Foreword

I’m writing this while watching a TV show from 2012 that only got one season. Thankfully, Quilt Mini has lived to see another year.

FOREWORD

This printed phenomenon exists in whole because of the extraordinary people who dedicated their days to ensuring its fruition. My Co-Editor-in-Chief, Sam Goodale, and I could not be more thankful for our editors, illustrators, layout designers, event coordinators, website manager, and of course, esteemed authors. Your work and effort are invaluable–we are so honored you shared it with us.

Welcome to Quilt Mini 2. Enjoy.

Much love, Fiona Mulrooney

Editor’s Note

Authors in this volume include staffers at Quilt. Our selection process demands anonymity, and stipulates that anyone who recognizes the author of the work leaves the room and not partake in the deliberation process. We wholeheartedly stand by this method, and believe, in full, that the work showcased here is the best of what we received.

In fact, many members–including myself–have been rejected by Quilt in the past. Our editorial boards are a picky bunch. It’s why we hired them.

HOW I STARTED

Faith Brooks

When I was born I changed my mother’s hair

(What happens to a body is a daughter’s fault).

I drank salt water mixed by a propellor

On the back of a boat, Ate grapefruit my grandfather bought accidentally,

Took a 500 a month stipend

And some bullet points,

Pushed on the doors I knew would get me out of there.

I sent you four rough drafts on a Wedneday morning (Wednesday being the only day things happen to me), Cut out my larynx and replaced it with yours, Braided my veins Into twisted irons Licked up the rust and Pulled myself (On my stomach) to the water.

7

Isn’t it pretty?

Sifting through Shells, muscles, bones the ones taken out of other backs buried in the sand of the before -

I hold the name in an open hand, I wear it like a curse, Like a conversation starter about God, I wear it like a religion I don’t practice, I wear it like a gift my parents gave me

Without ever being able to give it up.

You wonder how I started?

I followed the red ribbon here,

It’s stained beneath my fingertips.

8

In the Language of Tongues

Karen Au

My first is perhaps the most foreign, yet it is the one of home. Cantonese: she lights the path forward, a promise of return, the motherland beckoning us. She brings home wayward sailors paddling peeling kayaks packed with families, Canadian-born. Almost at the shore, upset, upstart, unsure, the smallest wave snatches me from my oar pulling me into the sea so I can ask my kindergarten teacher to go to the bathroom. Now at home I speak Chinglish, and it’s a rickety raft I can barely get to shore with. I’ll arrive wind whipped and soaked, adding salt to the sea, bleeding.

9

The second language to conquer my tongue laps at the shore of consciousness as I stumble through shifting sand. The maple leaf is branded on my chest, apparent under the dripping translucent shirt, buttoned to the top.

I might have been born here, but my way of speech is a barnacle, clinging to the bottom of a hull that has traversed many seas. My English is flavoured as if I had washed ashore with spice laced into my back, tea stitched into my fingernail beds. When I expel the water in my chest, my tongue gleams of the sky, limitless.

10

I’ve been told I speak with the cadence of monarchs and though Victoria ground opium laced teeth into her land, my grandmother does not speak the colonial language. Her tongue sings in the water-eroded cave of our ancestors. My mom might have been raised to place “u” in her words, but she lives in her mother’s warm mouth and dances in red silk with scalloped edges, golden with fireflies. She emerges when Jessica calls or when the mailman asks her to “sign here,” but the fabric still pools around her, and skeleton fireflies blink in her hair.

I can see, with each step towards the water, the strength she had to leave her home, lighting my own with her flickering tongue.

11

12

Do not speak of it.

We know what happens When things are spoken of.

EVERGREEN

Victoria Heath

It is the first Winter with you.

We buy a Christmas tree, a real one, the type my mother would never let me have as a child. We position it in the corner of the dining room and spend the rest of the evening drinking white wine and adorning its branches with baubles. As you stand to put the star on the top (not an angel, because you always had stars as a child and I am happy to continue this tradition), the needles cascade onto the carpet like green flecks of snow. I don’t want to vacuum them up, even if this means we will be picking green from our socks and hair for the next few weeks. On Christmas Day, we stifle our laughter as my mother pulls a pine needle out of her glass of prosecco. Weeks later, I keep recalling this moment in fits of giggles. You ask why I am still not over it, and I want to say that it makes me happy to see her as the butt of a joke for once. But instead, I tell you that some things are just funny like that, and all the potential conversations about imperfect families remain shut.

It is the first Spring without you.

My mother texts me once during Spring, one long message to tell me exactly which flowers I should start planting; that avocados are the new superfood, and that smearing Amazonian mud clay on your face is the latest form of self-care. In the weeks following her message, the flowers in our garden begin to crop up between mounds of melting snow. Next to the budding flowers stands our Christmas tree that we dragged through the house and into the garden. You wanted to have the same one each year. A tradition, you laughed as we dug through the frost-covered soil in January. Now, I pluck a nearby budding flower from the soaked ground, roll it in my palms until the petals bleed their pinkness onto my skin. Watching its pigment burst all over my hands, its seeds sputtering out onto my palm. I throw the seeds into the ice.

It is the first Autumn without you.

15

From the kitchen window, I watch as the leaves turn into red and yellow mush in the rain - the Christmas tree the only green thing left in our garden. I find the number for a local gardener in the newspaper, calling him for a quote to get rid of it. He offers to do it for an obscene amount of money, so instead I pay twenty dollars for some second-hand blinds and fit them over the little window directly behind the kitchen sink. This way, I can wash the dishes alone.

It is the first Winter without you.

I hold on to my own hand this year, buried inside the kangaroo pocket of my hoodie, the curve of my fingernails pressing against my palm. The Christmas lights of stores heave their red and green fluorescence at me, the whine of Christmas music inescapable in every crevice of the town. So, I find myself receding away from the festivities, spending most of my winter in the house as snow falls on everything like pepper.

16

On the day before Christmas Eve, my mother shows up to the house with a huge cardboard box in her arms. She arrives like a flurry, immediately pointing out the complete lack of anything!!! on the living room walls where I had spent the last several weeks taking down some old photos of us. She drags the tree across the floor to the dining room, disturbing the grooves in the carpet I had made with the vacuum. The tree will go up whether I want it to or not, so I don’t bother to lift myself off the sofa.

The sound of a knife dragging through cardboard. I lean forward, peering through to the dining room as she puts up the Christmas tree, fanning out and fluffing its plastic branches. She says something about how beautifully big it is, and I murmur a noise that sounds like approval. We exchange a few words as she decorates the tree alone, things about her job and my job, the fact it’s getting dark early and the closure of the local mall, all topics that we rotate between as if it were a script. Just when I think she is about to leave, could you put the star on the top comes out of her mouth. It’s a barely audible request, a little whisper of a thing. I open my palm out to her like a clam shell and she places the star into it, and I scrape a dining chair across the floor to the foot of the Christmas tree. Standing on top of the chair, I steady myself and put the star into the top of the tree, artificial pines digging into my fingers as I jam it in place. From this height, I look down at my mother, noticing the smallness of her frame, her hunched shoulders, the smile forming across her mouth at the sight of the completed tree. She has a lipstick smear across her chin, but apart from this she looks perfect, doll-like happiness.

Through the glass door behind the tree, a flurry falls outside, snow pulsating out of the clouds like the smattering of icing sugar over a cake. The whole world bathed in whiteness: white houses, white-topped fences, white clouds bursting at the seams. And yet amongst the whiteness, I made out the silhouette of our Christmas tree in the darkness. Unattended to for almost a year, covered in snow. Away from the house that was once ours and now was just mine, lonesome in the bitter night frost, our unchanging, undying Christmas tree.

17

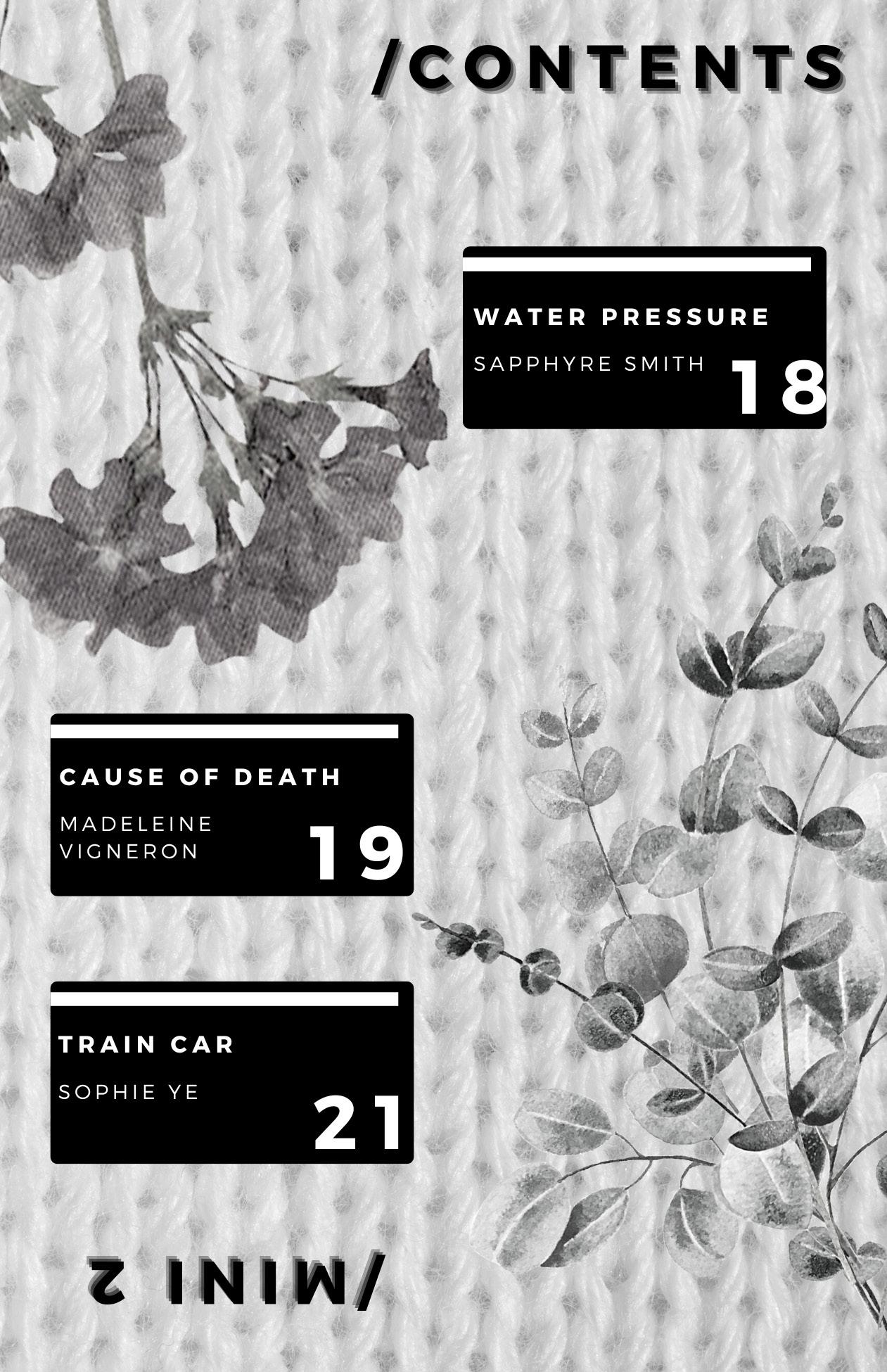

Water Pressure

By Sapphyre Smith

you turn your head in the shower curve your neck, just so and let the water run down your cheek like a hand cupping your face a palm thrumming with the heartbeat of summer rain.

this is the part where you forget float on steam and the promise of a train ride home to a bed that knows the shape of your body and footsteps you recognize before the knock on your bedroom door

it’s warm and soft, and vapor curls lightly around you crowning your hair with misty feathers you imagine yourself there not here

and let rivulets rock you into a hazy standing sleep a chug, a switch, the pressure changes –

and now you’re standing in cold condensation.

icy fingers dig into your scalp, shock the breath from your lungs you let the frigid radiation crystallize your blood, let it drive your home-bound lifeboat to a frozen grave because now not even water wants to hold you and there is no one here to ask if you need help to change the pressure.

it pushes you away but you stay because the cold brings out the blue in your veins, the pebbles in your skin it holds even as it shoves, and you tell yourself it’s better than nothing.

18

CAUSE OF DEATH

Madeleine Vigneron

After they fish the waterlogged corpse from its resting place at the bottom of the lake, they arrange it on a table like a funerary slab. The coroners detach the metal hooks from the dredging net and unwrap the mesh from the cold body. The ragged remains of clothing, drenched and muddy, are carefully sliced and peeled away, and they wash the silt and seaweed off her clammy flesh. One picks algae from her hair, disappointed that it falls in thick matted clumps rather than floating, long and light, about her head like Ophelia’s. The body’s surface, too, is a disappointment. It is not pale and marble-smooth to the touch—the lovely lines are disrupted by bloating. The skin is pebbled and discoloured; visibly covered in short, dark hair. That is, where it has not been bitten and torn away from its time on the lakebed. They might conclude, if they are particularly adept, that as the body sank downward, it was curiously nibbled by small fish darting in schools through the sun-warmed water. They might notice from the shapes of these incisions that she thrashed, not against death but against the indignity and discomfort as she reached for it. But that conclusion is unlikely, as those minor bites are hidden by the larger chunks of tissue ripped from the water-softened body by those creatures at the bottom of the lake, by which point she had learned—or at least grown tired enough— not to struggle. Most likely, they will conclude she went to the feast willingly.

When the knife meets flesh, it yields quickly to the dull metal, spilling turgid lake water rather than blood. The muscles of the thigh are saturated, soluble; slowly drowning as the lungs did during her descent. They discuss whether this leg might have carried her to the cliffside, walking purposefully as a bride to the altar, or whether she might have been pushed by a stranger, suddenly and violently. Ultimately, this part of the corpse is too waterlogged to meaningfully study, a thin wrapper of mottled flesh broken easily, like the skin of a water balloon.

19

They move on to the head. A long incision across the hairline, and they peel back the scalp from the white bone of the skull underneath. This, at least, is as hard and white as expected. As the serrated saw rasps through the chalky barrier, the one not holding the saw remarks that he always tends to see bone as less alive than the rest of a body. Sure, he can imagine life coursing through the soft parts. But, perhaps from all the skeletons he’s handled, he imagines the hard bone as a frame for the soft living matter rather than the living matter itself.

“Even the soft parts of this one are dead,” says the one with the saw, and he continues his work.

When they finally break through, cracking the skull open like an egg, it too has been filled with filmy lake water, seeping into the skull alongside the spinal cord. The brain sloshes about in its fishbowl, fissures and sulci unfolding and unfurling, surrendering to its surroundings just as easily as the leg did. It is impossible, in this half-decomposed state, for the brain to provide any meaningful information about how the body ended up underwater. It is hard enough to tell where the girl ends and the corpse begins; perish the thought of how the girl ended and the corpse began.

A vertical cut down the middle of the chest; the ribs snap away like decaying twigs. They peel away the flaps of skin and fascia and secure them to the side with hardy metal clamps, petals of tissue opening up like a flower. They try to carefully dissect the organs, but each one dissolves into the soup of viscera.

At the centre of the corpse is a blackened cavern where the heart should be. This, at last, is something that makes sense. A flaw at the girl’s core; scorched evidence of a blaze burning self-destructively through flesh and bone. The equilibrium makes a poetic sort of sense; the fire inside her sought out enough water to pacify it. This was less a tragic death than an inevitable one.

They record the incident as a death of natural causes: the girl’s own nature and of the nature of her surroundings. One of them carefully cleans his blades, and the other hopes their next corpse will be more beautiful.

20

Be Here With Me on this Train Car Seat For Just Three Hours

By Sophie Ye

By Sophie Ye

The woman two seats down with her slim cigarette is laughing into her phone, somewhere a phonograph plays a twinkly tune—How’d that get in here?—And the train, which is a living machine, thunders north. It’ll take us to where we need to go. Right now, we are nowhere at all.

I have a lot to tell you. (But first you break your scone into pieces, buttering each one before popping it into your mouth.) Here’s something: the idea of peace rips me apart. I ask you: Can you imagine walking and having an identity, or knowing desire, or being truly okay with the fact that nothing ever stays the same? and—Where are we going, again?—I tell you: Recently I feel removed from myself.

21

So yes, I’m in poor health, but it could be worse. I could be inconsolable. I could not see the green-gray fields on those perfect off-kilter mornings but I do, and the fog that slithers between the trees is always gone by the time you open your eyes.

But anyway, tell me what you see when you look out the windows. Even as the world is rushing by, describe it to me as though we’re the only people walking through it, taking our time. Sun-washed red upholstery, the maple wood table between us, and the faint smell of coffee beans. This rickety chandelier that might fall on our heads and the stained carpet beneath our feet.

I like watching you lift your teacup to your mouth, sipping, looking right at me. You pose a simple question. Did I get that right? I don’t even need to try to love you.

22

Foster Mcaffee, Photography

By Sophie Ye

By Sophie Ye