Olive Kids is an Australian Foundation dedicated to the support of children in Palestine. They provide finiancial aid, healthcare, education, and other support. 92% of their revenue goes towards grants and donations made for use outside Australia (ACNC, 2025).

Scan the QR code to visit their website and donate.

PULP is published on the sovereign land of the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation. We pay our respects to Elders past and present, as well as Indigenous members of our creative community. We respect the knowledge and customs that traditional Elders andAboriginal people have passed down from generation to generation. We acknowledge the historical and continued violence and dispossession against First Nations peoples. Australia’s many institutions, including the University itself, are founded on this very same violence and dispossession. As editors, we will always stand in solidarity with First Nations efforts towards decolonisation and that solidarity will be reflected in the substance and practice of this magazine.

Sovereignty was never ceded. Always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Senior Editor

Sasha Blackman

Editors

Rosanna Chim

Portia Love

Jayden Nguyen

Jess Watson

Sophie Wishart

Ege Yurdakul

Design

Portia Love

Sophie Wishart

Ege Yurdakul

The views in this publication are not necessarily the views of USU. The information contained within this edition of PULP was correct at the time of printing. This publication is brought to you by the University of Sydney Union.

Issue 24, 2025

Nothing I say can top the Editors’ Note on the following page. So I’ll take a turn on the bottom.

Creating this issue, the juice of PULP Nation’s creativity trickled down our skin and we slurped up every last drop.

We dissected the flesh of the city, reflected upon beloved places, unravelled our skin from our bones, and revealed our throbbing hearts.

Summer is coming; Issue 24 is out. Pick it up, wipe your greasy fingers all over it, and devour it cover to cover.

Love, Sasha

“Fuck the paperwork.”

I’m waiting in the foyer of the Holme building, the stand at Taste, Fisher Library. Hoping to catch your eye across the room. Longing to be possessed by you. To be cradled in your arms, devoured, or savoured for later. No, fuck that.

Open me now.

With just one flick of your thumb, I release for you. Turning my pages, a finger running down my spine. The way your eyes trail across my body (of text). Something deep inside me shifts when you enter my pages.

Grip me firm but gently, enough for your palms to leave my covers damp. I’m waiting for your fingertips to slip across my 95gsm pages as the seasons become warmer.

Stare at my contents. I’m still waiting for you across campus, in these evenings which are lasting longer. No need to rush, let your eyes linger. We can stay on campus together, reading all night, if you like. Pass me around, bring me home and spread me wide on your table.

“The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.”

The PULP editors

THANK YOU

ELOISE, ESTHER, CASPAR, KATE, BIP, LACHLAN & MAYA.

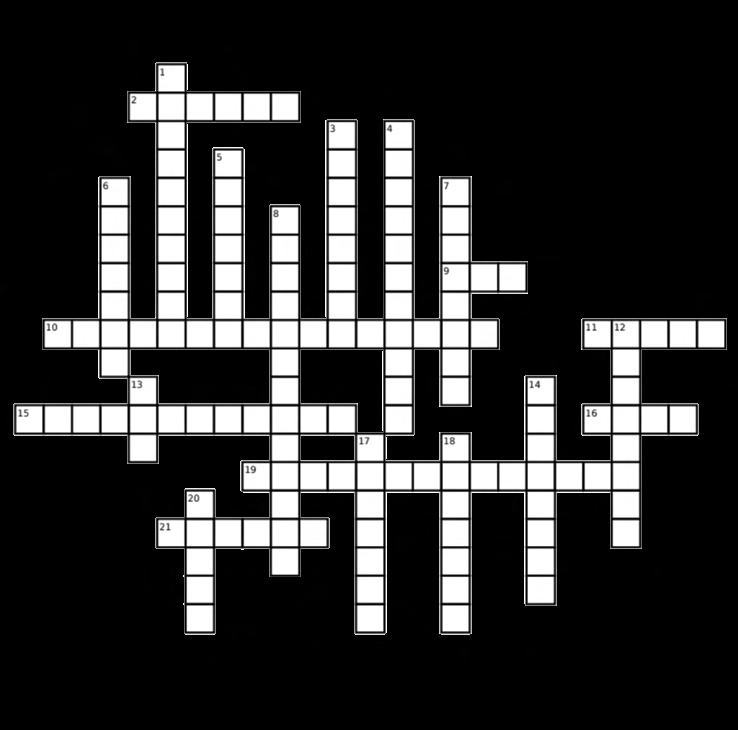

1. An economic system guided by profit controlling the American political system (10)

3. Borough that Gossip Girl lives in (8)

4. Societal condition which could be characterised by obsessive Labubu purchasing (11)

5. You drink this type of beer at the Courty and probably have a snake tattoo (7)

6. Eye gear (7)

7. Where to find someone to hook up with and never speak to again (lesbian edition) (8)

8. Someone excessively concerned about their health (13)

12. A Northern arm of the Mediterranean sea, near the Balkans (8)

13. Mostly disappointing and sometimes creepy (3)

14. Bones (8)

17. Country of the Chu Chi tunnels (7)

18. An artistic montage usually involving scissors and glue (7)

20. Empty validation for performative exercising (5)

2. People close to you both loved and hated (6)

9. Used to colour clothes (3)

10. Capitalist propaganda luring migrants to the USA (3,8,5)

11. Known as The King of Fruits, aam, aamra or mangai (5)

15. Foucault would not endorse but is always discussing (12)

16. By-product of the body or a term used to describe beer (4)

19. Hates change and might be racist (14)

21. Sandwich brand that sells awesome cookies (6)

Running Simulator 2025

Jack Davis

Love Letters to the Adriatic

Clara Medanic

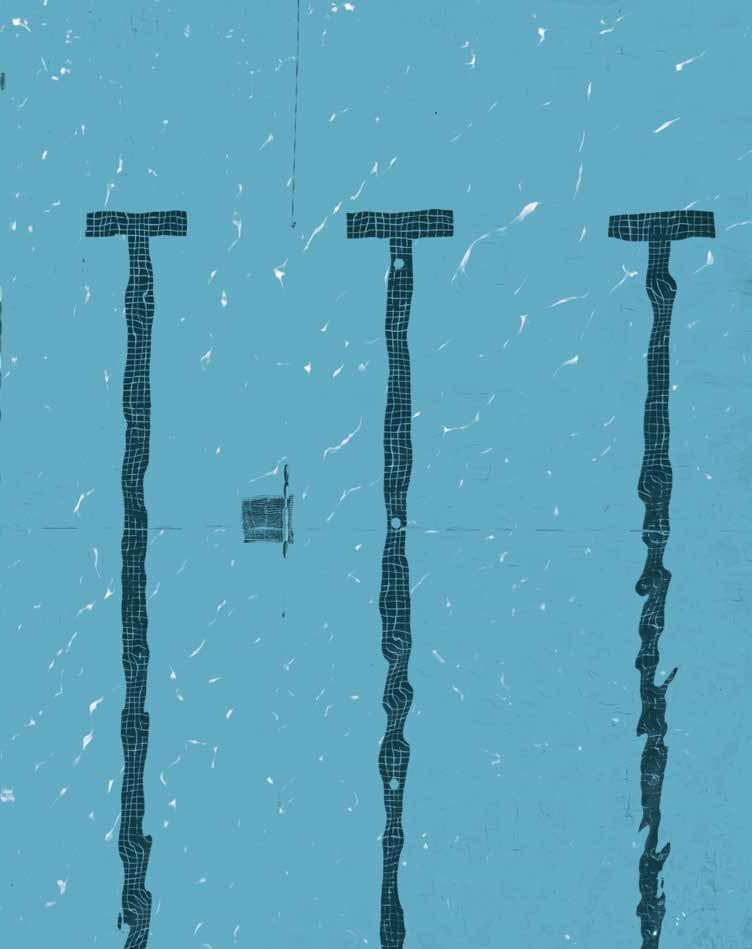

Overthinking: Swimming Dilemmas

Urvi Agrawal

Comfort, Exclusion, and the Mall

Marc Paniza

Memory: A Practical Guide

Amelia Elliott

Theory, Self-Inserted: Practical Investigations of Gender and Sexuality

Ella Kratzer

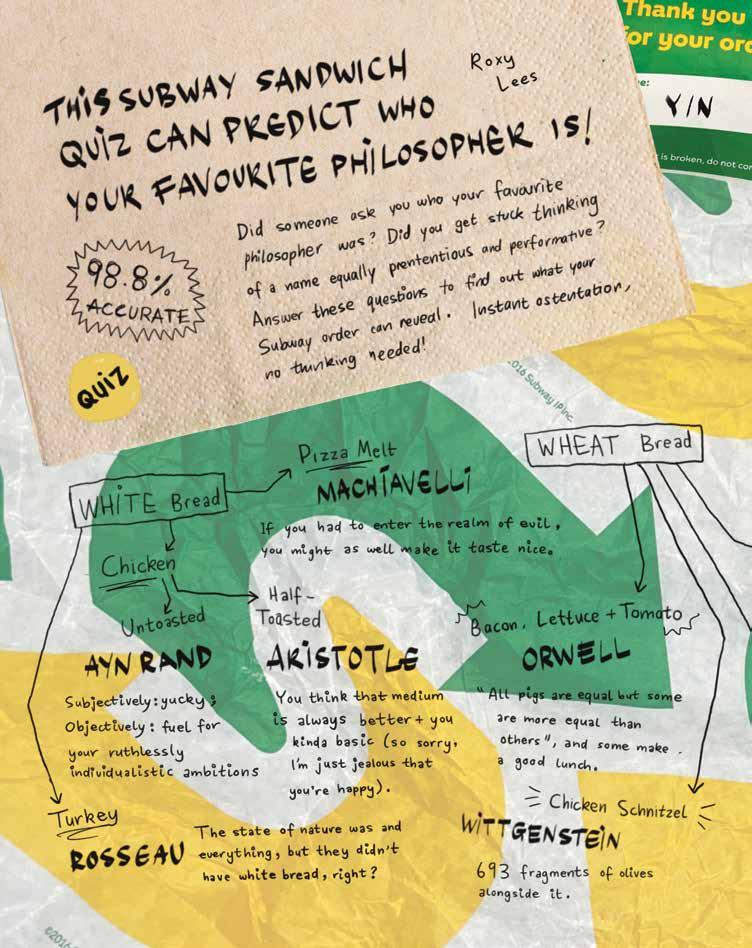

This Quiz Can Predict Who Your Favourite Philosopher Is!

Roxy Lees

Cao lầu

Jeannette Monteiro

The Yabbies

Soraya Moore

Embodied Dissent

Sage Belgum

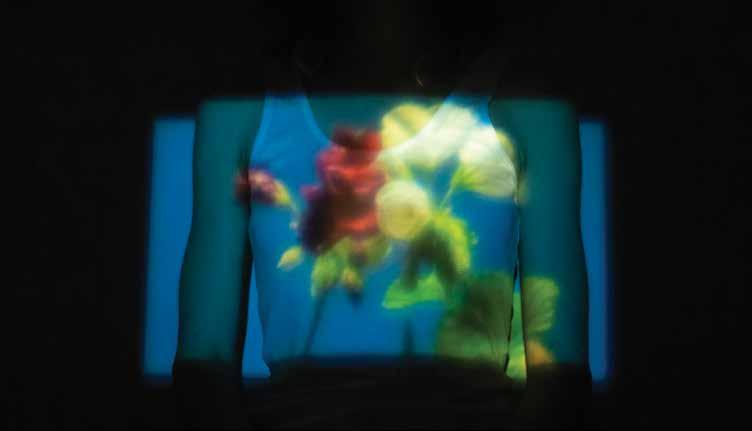

Unravel Me

Sophie Wishart

Cooked

Matilda Azmi

Pișatu Pișătorilor

Cosmin Luca

Scoody Doo and Daphne's Red Ascot

Nathan Phillis

Man and a Woman

Allegra Pezzullo

i bear it all yet still they do not see

Eloise Tilbury

Vauge Memories of a Distant Home

Samadhi Kumarage

Jack Davis

I was strolling peacefully through Victoria Park on a recent afternoon after class, savouring the musty burnt-toast smell that hangs over the junction of Parramatta Road and City Road as the sun finally emerged from its August sabbatical. The ibises were sunbathing. The LimeBike helmets floating in the brackish water of Lake Northam could have been some kind of exotic lotus, newly introduced to Australian shores. I was at peace, briefly…

This reverie was truncated by the sweaty interruption of a shirtless body flying past me, clad in moisture-wicking short shorts and hot pink running shoes.

A flash of electric blue Oakley sunglasses screamed past my peripheral vision. I felt a spray of electrolyte-enriched, high-performance sweat coat the side of my face. Before I could register any more salient information about this athletic specimen, he was gone, running on a plane of pure velocity that I may never access.

I’m certain you know someone who runs. I’m also cognisant of the fact that many of you reading this may enjoy running. This is logical; running is, in my eyes, the most essential or primal form of exercise, and uniquely accessible. (Do forgive my use of the word ‘primal’). Where other sports and forms of exercise require some extent of knowledge and training in a specialised technique, or an understanding of a conventional set of rules, running is almost wholly intuitive. Running for exercise and outside of a competitive environment is, for an able-bodied individual, natural and ingrained in a way that perhaps no other form of exercise is.

In America (1986), Baudrillard’s attempt at travel writing and cultural dissection of the U.S.A., about two-and-a-half pages are dedicated to the phenomenon of jogging. The Frenchman is, as usual, incisive and slightly obscure—for him, “Decidedly, joggers are the true Latter Day Saints and the protagonists of an easy-doesit-apocalypse.” For all its provocative flourish, Baudrillard’s analysis brings a unique cultural insight into a generally accepted practice; he sees jogging as symptomatic of a society brought to a standstill by excess, atomised individuals in a world of infinite abundance who can only find meaning through a machinic drive towards self-annihilation. The runner “has to attain the ecstasy of fatigue, the ‘high’ of mechanical annihilation.”

We live in a late-stage capitalist, white-collar world where there is essentially no need to physically exhaust ourselves for our livelihood. This chase for what I have been told is called a ‘runner’s high’ should be more strange to us, a kind of selfflagellation for a white-collar leisure class with nothing better to do.

I have at many times in my life wanted to be a Runner. A Runner (I am capitalising here to create a distinct term for this cultural identity), rather than a person who runs, is often spotted in an Instagram story with a pained-yet-sexy grimace accompanied by a Strava screenshot reading “cheeky 25k”.

The Runner may or may not be part of a run club with social media graphic design that is reminiscent of a Paddington small-plates concept café-cumwine-bar. In my pursuit of becoming a Runner, I often find myself late-night doomscrolling through the Nike web-shop convincing myself I need Eliud Kipchoge-approved $400 running shoes with a carbon-fibre midsole.

This cultural identity—performance as Runner— disintegrates when I actually go for a run. I put on the Oakleys, pop in the AirPods (after careful deliberation on a sufficiently ‘hype’ playlist with a tasteful mix of deep cuts and old favourites), and try to run. I tell myself:

I am Running. I am a Runner. I Run. I am shiny blue wraparound Oakleys streaking electric past you, a slovenly walker. I am a speedboat; I generate a wash of pure athletic sweat in my wake that passes over the lazy masses who I only see through the rose-tint of my PrizmTM lenses.*

*Designed and manufactured in an advanced industrial process to blur out people with a VO2 max below that of a semi-professional triathlete.

This delusion, I quickly realise, is completely

This delusion, I quickly realise, is completely incongruent with the actual embodied experience of running. My lungs howl and bay for air, the blood vessels in my legs go on strike, and my pores can’t keep up with the quantity of sweat my rapidly-rising core temperature demands of them. As each Nike AirTM cushioned stride contacts the pavement, my knees rattle under the painful experience of actual physical effort, and the idea of being a fleet-footed gazelle bounding through Camperdown Park in lime-green short shorts fades as I see spots in the corners of my vision. Running is visceral, physical, and gross; I am reduced to an animalistic state as blood diverts from my brain to keep my body moving. Like Baudrillard’s jogger, foaming at the mouth, I annihilate my thinking self in pursuit of a goal that doesn’t materially exist. I have no finish line or competition beyond an arbitrary amount of physical exhaustion.

~

Running and being a Runner are completely different things. Experiencing running is to live in one’s body, experiencing Baudrillard’s “mechanical annihilation”, becoming someone “cocooned in the solitary sacrifice of his energy”. Rather, to be a Runner is to only simulate this “solitary sacrifice”, to signify physical effort and performance through the semiotic system of run culture. (“It’s all semiotics bro…”: Roland Barthes, Mythologies, 1957). Purchasing the $250 MothtechTM t-shirt with performance-enhancing distressing or being featured on the run club Instagram story are just symbolic representations of actual bodily movement—they imply the activity of running; they signify that one runs. The most egregious of these obfuscations is the Strava activity: discontent with reality—the body’s experience of running—we need to translate our effort into a semiotic representation. Sweat, lactic acid, and exhaustion become numbers and orange lines on a map, christened with the offhand title “afternoon 5k”, which tactfully understates the difficulty of the run. The Runner sublimates their bodily exhaustion into an acceptable cultural representation of health, because this is the only wway we can reckon with the horror of our IRL bodies in a post-real society.

If a 5k was run in a forest without 5G and no one is around to give Strava kudos, was it run?

We can only run as a hobby because modern society has no need for our bodies; effort loses its productive value and now belongs to the domain of recreation. This is why the Runner exists. Being a Runner is a cultural performance that allows us to dissociate our bodies from health. Health is no longer a biological determination, rather, to cosplay as a healthy person is to be healthy. We are, for all social intents and purposes, healthy by donning activewear, by waking up at 5am to post a sunrise, by speaking about ‘carb-loading’, ‘interval training’, and how “I’ve been really getting into ice baths recently”. The total exhaustion of the self, the physical hurt and experience of running no longer matters; health is now totally divorced from the body.

Oddly, this makes me want to run more. When I feel so removed from my body, from the visceral feeling of being a fleshy human with various fluids and organs sloshing about in our skin, maybe I can see running, or any sort of physical action, as an act of rebellion. Baudrillard postulates running as self—annihilation, but this is an annihilation of the intellectual, thinking self—a ritual murder of our subject-selves to resurrect our bodies in a time when we discard them as grotesque and unmentionable.

We now move in hyperreality—a state where our social world is completely overtaken by representations of real life, and our reality becomes constructed of simulations. How do we resist?

By using our bodies, by moving and being in the world physically, running through hyperreality, we can perhaps regain bodily feeling, taking back reality from the hyperreal.

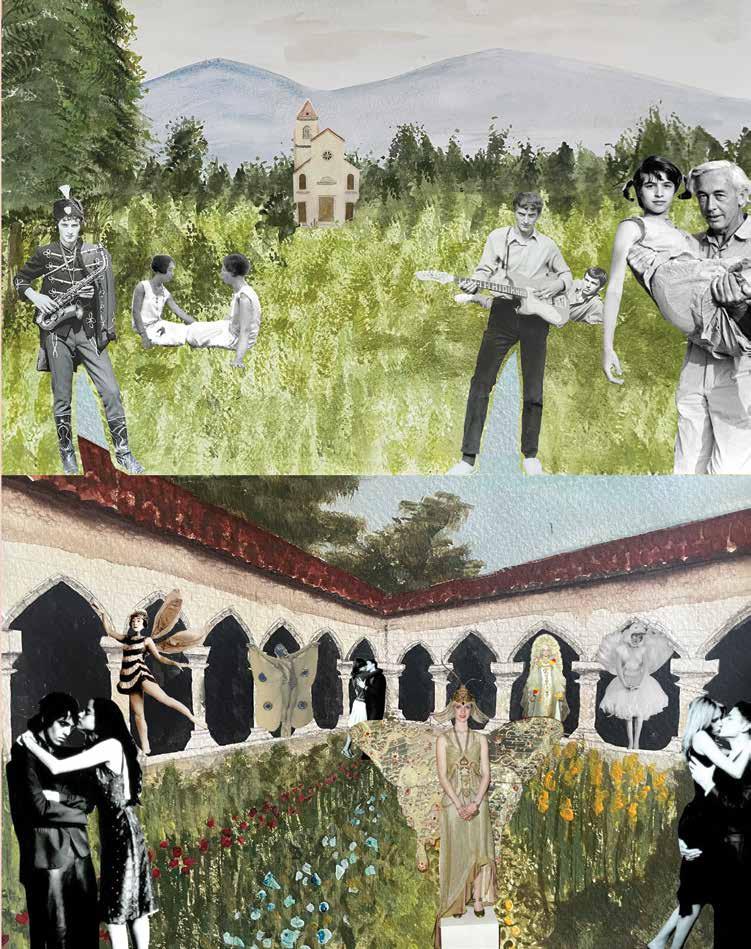

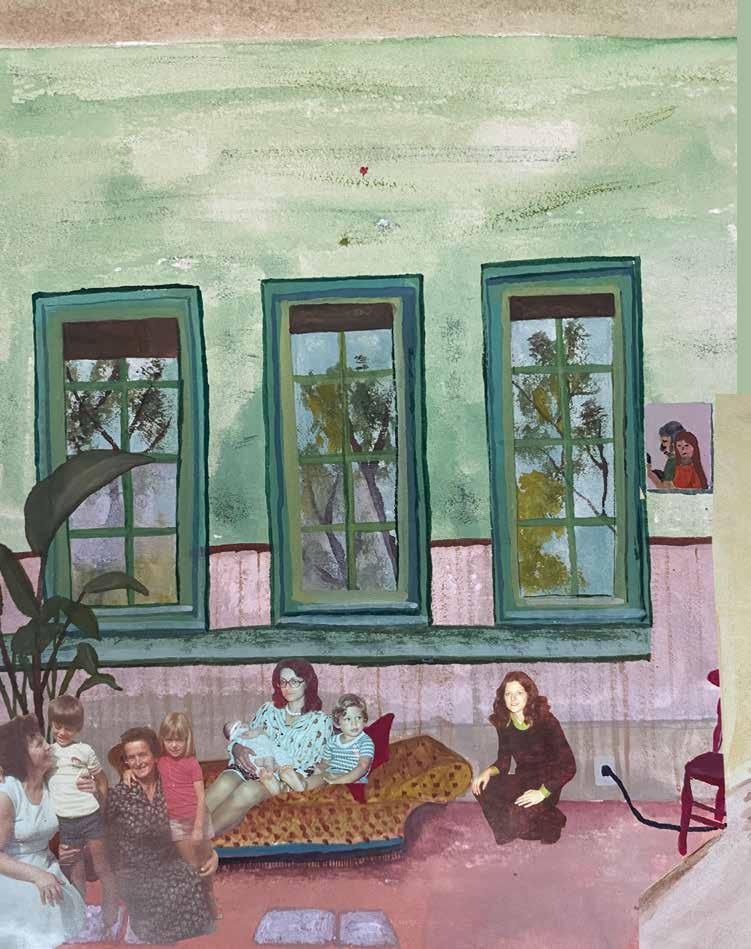

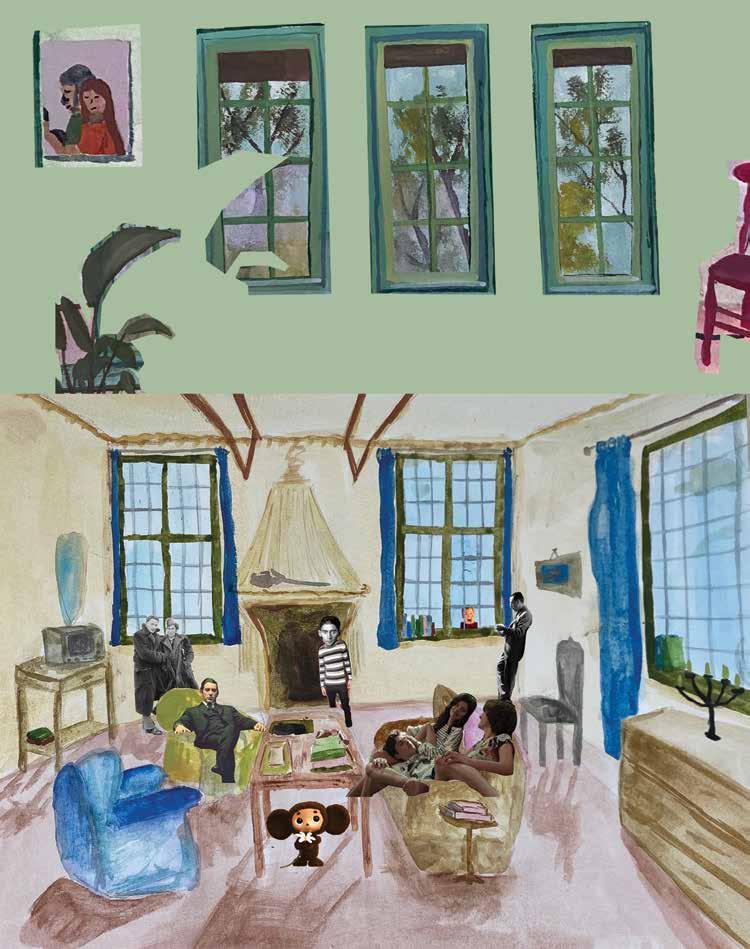

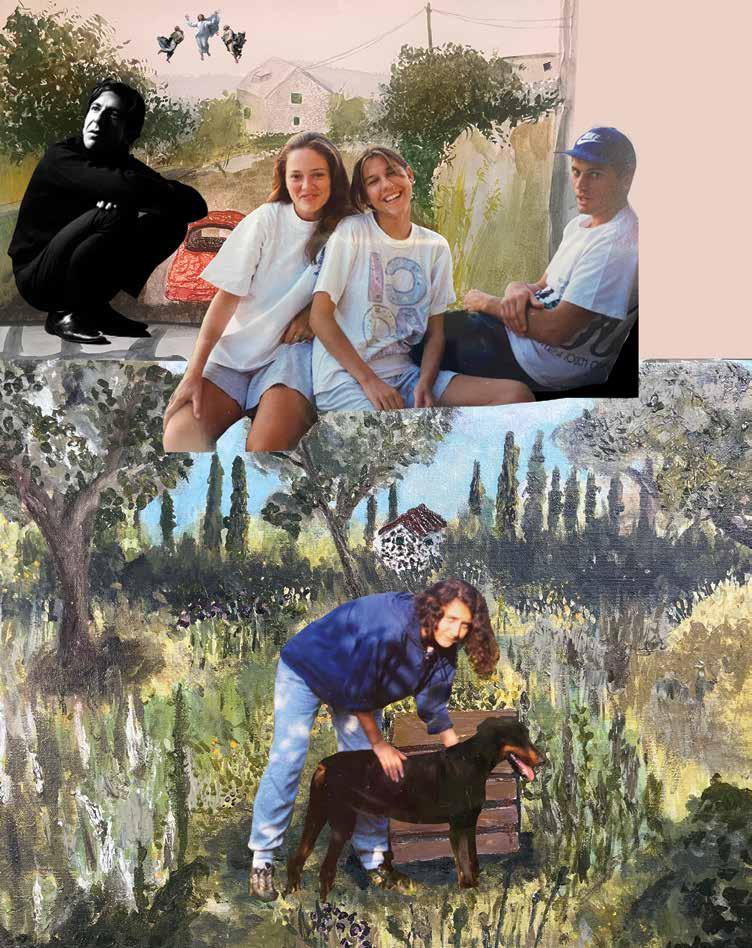

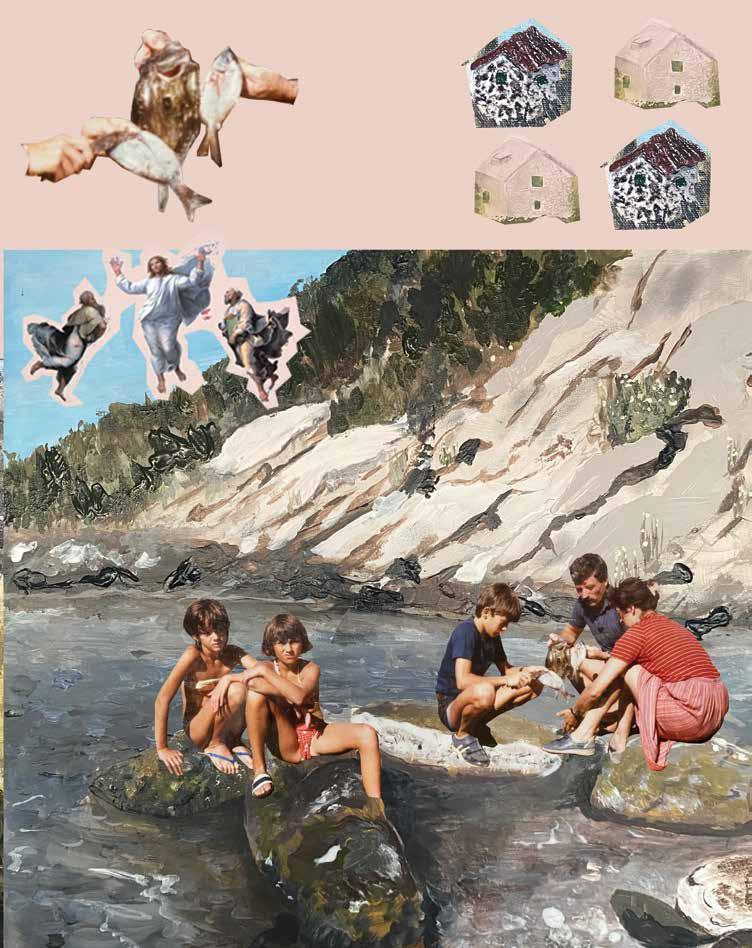

My collages integrate familial and well-known figures’ photographs into two-dimensional watercolour scenes. Interior spaces and outdoor landscapes are places where memories and media coexist. In some scenes, relatives loiter in open fields with celebrated authors. Ancestral history is estranged and abstracted. The scenes are pulled from my mother’s memories in Croatia, which was then a part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Personal history becomes a playground for imagination. As it does not involve me directly, I view memories of lost relatives as fictional scenes of mythical characters. Cutting and pasting these figures into bright spaces supposes they can be reborn into entirely new and fictitious narratives that I construct for my own amusement. The recurring motif throughout the works is the colour blue; sky blue depicts a washed out azure horizon, whilst royal blue, the colour of lapis lazuli, is a colour that I associate deeply with the sea. The collages can be read as love letters to the Adriatic, the sole force shielding the central Dalmatian archipelago from immediate destruction for centuries. In the ocean one finds freedom and eternity, a feeling I hope to encapsulate.

locker today. Ideally, I’d like to find one that is at eye level because I don’t want to bend down or have to tippy-toe.

What if the locker won’t lock and I will have to move all my stuff to the next locker after having stored everything?

No no, that won’t do. Should I use the bathroom before I undress? Otherwise, I will have to remove my shoes and the floor is dirty and ew, there is hair, and I don’t want to walk on it barefoot.

Did I bring hair conditioner? What if my goggles fog up today? Do I need to tighten them before I get in?

Can other people see the years of scars from falls and trips and stumbles on my knees? Surely, they can.

Why would they notice though? Everyone is busy focusing on themselves. I need to stop thinking people are even looking at me. Stop being so selfish. Stop thinking. Okay, I hope I can find an empty lane.

walking barefoot. I really should bring slippers to the pool. But the walk back home in slippers would slow me down. I am many things but NOT slow.

Alright, which lane do I pick?

Sigh, how I wish I could magically make a lane appear just for me to swim in.

Well, this first lane has someone swimming really fast and that could work… but then what if I can’t keep up the pace? Then he will eventually catch up to me and either he will have to swim around me and then I would be an inconvenience, or he will slow down behind me and I just know he will secretly hate me.

Perhaps no fast lanes. I don’t want to put that kind of pressure on myself.

Slow lane? But then I would have to constantly swim around the people in the slow lane.

I look straight down when I swim and I don’t want to accidentally hit someone’s foot. I hated when that happened last time.

Goddammit this should not be that hard, just swim. Okay, the medium lane it is, the girl swimming here seems to be okay.

Not too slow, not too fast.

Am I the… Goldilocks of swimming?

Now I just have to slowly get in the water but I’ll wait for her to start her lap so I have time to get in, I don’t want her to collide with me. By the time she’s at the other side I’ll have acclimatised and we can be perfectly paced to never collide. Like ships in the night. Okay, I can start now. Good start, I’m getting into a groove. Just one arm after the other. Hmm. Do the other swimmers know that I am probably not that good?

Are the coaches laughing at my form? No one is thinking about me, it’s okay. Breathe. Should I count my laps? Or will I get more tired if I count?

I really should swim more often and be able to do a hundred laps. If only I had more discipline, I would have better form.

I am a fraud.

Oh yay, she is leaving now, I will have the lane to myself and I can swim calmly.

Zen. Easy. Look at me, the pinnacle of all things good and balanced.

I love having a lane to myself—oh god there’s a man looking for a lane to swim in. DON’T PICK MY LANE. Should I pretend to be super slow to deter him? Or super fast? Do a butterfly stroke like a total maniac?

This is the problem, I am the problem. Sigh. I envy those who can just close their eyes and swim.

By Marc Paniza

The first time I stepped into Pavilion Mall in Kuala Lumpur, I felt both relief and unease. Outside, the air was heavy with humidity, my clothes stuck to my skin. Inside, the blast of cold air carried that special scent of disinfectant, fried food, and synthetic perfume which I have known since childhood. My friend turned to me and said the city felt hollow. Every place we went was just another shopping mall, and he was not buying anything. His words lingered in my mind because malls are never only about shopping. They are the plazas, squares, and meeting grounds of Southeast Asia. Yet, they feel like hollow spaces that alienate as much as they comfort.

Across the region, malls are the beating hearts of urban sprawls. In Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, Singapore, and Jakarta, they pull people in and manipulate daily life. Malls perform what Marc Augé calls “supermodernity,” producing spaces that are at once both personal yet impersonal. They are “non-places,” generic enough to be replicated anywhere, yet memorable for first dates, family Sundays, and the relief of air conditioning on a humid afternoon. They are Western-influenced by design, yet they have become deeply local in their function. Vast atriums, imported marble, international brands, and seasonal spectacles like Christmas displays signal a borrowed image of wealth.

These features reveal how Southeast Asian cities imagine modernity, equating progress with Western symbols of consumption.

Nowhere is this more obvious than the Philippines, where the mall has become the true public square. Manila is dotted with mega structures: SM Megamall, Mall of Asia, Greenbelt, Robinsons Galleria. Bag checks at the entrance create a sense of order, with uniformed guards who often appear more official than the police. Yet once inside, malls become endless playgrounds. There is always the waft of Jollibee fried chicken mixing with the industrial chill of the air conditioning. Karaoke booths hum with off-key ballads, cinemas are packed with people, food courts overflow with chatter, and entire generations of children grow up loitering between escalators and arcades.

The scale of mall culture in the Philippines is inseparable from Henry Sy, the Chinese-Filipino businessman who built the SM Investments empire. By constructing massive malls across the country, Sy not only created a retail business, he reshaped civic life itself. The mall substituted for the park, the plaza, and often the state. It offered air conditioning where the government failed to, and security where police protection was unreliable. During typhoons, malls served as informal shelters.

For many, these buildings supplied the basic goods of survival that the state could not. Yet they encoded inequality in their architecture. Glittering façades rise above jeepney terminals and sprawling informal settlements. Inside, staff hustle to meet sales targets while guards quietly remove anyone who looks unkempt or unhoused. To enter the mall is to step into a world of aspiration, one that is carefully policed.

In the 2025 elections, polling booths were set up inside malls, turning democratic participation into another activity to be slotted between groceries and fast food. Political presence is inescapable: faces of politicians smile from tarpaulins that congratulate students for passing board exams or wish entire districts a Merry Christmas. Imagine if Anthony Albanese plastered his electorate with “Happy Holidays” corflutes every December. In Manila, this is ordinary.

For visitors, the mall demands performance too. I grew up being told to dress up before going inside. It was not casual, it was ceremonial. In Sydney, people wander into Westfield in tracksuits. In Manila, entering the mall feels closer to entering church. What looks like civic life is in fact a selective performance, where comfort and exclusion are rehearsed together under the same roof.

Generational shifts in consumption patterns reveal that malls are not only vulnerable to economic change, but are themselves temporary solutions to deeper structural problems. Their profit declines expose the fragility of an urban model which relies on private corporations to substitute for public spaces. If the next generation continues moving its social and cultural life online, the hollowness of the mall’s promise of civic life will be revealed even more starkly.

My friend was right in his observation regarding Kuala Lumpur feeling hollow, but that hollowness should not be accepted as inevitable. The mall’s dominance reveals how political and economic development in Southeast Asia has often outsourced civic life to private corporations. Francis Fukuyama once claimed that the end of the Cold War marked the “end of history,” where Western liberal democracy and market capitalism would stand as the final form of human government. In Southeast Asia, the mall performs that fantasy in architecture, presenting consumption as the triumphant endpoint of civic life. Yet the hollow feeling complicates this.

Perhaps this empty feeling persists because what Fukuyama imagined as universal freedom has materialised as the freedom to consume, not the freedom to participate in public life. The mall represents the triumph of capitalism without the corresponding guarantees of equality or democracy. Public infrastructure has been neglected, and with it, the possibility of more inclusive spaces. To view malls as places of refuge from heat, storms, or extreme poverty is to confuse survival with so-called progress. My friend’s critique, taken seriously, calls for us to imagine a different path of development, one where the public square is not owned by the highest bidder.

Perhaps the best image of the mall is simply the most ordinary. A student, holding a bubble tea, sits under fluorescent lights while friends scroll through their phones beside them. Around them are Christmas decorations, already up in September, with a faint smell of Jollibee fried chicken drifting through the air. It looks harmless, even comforting, but it also captures what Fukuyama once imagined as the end of history. Here, the endpoint is not universal freedom or democracy flourishing, but a mall food court where civic life has been reduced to consumption. It is both hollow and alive, a refuge and a trap. For better or worse, this is the public square of Southeast Asia.

Amelia Elliott

Find a stimulus, or rather let it find you. Options include, but are not limited to:

A song

A smell

A photograph

A seat on the bus

A face in a crowd

An old shirt

A look your mother gives you

A shadow

Step 2

Be transported through space and time, find yourself in that moment again.

What faces, colours, places, do you see?

Linger in it for a minute more.

Step 4 Feel the memory’s touch. It may claw at your insides, hold your heart firmly, caress your spine, sending down a shiver. Don’t let this alarm you.

Step 5

Inject the memory with retrospect.

Step 6

(Note: this step is optional but usually unavoidable).

Consider your mother: How her memories shape your memories, how the memories of her childhood rest in your DNA. These things that happened long before you still exist within you.

i. Locate your mother’s influence in the selected memory. ii. Attempt in vain to cut it out.

Step 7

Spiral – what really happened?

Can memories lie?

Step 8 Return to your body. Notice your fingers, your fingertips. Aren’t they the invisible link between past/present, inside/outside, me/you?

Step 9

Observe the fingerprint this memory has left on you. Does the thought of this make you feel:

a. Loved

b. Tainted

If you selected a: wrap your arms around yourself and engage in self-embrace.

Created By Amelia Elliott

Starring Jess Crawley

Music by Henry Egan

If you selected b: scrub yourself clean.

Words by

It’s blue and wriggling. Why is it wriggling? Turn it off, I pray, please let it die.

“Is it freaking you out that this goes in my butt?”

“No,” a little, “that’s awesome, I’ve just never seen one for real… before.”

He presses it to my leg and I feel a trembling in my bones.

“I’ve washed it, don’t worry.” How can I not? I’m a germophobic traditionalist.

Silicone, especially matte silicone, is riddled with micro abrasions for bacteria to shack up and breed in. Also, you’re meant to replace these things. Often. I don’t think he ever has.

“But it’s good, right?” he asks, the top of the thing nestled in the gap between my hip and my vulva.

“Not bad!” I endure this for two long minutes before my prayer is answered. I welcome the silence like spring.

“I thought I charged it.” He apologises and I toss it aside.

“ That’s fine.” We go analogue.

The dildo is a troubling object. The horror second to uncleanliness is mimesis, its bizarre straddling of naturalism and abstraction. And following that, its destabilisation of gender and sexuality.

In his Countersexual Manifesto (2000), Paul B. Preciado urges us to unlearn illusions of what’s “natural”, and welcome organic, inorganic, or techno-semiotic prostheses. To treat the body as an interface, radically un-learn sex and gender systems in our binary-genital economy, reject reproductive determinism and the “naturalist” sexual agent. To become countersexual.

Countersexuality is post-industrial, global, and material: organ, flesh, flap, meat and molecule. It explores the body as a biopolitical technology with a prosthetic, symbiotic relationship to sexual instruments and apparatuses. Preciado identifies this process as “dildotectonics”. “Faced with this small object,” he posits, “the whole heterosexual gender-role system loses its meaning. When it comes to the dildo, conventional concepts and affects surrounding both heterosexual and homosexual pleasure and orgasms become obsolete”.

To the heteronormative sexual laymen, it’s a little bit of a shock when a lover asks you to perform anal sex, with an object that is charged (or apparently not) with so many implications; a silicone simulacrum that challenges collective societal norms as well as my

personal preconceptions about heterosexual sex. If there is this thing, why do we bother with the one that comes attached? And because this thing is attached to no one, is the pleasure it gives detached from sexuality? Does it depend on the steadying hand? Or the receiver? Is it a tool, a supplement, a prosthetic? A technology of production, power, sign systems and/ or the self? If I wield the object, what becomes of my identity? Despite my callousness, the object was a blue and wriggling catalyst for deep and distressing selfreflection.

I used to wear two sports bras to school, one forwards and one backwards, to cull the generous breasts my body cultivated at fifteen. I was the only girl in my year to wear pants when they became a female uniform option (gendered school uniforms, a polyester can of worms). There were days when I’d revel in the challenge I posed in a neon-pink bra that peeked through the pattern of my shirt, but it was more about the effect than how my body felt. I still get this feeling when I wear normal bras. Like I’m in drag.

“In imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself —as well as its contingency.”

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (1990)

Why does it feel like an imitation of gender when they’re the material sex characteristics I already possess?

“Well, actually, sex and gender are two different things” was a phrase often used by my high school peers. We separated them for affirmational purposes, for debates about trans rights held over sliced apples and Le Snak packets; a simple slogan we could sling back at our less tolerant classmates. Our intentions were good, but oversimplification is the devil’s doorway.

Judith Butler refutes notions of gender as purely a socio-cultural butter on a bio-sex bread. They go as far as to suggest that “sex” doesn’t exist at all. If sex, socially and culturally, is gender, then what is sex? The invocation of material sexual difference, i.e. your bits and boobs, is outdated, reductive and inaccurate. Currently, what isn’t binary is pathologized, despite scientific crisis in sexual difference since the 1950s. Butler argues that sex is a “regulatory ideal,” vis-a-vis Foucault, “forcibly materialised through time” through the reiteration of norms. Butler points out that their reiteration proves that they’ve never really stuck, and are thereby subject to change.

Gender performativity is a similarly reiterative practice: the sum total of mannerisms, clothes, roles, expectations, and utterances that we repeat or distance ourselves from. “By which discourse produces the effects that it names”, language simultaneously describes and shapes reality.

Simply put, Butler argues that gender is the product of repeated, ritualised acts that uphold societal norms, and not something one is. Preciado furthers this by suggesting that gender is also partially prosthetic, “sex and gender should be considered forms of prosthetic incorporation that pass for natural but that, despite their anatomicalpolitical ‘naturalness’, are subject to continual processes of transformation and change”. While this does not mean that we are fully in control or conscious of gender performativity, it does mean that doing gender differently can change its meaning over time.

It takes him a while to say it.

“I’m nonbinary.”

“Okay.” You can’t be.

“That was scary.” They stare into the lamp and purses their lips, the same way he does when he plays guitar.

“I’m literally reading about post-gender stuff,” I offer, turning my laptop toward them and reading out a few lines of Preciado. They laugh. Later, I ask about pronouns.

“He or they, both are good.” “Okay.”

Describing and shaping reality. I feel the couch shrink beneath me. It’s so simple, in theory.

I’m a progressive person. In theory. My best friend’s mum said his transition felt like a funeral, as if her daughter was dying. But he was standing right next to her, as my partner sits next to me now. There’s nothing dead about this. Instead, a peculiar feeling, like an ugly jumper shrunk in the wash, my semantic boundaries felt wrong. We are intimately involved, and as self-centred as it is, I have to wonder: how does this impact my sexuality?

Socially vested binary codes uphold “(hetero)sexuality” itself. The codes we know are masculine and feminine. While I understand that they’re illusory and to be dismantled, I have no idea what that looks like practically. Will he adopt more feminine codes? Are terms like “femininity” or “masculinity” even applicable?

Androgyny? When these codes are broken, pushed away or made defunct, what use is sexuality? When sex, culturally and socially, is gender, and gender is not only the result of ritualised acts, but a construction and a prosthetic, does sexuality become similarly ephemeral? How do you orient yourself without a position?

I try to take shelter in Preciado’s Dildonics, “the sexuality of the postgender and post-sexually identified subject” (not to be confused with Dildotectonics, mentioned earlier), which asserts that sexuality cannot be reduced to sexual difference or gender identity. Preciado likens sexuality to language, in which we are conditioned in monolingualism, but

multilingualism is learnable. Then instrument virtuosity: where some only play the piano, others treat instruments as means of music-making. It’s a communicative tool. But what exactly does it communicate? A material desire? Something reductively anatomical? Something pleasurably chemical? Or a preference of codes?

“You good?”

“I’m alright, this [bolognese] is helping, it’s just all getting a bit conceptual.”

“What is? The dildo essay?”

He gestures towards the kettle, and I nod.

“Yeah. I don’t think gender and sexuality are real anymore.”

“I don’t think a dildo is a concept. I think it’s usually pretty solid. Up top.” We high five.

“And so what?

Isn’t it freeing?” They pop two mugs on the bench and sort out teabags and honey.

“I don’t know.”

“You should read Simulacra and Simulation.”

We watch The Matrix (1999) instead. That’s what this feels like—bids at self-actualisation under an all-encompassing (but not inclusive) regime. I’m waking up, wiping the ooze from my face and taking a glimpse at the hidden structure of everything. The splinter in your mind, says Morpheus. A prison you cannot smell or taste or touch.

Societal acceptance of nonbinary gender is only budding. But more interesting is the nonbinary “structure of feeling”, or present-tense emotions, consciousness, and affect: what is being lived today. I am a witness, and the act is infectious. Like how watching someone hold their breath makes us conscious of our own—I was now breathing manually.

“Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is, you have to see it for yourself.”

Wachowski, The Matrix (1999)

“Did you want to try she/they pronouns?”

“I think I have to investigate it somatically before I think about it semantically.”

I bought a binder on Wednesday. Spent a long time staring at the checkout screen. They said delivery would be low-key, using unmarked packaging and a false sender.

I live in a student share house in the Inner West—I could order a dildo the size of a Christmas tree and we’d all politely adjust to living around it, like our pile of recycling— but it indicated my own privileges. Preciado, buying testosterone on the black market to

avoid government restriction. Butler, criticised for either inventing or destroying gender.

My lover, gazing into the Matrix and uttering their identity aloud, if only quietly.

“Did you notice?” I gaze at our touching chests. “Oh! It came!” He steps back and takes in my altered shape. “You look boyish.”

“Yeah?” I almost hate how excited I sound. I don’t want to be a boy. Breasts just don’t align with my self-image. “You look hot.”

Hm.

Preciado treats the body as an infinitely graftable, changeable, chemical, animal thing with capabilities more complex than what binary, monosexual culture reinforces. An archive, a tangible chronicle connected to all history on a molecular level.

The binder pushed my breasts to my ribs and my idiosyncrasies to the fore: my moustache, a permanent shadow; an unattackable, infinitely renewable thing, sponsored by PCOS, felt more intentional, and my dress sense felt less tomboyish, more just boyish. I held myself more upright and the space I commanded grew, despite physical minimisation. Worst of all, it felt indulgent. But my experiment culminated in a frantic waxing session in our broken-bulb bathroom, where, cupped in a pushup bra and candlelight, I wanted to be a “girl”. And it worked, for a few hours, until I, top lip still bleeding, dug the binder out of my laundry pile and wrestled it over my head.

I found myself at an impasse, stuck in a holding pattern. I had been doing it wrong for a while. My performance was obviously flawed. The set lights and cameras and boom mic pushed themselves into my skin and face and hair and I couldn’t ignore them anymore. I had come face-to-face with the wriggling countersexual prosthetic, the utterance, the ephemeral and illusory codes of “nature” and their undoing. I pontificated and ruminated until the foundations cracked open and the Matrix poured out in slime and undulating lines of green code. Maybe the dildo was my red pill/blue pill moment, but instead of choosing, I coughed and spilled my glass before leaving Morpheus with blue balls and a dissertation on pills. I did the theory.

“I think I intellectualise where I should just experience.” “Hm.”

“But I want to understand everything.”

“Yeah. I think you should stop reading and stick a finger in my butt.”

In the early hours before Hội An awakens, a dim noodle workshop pulses with quiet and tireless labour. Inside, the air is thick with hot smoke from wood-fired steamers. Layers of soot cling to moisture-stained walls, marked by decades of steam. It is 4:30am, yet four family members have been working since 11:00pm, moving with alert precision while the city rests.

Their labour is steady and unrelenting. The dense, boiling mixture of ground rice and nước tro (lye water) is stirred evenly and pounded into dough. Slabs are steamed over fire, cooled, kneaded, rolled out by hand, cut into noodles, and arranged on bamboo baskets lined with banana leaf for a second steaming; a sequence that runs like clockwork. By 6:00am, trays of fresh noodles must reach breakfast stalls before the streets fill with hungry crowds. Movements are synchronised and fastidious, a choreography rehearsed over generations. At seventy-two, patriarch Mr. Em has carried out this ritual 364 days a year since age twelve. He is the fourth generation to tend the craft of hand-making Hội An’s cao lầu noodles.

Mo noodles are the heart of Hội An, kept alive by the town’s natural resources. Dough is made with water from local wells, rich in alum and calcium, blended with the ash of native Melaleuca cajuputi trees. These elements give the noodles their smoky, earthy flavour, yellow hue, and distinctive chew. In their true form, cao lầu noodles cannot be replicated outside of Hội An.

The noodles themselves bear marks of the careful, hand-made process; each strand varying in length and thickness, some tinted with a soft green from being steamed over banana leaves.

But in the shadows of the noodle workshop lingers a quiet unease, a weight that sits on Mr. Em’s hunched shoulders. His family is one of the last to make cao lầu noodles this way, the next generation is unlikely to continue. The greater prospects of Hoi An’s modern economy pull young Vietnamese away from the sleepless, backbreaking work of a cao lầu maker. Even once-loyal vendors and restaurants now choose cheaper factory-made noodles: perfectly uniform, coloured with artificial dyes, and bulked with tapioca starch. To those who grew up on real cao lầu, the imposters are obvious. But for passing tourists, these differences slip by unnoticed. And with factory production that can be done anywhere, there is a future where cao lầu is severed from the wells, trees, and workshops that once bound it to Hội An.

I am drowning under the river red gum, slipping between mud and silt—who can tell the difference? In this half-light, the river seems ungrateful, it slides its jaw against my feet.

Yes, I have made worse decisions before.

Tonight I decided to slip beneath your forgiveness. I made this declaration as your knee brushed against mine, as you gnawed

at your straw; the pause as your chipped tooth scraped against plastic and accused me of inertia. Again, I failed to divert this moment into something more.

My pulse intertwined with the worst guy at the pub, slumped on a barstool past the curve of your ear. He was muttering just lay off, I’ve had a hell of a day into his fourth Pilsner, barking oh fuck off at the crawling figures on the TV.

I could go for a beer. I don’t drink beer.

His spittle snakes down the rough slabs of bark. I hear his grunts in the humming earth. We eke out what we can get.

This is the season of crushed dragonflies.

The woman across the river has her lips pressed together like an envelope she is struggling to rip open.

I saw her prophesied in the posture of the woman at the back of the pub, head in hands, sucking on a lemon rind.

Now she huddles in the mud. Her teeth clack like clamshells—you cannot shake her.

She is not that good-looking but…there is something in the way she scrapes against the riverbed. Her shoulder blades fan. Her skin is electric. She settles above the crustacean’s head.

I can hear her almost, halfway—

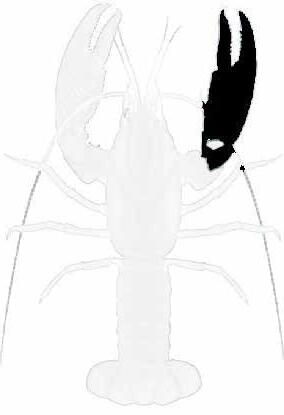

“Every man is a yabby, and you are the current above his head.

He cannot tell you the difference between fisherman and moonlight, between nursing hope and giving way to the pulling.

He has yabby-sick in his mouth, feeding on dead and decaying matter— this is one joke.

Another:

he is caught by a National Geographic photographer, who tells him to pose chin up, like you’re tasting something real good, and so he places his claws against his head.

He will reach out to you for clarity, to cleanse him of the filth of an ephemeral waterway that he could never outpace, to enclose him in something gentler, ready to yield.

You will find him in the grotty pub bathroom, curled in the toilet bowl.

You will keep him ungodly.

He is a good catch. He will squirm half-realised under your thumb.”

Upon entering her mock prison cell, Nadya Tolokonnikova let out a guttural shriek. Her voice reverberated through the installation, layered with eerie lullabies, climaxing into harsh bursts of noise. Occupying the central cell, Tolokonnikova was dimly lit by neon light, adorned in a forest green Adidas jumpsuit. Visitors were prompted to inspect and surveil the scene. Bed sheets made by American and Belarusian prisoners lined the walls, and the space came under each character's gaze. The performance, Police State (2025), bore a tension between prison and sanctuary.

Tolokonnikova is an artist, activist, and founder of Pussy Riot; a Russian performance group founded in 2011. Pussy Riot has relentlessly exposed Russia’s government corruption. In 2012, Tolokonnikova was incarcerated for an anti-Putin, balaclava performance at a Moscow Orthodox Cathedral, titled Punk Prayer. During her imprisonment, she went on three hunger strikes and published an open letter describing “slavery-like conditions”. In 2023, Tolokonnikova’s installation, Putin’s Ashes, at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in Los Angeles, landed her on the Russian most-wanted criminal list. Tolokonnikova has since lived in exile, moving around perpetually without disclosing her location. From June 5th to 21st, 2025, Tolokonnikova was subjected to another type of surveillance—a jail of her own making, Police State. At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (MOCA), Tolokonnikova existed in a corrugated steel replica of her Russian prison cell.

Untethered to materiality, Police State defied convention. The oeuvre of performance art is composed of audience and artist actions. Without a physical product, performance art is not marketable. In 2016, theorist Jonah Westerman remarked, “performance is not (and never was) a medium, not something that an artwork can be but rather a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world.” Thus, Police State was a site where the observers and the observed existed in a perpetual dance of oppression and resistance. The effect was a critique of autocratic surveillance.

The audience was embedded within Police State. Visitors pressed close to the steel cage, where large slits allowed a glimpse of Tolokonnikova. Others examined her through a security camera, replicating autocratic CV surveillance. In either case, they were implicated in the surveillance—a dynamic that would have been further heightened if Tolokonnikova could have realised her plan (discarded for liability reasons) to build watchtowers for visitors, literally placing them in the hyper-vigilant prison guard position. The audience was confronted by their own voyeurism.

Ordinarily, we are inundated by passive imagery upon entering a gallery. We can easily glaze over meek abstractions and crowd-pleasing landscapes. Commercial galleries’ collections fold into minimalist interiors, lulling us into passive states of low-impact consumption to maximise profit. The bureaucratisation of public galleries’ stifle their objectivity. Contrarily, Police State necessitates a reciprocal exchange between the viewer and the performer, which Walter Benjamin defined as “aura”: the integral essence of an original work that fades in reproduction. Witnesses observed Tolokonnikova’s proceedings, outside of reproduction as only existing in the present, then becoming memory. The in-person viewership reacquainted the audience with the auratic details of Police State, before it wilted. It denied the audience passivity.

The performance’s backdrop made Police State’s urgency particularly poignant. On the fourth day of Police State, a police stampede penetrated the installation space. Police helicopters hovered overhead the sprawling Los Angeles streets. An officer delivered an order to disperse through a loudspeaker. Donald Trump had instigated a clash between U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, members of the California National Guard and anti-immigration protesters. MOCA was closed, barring audience observation. Tolokonnikova continued her performance in the empty museum, posting on Instagram: “Police State exhibit closed today due to police state.”

“I felt I had entered a wormhole,” Tolokonnikova recalled following the 2025 L.A. riots. The parallels between Police State’s closure and Tolokonnikova’s first arrest are sinister at best. For the final duration of the performance, rather than show prison recordings, she live-streamed audio of the protests outside into the mock cell. The present penetrated Police State, which was initially a reckoning with Tolokonnikova’s past. Autocracy protrudes in both scenes.

America has feigned values such as freedom and democracy; thus, for privileged white Americans, the idea of living in an autocratic society was previously inconceivable. However, as Tolokonnikova quipped, “authoritarianism is like a sexually transmitted disease—you have it before you know it.” And suppose we understand authoritarianism as the rule of a single party or leader that deems itself infallible, the Trump administration meets the criteria. With a totalitarian thrust, Trump began his presidency by stripping art centres and universities of funding. Pervasive immigration reforms have prompted mass expulsion. Reproductive rights have regressed. The transgender identity remains precarious. Compromised bodily autonomy has made performance art pertinent.

The performance genre makes a lasting impression beyond cursory engagement. Police State (2025) viscerally alerted its audience to the resemblance between Russian and American autocratic tactics, when most artistic mediums fall short. The piece immersed viewers in a critical fabulation, and rendered palpable the artist’s lived imprisonment. Tolokonnikova has earned our attention.

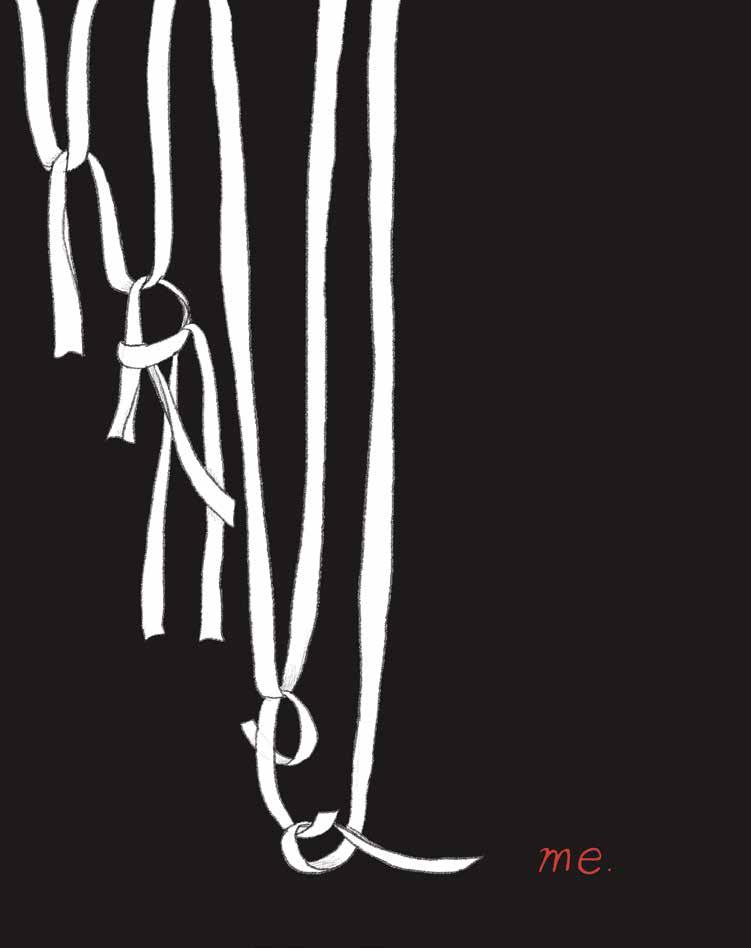

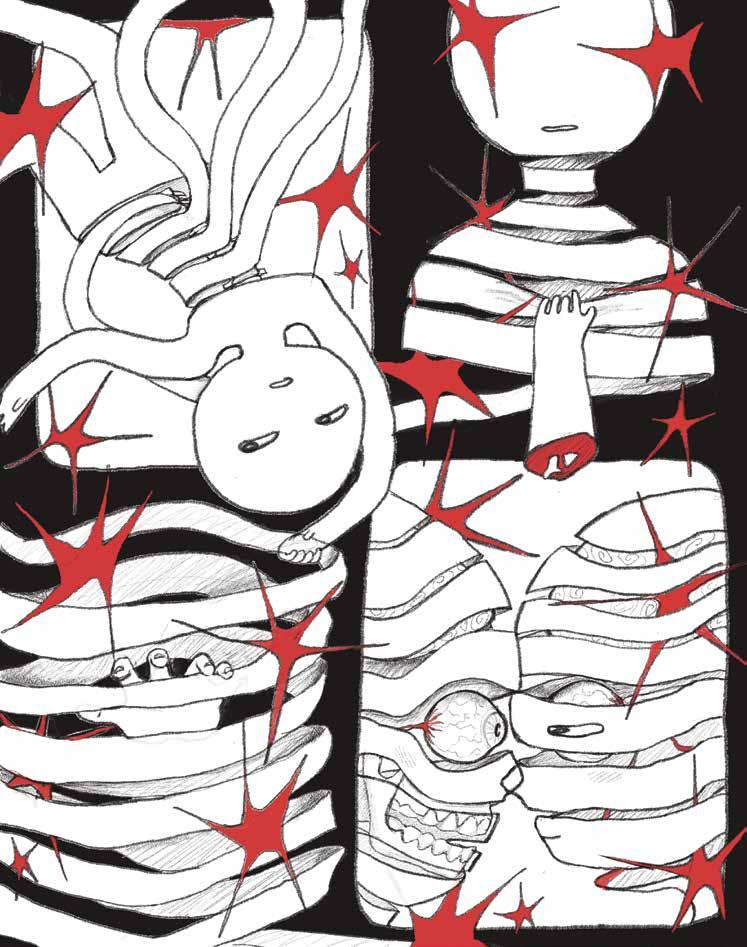

Sophie Wishart

Unravel Me.

Is it so much to ask? Is it soooo much to ask that I could just crawl inside, just a little bit, just politely burrow into your ribcage and warm flesh like a fox preparing for a harsh winter? Or maybe that’s too gory for you, FINE! Maybe we could just phase our atoms together then? Just a little bit? I think if we vibrate at just the right speed we could—no? Hmm. Maybe you eat me then? I could slither down your throat super easy, honestly you won’t even notice me! Come on!! Do you even love me?

I believe that I maintain the right to be personally offended that I cannot merge with my boyfriend. This is what Unravel Me is about, the expression of my unmet desires. The constraints of tangibility truly plague my waking days. Holding hands is not enough, being in the same bed is not enough, lying on top of me with your full weight is nice, but not enough. I’m a complete greedy guts, and ungrateful too. I should be able to cry and gently scratch at the offensive skin that dares to stand between me and the ribs and flesh I deserve to be able to nestle within.

I would like to pretend Unravel Me is a visual love letter, and it is, but it is mostly a formal complaint.

Matilda Azmi

I’m being fed this creator’s short form videos where he turns his New York apartment into a makeshift cafe, baking sweet and savoury treats once a month for his friends and neighbours. Recently he has branched out into three course dinner parties and birthdays. As I watch, I find myself salivating, not over the food but over the fact that this individual has so much time. And I’m addicted.

The creative I reference here, Ryan Nordheimer (@ryannordheimer), posts videos showing himself, in quick, attention-grabbing shots; rolling out pastry, whipping multiple flavours of custard and cream, piping macarons and profiteroles, boiling lobster, marinating, dimpling focaccia dough, pickling, proofing and preserving. Each shot is no more than a second or two long, and he quickly pulls together four, five, six—even seven—recipes in a single video. Of course, I could argue that the fast paced video is meant to grab and keep your attention, as most short form videos on social media do. The content is instructional and tells you how to complete the meal you see. “You can find the whole recipe on my website,” Nordheimer says at the end of his videos. But what everyday consumer of social media (me, a student) owns a mortar and pestle?

The style of these videos presents to the viewer a doctored version of reality. It’s not actually that easy to cook a three course meal. Watching the video on your phone is one thing, but actually doing the cooking is another.

Nordheimer’s videos have an aspirational angle so that the consumer will interact with the content. When I save the video for later it gives the content more traction in the algorithm. Shock, horror, I will never be making any of these recipes.

These selling techniques, which create an object of desire and something to aspire to, have been used before. Don’t let older generations tell you you’re only being sold unrealistic standards now. For instance, the famous and coveted Eames lounge chair which was released in 1956 was designed by the husband and wife duo Charles and Ray Eames. It is a plywood and leather recliner chair that you can sit in while reading or watching television, which is something you might do if you have the luxury to take time to relax and enjoy yourself in your designer chair.

The Eames lounge chair was designed and marketed in post-war America, which was of course characterised by hyper-consumerism and the nuclear family. The 50s was a time where people (men) would expect to be rewarded for their hard work and receive a promotion. Unlike previous generations, upward mobility allowed families to move houses, possibly multiple times. The Eames chair was marketed as an aspirational piece of furniture that, given its easy construction, would move with the owner to new houses as they climbed the career ladder. These themes continue to be relevant today as contemporary media feeds off the lives we inhabit online and the high standards we attempt to mirror.

Charles Eames famously said that the leather was designed to soften over time, developing a worn patina similar to “the warm, receptive look of a well-used first baseman’s mitt”. The mitt has western values America stands to represent like meritocracy and masculinity stitched into it.

However, The American Dream has been widely criticised as being an unattainable lifestyle based on capitalist work ethic and it ignores systematic disadvantages that are structured into both public and private organisations and institutions.

The Eames couple also developed a three-and-a-half minute ad which was shown on a daytime television program, Arlene Francis’s Home in 1956. The ad showed a simple man building the chair. With a stop motion style, elements would miraculously appear in the man’s hand, jump to the base of the chair and be screwed on in the next shot. A spanner appears out of thin air and the chair is built in the first two minutes of the video. The man sits in the chair once complete and his outfit changes to a sharp suit. After spending some time in the chair reading a newspaper brought over by his wife, the man changes back into his t-shirt and disassembles the chair. It is packed up into a brown moving box.

The style of the video provokes a sense of aspiration within the viewer, depicting an ideal western narrative that is associated with owning the chair. As the chair is so easy to construct and deconstruct, it is made for moving house, to move with you, the design itself, paired with the video’s style, provides to the average consumer a lens through which to view the chair.

By making things look simple, the Eames couple were able to feed off of the newly established social order.

I work and I study and I go to class and what I do not have, what Ryan Nordheimer does have, is time. I wouldn’t be surprised if he had a luxury recliner in his loungeroom. The people we see online who have an immense amount of time to curate their lives sell what their audience can never have. The consumer thirsts for the way an item will make them feel, and like the way the Eames chair was able to be sold at such a high price point, a short form video provides a quick snippet into an unattainable lifestyle dangled cruelly in front of you. In the attention economy, where my time is so valuable to companies and individual creators, I find myself not going into my own kitchen, but staying in bed and looking at other people’s lives online.

The content I consume, which curates a life to aspire to, is slowly decomposing my sense of achievement and satisfaction.

It has been well established that content on social media is affecting the way young people think about themselves and their self-image. It’s not like I need an original 1956 Eames lounge chair to feel good about myself. Do I?

Am chef să mă piș

Vreau să mă piș oriunde ar trece Deci, Traiectoria pișatului meu; Funcția parabolică a liniei mele de piș.

Mă simt atât de bun când mă piș, atât de bine e ca și cum sunt o midie zburând în aer, eliberată din ghearele unei păsări pișăcioase— O pasăre care pișează pe capul meu mereu.

Iar acum, în gravitate zero, Căzând la o rată de nouă virgulă opt metri pe secundă pe secundă, Fiecare secundă la pătrat, Mai am trei sau patru minute să mă piș,

În aer liber, neaglomerat, Peste capul nesimțiților de jos Care cumva reușesc să se piș pe mine chiar și acum când cad la velocitate terminala; Care o să trăiască mult mai mult decât mine, O midie pișăcoasă în aer liber.

Prin fum de petrol și gloanțe și bombe nucleare, Ei supraviețuiesc orice, boss, da Și acum într-un minut sau o secundă ei toți o-să sărbătoaresc cu carnea autotocată si pulgeratâ de midii— ne-inclusiv midia.

Dar întâi, sunt aici, În aer liber, liber și curățel, Care îmi dă acum timp, chiar niște secunde sa ma piș peste capul lor, cu chef adevărat.

Cosmin Luca

I feel like taking a piss. I want to piss no matter where it goes. That is, the trajectory of my piss, the parabolic function of my stream of piss.

I feel that good when I piss, that good as if I’m a mussel floating in air, liberated from the talons of a pissy bird— a bird that pisses on my head always.

And now, in zero gravity, falling at a rate of nine point eight meters per second per second, each second squared, I still have three or four minutes left to piss,

In the open air, uncrowded, over the heads of the bastards below me, who somehow manage to piss on me, even now as I fall at terminal velocity; who will live much longer than me: a piss-prone mussel in free air.

through petrol fumes and bullets and nuclear bombs, they survive everything, boss, yes, and now, in a minute or a second, they will all feast on self-minced and pulverised mussel meat.

But first, I’m here, in the free air, free and clean-ish, which gives me some time, a few seconds more, to piss over their heads, with real feeling.

Nathan Philis

My first memory of ‘body swapping’ media was in 2009, sitting across from my pink PlayStation 2, gleefully watching the first live-action Scooby Doo (2002)1 movie on an archaic Panasonic TV. For those (un)lucky enough to be uninitiated, 54 minutes into the movie—following some quintessential children’s cinema nonsense—Fred body swaps into Daphne. This wasn’t a revolutionary moment for me. Nor was the titular transformation in Mrs Doubtfire (1993)2. Nor the Copeland brothers' covert manoeuvring in White Chicks (2004)3. Because body swapping and cross-dressing in this era of mainstream 2000s Western media wasn’t made to be about gender exploration. It was made out to be comedy.

Purely based on the age of the average 2025 University of Sydney undergraduate, most people reading this would have been born between 2000 and 2008. Thus, I can infer that, many of you probably grew up on similarly clunky media. Better yet, with the above anecdote in hand, you may already have a handful of deeply nostalgic films in mind. You will quickly realise how many men in dresses were used as comedic characters.

I also grew up in that era. Whether it was watching She's The Man (2006)4 during a rained out high school P.E. lesson, or viewing a rerun of M*A*S*H (1972)5 with my dad, my exposure to queerness—before I even had a name for it—was trivialised by that cultural climate.

However, there is a dissonance here. These films and TV shows can be dismissive and openly harmful—our Scooby Doo case for one. But on multiple occasions, I’ve been blessed to have a queer man fondly explain the campness of The Birdcage (1996)6, or the charm of Mrs Doubtfire (1993)2. It’s not just Robin Williams; beyond some exceptions like I Saw the TV Glow (2024)7, it’s incredibly rare in my circles for a piece of modern queer media to reach this kind of cult-classic status. Whilst there are several factors at play here, I would like to make the following argument:

When Western media treated gender fluidity as a vehicle for jokes, it clearly fuelled homophobic and transphobic discourse. However, the perceived apolitical nature and frequency of cross-dressing under this toxic environment meant that such representations became common, making gender fluidity more uniformly visible in the mainstream than before. Cross-dressing was an act not just for the queer, but for everyone. Talk show hosts and celebrities could frock up, act, put the dress back on the hook, and hide behind the role as cis as the day they were before. You could see casual queerness on the news, in comedy, or in children’s TV shows. While it was certainly portrayed in a toxic manner, the queerness was accepted as a normal part of the role.

What speaks to me about this clunky 1980–2010 gender swapping isn’t the nostalgia, it’s the indifference. In these films, I saw myself and my queerness, paraded by other cis men. I dearly hope that one day Hollywood will reclaim that uniform ease of presence around gender fluidity, matched with the accuracy, acceptance, and compassion that contemporary media has been carving out for it.

If you know me in real life, you'll be in one of two camps. Either you will have seen me in a black mesh top and dreadfully smudged eyeliner, screaming at Birdcage, or you will have seen me with a crew cut and an AFL jersey, about to take to the field. Compartmentalised by design. If I had to hazard a guess, it would be that many of the people I meet in my life are also a lot more fluid than they appear.

Queerness is more broadly, accurately, and healthily covered now as compared to the 1990s and early 2000s, but a part of me misses seeing gender fluidity unabashedly touted by everyone in the Hollywood mainstream. Whilst the death of gender as a laughing stock is certainly healthier and better than Daphne in a red ascot, I will always be delighted by Bugs Bunny playing a woman flight attendant8. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

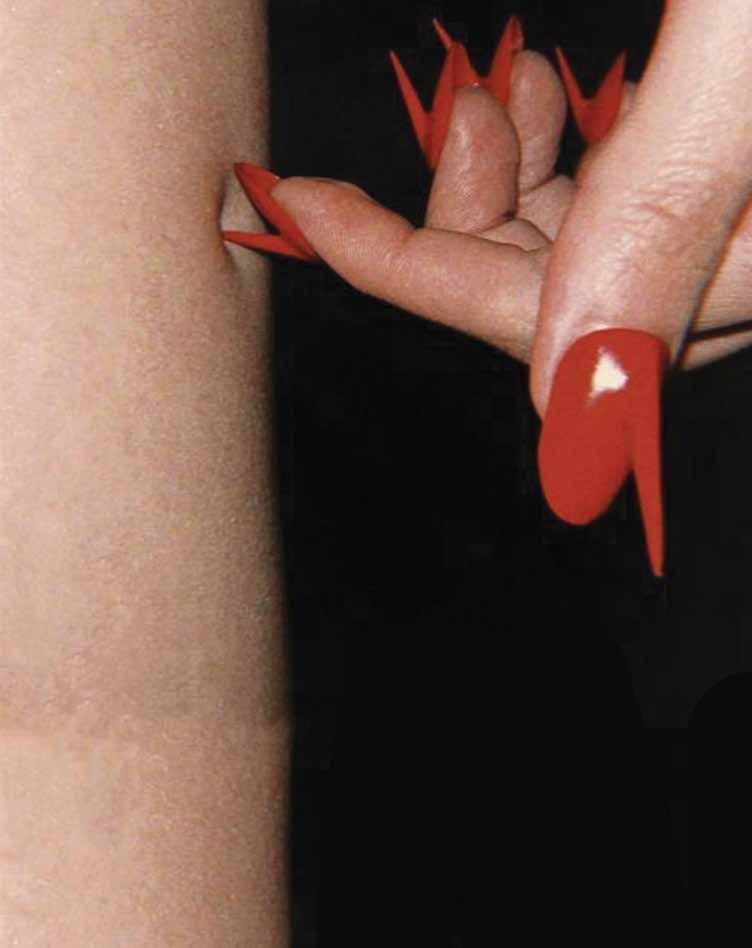

Allegra Pezzulo

Desire is rarely clean. It leaks, it clings, it stains. Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject names the collapse of boundaries between self and other, inside and out, where figures in transition resist categorisation. More than disgust, the abject unsettles by exposing the fragility of identity, bending rules and casting prohibitions aside. What seems like charm or chance encounter corrodes into fixation, possession, consumption. She moves, speaks, forgets; yet the narrative bends toward his hunger, his projections. Here, intimacy becomes contamination, and desire, erasure.

“Tall flat white with caramel. Uh, Skim Milk… No, I don’t want foam. Thanks.”

He said it in between breaths and an uncomfortably loud phone call. His voice cracked on skim. He wore a navy blue suit, an Omega watch, a black tie and silver cufflinks. His hair combed back conservatively. His stance prideful as if to separate each vertebrae and place them apart. A man, ordering dignity with caramel syrup. Charming.

She stood behind him in line, a balancing act of deciding on her order while listening to the conversation of the man before her. He was loud but not urgent; he wanted to be overheard. “Tell them we’ll restructure, but don’t mention compliance yet,” he said into the air, as though the café were a conference room. She thought she knew him, faintly—the suit, the gleaming watch, but couldn’t quite press the tip of her finger on the memory. Maybe a face from a meeting? Maybe from nowhere at all.

As she stepped forward, he took in her elongated frame. Soft hands with sharp French-tipped nails. He always liked the look of a fresh manicure on a sophisticated woman. Even more so, he liked the image of those nails dragging across skin, leaving crescents of blood where polish had chipped.

“Iced Americano with a dash of milk. And... perhaps a bagel. A sesame with lox. Thanks.” It was sacrilege to order otherwise. Bagels without lox were counterfeit. Her mother had told her so, in one of those hand-me-down cultural edicts, three things were certain: bagels are not to be scooped, and above all must have lox. Her mother had also told her never to trust a man who wears a navy blue suit to work, not even Anderson Cooper, despite (or because of) her inexplicable fixation on his T.V presence.

“Crazy you even have to say you want lox,” the man chimed in. His voice, loud enough to suggest he was waiting for her response. She glanced over her shoulder. He smiled, teeth shining. Too straight. Bad sign.

"The ultimate sign of New York City gentrification,” she said, accent trailing behind her teeth, Queens-born. He smirked, enamored with the cliché uppiness to her voice. Later he would remember the phrase not as a sentence, but as the shape of her lips when they formed gen-tri-fi-ca-tion.

"I’m from Buffalo,” he muttered with mock sheepishness, though it carried a strange pride, as if Buffalo itself were an inside joke. They shared a momen—or rather, he thought they did. She looked away quickly. He lingered. What she didn’t see: his gaze fixed not on her face but on the way she pressed her thumb into the counter as she waited, leaving behind a faint grease mark. He imagined folding that mark into his pocket. Keeping it like a pressed flower. Later, he would walk past the counter again, checking to see if it remained. The smudge became a fossil of contact, an oily secretion congealed into permanence.

Don’t worry, I’m one of the good ones.

Their names were called. She took her drink and bagel in one hand, slipping her other arm through the purple knit she carried. She brushed past him with the faintest smile, already forgetting him.

He stayed behind, fingers grazing the counter where the grease spot had been. Moist, still. Warm.

Later. A bar with too much glass, the kind that reflected everyone back at themselves. Their companies were ‘partners’, at least on paper, though he had never crossed paths with her formally. Coincidence, he told himself. Or inevitability.

She was already there, talking to someone from finance. Mark, or maybe Mike. It hardly mattered. Finance guys were all cut from the same sheet: straightlaced, boring, ambitious in the way that crushed the life out of everything. Mark’s hair was slightly wet, maybe even oily. Mark leaned close when he spoke, too close, his eyes crawling over her blouse. His laugh was damp, sticky. Mucus clung somewhere deep in his throat.

Men like him only knew rhythm and collapse, movement without imagination. She would lie there waiting for it to be over, her lips pressed together so they would not groan in disappointment.

She lifted her glass, set it down, lifted again. Three sips in five minutes. He counted them, quietly, like beads on a rosary. This is something Mark would not notice. She adjusted her necklace, the fine chain catching the soft light. He felt it as though she were tugging at his own collar, tightening it around his throat. He imagined it marking her skin, leaving a faint groove. He pressed a finger into the ring of condensation left from her glass on the bar and, when no one looked, touched it to his tongue. Diluted gin and lime, faintly sweet, faintly metallic, faintly her.

They locked eyes in the mirror.

He edged closer, letting the moment tip toward coincidence. “Funny, isn’t it, how we’re partners and yet strangers,” he said.

She tilted her head, squinting slightly as recognition bloomed. “The bagel guy.”

He laughed, feigning bashful charm, though inside he was thrilled she remembered. He had replayed her accent in his head for days. The way her lips had rounded and jutted out when she said gen-tri-fi-ca-tion had left an imprint, like teeth marks.

She asked about his work, and he gave answers too long, always circling back to himself. He told her a story from childhood, about collecting scraps of fabric from his mother’s sewing box, arranging them by texture, by cling. He delivered it like a cute anecdote. But the way he described nylon’s static crackle, velvet stuck to sweaty palms, the suffocating heat of polyester on bare skin—too much detail. Stomach advanced toward her oesophagus.

“You’re a strange one,” she said at last. A playful tone, the sort of banter one throws across a bar without thought.

But he heard only: You’re seen. He shifted his Omega watch higher on his wrist. “Strange is memorable.”

Her laugh broke against the mirrors, multiplying.

Later that evening, someone spilled a drink. The liquid spread across the counter in branching veins. She dabbed at her skirt with a napkin. He watched the fabric darken, clinging to her thigh. The cold must have sunk straight through, wet cloth plastering itself to stocking and then skin. He thought about keeping the napkin, still damp, holding the faint print of her leg. He thought about keeping all of them. A collection. A history.

It wasn’t a date. Or it was. Neither called it such. She agreed because—why not? She liked to test herself against people like him. Men too sure of their own charm. She liked the thought of a free dinner, not because she couldn’t afford it herself but because it was riddled with expectation.

They chose an Italian restaurant, all candlelight and brick walls. The kind of place people picked to seem ‘authentic’. He sat opposite. Posture rigid, eyes darting. He studied the way she cut her food: knife slicing with precision, fork balanced delicately. He timed his bites to hers, though she didn’t notice.

He watched her take glances at the man at the table beside them, her face blushing slightly. He had become a cuck on his own date. He wasn’t listening to her words anymore, only the mechanics of her eating: jaw opening, tongue darting, teeth sinking into the soft, wet pulp, grinding and pressing until it yielded, each bite slick with saliva, each click a reminder of the messy world inside her mouth.

He pictured the half-chewed bread inside her mouth, pulp dissolving with saliva. He thought of her body as porous, dissolving, leaking: the reminder that borders between inside and outside were never clean. He felt himself drawn to the horror of it.

Moeko Nakamura, Untitled, 2022. Digital photograph.

“You watch people very closely,” she said suddenly, breaking his trance. “Occupational hazard,” he replied. Far too quickly. “I deal with details.”

Silence followed. The waiter poured more wine. She reached for her glass. He imagined the taste of salt on her wrist, the slick between her fingers. He imagined the body as a wet surface to be entered.

As the evening wound down, she looked at him more steadily. She wasn’t sure if she was intrigued or repelled. Maybe both. He paid the bill without asking, eager. Walking her out, he brushed close, not touching, but near enough. She caught a glimpse of his hand twitching at his side, as though itching for something to hold. He flexed his bicep through his shirt deliberately, a silent performance of strength. She noticed.

He noticed her noticing. And in the split second before the night ended, he imagined her mouth open around the same bread he had torn, imagined crumbs dissolving in saliva, imagined the line between what was his and what was hers erased entirely.

He spotted her at the end of the train line. Black stiletto boots, a grey pencil skirt split neatly at the back.

She shifted her weight, one foot circling slightly on its heel. She hoped the slit wasn’t riding up too high, but didn’t check.

The train arrived with a rush of warm air, carrying the faint scent of oil and iron. She stepped inside, selected a seat without calculation, two rows from the door, back against the wall. Safe.

From a few seats away, he watched. He could see the lacy edge of her panty line. He imagined what it would look like on the floor. Her white button-up clung to her skin, tugging at the edges. He could make out the red strap of her bra through the thin white cotton. He wondered if it matched her underwear. Her glasses. Red, sleek, thin-framed. On one arm a smart handbag, on the other a purple knit jumper. He told himself he was only noticing, only attentive, but his noticing spread, growing sticky. The lace trim faintly visible through the skirt, the curve of her waist dipping, then spilling outward.

He touched the seam of his work trousers, drawing his finger down, retracing the line he imagined of her body. Again, and again. He thought about fabric—ninety percent cotton, ten percent polyester—and how polyester held heat, how it trapped sweat. He pressed harder, until the warmth beneath his fingertip felt like friction, as if her body might appear from it.

She crossed her legs. Maybe the shoes pinched at the ball of her foot. Or maybe, and here the thought unspooled too easily, she was clenching in. He pictured kneeling, sliding the boots from her feet, peeling down tights taut from static, placing her legs over his shoulders. She shifted again. He watched her mouth set in concentration, eyes lowered to her phone. Her thumbs worked quickly. Detached, efficient. He wondered who she was writing to. He imagined her fingers pressing into him instead, gripping his wrists hard enough to leave marks. He pictured himself slipping off his Omega watch, placing it neatly on the nightstand before climbing over her.

Her hair fell forward when the train halted. He saw sweat clinging to her forehead, strands pasted against her temples. He could hear it. He could smell it. The air in the carriage seemed suddenly thick. She looked up once, briefly, across the aisle. For half a second, her gaze might have swept over him. Or not. It didn’t matter. He felt the charge of it anyway, invented and then seized as truth. The train rocked on. To anyone else, she was absorbed, absent. To him, she was speaking already, her body full of sentences only he could read.

He wondered if she was thinking the same.

She wasn’t.

And still he imagined. He kept imagining because the imagining had already replaced her. She was no longer a woman on a train, she was the outline traced on his thigh, the red of a bra strap, the edge of lace, polyester holding heat.

The train lurched forward. She sat in silence. She sat untouched.

But in his head, she was already undone.

i bare it all yet still they do not see

My textile installation work i bare it all yet still they do not see (2025) interrogates the paradoxical relationship between the commodification of female bodies and convenience culture within contemporary capitalism. This is achieved through my engagement with slow craft where I construct representations of lumps of flesh from hand dyed, embroidered fabrics. Slow craft challenges obsession with productivity targets and overconsumption.

The work does not begin with the embroidering of the fabric but instead the preparation of a range of vegetables which are slowly processed into homemade fabric dyes. I am methodical in my preparation of the produce: peeling, cutting and boiling. The fabric is then scoured to remove any oils or waxes that accumulated during the manufacturing process. The fabrics are then immersed in the dye, dried, and cut into smaller portions. Delicate stitching is embroidered by hand onto each piece. These are sewn together into individual bags and suspended on meat hooks. The work does not end here, it continues to grow, actualised by the repetition of these processes over and over again. My work embraces the mistakes and experimentation with materials and processes that one undergoes when creating something by hand thus acting as a direct challenge of capitalist obsessions with productivity and perfection.

This slow process of artmaking acts as resistance to the culture of instant gratification and convenience that manifests in sex and relationships. With the rise of porn and the exploitation within the industry, the sacred aspect of sex has been overlooked and sex has transformed into a transactional phenomenon. Women often become nameless conquests, as though they are pieces in a butcher, ready to be portioned for sale. I meticulously craft these sacs of ‘infected flesh’ to represent this commodification. The work is paradoxical in that hours of dyeing, embroidering, and stitching in order to represent capitalist ideals of convenience, commodification, and instant gratification.

Eloise Tilbury

all yet they still do not see

By Samadhi Kumarage

The street is alive with horns and heat, the wind restless with shouts. Short-tempered drivers an d tourists with mopeds fashion a chorus of urgency. My father, ever unperturbed, sees a street vendor selling mangoes and pulls over. He buys a whole crate. I watch, eyes wide as he takes a bite from the most yellow-looking one, his teeth piercing the waxy skin. Golden juice glistens down his hand, his fingers covered in the fruit’s flesh. A smile washes over his face. “This is the only way to eat a mango,” he says, in between bites. I grin.

Breathless, I climb. The marble steps rise endlessly before us, I sigh with each footfall. A flash of fur catches me off guard. I scream. Demons. No, worse. Monkeys. I run down the steps and hide behind my mothers legs. She laughs, her voice steadier than the stone, “it was their home before ours.” My fear softens, though I feel the gaze of the monkeys linger, “we must learn to live together, not apart,” she says.

The smell of incense floods my senses as I enter the temple and suddenly all is fleeting. I carry a handful of white jasmine flowers from our garden, my small hands like oysters, protecting the petals as if they were pearls. I place the flowers gently in a porcelain bowl filled with water. I watch them swim in small currents, a tiny pool of stars floating before my palms. It is almost divine, I think, though I have not learned that word yet. Only the sense of something vast, something infinite, seeping into my bones.

I grip my mother’s hand tightly, not wanting to let go. We watch the other children from a distance, laughing in an unfamiliar language. I have no hat today, so the sun is forbidden. That rule seems strange to me. At home, I would play until my already brown skin deepened beneath the heat. My mother gives me a supportive nudge. But I hesitate. When I try to speak, my tongue feels sliced in two. One half desperate, reaching but still slips. The other half lingers, content to remain in its oblivion, because at least it was its own.

Cross-legged on a cushion, I listen. The chant rises and falls, words I once knew drifting past, leaving behind only rhythm. Low. Dissonant. The sound carries me. Outside, I see no monkeys. But white birds with curved beaks and yellow crowns gather. They seem to understand. Head-bowed, a small white string is tied around my wrist. Soon, it will decay.

The trolley rattles as I push it beneath the white tepid lights of the supermarket. Memories, like waves, sometimes pull me under. Other times I wade, waist-high, unsure if I am dreaming or if I am remembering. I reach the fruit aisle. There is an employee, his green fitted shirt half tucked in, restocking the mangoes. He notices me and smiles with crooked teeth, “would you like some? They are in season. Only $3.90 each!”