“They Mowed Them Down Like Wheat:”1

Mariame Kaba

Mariame Kaba

Mariame Kaba

Mariame Kaba

Prisons in the United States have long been instruments of racist violence and repression. One stark example that illustrates that ugly history is the Anguilla Prison Massacre in Georgia. On July 11, 1947, Warden H. G. Worthy ordered guards to open fire on prisoners at Anguilla. They murdered eight men.

The warden claimed the prisoners were trying to escape, but investigations— first by the NAACP and then by the Federal government—suggested that law enforcement’s story was a lie, and that the warden’s actions were vindictive and racist.

Law enforcement officials were indicted, but the all-white jury refused to convict them. White Georgians intended for prisons to violently discipline Black people; the guards, from that perspective, had done their job of enforcing white supremacy. The Anguilla Prison Massacre highlights how prisons were a central institution for enforcing white dominance under Jim Crow—and urgently reminds us that they remain so today.

Glynn County prison camp after guards open fire on prisoners, Brunswick, Georgia, July 11, 1947.2

The Anguilla Prison Massacre was perpetrated amid an ongoing struggle for Black civil rights in Georgia. In the years following the Civil War, Black men had at least limited voting rights in Georgia, and 58 Black representatives served in the State legislature.3 In 1908, however, Georgia amended its Constitution in order to disenfranchise Black voters, joining most of its Southern neighbors in adopting poll taxes, literacy tests, and other measures which blocked Black people from the ballot.

Black activists spent the next decades attempting to restore Black voting rights in the teeth of Jim Crow. The participation of Black soldiers in World War II helped buttress popular support for voting rights. The Gainesville, GA Eagle, for example, wrote that Black voters were “entitled to the ballot” because of their “defense of the nation” in World War I and II. “If they can fight for freedom over there,” the paper argued, “they certainly should be allowed to vote for it here.”4

Black voters across the country won a major victory on April 3, 1944, when the United States Supreme Court struck down the Texas Democratic Party’s policy of running whites-only primary elections in Smith v. Allwright. However, these gestures towards progress also prompted white backlash. The disenfranchisement of Black voters had allowed Georgia’s Democratic Party to dominate state elections, and they were not going to give up that power without a fight. Republicans relied on Black votes, and the state party collapsed without them in the late 19th century. A month after the Smith v. Allwright verdict was issued, a representative of Georgia’s Democratic Executive Committee insisted “our primaries are a function of the Democratic Party and we say who can and who cannot vote.”5 Because Smith v. Allwright was about Texas elections, the Executive Committee decided, it simply “did not apply” in Georgia.6 In 1945, however, just months after the state legislature

and liberal Democratic Governor Ellis Arnall abolished the poll tax, a U.S. District Court affirmed Smith and ended Georgia’s whites-only primary.

His outrage over Smith v. Allwright led Eugene Talmadge, the state’s governor from 1933-37 and 1941-43, to run for another term in 1946 on a virulently

segregationist platform, promising to restore the whites-only primary and to defend white supremacy. “THIS IS A WHITE MAN’S COUNTRY AND WE MUST KEEP IT SO!” he declared.7

The 1946 Georgia gubernatorial race thus became a struggle for Black rights against the persistence of white supremacy. Black veteran families and civic organizations, including Atlanta chapters of both the Negro Voters League and the Urban League, organized voter registration drives in large cities and rural areas across the state. Volunteers distributed

50,000 leaflets and offered rides to registrants. Over the course of two months, volunteers registered 18,000 Black voters in Atlanta. In just seventeen days, organizers in Savannah registered over 12,000 Black voters, bringing the city’s total to over 20,000.8

The forces of white supremacy were also organizing, though. For months, registrars across the state had made concerted efforts to challenge the eligibility of Black voters in their counties.9 Talmadge supporters submitted claims to disqualify Black registered voters on flimsy pretenses.10 In the months leading up to the election, The Statesman, Talmadge’s weekly newspaper, published several articles encouraging readers to disqualify Black registrants and equipping them with the information needed to do so:

If the white citizens of the state will wake up . . . they can disqualify and mark off the voters’ list three-fourths of the Negro vote in the state . . . If the list is purged in your county, you will find many Negroes could be stricken off because they have been convicted of a felony [or based] on residency requirements.11

Authorities barred approximately 16,000 Black voters from voting during the primary in the 1946 Georgia governor’s race.12 In contrast, they struck only 450 white voters from the rolls.13 In some Georgia counties, no white voters were challenged. In several counties, a challenge was brought against every single Black registered voter. What’s more, in the days leading up to the primary, several Black churches in

Fitzgerald County received warning notices on their doors: “The first Negro to vote in the White Primary in Fitzgerald, July 17, will never vote again.”

There were some white people who opposed Black disenfranchisement. Some felt it was inequitable; others believed open racism reflected poorly on the state; still others thought their own political fortunes depended on Black voters. Whatever their motivations, a few voting registrars opposed to the discriminatory practices reported them to U.S. district attorneys or resigned. Some local newspapers reported on the illegal efforts to push voters off the rolls.14

When Atlanta mayor Hovis Floyd discovered that someone had leaked

addresses and other confidential information to facilitate the disqualification of Black voters, he became distressed. Floyd requested a federal investigation. The FBI subsequently found evidence of statewide efforts to disqualify or intimidate almost 50,000 Black voters. It is some of the most comprehensive evidence of racist voter suppression collected in the U.S. to this day.15

The scandal did harm Talmadge, who lost the popular vote. But the County Unit System in Georgia operated in a way that gave equal weight to all counties in the vote. This empowered white rural voters in sparsely populated counties, and their support won Talmadge the Democratic primary.

White supremacists wasted no time in consolidating their victory by targeting Black voters with violence. On the day after the primary, someone shot and killed Maceo Snipes, a WWII veteran and the only Black person to cast a vote in Taylor County, on the porch of his mother’s home.16 They charged Edward “Cooper” Williamson with the murder but exonerated him a week later, determining his actions to be “self-defense.”17

White jurors exonerated Williamson on July 25th. On that same day, Georgia reaffirmed its commitment to white supremacist violence with one of the worst mass lynchings of the era. A Walton County mob of around thirty armed, unmasked men stopped a car carrying two Black couples: Dorothy Dorsey Malcom and Roger Malcom and Mea Murray Dorsey and George Dorsey. People had accused Roger Malcom, a World War II veteran, of stabbing a white farmer.18 His wife and in-laws had picked him up from jail and were driving home when they were stopped. The mob shot the four victims over 60 times. The incident became known as the Moore’s Ford Bridge lynchings.19

The spectacular violence galvanized protests across the country. Demonstrators gathered daily in Washington DC. Black publications—including the Atlanta Daily World, the Savannah Tribune, and The Crisis—condemned and reported on the lynchings. The NAACP offered a reward of $10,000 for information leading to an arrest. The National Maritime Union also offered a $5,000 reward in honor of the

6,000 Black sailors who died during World War II.20

Other local organizations and state officials contributed too. A delegation from the United Negro and Allied Veterans of America visited Walton County to highlight the violence Black veterans experienced after WWII. Attorney General Tom Clark announced the FBI would start a federal investigation.

Investigations were hampered though, because, as an article in The Nation put it, the lynchings were a community crime “and the criminals are protected by the fears and prejudices of their fellow citizens.”21 In interviews with The New Republic, Walton County locals openly threatened anyone who might offer information about the murders. Such witnesses, they said, would “never live to spend [the reward money].”22 Not a single perpetrator was identified. County officials were still blocking efforts to investigate the lynching in the 2020s.23

As for Eugene Talmadge, NAACP director Walter White immediately

suspected that he was involved in the lynchings, writing to U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark said that he believed the lynchings were “the direct result of []a conspiratorial campaign to violate the U.S. constitution by Eugene Talmadge and the Ku Klux Klan.”24 Indeed, FBI files later revealed that he had come to Walton County the day after Malcom was accused of the stabbing and, according to a witness, told the victim’s brother that he would give immunity to anyone “taking care of Negro.”25

Eugene Talmadge died in December 1946, before he could take office,

and the federal investigation of the election requested by Hovis Floyd petered out.26 Investigative reporters, Black and white, who wrote about the state’s discriminatory electoral practices received harassing letters and phone calls. C. E. Gregory, a political reporter for the Atlanta Journal who had investigated Talmadge, had his home bombed.27

After the tumult and hopes of 1946, the Anguilla Prison Camp Massacre was brutal evidence that white supremacy still had Georgia in its grip.

Following the Civil War, Southern states passed so-called “Black Codes” that included vagrancy laws and other measures aimed at criminalizing newly freed Black people; they also created convict leasing systems, sending the men incarcerated under these laws to work for the landowners who had once enslaved them. The prisons were thus intended to force Black people to once again labor for whites.29 By the 1940s, authorities had substituted the convict leasing system with the chain gang and the work gang, forcing prisoners to build roads instead of working for private companies. As under chattel slavery, the guards used guns and whips to threaten chained or unchained prisoners working on road crews.30

When Black prisoners protested work under exploitative conditions in prisons, whites saw it as a threat to their rule and could respond with extreme violence. That is what happened in Anguilla Prison on July 11, 1947.

According to the New York Times, a group of prisoners brought to labor on the Jesup Highway in Brunswick, Georgia “refused to work.” Brought back to camp in a caravan followed by the warden and the county police, they refused to get out of the trucks. Chief Russell B. Henderson told them to “cut out that foolishness,” and they got out and lined up in front of the barracks.

From this point, accounts of the incident diverge. The Times story, based on Warden Worthy’s testimony, claimed that the prisoners spontaneously tried to escape, diving under a barracks and then running towards a fence. It was to prevent their escape, Worthy said, that the guards opened fire, killing eight prisoners and wounding another five.

Worthy’s account shaped early news coverage. An initial grand jury investigation also took Worthy’s testimony as definitive and quickly exonerated both Worthy and five guards.

However, prisoners disputed Worthy’s account. Worthy told the grand jury that a prisoner named Willie E. Bell had tried “to charge and disarm him.”

In self-defense, Worthy claimed, he shot Bell in the leg. But Bell told a coroner’s jury a different story: he said that Worthy had targeted him.

He had been standing with the other men when Worthy “told him to step out of the group” and threatened to kill him. He refused, saying “I ain’t gonna come out because if I come out I’ll come out dead.”31 Worthy, Bell said, was “half drunk” and “wanted to kill me.” Another incarcerated man, Charlie Veal, affirmed that Worthy had said “Come out, Pee Wee, I want to kill you.”32

Worthy then “reeled into the packed prisoners” with his handgun and shot Bell in the leg, reportedly yelling “Let ’em have it!”33 The prison guards—and, according to the survivors, Chief Henderson and two county police officers—opened fire on the group, sending the incarcerated men scrambling for cover. All of this took, perhaps, one minute.34

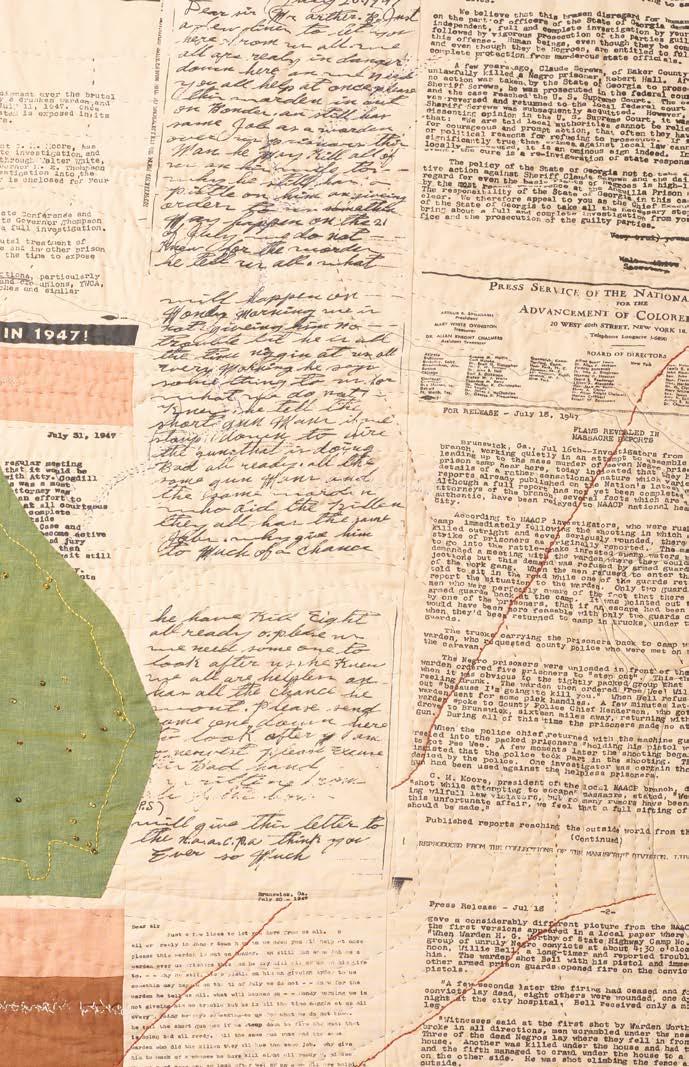

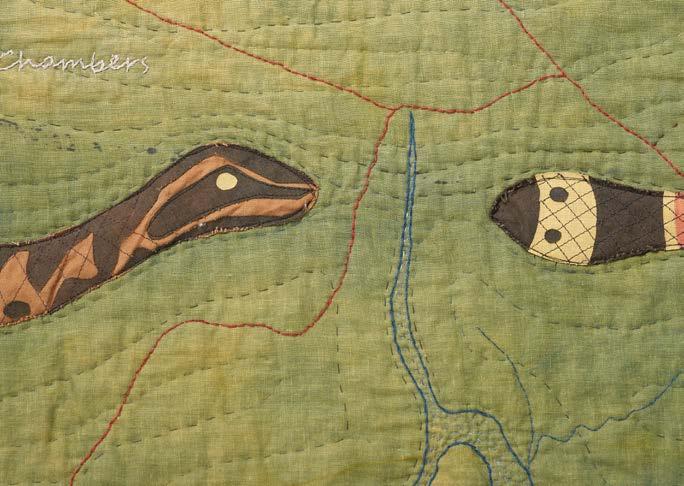

Walter White’s NAACP undertook its own investigation, led by Assistant Field Secretary LeRoy Carter, who discovered that out on the Jesup Highway, the

guards had “ordered the Negro prisoners into a ditch occupied by poisonous snakes.” The prisoners “had simply refused to go into the rattle-snake infested swamp waters without boots.” Those who resisted the order were, the NAACP believed, singled out and shot. In a letter to Governor Thompson of Georgia dated July 14, White wrote: “Human beings, even though they be convicts, and even though they be Negroes, are entitled to full and complete protection from murderous state officials.”

NAACP pressure led to a new hearing on the massacre in August. This time, officials were much more skeptical of Worthy’s narrative. Sam Levine, Glynn County Commissioner, testified before the State Board of Corrections that

There was no justification for the killings. The chief of county police and two policemen were there, but they didn’t see any reason to shoot the prisoners. They had tear gas guns they could have used. I saw the Negroes where they fell. Two were killed where they crawled under the bunkhouse and two

others as they ran under their cells. The only thing they were trying to escape was death. Only one tried to get over the fence.35

Levine also believed that there was little evidence of an escape attempt. If the incarcerated men really wanted to escape, he pointed out, they could easily have done so out on the highway, where they were supervised by only two guards, “instead of waiting until they were back in the barracks surrounded by guards and police all heavily armed.”

The State Board of Corrections concluded that the Grand Jury conducted a “one-sided whitewash investigation”36 of the Anguilla Prison Camp massacre. The Board demanded a new inquiry, abolished the camp, and ordered the

seventy prisoners still incarcerated at Anguilla to be transferred to other camps or to the state prison.

Meanwhile, the NAACP and other organizations continued to cover the events and mount protests. Because of this pressure, federal authorities indicted the warden and four guards at Anguilla for violating civil rights statutes in October 1947. The authorities accused them of depriving the eight murdered men of their constitutional rights, specifically the rights “to be secure in their person…and not to be subjected to punishment without due process of law.”

The federal trial began on October 27, 1947. The warden and the guards elaborated on their story, blaming the prisoners for the violence.

Vance Mitchell, the defense attorney, argued that “the men in the detail were rapists, murderers and burglars and all but one had escaped on previous occasions.” He added: “The guards fired upon the convicts in defense of their own lives.” Defense counsel also claimed that the shooting had been necessary to crush a “Communist-inspired plot” to take over the prison camp.

The guards themselves provided conflicting testimony, but they eventually settled on a basic story that, as one guard said, the men “just didn’t want to work.” The guards insisted the warden had “begged” the men to return to work for “1-2 hours or more.”

The guards accused Willie Bell of being a ringleader who refused to labor and then lunged at Warden Worthy, who was forced to shoot him in the leg. At that point, the guards said, prisoners ran and grabbed weapons. In order to prevent the escape and to protect the warden, the guards said they had to open fire. One guard, Renner Bazemore, claimed that in the ambulance Bell told him, “the boys was all in the wrong, it was our own fault.”

The guards claimed the prisoners were dangerous, violent, and confused, and that they courted and deserved punishment and death. The incarcerated men, however, testified that prisoners without boots were told to work in ditches with water and snakes. Those who refused to work were returned to the camp, where they were shot by the warden and guards.

Willie Bell said that the warden did not plead with men to work; on the contrary, he said, the Warden threatened to kill prisoners who weren’t obedient. Bell also denied telling a guard that the prisoners were at fault.

The guards’ testimony was contradictory, and some of it made little sense—there was no rational explanation of how prisoners got supposedly deadly weapons, for example. But the all-white jury was bent on exonerating the defendants, anyway. It deliberated for only thirteen minutes37 before finding the warden and all four guards not guilty.

The massacre at Anguilla has been haunting me for many years. About 15 years ago, I undertook a rigorous independent study focused on histories of the lynching of Black people in the United States. In the course of my reading and research, I stumbled upon a reference to the Anguilla Prison Camp massacre. I was curious and have spent a dozen years since gathering clues and information. I’ve been slowly piecing them together and trying to understand what happened.

Anguilla was a massacre and a lynching. It was a violent response to a labor action. It was egregious. But it was also quotidian anti-Black violence. It was routine. The public paid attention to what happened there, and there was organizing and activism in response. But the killers were repeatedly exonerated by white juries, so it is also an example of white supremacist impunity. Almost no one remembers the incident in 2024.

The convict camp (a euphemism for a prison) closed after the massacre. The current owner of the land recently discovered what happened, despite all of the silences that surround this history. I’m not sure why Anguilla haunts me, but it does. It’s why I keep returning to the scene of the crime(s).

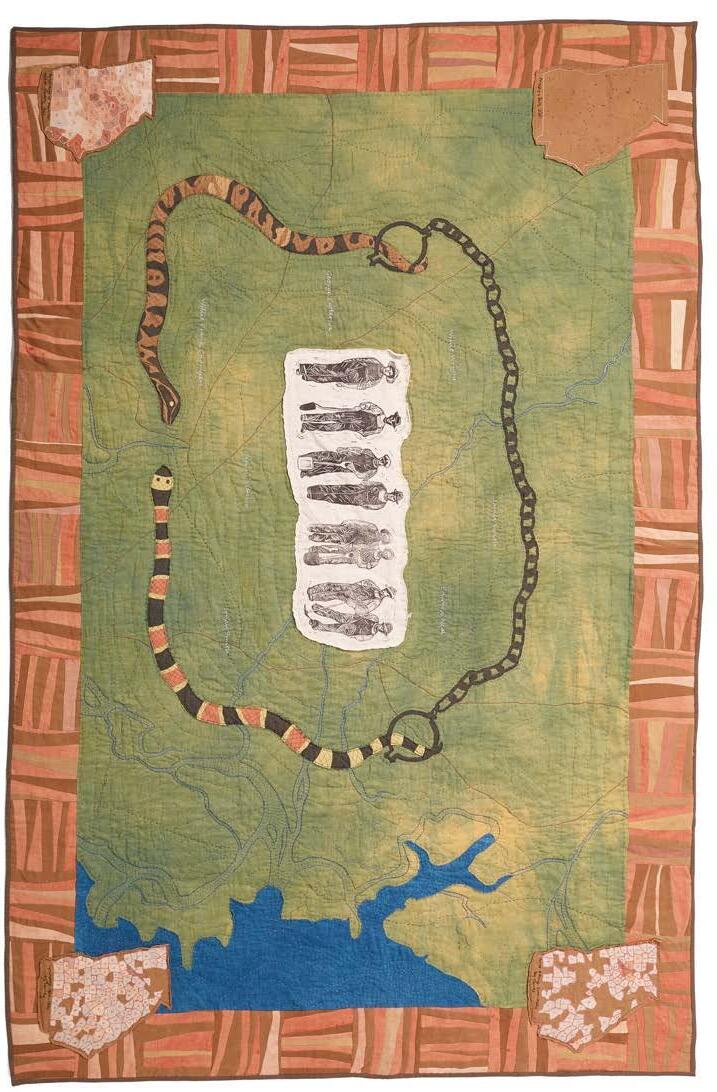

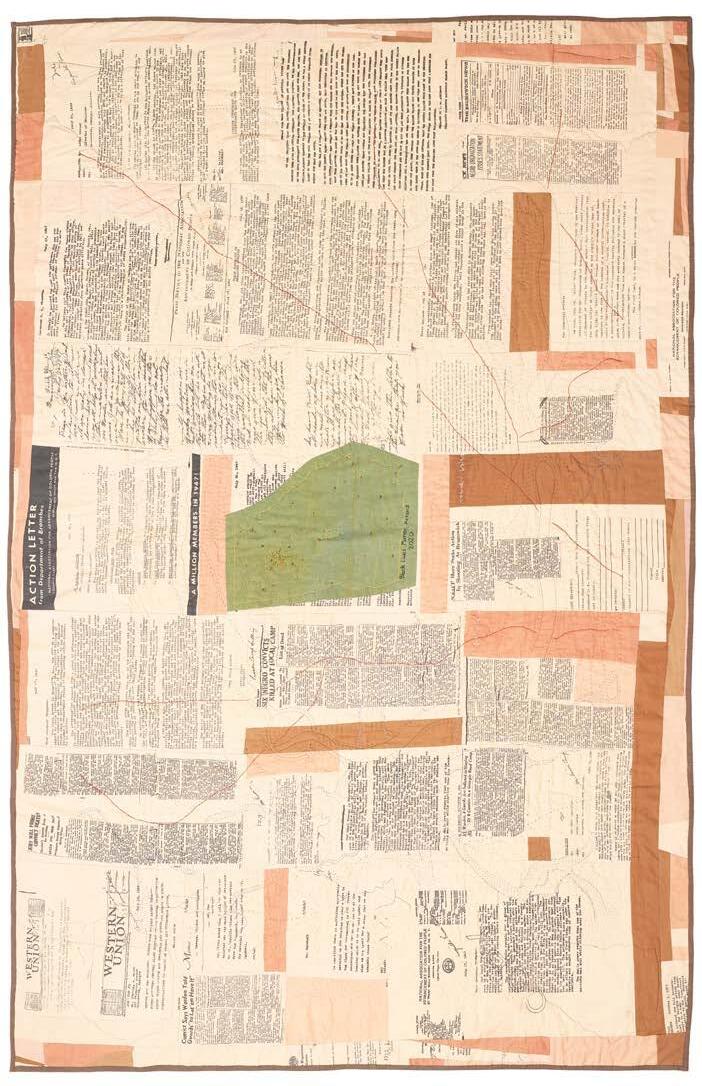

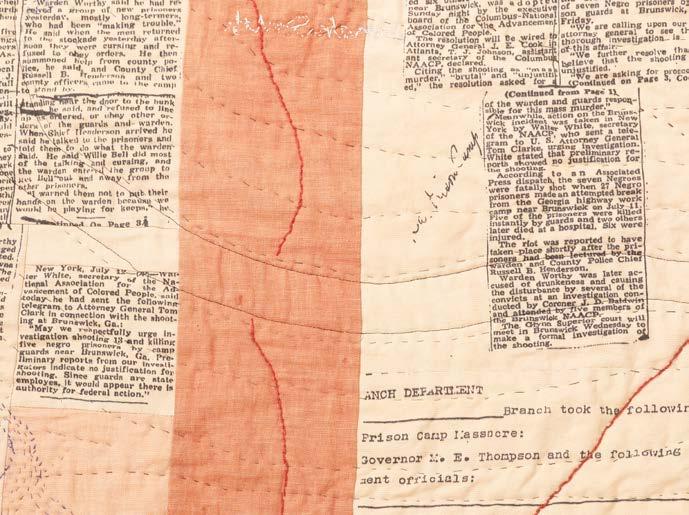

In 2020, I invited my friend Rachel Wallis to collaborate with me to create art about Anguilla. As the first artist in residence at Project NIA, Rachel, who is a self-taught fiber artist, delved into researching the massacre alongside me. The result of our collaboration is the Anguilla Prison Massacre quilt.

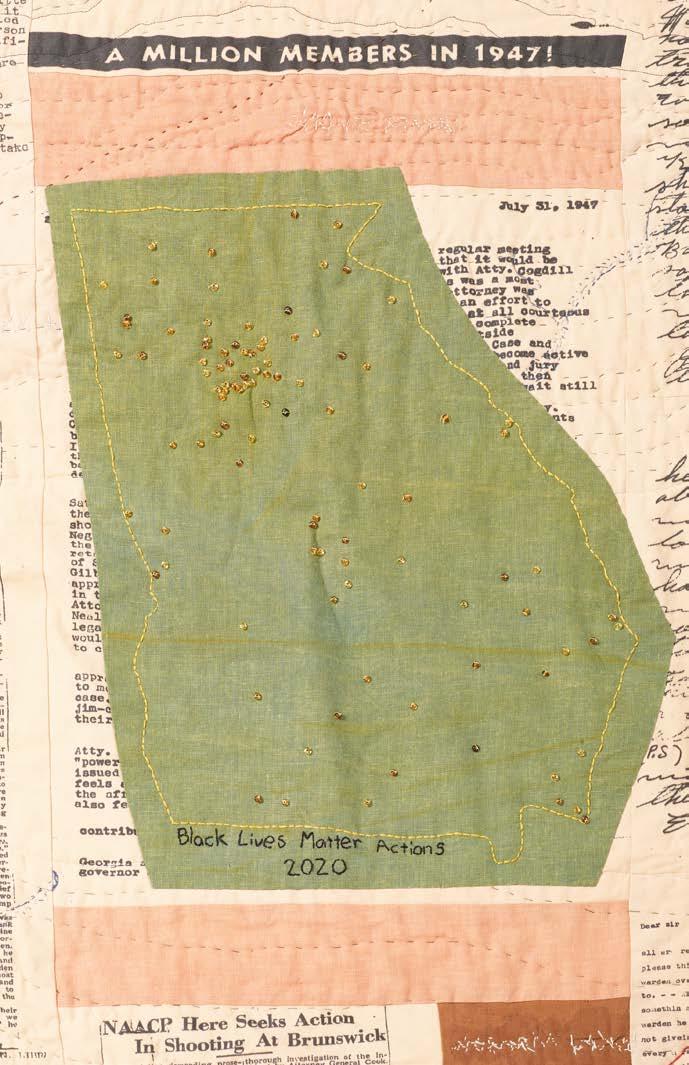

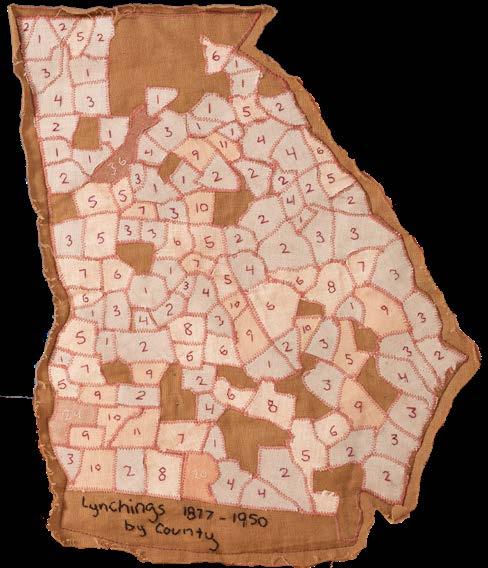

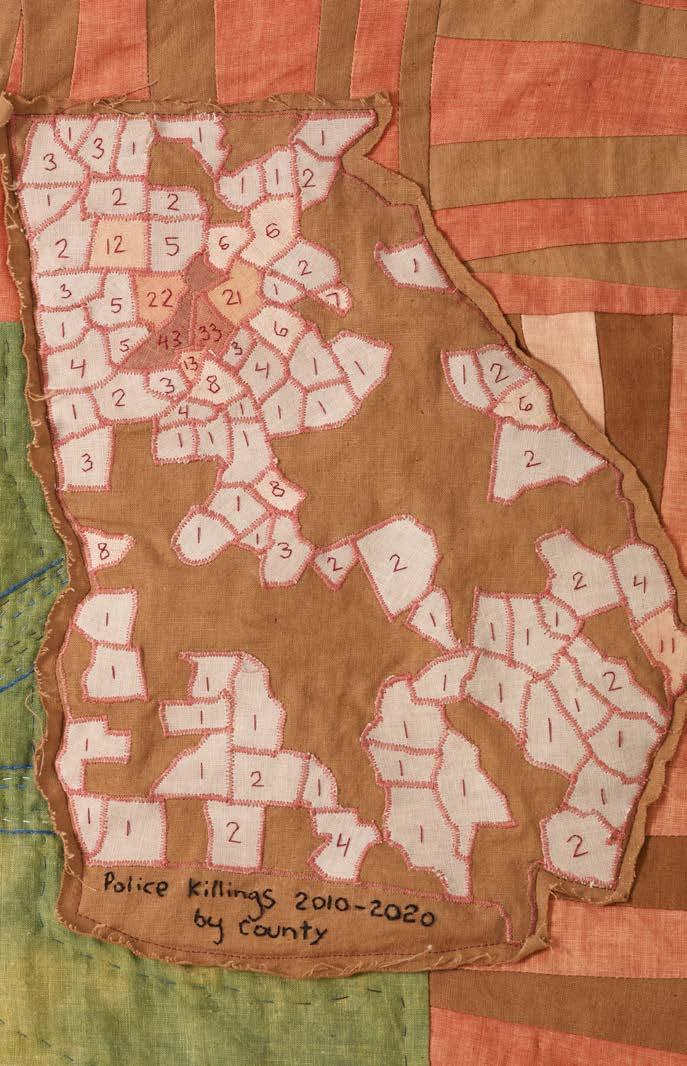

The quilt shows the murdered men surrounded by a border of chains and snakes, and includes their names:

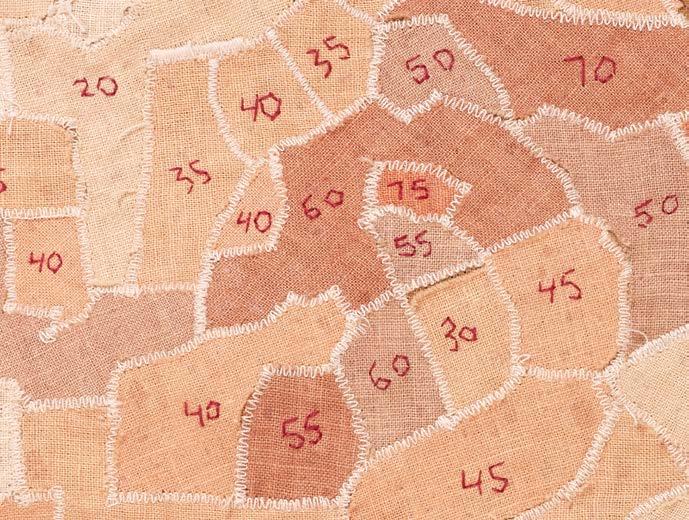

Henry Manson (37), George Patterson (29), Edward Neal (25), James Smith (30), Dan W. Stephens (19), Willie Frank Chambers (36), Willie Amos Wright (26), and Jonah Smith (27). The quilt also includes historical maps that visualize Georgia’s enslaved population on the eve of the Civil War, record lynchings by county, identify the locations of the state’s jails and prisons, and docment Black Lives Matter actions across Georgia in 2020. On the back there are archival documents relevant to the incident, including newspaper articles, telegrams and reports.

Rachel spent over a year working with me to find a creative way to narrate what happened at Anguilla, while also placing the incident in a larger contemporary context. We co-created a quilt based on the research we had done as of fall 2020. In a Facebook post

in March 2021, Rachel wrote about the art project:

“When Mariame [sic] invited me to make a quilt telling the story of the Anguilla prison massacre, I initially felt stumped about how to do it. We know so little about the men who were gunned down for refusing to work barefoot on a chain gang in snake infested waters. There are no photos of them (this is a photo of one of thousands of other chain gangs building roads across Georgia at the time) and all I could find in the state records were their names scrawled in a prison log book, with an entry recording the lie that they died trying to escape. Eventually I made my way back

to maps, as I often do. Maps can tell us so much about our history. They can document a highway system made by the prison laborers rounded up to take the place of [enslaved people]. They can tell the story of racist violence, whether it’s lynchings in the early 20th century or police killings in the 21st. And they can tell the story of resistance. Of the men and women from the NAACP who fought for justice for the Anguilla prisoners, or the Black Lives Matter protesters fighting for justice today.”

The Anguilla quilt is a work of art and it is a map. We know, however, that a map “is not the territory.” Symbols are meaningful and so we dedicate the

quilt to the memory of the murdered men. However, the symbolic must be made real. We are still living with the echo of Anguilla today. The Black men who were mowed down like wheat guide us from the grave; currently incarcerated Black people are doing the same from behind the walls. After the massacre at Anguilla, they shuttered the prison camp and moved the remaining prisoners to other prisons. They should have all been freed instead. It is our responsibility to #FreeThemAll in our time.

Remembering the racist violence done to prisoners in the past is necessary in combating the racist violence to which Georgia and states throughout the country subject prisoners now. The Anguilla Massacre is a chilling example of the place of law enforcement in the racist violence of Jim Crow. In the 1946 Georgia governor’s election and the Moore’s Ford Bridge Lynching, police and the authorities were mostly enablers, refusing to prosecute or stop racist disenfranchisement and racist violence. In Anguilla, by contrast, wardens and guards were the perpetrators and aggressors, using their power and authority to force workers to labor under dangerous conditions, and then shooting and killing them when they dared to object.

In this regard, Anguilla is continuous with ongoing police and prison abuses, such as the death of Sandra Bland in a Texas jail after she was arrested for a minor traffic violation38 or the murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin.39 These events, too, were egregious and quotidian, routine and extraordinary. They

received attention and engendered organizing and activism, but they also reveal the extent of white impunity: police still kill about 100 people every month in the United States.40

We are living in the afterlife of Anguilla. What liberatory future will we build in its wake? Who will we remember?

1 “GEORGIA: I’ll Come Out Dead.” Time, July 21, 1947.

2 L1979-37_205, Stetson Kennedy Papers, L1979-37, Southern Labor Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

3 Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, “Georgia’s Unique And Bloody History With Voter Disenfranchisement,” Talking Points Memo, April 6, 2021.

4 Patrick Novotny. This Georgia Rising: Education, Civil Rights, and the Politics of Change in Georgia in the 1940s (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007), 172.

5 Novotny, 153-4.

6 Novotny, 154.

7 Harold Paulk Henderson,“Eugene Talmadge,” New Georgia Encyclopedia. September 9, 2019.

8 Novotny, 173-174.

9 Novotny, 175.

10 Novotny, 175-6.

11 Novotny, 177.

12 Joseph L. Bernd, “White Supremacy and the Disfranchisement of Blacks in Georgia, 1946.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 4 (1982): 502.

13 Bernd, 175.

14 Bernd, 178.

15 Bernd, 190-1.

16 Novotny, 198-9

17 Lulu Snipes, Snipes’ mother testified to there being 4 men who drove by and called Snipes away from the dinner

table and shot him outside. Williamson testified that Snipes owed him $10 and an argument ensued and shot Snipes as an act of self-defense. Novotny, 200.

18 The fight Malcom had with the farmer may have been prompted by the farmer sexually assaulting his pregnant wife. See Matt Stevens, “Secrets of 1946 Mass Lynching Could Be Revealed After Court Ruling,” New York Times, Feb. 12, 2019.

19 “White Mob Lynches Two Black Couples in Walton County, Georgia.” A History of Racial Injustice. Accessed January 10, 2024.

20 Novotny, 210.

21 That October at the Democratic convention, Talmadge’s son, Herman Talmadge read a speech stating that the Black community had not demonstrated their ability to vote intelligently and as a believer of his forefathers’ democracy, the white primary should be restored. Novotny, 201, 210.

22 Ibid.

23 “White Mob Lynches Two Black Couples in Walton County, Georgia”

24 Quoted in Laura Wexler, Fire in a Canebrake (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013): 78.

25 Greg Bluestein, Ex-governor investigated in 1946 lynchings, NBCNews.com, June 15, 2007.

26 Novotny,191 .

27 Ibid, 324; Bombing Is Linked to News Crusade.

28 From Death Certificates of Murdered Men.

29 “Convict Leasing.” Equal Justice Initiative. November 1, 2013. 30 “Slavery By Another Name: Chain Gangs.” PBS. Accessed January 10, 2024.

31 “GEORGIA: I’ll Come Out Dead.”

32 Charlie Veal, sworn testimony, Coroners’ jury testimony, July 11, 1947 (NAACP file copy).

33 “Convict Says Warden Told Guards ‘to Let ‘m Have It,” Associated Press, July 12, 1947

34 “Picture of the Week,” Life, 7/21/47; Press Service of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, “Flaws Revealed in Massacre Reports,” July 18, 1947, NAACP file

35 “State-Operated Convict Camps For Road Work Ended by Georgia.” New York Times, August 12, 1947.

36 “Georgia Sets Inquiry in Road Camp Killings.” New York Times, August 13, 1947.

37 “Mass Killing Group Freed.” Arizona Republic, November 4, 1947.

38 “Sandra Bland dies in jail after traffic stop confrontation.” History.com. Accessed January 10, 2024.

39 Steve Karnowski. “Chauvin murder conviction upheld in George Floyd killing.” APNews. April 17, 2023.

40 Sam Levin. “2023 saw record killings by US police. Who is most affected?” Guardian, January 8, 2024.

This has been a multi-year project and many people contributed to it. My sincere thanks to Pamela Quintana, Claire Schwartz, Noah Berlatsky, Carolyn Chernoff, Jacqui Shine, Rachael Zafer and many others. Thanks to Lulu Johnson and Devika Sen of Partner & Partners for designing this publication. Rachel Wallis took a leap of faith when I asked her about co-creating a quilt based on this tragic incident. I am truly so grateful for our collaboration and for what came of it. Finally, I hope that the men murdered at Anguilla are resting in peace. I uplift your names and honor your lives.