_344751190

Figure 3 (Page 14)

My own work during the field trip of the RS3 research unit of the environmental architecture program at royal college of art.

Figure4 (Page 16)

My own work during the field trip of the RS3 research unit of the environmental architecture program at royal college of art.

Figure 5 (Page 18)

My own work during the field trip of the RS3 research unit of the environmental architecture program at royal college of art.

Figure 6 (Page 19)

My own work during the field trip of the RS3 research unit of the environmental architecture program at royal college of art.

The Toilet, an extension of our body, the benchmark of human civilisation; We use it several times a day, we measure the modernisation by the cleanliness of the toilet; We link our desire for the toilet to freedom. But the issue of public toilets has evolved from being an embarrassing subject to one that is gaining widespread awareness and generating lively discussions In recent years. Although the toilet is generally considered a common space, the toilet is "the greatest necessity" for those who lack an adequate or accessible toilet supply is a critical practical problem.

This essay starts with the primarily existing labour exploitation & human trafficking in Portugal among migrant workers, mainly from Asia and Africa . They work primarily in a novel form of the1 intensive agriculture sector. Such instability, exploitation and abuse of agricultural workers have taken many forms. Workers often work in dangerous and unsanitary conditions; the lack of adequate or accessible toilet supply in working spaces and at home is an essential practical problem in their daily lives. The issues surrounding toilet access were a huge challenge for the migrant workers but were often neglected by media reports. The way individuals can manage bodily functions such as urination, defecation and menstruation are at the core of human dignity. Toilet, for them, has become an indicator of their injustice, inhumane treatment and exploration.

Key Words

Extraction; Labour exploitation; Body politics; Toilet; Cultural identity;

Portugal: Asian migrant workers in agriculture at heightened risk of labour exploitation & human trafficking. https://www.business-humanrights.org/1 en/latest-news/portugal-asian-migrant-workers-in-agriculture-at-heightened-risk-of-labour-exploitation-human-trafficking/

"The dream has become a nightmare.”

Thinking about the toilet and its function as a material and socio-cultural environment, and provides an opportunity to think about the form of identity from many aspects. In this case, the migrant workers in Portugal use the toilet as a way of representing their injustice. In recent years, the demand for low-price workers has significantly risen “thanks” to Portugal’s agricultural success. Subsequently, the exploitation of migrant workers is exceptionally rampant in rural Portugal. The workers are often brought by gangs of traffickers. They are forced to endure inhumane living conditions, constantly working more than 10 hours a day and brutally exploited by dubious temporary employment agencies that place them on farms. The term “slavery” is often used to describe when it comes to their situations. Migrant workers are exploited in all countries that form the EU. the investigation started from the intensive agriculture area in the Alentejo region, South2 Portugal. High temperatures, tiring shift work, poor accommodation and hygiene conditions, and low wages make farm work has become one of the most exploitative jobs in Portugal society.

According to the World Health Organization, 2 billion people still do not have basic sanitation facilities, including toilets. Diseases spread rampantly when proper sanitation is not in place. This3 phenomenon consists of various and interrelated issues, including economy, policy, supply, planning and design, cultural attitudes, habit, behaviours, public health, social demeanour, safety, cleaning methods, maintenance, accessibility for persons with disabilities, the development of norms and standards, policies and legislation, management, research and development, technology, public education and environmental issues, such as water and sewage treatment and recycling. But these issues differ again in varying urban, suburban and rural locations. The degree of development or affluence in each area also plays a vital role in determining needs and priorities. The specific aspects that will be unfolding and exploring in this essay are identity, dignity, embodiment and human right through this narrow-lized public toilet space access among Portugal migrant workers. In the book right to research, the author stated that knowledge like labour market shifts, migration4 paths, prisons, and law are now critical to the exercise of citizenship or the pursuit of it for those who are not full citizens. But the reality is that the lower 50% are not even in the knowledge game because they are starving, dispossessed or economically marginal. Most of the time, migrant5 workers have to move around the entire agricultural area to fit the harvest dates and seasonal changes. This instability allows almost no one to settle down. Such exploitation and abuse may take

Step up rights protection of exploited migrant workers. https://fra.europa.eu/en/news/2021/step-rights-protection-exploited-migrant-worker

Health Organization, Sanitation. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sanitation

The right to research. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14767720600750696

The right to research. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14767720600750696

severe forms: undocumented workers often work in dangerous and/or unsanitary conditions; Many people did not receive wages or received less than agreed wages and were dismissed without proper notice. One of the most significant issues is related to housing: about 90% of people sleep in poor conditions. According to the direct contact with workers, some employers rent garages; they have6 nothing: no bathroom, no water, no lights. Other people allocate in portable container houses, which are removed after the work is completed. Most local landlords don't want to rent their houses to immigrants. Based on the data from POLITICO EU , the covid infection rate among migrant7 workers who are allocated in such conditions is almost 30 times the national average.

The diversity of the debate surrounding toilets shows significant differences in sanitation worldwide. For example, the most urgent case is in global north countries people often have8 difficulties accessing toilets due to various reasons including safety concerns, hygiene or merely lack of an available toilet. Unfortunately, migrant workers who come to global south countries for a better life, including but not limited to Portugal and even in refugee camps, are still facing the exact same issue. In some extreme cases in the refugee camp, some must be afraid of being harassed or even raped when going to the toilet. It undoubtedly highlights severe problem barriers. Environmental barriers include natural barriers or infrastructure-related barriers. For them, there is too little water and no sanitary facilities. The facilities could be located in remote areas, which

sometimes results in open defecation when they are in their workspace.

Ironically, this form of exploitation usually incurs enormous debts. Many have entered Portugal through informal or asylum applications and lack an understanding of Portugal's immigration system. They seek jobs by word of mouth from their peers, and therefore, having to work long hours in harsh conditions and receive only wages lower than the minimum wage has become a routine. The economic and social conditions of migrant workers' home countries and Portugal are necessary backgrounds for workers to make such complex decisions about their lives. They weighed the bleak prospects at home against the opportunity to improve the living conditions of their families in Portugal; at the same time, their demands meet the expanding intensive agriculture employers for cheap, low-cost labour. Also, family is one of the most significant sources of bearing such injustice to make money. Exploitation against migrant workers is common here, and behind the reason why all these immigrants receive very low wages is the employers flout immigration laws and employment regulations and thus obtain cheap and flexible workers. Most immigrants work in an informal capacity, which makes them quite uneasy. They have little understanding of the immigration system. This problem is exacerbated by the wrong information and their lack of English ability. The workers are not prepared for this underground life. They thought their work was recognised. They hope they don't have to dodge and pay their taxes. Nevertheless, the vulnerability of workers to exploitation and their control over their lives and working conditions fluctuate over time. But it is relatively abstract to merely talk about the exploitation without combining it with workers’ day to day life. Toilet, therefore has become a vivid embodiment of every stage they have to suffer.

Documentation as intervention.

And also, under the classic western image of ‘white, functional and utilitarian’, the toilet was a symbol of modernist values of hygiene and cleanliness, but how the migrant workers from the global south failed to fit in this puzzle and embrace this classic image when they come to a developed country like Portugal. The research starts with using the toilet as a beyond-human testimony as evidence of their injustice experience. The research technics use documentation to gather information, enter official archives, do certain forms of systematic analysis , and disseminate9 their results to various audiences. The interview was assisted by a local NGO principal from the Alentejo region, who helps in all kinds of

navigating Portuguese bureaucracy to

bringing food when subcontractors have run off with work as money. Before the pandemic, migrants lined up in front of his office, and now almost everything has to be done by phone. He says that only Portuguese citizenship can give these people security and freedom from the control of the mafia who is long arm reaches the migrant's homelands. Due to privacy and safety concerns, the facts, condition and migrant workers’ personal experiences that will be illustrated in this article are primarily through oral stories anonymously, which was collected and had a direct dialogue with, during a field trip in Portugal.

Dialogue

In December 2021, This study examined migrant workers from Africa who work for Alentejo's intensive farming sector. The interview was conducted in Beja central square; Beja is a town in Alentejo. Face as many of the same problems as other small towns in Portugal. There are more elderly than young people, and there are a few activities, and many people are leaving, but these novel monoculture agriculture modes have allowed Beja to prosper. This region’s population is thrived growing particularly from the global south. The study also explored their experiences and exploitation. The following dialogue is directly interviewed with migrant workers in Beja, Alentejo, South Portugal.

NGO principal: this is a big European hypocrisy, they received people enter illegally from Ceuta, so that they can exploit them. the Portuguese farming sector has driven by low cost labor cheap workers play key role. The large farms sign contracts with those to do for the lowest price and that’s only possible by exploiting the highest number of immigrants possible. no one wants to be a slave in their own country. it’s people from abroad who come because there are few Portuguese people who are except such extreme exploitation.

NGO principal: What is your living condition?

Migrant worker A(from Sénégal, speak Spanish): Not water, no electricity. Life is really hard. this is not the condition I expected. We are five guys one room, three guys one room. The boss he also organizes the transport for us but we take a significant cost for his services, The job paying is €600 a month, the minimum wage. 300 go to my family 100 room on the 150 for the tax and stuff and I don’t have money only little subcontractor are taking a significant cut from the workers salaries 1/3 of their wages. I work for 10 hours-15 hours and was don’t don’t think about the rain or sunlight or water food nothing they have treated by like a Buffalo.

NGO principal: Who is your boss?

Migrant worker B(from Gambia speak English): (Name the boss name) There are two guys together you know.

NGO principal: Mafia.

NGO principal: The house you live is here in the town?

Migrant worker B: Yeah its here in the town.

NGO principal: Near the police office? we can talk and visit you if necessary how many people are there in the house?

Migrant worker B: I don’t know exactly but near 20 people.

NGO principal: Who is exploiting that house is he your boss?

Migrant worker B: Yes. The house is not clean, and everywhere is water and we are all working so we don’t have time to clean the house. there are Indian, Pakistani, I can speak to nobody. Today is my 8th days here, I came from Italy, stayed there for 3 year, I cross the border from Libya, Gambia, Sénégal, Mali, Burkina Faso, its a crazy journey you know.

NGO principal: How long did I take you here?

Migrant worker B: 1 year to arrive Europe.

NGO principal: Why did you come to Portugal?

Migrant worker B: I was doing agriculture in Italy for 2 years.before I came here one of my friends told me he came here 2019, he started working without any problem, he told me here in Portugal.

NGO principal: Do you have friend from Gambia?

Migrant worker B: I only know 1 guy, but I don’t know where he lives.

NGO principal: About your boss, did he give you a contract?

Migrant worker B: No he didn't give me a contract.

NGO principal: He promise you the contract?

Migrant worker B: Yes

NGO principal: If he doesn't do it we will press him, its necessary to start your life here

Migrant worker B: exactly.

NGO principal: Based on Portugal law no matter you enter legally or not, if you working with the contract for 12 month, you will legalise without problem.

NGO principal: Say hi to a Gambian migrant worker on the street. The oldest Gambian guy in Beja and the newest. He wanted to meet you. He just starting we need to help him Migrant worker from the street: I see. He is our father here he is a good man. He helped thousands of African.

NGO principal: We still have some problems because we are mostly related to subcontractors and sometimes they don’t keep the right practices with them and so we in those cases we need to talk to the workers and see if they are subjects of any kind of vulnerability

Based on local NGO principal, the migrants are received in Portugal by middlemen who are connected to the mafia in their home countries. They collect the money from the migrants until they paid off the last sentence of €16,000 that a tourist visa cost them. until that moment, they are not free; they cannot change employers. If they do, the guarantee for the repayment of their debt is at risk. They’re ‘enslaved’ here. If someone doesn’t cooperate, the mafia cancels his citizenship application. It’s a digital application. The migrant gets access to it via email with a password. The mafia forces the workers to show them both the email and the password information. They can cancel the process at any time. the mafia makes them pay for everything. not just the tourist Visa but also for the work contract, the tax number, and the registration. many don’t know they’re entitled to health insurance and don’t know that they can get sick pay.

What is the reason behind the reason why they are being forced to accept such exploitation? For some other countries in the EU, the immigration law are very strict. They need a visa to stay there, but here in Portugal, they can stay without a visa and have a chance for applying for the permeant residence, and that’s why so many workers are coming, and many of already tried to start a new life in other EU countries, but workers have to wait six or seven years to get the documents they need if they want to stay in Portugal after getting a passport even though they are no more than €800 per month they say the calm secure life in the south-west of the EU is worth more than money . Most10 immigrants are not so lucky. Officials say their salary monthly is a minimum wage of about 635 euros guaranteed by the state. Still, they must pay their employers for accommodation,11 transportation to the workplace and even food. This usually leaves them with only 10 euros or less per working day. The migrant workers need to save this portion and send money back to their families.

If the worst accident occurs to them, for instance, an industrial accident. it is complex due to the lack of formal employment certificate, and it is often impossible to obtain any medical insurance

How Portugal Quietly Became a Migration Hub. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/05/21/portugal-europe-migration-undocumented-work-residency-10 citizenship-south-asia/

Portugal Increases Minimum Wage for 2020. https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/minimum-wages-news/portugal-increases-minimum-11 wage-for-2020-january-3-2020

refund; that is the reason why many of their compatriots have paid more than 10000 euros for a tourist visa to Europe to the trafficking Mafia to accomplish their dream of a better life in Portugal. If an undocumented worker is arrested for illegal work, they will be deported in most cases and will not be able to receive wages . Even if they succeed in becoming legal residents, they will not be12 able to get rid of this vicious circle, thanks to the huge loans they get to pay traffickers as a way of chasing better life in Portugal.

In the book the three ecologies by Félix Guattari , modern abyssal thinking is about making13 distinctions and in radicalising them. It separates humanity from sub-humanity and converts them into two completely different standards and realities. It’s especially true in this case, even for the toilet they are using on a daily basis. The government regulated dormitories have only occurred a few years ago when migrant rights organisations began to pay attention to the housing conditions14 of workers. The government's response is to build large dormitories only in remote nomad areas.

This behaviour has enabled the government to claim that it had addressed criticism of workers' poor housing conditions. Simultaneously, it ensures that these workers are further divided from the rest of the Portuguese population in space and society. These policies targeting migrant workers have actually deepened the mistrust and gap between local residents and migrant workers.

EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy. https://eumigrationlawblog.eu/

Guattari, Félix. The three ecologies. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005.

Portugal - Migrants & Refugees Section. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/portugal/

“It feels like we’re in a prison. life is too difficult.”

The toilet is a foundational starting point where each of us deals directly with our bodies and confronts whatever it provides, often on a schedule not of our own. It is undoubtedly the same for workers in Portugal. But under such inhumane and imbalanced resource distribution, including but not limited to toilets, accessing it comes up with more concerns.

Is it clean and hygiene that matters merely to me or anyone? Do I have access right to a certain one? or by money, identity? Will there be a proper “Western toilet” on which we can sit, or will we have to squat? If I am from a squatting part of the world, must I risk physical contact with a public appliance? Are we allowed to put the paper cover on the toilet seat? Will there be paper covers I can put on the toilet seat? Do I have to risk physical contact with public equipment if I come from a non-sitting place in the world? 15

For an Indian or Muslim, running water through wash pipes or wiping with a flushing tube is extremely necessary. Think about it; that is why almost all the migrant workers shared that their expectations were inconsistent with the reality of new life abroad in Portugal. Many people find that the preparations they made before travelling - the information they participated in and the predeparture plan - are not fully prepared for them.

Life beyond work.

Fundamentally speaking, the toilet created a huge abyssal line between local Portuguese and16 migrant workers. This means such serious exploitation has changed the way they are living compared to ordinary individuals.

This phenomenon has elicited a core question to each and everyone of us: What about their life beyond in the working field and house? In the city of Beja, where the migrant workers live, based on a search result from Google Maps (the application migrant worker use daily), there are only two public toilets available to use for the entire city. And the allocation of migrant workers indeed radicalised the imbalanced toilet distribution among the general crowd. This unpacks the structural issue relating to toilets in Portugal. Sadly, toilets are a site of inequality not only for unhoused people. Even within the wealthy parts of the world, toilet suffering occurs. People in poor neighbourhoods have fewer places to go, in part due to the lower density of restaurants, bars, shops,

The question comes from Greed, Clara. Inclusive urban design: Public toilets. Routledge,

abyssal thinking. https://www.eurozine.com/beyond-abyssal-thinking/

and public restrooms. Besides picking and choosing to whom courtesy will be extended, commercial establishments are not always open, and indeed those in poor neighbourhoods commonly have irregular hours. Low-income urban areas tend to have high rates of overcrowded housing, defined by more than one resident per room, which makes toilet access a scarcer resource than it might be in homes with more toilets . 17

Furthermore, given the large existed migrant worker landlords who were always reluctant to do the necessary maintenance and repairs to reduce costs or kick out the unwanted tenants, a functional toilet is less likely to be found in the poor and precarious houses. In addition, many policymakers are unfamiliar and indifferent to these issues and inclusive solutions. They often do not have enough inclusive training opportunities. The excluded groups were rarely consulted about their own lives. Here in Portugal, at least in the town where most of the workers are allocated, the situation may have fluctuated for anyone who is considered not to belong to the place.

Also, it is universally recognised that in most parts of the world, men and women use toilets differently; one indirect consequence of this difference in toilet behaviour is that men's and women's public toilets typically remain separate at a time when few other public spaces are segregated by gender. A further consequence is tension between men and women over the toilet.

The research fieldwork didn’t get the chance to connect to the female worker directly, but there is indirect evidence of the injustice and exploitation of female workers. Female migrant workers tolerated other "lighter" forms of violence. In cases like Portugal, female workers know that their success and survival depend on the kindness of their employers, this involved the control of the

Bathroom.

mafia, as previously mentioned. When employers have all the power, women have minimal choices: appease the employer as much as possible, and if the appeasement fails, find a way to go home or escape and lose their legal status. For irregular immigrants, they know that they may be arrested and deported at any time, which makes them more afraid of complaints. This has happened countless times and there have been many instances. Based on the local NGO principal, a migrant woman who had a Portuguese boyfriend here was shipped back to Thailand so that she wouldn’t tell him she had to pay €6000 for the privilege of coming here and being exploited to try to protect her social worker had placed her. in a women’s shelter, the hardest worker said to him and she made this gesture(a knife on the neck) because she was terrified for her family at home.

The irregular status of many female and male migrant workers also prevents them from contacting the Embassy - many people think the embassy will reject them because they do not emigrate through appropriate channels. In addition to the vulnerability brought by immigration status, for female immigrants, especially those engaged in remote work just like the intensive olive agriculture picking, employers can impose additional restrictions on them, coupled with their isolation, leaving them in an invisible situation.

But their injustice when accessing toilets in the city unfolds a larger issue world-widely. That is, no matter in rich places or poor, and more than anywhere else in public life, toilets inscribe and reinforce gender differences. The markings are for "Men" or "Women. There is not just a difference but also a hierarchy, given that women must wait in their separate lines, whereas men usually do not have to wait at all. This "great binary," much less the inequality with which it is often associated, is neither natural nor inevitable. The contributors to this book raise alternative possibilities, both as cultural reformulations and architectural alternatives. The toilet allows us to ask what it might mean to provide equality precisely. This issue becomes complex if it is granted that groups include individuals who are different in fundamental ways.

In the book Land & Animal & Nonanimal by Anna Sophie Springer, she argued that we do not simply sculpt the world to our liking and stop there. Our environment, in turn, is constantly sculpting us; the changes we make to organisms have consequences for how humans conduct themselves. That is particularly true for the blooming monoculture sector in Portugal. The author used the human domestication of dogs as an example and asked: to what extent have humans been domesticated by dogs? in this case would be the toilet. The toilet seems irrelevant compared to agriculture, but all kinds of post-natural formations, existence and landscape of the earth.

Also, James Graham, in the book Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, asked to think about climate change through molecular composition, including atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, methane, etc. We increasingly understand ourselves, our identities, and our political realities through the frame of the molecule. These provide a novel approach to critical engagement in terms of human technology and productivity advancement through the representation of indirect exploitation, even an object, as a way to expose the injustice. More specifically, the development of agriculture, how we are influenced and defined by science and technology and new things that end up ruining our way of going to the toilet. I reckon the similarities between the two paragraphs can help me better understand the role of human beings in natural formation, the climate in the technological explosion era, and how the thing we create are reshaping ourselves.

There is no shared experience because of the diverse cultural background that workers come from. That may apply to all communities and political interests. The key is to tell humans from nonhumans, the toilet does. We could solve the problem, at least in this case, of unequal access, by ending separation.