Volume 1

Political Digest

May 2024

Copyright © 2024 Political Digest

All rights reserved.

Volume 1

Political Digest

May 2024

Copyright © 2024 Political Digest

All rights reserved.

Queen’s University is situated on traditional Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee territory. We are grateful to be able to live, learn, and play on these lands. We recognize the longer history of this territory, which predates the establishment of the European colonies. We also acknowledge the territory’s significance for Indigenous peoples, whose practices and spiritualities continue to develop in relationship to it and its other inhabitants today. Political Digest is committed to countering discrimination and developing a climate of educational equity that respects the equal dignity and worth of all who participate in the life, work, and mission of the University.

Editors in Chief

Cordelia Jamieson

Alexandria Moustakis

Editorial Editors

Layla Artzy

Sidney Burzynski

Editorial Board

Ainsley Croft

Max Gangbar

Tina Hashemi

Julian King

Atticus Lynch

Nicole Ragogna

Esha Sharma

Kennedy Truin

Finance Director

Jackson Cardillo Marketing Director

Leyou Andualem

EDII Director

Xian Tronsgard

Lower Year Interns

Erin Byrne

Arden Bowler

Heli Patel

Rissa Wang

Dear Readers,

This May 2024 volume is a culmination of student work over the past year representing some of the best and brightest of Queen’s Political Studies community. The works in this journal are thoughtful, well written, and critical of the world we’re surrounded by. Our phenomenal authors have written on a variety of topics across political sub-disciplines, including U.S. and Canadian Foreign Policy, Colonialism, Distributive Justice, Feminist International Relations, and more.

This very first volume represents the tireless effort of every individual within the journal. We must first give thanks to our editorial team, whose evaluations of our undergraduate submissions have shaped the work you read within these pages. Political Digest and the work it platforms would not be what it is without the dedicated work of these individuals.

We cannot give enough thanks to our professor reviewers: Emma Fingler, David Haglund, Rachel Laforest, Andrew Lister, Margaret Little, Claire Mountford, and Jana Walkowski. These professors transform student work into publications, and their expertise provides us with the insight and credibility needed to make this publication what it is.

Happy reading! We sincerely hope you enjoy sifting through this as much as we enjoyed putting it together.

Cordelia Jamieson & Alexandria Moustakis Political Digest Editors in Chief, 2023-2024Land Acknowledgment

Political Digest 2023-2024 Team

Letter from the Editors

Limits of Middle-Power Diplomacy: A Poststructuralist Account of the Influence of U.S. Securitization of the ‘China Threat’ on Sino-Canadian Relations

Kelly Buell

Involuntary Pregnancy Ought to be Considered Forced Labour: A Critical Analysis of Dobbs v. Jackson and U.S. Labour Laws

Lauren Kidd

Limited Seats in the Lifeboat: Distributive Justice and Associational Duties as Triaging Principles in Forced Migrant Admissions

Margaret Cavanagh-Wall

Responses to the Masculine State: Examining Black Feminist Transnational Organizing Throughout the Centuries

In May 2015, China’s State Council revealed its newest national initiative ‘Made in China 2025,’ containing a plan to transform manufacturing sectors through the development of 10 high-tech industries. Funnelling government-subsidized investment into high-tech industries such as energy-powered vehicles, next-generation technology (IT) and telecommunications, advanced robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI), the goal of this state-led plan is to reduce Chinese dependency on foreign technology and move towards the establishment of China as the dominant high-tech manufacturer in the global marketplace (McBride and Chatzky 2019). Aligning with contemporary Chinese economic policies, this announcement reignited the debate concerning whether China poses an increased security risk to states, particularly those considered to represent potential impediments to China’s rise as a great power. The subject of this debate is not new but rather contributes to the discourse which has come to be known as the ‘China threat.’ Traced back over a century, the China threat discourse has evolved from initially focusing on threats associated with China’s cultural and social factors to encompassing threats that extend into the political realm (Song 2015). Over the past two decades, the U.S. has been at the forefront of utilizing the China threat rhetoric, publicly criticizing their foreign policy, human rights, and adherence to international trade rules. The U.S. has strategically framed its rhetoric on China, particularly emphasizing security challenges arising from advancements in technologies and the unforeseen vulnerabilities they introduce (Gendron 2013). Notably, predating the ‘Made in China 2025,’ the U.S. employed securitization methods in disseminating the China threat discourse. As a theory, securitization concerns the social construction of a threat and the responses to that threat, emphasizing the political processes that make something a security issue (Friis and Lysne 2021).

The use of securitization and the China threat rhetoric by the U.S. has received increasing academic attention in the last decade. These scholarly debates have tended to focus on whether China poses a real threat to U.S. national security, followed by policy recommendations to stabilize the future of Sino-American relations. While informative for understanding American security interests, there remains a critical gap in understanding the extent to which Sino-American relations influence and impact other state foreign policy with China. Seeking to close this gap in the literature, this paper contributes to existing academic debates in the cybersecurity space by analyzing the breadth of U.S. influence on Canada’s foreign policy decisions with China. Canada’s middle position in world politics makes it a compelling object of study, stuck between navigating diplomatic ties with two major economic powerhouses. Using poststructuralist securitization theory, this paper will argue that the U.S.’ persistent securitization of China, alongside a “with-us-or-against-us” attitude, has significantly shaped Canada’s shift from diplomatic engagement to confrontational strategies, exemplified by the ban on Huawei 5G infrastructure in May 2022, thereby highlighting the profound influence of the U.S. and underscoring Canada’s challenges as a middle-power in navigating relations with China.

The remainder of this paper will be divided into four sections. As the core theoretical approach, the first section introduces securitization theory and how its use as a political strategy supports the expansion of the China threat discourse. The following section analyzes the pattern of U.S. securitization of China using three case studies, namely Titan Rain, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and Huawei, to better understand U.S. success towards shifting public and private perceptions of China as a threat to national security. The third section closely decade-long evolution of Sino-Canadian relations, fo-

cusing on the transition from engagement to confrontation, and delves into the substantial influence of the U.S., exemplified by the arrest of Meng Wanzhou and Canada’s ban on Huawei 5G infrastructure. Lastly, this paper explores the future of Sino-Canadian relations through an analysis of Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, mirroring that of the U.S. and reflecting rising tensions.

The emergence of securitization theory has been attributed to the Copenhagen School and, more specifically, the work of Barry Buzan, Ole Waever, and Jaap de Wilde in the 1990s. This approach was created for the purpose of understanding the process by which something comes to be understood as a threat, moving from the domain of politics into that of security (Buzan and Waever 2009). For this process to take place, securitization involves four components: a securitizing actor, securitizing moves, an audience, and a referent object. According to the authors, this process is initiated through a speech act and occurs when “a securitizing actor uses a rhetoric of existential threat and thereby takes an issue out of what under those conditions is normal politics” (Campion 2020, 49). It is important to note securitization itself does not constitute success, but rather remains dependent on whether the implementation of emergency measures is accepted by the audience.

Securitization theory is considered multidimensional pertaining to various levels of analysis, degrees of comprehensiveness, and the extent of success in convincing the respective audience (Friis and Lysne 2021). Moreover, while the referent object is traditionally recognized to be the state, the multidimensional nature of securitization recognizes that anything may be constructed as a referent object. The emergence of the China threat discourse and use of rhetoric can thus be understood as a product of securitization. With an initial focus on cultural and social threats in the China threat discourse, scholars such as Oliver Turner highlight ideational factors in constructing foreign Chinese identity as a threat to the security of Western identity (Turner 2013). While the U.S. remains the securitizing actor, contemporary securitization methods often

highlight the material and technological dimension of threats––framing Huawei as a threat to a new referent object, American national security. Regardless of the referent object, the fear associated with Chinese identity and cyber espionage activity has created a dominant Western perception of China. Transcending U.S. borders, the portrayal of China as a threat constitutes a successful case of macrosecuritization by the U.S.. In this context, macrosecuritization refers to security narratives that extend beyond the conventional units at the middle level, such as states or nations, elevating the impact of securitization to a broader order. Rather than indicating whether China poses a real threat to U.S. national security, these dominant Western perceptions of China as an ‘other’ demonstrate more about Western self-imagination and the desire for certainty in foreign relations (Song 2015).

The social construction of Chinese ‘otherness’ constitutes a poststructuralist account which is crucial to foster an understanding of American influence on other states. Rather than treating identity as objectively given, poststructuralist accounts seek to reveal underlying forces which influence the formation and acceptance of such identities (Song 2015). When analyzing the emergence of the China threat through poststructuralism, Weiqing Song provides an excellent account, identifying three modes of discursive securitization by actors: scientific theory, normative analogy, and political myth. Song (2015) articulates that securitization using scientific reasoning is applied “as an explanation of the behaviour of great powers that seek to gain as much power as possible over their rivals” (154). When described as a trend rooted in scientific theory, the audience is likely to accept the securitizing claim. Normative modes of securitization may draw on historical analogies and the politics of identity to emphasize the duality of human experiences, depicting China as unusual and dangerous, and the West as normal and proper. It is common for normative securitizing actors to address a large, attentive, and well-educated audience, who “find concrete examples and precedents from history to be rhetorically persuasive” (Song 2015, 158). An example of such is the New York Times, operating as a legitimate international forum for the dissemination of knowledge pertaining to current world issues. By strategically framing issues through identity politics, the New York Times

presents China as unconventional while portraying the West as the standard. Lastly, Song demonstrates how securitizing actors have used political myths in framing China as a threat, addressing the general public to maximize reach. When articulating a political myth, it matters not that the information articulated is factual, but rather that the audience is successfully persuaded, and ultimately convinced, that something is a security threat which requires urgent action by the state (Song 2015).

In general, a securitization act is only successful if it achieves the intended effect. While the intended effects of securitizing actors have shifted over time, the near-consistent dissemination of the China threat has produced an overwhelmingly dominant perception of China as dangerous to the West, providing acceptance and justification for policy implications by securitizing actors. Therefore, when choosing between a particular mode of discursive securitization to construct something as a threat, securitizing actors should be recognized as making a political, rather than analytical, decision (Eriksson 1999). The purpose of the following section is to better understand such political objectives by analyzing different cases of U.S. securitization of China over the last two decades.

As a former hegemon, the U.S. has successfully disseminated knowledge regarding the superiority of Western ideology, culture, economics, and political democratic systems around the world. Accelerated by the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, the rapid development of the West was often compared to the overall stagnation of foreign regions such as China (Campion 2020). However, shifting Chinese economic policies in the 90s resulted in the expansion of the China threat discourse. Rather than displays of confidence in strengthening U.S. security, the states’ inflated use of the China threat rhetoric signalled increasing fear and hostility regarding China’s rise. Over the past two decades, China’s rise and subsequent responses by the U.S. have created a dominant Western perception of China which remains rooted in such fear. Considering this historical pattern and increasing hostility in contemporary Sino-American diplomacy,

the U.S. is considered to be the predominant securitizing actor in the West. The remainder of this section will analyze three distinct cases whereby the U.S. successfully securitized China which, when analyzed together, demonstrate a pattern of choices rather than a mere occurrence. Moreover, the success of such securitization of China by the U.S., rather than being predicated on any singular event, should be recognized as the cumulative result of the China threat rhetoric.

In 2005, Titan Rain became the first instance of state-sponsored Chinese espionage released to the public. The report indicated China-based hackers were successful in accessing networks of the U.S. Department of State, Homeland Security, and Energy, resulting in the estimated theft of between 10-20 terabytes of U.S. intelligence data between 2003 and 2005 (Scissors and Bucci 2012). For the first time, Titan Rain triggered attempts to reduce the extent by which Chinese cyber operations could adequately target U.S. markets and has thus become recognized as the instance by which Sino-American distrust and suspicion took shape.

Under a poststructuralist account of securitization, Titan Rain aligns with scientific theory as its mode of securitization. The revelation of state-sponsored Chinese cyber espionage supports the narrative which emphasizes the pursuit of power and control. Simultaneously, Titan Rain aligns with Song’s (2015) articulation of normative analogy by framing China’s actions as deviating from accepted norms, reinforcing the duality of experiences between China and the West.

Corporation (CNOOC)

Later that year, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) attempted the acquisition of U.S.-based Oil Company, Unocal, for $18.5 billion (Campion 2020). Despite being a commercially attractive opportunity, feelings of fresh skepticism toward China ultimately influenced the U.S.’ decision to decline CNOOC’s request for acquisition. When providing justification, U.S. elites claimed that

China’s acquisition of Unocal presented a threat to American national security. This was particularly due to CNOOC’s qualification as a state-owned enterprise (SOE), which not only provided an innate link to the Chinese government, but simultaneously created an unfair comparative advantage via accessing non-market capital. Rather than demonstrating an abrupt shift to exceptional security politics, as often articulated by securitization theory, the U.S.’ refusal to sell Unocal due to national security threats remained in the realm of normal politics, simultaneously protecting its own economic and security interests (Campion 2020). Under poststructuralist securitization theory, the CNOOC case exemplifies normative analogy as a mode of securitization by drawing upon historical precedents and identity politics. The rejection of the acquisition bid by the U.S. reflects this normative securitization approach, tapping into historical analogies and identity politics to successfully portray China as threatening due to its status as an SOE.

In the years following 2005, the China threat rhetoric continued to circulate in the U.S., setting a precedent for future responses to Sino-American relations. In 2010, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) released a risk-mitigation statement, warning the public that Chinese companies could pose a threat to the U.S. (Friis and Lysne 2021). Two years later, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee accused Huawei of stealing American intellectual property (IP) and urged the U.S. government to block Huawei from further contracts and acquisitions to reduce risks associated with espionage activity. Despite Huawei officials repeated denial and demand for proof of U.S. accusations, a combination of growing Sino-American economic competition and strengthening public perceptions of China as dangerous made the successful operation of Huawei difficult in the U.S..

Rising Sino-American tensions were exacerbated following the election of President Donald Trump in 2016 and the establishment of the Chinese Intelligence Law in 2017. During his 2016 Campaign and official Presidency, Trump remained consistent in his personal perception of China and his vision for Sino-American relations. Aiming to reduce the $346

billion trade deficit, Trump pursued a confrontational approach with China in areas of trade, industrial production, and the imposition of tariffs (Bratt 2021). While Trump’s China threat rhetoric remained inconspicuous during his first year in power, the 2017 Chinese Intelligence Law prompted a response by the Trump administration which took on a securitizing hue. The establishment of this law, in effect, legally obliges all Chinese companies to turn over information to, and comply with, China’s intelligence and security services (Friis and Lysne 2021). Rather than empty accusations by the U.S. regarding China’s pursuit of clandestine foreign espionage through Huawei, the Chinese Intelligence Law enforced such sharing of information which legitimized constructions of Huawei, and by extension China, as a potential threat to American national security. Less than a year later, the U.S. successfully banned Huawei 5G infrastructure and simultaneously placed Huawei on an entities list, thereby restricting the ability of the telecommunications company to purchase American products. In addition to securitization at the state-level, the U.S. embarked on a global macrosecuritization campaign to oppose foreign implementation of Huawei 5G infrastructure, arguing that its use not only threatens national security but compromises any intelligence sharing between states (Friis and Lysne 2021). Compared to these traditional scopes of securitization, macrosecuritization broadens the dimension between the securitizing actor and the audience, raising the possibility of multiple audiences across many units (Buzan and Waever 2009). Thus, the US’ macrosecuritization of Huawei greatly influenced the foreign policies of each member state to the Five Eyes. As the final member state to restrict or ban Huawei 5G infrastructure, the following section examines Canada’s shifting Chinese foreign policy to better understand the breadth of U.S. influence as the main securitizing actor in the West.

Following poststructuralist securitization theory, the U.S. employs political myth in its securitization and macrosecuritization of Huawei, crafting a narrative that may not be firmly grounded in factual evidence but, instead, seeks to convince the public of the urgency to address the perceived threat. Simultaneously, the dominant portrayal of Huawei as dangerous and straying from accepted norms in Western states reflects the presence of normative analogy as a tool

of securitization under poststructuralist securitization theory.

Contemporary Sino-Canadian relations have been criticized as being at their lowest point in recent years, characterized by securitization scholars as the shift from engagement to confrontation (Lim 2020). As a middle-power in world politics, Canada recognizes its constraint compared to the U.S. in terms of influence, economic, and military power. However, despite the improbability that Canada would influence Chinese behaviour, the shift from quiet diplomatic engagement to confrontation raises significant questions for Canada. By exploring Sino-Canadian relations since the beginning of Trudeau’s tenure in 2015, the remainder of this section will analyze and reveal the nature of U.S. influence on Canadian foreign policy with China.

With the ultimate aim to increase prosperity for Canadians at home, Trudeau attempted to expand Sino-Canadian economic engagement on both diplomatic and commercial fronts. The most substantial example of diplomatic engagement followed a meeting between Premier Li Keqiang and Trudeau in 2018, whereby “both sides pledged to expand trade to launch exploratory discussions for a possible Canada-China Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and to expand links between individual Canadian government departments and their Chinese counterparts” (Lim 2020, 28). Among many others, this meeting fostered the goal of doubling bilateral trade by 2025, based on 2015 statistics. On the commercial front, the Liberal Government’s use of the 1985 Investment Canada Act (ICA), which allowed the Canadian government to conduct national security reviews of foreign investment that could be blocked or authorized and subject to certain conditions, also strengthened Sino-Canadian engagement. One of the most significant national security reviews was Hong Kong’s O-Net Communications proposed acquisition of Montreal-based ITF Technologies in 2017. While initially blocked by Trudeau’s predecessor in 2015 due to national security fears regarding the Chinese firm’s partial ownership by an SOE, Trudeau’s Liberal Government overturned this

decision, approving the acquisition subject to certain conditions (Lim 2020).

While engagement was fostered on economic and diplomatic fronts between China and Canada at the start of Trudeau’s tenure, it did not prove to be entirely sustainable in 2018 when Canada confronted Chinese issues related to human rights, adherence to international trade laws, and espionage activity. Following the United Nations (UN) report in 2018, which condemned China’s role in the detainment of one million Uighurs in internment camps in Xinjiang, Canadian political elites broke traditional quiet diplomacy and demonstrated concern over such human rights. While Trudeau was initially criticized in his response to continue developing an FTA with China, Liberal members have since voted to label these actions a genocide (Cecco 2021).

Later in 2018, Sino-Canadian relations dominated headlines following the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO and daughter of Huawei founder, at the Vancouver Airport. The arrest followed a U.S. extradition request, by which Canada was bound, on the suspicion that Meng violated U.S. sanctions with Iran. Transpiring only a few months after the U.S. banned Huawei 5G infrastructure, the Chinese embassy in Ottawa was quick to blame the arrest on U.S.-Canada political conspiracy (Bratt 2021). Moreover, to re-establish political power, the Chinese government detained two Canadian citizens, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, only two days following the arrest in Vancouver. While independent of concerns related to 5G security or Huawei, the mutual arrests prompted a public response from Trudeau, sparking a series of economic sanctions against Canada as well as raising security tensions and political strains on Sino-Canadian relations.

The strained Sino-Canadian relationship was also tested by the U.S.’ securitization of Huawei as a threat to American national security. In addition to securitization at the state-level, which informed Canadian public opinion as well as that of Americans, the U.S.’ choice to macro-securitize China via a global anti-Huawei campaign presented Canada with a difficult choice. Strengthened by a bipartisan response, American Congressmen across both parties opposed

the inclusion of Huawei in Canada’s 5G infrastructure, “arguing that its involvement would make America vulnerable” (MacDonald and Kapelos 2019).

The U.S.’ “with-us-or-against-us” attitude presented Canada with an ultimatum, forcing the state to choose between salvaging economic relations with China or maintaining national security with its U.S. ally and intelligence services such as the Five Eyes. Despite receiving warnings from China, such as the threatening message from China’s ambassador to Canada, Cong Peiwu, stating Canada would “pay a price for their erroneous deeds and actions” if it were to pursue the ban against Huawei, Canada ultimately decided to align with its closest ally and the remaining Five Eyes countries (Boynton 2022). Canada made the official decision to ban Huawei 5G telecommunications from infrastructure in May 2022. Given the heavy investment in Huawei infrastructure across Canada, this decision will undoubtedly make telecommunications more expensive across the country (Carvin 2021). However, Trudeau has claimed “his government took the time needed to ensure the decision to ban Huawei would keep Canadians and the economy safe” (Zimonjic 2022). Reducing vulnerability to Chinese espionage activity is considered crucial for the overall safety, stability, and future prosperity in the West.

Due to the recent nature of Canada’s choice to ban Huawei 5G infrastructure, it is difficult to foresee the consequences on the future of Sino-Canadian relations. However, Canada’s recent publication of the 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy provides clarification regarding Canada’s intentions for foreign policy decisions and future relations with China. Despite describing China as an increasingly disruptive global power, Canada ultimately refers to China as necessary “to address some of the world’s existential pressures, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, global health and nuclear proliferation” (Brewster 2022). Additionally, Canada proposed revisions to the Investment Canada Act (ICA) which will ensure protection over national security by preventing SOEs and other foreign entities from acquiring Canadian industries and intellectual property. According to a CBC publication, Canadian intentions for foreign policy mirror the U.S.’

most recent vision for engagement, demonstrating the weight of American influence in designing Canadian foreign policy decisions (Brewster 2022). Related to the similar intentions with its U.S. ally, Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy reflects the lasting impacts of international clashes and rising tensions governing Sino-Canadian relations. Most prominently, these include the arrest and extradition of Meng Wanzhou and China’s retaliatory detention of Spavor and Kovrig, as well as Xi Jinping’s recent conversation with Prime Minister Trudeau at the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia in November 2022.

In addition to the detainment of two Canadian citizens, China retaliated against the arrest of Meng Wanzhou by imposing a series of economic sanctions on Canadian exports to China. Often perceived as a punishment for small countries who butt heads with Beijing, China’s imposition of sanctions on Canadian canola oil and meat products resulted in a loss of $4.5 billion in exports in 2019 (Lim 2020; Bratt 2021). Chinese contention with Canada remained evident three years later during a conversation between leaders at the G20 summit in Nov. 2022, where President Xi Jinping was recorded publicly scolding Prime Minister Trudeau over accusations related to leaking private conversations to the media. This leaked material pertained to China’s clandestine funding of 11 candidates during the 2019 Federal Election. Acting outside of ordinary diplomatic relations with other G20 countries, Saint-Jacques told CBC that “Xi’s purpose was to make Trudeau lose face publicly at home and around the world” and noted that this very well could introduce new economic or diplomatic implications between China and Canada in the future (Gollom 2022).

In the context of the escalating tensions with China over the past four years, this paper utilizes poststructuralist securitization theory to argue that the persistent securitization of China by the United States, coupled with a “with-us-or-against-us” attitude, has significantly influenced Canada’s foreign policy trajectory. Explored in the preceding sections, the ban on Huawei 5G infrastructure in May 2022 serves as a clear example of this shift from diplomatic engagement to confrontational strategies, underscoring the profound impact of the U.S. on Canada’s position as a middle-power in world politics. Notably, Canada’s In-

do-Pacific Strategy aligns with this cautious approach dictated by U.S. influence, as reflected in its anticipation of repercussions on Chinese foreign policy and subsequent alignment with its U.S. ally. This strategic alignment emphasizes the complexity of Canada’s role as a middle-power, requiring a balance between asserting influence and recognizing inherent constraints due to its position. The intricacies of Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy highlights the country’s commitment to collaborative diplomacy amid shifting geopolitical landscapes, accentuating the nuanced challenges embedded in navigating the intricate web of world politics.

This paper has provided a deeper understanding of the breadth of U.S. influence on Canada’s shifting foreign policy and relations with China. It positioned the U.S. as a securitizing actor, constructing its Chinese competitor as a threat to national security and revealing the poststructuralist nature of the China threat rhetoric. Moving beyond the traditional focus on whether China poses a genuine threat to U.S. national security, this paper employed a poststructuralist securitization approach to understand the extent of U.S. influence on Canada’s foreign policy trajectory with China.

The first section identified the China threat discourse as a product of securitization. While threats have shifted from containing cultural and social threats to the inclusion of political threats, the aim of the securitizing actor has remained the same: to socially construct China as a threat (Lim 2020). The first section also identified three modes of discursive securitization used in the process of “othering” China, which include the scientific theory, normative analogy, and political myth (Song 2015). Depending on the intention of the securitizing actor, the pursuit of securitization using one or more of these modes constitutes a political, rather than an analytical, decision (Erikkson 1999). After identifying the U.S.’ construction of a dominant Western perception of China, the following section considered U.S. modes of securitization of the China threat. This was accomplished by considering three distinct examples: Titan Rain, CNOOC, and Huawei. The securitization of Huawei as a threat to national security by the U.S. aligned with macrosecu-

ritization, influencing both domestic opinions of China and international foreign policies respectively. The U.S.’ international influence was depicted in the third section, analyzing Canada’s shift from engagement to confrontation with China since 2015. Breaking away from its traditional quiet diplomacy, Canada began condemning China’s human rights abuses, adherence to international trade laws via the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, and acts of potential espionage activity by choosing to ban Huawei. While the shift in Sino-Canadian relations is considered to be at its lowest point in recent years, Trudeau can be positioned as firmly standing up to China in recent efforts to protect Canadian citizens and the future success of the West (Lim 2020).

While it is difficult to fully predict how these recent actions will shape future Sino-Canadian relations, the final section analyzes Canadian intentions through its Indo-Pacific Strategy. Constrained as a middle-power in world politics, Canada recognizes the necessity of fostering strong Sino-Canadian relations in the future due to China’s rising economic power (Brewster 2022). This mirrors the American Indo-Pacific Strategy, demonstrating the strength of U.S. influence on Canada’s foreign policy with China. This paper is not meant to assume that U.S. international influence is the only explanation for shifting Sino-Canadian relations but rather suggests that the combination of U.S. securitization of the China threat alongside its “with-us-or-against-us” attitude constitutes significant reasoning for Canada’s decision to ban Huawei 5G infrastructure, and more generally Canada’s shifting foreign policy trajectory with China since 2015.

Bratt, Duane. “Stuck in the Middle with You: Canada–China Relations in the Era of US–China Clashes.” Political Turmoil in a Tumultuous World: Canada Among Nations 2020 (2021): 273-294.

Boynton, Sean. “China will see Canada’s Huawei, ZTE bans as ‘a slap in the face’, experts Warn”. Global News: Canada. (2022). Doi: https://globalnews.ca/ news/8849155/canada-huawei-zte-ban-5g-china-tensions/

Buzan, Barry, and Ole Wæver. “Macrosecuritisation and security constellations: reconsidering scale in securitisation theory.” Review of international studies 35, no. 2 (2009): 253-276.

Brewster, Murray. “Trudeau government unveils long-awaited plan to confront an ‘increasingly disruptive’ China.” CBC News: Canada. (2022). Doi: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-china-trudeau-xi-taiwan-1.6664854

Campion, Andrew S. “From CNOOC to Huawei: Securitization, the China threat, and critical infrastructure.” Asian Journal of Political Science 28, no. 1 (2020): 47-66.

Carvin, Stephanie. “Stand on Guard: Reassessing Threats to Canada’s National security.” Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (2021).

Cecco, Leyland. “Canada votes to recognize China’s treatment of Uighur population as Genocide.” The Guardian: Toronto. (2021). https://www.theguardian. com/world/2021/feb/22/canada-china-uighur-muslims-genocide

Eriksson, Johan. “Observers or advocates? On the political role of security analysts.” Cooperation and conflict 34, no. 3 (1999): 311-330.

Friis, Karsten, and Olav Lysne. “Huawei, 5G and security: Technological limitations and political responses.” Development and change 52, no. 5 (2021): 1174-1195.

Gendron, Angela. “Cyber threats and multiplier effects: Canada at risk.” Canadian foreign policy journal 19, no. 2 (2013): 178-198.

Gollom, Mark. “Why Xi Jinping publicly rebuked Justin Trudeau, and what it means for Canada’s with China.” CBC News: Canada. (2022). https://www.cbc. ca/news/politics/china-justin-trudeau-xi-1.6653939

Haveman, Michelle, and Jeroen Vochteloo. “Huawei: A case study on a telecom giant on the rise.” Multinational Management: A Casebook on Asia’s Global Market Leaders (2016): 75-94.

Lim, Preston. “Sino-Canadian relations in the age of Justin Trudeau.” In Trade and Conflict, pp. 25-40. Routledge, 2022.

MacDonald, Brennan. and Kapelos, Vassy. “Canada could threaten US security by allowing Huawei into 5G network, says US senator”. CBC: Power and Politics. (2019). https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/powerandpolitics/canada-huawei-5g-tech-riskus-1.4965297

McBride, James, and Andrew Chatzky. “Is ‘Made in China 2025’a threat to global trade?” Council on Foreign Relations 13 (2019).

Scissors, Derek, and Steven Bucci. “China cyber threat: Huawei and American policy toward Chinese companies.” The Heritage Foundation 3761 (2012).

Song, Weiqing. “Securitization of the” China Threat” discourse: A poststructuralist account.” China Review 15, no. 1 (2015): 145-169.

Turner, Oliver. “‘Threatening’ China and US security: the international politics of identity.” Review of International Studies 39, no. 4 (2013): 903-924.

Zimonjic, Peter. “Trudeau says Huawei, ZTE 5G ban took longer because government wanted to get it right.” CBC: Canada, Politics. (2022). Doi: https:// www.cbc.ca/news/politics/trudeau-huawei-ban-cyber-security-1.6461235

Kelly Buell (she/her) is a fifth year Political Studies Major and Global Development Minor.

Her research interests are: International Relations, Security Studies, and International Law

Introduction

Dobbs, state Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization et al. marked the overturning of Roe and Casey, ending the constitutional protection of the right to an abortion across the United States of America. Dobbs v. Jackson decided “the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives” (Dobbs v. Jackson 2022, 1). While anti-choice movements and the Supreme Court argue abortion banning laws are done to protect the fetus’ life and govern justice for the child, this does not change the nature of a forced pregnancy being non-consensual labour. If pregnancy was legally recognized as labour and thus protected by the U.S. Department of Justice, the overturning of Roe v. Wade would have been illegal.

This paper will first examine legal conceptualizations of both reproductive labour and forced labour. Following this, it will discuss why gestational labour is not currently legally protected or recognized as labour but ought to be. Furthermore, it will argue that recognizing pregnancy as labour under U.S. law could enable the invocation of 18 U.S.C. § 1584 to identify non-consensual pregnancy, particularly resulting from non-consensual conception (e.g. rape), as involuntary servitude. This paper will then argue that it should be illegal to deny individuals the right to an abortion by asserting that a pregnancy, which the gestational parent wished to have aborted, should be considered involuntary servitude under 18 U.S.C. § 1584. By arguing pregnancy should be legally recognized as labour and, thus, a forced pregnancy constitutes forced servitude, this paper will assert that individuals should have the legal right to an abortion as the means to end involuntary servitude.

Definitions of labour are commonly divided into two distinct categories of productive labour and reproductive labour. Productive labour “results in goods or services that have monetary value, for which producers receive a wage” (Armstrong 2022, 171).

Reproductive labour refers to unpaid labour done in the private or domestic sphere which includes and is not limited to childbearing, cooking, and cleaning. The term and referral to gestational labour throughout this paper will only refer to the physical labour done in the womb by the gestational parent to create a child. Throughout this paper, the term reproductive labour will be used to reference all other forms of reproductive labour such as cooking or cleaning.

Feminist scholars, such as Margaret Benston, have long recognized that reproductive labour is work and necessary for productive labour to occur (Balka 1991). Although it is not unusual to find literature that discusses recognizing reproductive labour as labour and contributing to the capitalist workforce, such literature regarding gestational labour and the necessity of labour consent is less popular in comparison. Similarly, the overturning of Roe v. Wade does not account for the possibility that the inability to get an abortion will result in forced labour; this is the gap this paper will attempt to address. Throughout the entire Dobbs v. Jackson ruling, neither reproductive labour, gestational labour, nor gestational work are mentioned. The references to a gestational parent’s consent to pregnancy first includes the dismissal of assumed consent if the gestational parent has not terminated the pregnancy before the child could live outside the womb. Secondly, it is assumed a gestational parent has consented to being pregnant “after fifteen weeks, well beyond the point at which nearly all women are aware that they are pregnant” (Dobbs v. Jackson 2022, 138). The only referral to rape is by Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia

Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan in their dissent.

There is no concrete definition of labour in U.S. law. Instead, U.S. Labour law only specifies what labour can be regulated and is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Labour. Such regulation has been shaped by capitalist definitions of productive labour, specifically labour that can be enforced by an outside agent, requiring a level of consent from the labourer. The U.S. Justice System and Department of Labour do not enforce reproductive labour standards and consequentially the overturning of Roe v. Wade does not account for the consequences of labour involved in pregnancy.

Capitalist understandings of labour define the boundaries of the U.S. Department of Labour, which is responsible to protect employee rights, labour relationships, and ensure officials adhere to the highest standards of responsibility and ethical conduct in labour organizations and labour management relations (U.S. Department of Labour). Gestational labour standards are not enforced by the U.S. Department of Labour because pregnant individuals are not an employee with an employer (U.S. Department of Labour). Pregnancy does not systematically or transactionally produce capital for an employer or a removed individual. While the physical acts of some reproductive labour can be valued, it must be considered employment and directly involved in the capitalist system of accumulation, monetary exchange, and goods production to be valued and be under the jurisdiction of state organizations (U.S. Department of Labour).

It is not the essential physical acts of the labour which dictate whether it is recognized as work but rather the level of consent and enforceability involved. It is assumed that labour is capable of being exploited and enforced if it is being controlled by an employer. Without an employer it is assumed to be self-governing consensual actions or volunteer work. This section will argue that it is the level of consent involved by the worker which defines something as recognized

labour that is capable of being exploited, not the actual physical act(s) of labour. This is exemplified though the social recognition of paid reproductive labour.

Any productive process committed by a human can be considered labour regardless of the type of work, if it produces capital, or is done for an employer. Society and law already recognize reproductive labour as value producing labour. For example, it is widely considered valued labour to run a nursery, day care, baby sit, be a personal chef, or a cleaner. These practices are all reproductive labour that a parent will do as unpaid labour when raising a child. The physical acts of labour done by a parent or guardian is not often physically different than that of hired help. Furthermore, the recognition of volunteer work as unpaid labour proves it is not the necessity of monetary exchange for something to be recognized as labour but consent to work for another. One can perform reproductive labour for another individual without being paid as a form of volunteer work. Since volunteer work is considered consensual labour, the labour board does not have or need jurisdiction as one is governing themselves (U.S. Department of Labour). The jurisdiction involved in volunteer work is similar to reproductive labour done by a gestational parent for their own child. Reproductive labour is assumed to be consensual and self- governed thus it is assumed unnecessary for the Department of Labour to protect and enforce reproductive labour standards. Moreover, the Department does not need to enforce how you treat yourself but how one can treat others. One cannot exploit oneself.

The legal regulation and recognition of surrogacy as a form of work is an example of the legal recognition of gestational labour as a regulated form of labour. Surrogacy is not a transaction of a product or organ tissue. Instead, it is often recognized as work and as “labour power, a commodity that is often offered in exchange for a wage” (Armstrong 2022, 173). The immense labour power needed for surrogacy and the toll it takes on the worker is recognized nationally. For example, Louisiana State Law requires surrogates to prove emotional stability to endure their work. Louisiana HOUSE BILL NO. 1102 states that the gestational parent needs to “certify that prior to executing the gestational carrier contract she has

undergone at least two counseling sessions, separated by at least thirty days, with a licensed clinical social worker, licensed psychologist, medical psychologist, licensed psychiatrist, or licensed counselor, to discuss the proposed gestational carrier” (Bishop et al. 2016, 5).

Louisiana State Law regarding surrogacy contracts understands how the gestational parent ought to be in full control over the medical decisions of their body. Specifically, Louisiana State Law declares “that the gestational carrier has sole authority with respect to medical decision-making during the term of the pregnancy consistent with the rights of a pregnant woman carrying her own biological child” (Bishop et al. 2016, 5). Moreover, the existence of state regulation regarding surrogacy laws and social recognition of paid surrogacy proves gestational labour can be compensated and recognized as labour if it involves an employer. What differentiates unpaid reproductive labour, paid reproductive labour, and volunteer work from forced gestational labour is the element of consent. Once it is illustrated that pregnancy can be labour, then non-consensual pregnancy is forced labour.

The overwhelming theme throughout the Department of Labour’s language and conceptualizations of enforceable labour is the level of consent between two parties. While this is not stated by the Department of Labour, the language used creates the notion that labour can only be regulated if it is being enforced by an outside party. This holds as one cannot exploit or force oneself to do something against one’s will. Thus, without the involvement of another actor, all action and labour are considered self-regulating and thus consensual. In terms of pregnancy, the impregnator is not directly involved in enforcing the gestational labour done by the gestational parent and thus not considered an employer. Yet, the gestational parent also lacks a certain level of consent in gestational labour as one cannot necessarily decide to stop being pregnant. One can only stop gestational labour with the involvement of another individual to perform an abortion. Furthermore, one can only attempt to consent to this process during conception. If an individual is non-consensually impregnated, and therefore cannot consent to the process of enduring this labour, this is a completely non-consensual process and forced condition. The

U.S. Supreme Court and Department of Labour ought to recognize pregnancy as a form of untraditional labour due to its enforceability against one’s will.

To prove that forced pregnancy ought to be recognized as forced labour, this paper will illustrate how it can be considered involuntary servitude according to the U.S. Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP Office). The TIP Office uses language from U.S. Department of Justice Chapter 77 of Title 18, known as Chapter 77 offenses to describe modern slavery as “involuntary servitude/slavery or forced labor” (The United States Department of Justice). Involuntary servitude is prohibited under Section 1584 of Title 18, which prohibits holding “a person in a condition of slavery,” which is compulsory service or labour against their will by means of “actual force, threats of force, or threats of legal coercion” (United States Department of State). The U.S. Department of Justice states that an individual in violation of Section 1584 of Title 18 can be fined or imprisoned for up to 20 years maximum, or both. If death, kidnapping, aggravated sexual abuse, attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or attempt to kill results from a violation of Section 1584 of Title 18, the accused can be fined or imprisoned for any term or life, or both (United States Department of State).

Supplementary regulations and descriptions of forced labour illustrate the correlation between gestational labour and forced servitude. The TIP Office states human trafficking occurs regardless of whether the victim was “born into a state of servitude, were exploited in their hometown, were transported to the exploitative situation, [or] previously consented to work for a trafficker” (United States Department of State). The TIP also recognizes involuntary domestic servitude as a form of human trafficking which can occur in the private residence where a domestic worker is not free to leave their employment and is often unpaid. Domestic workers often do not receive benefits and protection––which other groups of workers enjoy––and are often met with abuse, harassment, and sexual and gender-based violence.

This section will explain how the characteristics of involuntary servitude categorize forced pregnancy as forced labour. To deem gestational labour as involuntary servitude it must first be proved that the labour is against one’s will, and then prove there are means of force. The first characteristic is the necessity of consent or the labour against one’s will, causing an individual to be held in a state of involuntary servitude. The most obvious and compelling case for this argument is the case of rape induced pregnancy, which is devoid of any and all consent. In the case of rape, the gestational parent did not consent to the condition of being in labour. Additionally, the gestational parent is forced into such condition by means of “actual force,[or] threats of force” (The United States Department of Justice). The TIP states that an individual can still be trafficked and thus held in a condition of servitude regardless of if they “previously consented to work for a trafficker” (The United States Department of Justice). Therefore, even in a case of consensual impregnation, if the gestational parent decides they no longer want to be pregnant and cannot receive an abortion then it is still considered to be a state of involuntary labour.

The condition of “involuntary servitude/slavery or forced labor” as defined in 18 U.S.C. § 1584 implies an external factor or employer who is holding the individual in this position, hence legal punishment for the crime. The rapist ought to be considered this individual as they are the actor which causes an individual to be trapped in “a condition of compulsory service or labor against his/her will” (The U.S. Department of Justice). Secondly, the state is therefore also responsible for this condition of involuntary labour as they are holding the individual in a state of compulsory labour against their will, if the will of the gestational parent is to get an abortion. The most compelling argument which proves these laws apply to domestic labour is the TIP’s inclusion of involuntary domestic servitude as “a form of human trafficking,” which is when the domestic worker is not free to leave their employment (United States Department of State). In terms of forced labour of a gestational parent, they are not physically restricted to the place of employment or

work, although without access to an abortion the gestational parent is not free to end or leave their position and condition of labour. Furthermore, a gestational parent is never given any form of direct income by a person as they are not technically employed, although this is a part of a larger debate and critique on the nature of capitalist recognition of labour.

To recognize these positions of labour, as defined under Section 1584, “requires that the victim be held against his/her will by actual force, threats of force, or threats of legal coercion” (The U.S. Department of Justice). A position of involuntary pregnancy entails these restrictions by means of state force and restraint. A gestational parent without legal access to an abortion is held against their will in that position by means of actual force as there is no physical way to end their position, physically forcing them to remain in that position. A gestational parent is threatened with force through the physical force of imprisonment if they choose to end their position of labour and, thus, get an abortion. For example, in Texas anyone who performs a successful abortion is guilty of a first-degree felony which is punishable by five to 99 years in prison or $10,000 (Messerly and Ollstein 2022). Although arguing against state punishment being unjust, illegal, or the enforcer of a condition may seem unorthodox, it is nonetheless true. Furthermore, this is not the first case of unjust laws creating unjust or immoral conditions for its citizens, nor will it be the last time feminist scholarship and its citizens fight against marginalization and systemic oppression.

While this does not affect the legality or jurisdiction of the argued laws, the danger and effects of non-consensual pregnancy should not be overlooked. According to Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), 94% of women who are raped experience Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) within two weeks following their assault. Moreover, 30% of women report symptoms of PTSD within nine months following the rape, 33% of female rape victims contemplate suicide, and 13% of female rape victims attempt suicide (RAINN). In 2020, there were 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births, with the mortality rate being 2.9 times higher for non-Hispanic Black women

(RAINN). These statistics are not all encompassing of the harmful effects of pregnancy and forced pregnancy, but they offer a moment to understand some of what is at stake.

The ethical questions that surface regarding forced pregnancy ought to be critically examined. While the overturning of Roe v. Wade allows for the protection of “innocent human life, created in the image of God,” it appears this law is not enforced to protect all lives (General Assembly Kentucky 2023, 1). If forced pregnancy can result in health complications, natural death, and suicide should the state have the right to force these conditions on one individual for the sake of another? While Dobbs v. Jackson contends it is the state’s duty to protect the life and liberty of all individuals including unborn children, in doing so they relinquish the right to liberty of the gestational parent. While all deserve protection to life and liberty, it is not right to intentionally strip an existing individual of such rights, put them in danger, and threaten their life for another.

It ought not be the right of a governing body to declare one life more valuable and worthy of protection than another life. Furthermore, if the federal law still allows capital punishment to be dictated by certain states, then it appears the government does not believe it is their duty to protect all lives. Logic contends the life of a prisoner on death row is essentially a life and alive as much as that of a child. In turn, if the state does not protect all citizen’s lives, as U.S. citizens can be punished by death, it appears the state does not protect life for its innate value nor believe all lives should truly be preserved. If U.S. law protected the innate right to life, as it claims in protecting the unborn, then the state would also prohibit the death penalty.

Furthermore, many states have declared actions causing a miscarriage and thus “causing the death of the unborn child” is murder (United States Department of State). Murder in certain states can be punishable with the death penalty. Should the government operate on an eye-for-an-eye basis? Should those found guilty of receiving an illegal abortion be pun-

ished by death? A governing body which fundamentally lacks intrinsic morals ought not determine the value of one life over another.

The argument that forced pregnancy ought to be considered forced labour will likely receive objections regarding the level of consent involved in pregnancy. Specifically, counter arguments will likely object to the lack of employer or direct enforcer of gestational labour. Moreover, the lack of an individual actor who can be deemed responsible for another’s state of forced pregnancy discredits the argument that forced pregnancy is forced labour. This is likely the most significant reason why it is not recognized as forced labour under the Department of State or Department of Justice. In the case of rape induced conception, the rapist and state are responsible for creating a condition of forced labour and ought to be recognized as administering the means of forced labour conditions.

The jurisdiction of the Department of Labour and boundaries of forced labour ought to be amended to include involuntary forced labour even if there is no employer. 18 U.S.C. § 1584 should be amended to specifically recognize forced pregnancy as labour without consent where the person is held against their will to continue such labour. Regardless of possible amendments, 18 U.S.C. § 1584 ought to be invoked in cases of forced pregnancy to allow the gestational parent an abortion and a means of escaping forced labour. U.S. citizens deserve equal protection under the law from the moment of their conception to the time they become pregnant. It is ethically wrong and illegal to hold any individual in a condition of forced servitude, whether they are pregnant or not.

References

Armstrong, Sylvie. 2022. “Labour Is Labour: What Surrogates Can Learn from the Sex Work Is Work Movement.” Journal of Law and Society 49, no. 1: 170–192. doi:10.1111/jols.12350.

Balka, Ellen. 1991. “Margaret Lowe Benston: 19371991.” Labour / Le Travail 28, 11–13. http://www.

jstor.org/stable/25143505.

General Assembly of Kentucky. 23 RS BR 992, 507 ed., KRS 508.090. Kentucky Legislature, 2023, pp. 1–7.

“Involuntary Servitude, Forced Labor, and Sex Trafficking Statutes Enforced.” The United States Department of Justice, 2015. www.justice.gov/crt/ involuntary- servitude-forced-labor-and-sex-trafficking-statutes-enforced.

Louisiana State, Bishop, et al. HOUSE BILL NO. 1102, ACT No. 494 ed., Louisiana State Government, 2016, pp. 1–17. 2016 Regular Session.

Messerly, Megan, and Alice Miranda Ollstein. 2022. “Abortion Bans and Penalties Would Vary Widely by State.” POLITICO. www.politico.com/ news/2022/05/06/ potential-abortion-bans-and-penalties-by-state-00030572.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. No. 19–1392, 24 June 2022.

“Definitions.” U.S Department of Labour, November 2, 2022. https://www.dol.gov/ agencies/olms/compliance-assistance/interprative-manual/030- definitions#:~:text=%22INDUSTRY%20AFFECTING%20 COMMERCE%22%20me ans%20any,1947%2C%20 as%20amended%2C%20or%20the.

“Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics.” RAINN, www.rainn.org/statistics/victims- sexual-violence. “What Is Modern Slavery? - United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State, 2020. www.state. gov/what-is-modern-slavery/.

About the Author

Lauren Kidd (she/her) is a fifth year Political Studies Major and Philosophy Minor.

Her research interests are: Feminist political philosophy.

Introduction

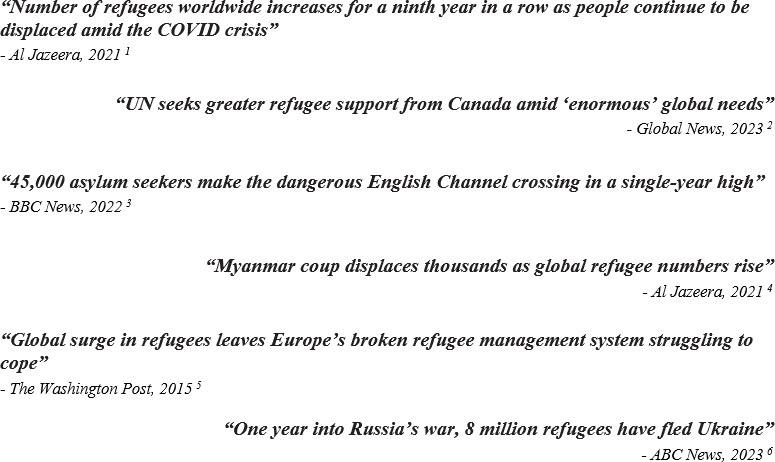

Currently, there are approximately 31.5 million refugees and asylum seekers worldwide (United Nations High Commission on Refugees 2022), a figure which has doubled over the last decade due to political tyranny in Venezuela, Eritrea, and South Sudan, wars in Syria, Ukraine, and DR Congo, and ethnic cleansing campaigns in Myanmar, Afghanistan, and China (United Nations High Commission on Refugees 2023). The growing volume of forced migrants has been met with heightened nationalist and protectionist attitudes, with countries that have previously welcomed refugees now choosing to scale back admissions. In 2022, 940,840 asylum claims were filed worldwide, yet only 21% of claimants were granted asylum (United Nations High Commission on Refugees 2022). The same year, the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) identified roughly 20 million displaced peoples as “in need of foreign resettlement, but less than 1% actually received it” (2022). States have also ramped up efforts to deter prospective asylum claimants (Bishop 2020, 2096), including aggressive anti-immigrant social media campaigns, deporting claimants to a third-party country for indefinite detention

(McDonnell 2021), and family separation policies, under which asylum seekers’ children are seized and detained separately or adopted out (McDonnell and Merton 2018).

States have defended these policies by arguing that the powers to enforce their borders and determine who is admitted to their political community are constituent to their sovereignty, and that without these powers, the modern state structure would collapse. Many theorists who endorse the conventional view of border sovereignty already concede that refugees and asylum seekers have a special moral claim to admission; however, they maintain that the sovereignty principle gives states broad discretion in how they meet their obligations to refugees. In this paper, I challenge that a liberal understanding of distributive justice not only establishes a duty for states to admit refugees and asylum seekers, but also constrains the criteria that states are morally justified in using to decide which claimants they will accept.

I begin by situating the issue of refugee admissions within the wider conventional paradigm debate over the extent of states’ rights to control immigration and impose selection and exclusion criteria on prospective immigrants. Here, I argue that while the principles of the Westphalian system give states broad discretion over admissions, the legitimacy of those powers is dependent upon states fulfilling a responsibility of reparation to people arbitrarily and critically harmed by the Westphalian system’s random allocation of citizenships at birth. In the case of forced international migrants (refugees and asylum seekers), reparation necessitates admission to a political community which will secure their basic human interests. In Section two, I consider proposed limitations on states’ duty to admit refugees. Distinguishing between morally important interests and vital interests, I defend states’ right to limit admissions when necessary to

protect members’ vital interests, but argue they are not morally justified in excluding forced migrants for the sake of preserving lesser freedoms and privileges for members. In Section three, I discuss how the distributive justice view constrains the criteria that states are justified in applying to triage admissions when the volume of forced migrants seeking admission exceeds the state’s capacity. I ultimately conclude that a liberal understanding of distributive justice precludes triaging based on a state’s non-essential self-interests; however, relationships of moral significance between a forced migrant and the prospective receiving state can create a positive duty to prioritize specific individuals for admission.

Theorists of the conventional paradigm see states as political communities, bounded by relationships of reciprocity, shared interests, and a common identity. In liberal theory, political communities must be self-determining because personal liberty requires that members of these communities be able to pursue and actualize their collective interests. Conventional theorists argue that for a community to be meaningfully self-determining, it must be free to choose who can immigrate into the association. Wellman, for example, likens political communities to clubs (2008, 110). Clubs are voluntary associations of members pursuing a specific purpose. If current members are unable to filter prospective members, new members with different interests might reshape the association and undermine its initial purpose. Beyond ensuring members’ security, theorists vary in their interpretation of what the ‘initial purpose’ of a political community is. Walzer views political communities as vehicles for protecting the distinctive culture of members. He argues that protecting this culture necessitates broad leeway for members to select people they deem culturally compatible, based on their “shared understandings” of what defines their culture (language, ethnicity, political ideology, etc.) (1983, 40).

Liberal nationalists like Miller focus on political communities’ role in facilitating shared identity and social solidarity, which are preconditions for liberal institutions (Miller 2005, 200). From this stand-

point, states are justified in limiting immigration to allow the culture and resource stocks to adapt. Liberal nationalists argue that without this control, the influx of immigrants would overwhelm state infrastructure, diminish quality of life and social solidarity, and collapse the welfare state (Miller 2005, 201). Among conventional theorists, there is a consensus that it is an unjust violation of moral equality to exclude prospective immigrants based on immutable characteristics. However, they argue since the state has no obligation to admit immigrants, if they choose to do s they ought to be able to select immigrants whose presence imposes the least cost on the existing community, and whose skills will help them integrate.

The moral status of forced migrants is a point of contention in the conventional paradigm. Some theorists advocate that considerations of distributive justice give refugees a special claim to states’ assistance. Waltzer, for example, describes states as “clubs with family characteristics;” members can feel compelled by humanitarianism to aid suffering strangers (1983, 42). In line with Rawls’ Principle of Mutual Aid, he suggests that aiding refugees by admitting them becomes a duty when a state can do so without facing costs (Waltzer 1983, 33). Miller similarly argues people deprived of their basic rights have a justice-based claim to resettle to a new state, yet this claim is a “theoretical right, dependent on a state’s cooperation which cannot be forced” (2005, 196). In this view, refugees are entitled to admission in a state where their basic needs can be met, but no state has a specific duty to aid.

More extreme statists eschew the idea of a duty to admit refugees, arguing that this wrongfully violates the existing community’s right to self-determination. Ekins argues that a state ought to only concern itself with its members’ interests, and that its members have the ultimate claim on state resources because their labour sustains the state (2019, 41). Therefore, a state cannot have a duty to admit refugees, because this would impose a cost on members by diminishing their share of resources. Wellman builds on this, arguing if states have any duty to aid refugees, they must do so

in a way that does not limit their members’ resource shares or freedom of association; his proposed solution is military intervention in the refugees’ origin states (2008, 129). The common thread among these theorists is that they treat the duty to aid refugees as conditional on whether it can be fulfilled without impacting members.

I argue these views assign excessive moral weight to members’ freedom of association, and this causes them to treat sovereignty over territory as no-strings-attached right of political communities. They fail to recognize that the legitimate exercise of sovereignty requires fulfilling certain responsibilities to non-members. We can conceive of the Westphalian state system as a kind of social contract between political communities designed to ensure distributive justice: each community has the exclusive right to appropriate a given piece of land to provide for their members’ basic needs, and all people are entitled to membership in a community which is responsible for meeting their needs (Carens 2013, 203). The power of territorial sovereignty was designed to fulfill the first of these objectives, and the practice of allocating citizenship at birth was designed to fulfill the second.

In this system, assigning birthright citizenship should not be seen merely as a process of one state “recognizing the person as its own” (Ekins 2019, 41). It also implicitly entails all of the other states recognizing that person as “not mine,” renouncing association between their political communities and the individual, and discharging their share of collective responsibility for that person’s welfare to the one designated state. The moral rationale behind this arrangement is that it will facilitate distributive justice; for the sake of efficiency and fair access to resources, each person is given an entitlement to the protection and resources of one state (Carens 2013, 20). The implication is that states are only morally justified in exercising their sovereignty to reject membership-association with an individual if doing so promotes distributive justice.

In this view, whether a state can control immi-

gration to promote members’ freedom of association depends on whether this can be done in a manner consistent with distributive justice. I argue that in the case of voluntary migrants, it can. Distributive justice does not require that everyone have identical resources and opportunities, only that everyone has sufficient resources to live an autonomous and dignified life. As Miller writes, “what a person can legitimately demand access to is an adequate range of options to choose between to fulfill their generic human interests––occupation, religion, cultural activities, marriage partners, and so forth” (2005, 196), in addition to the core human rights that membership in a political community is meant to provide: personal security, kinship networks, legal equality, and the ability to participate in political and social life. We set the threshold at “an adequate range” because it would be logistically impossible to offer everyone every opportunity, and because people are not meaningfully harmed by lacking one option if they have a range of other viable ones. Consider a hypothetical: a person requires a car to get to work, and the options available are a Toyota, a Ford, a Honda, or a Nissan. Since any of these options could satisfactorily fulfill the person’s transportation needs, we don’t consider it a problematic limit on their freedom that they don’t have a local Kia dealership. Similarly, people whose fundamental interests and human rights are satisfied in their origin society have a distributionally fair share of opportunities and resources. They may still wish to migrate to pursue opportunities that they prefer elsewhere, but “their desire is not one that imposes any kind of obligation on others to meet it” (Miller 2005, 194). There is no clear reason why their individual preference to be admitted to another state should be given more moral weight than that political community’s freedom of association. Therefore, a state choosing to limit admissions of voluntary migrants is compatible with distributive justice, and a morally permissible use of sovereignty.

Forced migrants, however, are another matter. The practical distinction between forced and voluntary migrants is murky, but for the purposes of this argument, a migrant is ‘forced’ if their origin society cannot or will not ensure any one of the vital human

interests outlined above. As Carens argues, “states are morally obligated to take these sorts of fundamental interests into account in their citizenship policies” (2013, 25). It is not sufficient that forced migrants theoretically have a state designated for meeting their needs; distributive justice demands the substantive fulfillment of these interests. This requires resettlement to a safe state, because the alternatives—sending development aid to the inept/corrupt government of a failed state, or warehousing people in refugee camps––cannot provide these forced migrants a comparatively decent degree of autonomy or quality of life (Souter 2014, 337; Walzer 1983, 48). Whether for the sake of their human rights or their very survival, forced migrants’ vital interest in being admitted to a new political community gives them a moral claim to admission that outweighs members’ lesser claim on freedom of association (Oberman 2016, 35).

Moreover, I suggest states have a duty of restorative justice to admit forced migrants. The citizenship a person is dealt upon birth is a determining factor in the political rights, economic mobility, and social security they will have (Carens 2013, 226); therefore, through the practice of collectively assigning citizenship, all states in the international system are responsible for shaping the person’s quality of life and opportunities. These individuals are forced to migrate because they were allocated to a state which failed to secure their vital human interests; this can be seen as an injustice perpetrated against them by the Westphalian state system, and as Carens argues, the co-creators of an institution have a shared responsibility to correct its failures (2013, 196). Forced migrants represent a failure of the state system to deliver the distributive justice it is premised on. If states refuse to fulfill their responsibilities as authors of this system and close their borders to forced migrants, they forfeit the right to exercise the powers they receive by participating in the system, chief among them their power of territorial sovereignty.

Miller partially addresses this line of argument, acknowledging that forced migrants ought to be admitted to a safe state, but argues that it does not follow that any specific state has a duty to admit them. He states what forced migrants are entitled to is a choice between the states willing to accept them

(Miller 2005, 202). The flaw of this argument is it rests on the assumption that there will be states willing to admit the forced migrants. Let’s entertain Miller’s hypothetical for a moment: imagine a state(s) is eager to accept any and every forced migrant who possesses a legitimate claim to resettlement, and is capable of securing their rights and vital interests. This would be lovely, and wholly compatible with distributive justice. However, Miller’s assumption doesn’t square with the reality of millions of forced migrants in need of resettlement, and the decade-long trend of less than 1% receiving it (United Nations High Commission on Refugees 2023).

Miller is correct that the distributive justice argument doesn’t prescribe a duty for any specific state to assist specific forced migrants, but it does establish that all states capable of supporting some forced migrants ought to be willing to admit. To understand why distributive justice requires this, let’s consider what happens when states capable of admitting forced migrants refuse to do so:

“When a million asylum seekers arrived in the European Union in 2015, there was a backlash. Countries built walls, refused to accept refugees, […] leaving them in a state of protracted legal and social limbo. The authorities refuse to regularize them or to grant them any kind of legal status. These desperate persons live in substandard conditions, completely excluded from society, lacking the means to meet basic needs such as shelter, food, health, or education. They are deprived of any opportunity to live in dignity” (Kakissis 2018; Muižnieks 2016).

Not only do these border closures harm the asylum seekers, but they also force a pile-up of people in the states bordering their origin country. Turkey, Pakistan, and Ethiopia are prominent examples of border states overwhelmed by forced migrants who had planned temporary stays, only to find the doors to their ultimate destination slammed in their faces. Consequently, these states face overcrowding, strained infrastructure, and bureaucratic overwhelm as they bear the brunt of refugee crises. In this way, other states’ failure to accept a share of forced migrants can be seen as an act of distributive injustice to these border states

(Ogurlu 2019). The Westphalian system is “premised on the equal rights and obligations of all states,” (Carens 2013, 227) and forcing border states to bear the financial and social toll of an influx of vulnerable people represents a shirking of obligations by the rest of the system. As Carens argues, “it is never enough to justify a set of social arrangements governing human beings by say that these arrangements are good for us, without regards for others, whoever the “us” may be––we must appeal to arguments that explain why the social arrangements are reasonable and fair to everyone who is subject to them” (Carens 2013, 227). Therefore, while there may not always be a logistical need for all states to accept forced migrants, all states capable of supporting forced migrants must be at least willing to admit a proportionate share of them.