Collingwood Regeneration

I acknowledge the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung as the Traditional Owners of the land this project is located on.

I acknowledge the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung as the Traditional Owners of the land this project is located on.

What is the role of urban open space in 2050? How can design create vibrant social and ecological life in high density neighbourhoods? Can Melbourne be a city of villages?

By 2050 Melbourne’s urban population has almost doubled1, there will be more extreme weather events, loss of biodiversity and more climate change refugees. There will be an increased reliance on public open space and importance of designing high density, walkable communities that are sustainable and connected to nature.

Recently, major award winning architecture projects focused on social housing renewal, such as Lacaton and Vassal’s transformation of social housing in Bordeaux2, have brought into the spotlight the potential of post-war high rise housing buildings and their surrounding sites.

There are approximately 28 social housing sites across inner Melbourne, generally having the most height and open space in their urban areas. However, there are many problems with the architecture and urban design of these precincts, and the exploration and execution of solutions in Melbourne is very limited.

The research and design solutions discovered in this thesis have the potential to be applied not only to the social housing estate in Collingwood, but the various social housing sites across Melbourne that won’t be liveable or sustainable in 2050.

1 Victoria State Government. (2017). Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 Summary. https://www.planmelbourne.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_ file/0009/377127/Plan_Melbourne_2017-2050_Summary.pdf

2 The Pritzker Architecture Prize. (2021). Anne Lacaton and Jean Philippe Vassal. https://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/anne-lacaton-andjean-philippe-vassal

Figure 01. Adelaide Botanic Gardens Wetland. Gollings, J. (2015). Adelaide Botanic Gardens Wetland. TCL. https://tcl.net.au/projects/adelaide-botanic-gardenswetland

To address the disruptions faced by the climate emergency and growing urban population in 2050, we will need a holistic design approach that focuses on nature and biodiversity, climatic conditions, climate emergency adaptation and mitigation processes as well as community health and wellbeing1.

“We need a mind shift to reconnect world development with planet earth.”2

With nature at the centre of design decisions, it will be valuable to turn to indigenous design perspectives. Most architecture students are first introduced to design with the principles of the Bauhaus, such as point, line and plane, but in order to design for life beyond the anthropocene, architectural approaches can instead embrace indigenous design principles.

Designing with Country shifts away from a human-centred design approach to Country-centred design which views all natural systems including people, animals, resources, and plants, as equally important parts of a connected ecosystem3.

1 Nikologianni, A., & Larkham, N. (2022). The Urban Future: Relating Garden City Ideas to the Climate Emergency. Land 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/11/2/147/htm

2 Rockström, R. (2017). Beyond the Anthropocene. World Economic Forum. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=V9ETiSaxyfk

3 Government Architect New South Wales. (2020). Designing with Country. https://cdn.sanity.io/ files/64znbptb/production/195dcdd4c5ceeb13fdc16055ce22a1342c608aca.pdf

Figure 02. Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse concept. Le Corbusier. (1925). Ville Radieuse. A contemporary city. https://thecharnelhouse.org/2014/06/03/lecorbusierscontemporary-city-1925/le-corbusier/.

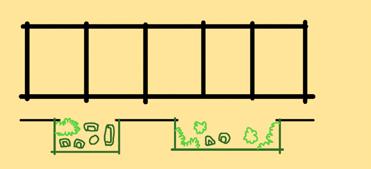

The high rise social housing buildings in Melbourne are the legacy of a Modernist idea. Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse1 concepts suggested single use buildings, separation of class, and expansive space between buildings.

The problems with this design approach is the neglect of the human scale, removing people from the street and hindering community vibrancy.

“If anybody wanted to pay professionals to make a city planning idea which would kill city life, it could not have been done better than what the modernists accomplished.”2

The opportunity created by this design approach in Melbourne, however, is the large amount of open space that the high rise social housing buildings sit on.

The Collingwood social housing estate is the largest open space resource in a one kilometer radius (see figure 10), giving it potential to operate as the green lungs of the surrounding suburb.

1 Merin, G. AD Classics: Ville Radieuse / Le Corbusier. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/411878/ad-classics-ville-radieuse-le-corbusier

2 The Human Scale, directed by Andreas M. Dalsgaard (Denmark: Madman Entertainment, 2012), https://unimelb.kanopy.com/video/human-scale.

Figure 03. One Central Park by Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Dig It Photography. (2019). The Best Tall Buildings of 2019, According to the CTBUH. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/914913/the-best-tall-buildings-of-2019-according-to-the-ctbuh?ad_medium=gallery

As Melbourne’s urban areas densify in 2050, there will be more pressure public open space. A loss of open space will mean a loss of biodiversity and the green space that helps cool the city.

More attention will need to be given to the amount, size and location of public open space, as only half of Melbourne residents currently have access to public open spaces larger than 1.5 hectares1.

Urban green space is not only beneficial in addressing the effects of climate change, but it can promote widespread improvements to mental and physical health, and reduce rates of death and disease2.

A 21st century interpretation of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concepts3 can offer design tools for 2050 with a greater integration between urban areas and green spaces.

“Since the industrial revolution, our society has focused on mass production. Now is the time to shift towards mass greening”.4

1 RMIT University. (2018). Creating liveable cities in Australia. https://cur.org.au/cms/wp-content/ uploads/2018/09/melbourne-city-score-cards.pdf

2 World Health Organisation. (2017). Urban Green Space Interventions and Health. https://www. euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2017/urban-greenspace-interventions-and-health-a-review-of-impacts-and-effectiveness.-full-report-2017

3 Ebenezer, H. (1902). Garden Cities of Tomorrow. Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd.

4 Takada, K. (2020). Koichi Takada Unveils World’s Most Dense Vertical Gardens. Koichi Takada. https://koichitakada.com/news/hello-world/

Figure 04. One Central Park by Ateliers Jean

Frendericks, M. (2014). One Central Park / Ateliers Jean

. ArhDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/551329/onecentral-park-jean-nouvel-patrick-blanc?ad_medium=gallery

Nouvel. NouvelLandscape and built form are often perceived as separate elements of a city but in a high density neighbourhood vertical greening systems designed to incorporate nature can improve biodiversity and a connection to nature.

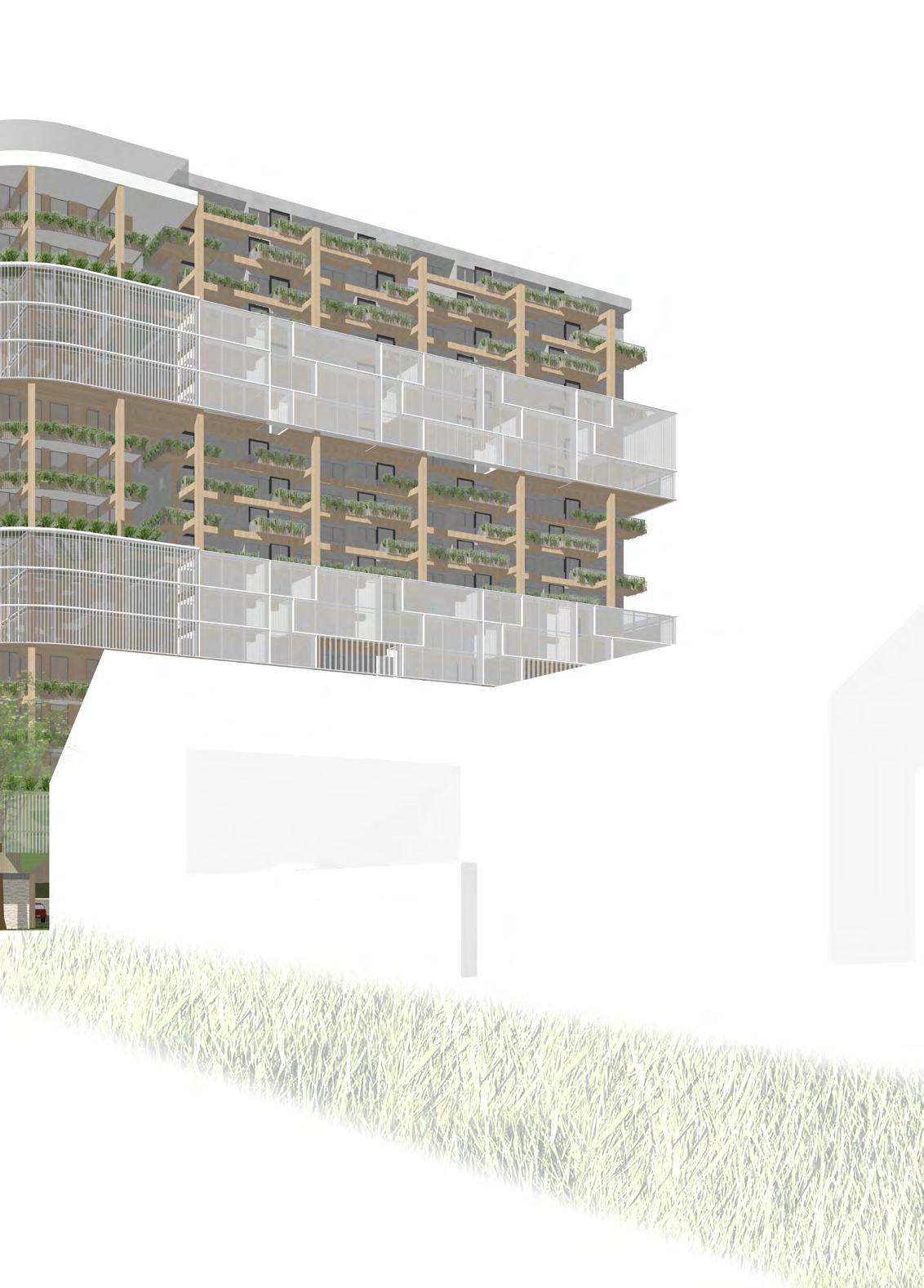

As Melbourne becomes a more dense and populated city, green roofs, walls and facades can help support greening where space is tight1. Vertical planting in high-rise buildings allows architecture to bring greenery, biodiversity, oxygen and mental health benefits back to high-density city living2.

The One Central Park project in Sydney is covered approximately 50% in landscape. The adjacent urban park landscape extends vertically onto the building creating a living environment in harmony with nature and a powerful green icon on the Sydney skyline3.

1 City of Melbourne. (2022). Green infrastructure. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/ greening-the-city/green-infrastructure/Pages/green-infrastructure.aspx

2 Takada, K. (2020). Koichi Takada Unveils World’s Most Dense Vertical Gardens. Koichi Takada. https://koichitakada.com/news/hello-world/

3 Ateliers Jean Nouvel. (2014). One Central Park. http://www.jeannouvel.com/en/projects/onecentral-park/

https://juddyroller.com.au/project/wellington-st-high-rise/

Figure 05. Matt Adnate’s mural on the Wellington Street high rise. Reed, N. (2018). Wellington St High Rise. Judy Roller.By 2050, an estimated 1.2 billion people will be at risk of displacement1 from countries that don’t have the resilience to deal with ecological changes.

Social housing is an important part of Melbourne’s urban fabric as the first homes for many refugee arrivals in Melbourne. There is currently a lot of stress on public housing with waiting lists growing by 500 people a month2 and that pressure is likely to continue with an increasing number of climate change refugees.

The Modernist approach to the design of the high rise social housing is a contributing factor in the resulting social stigmas and associations with crime, social isolation and urban blight3.

Projects to recitfy some of these issues have begun across Melbourne by filling in the surrouding precinct with private high rise housing. However, research argues that the design of projects such as the Carlton Public Housing estate, particularly the separation of public and private housing, has lead to poor social inclusion4. The resultant design involved three buildings that do not interact with each other and a physical barrier between the public spaces available to residents of public and private dwellings.

This thesis project aims to find design solutions that revitalise the buildings while supporting diverse and inclusive communities. Matt Adnate’s mural on the project site illustrates a first step in celebrating the diversity of the people in this community and bringing some character and life to their home.

1 Institute for Economics and Peace. (2020). Ecological Threat Register. https://www. economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ETR_2020_web-1.pdf

2 Tran, D., & Stayner, G. (2018). Victorian public housing waiting list at 82,000 and growing by 500 a month. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-06/victorias-public-housing-waiting-list-growingby-500-a-week/9837934

3 Faleh, M., Cook, A.,Haw, A., & Carrasco, S. (2019). Paris? Melbourne? Public housing doesn’t just look the same, it’s part of the challenges refugees face. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/parismelbourne-public-housing-doesnt-just-look-the-same-its-part-of-the-challenges-refugees-face-110284

4 Levin, I., Arthurson, K., & Ziersch, A. (2014). Social mix and the role of design: Competing interests in the Carlton Public Housing Estate Redevelopment, Melbourne. Cities. https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/abs/pii/S0264275114000481?via%3Dihub

Figure 06. Lacaton & Vassal’s transformation of social housing in Bordeaux. Ruault, P. (2016). Transformation of 530 dwellings. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/915431/transformation-of530-dwellings-lacaton-and-vassal-plus-frederic-druot-plus-christophe-hutin-architecture?ad_medium=gallery

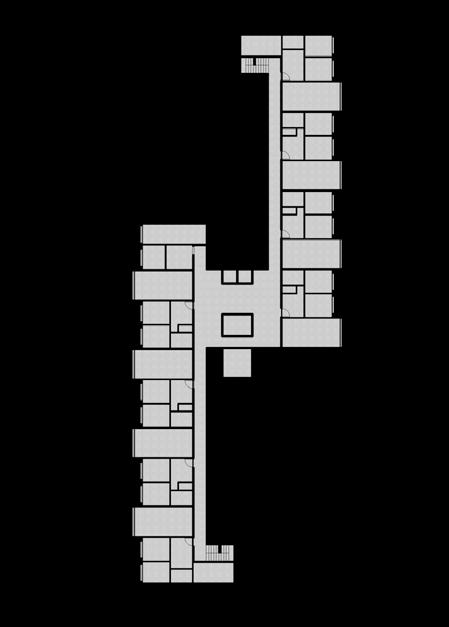

This design thesis will focus on a sustainable approach to turning this precinct into a desirable place to live, by considering what existing building infrastructure can be rethought instead of demolished.

Recently, major award winning architecture projects focused on social housing renewal, such as Lacaton and Vassal’s transformation of social housing in Bordeaux1, have brought into the spotlight the potential of postwar high rise housing buildings and their surrounding sites.

Lacaton and Vassall’s transformation of social housing in Bordeaux focuses on transformation instead of demolishing and rebuilding. Their approach aims to give value to the existing before making changes, improve the performance and sustainability, and extend the life of the building.

Prefabricated modules are attached to the building’s facade to create new semi-outdoor spaces that are left unprogrammed to allow for creativity, personalisation and adaptation by the residents2.

‘Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform, and reuse!’3

1 The Pritzker Architecture Prize. (2021). Anne Lacaton and Jean Philippe Vassal. https://www. pritzkerprize.com/laureates/anne-lacaton-and-jean-philippe-vassal

2 Lacaton, A., & Vassal, J. P. (2016). Transformation of 530 dwellings. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/915431/transformation-of-530-dwellings-lacaton-and-vassal-plus-frederic-druot-pluschristophe-hutin-architecture?ad_medium=gallery

3 Art Review. (2021). Pritzker Prize awarded to social housing duo Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. https://artreview.com/pritzker-prize-awarded-to-social-housing-duo-anne-lacaton-and-jeanphilippe-vassal/#:~:text=The%20French%20architects%20have%20adopted,’&text=The%20prestigious%20 Pritzker%20Prize%20has,Lacaton%20and%20Jean%2DPhilippe%20vassal.

Figure 07. Wellington Street social housing tower. Author’s photograph.

Figure 07. Wellington Street social housing tower. Author’s photograph.

This design thesis aims to rethink, not just adapt to, the disruptions 2050 will bring. It will explore the ways architecture and urban design can equally benefit the environment and the community and challenge the design approach, to make an impact at a larger scale.

“Think globally, act locally”

It will imagine Melbourne as a city of villages, composed of precincts that are dense, mixed use, pedestrianised and connected to nature and community.

There are approximately 28 high rise social housing sites across inner Melbourne, generally having the most height and open space in their urban areas.

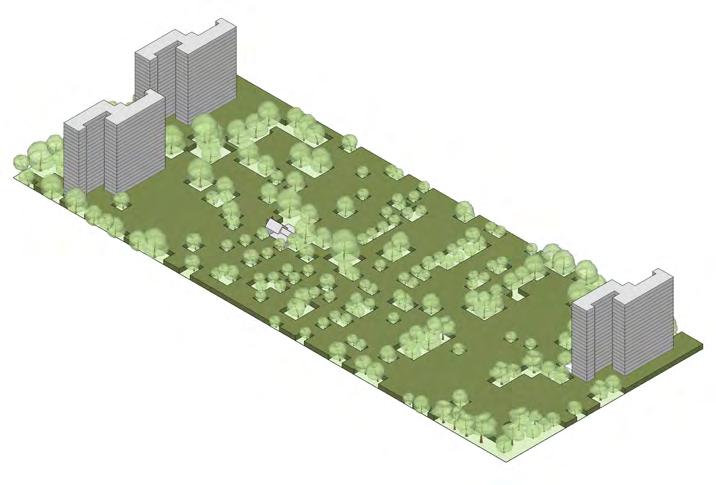

The Collingwood social housing precinct contains three high rise housing towers surrounded by open space and low density walk-up flats. The focus will be on regenerating the precinct to perform as the green lungs of the suburb and transform the unliveable to the liveable and alive.

The site is located in Collingwood, approximately 2km northeast of Melbourne’s CBD. This site was studied across the studio, with students each selecting a site of interest to them. As my interest lies in urban design I chose to study the site as a whole and design a masterplan for the precinct alongside a detailed design of one of the tower renovations.

I am quite familiar with this site as I used to work in the area, so I am familiar with the social stigma that surrounds the public housing properties. Despite walking past this site many times, there was a physical and mental barrier that caused me to never enter it. The perimeter fence creates a physical separation and feels unwelcoming to the community. This project aims to break down these barriers and create a diverse, lively and welcoming precinct.

Mapping the social housing estates aross North East Melbourne reveals that they are significant pieces of open space in their surrounding suburbs.

Mapping these open spaces as the lungs of an 800m walkable village reveals that Melbourne can be composed of a series of villages, each with their own character and identity, anchored by the lungs. The lungs can act as a place of refuge and connection to people and nature.

Mapping this site in its context shows that this precinct will be the largest open space within an 800m radius. It is approximately double the other significant open space, Victoria Park. The City of Yarra has identified Collingwood as one of the area’s most open-space deprived suburbs, at only 0.3 per cent open space, compared with the municipal average of 13.5 per cent.1

There is an opportunity for the site to connect to other green spaces with a network fo green corridors. This will act as the green veins of the village, breating life into the urban area, as well as allow biodiversity to travel from one green space to the next.

There is some significant native vegetation on site. Mature gum trees are indicated at the north west and south east of the site and these must be retained and protected in the design.

1 Waters, C. (2021). Green spaces, rollerdisco to go in plan for new homes on public estate. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/national/ victoria/green-spaces-roller-disco-to-go-in-plan-fornew-homes-on-public-estate-20211206-p59f3t.html

This map indicates a range of amenitites that make Collingwood a unique and lively place.

To the east of the site is a creative education precinct with the Collingwood Yards, Melbourne Polytechnic and Collarts. The Bendigo Hotel and the Tote are pubs that feature live music and create activation over evening hours which can be drawn on in this precinct to bring life and safety to the site over more hours. The site is bordered on the west and south by two schools, making the interaction with education an opportunity to explore.

There are also a few amenities within the site including the Harmsworth Community Hall which is located in a historic church, the underground carpark that is used as an event space, and the neighbourhood house that offers resources and surrport for residents.

To the east of the site Collingwood Station and Victoria Park Station can be reached in a short walk, and busses frequent Hoddle Street, making public transport easily accessible for residents. There is also a hgih quality bike lane on Wellington Street encouraging active transport.

This site is also home to a historic small Gothic Revival church built in 1876. Today it is home to Operation Stitches which is a community development charity that fosters community connection and improve the life outcomes for disadvantaged inner-city communities.

The Collingwood Neighbourhood House is located on the Collingwood Housing Estate.

The house offers a range of social, recreational and educational activities and programs that meet the needs of the diverse multi-cultural community.

Collingwood Neighbourhood House provides a friendly environment for the community to meet and create friendships.

Figure 08. Pocket Oz. (2020). Collingwood’s Architectural History. https://pocketozmelbourne. com.au/collingwood-architecture.html

Figure 09. Collingwood Neighbourhood House. (2021). Facebook. https://www.facebook. com/collingwoodneighbourhoodhouse/ photos/4720307984693932

The 200 space carpark underneath the eastern towers is used for events such as roller-discos, exhibitions, concerts and Victoria’s only black and queer-centred gym. Roller-disco founder and public housing resident Joshua Tavares said the underground car park was significant as the only resident-led “black space” on the estate.1

EXTEND THE UNDERGROUND

REVEAL PARTS

CONNECT WITH A NATURAL AMPHITHEATRE

SIGNIFICANT TREE COVERAGE ACROSS THE SITE

1 Waters, C. (2021). Green spaces, rollerdisco to go in plan for new homes on public estate. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/national/ victoria/green-spaces-roller-disco-to-go-in-planfor-new-homes-on-public-estate-20211206p59f3t.html

Figure 10. Beat. (2019). Collingwood Underground Roller Disco is wrapping up its summer season https://beat.com.au/mount-beauty-musicfestival-is-bringing-music-arts-and-culture-toregional-vic/

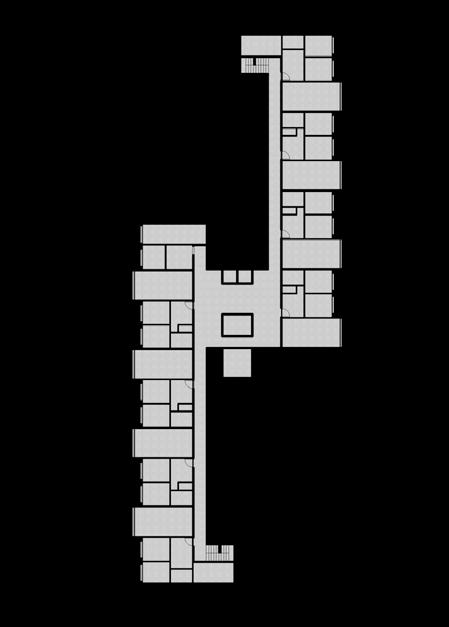

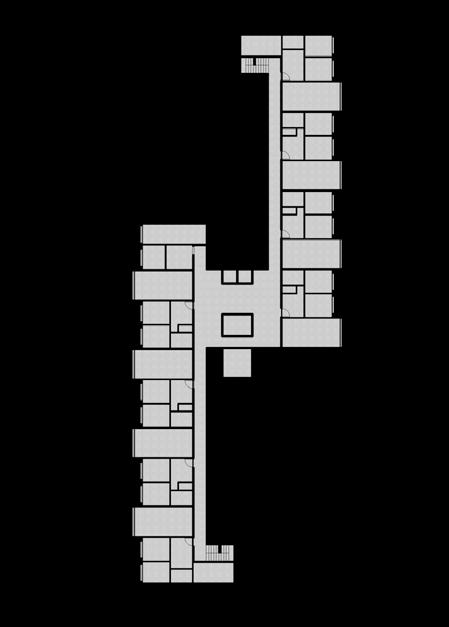

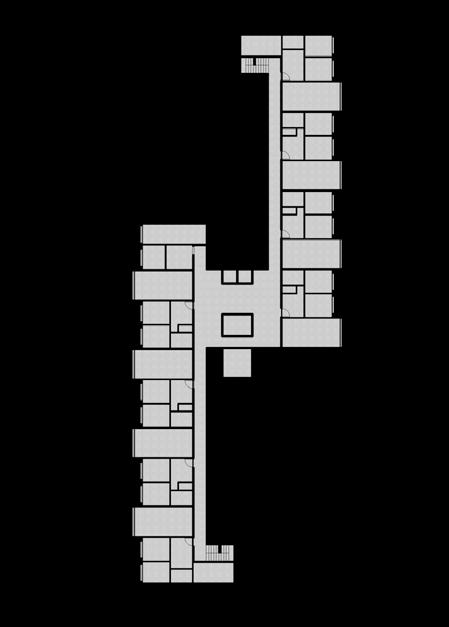

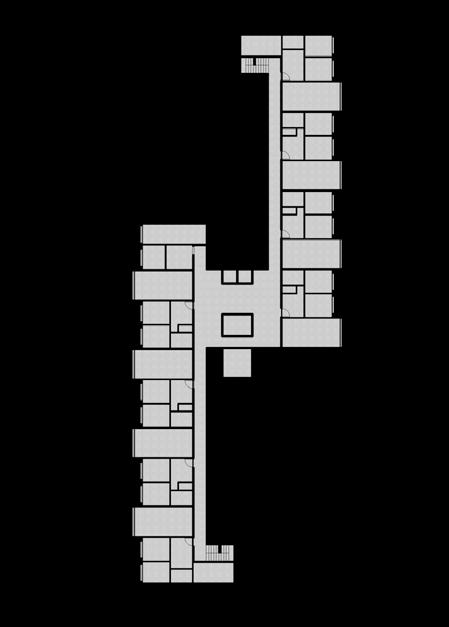

The site is currently a purely residential precinct, with a variety of low density social housing, and 3 high rise public housing towers.

A density analysis was conducted to determine the current capacity of the site and will be used to investigate options in increasing the residential density.

Assume:

Walk-ups = 2 bedrooms

Townhouses = 3 bedrooms

Duplex = 2 bedrooms

273 walk-up flats = 546 bedrooms

66 townhouses = 198 bedrooms

6 duplex = 12 bedrooms

660 apartments = 1140 bedrooms

TOTAL DWELLINGS = 1105

TOTAL BEDROOMS = 1896

WALK-UP FLATS

LACATON & VASSAL, 2016, FRANCE

A well known case study, this project transformed 3 modernist social housing buidings. The project was completed while residents remained in their apartments. The project of transformation focused on improving hte quality of the existing apartments, and adding winter gardens and balconies to extend residents private living space. This project however does not have the added complication of load bearing exterior walls.

Figure 12. Ruault, P. (2016). Transformation of 530 dwellings. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/915431/transformation-of-530-dwellingslacaton-and-vassal-plus-frederic-druot-pluschristophe-hutin-architecture

TEGNESTUEN LOKAL, 2020, DENMARK

This project is a facade extension of a modernist housing building and inspired my thinking about opportunities for semi-private spaces and how they can play a role in encouraging social interaction. The visual and social environment is improved for residents and visitors with the addition of triangular glass bays that create semi-private decks. The decks are placed on the outside of the walkway to encourage more interaction between residents.

Figure 11. Berndtson, H. (2020). Ørsted Gardens Apartments / Tegnestuen LOKAL. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/948801/orstedgardens-apartments-tegnestuen-lokal

ADDITIONAL STRUCTURE

INCREASE DENSITY OF HIGH RISE TOWERS BY ADDING APARTMENTS AND EXPANDING APARTMENTS TO INCLUDE LARGER FAMILIES

RETAIN PILOTIS TO ALLOW GREENING UNDERNEATH FRONT YARDS

SELF-SUPPORTING STRUCTURE RATHER THAN HANGING OFF THE PREFAB PANELS

SIMPLE FRAME AND MODULAR COMPONENTS

The future vision of our city in 2050 overlays all design thinking and decisions in this thesis project. This involves imagining what our world might look in various scales, from global impacts to our cities and suburbs, and down to our home and social environments.

Design will need to respond to new challenges and disruptions, technological and industrial developments and the impacts of climate change.

Disruption is simply ‘change that has not been planned for’... this studio will seek look ahead of the curve and investigate scenarios for what life and the profession may look like in 2050.1

1 Barnett, C. (2022). Disruption. Melbourne School of Design. https://msd.unimelb.edu.au/current-students/subject-information/msdstudios/master-of-architecture-design-thesis/THE-2022_SM1-Studios/ studio-11

In 2050 Melbourne will experience an average of 16 days greater than 35 degrees compared to 11 currently and temperature increases mean we could lose 35 per cent of the city’s trees in the next 20 years.1 Most homes and buildings currently operate with air conditioning units that are energy intensive so by 2050 we will need to move to natural cooling and ventilation solutions.

1 City of Melbourne (2022). Climate change impacts on Melbourne. https://www. melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-council/visiongoals/eco-city/Pages/adapting-to-climatechange.aspx

Figure 13. Breathe. (2014). The Commons https://www.breathe.com.au/project/thecommons

Melbourne will experience more severe rainfall events, increasing the likelihood of flooding and storm surge. By 2050 sea levels will rise by 24 cm on 1990s levels.1 Collingwood has a history of flooding, so integrating levees and floodable spaces into the public realm will be important.

1 City of Melbourne (2022). Climate change impacts on Melbourne. https://www. melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-council/visiongoals/eco-city/Pages/adapting-to-climatechange.aspx

Figure 14. Sotnikov, M. (2008). The Cheonggyecheon River. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/931720/how-cities-are-usingarchitecture-to-combat-flooding

Climate change and urbanisation is disrupting natural cycles and habitas. Urbanization is expected to reach 68% by 20501 meaning more natural land and habitats will be removed. Cities become essential in sustaining biodiversity, with some species having higher populations in cities than rural areas. Buildings can provide habitats for multiple species and prefabricated components can reduce disturbance on site.

1 United Nations. (2018). 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ en/news/population/2018-revision-of-worldurbanization-prospects.html

Figure 15. Sim, Q. (2020). Singapore Pavilion ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/974707/ biodiversity-in-urban-environments/61d756 79336e287345745464-biodiversity-in-urbanenvironments-photo

By 2050, up to 300 million people around the world will have been displaced by impacts of climate change1. It is likely that an increased number of migrants will arrive in Australia from the Indo-Pacific region which will be most affected by climate change, with inhabitants of low-lying islands in the Pacific among the most vulnerable.

1 Hawkins, R. (2020). Stepping up to Australia’s Climate-Refugee Conundrum. Asialink. https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/asialinkdialogues-and-applied-research/emergingvoices/stepping-up-to-australias-climaterefugee-conundrum

Figure 16. Chameleonseye. (2020). Australia should create ‘Pacific visa’. The Guardian. https:// www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/21/ australia-should-create-pacific-visa-to-reduceimpact-of-climate-change-and-disaster-onislanders

By 2050 it is likely that autonomous vehicles will become the norm and car parks will almost be obsolete.1 The energy to power vehicles will transition from oil to electric. Designing high density sustainable neighbourhoods will put an increased emphasis on active and public transport and be less car dependant.

It is projected that 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050.1 With our cities getting denser it will be important to design high quality public open spaces and integrate a connection to open space in all buildings. As cities continue to grow so will the urban heat island effect as vegetation is lost and surfaces are paved or covered with buildings, so cooling the city through greening projects will also be important.

1 Dawson, R. (2021). What we do now that will be unfathomable by 2050. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/ lifestyle/life-and-relationships/what-we-do-nowthat-will-be-unfathomable-by-2050-20210806p58ghy.html

Figure 17. Author’s photograph

1 United Nations. (2018). News. https:// www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/ population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanizationprospects.html

Figure 18. The Conversation. (2020). Theres no need to give up on crowded cities. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-19/ crowded-cities-we-can-make-density-so-muchbetter/11976458

The future of sustainable construction methods is heading towards mass timber and prefabricated elements. Prefabrication can improve equality in the workforce by bringing workers into the warehouse. Prefabrication makes the construction process easier and faster, causing less disturbance to the site and allowing people to stay in place longer. There will also be an increased use of technologies such as BIM, 3D printing and autonomous design.

Figure 19. Naturally Wood. (2017). Inside Vancouver’s Brock Commons, the World’s Tallest Mass Timber Building. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/879625/inside-vancouvers-brockcommons-the-worlds-tallest-timber-structuredbuilding

1. Country Centered

2. Village Inspired

3. Socially and Functionally Diverse

As a green lung of the city, nature is the heart of the precinct. The design should respond to local context and value First Nations connection to Country. There is an opportunity to decolonise design and value Country as equal to people. The precinct should foster ecology and biodiversity as a key element of the village and respond to the environmental challenges of 2050.

Figure 20. Carson, A. (2008). Yarra River. Wikipedia. https://simple.wikipedia. org/wiki/Yarra_River

The Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung are the Traditional Owners of the land this project is located on. The Wurundjeri people used to call the area between Fitzroy and Collingwood: ‘Yálla-birrang’, which means ‘The wooden point of a reed spear’1.

This area has been an important meeting place for First Nations people since the 1920s.By the 1950s it was a social and political hub and home to the largest Aboriginal community in Victoria. It is the birthplace of many Aboriginal organisations and a meeting place for Aboriginal people to connect with family, community and services.

The connection to waterways is very important to First Nations culture. This site sits close to the Birrarung (Yarra River) which was historically a fishing and eeling site and a place to camp for long periods.2

The locality at the junction of the Merri Creek and the Yarra River is of particular importance as a favourite gathering place and camping place of the Wurundjerri people. The flat land is very prone to flooding, and historically was a swampy plain. In winter, the Wurundjeri-willam regularly camped in the higher areas as the land near the river flooded.3

To start thinking about decolonising the design approach and designing for Country we can look at some indigenous design principles to find a new way of looking at, respecting and celebrating the site.

• Hierarchy of places of significance

• Promote biodiversity

• Orientation & solar control

• Promote culture

• Connect people to Country

• Let Country be

• Topography

• View points4

“It’s all about care and responsibility”5

- Bruce Pascoe

1 Valdinoci, F. (2019). Mural honours suburb’s Aboriginal heritage and history. SBS. https://www.sbs. com.au/language/english/melbourne-mural-honours-suburb-s-aboriginal-heritage-and-history

2 Yarra City Council. (2013). Aboriginal History of the Yarra. Agora vol. 48, no. 4. https:// aboriginalhistoryofyarra.com.au/

3 Yarra City Council. (2013). Aboriginal History of the Yarra. Agora vol. 48, no. 4. https:// aboriginalhistoryofyarra.com.au/

4 Hromek, M. (2020). Aboriginal Design Principles. WSP. https://shared-drupal-s3fs.s3-apsoutheast-2.amazonaws.com/master-test/fapub_pdf/000-Wagga/Aboriginal+Design+Principles.pdf

5 ABC. (2022). Bruce Pascoe’s farm and design after disaster. Blueprint for Living. https://www.abc. net.au/radionational/programs/blueprintforliving/blueprint/13870152

Camps and gathering places along a blue corridor.

Design for river flooding and storm water capture.

Mounding for higher ground retreat during flooding and place to watch over the land.

MOUNDING TO RETREAT FROM FLOODING AND WATCH OVER SITE

Intersection of paths mirroring the significant Yarra and Merri Creek intersection.

MOUNDING ALSO BUFFERS NOISE OF HODDLE STREET RIVER

TOTAL SITE GREEN COVEREAGE

VERTICAL GREENING OVER THE EXISTING TOWERS

CENTRAL CIRCULATION TO CREATE COMMUNAL SPACE

CLIMBING OVER BUILT FORM

BUILT FORM ON STILTS

GROUND PLANE RETAINED FOR BIODIVERSITY?

CIRCULATION

SUNKEN GARDENS & THE UNDERGROUND

PLATFORM

TREE TOP LIVING

BREAK BUILT FORM TO RETAIN EXISTING TREES

PILOTIS

UNDERGROUND

PEOPLE

ENVIRONMENT

This project inspired my thinking of the relationship between people, nature and water. This project is a regenerative living landscape, it is a constructed wetland that is used for ecological flood control and urban agriculture. There is something poetic in the design with the selection of crops and plants that allow people to witness seasonal changes. Nodes and paths interact with the landscape, creating enclosures for rest and gathering.

Mandy Nicholson is a local Wurundjeri, Dja Dja wurrung and Ngurai illum wurrung artist. Her artwork sweeps across the interior of the sawtooth roof. The concept is deeply embedded to Place, reflects Wurundjeri culture and references local landmarks. Wurundjeri are a carving culture and use many symmetrical lines and diamond motifs, and this is a great example of how local Aboriginal artists and culture can be celebrated in an urban context.

Figure 21. Turenscape. (2010). Shanghai Houtan Park / Turenscape. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/131747/shanghai-houtan-parkturenscape?ad_medium=gallery

Figure 22. Balarinji. (2019). Burwood Brickworks Public Art Installations. https://www.balarinji.com. au/burwood-brickworks

This is an interesting example of flood control aims to turn the waterway from a simple piece of infrastructure – used for logistics, sewage, and flood prevention – to a true public space for culture, life, and ecology. With an integrated approach that considers not only the canal, but also the public spaces around it and the routes alongside it, the proposal aims to transform the city by redesigning the canal.

Although in a more suburban context, this precedent is an interesting proposal for a mixture of public open spaces while managing the flood risk of a creek corridor. It will restore the creek with healthy ecosystems and habitats for flora and fauna, and acknowledge the strong Aboriginal connection to the site.

Figure 23. MVRDV. (2020). The Grand Blend. https://www.mvrdv.nl/projects/454/the-grandblend

Figure 24. McGregor Coxall. (2019). Moonee Ponds Creek Opportunities Plan. https:// mcgregorcoxall.com/project-detail/1131

To create a sense of community and social connection, the precinct will be inspired by the village. It will be pedestrianised and desiged for the human scale. A network of villages within the precint will allow the community to connect with their own place and express their unique identity and character.

Figure 25. Getty Images. What Would a “Green New Deal” Look Like for Architecture? Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/ story/green-new-deal-architecture

Figure 26. London Social & Functional Analysis Abercrombie, P., & Forshaw, J. (1944). We love designing in this city of villages. Assael. https://assael.co.uk/news/2012/ we-love-designing-in-this-city-of-villages/

Can we move forward in architecture and urban design by looking back to the historic walkable village? Future trends are heading away from the car dominated landscape, back to walkable precincts that strive for a tight-knit community with a strong sense of belonging. Architectecture that fosters community connection can boost health and happiness and equality for people of all ages, backgrounds, and living situations.

Villag design provides shared facilities and services that keep you close to what you need on a daily basis such as communal kitchens, daycare, urban gardening, fitness and groceries. High density urban villages can help mitigate the affects of climate change as they require less driving, shared resources and smaller homes that require less heating and cooling.

To improve liveability, we need to create a city of 20-minute neighbourhoods. The 20-minute neighbourhood concept is all about ‘living locally’—giving people the ability to meet most of their daily needs within a 20-minute return walk from home, with access to safe cycling and local transport options.1

London’s ‘villages’ contribute much to the city’s character, sense of place and performance as one of the global cities of the world.2 London’s unique village character was identified in a graphical map intended as a ‘social and functional analysis’ of London by Patrick Abercrombie and John Forshaw. The map is a simplification of the existing communities & open space and was intended to be used as a grand masterplan of how a post-World War II London could look.

“First life, then spaces, then buildingsthe other way around never works.”

― Jan Gehl, Cities for People

1 Victoria State Government. (2017). 20-minute neighbourhoods. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/ policy-and-strategy/planning-for-melbourne/plan-melbourne/20-minute-neighbourhoods

2 Assael. (2012). We love designing in this city of villages. https://assael.co.uk/news/2012/we-lovedesigning-in-this-city-of-villages/

The existing streets feel comfortable at the human scale. It is quite a pedestrian friendly precinct as there is not much vehicle movement through the site. The sound of birds is prominent in the tree-lined streets and it is connected well with parks and green spaces. The residents have added their personal touch of creativity around the precinct. Allowing this to continue helps residents feel ownership over the place. How can design foster creativity?

EXTENDED LIVING

3 LEVEL NEIGHBOURHOOD

BALCONY & ACTIVE STAIRS CONNECTING APARTMENTS

EXTENDED LIVING

CIRCULATION ATRIUMS

EXOSKELETON FRAME

OPEN UP CORRIDORS TO CREATE SHARED SPACES

NORTHERN SUN GARDENS NEW APARTMENTS

Thsi project was introduced to be during a critique session and really embodies the theories and ideas I have been thinking about in my research. It allows for individual creativity of residents and a chance for a neighbourhood to form vertically, bringing in the concept of the front yard and street life. It is an statement of anti-formalism where residents determine their own choices of residential style and uses of the real estate parcels. The only contribution by the architect is the construction of the support structure.

This project inspired me to think about how the essence of street life and a sense of community can be created in a high rise building. The tower is broken up into neighborhoods of 6 storeys, creating a mix of indoor and outdoor spaces and vertical connections between. The connecting spaces are naturally ventilated and large planted terraces give access to nature.

Figure 28. SITE. (1981). Highrise of Homes theoretical project. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/783491/interview-with-jameswines-the-point-is-to-attack-architecture

Figure 27. SHoP., & BVN. (2020). The World’s Tallest Hybrid Timber Tower is Under Construction in Sydney, Australia. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/942496/the-worlds-tallest-hybridtimber-tower-is-under-construction-in-sydneyaustralia

This project embodies all of the ideas of a village, in a sustainable and affordable solution. It is centered around improving the lives of residents, creating a liveable environment that suits the community’s unique needs, adapts to changes in daily life and offers support systems and social life. It explores interesting ideas about adaptable homes, and a variety of apartment types for all stages of life.

Figure 29. SPACE 10., & EFFEKT Architects. (2018). The Urban Village Project. https://www. urbanvillageproject.com/

The precinct will have a mix of uses that allow residents to live, work, play in their village, activate the precinct over more hours of the day and create a safe place that is thriving with activity. Residential density will be increased to offer more affordable and social housing, and the precinct will act as an incubator for new migrants, celebrating the rich range of cultures.

Figure 30. Alex Shots Buildings. (2019). Manifesto Market / CHYBIK + KRISTOF ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/934039/manifesto-market-chybikplus-kristof?ad_medium=gallery

By 2050 the low density housing will be outdated and will need to be replaced. They are mostly walk-up flats so are not equitable and there will be more possibility for density on the site.

The three towers have more embedded energy and architectural history than the low density housing. There is potential to transform the existing buildings by reskinning them to improving the living quality and add density to cater for a growing population.

“We are large families living in our crowded houses...there is a lot of people living seven or eight in two bedrooms” 1

1 Muhudin, F. (2021). Green spaces, roller-disco to go in plan for new homes on public estate. The Age.https://www.theage.com.au/ national/victoria/green-spaces-roller-disco-togo-in-plan-for-new-homes-on-public-estate20211206-p59f3t

RESIDENTIAL

This site is located in close proximity to tertiary education so there is an opportunity to introduce some affordable student accommodation which will also increase the social diversity.

To allow for aging in place and for multigenerational families to remain in close proximity, there is opportunity for some aged care which may be located near child care for wellbeing and social integration purposes.

Due to the overcrowding of the existing apartments with large family units, and the liklihood of increased large migrant families there is room for some large apartments to cater for multigenerational families

With the influx of new migrants and climate change refugees, might come a range of skils that can be showcased. Live / work housing can offer the opportunity for residents to celebrate and earn from their skills with a small retail, workshop or studio space below their house.

SMALL STUDIO / SHOP / GALLERY / OFFICE FOR EACH RESIDENT

Public housing is managed by the state government and rent is capped at 25% of your income. There is currently a shortage and a long waiting list so Victoria’s Public Housing Renewal Program aims to provide at least 1,800 new public housing dwellings, and grow the social housing stock in Victoria by at least 10 per cent. This will involve redeveloping old public housing stock, as well as the construction of new stock.1

Affordable housing meets the needs of very low and moderate income households. For Melbourne to continue as a livable city, there is an increasing urgency to provide affordable housing close to jobs, social networks and transport. This will achieve an equitable, functioning and productive city. There have been a variety of measures put forward by the government, private sector and institutions, but we still fall well below our targets for affordable housing.1

1 Infrastructure Pipeline. (2021). Victorian Public Housing Renewal Program. https:// infrastructurepipeline.org/project/publichousing-renewal-program

Figure 31. Onto It. (2022). Public Housing Renewal Program. https://ontoit.com/projects/publichousing-renewal-program/

1 NGV. (2019). How do we build the next generation of affordable housing? https://www. ngv.vic.gov.au/program/how-do-we-build-thenext-generation-of-affordable-housing/

Figure 32. Mein, T. (2013). McIntyre Drive Social Housing Altona. NGV. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/ program/how-do-we-build-the-next-generationof-affordable-housing/

Designed and constructed by a developer who retains ownership and management of the building and rents out apartments to tenants. Tenants have more flexibility in terms of their living space, and can choose to move around the building as their living requirements change, The buildings typically include a more amenities than other types of complexes.1

Mixed-use developments which act as de-centralising satellite hubs combining residential, retail, hospitality, recreational facilities, libraries, and medical and child care centres. A ‘densified’ model of living which aims to avoid the social alienation common in the suburban context. It focuses on mixing demographics – age, ethnicity, income groups for social sustainability and individual wellbeing.1

1 Duncan, A. (2021). What is build-torent? Canstar. https://www.canstar.com.au/ home-loans/build-to-rent/

Figure 33. COX. (2021). A Stable Future for Australian Renters. https://www.coxarchitecture. com.au/latest/a-stable-future-for-australianrenters-how-build-to-rent-is-reshaping-thehousing-market/

1 McGillick, P. (2020). An Exploration Of Emerging And Exisiting Housing Typologies. Habitus Living. https://www.habitusliving.com/ architecture/emerging-housing-typologies

Figure 34. WOHA. (2018). Kampung Admirality Habitus Living. https://www.habitusliving.com/ architecture/emerging-housing-typologies

A not-for-profit organisation that provides apartments that are socially, financially and environmentally sustainable. The apartments are sold to residents and Community Housing Providers, not investors, and because they are built for people, not profit, they invest time and effort in reducing the long-term cost of ownership. Things like rooftop solar, embedded energy networks, avoiding gas supply, and a shared super-fast commercial internet connection mean lower ongoing costs.1

1 McLeod, J. (2021). We make homes for people. Nightingale Housing. https:// nightingalehousing.org/

Figure 35. Hawson, M. (2014). The Commons by Breathe Architecture. Habitus Living. https:// www.habitusliving.com/architecture/emerginghousing-typologies

Secure, affordable, long term rental housing managed by not-for-profit organisations for people on low incomes or with special needs.1 A number of families united to create their own neighbourhood, living in separate houses but owning the land collectively. A community with shared facilities, common house, kitchen, dining, gardens, play areas.

1 Housing Vic. (2021). Community housing. https://www.housing.vic.gov.au/ community-housing

Figure 36. Breathe. (2014). The Commons. https://www.breathe.com.au/project/thecommons

There is an opportunity to transform the residential precinct into a mixed use precinct by enabing the surrounding mix of uses to bleed into the site.

This will blur the boundaries and edges of the site to make the precinct more inclusive of its surrounding areas, and bring more vibrancy, diversity and activation to the site. It will be a continuation of the surrounding areas, rather than a separated silo.

Clusters of uses within the site will allow communities to form and create a more diverse variety of character and activity throughout the site.

Concept design focuses on ideation and translating the research and theory into the physical form. Quick sketches were made to capture ideas that came up during research and creative thinking, which were shown in the previous chapter. This phase was about constantly shifting from messy, creative work to organised and systematic thinking. This was a helpful process in capturing a lot of ideas and quickly testing which ideas could help respond to my research questions. The end of this process resulted in a quick summary and parti diagrams of the concept so far.

As the largest open space in dense urban areas, the public housing sites can operate as green lungs with open parks, tree canopies and diverse planting.

The green lung breathes life into the surrounding dense urban area. It offers a place to connect with nature, biodiversity to thrive and lower urban temperature.

The green lung is the centre of the village. With an 800m radius the green lung can be reached by everyone in less than 10 minutes walking.

The formula is repeated throughout the city, creating a city of villages each with its unique character and anchored by the green lungs.

1.EXISTING

4.MOUNDS&VALLEYS

2.RETAINTREES,TOWERS&CHURCH 5.INTRODUCERESIDENTIAL

HISTORICAL HALL / CHURCH

SUNKEN PLAZA

EARLY LEARNING

SENIORS VILLAGE

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

CARPARK / VERTICAL FARM

PLAYGROUND

WORK/LIVE HOUSING

EDUCATION

SPORTS

The sketch design process focused on responding to the feedback about concept design and starting to look at design responses more at the human scale. In particular, the detail design of the Wellington tower was made the focus. The masterplan and key design drivers were returned to throughout the design process to make sure each decision was in line with the thesis questions and research. Precedent research and understanding existing examples of my ideas was a key factor in the design process. Sketch design allowed my to push bold ideas to see what was possible without too many practical constraints.

Low density housing in between two high rise apartment towers. A mixture of townhouses, walk-up flats and apartments.

273 walk-up flats = 546 bedrooms

66 townhouses = 198 bedrooms

6 duplex = 12 bedrooms

660 apartments = 1140 bedrooms

Total dwellings = 1105

Total Bedrooms = 1896

The feedback from this concept design was that the density appears too similar to the existing site. Assuming a mixture of 1, 2 and 3 bedrooms to calculate the density.

New residential = 1094 bedrooms

Existing apartments = 1140 bedrooms

Total Bedrooms = 2234

Increased by 17.8%

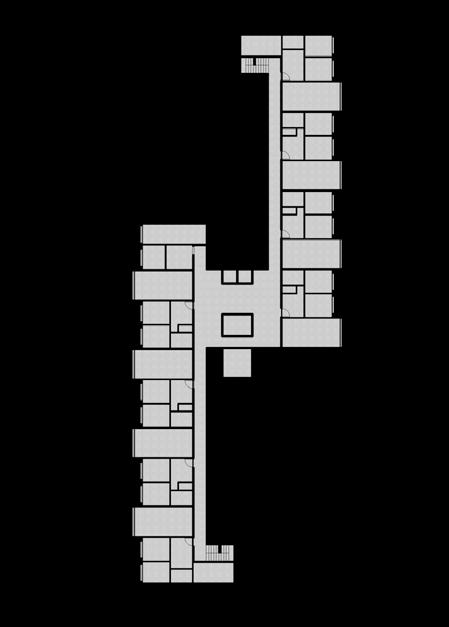

Low density housing in between two high rise apartment towers. A mixture of townhouses, walk-up flats and apartments.

273 walk-up flats = 546 bedrooms

66 townhouses = 198 bedrooms

6 duplex = 12 bedrooms

660 apartments = 1140 bedrooms

Total dwellings = 1105

Total Bedrooms = 1896

Apartment extensions = 48 bedrooms

New tower apartments = 168 bedrooms

Apartments = 1299 bedrooms

60 Townhouses = 180 bedrooms

27 Live / Work Townhouses = 81 bedrooms

660 existing apartments = 1140 bedrooms

Total Bedrooms = 2436

Increased by 28.5%

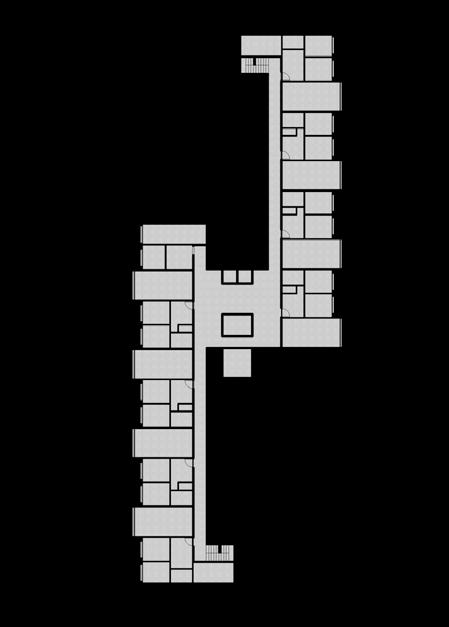

NEW APARTMENTS

NEW APARTMENTS

NEW APARTMENTS

CAMP

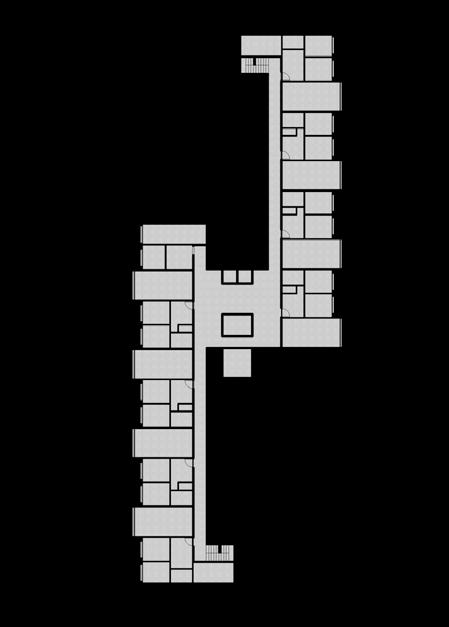

People walk through a narrow corridor to reach their apartment, there is limited access to northern light.

New front doors for residents and sun room community space with vertical circulation. The large floor plate creates issues with light access within the apartments below.

New balconies for residents, extending their living space. This solution offers more light into the living spaces, but apartment access is still through a corridor.

Light shafts allow light into bedroom windows below. Apartments are extended to include semi-private space and opportunities for chance encounters in their “front yard”.

LIVING & KITCHEN

Lifts travel direct to the base level of each neighbourhood, then residents use the communal open staircase to reach their apartment. This will increase chance encounters between residents as they travel to their apartment. The second lift will be used for disabled access if needed. Circulation in front of apartments and semi-private living spaces will also promote social connection between neighbours.

Mass timber including glulam columns and CLT panels will be used as a sustainable solution and to add some warmth to the existing concrete building. The neighbourhoods will be contained by wire mesh to allow for a connection to nature.

At the ground plane, apartments will be extended to allow for multigenerational families to occupy, and residents have the chance to occupt the retail space below their apartment. The ground plane will be contstructed with bricks recycled from the site, adding tactility and reducing waste.

One of the critiques with this sketch design was that the hit and miss communal spaces is creating a waste of structure and is not very efficient.

Void space in front of the bedroom windows allows for privacy and light to enter the apartments and also allows for visual connection between the 3 storeys, further encouraging social connection between residents. The apartment living space is extended by adding a new front door and semiprivate front yard with substantial access to sunlight. Residents can customise their apartment facade, adding more character and diversity to the building as their neighbours walk past.

The feedback from this sketch design is that there may be some privacy issues with people walking past bedroom windows, and there may not be many people walking past each other to create interaction between neighbours.

Makers Street is defined by a series of live / work lofts that allow residents to occupy a small shop, workshop, gallery or other creative space. This street celebrates the diverse cultures of the people living in this precinct, and the architecture respects the village scale of the former townhouses. Fine grain and tactility is introduced to the building form on the ground plane with the use of bricks recycled from the site.

Moving forward from sketch design and responding to critiques, the design development phase involved testing a lot of ideas. Different design options and solutions were tested alongside material choices and structural considerations. Structural and fire engineers were consulted to assess the legitimacy of the design and test any issues or contraints it had. It took a number of iterations to arrive at the final deign and achieve a balance between a practical and beneficial solution and an ambitious and bold design.

By 2050 the move towards mass timber contruction will be significant, and is a sustainable and efficient option for this project. Mass timber is strong, easy to manufacture, fast to assemble and more sustainable than steel and concrete.1 Timber also has biophilic properties and will improve the warmth of the building for residents and their feeling of connection to nature.

Cross-laminated timber comes with huge environmental advantages and outperforms steel and concrete on multiple levels. It can self-support buildings up to 12 storeys with no need for structural beams and columns.

Glulam structural posts and beams can offer structural support for 30 storeys. As building height increases, so does the size of the beams.

The benefit of prefabricated timber components is the speed of construction. The basic structure for a 12-storey mass timber building could go up in as little as 12 days, compared with a more typical timeline of three months.2 Construction is also quieter by reducing the number of workers on site and the need for heavy equipment. Foundations are less extensive because of timbers lightweight properties.

Mass timber is engineered to just as fire-resistant as concrete or steel. This is often done with a “charring layer” which acts as a buffer for fire resistance. This protects the interior (and structurally essential) layers from further combustion. If charred, they can be replaced rather than demolished.

1 Sidewalk Labs. (2020). Sidewalk Toronto. https://www.sidewalklabs.com/toronto

2 Sidewalk Labs. (2020). Sidewalk Toronto. https://www.sidewalklabs.com/toronto

Brock Commons is one of the world’s tallest buildings with a timber structure at 18 floors and 53 meters. The use of timber reduced the construction timeline to just 70 days after the prefabricated components were ready. Unfortunately the timber structure is concealed in the interior to comply with fire-safety codes.

This is a local example of a multistorey timber structure in Melbourne. It uses use pre-fabricated structural timber Glulam column and beam and CLT floor. The joints have been detailed nicely to appear seamless and services are able to pertrude through small holes cut. This building is 6 storeys and the only timber struture in the larger Melbourne Connect complex.

Figure 38. Naturally Wood. (2017). Inside Vancouver’s Brock Commons, the World’s Tallest Mass Timber Building. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/879625/inside-vancouvers-brockcommons-the-worlds-tallest-timber-structuredbuilding

Figure 37. Author’s photogrpah

COMMUNAL

RE-SKINNING

INCREASE PRIVATE AMENITY

INCREASE YIELD

Figure 40. Van der Burg, M. (2018). Klencke / NL Architects. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/902790/klencke-nl-architects?ad_ medium=gallery

Figure 39. MAISON EDOUARD FRANÇOIS https:// divisare.com/projects/223923-maison-edouardfrancois-paul-raftery-coming-out

Figure 41. Piuarch. (2012). Piuarch: Bentini Headquarters. Design Boom. https://www. designboom.com/architecture/piuarch-bentiniheadquarters/

Figure 42. https://www.cfmoller.com/p/MaerskTower-extension-of-the-Panum-complex-at-theUniversity-of-Copenhagen-i2732.html

Figure 45. Berndtson, H. (2020). Ørsted Gardens Apartments / Tegnestuen LOKAL. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/948801/orstedgardens-apartments-tegnestuen-lokal

Figure 46. Ruault, P. (2016). Transformation of 530 dwellings. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/915431/transformation-of-530-dwellingslacaton-and-vassal-plus-frederic-druot-pluschristophe-hutin-architecture

Figure 43. LAN. (2014). Rennes. https://www.lanparis.com/en/projects/rennes-1

Figure 44. https://architectureau.com/articles/avertical-forest-has-won-the-2014-internationalhighrise-award/

SECTION A

SECTION B

SECTION C

APARTMENTS

TOWNHOUSES

AGED CARE

APARTMENTS

VERTICAL NEIGHBOURHOODS

UNDERGROUND ROLLER DISCO

VERTICAL NEIGHBOURHOODS

ROOFTOP GARDEN

COMMUNAL AREA

NEW APARTMENTS

EXISTING CIRCULATION

COMMUNITY GARDEN

SEMI-PRIVATE FRONT YARDS

EXISTING APARTMENT

EXISTING CIRCULATION

EXTENDED APARTMENT

DROP / PICK

ROOFTOP GARDEN

NEW APARTMENTS COMMUNAL

WINTER GARDENS

EXTENDED APARTMENT

EXISTING

WINTER GARDENS

DETAIL 1

DETAIL 2

BALCONIES

EXTENDED APARTMENT

RETAIL

0 150m 12m

EXISTING APARTMENT LOUNGE ROOM

EXISTING APARTMENT BEDROOM

EXISTING APARTMENT LOUNGE ROOM

TILES GRADED DOWN TO DRAIN

500 x 500 GLULAM BEAM

500 x 500 GLULAM COLUMN

WITH RECYCLED OCEAN PLASTIC LINING BOX

CLT FLOOR

EXISTING APARTMENT LOUNGE ROOM

EXISTING APARTMENT BEDROOM

EXISTING APARTMENT LOUNGE ROOM

I BEAM BRACING EXISTING STRUCTURAL WALLS

NEW DOOR

OPERABLE PERFORATED METAL LOUVRES FOR SHADING

OPERABLE LOUVRES FOR VENTILATION

NEW INSULATION GLAZING

500 x 500 GLULAM BEAM

CLT FLOOR

APARTMENT

INDOOR / OUTDOOR TERRACE

COMMUNITY GARDEN

ELECTRIC BIKE & SCOOTER CHARGING

SEMI-PRIVATE LOUNGE

APARTMENTS EXTENDED

EXISTING APARTMENTS

NEW 1 BEDROOM APARTMENT

NEW WINTER GARDEN

NEW 3 BEDROOM APARTMENT

COMMUNAL AREA BELOW

COMMUNAL GARDEN BELOW

SEMI-PRIVATE LOUNGE

EXISTING APARTMENTS

SEMI-PRIVATE LOUNGE

NEW APARTMENT BUILDING

COMMUNAL AREA

NEW 1 BEDROOM APARTMENT

DINING

KITCHEN

SEPARATED OR JOINED ENTRANCE

Art Review. (2021). Pritzker Prize awarded to social housing duo Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal https://artreview.com/pritzker-prize-awarded-tosocial-housing-duo-anne-lacaton-and-jean-philippevassal/#:~:text=The%20French%20architects%20 have%20adopted,’&text=The%20prestigious%20 Pritzker%20Prize%20has,Lacaton%20and%20 Jean%2DPhilippe%20vassal.

BKK Architects. (2009). Tower Turnaround. https://bk-k.com.au/projects/tower-turnaround Cutieru, A. (2020). The Rehabilitation of Post-War Housing Blocks in 7 Projects. ArchDaily. https://www. archdaily.com/935980/the-rehabilitation-of-postwar-housing-blocks-in-7-projects

Faleh, M., Cook, A.,Haw, A., & Carrasco, S. (2019). Paris? Melbourne? Public housing doesn’t just look the same, it’s part of the challenges refugees face. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ paris-melbourne-public-housing-doesnt-just-lookthe-same-its-part-of-the-challenges-refugeesface-110284

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Island Press.

Government Architect New South Wales. (2020). Designing with Country. https://cdn.sanity.io/files/64znbptb/ on/195dcdd4c5ceeb13fdc16055ce22a1342c608aca. pdf

Hromek, M. (2020). Aboriginal Design Principles. WSP. https://shared-drupal-s3fs.s3-ap-southeast-2. amazonaws.com/master-test/fapub_pdf/000Wagga/Aboriginal+Design+Principles.pdf

Institute for Economics and Peace. (2020). Ecological Threat Register. https://www. economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/09/ETR_2020_web-1.pdf

Lacaton, A., & Vassal, J. P. (2016). Transformation of 530 dwellings. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily. com/915431/transformation-of-530-dwellingslacaton-and-vassal-plus-frederic-druot-pluschristophe-hutin-architecture?ad_medium=gallery

Launch Housing. (2017). Response to the inquiry into the public housing renewal. University of Melbourne. https://msd.unimelb.edu.au/__data/ assets/pdf_file/0007/2603824/Submission-forthe-Inquiry-into-the-Public-Housing-RenewalProgram_Transforming-HousingJ-the-University-ofMelbourne-and-Launch-Housing_2.pdf

Levin, I., Arthurson, K., & Ziersch, A. (2014). Social mix and the role of design: Competing interests in the Carlton Public Housing Estate Redevelopment, Melbourne. Cities. https://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/ S0264275114000481?via%3Dihub

Merin, G. AD Classics: Ville Radieuse / Le Corbusier. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/411878/adclassics-ville-radieuse-le-corbusier

Morgan, B. (2022, March 17). Big Ideas [audio podcast]. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/ programs/bigideas/loving-nature-and-revitalizedcities/13791316

Nikologianni, A., & Larkham, N. (2022). The Urban Future: Relating Garden City Ideas to the Climate Emergency. Land 2022. https://www.mdpi. com/2073-445X/11/2/147/htm

RMIT University. (2018). Creating liveable cities in Australia. https://cur.org.au/cms/wp-content/ uploads/2018/09/melbourne-city-score-cards.pdf

Rockström, R. (2017). Beyond the Anthropocene. World Economic Forum. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=V9ETiSaxyfk

Schmidt, M., Sanders, J., & Charles, A. (2020, October 13). Reimagine [audio podcast]. https:// www.reimaginepod.org/episode/ep-8-how-citiessurvive-and-thrive

Takada, K. (2020). Koichi Takada Unveils World’s Most Dense Vertical Gardens. Koichi Takada. https:// koichitakada.com/news/hello-world/

Victoria State Government. (2017). Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 Summary. https://www.planmelbourne. vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/377127/ Plan_Melbourne_2017-2050_Summary.pdf

World Health Organisation. (2017). Urban Green Space Interventions and Health. https://www.euro. who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/ urban-health/publications/2017/urban-greenspace-interventions-and-health-a-review-ofimpacts-and-effectiveness.-full-report-2017