VII FORUM QUALIVITA Siena, 5-6 december 2025

The Green Paper on the future of Geographical Indications, presented at the 7th European Forum on Food Quality in Siena, is a strategic policy document developed through the collaboration of the main international organisations of the GI system – oriGIn, oriGIn EU, Origin Italia, Origen España, oriGIn France and Qualifica-oriGIn Portugal – with the scientific and methodological contribution of the Fondazione Qualivita . Published only a few months after the entry into force of Regulation (EU) 2024/1143, it puts forward a shared vision for the implementation phase of the European reform, offering a unified interpretation of the challenges that the PDO and PGI systems will have to face in a rapidly changing global context: ecological transition, digitalisation, online protection, and the evolution of international markets.

Geographical Indications have established themselves in Europe as one of the most effective tools for rural development: they generate economic value, protect landscapes and traditional knowledge, and strengthen social cohesion and territorial identity. For this reason, today GIs must be fully integrated into the framework of the EU’s agricultural strategy and the revision of the CAP, not as an accessory measure but as a structural lever for competitiveness, sustainability and quality. Their nature as collective assets – built on shared rules, controls, transparency and a link to origin – makes them one of the EU’s most successful systems: capable of guiding supply chains towards more equitable and environmentally responsible practices, safeguarding agricultural biodiversity, improving the trade balance, and attracting investment, qualified employment and responsible tourism. This Green Paper aims to indicate the policy choices now needed to consolidate and expand this success: coherent integration

of GIs into CAP instruments, strengthening the governance of Consortia and the competent public authorities of Member States, support for innovation and training, and protection in international markets. It is time to elevate GIs to a strategic infrastructure for the rural Europe we want: competitive, inclusive, and sustainable.

Presented as a collective contribution from the production sector, the Green Paper marks a political milestone: it offers the European Union a platform for reflection on future quality policies and reaffirms the central role of GIs as a strategic infrastructure for the rural Europe we want – competitive, inclusive and sustainable. From this stem clear operational choices: integration of GIs into CAP instruments, strengthening the governance of producer groups, support for innovation and training, and effective protection in international markets.

Cultural and scientific organization dedicated to protecting and enhancing PDO, PGI and TSG products.

Association of GI Consortia, bringing together 90 PDO/PGI italian product Consortia.

A global alliance of Geographical Indications representing 700 GI associations and institutions in 40 countries.

Brings together the European community of GI stakeholders, including national organizations and producer groups.

Association bringing together producer groups of French Geographical Indications.

Spanish Association of Designations of Origin that brings together Spanish PDO and PGI producers.

Association that promotes and protects Portuguese Geographical Indications products.

Context and regulatory evolution in Europe

Geographical indications are distinctive signs that identify products originating from a specific area when their quality, reputation, or other characteristics depend on that origin; they are internationally recognised as intellectual property rights.

Most countries protect them as autonomous rights through sui generis systems, which ensure stronger protection of the names and greater involvement of producers in the recognition processes. Beyond the legal dimension, GIs are tools for inclusive and sustainable local development for producers and communities. There are approximately 18,000 names protected as GIs worldwide.

Main international organizations in the GI field:

WIPO: The World Intellectual Property Organization: an international GI registration/protection system now covering 70 countries.

FAO: The UN Food and Agriculture Organization: promotes Geographical Indications as a tool for sustainable development in agriculture.

WTO: The World Trade Organization: administers the TRIPS Agreement, which sets minimum standards for GI protection worldwide.

In Europe, Geographical Indications are an intellectual property tool designed to protect products whose quality or reputation essentially depends on their territory of origin. In the agri-food sector, they include PDOs and PGIs for food and wine: for PDOs, the entire supply chain takes place within the designated area; for PGIs, it is sufficient that a substantial stage of the process – or a significant component of the raw materials – originates there, ensuring a genuine link with the place. For spirits, the EU uses the GI category, which similarly protects the connection between quality and territory and is now integrated into the new European GI framework. Completing the system is the TSG, “Traditional Speciality Guaranteed”, which does not protect a geographical area but enhances codified recipes and production methods. Beyond agri-food, the European Union has introduced GIs for craft and industrial products (such as glass, ceramics, cutlery, textiles), extending protection to local manufacturing knowledge and territorial production ecosystems. Together, these quality pathways make up the European architecture that protects typical products, supports local economies, and provides consumers with a clear compass of authenticity.

3,484

3,751

The European evolution of GIs is the story of an idea that became a mature public policy: protecting the bond between product and territory and turning it into economic, cultural, and civic value. Since 1992, when the EU established the PDO and PGI schemes, “quality” has entered fully into the architecture of agricultural policy. Under Franz Fischler a CAP took shape that rewarded origin, know- how and territorial reputation; under Mariann Fischer Boel , Europe opened to the world, launched the Green Paper and laid the foundations for the “Quality Package,” conceiving GIs as tools for competitiveness and rural development. The Dacian Cioloș season consolidated the system with Regulation 1151/2012, ex officio protection and production planning for PDO cheeses, recognizing Consortia as actors of economic governance. Then Phil Hogan and Vytenis Andriukaitis strengthened controls and consolidated the international projection with accession to the Geneva Act, turning GIs into a shared global language.

In recent years the system evolved further. In 2023, through an initiative of Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton, Regulation (EU) 2023/2411 established craft and industrial GIs, extending the protection model beyond agri-food and valorizing European manufacturing under EUIPO’s coordination–an official opening toward a “cross-sector quality” concept between agriculture and industry. In 2024 came the decisive step with Regulation (EU) 2024/1143, led by Commissioner for Agriculture Janusz Wojciechowski and rapporteur Paolo De Castro: a true consolidated text that for the first time regulates food, wine, and spirit drinks in an integrated way, introducing principles of sustainability, education, tourism, and digital protection.

EVOLUTIONARY VISUAL SYNTHESIS

PHASE

MODERNIZATION

Wojciechowski

TOURISM & SUSTAINABILITY Paolo De Castro (rapporteur)

VALORIZATION

1992-2004

Franz Fischler FOUNDATION

Reg. 2081/92

2014-2019

Phil Hogan

CONSOLIDATION

Reg. 2019/787

2004-2010

Mariann Fischer Boel

INTERNATIONALIZATION

Reg. 510/2006

2010-2014

Dacian Cioloș

CODIFICATION

Reg. 1151/2012

2020-2024

Janusz Wojciechowski Paolo De Castro (rapporteur)

MODERNIZATION TOURISM & SUSTAINABILITY

Reg. 2024/1143

2024-2029

Christophe Hansen

VALORIZATION

Agriculture Commissioner: Franz Fischler

• Reg. (EEC) 2081/92 – First EU framework for food PDOs and PGIs.

• Leads the consolidation phase of the MacSharry reform and promotes quality policy as a pillar of the CAP.

• Introduces the first unified protection for PDOs and PGIs, based on the link between product and territory.

• Political momentum: launch of the “From quantity to quality” strategy, recognising designations as a tool for rural development.

• Also begins preparatory work for the 1999 Wine CMO (Reg. 1493/1999) , the first attempt to harmonise terminology between the wine and food sectors.

Agriculture Commissioner: Mariann Fischer Boel

• Reg. (EC) 510/2006 replaces 2081/92 → opens to third countries: non-European Geographical Indications can now be registered in the EU register.

• Launches the Green Paper on Agricultural Product Quality (2008) and the Communication on Agricultural Product Quality Policy (2009): - pan-European consultation on food quality; - political impetus for the “Quality Package”.

• Reg. (EC) 479/2008 – Wine CMO: formally introduces PDOs and PGIs in the wine sector as well.

• Political vision: create a “European quality brand” , with harmonised logos and international protection.

Agriculture Commissioner: Dacian Cioloș

• Completes the “Quality Package”:

- Reg. (EU) 1151/2012 unifies PDOs, PGIs and TSGs in a single text;

- introduces ex officio protection and optional quality terms (“mountain product”, etc.);

- strengthens the link between GIs and rural sustainability.

• Manages the Milk Package (after the 2009 crisis):

- introduces production planning for PDO cheeses and PDO hams, later incorporated into Article 150 of the Single CMO ( Reg. 1308/2013 ).

• Coordinates the Single CMO 1308/2013, which definitively integrates wine GIs into EU common law.

•

Agriculture Commissioner: Phil Hogan

• Reg. (EU) 2017/625: reform of official controls across the entire agri-food chain, including PDO/PGI/TSG.

• Reg. (EU) 2019/787: new framework for spirit GIs.

• Decision 2019/1754 + Reg. 2019/1753: EU accession to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement (WIPO) → international recognition of GIs.

• Political orientation: strengthening the “ export of values ” and the multilateral dimension of GIs in free trade agreements.

• EU–Canada Agreement (CETA) – protection of 170 European GIs (2017).

• EU–Japan Agreement (EPA) – protection of over 200 European GIs and over 100 Japanese GIs (2018)

Agriculture Commissioner:Janusz Wojciechowski

Relatore Reg. 2024/1143: Paolo De Castro (TOURISM & SUSTAINABILITY)

• Reg. (EU) 2023/2411: new regime for craft and industrial GIs (managed by EUIPO, applicable from 1 December 2025).

• Reg. (EU) 2024/1143: Single European GI Code for food, wine and spirits → repeals 1151/2012 and amends 1308/2013 and 2019/787.

- Introduces tools for sustainability, Turismo DOP, use as ingredients, online protection, and domain names .

- Strengthens recognised producer groups and collective management.

• Delegated and implementing regulations 2025/26 and 2025/27: complete the new implementation framework.

• Political vision: integrate GIs, environment and digital policy into the “ Farm to Fork” strategy and the EU green transition.

• EU–China Agreement – protection of 100 European GIs and 100 Chinese GIs (2020).

Agriculture Commissioner: Christophe Hansen

In progress:

• Implementing regulations for Regulation (EU) 2024/1143

• Adoption of EUIPO guidelines for trademark registration.

• New trade agreements (Mercosur and others).

• European Action Plan on Geographical Indications.

Updated 14/11/2025

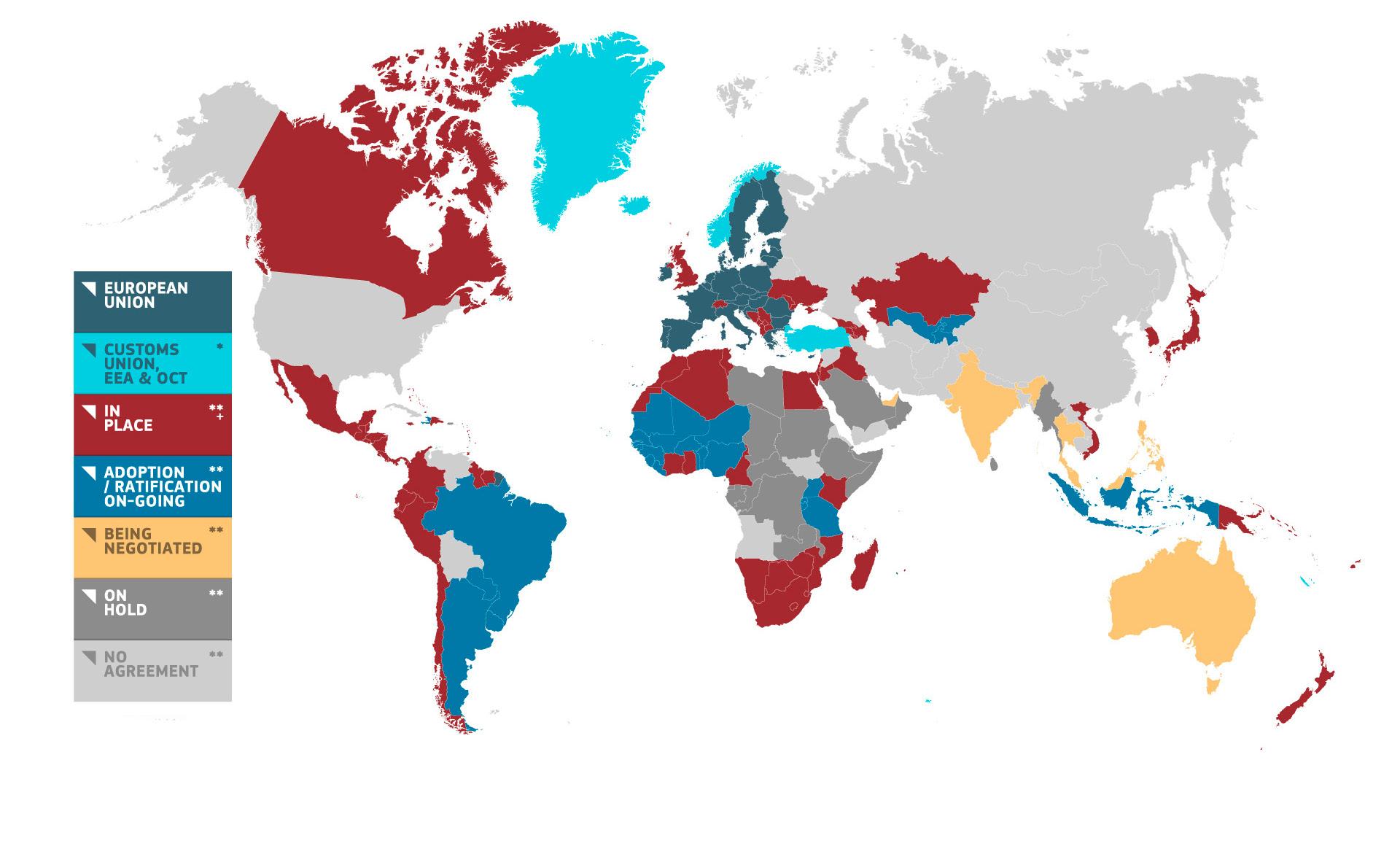

* European Economic Area (EEA) / Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT).

** Free Trade Agreement (FTA), Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA), Partnership and Co-operation Agreement with preferential element (PCA).

+ The updated agreements with Tunisia, and Eastern and Southern Africa are currently being updated; the updated agreement with Chile is under ratification. The DCFTA with Georgia does not apply in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Union concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The future of Geographical Indications

Geopolitical conflicts, commercial instability and the concentration of resources are redefining the logics of food globally. In this context, Geographical Indications represent a network of micro-sovereignties capable of ensuring productive diversification and stewardship of local resources. GIs can become fundamental tools for building a new European model of food security and justice. As a democratic and participatory model, European GIs also play a central role in supporting marginal areas and territories with development gaps, helping to counter internal economic and social inequalities within the Union.

How can we strengthen the role of GIs in building European food sovereignty based on territorial identities, biodiversity and productive autonomy?

Geographical Indications today represent one of the most advanced models of “food democratization,” understood as “the set of practices and institutions that return decision-making power to local actors and citizens regarding the production, distribution and consumption of food,” since they connect governance among supply-chain actors, territorial identity and sustainability.

Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 reinforces this dimension, shaping producer groups as true democratic institutions: entities founded on rules of participation, representativeness and transparency, acting on behalf of all producers, preventing the concentration of power and ensuring a fair distribution of value along the supply chain.

Producer groups thus emerge not only as guarantors and promoters of quality, but also as key players in democratic processes, capable of establishing structured relationships with territorial entities –municipalities, regions and other public or private stakeholders – in the management of local resources, territorial planning and rural development policies.

From this perspective, GIs take on the role of micro-territorial sovereignties: real laboratories where communities exercise direct decision-making power, oriented towards productive diversification and quality. Thanks to this participatory structure, GIs contribute to building an agri-food system based on society’s needs, able to respond to citizens’ real demands and to integrate economic, social and environmental dimensions into a shared development model. GIs are not limited to food production, but involve all dimensions of the food system – from consumer education to product distribution, up to territorial promotion – following a participatory model built alongside local communities. Food sovereignty thus becomes a concrete practice, involving communities, institutions and citizens in creating a more just and participatory agri-food system.

The lines of intervention needed to strengthen the role of GIs as strategic elements of a European model of food sovereignty should include:

1. European harmonisation and coordination

• Spread the GI governance model evenly across Member States lacking a formal public administration structure dedicated to the sector, starting with the recognition of producer groups.

• Promote coordinated political action encouraging cross-border collaborations between GIs for the sharing of common quality standards, supporting the harmonised development of producer groups within the EU.

2. Democratic strengthening of producer groups

• In the respect of national specificities, promote uniform criteria for a democratic management of groups at Union level.

• Encourage, in all Member States, the recognition of producer groups as the only entities authorised to perform functions related to their respective GIs, emphasising their role as democratic administrators of a common good involving the entire supply chain.

3. Producer groups as “hubs” of territorial relations

• Promote collaboration protocols between producer groups, territorial entities and local stakeholders for the joint management of common goods, logistical infrastructures, and tourism or educational promotional activities.

• Formally recognise the representation of producer groups in territorial planning forums, ensuring their contribution to defining local agricultural policies, rural development plans and territorial valorisation strategies.

Scenario description

In the new scenario of resurgent protectionism and tariff conflicts among economic blocs, GI agri-food supply chains face mounting pressures. Customs barriers and regulatory uncertainty jeopardize exports, competitiveness and production continuity. Yet GIs can turn into active players of economic diplomacy, able to resist and negotiate even in contexts of commercial crisis.

What strategies can GIs adopt to face global tariff tensions while preserving the economic and symbolic value of their supply chains?

The shifting global balance and the return of protectionist policies highlight the crisis of multilateralism and the progressive weakening of the World Trade Organization. These phenomena stand in clear contrast with the founding principles of EU legislation on Geographical Indications, which has built an economic and cultural system rooted in territories and capable of generating shared value without resorting to commercial closure.

This model has been supported by international protection instruments, both through direct registration procedures and through bilateral and multilateral agreements – such as the Geneva Act – which have strengthened the presence of GIs on global markets and increased the resilience of supply chains.

However, the current global scenario and the use of tariffs as a negotiating tool expose GIs to tensions that threaten their competitiveness and market access, exacerbated by the limited awareness of their cultural and territorial value. In addition, the lack of uniform recognition and the regulatory fragmentation at international level encourage the proliferation of counterfeiting, amplified by the expansion of digital markets and by difficulties in applying effective protection tools.

In this context, GIs must enhance their distinctive character, positioning themselves as a model of economic resilience, territorial competitiveness and food security, replicable in any context, even in the most complex markets. An increasing number of countries recognise the advantages of this system: currently 167 States recognise GIs as intellectual property rights, and 111 have a dedicated regulatory framework. GIs thus emerge as tools of commercial transparency, consumer protection and enhancement of local economies – and not, as sometimes wrongly believed, as customs barriers.

To address global tariff tensions while preserving the economic and symbolic value of GI supply chains, several concrete actions can be identified:

1. Revision of trade policies

• Integrate the mutual recognition of GIs as an essential element in negotiating and concluding EU trade agreements.

• Promote the concept of a “tariff moratorium” or “zero duty” for the international trade of GIs, as recognition of the cultural and anti-speculative principles associated with them.

2. Protection and multilateralism

• Support the creation of an effective and transparent multilateral system for GI protection, enhancing the implementation of the 1958 Lisbon Agreement, revised with the 2015 Geneva Act, as a key instrument for multi-level protection.

• Allocate European public resources to developing a GI protection strategy on global markets, with special attention to digital platforms, international marketplaces and the management of domain names corresponding to GI denominations.

3. International cooperation

• Promote GIs as global tools for sustainable agricultural and rural development, capable of combining economic growth, social cohesion and environmental protection, recognising their value as collective heritage at both local and international levels.

• Support international cooperation programmes aimed at disseminating the GI model, particularly in developing countries, strengthening the EU’s role as a reference actor in the sharing of experiences and best practices.

Scenario description

A large part of the agricultural workforce in GIs is now made up of migrants, who are often invisible but essential. If well managed, GIs can become tools for inclusion, training and economic participation, activating virtuous models of rural citizenship and social cohesion.

Guiding question

How can we measure and enhance the overall contribution of GIs? How can we transform the presence of migrants in GI supply chains into a resource for the economic, cultural and social regeneration of local areas?

Social sustainability has become a key issue for both citizens and legislators. Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 highlights its importance in the transition toward a socially responsible system. Among the sustainable practices that groups can adopt, improving working conditions can have positive effects in countering rural depopulation and supports the goal of ensuring the competitiveness of supply chains on the market.

Geographical Indications are strategic tools not only for enhancing products but also for promoting social inclusion and economic opportunities in rural areas. The Italian experience illustrates this transformation: where businesses, Consortia, and local administrations have invested in professional training and stable employment, foreign workers have become an integral part of the rural community. These models demonstrate that product quality depends on the quality of labour, and vice versa. Sustainability certifications adopted in some territories show that a supply chain that protects workers generates reputation, international competitiveness, and increased local added value. In this perspective, the study “The Potential of Geographical Indications for advancing the Realisation of Farmers’ Rights” highlights how GIs can serve as a concrete tool to guarantee farmers’ rights. The experience of GIs shows that migration can become a resource rather than a vulnerability: when workers gain access to training, transparent contracts, and active participation in the economic and social life of communities, the territory produces not only high-quality goods but also social cohesion, human capital, and generational continuity.

For this reason, GI governance can and must assume a protective role: in managing supply chains, transferring skills, and fostering new forms of rural citizenship, with products that also serve as social guarantees.

To transform the presence of migrant workers in GI supply chains into a driver of rural development, intervention lines should focus on:

• Support the adoption of sustainable practices agreed upon by producer groups, ensuring consistent compliance across all actors in the supply chain.

• Map the specific needs of supply chains among businesses belonging to producer groups, in order to promote targeted pathways for the integration and advancement of migrant workers.

• Promote and finance training and professional development programmes for migrant workers, increasing their skills and opportunities to access qualified roles within GI supply chains, thus creating stable and not easily replaceable professional profiles.

• Identify and promote opportunities for qualified employment linked to activities complementary to GIs, encouraging the participation of multiple members of workers’ families. This strengthens their bond with the territory, facilitates stable settlement, and promotes social and cultural integration within the local community.

• Promote annual data collection for the regular analysis of the Geographical Indications contribution to sustainable development, including the role of the migrant workers.

• Provide financial and tax incentives to businesses that adopt socially sustainable practices and invest in training and integration of migrant workers within GI supply chains.

• Promote communication strategies that highlight the commitment of GI supply chains to social sustainability and the inclusion of migrant workers, strengthening their reputation and attracting consumers.

GIs generate value beyond simple turnover: they create employment, territorial attractiveness, reputation, sustainability and innovation. Today, an evolved vision of economic value is needed-one that considers their systemic and generative impact. Unlike high-margin, short-term business models, GIs create longterm value thanks to origin requirements, production rules and their deep rooting in territories. This is why competitive comparison should not be limited to annual performance but should consider multi-year economic sustainability, as demonstrated by indicators comparable to net present value (NPV) in the medium-to-long term. This is the moment to reformulate indicators, metrics and strategies that recognise their full potential.

How can we measure and enhance the overall contribution of GIs to the real economy, including social, environmental and cultural dimensions?

The ability to generate economic impact is a well-established fact that has contributed to the success of GIs. Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 outlines this strength among its objectives: by sharing added value along the entire supply chain, GIs ensure fair remuneration, allowing investment in quality, reputation and sustainability, and contributing to the achievement of rural development goals. It therefore emerges that, also thanks to collective organisation, they contribute to pursuing economic, social and environmental objectives. According to European and international studies, GIs produce a multiplier effect on territories: every euro spent in certified supply chains generates widespread value, increasing incomes, employment and business capacity. Compared to non-certified competitors, GI enterprises record higher average wages (+32%), greater employment of the workforce (+13%) and better export performance in terms of value and unit price. GIs thus represent collective goods with high territorial returns, able to transform quality into a lever for sustainable development and to strengthen the economic resilience of rural systems. However, measuring this value requires new tools: it is not enough to analyse annual margins or production value. A systemic, multi-year vision is needed, one that considers the contribution of GIs to the overall wealth of territories, including social, environmental and cultural dimensions. As recent legal doctrine observes, the use of economic indicators must avoid the risks of “managerial myopia”: quantification cannot replace the understanding of territorial complexity. Indicators should therefore be interpreted as dynamic tools, able to capture the plurality of values generated by GIs and to guide public policies towards long-term objectives.

From this perspective, the evolved economic value of GIs is no longer defined merely by total revenues, but by their ability to generate lasting well-being, territorial equity and relational capital.

1. Development of integrated indicators of territorial performance

• Create multidimensional indicators capable of measuring not only revenues and business margins, but also social impact (employment, training, inclusion), environmental impact (sustainable use of resources, biodiversity, emissions) and cultural impact (valorisation of local heritage and territorial identity). These indicators make it possible to quantify the added public-good value of GIs, considering economic, social, environmental and cultural effects.

• Apply multi-year and dynamic measurement methods to capture the evolution over time of the contribution of GIs to territorial development, avoiding “managerial myopia” based solely on annual results.

2. Monitoring and communication of the value generated

• Collect and analyse systematic data on GI supply chains, highlighting multiplier effects on income, employment, competitiveness and social cohesion in territories.

• Disseminate results through reports, certifications and communication campaigns to enhance the impact of GIs among institutions, consumers and markets, strengthening the reputation of products and the perception of their integrated value.

3. Support for public policies and incentive tools

• Integrate data on the value of GIs into rural development strategies, regional plans and EU agricultural policies, steering public interventions toward economic, social and environmental sustainability.

• Provide targeted incentives (financial, fiscal or training-related) for enterprises that demonstrate the ability to generate overall positive impact, promoting the spread of sustainable and innovative practices along the entire supply chain.

• Recognize Geographical Indications as priority products in the review of European public procurement legislation in 2026.

Scenario description

Cities are rediscovering local food as a lever for urban regeneration, social inclusion and sustainability. GIs can help redesign markets, public gardens, taste workshops and new proximity economies, bringing food culture back into the places of everyday life.

Guiding question

How can GIs become key players in new sustainable urban models, contributing to the ecological and social transition of cities?

The relationship between culture and sustainability in Geographical Indications emerges from Regulation (EU) 2024/1143, which recognises them as living cultural and gastronomic heritage, consecrating their value in promoting short distribution chains, with effects on social inclusion. In this context, Geographical Indications act as ambassadors of their territories and promoters of local food systems: they encourage short supply chains, guarantee traceability and offer certified products with cultural identity. Their presence in local markets, schools, cultural centres and teaching kitchens can transform these places into social infrastructures where food education, responsible consumption and local economic development are strengthened.

Producer groups – in Italy, the Consortia for protection – constitute the operational link, as they guarantee quality standards, coordinate promotional initiatives and training programmes, and interact with administrations, schools, businesses and communities. This participatory capacity facilitates the shared design of spaces, educational paths and tourism infrastructures connecting territorial production with urban life, enhancing landscape and culture. Scientific evidence and practical experience show that integrating GIs into urban food policies – through planning, educational programmes and public-private partnerships –strengthens food resilience, biodiversity and social cohesion. Therefore GIs are not only origin labels, but governance platforms that activate collaboration among producers, citizens and institutions, guiding local choices towards sustainable food models.

In summary, GIs and producer groups have both political and operational significance: they are strategic actors of the urban transition, capable of combining public objectives and community interests, and of transforming agri-food culture into a social infrastructure that improves the quality of urban life. For these reasons, they are ideal resources to promote urban food systems that are sustainable, inclusive and rooted in territories.

The lines of intervention to make GIs key players in urban regeneration and in the ecological and social transition must operate on multiple levels, combining governance, economy and public-space design.

1. Integration of GIs into urban and climate planning

• Integrate explicit objectives related to GIs into major urban policy instruments (food plans, biodiversity action plans, climate plans), so that the valorisation of certified productions becomes a guiding criterion for planning and for protecting peri-urban land.

• Recognise in urban plans the green corridors and productive periurban areas connected to GIs, introducing safeguards against soil fragmentation and the loss of ecological connectivity.

2. Multilevel governance and urban–rural partnership

• Establish permanent governance tables in which producer groups, local administrations and civil-society actors define integrated strategies for urban regeneration and ecological transition.

• Promote public–private agreements and supply-chain pacts between producer groups and local administrations for the shared management of public services, markets and training programmes.

3. Facilitated access to urban markets and promotion of proximity economies

• Simplify administrative procedures for direct sales and for the presence of GI products in local markets, urban events and temporary initiatives (pop-ups), while ensuring traceability and quality requirements.

• Encourage the creation of urban proximity economic circuits that promote the distribution of GI products and strengthen the direct relationship between producers and urban communities.

• Promote the creation of local trails connecting markets, restaurants and cultural sites.

The new generations – young people up to 25 years old – seek meaning, value coherence and identity in food. GIs can speak the language of young people, but they must renew narratives, educational tools and forms of engagement in order to become a cultural and political reference point in how young people inhabit the world.

A strategy is also needed to encourage young generations to approach the professions linked to GIs – not only in the agricultural sector, but also in processing, communication and product protection – enhancing traditional skills as levers for the jobs of the future.

How can we build a new cultural pact between GIs and young people, combining conscious consumption, sustainability and participation?

The EU legislator’s focus on sustainability also responds to the demands of society: more sustainable products attract the new generations, who are sensitive to environmental and social issues, and they encourage supply chains that guarantee transparency and traceability. A reliable information system, as provided for by Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 –especially for processed products – strengthens consumer trust and responds to these expectations thanks to clear and coherent labelling. The regulation also recognises the importance of generational renewal, assigning producer groups an active role in fostering the entry of young farmers, leveraging economic attractiveness as well as environmental and social dimensions.

Geographical indications can become a cultural and political language through which the new generations rebuild their food citizenship: not just quality labels, but frameworks of meaning that connect identity, sustainability and opportunities.

GIs can make agricultural work more attractive by combining employment, sustainable innovation and territorial rootedness. They are also closely associated with landscapes and cultural heritage valued by young people: territorial analyses show a clear overlap between GI productions and socio-ecological values, offering a narrative in harmony with youth sensibilities. To engage Generation Z, however, it is necessary to renew narratives, educational tools and engagement methods. Research shows that certification accompanied by clear information and educational, territorial communication increases the propensity to purchase. Two priorities follow: education on GIs and active employment policies for young people within certified supply chains. Despite their potential, today only 12% of EU farmers are under 40, indicating a large margin for action to make the sector more attractive and sustainable for younger generations.

The actions proposed here aim to build a new cultural pact between GIs and youth, combining conscious consumption, sustainability and participation.

1. Education and awareness on GIs

• Integrate into school, vocational and university curricula modules dedicated to GIs, territorial quality, sustainability and food safety, using shared teaching materials and experiential approaches.

• Promote common guidelines for educational communication –such as educational labels, QR codes and multimedia content – that explain the origin, sustainable impacts and cultural value of the products.

2. Alliances for the conscious promotion of GIs

• Activate partnerships between producer groups and restaurant networks with young customers, to include PDO and PGI products on menus while transparently communicating origin, sustainability and specific qualities.

• Involve influencers and digital communities in co-creating content that spreads food culture and raises awareness of GI values, highlighting their contribution to sustainability and territorial identity.

3. Youth employment in supply chains

• Increase the attractiveness of the sector through incentives, income-support measures and effective training programmes for young people, with the goal of reaching 30% young people active in agriculture, in line with the EU Strategy for generational renewal.

• Introduce, within producer groups, participatory mechanisms dedicated to young people to ensure representation, narrative renewal and active involvement in GI governance.

7. Artificial intelligence, digital life and GIs: new challenges for the identity and narrative of food

Scenario description

Artificial intelligence is changing the way we understand, choose and narrate food. GIs must inhabit this new digital ecosystem without losing authenticity and meaning, becoming active protagonists in the construction of augmented narratives, intelligent traceability and ethical promotion tools.

Guiding question

How can the encounter between GIs and artificial intelligence be guided to strengthen the transmission of knowledge and the cultural identity of food?

The advent of new technologies has prompted the European legislator to intervene in the protection of Geographical Indications on e-commerce platforms and domain names, extending ex officio protection and introducing an alert system. However, to ensure reliable information and promote the dissemination of knowledge, it is necessary to consider the potential and implications of artificial intelligence as a support tool not only for consumers, but also for producer groups and businesses. In this perspective, Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 calls on producer groups to take responsibility for disseminating knowledge related to technical-scientific progress and digitalisation, as required by Article 32. artificial intelligence can become a fundamental tool for managing the complexity of producer groups’ activities and the sector as a whole. The increase in functions provided for by the regulation, the rapid changes in markets and consumer behaviour, and the operational needs of the supply chain no longer represent insurmountable obstacles, but constitute an opportunity – particularly for smaller organisations with limited resources.

With modest investments, groups can develop AI-based models for data management, market analysis and monitoring of protection. For example, AI can be used for the collection and analysis of data required for drafting the sustainability report introduced by the regulation, simplifying the application of sustainable practices and improving communication on producers’ actions.

The potential of new technologies requires a strategic and integrated approach by producer groups, supported by institutions and businesses, enabling them to operate more efficiently, reduce gaps between small and large organisations and promote innovative and virtuous growth of the agri-food sector linked to quality productions.

The actions proposed to guide the encounter between GIs and artificial intelligence – valid on a European scale and adaptable to different territories – are:

1. Optimising the operational management of producer groups

• Promote the use of AI-based solutions to support producer group activities, improving operational efficiency.

• Support initiatives aimed at effective use of AI, including training programmes for operators, digital assistance tools and pilot projects.

2. Funding and incentives for AI adoption

• Create specific funding tools to support producer groups in adopting and implementing AI-based solutions along the entire supply chain, including for protection, enforcement and anticounterfeiting activities.

• Introduce reward criteria in public funding for producer groups and businesses, favouring projects that use AI tools to improve project efficiency.

• Promote the use of big data on production among producers, especially young ones.

3. Cooperation and skills development

• Encourage collaborative networks among producer groups, promoting the exchange of best practices and the shared adoption of AI-based solutions.

• Organise laboratories, mentoring sessions and workshops within producer groups to foster collective development of digital skills, increasing members’ ability to use AI in a coordinated and sustainable way.

Scenario description

Food is a universal language and a cultural heritage. GIs can be tools of soft power, cultural diplomacy and representation of European identity in the world, promoting cohesion and intercultural dialogue. But narrative and institutional strategies are needed to support this role in a coherent and recognisable way.

Guiding question

How can we strengthen the role of GIs as cultural ambassadors of Europe in international, educational and diplomatic contexts, also through sustainable food and wine tourism initiatives?

Geographical Indications are today an economic advantage for Europe and a resource of cultural identity. Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 recognises their role in protecting cultural diversity and intangible heritage. Related activities, such as food and wine tourism, expand the reach of GIs, transforming them into tools of territorial diplomacy that connect local economy, tourism and culture. GIs must be considered cultural ambassadors: they carry knowledge, practices and collective memories that transcend language barriers. When enhanced in public policies and international relations, they operate as levers of soft power, translating European identity into shared narratives and fostering social cohesion and sustainable development.

Turismo DOP is an integrated model that makes GIs drivers of attractiveness and cultural education. Experiences in production sites, training pathways and cultural initiatives highlight the link between product, landscape and intangible heritage, transforming the visit into an act of knowledge and citizenship. In this way, GIs assume an educational and civic function, spreading authenticity, sustainability and the diversity of European identity. Gastro-diplomacy promotes a country’s image through cuisine and symbolic products, building trust and dialogue between peoples and institutions. GIs, as deeply rooted expressions of territories, make this practice credible. In synergy with Turismo DOP, gastro-diplomacy becomes a tool for educating about cultural diversity, encouraging the understanding of territories through tourism and educational experiences that unite gastronomic heritage and sustainability.

To strengthen these roles, it is necessary to integrate GIs into European cultural and diplomatic strategies: promoting heritage, protecting food diversity and constructing a common narrative. Coordination between cultural, tourism, trade and cooperation policies is essential to avoid homogenisation and to make GIs platforms for encounters between memory and innovation, market and culture.

To consolidate the role of Geographical Indications as cultural ambassadors of Europe, three cross-cutting and adaptable lines of intervention for different territories of the Union are proposed:

1. Consolidating the cultural, educational and diplomatic dimension of GIs

• Integrate into regulatory frameworks and promotional policies elements that recognise the cultural value of GIs, including stories, knowledge, production practices and community heritage.

• Integrate GI products into European public diplomacy: events organised by foreign rep

• Presentations, cultural networks, exchange programmes and educational courses related to European cuisine and food heritage.Included GIs in the European strategy on sustainable tourism, which will be published in 2026.

2. Strengthening networks, narratives and access tools

• Promote cultural, digital and tourism platforms that narrate GIs through itineraries, multimedia archives, events and initiatives that encourage direct experiences in production companies.

• Support collaboration networks between territorial enterprises linked to food culture and transnational networks of producers, cultural institutions, tourism operators and diplomatic bodies aimed at designing joint campaigns, professional exchanges and training pathways dedicated to European gastro-diplomacy.

3. Ensuring plurality, participation and ethical protection

• Adopt inclusive governance models that involve local communities, producer groups and scientific institutions, ensuring representation, transparency and respect for territorial heritage.

• Promote plural narratives that reflect the cultural complexity of territories, highlighting the difference with commercial brands and enhancing diversity as a guarantee of credibility in international dialogue.

oriGIn

Siena - December 6, 2025

This Green Paper, drawn up jointly by the organisations oriGIn, oriGIn Europe, Origin Italia, Origen España, oriGIn France and Qualifica–oriGIn Portugal, with the scientific and methodological support of the Fondazione Qualivita, is submitted to the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural Development, Christophe Hansen, as a strategic contribution from the Geographical Indications system to the implementation phase of Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 and to the future of European GIs.

The document provides a shared reading of the main challenges facing all European GIs – from sustainability to digitalisation, from international protection, including online, to the promotion of tourism in the territories, through to the development of transnational free-trade rules and the strengthening of the role of Consortia and producer organisations – and puts forward a series of operational proposals to consolidate the European Geographical Indications model in the coming years.

Through this Green Paper, the representatives of the GI system call on the European Commission to:

1. Launch a structured follow-up process which, starting from Regulation (EU) 2024/1143, defines a genuine European Action Plan on Geographical Indications, with clear objectives, instruments, resources and timelines.

2. Strengthen coordination between quality, trade, digital, environmental, rural development and tourism policies, enhancing GIs as a cross-cutting lever for sustainable development in European rural areas.

3. Ensure the stable involvement of GI system organisations in decision-making processes and in European and international discussion fora, recognising their role as technical and institutional interlocutors for the protection of supply chains and consumers.

The Green Paper on the Future of Geographical Indications thus aims to provide the European Commission with a concrete and shared working platform, arising from dialogue among the key players in the Geographical Indications system, to support the new phase of European quality policies.

Charles Deparis

oriGIn Europe

Origin Italia

oriGIn France

Origen España

Teresa Pais Coelho

Qualifica–oriGIn PT

Cesare Mazzetti Fondazione Qualivita

1. Ailin, T., Sharizal, B. H., Jiaqi, Z., & Jianyu, C. (2024). Consumer responses and determinants in geographical indication agricultural product consumption. F1000Research. https://f1000research.com/articles/13-1410

2. Aveni, A. (2025). Tariffs turbulences in 2025: Intellectual property trade barriers, local trade protections vs. tariffs. Revista Processus de Estudos de Gestão, Jurídicos e Financeiros, 16(51), e511477. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16846683

3. Asioli, D., Canavari, M., & Vecchio, R. (2023). Can traditional food product communication convey safety to the younger generations? Foods, 12(2754). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12272554

4. Belletti, G., Marescotti, A., & Touzard, J.-M. (2017). Geographical indications, public goods, and sustainable development: The roles of actors’ strategies and public policies. World Development, 98, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.004

5. Belletti, G., Marescotti, A., Touzard, J.-M., & Thévenod-Mottet, E. (2021). The geographical indication pathway to sustainability: A framework to assess and monitor the contributions of geographical indications to sustainability through a participatory process. Sustainability, 13(14), 7535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147535

6. Berti F. (2025). In vino veritas. Il lavoro immigrato nelle produzioni vitivinicole della provincia di Siena. (in corso di pubblicazione

7. Bonanno, A. (2019). Geographical indication and global agri-food: Development opportunities and challenges. Routledge. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/103159

8. Bonetti, E., Bartoli, C., & Mattiacci, A. (2024). Applying blockchain to quality food products: A marketing perspective. British Food Journal, 126(5), 2004–2026. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2022-1085

9. Cabral, Ó., Lavrador, L., Orduna, P., & Moreira, R. (2024). From the kitchen to the embassy: A rapid review of gastronomic approaches in diplomacy. Place Branding & Public Diplomacy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-024-00363-4

10. Ciardella, G., & Nobile, A. (2024). L’intelligenza artificiale come strumento innovativo nella lotta all’Italian Sounding. Consortium n° 22 (01/24).

11. Colamartino, C., Manta, F., & Toma, P. (2024). NFTs for certified products: A heritage to protect on the “table” of the metaverse. Applied Economics, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2024.2364095

12. Commissione Europea. (2021, 30 giugno). Una visione a lungo termine per le zone rurali dell’UE: Verso zone rurali più forti, connesse, resilienti e prospere entro il 2040 [Comunicazione della Commissione al Parlamento Europeo, al Consiglio, al Comitato Economico e Sociale Europeo e al Comitato delle Regioni].

13. Crescenzi, R., De Filippis, F., Giua, M., & Vaquero-Piñeiro, C. (2021). Indicazioni geografiche e sviluppo locale: La forza dell’inserimento territoriale. Studi Regionali, 56(3), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1946499

14. Curzi, D., & Huysmans, M. (2022). The impact of protecting EU geographical indications in trade agreements. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 104(1), 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12226

15. Czarnecka, A., & Gębski, J. (2023). Importance of regional and traditional EU quality schemes in young consumer food purchasing decisions. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sectio H – Oeconomia, 57(2), 55–68. https:// bazawiedzy.umcs.pl/info/article/UMCS801374befc494e3cb9432ec2890af512

16. D’Onofrio, R., & Di Bella, E. (2022). Downscaling food system for the “public city” regeneration: An experience of social agriculture in Trieste. Sustainability, 14(5), 2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052769

17. Del Giudice, T., & Cavallo, C. (2023). The impact of Nutri-Score on consumers’ preferences for geographical indications. Quality – Access to Success, 24(198), 45–53. https://www.iris.unina.it/handle/11588/998623

18. Di Lauro, M. (2025). La sostenibilità nelle DOP e IGP: note critiche sul “governo” degli indicatori. In Scritti in onore di A. Jannarelli (in corso di pubblicazione). Torino: Giappichelli.

19. Engelhardt, T. (2015). Geographical Indications Under Recent EU Trade Agreements. IIC – International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 46, 781–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-015-0391-3

20. European Commission. (2020). Geographical indications to build up resilient rural economies: A case study from Ghana. Publications Office of the European Union.

21. European Commission, DG Agriculture and Rural Development. (2013). Study on assessing the added value of PDO/PGI products.

22. FAO 2023 - Estimating global and country-level employment in agrifood systems - https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/ api/core/bitstreams/08f5f6df-2ef2-45a2-85aa-b29c2ce01422/content

23. Falsini, S., Biagini, L., & Belletti, G. (2024). Mapping young farmers’ choice to pursue geographical indication in a rural context: Application of fuzzy cognitive map. Agricultural and Food Economics, 12(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-024-00340-8

24. FitzGerald, J. (2023). Exploring the EU Geographical Indications (GI) system as a policy tool for strengthening Ireland’s food heritage (MSc thesis, Wageningen University & Research). Wageningen University & Research. https://edepot.wur.nl/587055

25. Flinzberger, L. (2023). Geographical indications as tools for sustainable landscape management (Doctoral dissertation, University of Göttingen). Göttingen University Press. https://ediss.uni-goettingen.de/handle/11858/15005

26. Forman, J. M. (2024). Gastrodiplomacy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Food Studies. Oxford University Press. https:// doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780197762530.001.0001/acrefore-9780197762530-e-18

27. Gangjee, Dev S. (2012). Geographical Indications and Cultural Heritage. WIPO Journal, 4, 92-102. https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2187768

28. Huysmans, M. (2022). Exporting protection: EU trade agreements, geographical indications, and gastronationalism. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 979–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1844272

29. Josling, T. (2006). The war on terroir: Geographical indications as a transatlantic trade conflict. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 57(3), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2006.00075.x

30. Joint Research Centre (JRC). (2021). Causal estimation of the effect of geographical indications on territorial development in Portugal (JRC124769). Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/ JRC124769

31. Joint Research Centre (JRC). (2024). Geographical indications and vineyards: An EU-wide analysis of economic and environmental performance (JRC135467). Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ repository/handle/JRC135467

32. Kae, H., Yim, J., & Kim, T. (2019). Organic and geographical indication certifications’ contributions to employment and education. Journal of Agriculture and Food Industrial Organization, 17(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1515/jafio-2019-0042

33. Kamenidou, I., & Mamalis, S. (2024). Exploring young consumers’ understanding of local food. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 1464548. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1464548

34. Kizos, T., & Vakoufaris, H. (2020). Do geographical indications preserve farming in rural areas? Evidence from a natural experiment in Japan. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.004

35. Lee, S. T., & Kim, H. S. (2020). Food fight: Gastrodiplomacy and nation branding in Singapore’s UNESCO bid to recognize Hawker culture. Place Branding & Public Diplomacy, 17(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-020-00166-3

36. Liu, Y., Wang, J., & Zhang, J. (2023). Consumption behavior intention of geographical indication products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 51(8), e13888. https://doi.org/10.2224/ sbp.13888

37. Liu, Z., Yu, X., Liu, N., Liu, C., Jiang, A., & Chen, L. (2025). Integrating AI with detection methods, IoT, and blockchain to achieve food authenticity and traceability from farm-to-table. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 158, 104925. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.104925

38. Magdas, D. A., Hategan, A. R., David, M., & Berghian-Grosan, C. (2025). The journey of artificial intelligence in food authentication: From label attribute to fraud detection. Foods, 14, 1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101808

39. Magnini, L. (2023). Incorporating cultural heritage in the proposal for a regulation on geographical indications protection for craft and industrial products. Stockholm Intellectual Property Law Review, 6(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.53292/ fb09c833.373d6dde

40. Marie-Vivien, D., & Biénabe, E. (2020). Strengthening sustainable food systems through geographical indications: Evidence from 9 worldwide case studies. Journal of Sustainability Research, 2(3), 0031. https://doi.org/10.20900/jsr20200031

41. Massacci, A., Casprini, E., & Zanni, L. (2025). Consumo sostenibile di vino: un’analisi tra le Gen Z italiane e americane. Consortium, 28(3/2025). ISSN 2611-8440 (stampa), ISSN 2611-7630 (online).

42. May, S., Sidali, K. L., Spiller, A., & Tschofen, B. (Eds.). (2017). Taste Power | Tradition: Geographical indications as cultural property. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/37145

43. Menapace, L., & Moschini, G. (2024). The economics of geographical indications: An update. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 16(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-101623-092812

44. Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali (2024) - XIV Rapporto “Gli stranieri nel mercato del lavoro” - https:// integrazionemigranti.gov.it/it-it/Dettaglio-approfondimento/id/59/XIV-Rapporto-Gli-stranieri-nel-mercato-del-lavoro

45. Mohamed Jaffar, A. (2024). Geographical indications of products at the global level and challenges of India. Quest Journals: Journal of Research in Business and Management, 12(4), 134–142. ISSN 2347-3002.

46. Motoki, K., Low, J., & Velasco, C. (2025). Generative AI framework for sensory and consumer research. Food Quality and Preference, 133, 105600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2025.105600

47. Müller, C., Gómez, M., & Fréguin-Gresh, S. (2024). Do territories with geographical indications trade better? Review of International Economics, 32(4), 1002–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-024-00269-3

48. Mutyasira, V. (2020). Geographical indication to build up resilient rural economies: A case study from Ghana. Sustainability, 12(22), 9543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229543

49. Nirosha, R., & Mansingh, J. P. (2025). Mapping the sustainability of geographical indication products: A systematic literature review. Discover Sustainability, 6, 549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-01332-4

50. Oxfam, 2024 - https://oxfam.se/en/news/miljontals-migrantarbetare-inom-jordbrukssektorn-utnyttjas-i-europa/

51. Özkan, E., & Uzun, S. (2023). Rural revitalization through territorial distinctiveness: The use of geographical indications in Turkey. Land Use Policy, 131, 106689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2023.106689

52. Poetschki, K., Peerlings, J., & Dries, L. (2021). The impact of geographical indications on farm incomes in the EU olives and

wine sector. British Food Journal, 123(13), 579–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2020-1119

53. Pungetti, G., & Siciliano, G. (2022). Labor exploitation in the Italian agricultural sector: The case of vulnerable migrants in Tuscany. Sustainability, 14(4), 2345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042345

54. Qualivita. (2025). Trump, dazi e indicazioni geografiche: La strategia USA e la risposta europea. Qualivita News. Recuperato da https://www.qualivita.it/news/trump-dazi-e-indicazioni-geografiche-la-strategia-usa-e-la-risposta-europea/

55. Quiñones-Ruiz, X. F., Penker, M., Belletti, G., Marescotti, A., & Brocca, S. (2022). EU-wide mapping of protected designations of origin (PDOs) and their social-ecological values. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 42, 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s13593-022-00778-4

56. Raimondi, V., Falco, C., Curzi, D., & Olper, A. (2020). Trade effects of geographical indication policy: The EU case. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 71(2), 330–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12349

57. Rivera, M., Cuéllar-Padilla, M., & Guzmán, G. I. (2024). Territory in urban food policies: The case of Spain. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 8, 1359515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1359515

58. Rwigema, P. C. (2024). Sustainable development through effective leadership and cultural democracy in East Africa (EAC). Reviewed International Journal of Political Science & Public Administration, 5(1), 15–34. https://www.reviewedjournals.com/ index.php/rijpspa/article/view/175

59. Salazar, D. S. (2024). The multiple edges of gastrodiplomacy: The paradoxes of the Basque case. Place Branding & Public Diplomacy, 20(2), 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-023-00317-2

60. Schimmenti, E., Migliore, G., & Borsellino, V. (2021). The contribution of geographical certification programs to farm income and rural economies: Evidence from Pecorino Siciliano PDO. Sustainability, 13(8), 4421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084421

61. Sood, E., & Sharma, Y. (2024). Geographical indicators as tools of economic development. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 70(4), 774–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/00195561241248137

62. Stranieri, S., Orsi, L., De Noni, I., & Olper, A. (2023). Geographical indications and innovation: Evidence from EU regions. Food Policy, 116, 102443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102443

63. Stranieri, S., Orsi, L., Zilia, F., De Noni, I., & Olper, A. (2024). Terroir takes on technology: Geographical indications, agrifood innovation, and regional competitiveness in Europe. Journal of Rural Studies, 110, 103368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jrurstud.2024.103368

64. Torelli, F., & Marescotti, A. (2021). Why geographical indications can support sustainable development in European agri-food landscapes. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2, 752377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.752377

65. Vandecandelaere, E., Arfini, F., Belletti, G., & Marescotti, A. (2010). Linking people, places and products: A guide for promoting quality linked to geographical origin and sustainable geographical indications (2nd ed.). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/4/i1760e/i1760e.pdf

66. Vandecandelaere, E., Teyssier, C., Barjolle, D., Fournier, S., Beucherie, O., & Jeanneaux, P. (2020). Strengthening sustainable food systems through geographical indications: Evidence from 9 worldwide case studies. Journal of Sustainability Research, 2(3), 1279. https://sustainability.hapres.com/htmls/JSR_1279_Detail.html

67. Varavallo, G., Caragnano, G., Bertone, F., Vernetti-Prot, L., & Terzo, O. (2022). Traceability platform based on green blockchain: An application case study in dairy supply chain. Sustainability, 14(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063321

68. Vieira, J. (2017). Écocitoyenneté et démocratie environnementale [Thèse de doctorat, Université de Bordeaux]. Université de Bordeaux.

69. Wang, Y., Jiang, Y., & Xu, H. (2024). AI thenticity: Exploring the effect of perceived authenticity of AI generated visual content on tourist patronage intentions. Journal of Tourism and Technology. https://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/10986/

70. Wilson, R. (2011). Cocina peruana para el mundo: Gastrodiplomacy, the culinary nation brand, and the context of national cuisine in Peru. Exchange: The Journal of Public Diplomacy, 2(1), 13–20. https://surface.syr.edu/exchange/vol2/iss1/2

71. Xia, T., Shen, X., & Li, L. (2024). Is AI Food a Gimmick or the Future Direction of Food Production?–Predicting Consumers’ Willingness to Buy AI Food Based on Cognitive Trust and Affective Trust. Foods, 13(18), 2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/ foods13182983

72. Yan, X., & Zhang, Q. (2023). Migrant labour flows and interconnected agrarian transformations in Southern China. Journal of Rural Studies, 103, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.02.007

73. Vaquero-Pineiro, C. (2023). Indicazioni Geografiche tra sviluppo locale e internazionalizzazione. In Giornate della Ricerca del Dipartimento di Economia di Roma Tre (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/10.13134/979-12-5977-286-2/15

74. Zappalaglio, A. (2023). Understanding the functioning of EU geographical indications (Policy brief no. 116). South Centre. https://www.southcentre.int/policy-brief-116-7-march-2023/

75. Zappalaglio, A. (2025). A short history of the relationship between EU agricultural GIs and the Common Agricultural Policy: From the beginning to Regulation 2024/1143. Yearbook of European Law, in press. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/ eprint/225660/

76. Zelený, J., Ulrichová, A., Fišer, V., Husák, J., & Svobodová, D. (2024). Gastronomic consumers’ attitudes toward AI-generated food images: Exploring different perceptions based on generational segmentation. In J. L. Reis, J. Zelený, B. Gavurová, & J. P. M. dos Santos (Eds.), Marketing and smart technologies. ICMarkTech 2023. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies (Vol. 386). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-1552-7_8

1. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – Strategy for generational renewal in agriculture, 21 October 2025, COM(2025) 872 final.

2. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2025/27, of 30 October 2024, supplementing Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 of the European Parliament and of the Council with rules on the registration and protection of geographical indications, Traditional Specialities Guaranteed and optional quality indications, and repealing Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 664/2014.

3. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/26, of 30 October 2024, laying down implementing provisions of Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards registrations, amendments, cancellations, the application of protection, labelling and the communication of geographical indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed, amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/34 as regards geographical indications in the wine sector, and repealing Implementing Regulations (EU) No 668/2014 and (EU) 2021/1236.

4. Regulation (EU) 2024/1143 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 11 April 2024, on the geographical indications of wines, spirit drinks and agricultural products, as well as on Traditional Specialities Guaranteed and optional quality indications for agricultural products, amending Regulations (EU) No 1308/2013, (EU) 2019/787 and (EU) 2019/1753 and repealing Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012.

5. Regulation (EU) 2023/2411 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 18 October 2023, on the protection of geographical indications for craft and industrial products, and amending Regulations (EU) 2017/1001 and (EU) 2019/1753.

6. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system, 20 May 2020, COM(2020) 381 final.

7. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – The European Green Deal, 11 December 2019, COM(2019) 640 final.

8. Regulation (EU) 2019/1753 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 23 October 2019, on the Union’s action following its accession to the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications.

9. Regulation (EU) 2019/787 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 17 April 2019, on the definition, description, presentation and labelling of spirit drinks, on the use of spirit drinks’ names in the presentation and labelling of other foodstuffs, on the protection of geographical indications for spirit drinks and on the use of ethyl alcohol and agricultural distillates in alcoholic beverages, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 110/2008.

10. Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications, adopted in Geneva on 20 May 2015.

11. Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 17 December 2013, establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007.

12. Green Paper of 15 October 2008 on the quality of agricultural products [COM(2008) 641 def.].

13. International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), adopted in Rome on 3 November 2001.

14. Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), Annex 1C to the Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization, signed in Marrakesh on 15 April 1994, ratified by Law No. 747 of 29 December 1994.

15. Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration, adopted in Lisbon on 31 October 1958, revised in Stockholm on 14 July 1967 and amended on 28 September 1979.

www.qualivita.it - www.qualigeo.eu