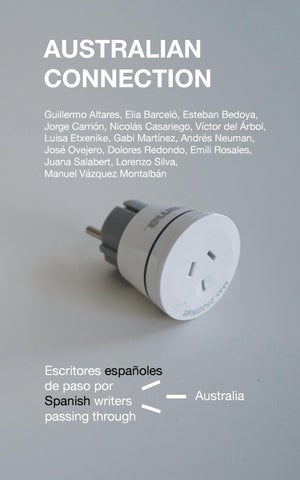

AUSTRALIAN CONNECTION Guillermo Altares, Elia Barceló, Esteban Bedoya, Jorge Carrión, Nicolás Casariego, Víctor del Árbol, Luisa Etxenike, Gabi Martínez, Andrés Neuman, José Ovejero, Dolores Redondo, Emili Rosales, Juana Salabert, Lorenzo Silva, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

Escritores españoles de paso por Spanish writers passing through

Australia