“JAIL AND BAIL” CAMPAIGNS DISABILITY

In 1989, country music superstar Johnny Cash was “‘arrested’ for crimes against fashion,”(1) according to a short article by William C Trott. Trott wrote that Cash “was tossed into a temporary jail at the Hendersonville, Tenn., High School as part of a weeklong 'jailathon' to raise money for the American Cancer society.” In order to help ‘free’ Cash, community members including some of his famous friends like Willie Nelson donated to ‘bail him out’. By the end of the evening, the ‘bail’ raised was over $20,000.

Johnny Cash is one of my favorite artists and I always admired his advocacy work on behalf of incarcerated people. In fact, a few years ago, I co-produced with my friend Sam Love, a two-part podcast on that work. I wish that Cash were still alive so I could ask him why he participated in the jail-a-thon fundraiser.

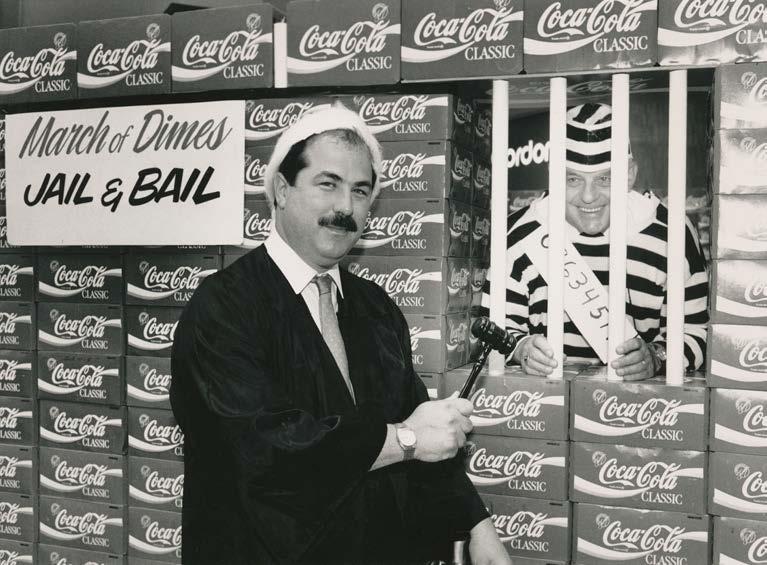

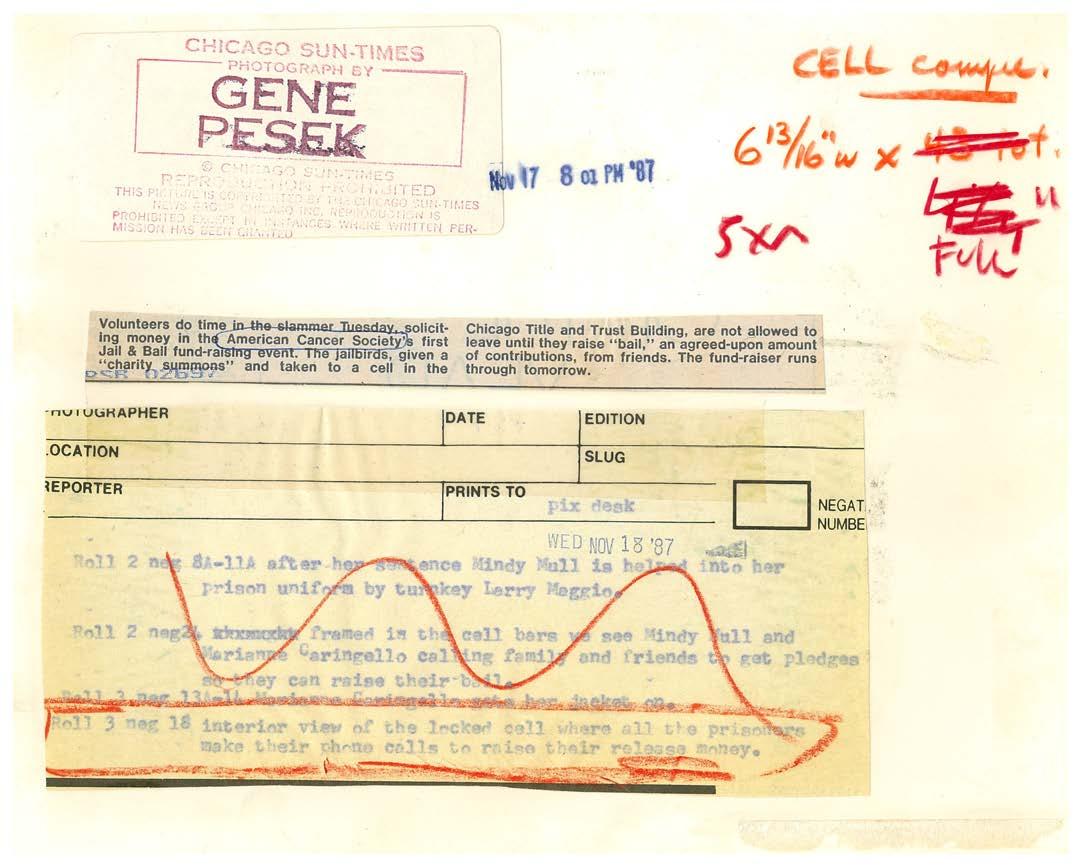

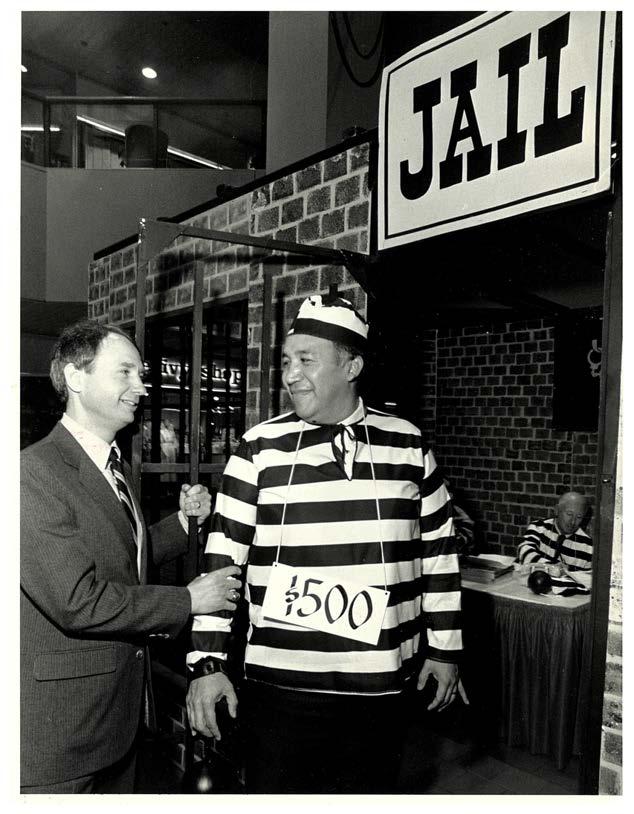

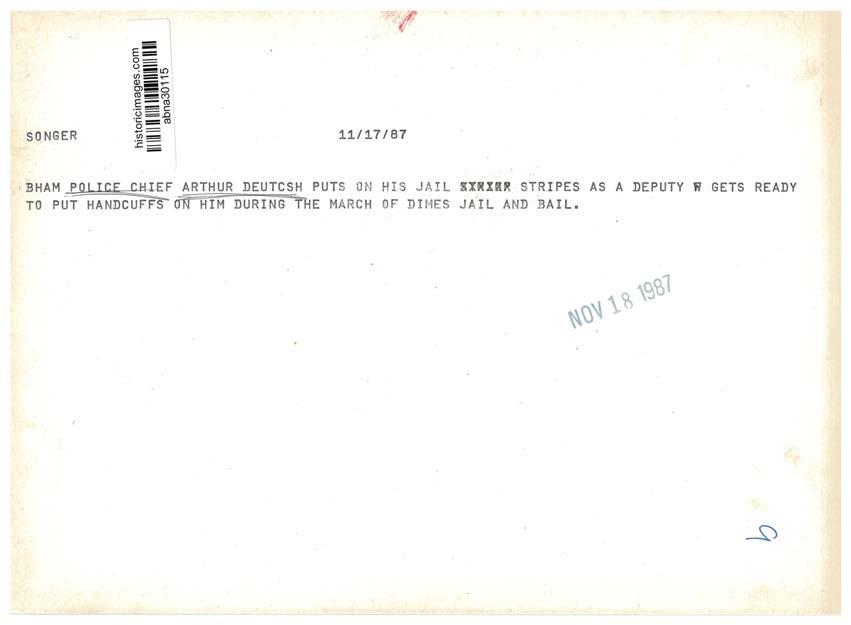

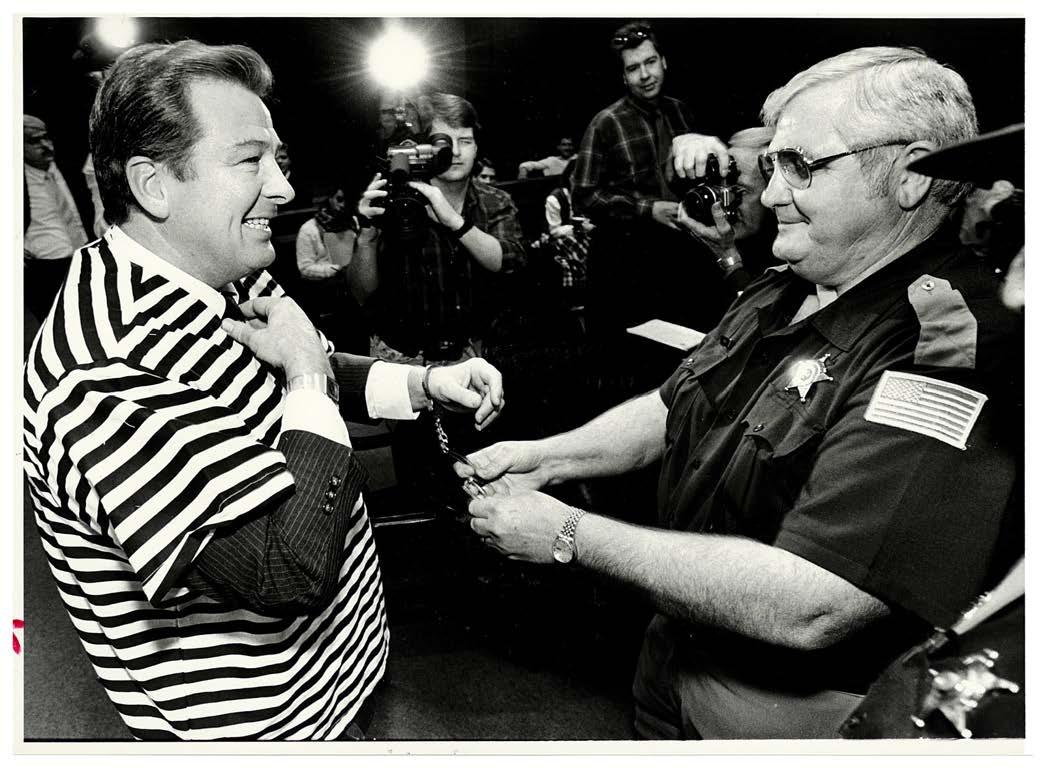

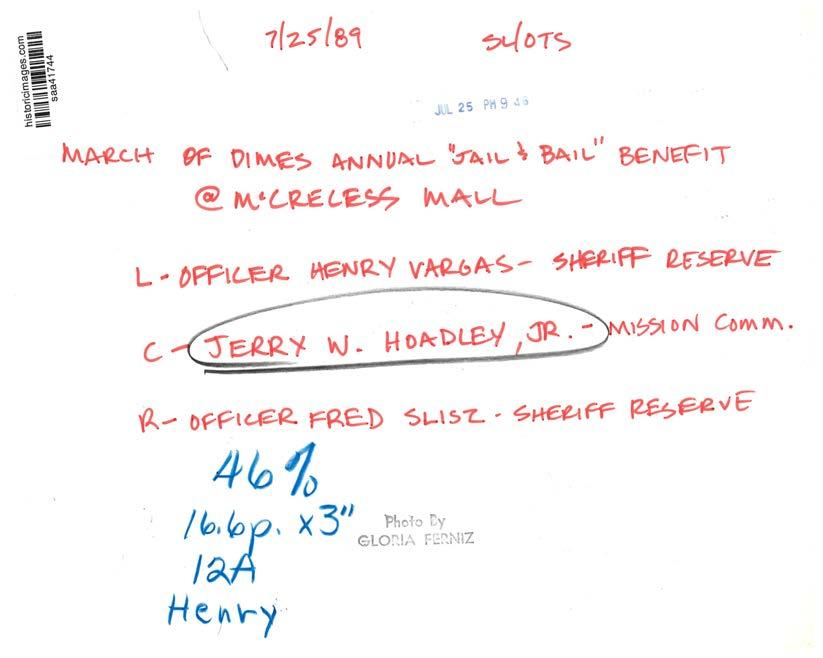

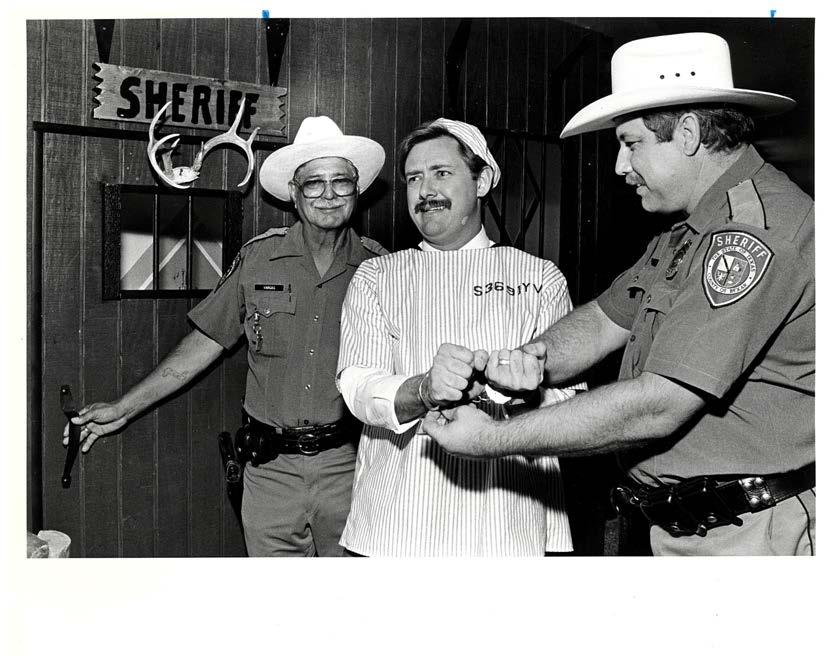

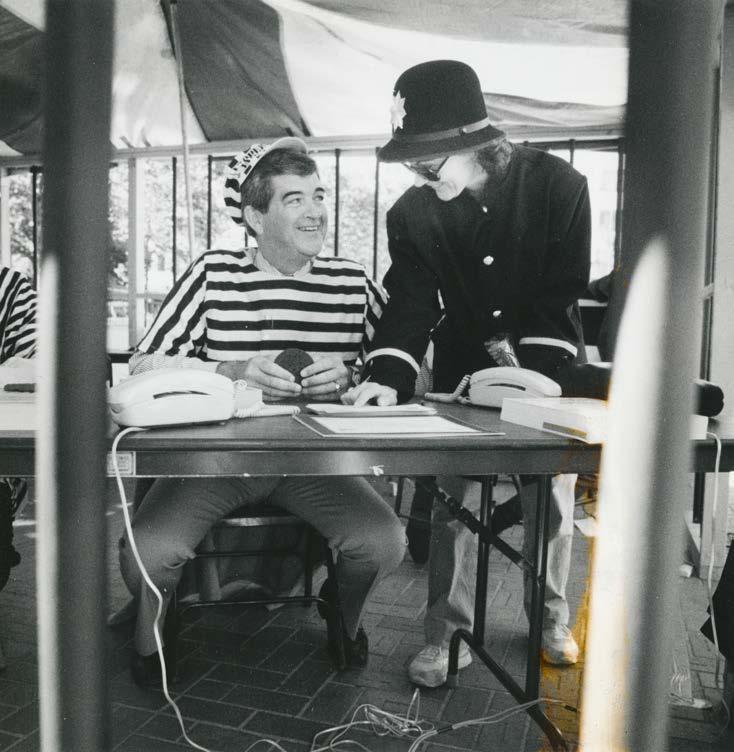

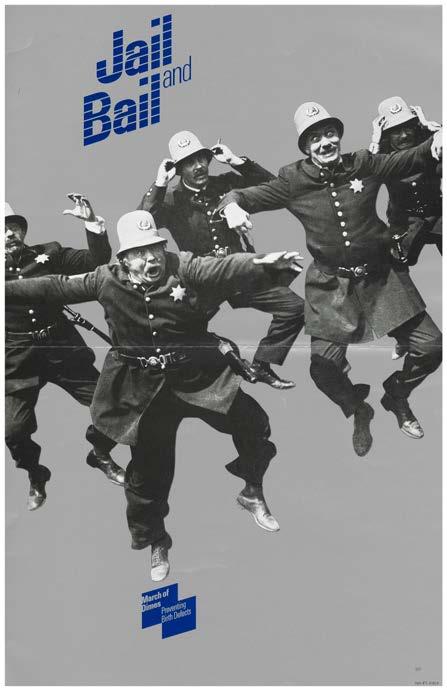

I don’t remember when I started to collect vintage press photos depicting jail-a-thons but it’s been many years. Jail-A-Thons(2) are community fundraisers that are popular with nonprofit organizations like the American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, Muscular Dystrophy Association, United Way, YMCA. local schools, colleges and more(3). Government entities such as Sheriff’s offices have also organized jail-a-thon events. These events seem to have originated with the March of Dimes in the 1950s and appear to be most popular with health and disability focused organizations.

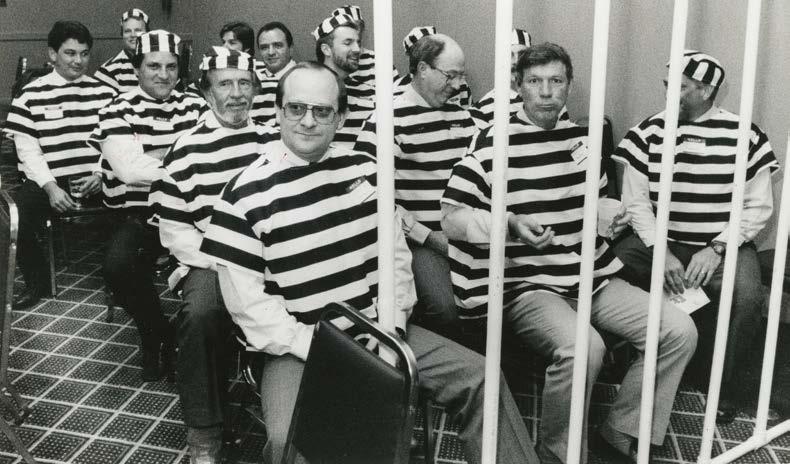

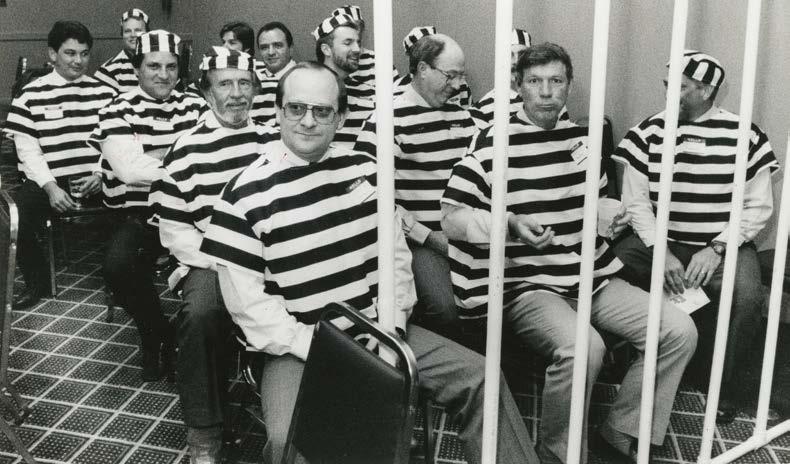

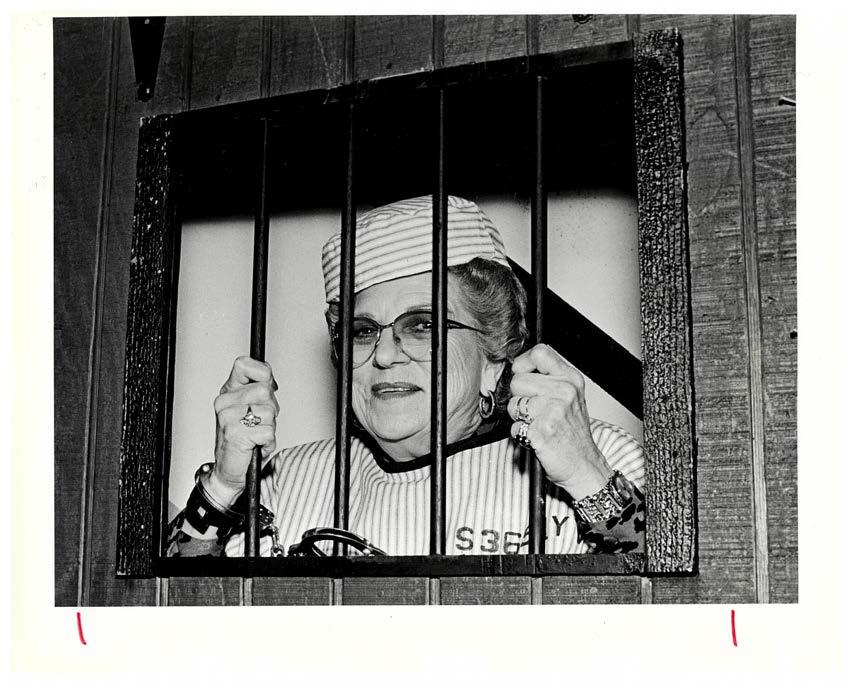

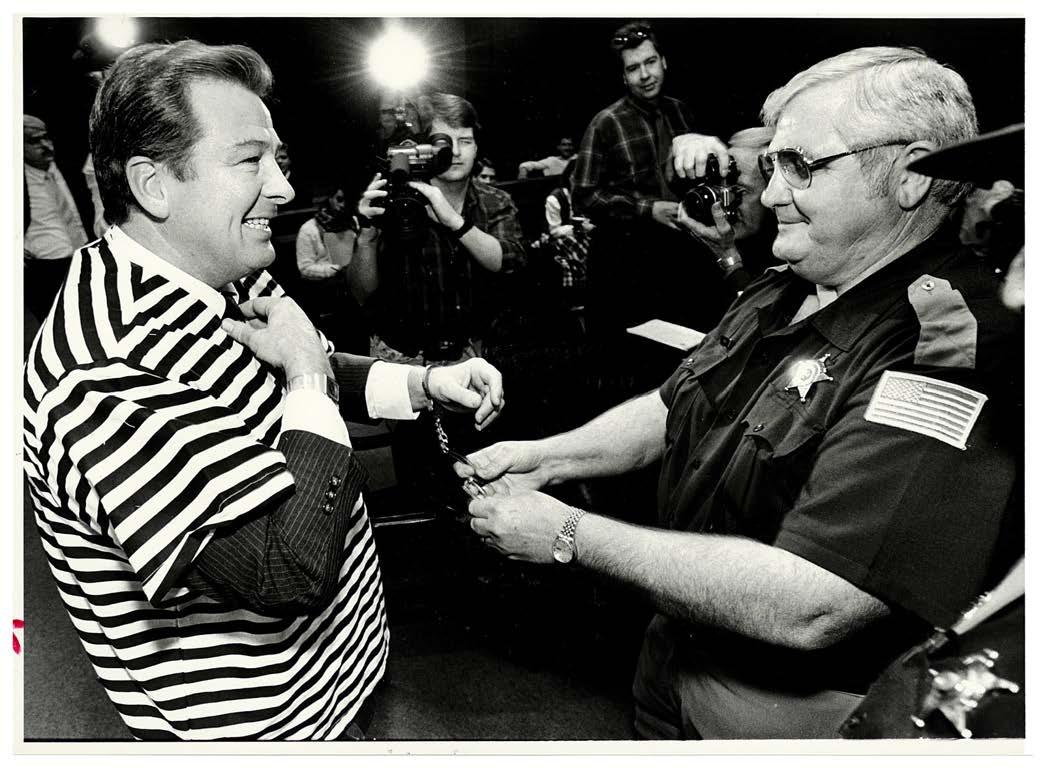

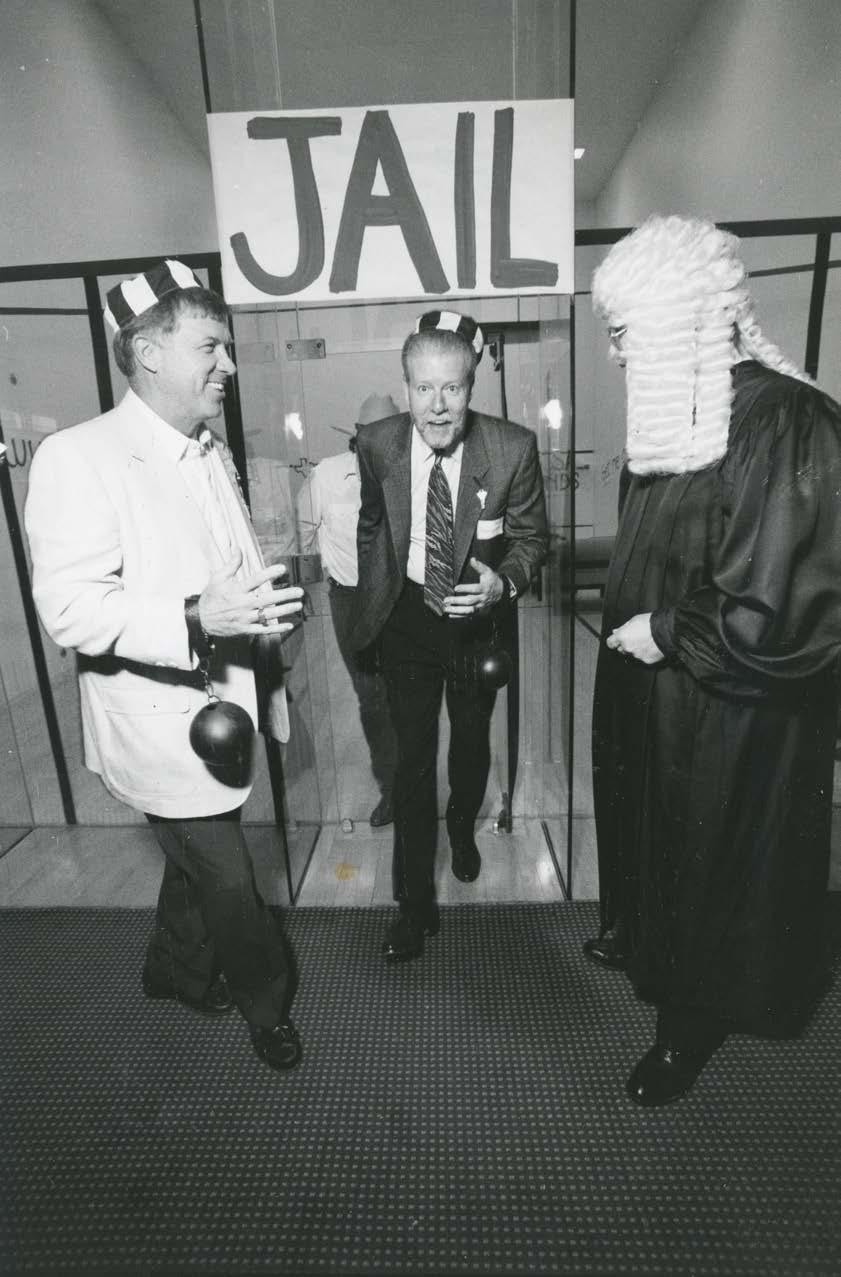

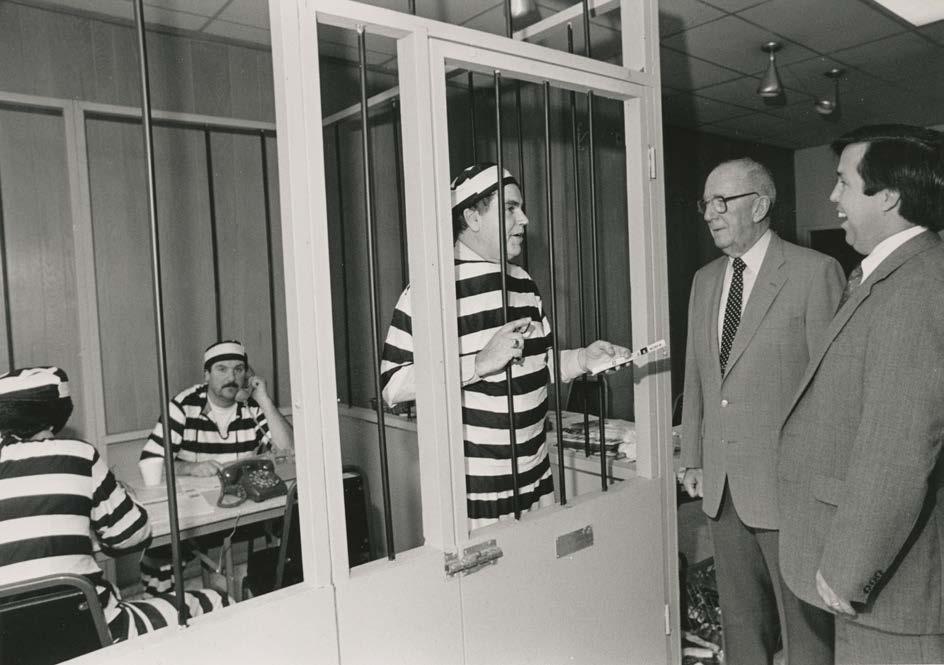

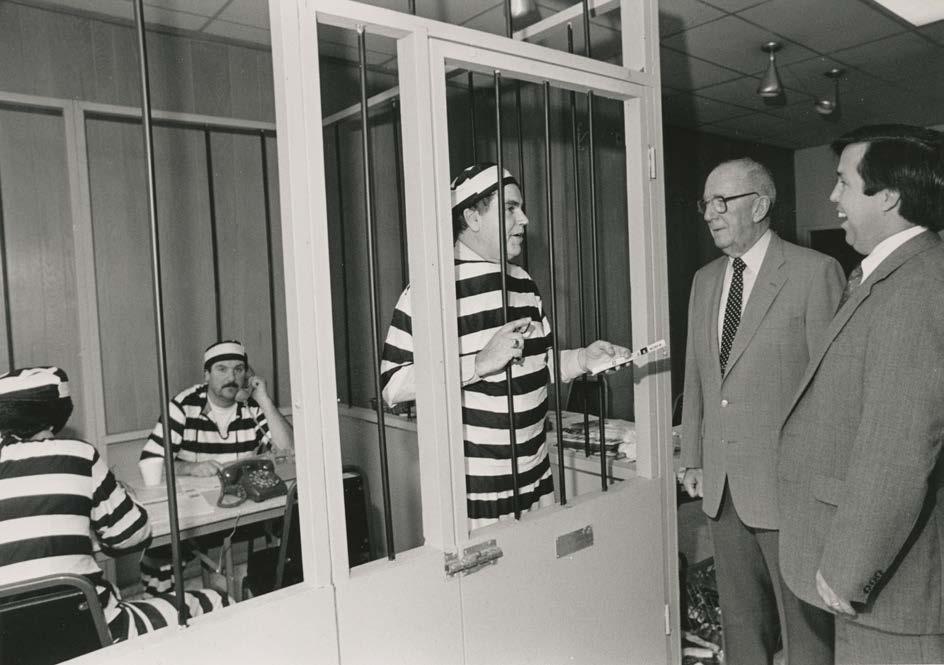

As the years have gone by, my collection of photographs has grown(4). I’ve been challenged by them in multiple ways. I find the dramatization of the pain and violence of incarceration for funds and for laughs to be repellant. These events speak to the normalization of punishment in the United States. Participants get dressed up in costumes that are replicas of prison and police uniforms, and judges’ robes. They then ‘perform’ punishment. The photos often show people laughing or putting on exaggerated sad looks. There are handcuffs and fake guns. What does all of this mean? What can we learn from these events about how our society views incarceration and punishment? I think a lot.

I decided to make something using the photos as a way to invite others into considering these issues. I thought that Dr. Liat Ben Moshe would be an ideal person to help contextualize these events and to illuminate the connections between incarceration and disability. Liat is well-respected as an abolitionist scholar of the carceral state and disability. When she agreed to write something, I was elated. Next I reached out to Sarah Warmker to design the zine. She did a beautiful job. I am also grateful to Eric Ritskes who offered valuable edits.

As you read through this zine, I hope you’ll think about who benefits from jail-a-thons and who is harmed by them. Are these lighthearted events or are they cruel performances & reenactments of pain and violence? How do these events help to obscure the central role that disability plays in the carceral state?

Jail-a-thons continue to be organized by various groups across the country. I would like it if these events would be discontinued. Incarceration is deadly serious. There was never a good time for these spectacles of violence and the time has long since passed to end jail-a-thons. Surely there are less offensive ways to raise money for cancer research.

1. William C. Trott, “Cash ‘Arrested,’” United Press International, June 5, 1987. “Cash ‘Arrested’”. United Press International, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/06/05/CASHARRESTED/8706549864000/.

2. Also called bail-a-thons, jail n bail, or jail no bail

3.Sandra R. Gregg, “Going to Jail for a Good Cause P.G.,” The Washington Post, May 11, 1985, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1985/05/11/going-tojail-for-a-good-cause-pg/7737e458-69e9-48a0-984f-3b746661eac5/.

BY LIAT BEN-MOSHE

BY LIAT BEN-MOSHE

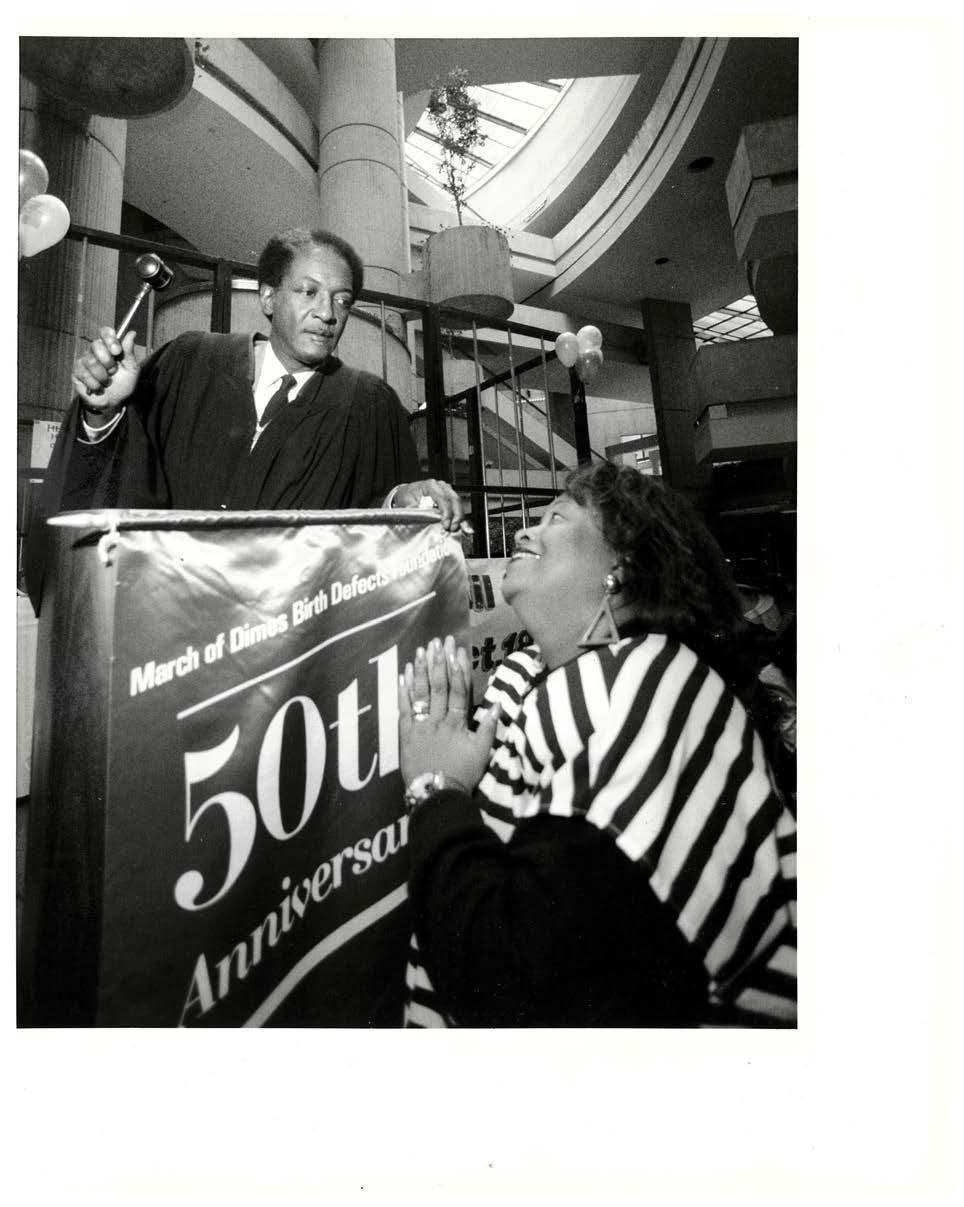

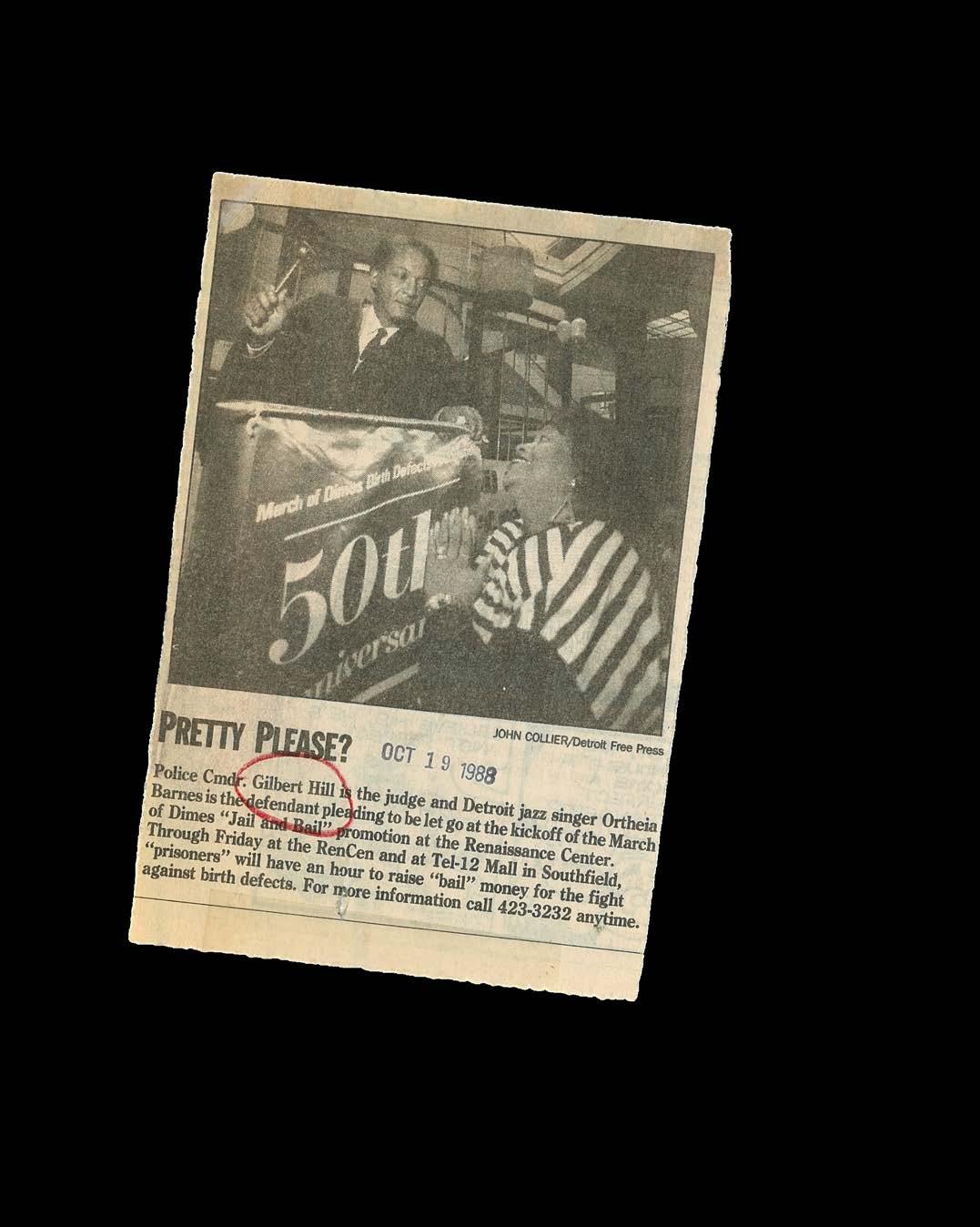

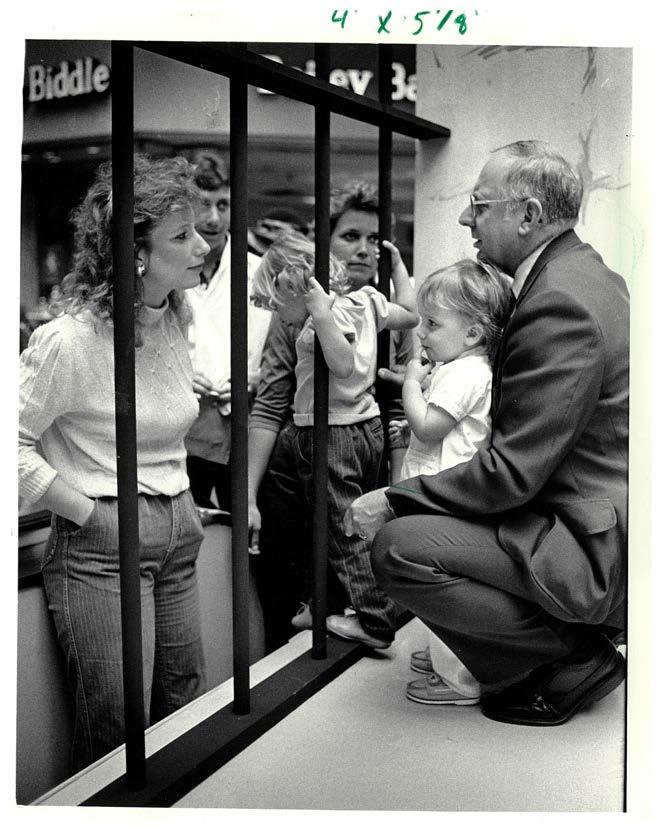

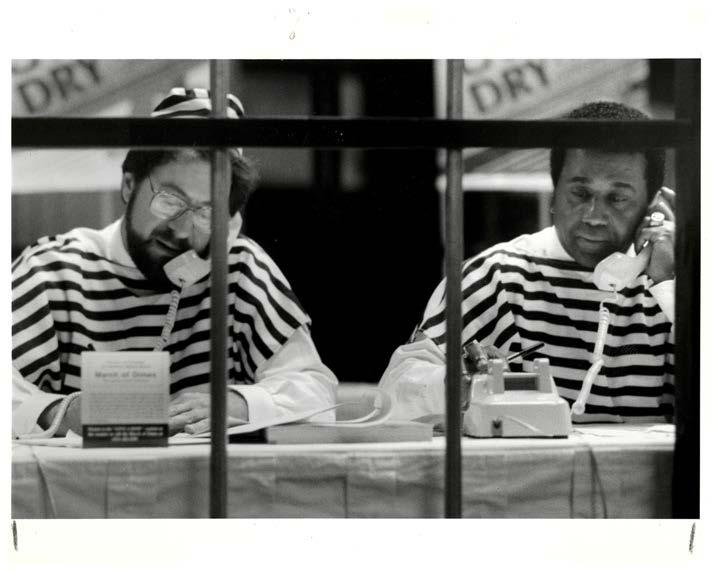

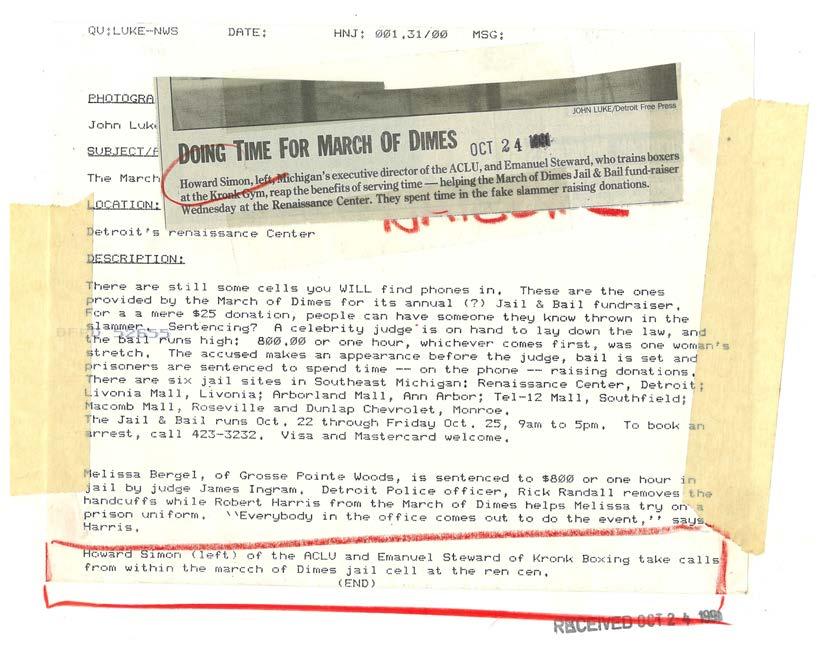

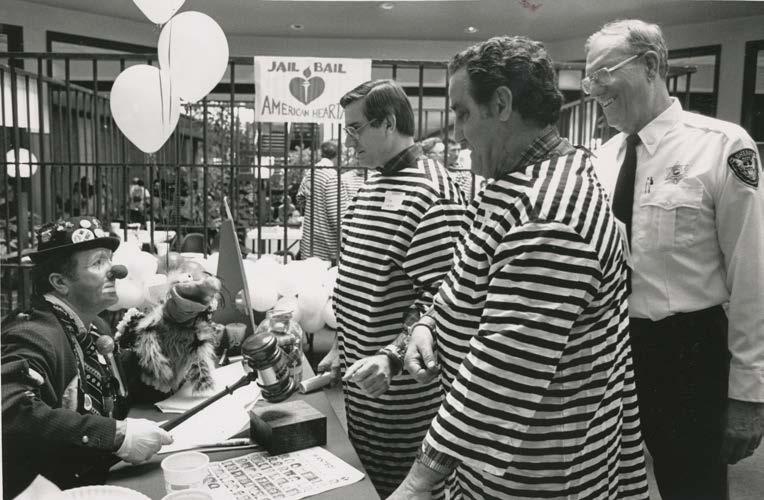

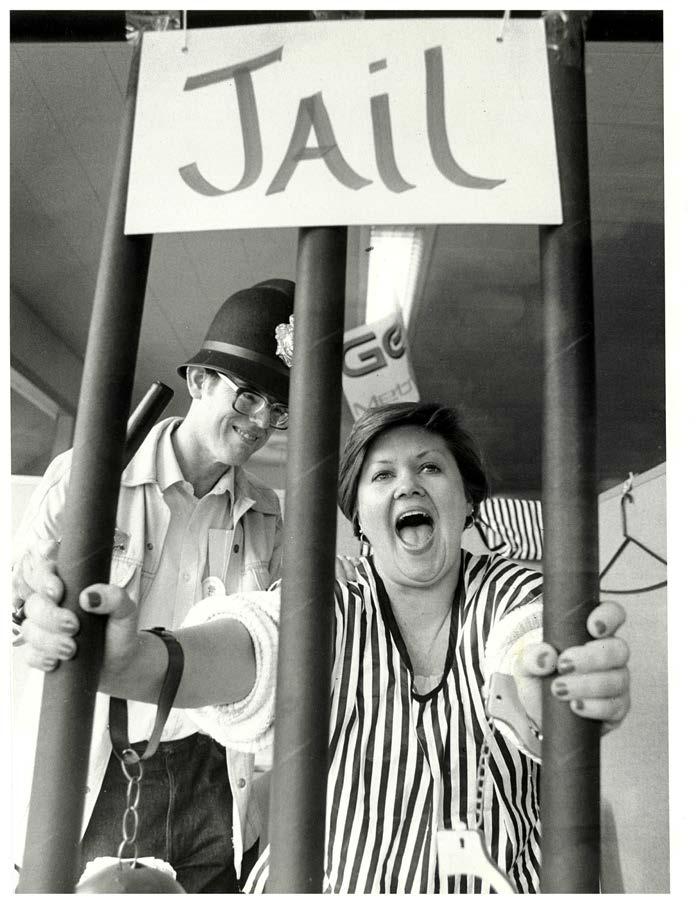

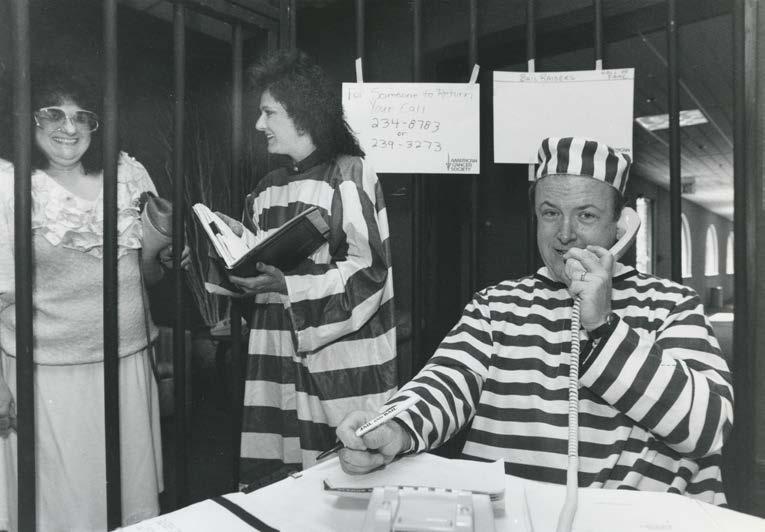

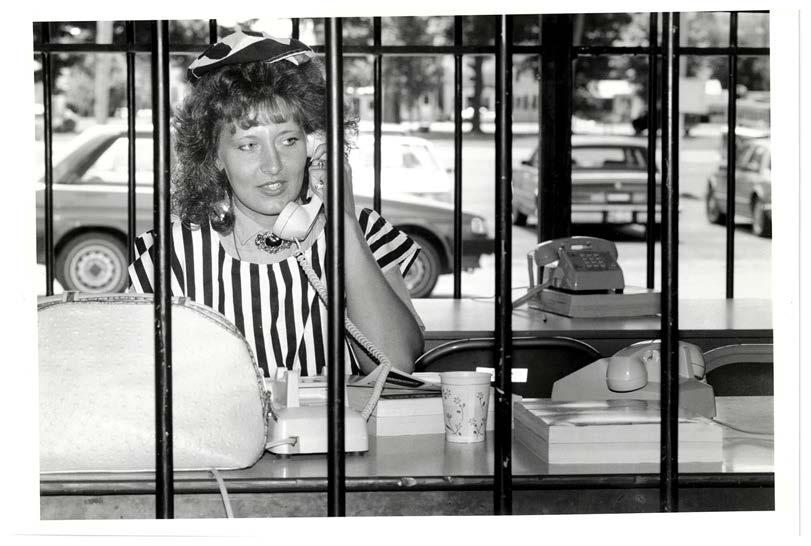

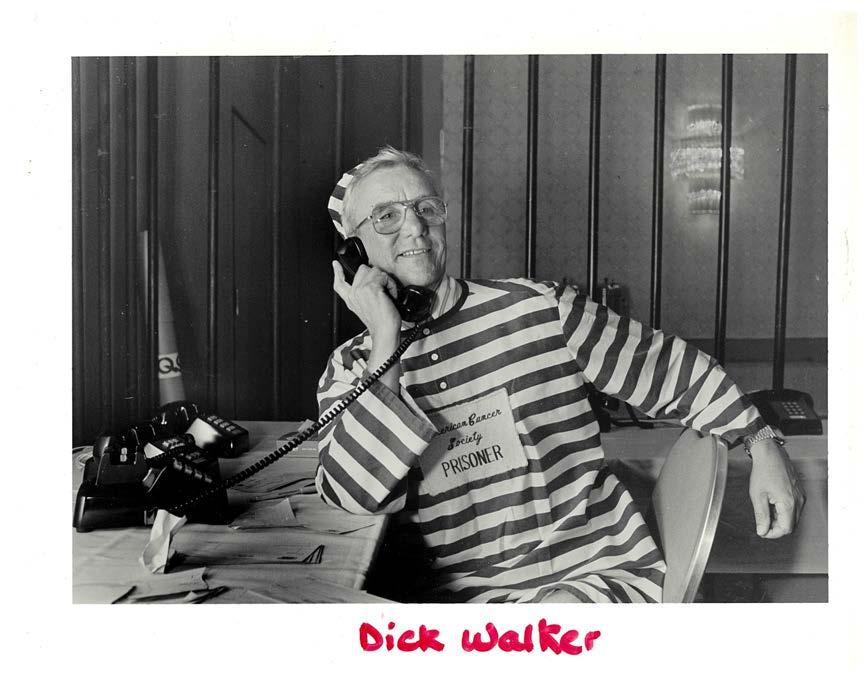

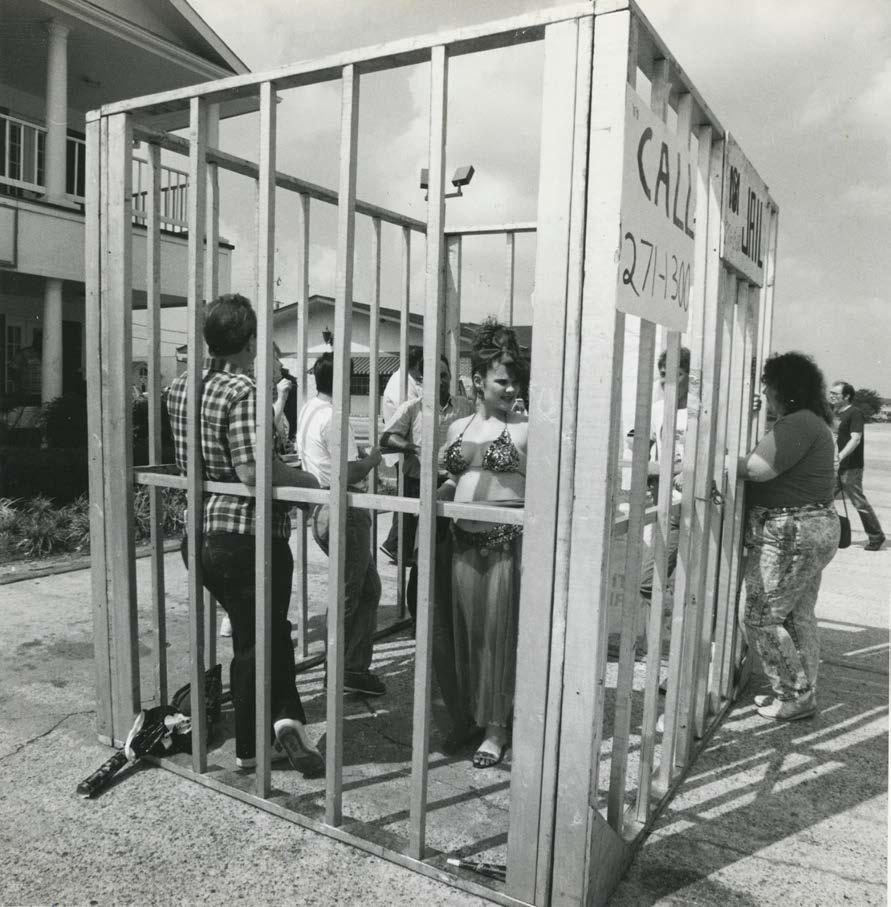

In one picture, a well-groomed white woman in a dress grabs the bars of the fake prison cell, smiling widely and laughing, while beside her, dressed in the caricature of a British ‘bobby’ (policeman) complete with toy ‘billy’ club, a white man, also smiling and in on the charade, stands guard. In other pictures, smiling people place calls on phones, often from within fake cells or while wearing stereotypical black and white striped ‘prison garb’. In another picture, a small boy ‘escapes’ from a crib/ prison-like enclosure, declaring “Your dimes did this for me!”

Many of the descriptions and write ups about the pictures note the ‘fun’ that was had or the briefness of the ‘stay’.

These images are from popular “jail and bail” or jail-a-thon campaigns, fundraising efforts most often organized by wellknown charities like The March of Dimes and the American Cancer Society. In these campaigns, local people are ‘jailed’ until they can raise enough funds to free themselves, calling their friends and families to donate money to raise their ‘bail’. The money that is raised for this ‘bail’ is then donated to the charities. Because these two charities are well regarded disability and medical related charities, through these campaigns there is a direct connection made between disability, medicalization, and incarceration, as well as a direct connection between disability and confinement/punishment. This is the problem that I want to focus on, especially the ways these fundraisers obscure the connections between incarceration, disability, and medicalization.

The first problem with such campaigns is that they turn criminalization and incarceration into a spectacle, a fun event easily concluded with a fake ‘bail’, downplaying the violence of incarceration and obscuring the connection between jail and medicalization and/or disablement. These campaigns use incarceration metaphorically through mock ‘jails’ and the made up ‘bails’ but for many people, including disabled people, incarceration is not a metaphor but a violent reality. We cannot understand disability without understanding the ways that disabled people are incarcerated.

Unfortunately, while reliable data on the numbers of disabled or chronically ill people who are incarcerated remains elusive, perhaps intentionally, it is clear that people with a variety of disabilities and illnesses are ‘represented’ and over represented in prisons and jails.

Incarceration is central to the experience of disabled people, whether through the very real experience of confinement through prison, but also through separation and confinement into special schools, hospitals, psychiatric facilities, nursing homes, or through the looming “institution yet to come” that exists as a presence in the lives of all people with disabilities, even those who are not (yet) captured in them. This is especially true for marginalized populations such as those experiencing poverty, Black and Indigenous people, youth, women, LGBTQ2S people, etc(1).

The flip side to the above is that disability is central to understandings of incarceration. These “jail and bail” theatrics obscure both the presence (and over representation) of disabled people within prisons, but also the disabling nature of prisons themselves.

Beyond representation within prisons, the disabling nature of incarceration and whose bodies are available for capture should be understood as a core feature of incarceration(2).

“Jail and bail” campaigns obscure how disabled people are captured within prisons at a high rate, while also making a mockery of what these prisons do to those within them. Prisons are themselves disabling environments.

If one wants to cure or alleviate cancer, like the American Cancer Society purports, there is a real (and not metaphoric) connection between imprisonment and cancer. For example, in 2014, a report titled “No Escape”(3) outlined the health issues people were experiencing in Fayette prison, a prison that was built on a coalrefuse site in the town of La Belle, Pennsylvania. These included skin conditions, throat and respiratory illnesses, thyroid issues, and tumors. According to the report, 11 of the 17 prisoners who died at Fayette between 2010 and 2013 passed away from cancer(4). It is no accident that as La Belle (and towns like it) face economic downturn, spurred by the decline of the coal industry, they face propositions to put these now toxic sites to use as prisons, prisons that in turn produce disabling results for those who are forced into them(5). Examples like this one are not exceptional and only one aspect of the disabling nature of prisons.

Understanding incarceration in relationship with disability also helps us understand the connections to medicalization.

Because of the disabling and illness producing methods of prisons, they were (and in some ways still are)(6) breeding grounds for medical experimentation. The most pervasive types of experimentations done in carceral settings (especially prisons) is “biomedical research, often supported or directed by federal agencies, and pharmaceutical research, largely funded and controlled by private drug companies”(7). For example, between 1960-1971 a series of radiation experiments were performed on 131 Washington and Oregon prisoners(8).

Other examples of the way that medicalization and disability are intricately intertwined with prisons include the medical (mis)treatment of imprisoned people through the intentional lack of services and medical equipment, examples of forced sterilization, mandatory medical reporting, and the participation of medical professionals in executions/lethal injections. While medicalization is often equated with a duty of care and freedom (from illness, etc.), in the context of prisons medicalization can be its own form of violence and confinement rather than care. Relatedly, medicalization for many disabled people is a form of incarceration, not the liberation from it!

Seeing and understanding all of these connections can lead us towards understanding that: working for the end of the Prison Industrial Complex is to also work towards the end of the Medical Industrial Complex, which is to also work towards the end of our normative understandings of disability.

Organizations such as the March of Dimes promote a medicalized view of disability, one in which disability is perceived as a problem or a deficit to be fixed or cured. In contrast, disability (and deaf/mad/neurodiverse) cultures understand disability not, only, as a medical condition in need of fixing but also as an identity, a political formation which can be a source of both pride and oppression.

Disability is not something in people’s bodies or minds. It is born out of interaction with one’s social and physical environments. As disabilityrights activists have been pushing for decades, including through protesting “jail and bail” campaigns and other ableist campaigns, disabled people do not want pity in the guise of help or charity - they want equality (with non-disabled peers), rights (to education, sexuality etc.) and freedom (from segregated classrooms, institutionalization etc.). They don’t want money for fixing themselves but for fixing the

Changing the way we think of disability would also help us change the ways we often use Imprisonment rhetorically to describe disabling states. The description of a wheelchair user as “being confined to a chair,” for instance, conjures up ideas of wheelchairs as imprisoning the people who utilize them. People who use wheelchairs ourselves, describe them as liberatory auxiliary aids that assist us in being more independent, not restrict us. This is the way we must reorient our thinking and our societies.

In these fake “jail and bail” campaigns, instead of raising funds for actual bails for criminalized disabled people, money goes towards a charity framework of disability. This charity frame depoliticizes disability and individualized it. It perpetuates disability or illness as personal tragedy or misfortune and does not focus on the social conditions that create impairment or disability, including their racial colonial capitalist stateinduced underpinnings (environmental toxins, lack of access to clean water, adequate nutrition, affordable housing etc.).

Justice do not see integration or acceptance as the goal but the formation of new caring, socially just communities. It is a conceptual shift from notions of advocating for rights or for people with disabilities in an unjust society to advocating for social change, in relation to the ways various oppressions, such as racism, sexism, capitalism and ableism intersect to influence the lives of disabled people, including those most marginalized(9).

This is the same conceptual shift necessary for abolition in the context of prisons: the desire for new, caring, just communities that repair harm in transformative ways. Understanding the connections between carcerality, disability, and medicalization allow us to not only see the problems with campaigns such as “jail and bail” fundraisers, but to see the ways the abolition includes the dismantling of prisons/incarceration in all forms, the end of medical harm and violence, and the reorientation of the ways we see disability as a form of imprisonment/punishment.

1. Ben-Moshe, Liat, Chris Chapman, and Allison C. Carey, eds. Disability incarcerated: Imprisonment and disability in the United States and Canada. New York: Palgrave/Springer, 2014.

2. Ben-Moshe, Liat. Decarcerating disability: Deinstitutionalization and prison abolition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

3. McDaniel et. al. 2014

https://abolitionistlawcenter.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/09/no-escape-33mb.pdf. Further discussion in Stewart and Ben-Moshe 2017

4. Liat Ben-Moshe and Jean Stewart, “Disablement, Prison and Historical Segregation: 15 Years Later,” in Ravi Malhotra and Marta Russell, eds., Disability Politics in a Global Economy: Essays in Honor of Marta Russell (London; New York: Routledge, 2017).; see also Rose Braz and Craig Gilmore, “Joining Forces: Prisons and Environmental Justice in Recent California Organizing,” Radical History Review 2006 (October 1, 2006): 95–111.

5. Schept, J. Coal, Cages, Crisis: The Rise of the Prison Economy in Central Appalachia. 2022. New York, NY: New York University Press

6. Today, more than one-third of these medical experiments take place in alternative corrections facilities such as probation, residential drug treatment programs, parole, community corrections, home confinement, and boot camps. See Appleman 2020

7. Appleman, Laura I. "The captive lab rat: human medical experimentation in the carceral state." BCL Rev. 61 (2020): 1.

8. Appleman 2020

9. Ten principles of Disability Justice: https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10principles-of-disability-justice; further resources

https://projectlets.org/disability-justice