We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all individuals and organizations who have contributed to the success of this journal. Their support, expertise, and commitment have played a crucial role in the publishing of the first Project UNITY Summer Journal. We would like ot express our appreciation to the following:

We appreciate the advisory board, a group of distinguished professionals at the forefront of healthcare, public health, and academia

Our partners have been instrumental in fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange. We appreciate their ongoing support and commitment to advancing public health initiatives.

A special mention to our dedicated interns for their hard work throughout Catalyst Academy, producing remarkable blog posts and research papers.

We thank the international Collegiate Journal of Sciences for editing and publishing our student papers.

Public Affairs Committee members have been dedicated to formatting, editing, and ensuring the quality publicatoin of the first issue.

At Project UNITY, we recognize that transformational change requires a collaborative effort, and we work to bring together individuals, organizations, and communities from all backgrounds to create meaningful and sustainable solutions. Our programs are designed to address the unique needs of each community we serve, with a focus on building capacity, promoting self-reliance, and empowering individuals to lead the change they wish to see in their communities.

Whether we’re working to improve public health outcomes, providing access to education and mentorship, or creating spaces for community engagement, we’re driven by a passion for positive change and a commitment to making a difference in the world.

Project UNITY is a 501(c)(3) Non-Profit Organization focused on building the next generation of public health leaders and collaborating with diverse community leaders to build a grassroots coalition, collectively advancing public health equity across our evolving healthcare ecosystem.

Our vision at Project UNITY is to provide vulnerable populations with the knowledge, skills, and resources to become self-motivated in prioritizing their health. We envision a world where public health is a right, not a privilege, and where every child has the opportunity to receive quality education and mentorship. We aspire to be a catalyst for positive change by bringing together diverse communities and empowering them to take action towards sustainable development. Through our work, we aim to inspire a culture of empathy, as we contribute to building a bright future for the current and future generations.

Project UNITY is a Nation-Wide Youth Led Effort comprising of High School, Undergraduate, Medical School, and Graduate Students.

Morish Shah

Pranav Mehta

Sneha Shenoy

Shubghangi Patel

Sarah Guo

Alex Elamine

Maddie Brooks

Mahima Dave

Haley Stark

Nimisha Kumar

Rojie Ekanayake

Morish Shah

Pranav Mehta

Sneha Shenoy

Shubghangi Patel

Sarah Guo

Alex Elamine

Maddie Brooks

Mahima Dave

Haley Stark

Nimisha Kumar

Rojie Ekanayake

Ryan Wen

Annika Simmons

Nisha Das

Jiya Patel

Ella Valencia

Neha

Jasti

Varun

Natarajan

Grace

Liu

Xandro Xu

Jadon

Gamoa

Ryan Wen

Annika Simmons

Nisha Das

Jiya Patel

Ella Valencia

Neha

Jasti

Varun

Natarajan

Grace

Liu

Xandro Xu

Jadon

Gamoa

Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at Loma Linda University and founding President of Anekant Community Center (ACC)

Chairman and CEO of MIMIT Health and Professor at Interventional Radiology of Rush Medical College

Co-Director of the Rice-UT Public Health Scholars Program and Professor at Rice University

Chief Information and Digital Health Officer at UC Davis Health and Professor of Gastroenterology

Faculty Associate at the Institute for Implementation Science at the University of Health Sciences Center Houston

Project Manager in Technical Strategies and Innovation at the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation

“Health is the best wealth one can ever have. That’s why Project UNITY’s Focus on Public Health Education is crucial for the next generation of leaders.” - Dr. Shah

“Project UNITY is important because Public Health is Important.” - Dr. Diep

Assistant Dean and Professor of Public Health at Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine at Nova Southeastern

“It was extremely inspiring to see so many young and driven professionals come away with a deep appreciation of Public Health from Catalyst Academy.” - Dr. Hashmi

“I am proud of Project UNITY because it’s empowering youth and its working in helping vulnerable populations with evidence based solutions.” - Dr. Chopra

Dr. Ahmar Hashmi MD, MPH Dr. Nitin Shah MD Dr. Cassandra S. Diep Ph.D Dr. Romi Chopra MD Dr. Ashish Atreja MD, MPH Laura Reynolds Dr. Kristi Messer DHCScProject UNITY is dedicated to educating the next generation of global public health leaders, fostering equity at all levels, and strengthening healthcare ecosystems. Through our initiatives, we empower vulnerable communities, advocate for social justice, and drive public health initiatives in policy, education, and outreach. As a diverse group of young leaders, we are committed to using the power of our voices to build a grassroots coalition, advance health equity, and create lasting change.

Collaborating with community organizations, schools, and non-profits, UNITY designs tailored interventions to address health disparities. Recent workshops, such as those on cardiac health and healthy eating in elementary schools, demonstrate our commitment to community-specific health improvements.

Catalyst Academy:

An immersive educational program for high school students nationwide. Catalyst Academy empowers participants to contribute actively to public health through research, publication, and practical interventions. The program fosters essential skills such as collaboration, public health proficiency, and leadership, with a lifelong support network

Themed monthly webinars engage audiences in critical health discussions. Experts and professionals lead open conversations, providing actionable solutions. UNITY ensures audiences learn about diseases and immediate steps for community improvement.

Bridging the mentorship gap, UNITY connects students with professionals for personal and career guidance. The goal is to provide every child with educational opportunities. Upcoming expansions aim to broaden the reach and impact of mentorship programs.

Advocacy:

Collaborating with legislators, UNITY advocates for increased public health education in schools. The goal is to issue proclamations and raise legislative awareness about the importance of equity. UNITY envisions every school offering a foundational public health course.

Health Equities Town Hall Series:

Collaborating with universities and organizations, UNITY hosts town halls nationwide focused on achieving health equity. Diverse panelists, including politicians, physicians, faculty, students, and community members, drive conversations and inspire actionable steps toward a healthier future.

UNITY Podcast:

The UNITY Podcast provides a national platform for discussions on public health. Interviews with healthcare leaders, patients, and community members educate listeners on various public health issues, progress, and steps toward health equity.

The UNITY Internship Program offers students experiential learning opportunities, engaging them in real-life work within an emerging non-profit. From shadowing professionals to volunteering in healthcare facilities, UNITY aims to shape the next generation of public health leaders.

ProjectUNITY’sholisticapproachcombineseducation, advocacy,mentorship,andcommunityengagementtomakea lastingimpactonpublichealthandequity.Joinusinadvancing healthinitiatives,buildingagrassrootscoalition,andcreating positivechange.

Catalyst Academy is a vibrant and transformative virtual educational program, specifically tailored for high school students with a keen interest in public health. Over the course of eight weeks, the Academy offers an immersive experience that is both intellectually stimulating and practically engaging. This program stands out for its interactive format, which includes live sessions led by eminent speakers and experienced college mentors. These sessions are designed to not only impart knowledge but also to inspire curiosity and foster a passion for public health. The virtual nature of the program allows for a diverse cohort and geographically widespread enrollment, bringing together a rich tapestry of perspectives, backgrounds, and ideas.

The core mission of Catalyst Academy is to nurture the next generation of public health professionals. It aims to ignite a spark of curiosity and a deep-seated understanding of public health issues among high school students. The program meticulously blends theoretical learning with real-world applications, encouraging students to delve into rigorous research. They are guided to explore and articulate their findings on pressing public health concerns, culminating in the publication of their work in the UNITY Summer Research Journal. The Academy also emphasizes the development of practical skills. Through the design and execution of public health interventions, students not only apply their theoretical knowledge but also develop critical life skills such as teamwork, leadership, effective communication, and public speaking.

Catalyst Academy utilizes an Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) approach, working with the community for the community. This means that we recognize and leverage the strengths and resources already present within the community. We believe in empowering community members as active participants and co-creators of solutions to public health challenges. Through this approach, we foster sustainable change that is rooted in local knowledge, expertise, and ownership.

Catalyst Academy leaves an indelible mark on the community through various channels:

Educational Enrichment: We serve as a beacon of knowledge, enlightening young minds about the complexities and nuances of public health. This education extends beyond a ‘traditional’ classroom setting, encompassing a deeper understanding of how public health issues affect societies.

Skill Advancement: The Academy is a crucible for skill development. It goes beyond academic learning, instilling practical skills that are vital in both personal and professional realms. Students emerge as more effective communicators, collaborators, and leaders.

Community Health Contributions: The practical interventions designed by students are not just academic exercises; they have real-world implications. These projects address actual public health challenges, making a tangible difference in communities by improving health outcomes and raising awareness.

Leadership and Mentorship Growth: Catalyst Academy is a nurturing ground for future

The Public Health Conference Awards honor the outstanding achievements and contributions of students who have demonstrated exceptional dedication and innovation in the field of public health. These student scholars are shaping the future of public health through their passion and commitment to the field.

This award recognizes the group that delivered the most compelling and engaging poster presentation during the UNITY conference. This team is spotlighted for their outstanding research and development of their academic poster. We also applaud the presentation of their deliverable in a clear and concise manner with the utmost level of professionalism.

RECIPIENTS:

This award celebrates the group with the best overall research paper, factoring in their detailed research content, professional writing skills, critical thinking capabilities, and overall scientific competency.

RECIPIENTS:

The Public Health Trailblazer award recognizes the two individuals who have demonstrated an extraordinary commitment to public health. These two individuals have not only excelled throughout their summer public health project, but have exhibited a relentless passion to lead public health initiatives in their community, sparked intellectual conversation with global leaders while providing support to their peers, and have shown a constant drive to sharpen their professional skills. Their exceptional leadership in nurturing and growing the first Catalyst Academy Program sets them apart as true trailblazers in the field.

RECIPIENTS :

This prestigious award is awarded to the group of individuals that have gone above and beyond the premises of Catalyst Academy, demonstrating exceptional leadership in public health this summer. These students have helped advance the Project UNITY mission and are vital pieces of expanding UNITY’s reach.

RECIPIENTS:

MIMIT Health

International Collegiate Journal of Science

CIMSS Innovative Solutions Cook with Communities Anekant Community Center PERIOD.

Student Health Equity Forum of Boston College

UC Davis Health

Harvard Medical School

Nova Southeastern University Rice University

Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

ChenMed

UTHealth Houston McGovern Medical School

UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine

Medicine, Neuroscience / By

Emma Bai, AdlaiE. Stevenson High School, Project UNITY, February 3, 2024 / In partnership with the International Collegiate Journal of Sciences

With a family member who has suffered from severe ADHD as a cause of dopamine deficiency, and a lifelong struggle with obesity, I saw from a young age the importance of addressing addiction as a result of dopamine deficiency. This blog post aims to cover the connection between dopamine deficiency and addiction to food and drugs.

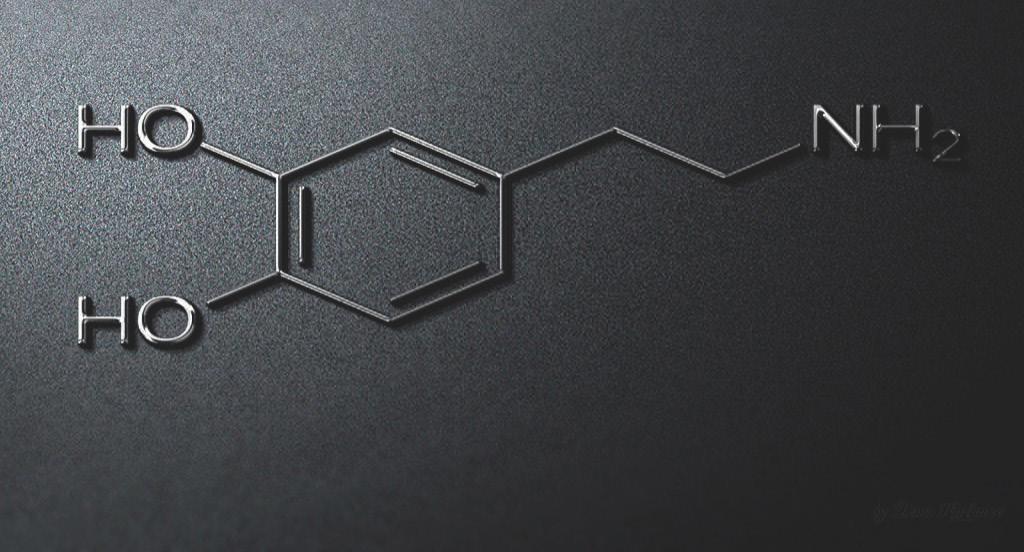

Commonly described as the “reward neurotransmitter” of the brain, dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps relay electrochemical messages through the brain and to the rest of the body. Produced in the ventral tegmental area of the brain, dopamine is released into the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex, allowing for signals triggering control of movement, memory, mood, pleasure, and cognitive abilities1. Low amounts of dopamine have detrimental effects on the body. Dopamine depletion can be caused by brain injury or hereditary conditions and is associated with widespread health problems such as obesity and drug addiction. Dopamine plays a fundamental role in satisfaction, pleasure, and happiness, and those who lack it seek these feelings from actions that produce positive sensations2 . These behaviors often lead to a dependence on food or drugs for pleasure, and ultimately, addiction. The rest of the blog will dive into the correlations between dopamine deficiency and addiction.

Irregular dopamine caused by drug abuse and addiction can lead to behaviors that create a reliance on addictive substances. Dopamine is released in the mesolimbic pathway. Drugs act on this pathway, increasing dopamine transmission and damaging the pathway, creating an insatiable and ever-escalating need for the “euphoric” feeling3. With drug-related deaths nearing one million annually, over a hundred thousand in the US last year, the urgency of action against this epidemic is at an all-time high4 . And of the 100,000 individuals who died due to drug overdose in 2021, 80,000 of these deaths were caused by opioids. Opioids are drugs so accessible that while 93% of insurance plans cover opioids in the US with no restrictions, the drug buprenorphine – commonly used to treat opioid addiction – is included in only 35% of insurance plans in the US without restriction5 . Individuals deficient in dopamine are more likely to seek out these drugs as a counterfeit accelerator of the release of dopamine within the reward system. This allows for opioids to create a chemical imbalance in their brain and cause the lack of self-control that many addicts display.

Food addiction, while seemingly less urgent than drug addiction, affects many in the United States. With 41.9% of adults in the US facing obesity today, the issue should be treated as a national public health crisis6. Many factors play into obesity (e.g. genetics, poor sleep, environment), but a widely understudied factor that plays a large role in the rapidly growing obesity epidemic is the effects of irregular dopamine receptors in the brain, causing the heightened desire to indulge oneself and limit self-control.

The first study suggesting that food is addictive was conducted by Randolph in 1956, and from there only 9 more papers in the next 50 years were published suggesting the same. However, due to the rising concern over obesity rates in the US, and with recent breakthroughs in understanding the physiological mechanisms of obesity since the early 2000s, a boom of more than 65 papers have been produced since 20037. Some breakthroughs include studies showing that obese rats have downregulated striatal dopamine receptors similar to what is seen in drug addiction. In humans, it was found that repeated exposure to sugar induces more frequent dopamine release. Ultimately, those who have downregulated receptors are largely more susceptible to food addiction 2 . Another study concluded that dopamine transmitters are affected by the physiological state and access to highly palatable foods8 . Often, people have a habit of eating when negative feelings arise, most notably sadness, boredom, and high stress. The vulnerability to overeating is a common factor found in binge-eating disorders and is exacerbated by the accessibility of cheap, non-nutritious foods.

In both food and drug addiction, several efforts have been made to address dopamine deficiency in those affected. Harvard has recently done research on using exercise in combination with medication-aided treatment to combat addiction, showing increased abstinence rates compared with programs that focused on medication or physical activity separately 9. Treatments available for food addiction range from 12-step programs (e.g. Overeaters Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous), to cognitive behavioral therapy, to psychiatric intervention. To increase the success of these efforts, stigma surrounding food and drug addiction should be minimized, and an understanding built that those affected are victims that need help more than they need criticism. Once victims are treated sympathetically, they’ll be more willing to seek help without feeling guilty about needing to get care for themselves.

Food and drug addiction is a prevalent issue in the United States that needs to be addressed. Through communal support, remedies for those affected, and public awareness about the urgency of the epidemic, victims will feel less shame associated with the issues they’re dealing with. Through the experience of my loved ones and the research I’ve done for this blog post, I have seen the significance and need for change for those impacted by addiction both medically and socially.

Medicine, Neuroscience, Social Science / By Dipikkasri Dhananjeyan and Smriti Kumar, Adlai E. Stevenson High School, November 24, 2023/ In partnership with the International Collegiate Journal of Sciences

Abstract

Health literacy is the ability of an individual to find, understand, and use health-related services and information to maneuver the complex healthcare system in the U.S., and to advocate for themselves and their own health. The purpose of this literature review is to analyze health literacy in the U.S. population and the determinants that lead to low health literacy rates. By understanding these factors, the current health interventions promoting health literacy awareness, and any possible future intervention programs can be better devised to improve health literacy in the U.S. This literature review was conducted with scholarly sources from Google Scholar and PubMed, relevant to the keywords. Through analysis of various determinants of health, minority populations seem to be affected the most by low health literacy rates, especially due to factors such as low education levels, low socioeconomic status, cultural differences, language barriers, and insufficient community resources. To combat the determinants that contribute to low health literacy, awareness must be created to increase literacy rates. Targeted interventions for the specific demographics most affected must also be implemented to overall promote health equity.

Health literacy is the ability of an individual to find, understand, and use health-related services and information to maneuver the complex healthcare system in the U.S., and to advocate for themselves and their own health. The purpose of this literature review is to analyze health literacy in the U.S. population and the determinants that lead to low health literacy rates. By understanding these factors, the current health interventions promoting health literacy awareness, and any possible future intervention programs can be better devised to improve health literacy in the U.S. This literature review was conducted with scholarly sources from Google Scholar and PubMed, relevant to the keywords. Through analysis of various determinants of health, minority populations seem to be affected the most by low health literacy rates, especially due to factors such as low education levels, low socioeconomic status, cultural differences, language barriers, and insufficient community resources. To combat the determinants that contribute to low health literacy, awareness must be created to increase literacy rates. Targeted interventions for the specific demographics most affected must also be implemented to overall promote health equity.

Health literacy affects a huge percentage of the US population. 88% of US adults have substandard rates of health literacy, with 14% having below basic knowledge, 22% having basic knowledge, and 55% having intermediate knowledge of health information. This is a significant number of people, and steps must be taken to increase health literacy rates in the US15 .

Health literacy rates also differ by certain demographics. The older population, namely those 65 years or older, have the lowest levels of health literacy. In general, trends show that health literacy rates decline after the age of 40. These trends can be attributed to general decreases in cognitive ability in those of older ages, as well as unfamiliarity with digital tools currently used in the healthcare system. However, studies have shown that there is no significant difference in health literacy rates between men and women. By race, Hispanic and African American populations have the lowest health literacy rates, while White and Asian American/Pacific Islander populations have the highest health literacy rates. Also, health status correlates with health literacy, as 42% of those who reported poor health have below basic knowledge of health literacy15.

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) are uncontrollable conditions or factors that affect an individual which can impact their health and, in this case, health literacy rates. There are various determinants that affect a person’s health literacy knowledge in the US, including socioeconomic status, such as income and occupational status, education levels, cultural traditions, language, and community8 .

Education is perhaps one of the most important SDOH affecting health literacy. Many studies have found that the health literacy of an individual has a direct correlation to their level of education4 This is because education allows an individual to have an increased number of skills that can aid in understanding complex situations, such as navigating the healthcare system. In addition, higher education levels offer an individual more opportunities for success, which in turn increases their quality of life through higher income, better living conditions, and overall higher socioeconomic status relative to an individual who is less educated 23

As mentioned previously, higher educational qualifications tend to lead to a higher socioeconomic status, relating to wages and employment status, which is directly linked to increased health literacy and health promoting behaviors16 . Increased wages allows greater access to quality healthcare resources and treatments, as well as better living conditions, all of which promote health literacy. Moreover, an improved employment status can increase access to social resources and influence, which once again creates easier accessibility to different resources that can enhance health literacy20

However, those with lower socioeconomic status, namely minority populations who on average receive lower wages and older adults who are less

likely to be employed, are faced with inadequate resources and health literacy, increasing health implications25

Cultural beliefs are one of the key reasons that health literacy rates are low among certain minority populations. Cultural beliefs dictate various behaviors and practices, such as situations in which individuals seek treatment and from whom, as well as perspectives on various health problems11. For example, a certain health condition may be stigmatized in a certain culture, leading to an individual refusing to seek medical attention for the condition. Not only that, patient-provider communication can be greatly influenced by differing cultural beliefs, which can be less inclusive of certain cultures and may also decrease quality of care. One study found that African American individuals experience less patient centric visits, and patient-provider visits are often much shorter than those with White individuals, primarily due to less inclusive cultural environments in many healthcare interactions that can lead to less tailored and less informative care. Cultural barriers to health literacy are enhanced further by language differences14.

Language is an SDOH that stems from culture to affect health literacy rates. A large number of people in the United States have limited English proficiency; specifically, 21.6% of US residents don’t speak English at home. This affects their knowledge, awareness, and decisions within the healthcare system. This is mainly due to decreased communication ability with healthcare providers, which would mean that those who are not proficient in English will be less informed of their health condition and treatment options available14. Furthermore, differences in languages prohibit individuals from inquiring further about their conditions, which could leave them misinformed with regards to caring for themselves. Moreover, a lack of English fluency also affects a person’s ability to understand medication instructions, health education pamphlets, consent forms, and bills, as well as fill out forms at clinics, insurance claims, and more. Overall, language is a major barrier in health literacy levels22 .

An individual’s neighborhood and living environment can also affect their health literacy. While some neighborhoods have a plethora of resources available for individuals, such as hospitals, specialized clinics, educational centers, and safe spaces, other communities lack these. This in turn influences the medical services and reliable treatment options available for individuals living in these communities. Moreover, if an entire community’s health literacy rates are low, they may depend on questionable networks and sources of information, which may harm their health. For example, there could be certain stigmas embedded within a certain group in a community that could discourage individuals from seeking care as they are influenced by their community’s beliefs3 .

Low health literacy is directly linked to poorer health outcomes, as it is key in preventing and controlling any health conditions. Those who are not health literate may not understand health education materials and are less likely to get tested for any health conditions, preventing early diagnosis and treatment of various conditions, ultimately leading to worsened states of health. This is why low health literacy is often linked with obesity, poor nutrition, and lack of frequent exercise8 . Those who are not health literate have, on average, a 50% higher chance of hospitalization, with hospital stays longer by two days on average, and health care costs that are four times higher than for individuals who are health literate19. Moreover, those who are less health literate have a higher probability of frequenting the emergency room within 90 days of being discharged from a hospital 21. Also, individuals who have low health literacy are more likely to have comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, and are less likely to follow treatment plans or adhere to medication. Ultimately, these all lead to increased chances of mortality from various health conditions for the health illiterate population of the United States13 .

There are many challenges involved with distributing health literacy to all in the United States. Barriers involved with communication, shame, and quality schooling all tend to affect health literacy. Because the U.S. is filled with a diverse range of cultures, these challenges tied with racism and prejudice combine to become disadvantageous in certain communities, making health literacy inadequate in many populations.

Health literacy curriculums in schools are usually designed to assist students in grades 9 through 12 to identify and use reputable sources of high-quality health information, by describing how various sources influence personal health behaviors to teach the process of finding, understanding, and utilizing health-related materials. Quality education must be provided to high school students, and even children at young ages, to help teach how to prevent health problems and better manage health issues when they arise. Poor and inadequate education of health literacy from

they arise. Poor and inadequate education of health literacy from the start of a young to teenage age can lead to students being to be unfamiliar with medical terms or how their bodies work when they start to age. Due to this, usual patient education materials in hospitals and clinics have been suggested to be written at a sixthgrade or lower reading level, preferably including illustrations, for optimal comprehension of health literacy5.

These are some of the largest barriers to improving understanding health literacy for individuals in the United States. Language barriers cause miscommunications with treating health, low-literacy stigma prevents individuals from reaching out to for much-needed medical care, and low-quality education justifies corresponds to why individuals in the U.S. have low knowledge on health literacy. To address these challenges, measures must be taken to ensure rising health literacy rates in the U.S.6

Because the U.S. is filled with numerous immigrants from various countries, many individuals cannot understand, speak, read, or write in English. In fact, about 22% of individuals in the US do not speak English as their first language. Nevertheless, the U.S. uses English in many informational services like government, education, and commerce. This is very disadvantageous for immigrants or individuals who cannot understand the language that is used to disseminate health information, interpret medical charts, and utilize medical tools for personal and familial healthcare2 . It has been found that language barriers in healthcare may lead to miscommunication between a medical professional and patient, reducing both parties’ satisfaction and decreasing the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. Misunderstandings may occur in clinical situations in almost half of all healthcare interactions. Poor communication between clinicians and patients can result in misunderstandings about medications and miscommunication about follow-up instructions, resulting in the possibility of poorer outcomes. However, it has been suggested that implementing online translation tools may improve the efficiency of healthcare and the level of satisfaction among both medical providers and patients1 Stigma surrounding low health literacy refers to the shame caused by others or perceived by patients that is associated with the discovery of an individual’s low literacy ability. Low-literacy-related stigma can seriously diminish individuals’ spoken interactions with healthcare professionals and their potential to benefit from healthcare services, ultimately leading to poorer health outcomes, such as unsafe or inappropriate use of medications and a decreased use of preventive healthcare services24. Many patients do not feel at ease with their low health literacy levels, usually due to facing previous humiliation and degradation, preventing them from reaching out to much-needed medical providers. Health professionals must provide non-judgmental literacy-sensitive support and use simple terminology for patients to feel more comfortable with their literacy level and to promote positive healthcare experiences and outcomes9

The issue of health literacy can be addressed through various means. For example, health literacy can be spread not only through written methods, such as various brochures and pamphlets, but also by increasing general literacy and reading ability. Interventions can also include educational workshops that target various cultures and demographics. Technology can be leveraged to create a mass media health literacy awareness campaign, or to publish resources such as articles and videos in an accessible manner. Patient-provider communication is key as well, so interventions could educate doctors, nurses, and other professionals on how to assess whether a patient has low health literacy, and how to efficiently communicate with them to inform them about various health implications and treatments17 .

Across the United States, there are various initiatives that target health literacy. Over 20 states have organizations that specifically improve health literacy among the population, such as the Colorado Health Literacy Coalition and the North Carolina Program on Health Literacy. Moreover, various universities, specifically through their public health programs, create resources and tools for individuals to improve their health literacy. Finally, federal initiatives, such as the Affordable Care Act and the Plain Writing Act, improve health literacy rates in the United States12.

One such federal initiative is the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. The plan’s goals are to ensure health information and health equity for all by promoting the communication of health information in an accessible way. It involves key improvements to the healthcare system. These improvements include a set standards to assess health literacy, adequate resources for increased health literacy, and more thorough health education in schools and universities. The plan also involves the promotion of organizations and campaigns that increase health literacy access18 .Across the United States, there are various initiatives that target health literacy. Over 20 states have organizations that specifically improve health literacy among the population, such as the Colorado Health Literacy Coalition and the North Carolina Program on Health Literacy. Moreover, various universities, specifically through their public health programs, create resources and tools for individuals to improve their health literacy. Finally, federal initiatives, such as the Affordable Care Act and the Plain Writing Act, improve health literacy rates in the United States12 There are various tools available for assessing health literacy. For example, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine, Short Form, or REALM-SF, is a short test containing 7 words. The test asks individuals whether they recognize each word or not, and it is a quick method for healthcare providers to assess a patient’s health literacy. Another test is the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, or TOFHLA Numeracy, which assesses whether a patient can adhere to health care provider instructions. Overall, these tests are useful resources for healthcare providers to determine the best methods of communication to employ with a patient10

Overall, increased health literacy is necessary in the United States to improve health outcomes, especially in certain minority demographics and populations. Although there are currently many health interventions addressing the urgent issue of health literacy, there are some challenges that these interventions have yet to address, such as the stigma associated with some interventions, or even other determinants such as discrimination and culture. Ultimately, a wider range of targeted interventions must be designed to improve health literacy in the United States and eliminate its burden on the national population.

2024/ In partnership with the International Collegiate

Journal of SciencesIn a world where the rhythms of life are dictated by buzzing screens, imagine another where the rhythms are created by the gentle whispers of rustling leaves. In this universethere lies nature’s most powerful healing power: Ecotherapy. Or nature therapy. Ecotherapy is a unique, ancient approach to improving one’s physical and mental well-being. This form of therapy is not limited to prescription boxes or stuffy walls, but rather open to an unlimited amount of space and involves participation in outdoor activities within nature. In this blog post,the transformative potential of ecotherapy as a health intervention will be discussed.

Why Ecotherapy

From Ayurvedic medicine 1 to traditional Chinese medicine 2 to Western medical perspectives 3; 4 , nature has historically been linked to well-being. Nature has the ability to renew people’s spir-

its, whether they are in a city park, a forest distant from civilization, or simply strolling along a street surrounded with trees. Specifically, a quick stroll in nature can lower tension, keep one upbeat, and even enhance memory 5. Furthermore, the act of simply glancing at images of greenery or being surrounded in nature, for less than a minute, can improve one’s attitude6 .Interestingly, a recent study explored how the mood changes during a nature walk using portable EEG sensors. Researchers discovered that when subjects were walking in a green area as opposed to a crowded commercial district or a busy retail street, their brain waves were more likely to resemble those of meditation and they showed less dissatisfaction7

It is common consensus that connecting nature is one of the best parts of ecotherapy. One may feel even more rooted and a part of something greater than themselves after receiving this treatment.

According to studies on benefits of nature in a medical setting, A patient recovering from gallbladder surgery healed more quickly when they had a window viewing nature than if they did not have one at all8 . Additionally,those with a “view” of nature reported less anxiety and recovered faster. Moreover, viewing natural sights has also been found to promote positive thinking, reduce aggression, and soothe post-stress5.

Ecotherapy can also treat mental health complications such as depression and anxiety. By Combining outdoor exercise with the calming and restorative effects of nature, patients can reduce psychological symptoms and improve physical well-being by engaging in outdoor activities.

Ecotherapy can be performed through formal or informal approaches such as park prescriptions, animal-assisted therapy and community farming. Walking, hiking, or simply unwinding in a park or other natural setting are all examples of informal approaches. Whereas, formal methods like park prescriptions involve doctors advising patients to spend time outside as part of their treatment plan, providing patients a chance to get outside and enjoy the benefits of nature.

Animal-assisted therapy is when patients receive treatment with animals, such as dogs or horses. Being with animals in their natural environments can make people feel more at ease, less worried, emotionally attached, and reliable. Additionally, through community farming or gardening, individuals can come with soil, cultivate their own food, and develop prosperous relationships with their foods and accompanying peer’s. Altogether, these activities offer a sense of success and purpose and can promote social connections and a sense of belonging.

Integrating ecotherapy into everyday life and daily habits is a beneficial way to spend your free time. Some ways this can be done are by spending time outdoors, creating a possible nature corner in your home, or volunteering for environment initiatives. Establish a daily routine of going outside, even if it’s simply for a quick stroll around a nearby park or green space. Take breaks during the day to go outside, breathe in the fresh air, and become one with nature. Additionally, you can designate a section off in your house or workplace where you can incorporate natural materials. To add a touch of nature to your immediate surroundings, place potted plants, flowers, or tiny indoor gardens here, this way a sense of peace and connection to nature may be established. Lastly, you can start by taking part in local environmental initiatives or offering your time to organizations that are concerned with sustainability and conservation. Participating in initiatives like beach clean-ups, tree plantings, or wildlife conservation programs can help the environment while also allowing you to get the rewards of being outside.

Ecotherapy can be done anywhere. However, the key is to find ways to incorporate nature into your daily life that appeal to you as approachable and enjoyable. With simple, consistent steps, the benefits of ecotherapy and more fulfilling relationships with nature can be achieved.

On June 29th, 2023, the Supreme Court rejected affirmative action in U.S. colleges, marking the end of granting special consideration to minority students and women in college admissions1. This rejection also banned racebased consideration in medical school admissions. In the long run, this will significantly impact the diversity in the healthcare field. This article will discuss the effects of affirmative action in medical schools, healthcare providers, and the consequences for minorities.

On September 24th, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which prohibited discrimination in employment based on color, religion, race, or national origin 2 . Soon after, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), which works under the Department of Labor, wrote an affirmative action plan establishing equal employment opportunities for minorities and women 3. This order also applied to colleges and medical schools, allowing thousands of students from minority communities to be able to go to top schools and have the opportunity to become healthcare providers4.

However, on June 29th, 2023, the Supreme Court overturned this action stating that race can no longer be a basis for granting admissions5 Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that it violated the Equal Protection Clause, failing to show measurable reasons to justify the use of race6

This ruling can have serious consequences. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), representing over 500 hospitals and medical schools, argued that diversity can “literally save lives” 7. They added that having a diverse education can help healthcare providers care for a variety of patients from any background7. A study conducted in April of 2023 found that a 10 percent increase of Black primary doctors in a county can increase Black life expectancy by 30 days8 . Norma Poll-Hunter, the senior director of workforce at the AAMC, explained that a lack of diversity can reduce student, trainee, and physician confidence in treating patients from a different background than their own9 An analysis of six of the nine states that have already banned affirmative action found a 17% decrease in diversity after the ban was implemented7. This could mean that there will be an overall significant decrease in healthcare providers of color practicing medicine.

Past events such as illegal testing of blood donated for diabetes research from the Havasupai Tribe, the Tuskegee Experiment– where Black men were injected with syphilis without consent— and forced sterilizations of Puerto Rican women all have facilitated minority patients’ mistrust of doctors of different ethnicities than their own10 . As a result, patients from minority communities

are more likely to trust and feel more comfortable and safe expressing their concerns and issues with healthcare providers of the same race or ethnicity7.

Furthermore, the ban on affirmative action will only increase the health inequity gap between white and minority communities. A more diverse group of healthcare providers can produce better health outcomes for groups that have been historically marginalized11. Interestingly, a study done in Florida between 1992-2015 found that Black babies were twice as likely to die when cared for by a White physician compared to a Black physician9

Currently, Black patients’ pains and conditions are under-treated in comparison to White patients12 . Healthcare workers are more likely to refer to Black patients as people who just want a “fix”13. Consequently, Black patients are neglected the proper care and treatment, only making their conditions worse. Not only are they ne -

glected care, but individuals from minority races are less likely to visit the doctor, even when they have the services to go to14. A less racially diverse healthcare system will only reduce the protection against these biases and hurt minority patients15.

Although diversity was increasing within the healthcare system before affirmative action16 , current efforts to ensure that diversity keeps increasing are needed. The decrease in the diverse backgrounds of healthcare providers will not only increase the mortality rates of minority communities but will also push back the fight for racial equity and equality17. As America continues to become a more diverse country, individuals from minority communities must be granted the opportunities they deserve so that the voices of those who have been suppressed are heard and treated.

Medicine, Social Science / By Akshaya

Ganji, Adlai E. StevensonHigh School, Project Unity, January, 2024/ In partnership with the International Collegiate Journal of Sciences

The human brain, a complex organ powered by billions of neurons, orchestrates everything from conscious interactions to subconscious activities like breathing and digestion1. Yet, various factors in our society, deeply rooted in a capitalist framework, can impede brain functions and overall health.

Capitalism most certainly offers enormous benefits for healthcare. However, the lack of sufficient regulatory supervision often results in environmental and financial impacts on individual health 2

These outside factors then take a detrimental effect on the functioning of the brain. Since these factors are so widespread in our society, it’s become a major public health issue. Although numerous policies and initiatives have been implemented, the desired effect has been lost.

In recent years, mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression have surged, becoming commonplace in our vocabulary. The number of diagnoses are at an all time high. For instance, while 8.1% of adults showed symptoms of anxiety disorders in 2019 with 6.5% showing symptoms of depressive disorder and 10.8% showing symptoms of anxiety disorder, this number dramatically increased to 50% by 2023. (3.) (4.). In just four years, half the population has reported devastating symptoms associated with anxiety and depression. Although this dramatic increase can be partly attributed to Covid-19, efforts to reduce rates of anxiety and depression have been minimal. The rise in cases and insufficient efforts to mitigate this crisis highlights an urgent public health issue.

In an effort to aid the health of the country through a national stance, The National Institutes of Health (NIH) established “The Smart Health program”. This is an interdisciplinary approach that incorporates new technological and novel methods to transform our understanding of human brain activity in health and disease5.

Particularly, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms in this program have shown promise in preventative care and improving patient outcomes. Interdisciplinary teams are crucial to create scientific and engineering innovations that intelligently collect and analyze data from individuals and systems, enabling discovery and optimizing health outcomes. This program’s use of AI algorithms enabled doctors to take preventative measures and ultimately improve patient outcomes6 . A notable application of this program is Smart Health’s use of Virtual Reality (VR) therapy to treat mental health conditions. This is often an effective treatment option for mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, offering a direct platform for feasible and accessible medical care.7,8 With over 30% usage of smart devices by psychologists and mental health professionals, the treatment has a 60-70% success rate9, effectively supporting the rapid development of healthcare, while addressing pressing issues in the public health communities.

Furthermore, Smart device use has significantly improved physical, and psychological health of older adults, especially in urban areas and among those of greater age10 . Furthermore, according to the study, “How Does Smart Healthcare Service Affect Resident Health in the Digital Age? Empirical Evidence From 105 Cities of China”, “smart healthcare services have a significant positive impact on resident health.” With such incredible results and The National Science Foundation and the NIH’s support, interdisciplinary highrisk/high-reward research developing transformative advances will only further this impact to the next level.

Moreover, this specific program could effectively fund research projects such as exploring cutting-edge neural data science and AI techniques to comprehend the intricacies of the brain, creating novel multimodal models to quantify and interpret relationships between the brain and behavior across various scales, or designing revolutionary sensor systems to measure neural, cognitive, and behavioral functions in humans or other animals11.

This program collaborates across disciplines to merge fresh technological and conceptual approaches, aiming to revolutionize our comprehension of human brain function in both health and disease, setting the stage for other initiatives to do the same. With such funding from numerous programs, organizations could finally have the resources to implement their plans and interventions.

However, this program is not without its challenges. This is a high risk program that may feature a risk of bias in AI algorithms and data analysis, which may generate inaccurate predictions and patient assessments. Furthermore, since this is a new development within healthcare, the access to such equipment and program resources

12

are unavailable to the majority of hospitals, making it inaccessible to a significant portion of the population

While the intersection of brain health, public health, and technology presents exciting possibilities, it also entails significant challenges. Nevertheless, if necessary funding and education is prompted especially to underserved communities, patient treatment could be significantly improved, leading to a healthcare system that is inclusive and beneficial for all.

Emma Bai (Adlai E. Stevenson High School), Medha Modekurti (Adlai E. Stevenson High School), Rachel Varghese (Adlai E. Stevenson High School), Aamuktha Yalamanchili (Adlai E. Stevenson High School), Pranav Mehta (Rice University), Project UNITY, February 3, 2024

Abstract

Background: Since the 1900s, food insecurity (FI) has been a significant public health concern in Illinois, especially Chicago. There is an urgent need for community-focused intervention within Chicagoland and adjacent underserved communities. Objectives: The objective of this literature review is to investigate FI at a national and local level to design community-focused interventions that help underserved neighborhoods generate equitable resources. Methods: This literature review was conducted by synthesizing 116 scholarly sources that involved FI. Results: Black and Hispanic families are at the highest risk for FI. 24.9% of black and 19.3% of Hispanic families respectively nationwide, due to aspects of systemic racism, like redlining, and a lack of available resources. Several interventions have been undertaken to address FI within these communities, but food insecurity is still a persistent issue. Conclusion: Moving forward, more community-focused interventions should be emphasized in Black & Hispanic communities such as curriculum-based workshops, food drives, gardens, nutrition newsletters, and nutrition clubs. The interventions will improve food security and related disparities in Chicago, especially in the Black and Hispanic communities, by educating the youth and establishing hands-on initiatives providing more education, resources, and coalitions with local organizations.

Keywords: Food insecurity (FI), Chicago, Nutrition, Black and Hispanic Communities

Food insecurity (FI) has been a prevalent issue in American households for centuries. Every day, one in eight families in America is forced to decide whether to keep the lights on or feed their family due to FI. On a smaller scale, 1 in 11 individuals in Illinois face hunger, 1 in 9 of which are children. FI, defined as “…the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods”. Thus, the term not only refers to the scarcity of food, but also its poor quality, and the related health consequences for families and society at large1. In this literature review, we aim to outline the epidemiology of FI, the factors that contribute to FI, existing public health efforts, and possible future solutions to address this global issue.

The H.U.N.G.E.R initiative investigated 116 scholarly articles, through national literature review and evidence-based research within Chicago while also conducting two interviews with Chicago-based stakeholders: the principal of a local elementary school and the leader of an equity-promotion organization.

The National Literature Review gave us a clearer perspective and understanding of how FI affects communities across the country. We found that Hispanic and Black communities were the most at risk for FI. The significant social determinants of health for FI we found were: low-income or unemployment status, poor refrigeration conditions for food, and vast distance from food. FI has been found to severely impact the cardiometabolic system through complications such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, and congestive pulmonary disease2 . Additionally, FI can place adults in disadvantaged areas at higher risks for breast and colorectal cancer.

FI in the United States is measured in many ways. One common approach is the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) technique for determining calories “per capita” at the national level. The FAO interviews respondents in their homes to acquire high-quality dietary information about food-insecure groups. However, it may inaccurately track FI trends as it counts the amount of food that is available, not the amount of food that is eaten during the measurement period 3. Additionally, the nutritional intake of a person is measured using a variety of techniques, including meal frequency questionnaires, 24-hour recall, and food diaries4. These approaches depend on recall or observation. One can estimate portion proportions by weighing or using assisted memory. These estimates, which rely on precise food composition databases, assist in determining food group counts and nutritional intakes. Cutoff points are needed to determine the likelihood of nutrient deficits when interpreting nutrient intake. This may be beneficial as it addresses both macro and micronutrients as well as calorie intakes at an individual level. However, this method may lead to high measurement errors and biases, as it relies heavily on the participant’s memory. They would not only have to remember what they ate, but also, how much they ate.

There are a variety of government and community-driven efforts aimed at mitigating the effects of food insecurity, but they have significant shortcomings. SNAP is a government aid program that provides food benefits to low-income families, boosting their grocery budget so that they can buy healthy and nutritious food5 . However, SNAP may provide insufficient funds for families’ food expenses, especially for larger families. Many food pantries and soup kitchens limit individuals by only serving them one meal a day. Future research and interventions need to address FI as a public health crisis, not only by increasing anti-hunger programs but also by targeting the specific social determinants that impact each community’s FI. As a nation that is currently facing crises of starvation and obesity, we must support our communities through research, intervention, and equitable access to healthy foods.

Through our Evidence-Based Research (EBR), we found that Black and Hispanic families are at the highest risk for FI within Chicago. Chicago has a long history of redlining, blockbusting, and gentrification which also contribute to higher FI rates for minorities. Redlining can be defined as “a discriminatory practice that consists of the systematic denial of services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents of certain areas, based on their race or ethnicity”6 Blockbusting is the practice of introducing African-American homeowners into all-white neighborhoods to drive away White families and reduce housing prices7. Gentrification occurs when there is a rapid influx of middle-class or wealthy homeowners that move into poorer neighborhoods, rapidly increasing housing prices and displacing the low-income families that are living there8. Consequently, individuals in these places face numerous health implications such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension9.

FI impacts high-risk families on many levels – a reality that is captured by the socioecological model. On an individual level, education and disability contribute to FI. On an interpersonal level, marital status, parental education level, and parental employment all contribute to FI10 . At the community level, access to fresh foods (or lack thereof, in food deserts) and community-based interventions can impact the severity of FI as more than 20% of Chicago residents (3.3 million) live in a food desert11. A food desert is an urban community where it is difficult to find or buy healthy produce12 . On an organizational level, several food assistance programs, such as SNAP and The Greater Chicago Food Depository, provide aid to food-insecure families and individuals in Chicago. However, SNAPS’s benefits were cut short after COVID-19, decreasing by over $255.13 At the policy level, legislation has been implemented to reduce food insecurity. In Springfield, lawmakers are considering the creation of a grant program under the direction of “Senate Bill 850”. Proposed by Governor J.B. Pritzker, the program aims to alleviate the roots of violence and crime in Illinois by providing aid to independently owned stores14 . Additionally, in early 2023, Governor Pritzker signed a bill creating the Health Foods Access Program, which aims to provide equitable access to healthy foods all across the state by providing economic assistance to grocery stores, and plans on expanding to rural and underserved communities15.

Although there are several existing programs and a few recent initiatives, many food banks, pantries, and hunger organizations such as the Greater Chicago Food Depository and Feeding America are dissatisfied with the amount of legislative action taken. Larger advocacy efforts and support of local food banks is needed to increase access to healthy food.

Through interviews with various stakeholders, including Ms. Ann Hofmeier, the principal of Laura B. Sprague Elementary School, and Mrs. Nicole Laport, the Director of Communications at EAT Chicago, our team gained valuable social perspectives on FI in the Chicagoland area.

Ms. Hofmeier emphasized the need for a diverse curriculum-based nutrition program and transparent communication with parents. They explained how children also lack self-regulation skills that help them avoid unhealthy choices16. While positive options exist, the absence of a formal nutrition program is emphasized in the Evidence-Based Literature Review. Hence, comprehensive nutrition education in schools is crucial in addressing FI as it can empower students and parents, promote healthier food choices, and improve food security outcomes. Lack of education and knowledge about the consequences of limited access to proper nutrition contribute to many parents’ disengage-

ment with their child’s nutrition. This lack of knowledge perpetuates the cycle of FI, as parents may not fully grasp the impact that inadequate nutrition can have on their children’s health and well-being.

Mrs. Laport expressed the stark reality of FI stemming from systemic racism, gaps in the system, and inequality of access to food. There were many commonalities between our research and our conversations – for example, that food deserts and access to affordable, nutritious food are large issues that need to be addressed.

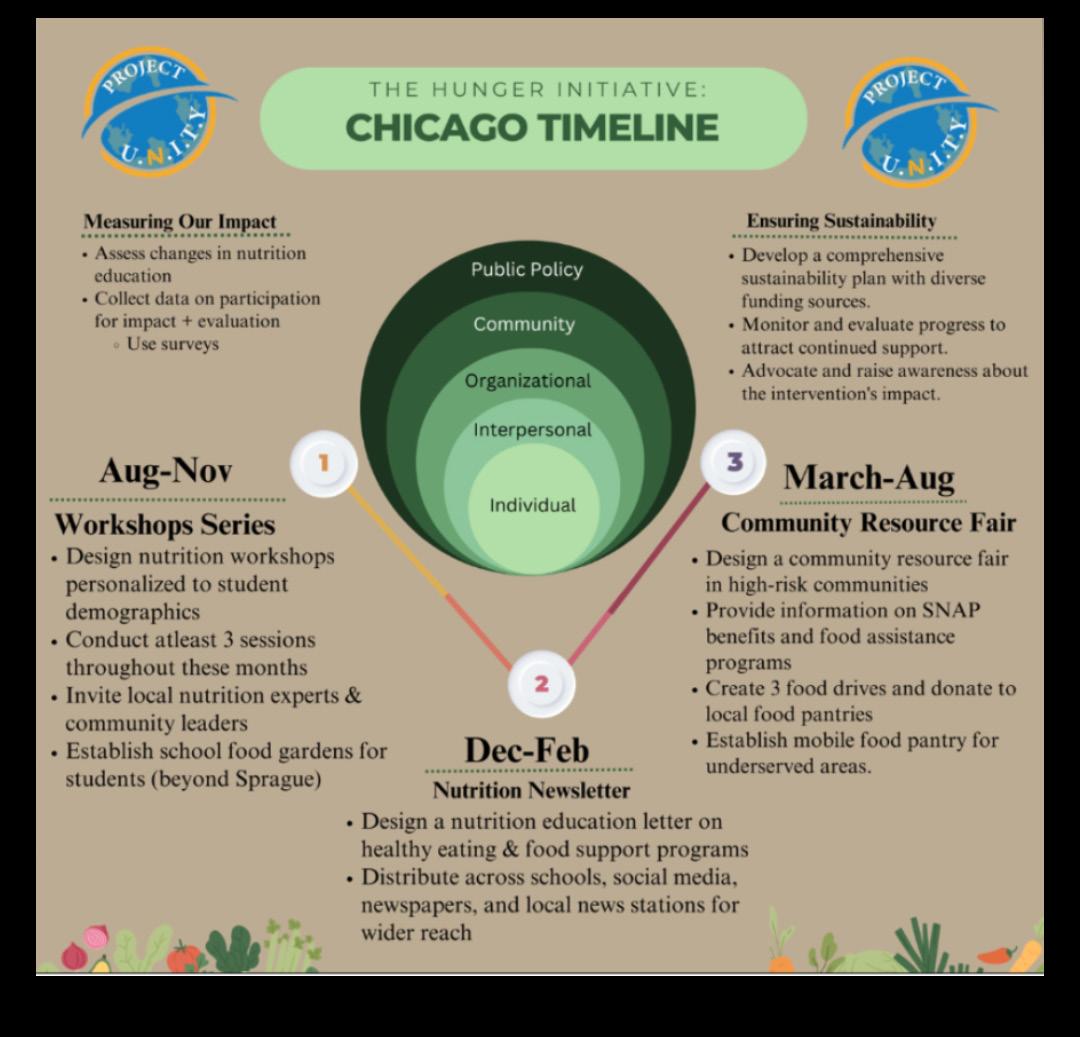

This action plan, which is divided into discrete phases, presents a strategic approach that will be implemented over one year’s time to further our commitment to nutrition education and community well-being. The approach moves toward complete efforts for sustainability, starting with an emphasis on evaluating changes in nutrition education, reviewing participation impact, and putting on interesting workshops. These include creating a thorough sustainability plan, ongoing monitoring and evaluation, and actively advocating for our solutions to increase public awareness.

The timeframe of the strategy is divided into three main sections: August through November, December through February, and March through August. In the first phase, interactive seminars with local nutrition experts and community leaders are highlighted. In the months to come, we’ll be focusing on expanding our audience by sending out a nutrition education letter on multiple platforms. Targeting high-risk populations, the approach culminates in a vibrant Community Resource Fair that includes essential elements including SNAP benefits information, food assistance programs, food drives, and mobile food pantries.

The curriculum-based workshops are available to not only children, but also adults on zoom to improve accessibility. To address the challenges associated with recruiting adults, who have less time to attend the workshop meetings, we will send out surveys to find a time that the majority of interested participants can attend.

Our nutrition newsletter will thoroughly educate households about food insecurity across demographic groups, discussing the historical roots of FI and current challenges. Outreach to diverse audiences is a major concern. By spreading the newsletter to all social media platforms and to local articles or newspapers, we will ensure widespread circulation.

The nutrition club will offer students unique experiences to increase exposure to healthy foods from a young age such as taste-testing sessions. To ensure students and school participation, we will actively seek student input through surveys, fostering inclusivity in the decision-making process, aligning club activities with their interests.

The food gardens and food drives will encourage student and communal participation outdoors. To address the sustainability limitation, we will create engaging activities and for food drives, we will offer incentives such as volunteer hours.

As our society continues to evolve, many fail to acknowledge the generational struggle of FI among minority and low-income communities, namely Black and Hispanic populations. Moreover, with factors such as inflation, stigma on food stamp usage, and high unemployment rates due to the COVID-19 pandemic, high-risk populations often resort to low-cost food with little to no nutritional benefits, leading to obesity and increasing health concerns across all age groups.

The EBR focused on more specific findings surrounding FI, some of which were similar to the National Literature Review. For example, Black and Hispanic populations are the highest at-risk for FI due to high unemployment rates, low incomes, and limited access to healthy grocery chains as well due to Chicago’s deep-rooted systemic racism. Although the EBR concluded that Chicago has lower rates of FI compared to the national percentage found in the Literature Review, more anti-hunger interventions are needed.

In addition, our interviews with Mrs. Nicole Laport of EAT Chicago, and Ms. Ann Hofmeier of Sprague Elementary provided us with deeper insight into FI in our nearby communities, emphasizing the immense need for nutrition education and shedding light on the stigma associated with asking for help in the context of FI.

The findings discussed in this paper reveal the extent to which FI is plaguing local and national communities. Understanding the extent of the problem is the first step to addressing hunger. The proposed plan of action effectively targets the social determinants of health in Black and Hispanic households. Educating the community, especially children, is the main focus of the plan and will ensure that future generations understand the importance of nutrition and ways to attain food security, tackling the cycle of hunger. Moreover, implementing community initiatives, such as food drives and mobile food pantries, will supply target populations with easy access to nutritious food. In addition, surveys and data collection will be conducted to guarantee the H.U.N.G.E.R. Initiative assists the community.

During the research process, our team found knowledge gaps in the existing materials on food insecurity, such as recent studies on FI, data on food-insecure Black and Hispanic populations, and Chicago-based programs. Possible explanations for these absences of information include the following: researchers may believe FI rates cannot drastically change in relatively short periods of time, there may be a stigma on nutrition in minority communities, and relying solely on national anti-hunger programs allows for emphasis to be placed elsewhere. All these areas must be further investigated to provide a more comprehensive and accurate view of FI while also combating the issue.

In conclusion, the urgency of the FI crisis cannot be understated. The issue affects far too many individuals nationally and locally and is predicted to keep growing. In particular, the Black and Hispanic populations in the Chicagoland area are most at risk for being food insecure and are the target of the H.U.N.G.E.R. Initiative. The proposed plan of action considers the social determinants of health that determine the extent of FI experience and utilizes curriculum-based workshops and community initiatives to both educate younger generations on nutrition and lessen the severity of hunger in the area. In the upcoming year, the plan will set future generations up for a healthy lifestyle while also supporting households that are currently facing FI. In the long term, the H.U.N.G.E.R. Initiative plans to establish a solid foundation for nutrition education in Chicago and expand it to the rest of the U.S. in hopes of addressing the present widespread malnutrition. Furthermore, diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and stroke can be prevented from afflicting much of the U.S. through proper nutrition, thus saving lives while restructuring healthcare. For now, consistent research measuring the extent of FI and initiatives that target various populations is the next step to achieving an ideal world where no one experiences hunger.

Ria Agarwal, Dipikkasri Dhananjeyan, Akshaya Ganji, Smriti Kumar, Dhruv Malladi, Morish Shah

Abstract

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) is the leading cause of mortality in the US. There is a lack of awareness on how to prevent CAD, as well as risk factors and social determinants of health (SDOH) that increase susceptibility to it, especially for the African Americans population. The purpose of this review is to analyze and synthesize the various factors that contribute to the susceptibility of CAD within the African American community in Illinois and the U.S more broadly. By recognizing these key components, an effective public health intervention can be designed and implemented to minimize the effects of CAD. This review was conducted using PubMed, American Heart Association Journals, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and other scholarly sources relevant to the keywords. Over 110 pieces of literature were reviewed and synthesized. The African American community is at the highest risk of CAD within Illinois and the United States due to biological, genetic, cultural, behavioral, and socioeconomic reasons. This includes hypertension, smoking, family history, segregation, redlining, and lack of quality healthcare in African American communities. Due to the various SDOH concerning African American communities, African American individuals are unable to receive the equitable quality healthcare needed to care for CAD, especially in Illinois. It is imperative for individuals to proactively initiate healthcare interventions that provide essential resources and education to empower the African American community.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Disease, African Americans, Social Determinants of Health, Prevalence and Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Diseases, Health Implications, Cardiovascular Health Interventions in Illinois.

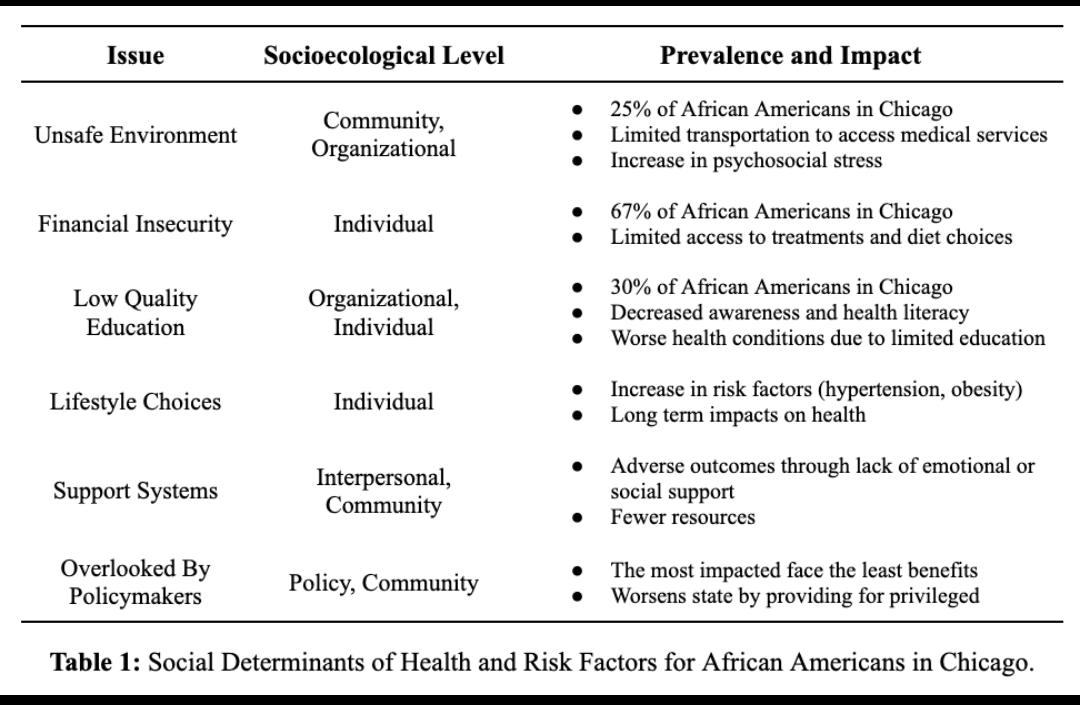

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is defined by plaque buildup in the coronary arteries, narrowing blood vessels and reduced flow of blood to the heart and body2 . Although Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) have impacted the U.S. and Illinois greatly, CAD in particular has had the most detrimental impacts both nationwide and locally. African American individuals statistically have the highest mortality rate from CAD in the United States5 , making it a significant public health issue. It is necessary to ensure that the large African American population in Illinois is protected from the effects of CAD, as African Americans compose 14.7% of the population, a large percentage compared to other states within the US8 . From our Literature Review and Evidence-Based Research Review, our team was able to understand how and why the African American population is so heavily impacted by CAD: the various SDOH that affect African Americans, such as a relative lack of education, and their vulnerability to risk factors influenced by genetics and lifestyle choices. Although there are state-level initiatives within Illinois run the government and other organizations, it is imperative that more interventions are created to address the disparities that disproportionately affect the African American community.

This review analyzed over 110 existing articles through avenues such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar to determine potential connections between CAD within the U.S. and Illinois, and the African American population. Our team engaged in discussion with representatives from the American Heart Association and Heart Smart EKG to create a plan of action to combat risk factors and SDOH specific to Illinois.

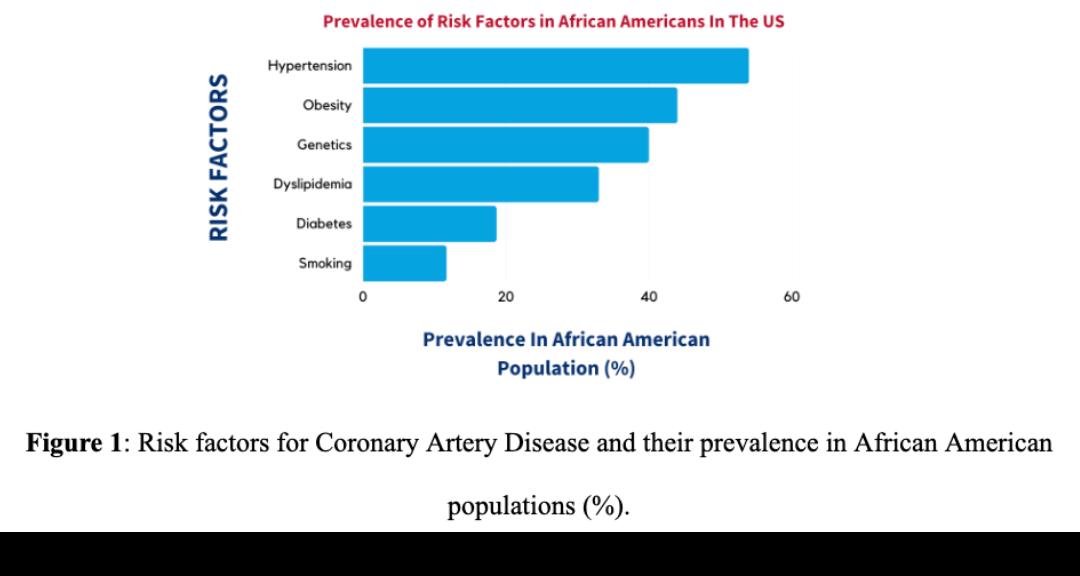

Across the United States, the African American community faces the highest rates of CAD. 20 million African American individuals in the U.S. have been diagnosed with CAD, and every year, African Americans account for 100,000 CAD deaths3. These numbers demonstrate the urgent need to address the various risk factors that contribute to these high death rates.

Genetic factors play an important role in increasing susceptibility to CAD. Certain genetic variants that increase the likelihood of dyslipidemia (high levels of cholesterol or fats) and hypertension (high blood pressure) are more prevalent in African American populations than other populations9. Cultural elements also factor into higher rates of CAD, such as traditional eating habits – for example, eating lots of ‘soul food’ which has high contents of fats and sugars – as well as attitudes towards exercise1.

Fortunately, the impacts can be mitigated. 90% of CAD diagnoses can be prevented through lifestyle changes such as improved nutrition and frequent exercise. But making these changes depends on knowledge of the various risk factors and how they can contribute to CAD6. A nationwide effort to spread

awareness of these risk factors would be helpful for suppressing the high levels of CAD within the African American community.

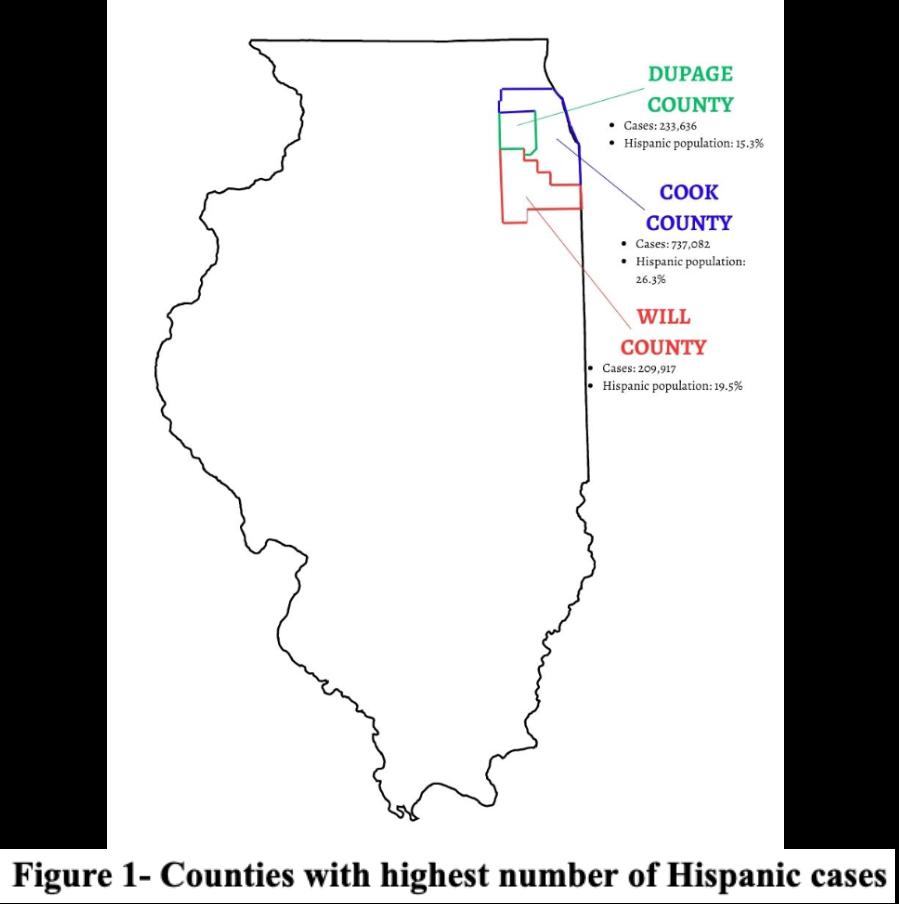

CAD trends are similar nationwide and in Illinois, the target region for our intervention, as African Americans face a 158.8% higher chance of mortality from CAD than any other race in Illinois alone7. Behind this much higher risk of mortality are various social determinants of health and risk factors present in Illinois, especially Chicago, that increase the threat of CAD.

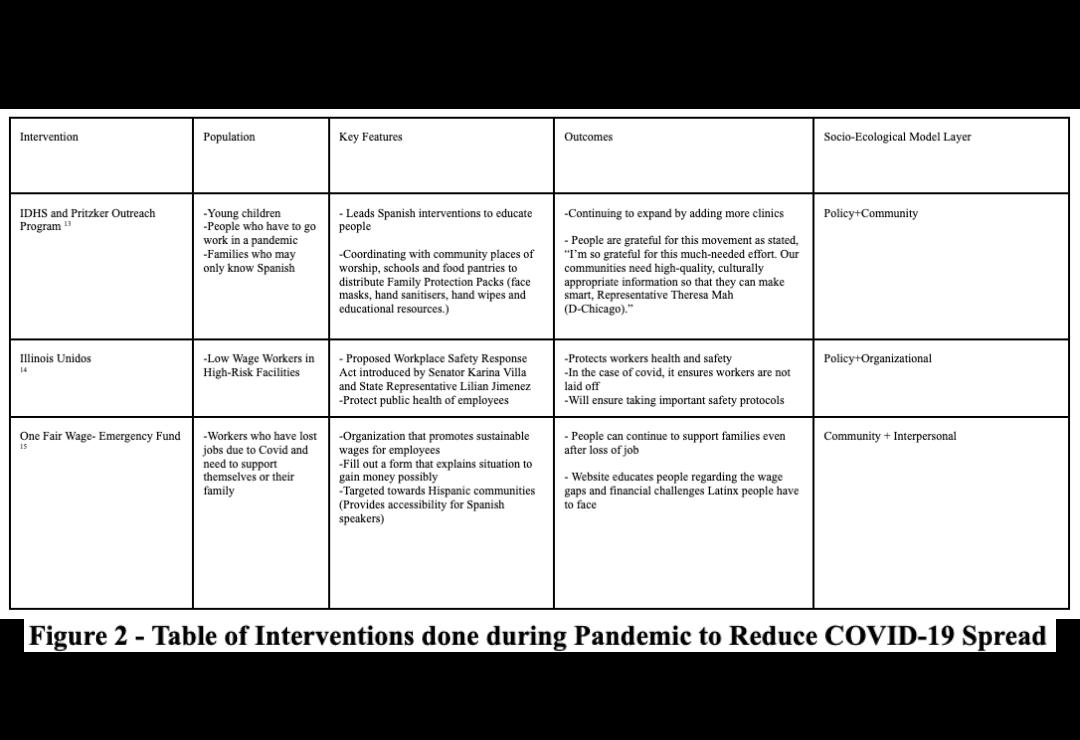

The risk factors and determinants of health that contribute to CAD in the Illinois population can be curbed through the implementation of varying types of interventions. There have been numerous cardiovascular health interventions undertaken already in Illinois that apply to the levels of the socioecological model, which represents the various individual and environmental factors that determine an individual’s lifestyle and wellbeing. These include cardiovascular health lifestyle improvement programs, patient-provider communication improvement programs, awareness events, and governmental policies.

However, many interventions, especially lifestyle programs that involve a large time commitment, can be inaccessible to certain populations. There is currently no way to ensure a long-term positive impact on CAD risk for individuals in these populations. This motivated our team to reach out to stakeholders to further investigate gaps in CAD interventions in Illinois.

We had the great opportunity of interviewing Kathy Aykroid, the director of the Max Schewitz Heart Smart Foundation, as well as Mya Gamble from the American Heart Association. Drawing on their experience with interventions for CAD, they shared some key considerations that helped us plan our own interventions. First, while most individuals do know what CAD is, they do not believe that it will affect them unless they have a direct connection to someone affected by the disease and see its implications in person. This means that programs that educate about the risks of CAD are much needed. For many populations, various intervention efforts and programs can be inaccessible due to the time commitment, transportation, or cost. Furthermore, many existing interventions lack consistent, long-term monitoring of participants, which is necessary for ensuring that participants see long-term reductions in CAD risk. We hope to address these concerns with our own intervention plans for improving cardiovascular health.

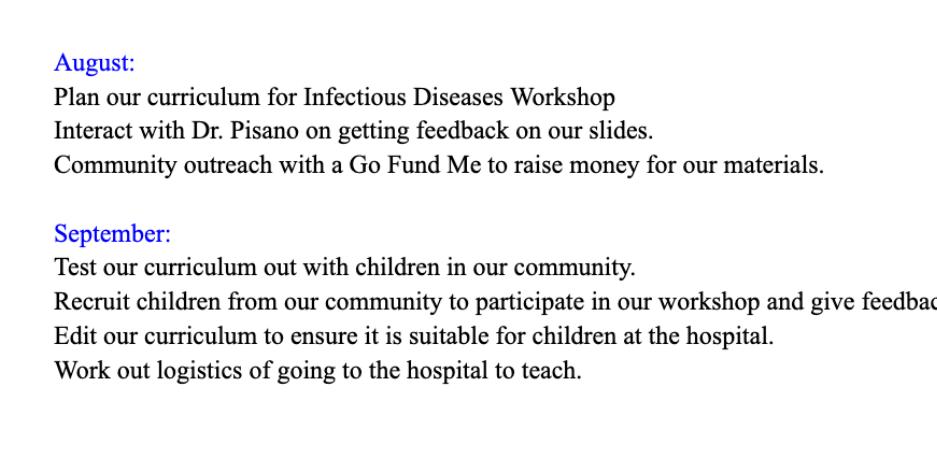

Our interventions are strategically designed to be implemented at the different levels of the socioecological model and incorporate stakeholder insights. For our first intervention, we will host workshops in the Chicagoland area to promote health literacy at the organizational level. Our primary goal in the shortterm is to target local elementary schools and plan engaging activities that educate students on CAD from a young age. In the month of August, we will run our first pilot curriculum at Highland Park Montessori.

As we understand the importance of education through our research, we hope to implement these prevention measures in children at a young age. In the month of October, we will continue to revise our curriculum through workshops in local schools, until we are confident it can excel at the community level.

Once this is accomplished, we will begin hosting workshops in community centers of downtown Chicago in November and December, specifically targeting African American communities. We will provide stations that teach attendees the importance of diet, exercise, and other health factors.

Understanding that many individuals lack a personal connection to CAD, we will have several professionals leading our sessions to build credibility. Through collaboration with our stakeholders like the American Heart Association, we will provide kiosks that offer blood pressure monitoring tools. As most existing CAD interventions are short-term and fail to follow up with communities, we have decided to implement a second intervention to combat this issue.

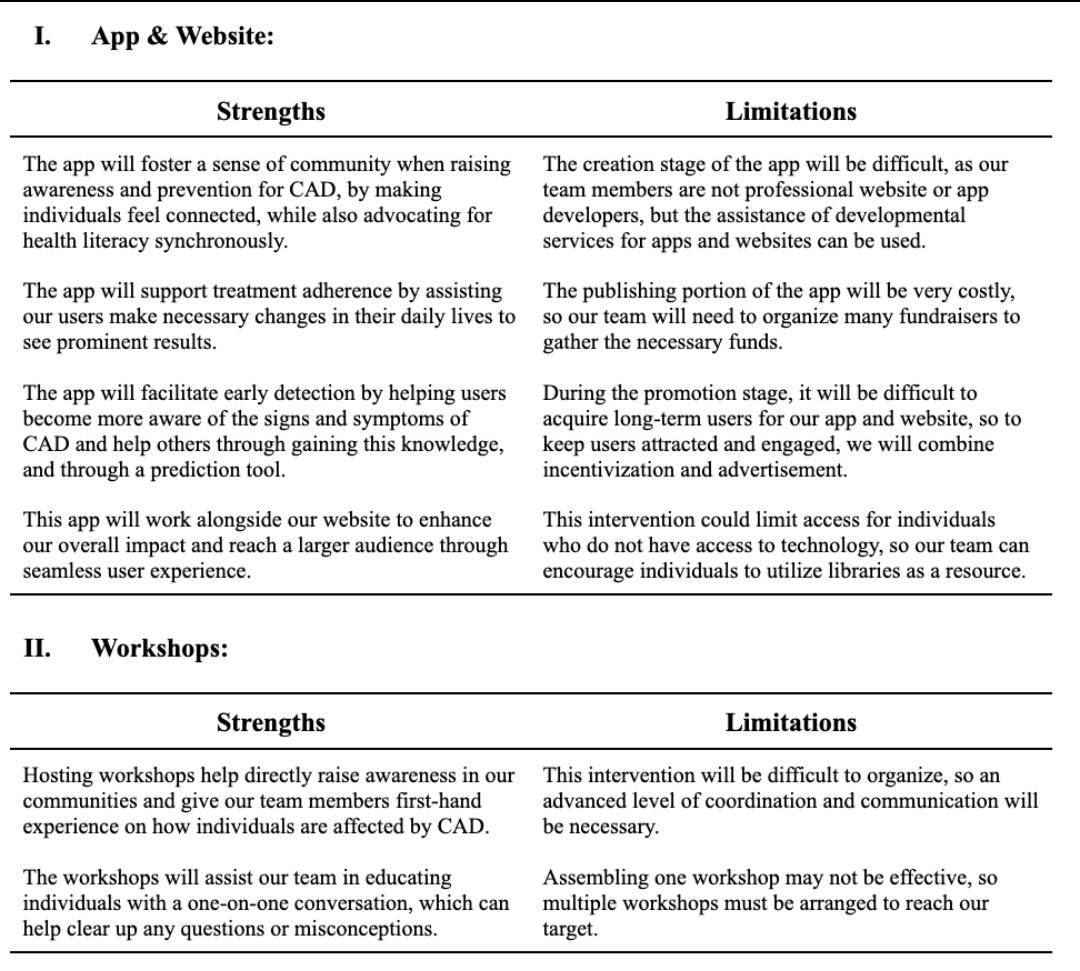

Our second intervention focuses on digital health and utilizing technology for long-term prevention. We will be creating an app and website that offer educational content on CAD detection. The app will contain tools that track vital signs, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and cholesterol levels. Additionally, it will offer personalized risk assessments based on user data to encourage individuals to seek medical attention if their risk profile suggests potential issues.

Since we know long-term adherence for individuals will be a challenge, through our app we hope to ensure individuals make long term lifestyle changes. Every attendee will have a full lifestyle plan easily accessible in the app.

For a variety of reasons – including a comparative lack of access to CAD treatment and educational resources – African Americans are predisposed to CAD at levels far higher than the general population and experience much higher mortality rates.

This inequity poses dangerous implications for both the state of Illinois and the nation at large. With a history of discrimination and racism, it is essential to provide adequate care to help promote health equity today. Our intervention strategically takes into account the social determinants of health at play in Illinois, and current gaps in care. As we have learned from our stakeholders, existing interventions lack longevity, which is why we have implemented an app and website to work in conjunction with our workshops. This way, attendees can follow up and track their progress easily.