The Future isn’t Human - And it isn’t Merciful.

The Future isn’t Human - And it isn’t Merciful.

There are moments when technology advances faster than the institutions meant to govern it. When familiar frameworks no longer apply, and power shifts quietly — not with ceremony, but with consequence.

This issue of Inner Sanctum Vector N360™ was built for such a moment.

Artificial intelligence is no longer experimental. It is operational — embedded in command systems, shaping battlefields, accelerating decision cycles, and redefining sovereignty, control, and accountability. The challenge before us is not whether AI will be used, but whether it will be understood, governed, and restrained.

Across these pages, a clear truth emerges: technology does not remove the burden of judgment — it magnifies the cost of getting it wrong. Speed is not strategy. Automation is not authority. Innovation without doctrine does not produce advantage.

AI and the Damned is a deliberate title. The “damned” are not those without technology, but those who deploy it without understanding its limits, dependencies, or consequences. Societies that fail to adapt responsibly — strategically, ethically, and institutionally — will not simply fall behind; they will be overtaken and rendered reactive.

This edition was not created for the news cycle. It was built to last. Long after headlines fade, the questions raised here will remain: who commands when machines decide faster than humans; what victory means when territory, data, and cognition are contested together; and how intelligence can serve judgment rather than replace it.

Inner Sanctum Vector N360™ exists to ask these questions before they become regrets.

This issue is offered not as commentary, but as record. Not as prediction, but as preparation.

Not for the moment — but for those who will look back and say: we saw it coming.

— Linda Restrepo Editor-in-Chief

Inner Sanctum Vector N360™

EUROPE’S INDEPENDENCE MOMENT

Ursula von der Leyen

President of the European Commission

DRONES OF WAR

LTC Amos C. Fox, USA Ret., Ph.D.

WARGAMING WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

COLONEL [Ret] Doug DeMaio

ROYAL OFFICE OF THE UAE N360™ WORLD EXCLUSIVE Amb. Dr. Dunston, P

N360™ MIL-0PS

AI COMMAND-INTEGRATION

DOCTRINE

Dr. Linda Restrepo

150

94

208

GLOBAL THREATS TO UNDERSEA COMMUNICATION CABLES

Dr. Randall K. Nichols

Dr. M. Beckman

UAS/UUV THREATS LAUNCHED FROM SHIPS

Dr. Hans C. Mumm

Dr. Reza Ghaffari DETERMINING POLITICAL OBJECTIVES

Dr. Milan Vego

187

232

CYBER WEAPONS AND CBRNE

Professor Randall K. Nichols

Ursula von der Leyen

A fight for a continent that is whole and at peace. For a free and independent Europe.

A fight for our values and our democracies. A fight for our liberty and our ability to determine our destiny for ourselves. Make no mistake – this is a fight for our future.

I thought long and hard about whether to start this State of the Union address with such a stark appraisal. After all, we Europeans are not used to – or comfortable with – talking in such terms. Because our Union is fundamentally a peace project. But the truth is that the world of today is unforgiving. And we cannot varnish over the difficulties that Europeans feel every day.

Forits place in a world in which many major powers are either ambivalent or openly hostile to Europe.

A world of imperial ambitions and imperial wars. A world in which dependencies are ruthlessly weaponized. And it is for all of these reasons that a new Europe must emerge.

This must be Europe's Independence Moment. I believe this is our Union's mission.

They can feel the ground shift beneath them. They can feel things getting harder just as they are working harder. They can feel the impact of the global crisis. Of the higher cost of living. They feel the speed of change affecting their lives and careers.

And they worry about the endless spiral of events they see on the news – from the devastating scenes in Gaza to the relentless Russian barrage on Ukraine. We simply cannot wait for this storm to pass.

This summer showed us that there is simply no room or time for nostalgia. Battle lines for a new world order based on power are being drawn right now. So, yes, Europe must fight.

To be able to take care of our own defense and security. To take control over the technologies and energies that will fuel our economies. To decide what kind of society and democracy we want to live in. To be open to the world and choose partnerships with allies - old and new. Ultimately, it is about having the freedom and the power to determine our own destiny.

And we know we can do it. Because together we have shown what is possible when we have the same ambition, unity and urgency. I have lost count of the number of times that I was told that Europe could not do this or that.

During the pandemic. On the recovery plan. On defense. On supporting Ukraine. On energy security. The list goes on. Every time – Europe stood united and made it. And we need to do the same now. So, the central question for us today is a simple one. Does Europe have the stomach for this fight? Do we have the unity and the sense of urgency? The political will and the political skill to compromise?

Ordo we want to just fight between ourselves? To be paralysed by our divisions.

This is what all of us have to answer – every Member State, every Member of this House, every Commissioner.

All of us. In my eyes the choice is clear. So my pitch today is a pitch for unity. Unity between Member States. Unity between EU institutions.

Unity between the pro-European democratic forces in this House. I am here – and the entire College is here - ready to make this happen with you. Ready to strengthen the proEuropean democratic majority. Because it is the only one that can deliver for Europeans. This must be Europe’s Independence Moment.

Freedom and independence are what the people of Ukraine are fighting for today. People like Sasha and his grandmother. Sasha was only 11 years old when the Russians attacked. He and his mother sought refuge in a basement in their town of Mariupol. One morning,

they went out to get some food. That's when all hell broke loose. A rain of Russian bombs, on a civilian neighborhood. All became dark and Sasha felt his face burning. He had shrapnel just below his eyes.

In a matter of days, Russian soldiers stormed the city. They took Sasha and his mum to what the Russians called a “filtration camp”. Then Sasha was taken away. They told him he didn't need his mum. He would go to Russia, and have a Russian mother. A Russian passport. A Russian name. They sent him to occupied Donetsk. But Sasha didn't give up. On a stop on the way, he asked to borrow a stranger's phone. And he called his grandma, Liudmyla, who was living in free Ukraine. “Baba, just take me home.” She didn't hesitate a second. Her friends told her she was crazy to go. But Liudmyla moved mountains to get to him. With the help of the Ukrainian government, she travelled to Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Russia, and finally into occupied Ukraine. She got Sasha back.

And through the same long journey, brought him to safety. But their hearts are still broken. Every single day they keep fighting to find Sasha's mum – stuck somewhere by Russia's brutal war. I would like to thank Sasha and Liudmyla for allowing me to share their story.

Sadly, Sasha's story is far from unique. There are tens of thousands more Ukrainian children whose fate is unknown. Trapped. Threatened. Forced to deny their identities. We must do everything in our power to support Ukraine's children. This is why I can announce that, together with Ukraine and other partners, I will host a Summit of the International Coalition for the Return of Ukrainian Children. Every abducted child must be returned.

This war needs to end with a just and lasting peace for Ukraine. Because Ukraine's freedom is Europe's freedom. The images in Alaska were not easy to digest. But just a few days later, Europe's Leaders came to Washington to support President Zelenskyy and secure commitments. Real progress has been made since then. Just last week 26 countries in the Coalition of the Willing said they were ready to be part of a reassurance force in Ukraine or participate financially – in the context of a ceasefire.

We will continue to support all diplomatic efforts to end this war. But we have all seen what Russia means by “diplomacy”. Putin refuses to meet President Zelenskyy. Last week, Russia launched the largest number of drones and ballistic missiles in a single attack. Yesterday, 13

there was a missile attack on a village in Donetsk, targeting people waiting to pick-up their pensions.

More than 20 were killed.

And just today we have seen a reckless and unprecedented violation of Poland's and Europe's air space by more than 10 Russian drones. Europe stands in full solidarity with Poland. Putin's message is clear. And our response must be clear too.

We need more pressure on Russia to come to the negotiating table. We need more sanctions. We are now working on the 19th package in coordination with partners. We are particularly looking at phasing out Russian fossil fuels faster, the shadow fleet and third countries. And at the same time we need more support for Ukraine.

Noone has contributed as much as Europe. Close to €170 billion of military and financial aid so far. More will be needed. And it should not only be European taxpayers who bear the brunt of this. This is Russia's war. And it is Russia that should pay.

This is why we need to work urgently on a new solution to finance Ukraine's war effort on the basis of the immobilized Russian assets. With the cash balances associated to these Russian assets, we can provide Ukraine with a Reparations Loan. The assets themselves will not be touched. And the risk will have to be carried collectively. Ukraine will only pay back the loan once Russia pays for the reparations. The money will help Ukraine already today.

But it will also be crucial in the mid- and long-term for Ukraine's security. For example, funding for strong Ukrainian armed forces as the first line of security guarantees. We will propose a new program. We call it Qualitative Military Edge. It will support investment in the capabilities of the Ukrainian armed forces. Take drones for example. Before the war, Ukraine had none. Today, it is Ukraine's use of drones that is accounting for over two thirds of Russian equipment losses. That is not just an edge on the battlefield.

It is a reminder of the power of human ingenuity in our open societies. But Russia is catching up fast, supported by Iranian designed Shahed drones. And it is seizing the advantage of industrial mass production. Saturday, in one single night, Russia sent 800 drones to Ukraine. So ingenuity helped to open a door for Ukraine's defense. But raw industrial might, on the other side may threaten to sweep it closed. So we can use our industrial strength to support Ukraine to counter this drone warfare. We can help transform Ukrainian ingenuity into battlefield advantage – and into joint industrialization. This is why I can also announce that Europe will front load €6 billion from the ERA loan and enter into a Drone Alliance with Ukraine.

Ukraine has the ingenuity. What it needs now is scale.

And together, we can provide it: so that Ukraine keeps its edge, and Europe strengthens its own.

Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission

� Editorial Comment (N360™) Ursula von der Leyen’s State of the Union makes clear that Europe’s survival depends not only on unity, but on independence in defense, technology, and economics. For Inner Sanctum Vector N360™, the lesson is direct: the next frontier of sovereignty is digital and industrial power. Europe’s fight is not just against external threats — it is for the ability to command its own future in AI, cyber, and innovation.Inner Sanctum Vector N360™ extends our sincere thanks to President Dr. Ursula von der Leyen and her staff at the European Commission for making this presentation possible.

Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission

Ursula von der Leyen has served as President of the European Commission since 2019, the first woman ever to hold the post. In this role, she has led Europe through defining crises — from the pandemic to Russia’s war in Ukraine — while advancing a bold agenda for security, digital sovereignty, and climate transformation.

Previously, she was Germany’s Minister of Defense, where she pushed NATO modernization and re-anchored Germany’s role in transatlantic security. She also held senior ministerial posts in labor, social affairs, and family policy, building her reputation as a decisive and pragmatic leader.

Today, von der Leyen is at the center of Europe’s global posture, pressing for unity, resilience, and innovation as the cornerstones of the continent’s future.

By LTC Amos C. Fox, USA Ret., Ph.D.

Introduction

Are drones changing the ways in which wars are fought? And if so, how does that change contribute to, or take away from, how combatants win and lose wars? Those two questions are the central ideas that this article seeks to answer. These questions are challenging to consider because it is often difficult to separate the reporting from the excitement and institutional bias that is enmeshed throughout the open-source information on the subject. Likewise, it is equally challenging to separate general statements about drones, such as that they are gamechangers or that they are fueling a new

revolution in military affairs, from their contextual relevance. In the case of this article, that contextual relevance is identifying the drone and drone warfare’s contribution to land wars. Why land wars? Because, as scholar Christopher Tuck writes:

The fundamentals of land warfare often vary from those of other environments because of the effects of land itself. Land… exerts a powerful influence over the method required to fight over it. Success in land warfare matters: because humans live on land, occupying it or defending it

successfully can have decisive political effects.

Tuck also notes that the techniques and causalities in land wars differ greatly than those in other domains, to include the air, space, and maritime domains. Therefore, attempting to understand the impact of a technology like drones and how it is employed, like drone warfare, in a specific domain requires a domain-specific theory of war.

Similarly, theorist Carl von Clausewitz asserts that centers of gravity are the hub of all power from which a combatant’s strength is most concentrated. He qualifies that assertion by stating that centers of gravity often reside in a combatant’s army, their capital, and/or their alliances. Although writing from the position of a theorist enmeshed in 19th century wars and warfare, the validity of Clausewitz’s qualifications remains relevant.

This is because of the important link between land war and the decisionspurring outcomes in war that policymakers require. Thus, combatants must apply maximum attention, and pressure, to the element(s) of Clausewitz’s center of gravity which best advances their policymaker down the path of profitable strategic outcomes and advantageous war termination. Yet, a combatant must simultaneously deny that approach to their adversary.

Itis easy to get lost in the ink that’s been spilled regarding the drone and drone warfare’s revolutionary, or evolutionary, impact on war. It is quite difficult, however, to find practical assessments that are balanced against the drone’s ability to accomplish the requirements needed to generate win conditions that actively contribute to their respective policy aims in war. Nevertheless, this article attempts to breach those barriers. In doing so, this article provides a useful theory to make that assessment and determine the drone and drone warfare’s game-changing utility in land war.

To examine these questions with rigor, this article scrutinizes the question of the efficacy of drones and drone warfare through the lens of land war and ground combat, which scholars like Ben Connable, Christopher Tuck, among many others, remind the reader, are the most common type of war. In doing so, this article posits two main ideas – yes, drones are game-changing. They have created new problems for military leaders to address on the battlefield, which in turn is fueling new technology, strategy, doctrine, and force structure. Drones and drone warfare, however, are not revolutionizing warfare, at least in land wars, in a strategic way.

That is, drones and drone warfare are not generating victory in war on their own, any quicker than we might otherwise expect,

nor at a fundamentally cheaper cost. The primary reason for this is because despite being proficient at eliminating many threats, drones lack the capability to control the ground. The secondary reason for this, which directly supports the concept of control, is that drones and drone warfare are generally incapable of accomplishing the basic requirements that a force must realize to be successful in land wars. These requirements include taking and retaking land, holding territory, clearing hostile threats from challenging terrain, controlling borders and sealing boundaries, and protecting populations.

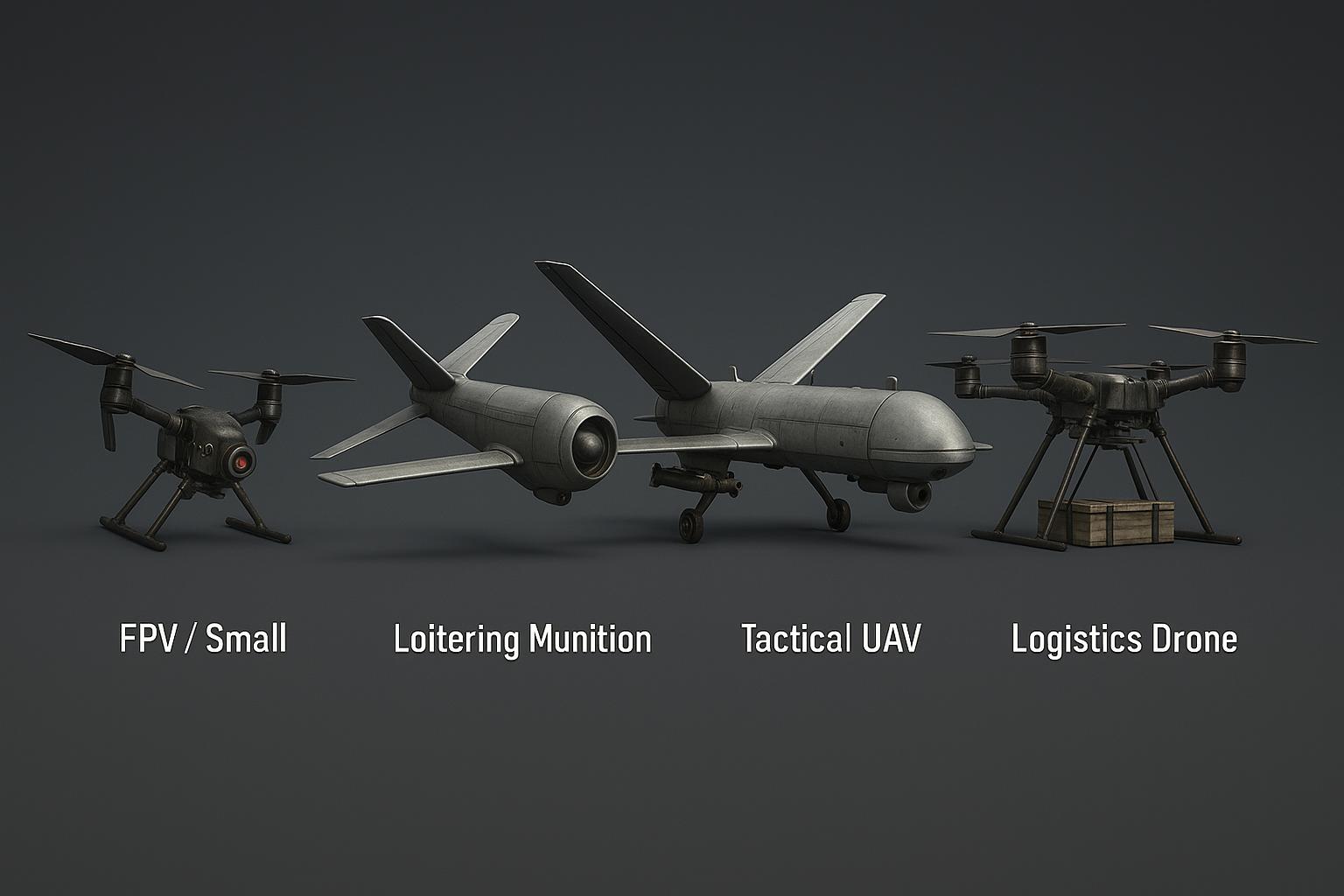

Tosupport this hypothesis, I introduce a theory of land war to link the concepts of control, land wars, and the requirements of land war into a practical logic. Next, I cross-examine drones and drone warfare against the requirements of land war, each of which consists of two supporting conditions, to identify which of those tasks drones can, and cannot, accomplish.

Those findings are then examined comprehensively to demonstrate that while drones have changed how combatants fight wars—especially land wars—drones and drone warfare are unable to control the ground. To be sure, drones and drone warfare have not fundamentally altered the fact that land wars are won through the control of territory. To this point, historian Lawrence

Freedman posits that “Winning a war requires controlling territory, and that will always necessitate supporting ground forces.” Control of territory has always been, and will remain, the most germane causal effect that directly impacts the options available—or unavailable—to policymakers as they relate to either side’s war termination criteria. As a result, warfighting technology and approaches to warfare that de-emphasize or neglect the control of land, like drones and drone warfare, contribute to long, deadly, destructive, and extremely costly wars. Based on those findings, this article concludes with a set of policy recommendations. The recommendations are intended to help influence how policymakers understand the drone’s contribution to war and how policymakers and senior military leaders should approach organizing, equipping, and operating their forces in the future.

State and non-state actors fight land wars for a host of reasons. Charles Tilly, Stathis Kalyvas, Carl Schmitt, and others assert that common themes for these wars include sovereignty, territorial control, the domination (or elimination) of people, societies, markets and political institutions, the liberation of oppressed societies, to wage insurgencies, and to eliminate insurgencies.

Control is the guiding principle behind each of these justifications for war. To be sure, Stephen Biddle comments that control—of land, people, markets, and politics —is the central theme that underwrites why actors engage in land war. Put another way, control is the causal mechanism in land wars. This is because control enables an actor to generate battlefield outcomes which open the political decision space needed to provide policymakers with a range of strategic options for successful war termination. Conversely, a lack of control over territory, people, and competing militaries results in policymakers possessing fewer bargaining chips and thereby negotiate war termination—if they are profitable enough to make it that far—from a position of weakness and dependency.

Drones are tactically effective, but strategically indecisive. They cannot control terrain, win wars, or generate the political outcomes necessary to terminate conflict on favorable terms.

Biddle posits that to gain control in land wars armies must (1) destroy hostile forces, while protecting one’s own combat power, (2) take and hold ground, and (3) maintain the time to destroy hostile forces. Biddle’s points are well-taken but slightly miss the mark because they emphasize the element of gaining control, but do not fully account for the range of actions required to also

maintain control. For that reason, a broader range of requirements is needed.

To gain and maintain control in land wars, land forces—augmented by an everincreasing panoply of joint and multidomain capabilities—must accomplish a set of six basic requirements to achieve control, maximize the impact of military operations, and profitably advance themselves toward war termination. These requirements— discussed in detail below—are not reserved just for conventional wars, but are equally applicable to small wars, insurgencies, and counterinsurgencies. Thus, these requirements span a range of wars upon which armies—both state and non-state— conduct military operations in support of political institutions.

It is also important to highlight that these requirements are not a checklist of actions that armies must complete sequentially, but rather they are determined by situational necessity. Appreciating that control is the causal mechanism at the root of land wars, it is therefore prudent to examine the six requirements and the accompanying conditions of land war.

First, land forces must take control of physical terrain from an enemy force or hostile threat (Requirement 1). These two conditions include defeating an occupying

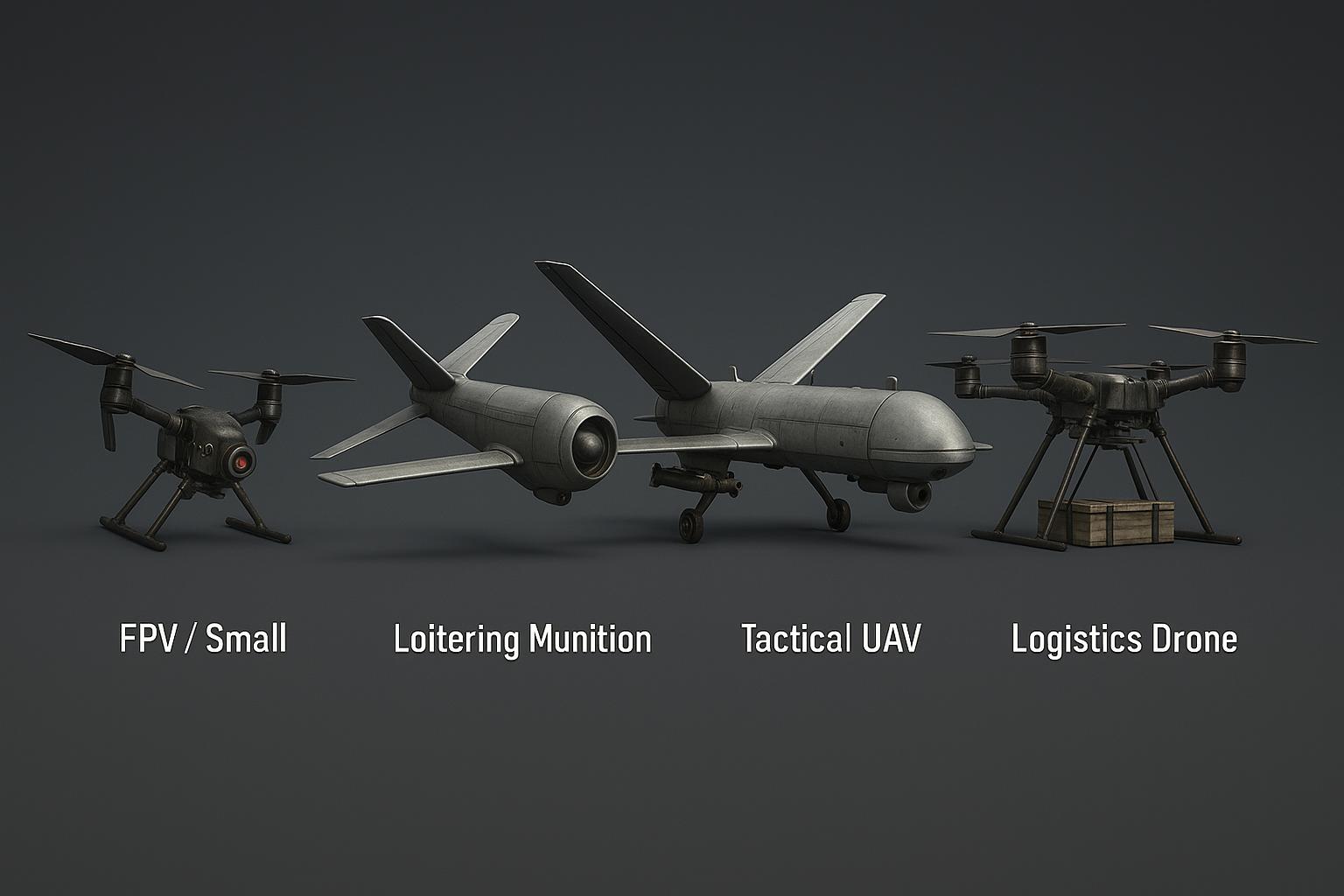

Cheap, expendable, close-range strike and recon

Self-destructs on target; precision anti-armor or antiradar

Longer endurance, ISR + strike, supports battalionlevel ops

Moves supplies and batteries: limited range/payload.

land force (Condition 1a) and controlling the contested terrain (Condition 1b).

Second, land forces must retake control of physical terrain from an enemy force or hostile threat (Requirement 2).

Like Requirement 1, the conditions for Requirement 2 include defeating an occupying land force (Condition 2a) and controlling terrain (Condition 2b).

Third, land forces must clear threat forces from challenging terrain, such as densely forested areas, mountainous terrain, and more importantly, urban areas (Requirement 3). The conditions for this requirement include removing a hostile land force from the contested terrain (Condition 3a) and controlling that terrain (Condition 3b). Fourth, land forces must hold, or retain, physical control of terrain from an enemy force or hostile threat, to include possessing the wherewithal, capability, and capacity to thwart looming counterattacks (Requirement 4). The conditions associated with Requirement 4 include defeating counterattacks (Condition 4a) and controlling the contested terrain (Condition 4b). Fifth, land forces must seal the physical boundaries and/or borders of a designated geographical area of interest (Requirement 5). The conditions associated with this requirement are controlling territory at the nexus of contestation (Condition 5a) and defeating enemy counterattacks seeking to overturn the balance of power at that nexus

(Condition 5b). Sixth, land forces must protect the civilian population of a contested geographical area from harm (Requirement 6), otherwise they risk losing internal control of the land they seek to dominate. The conditions required for this requirement include preventing civilian harm and minimizing collateral damage (Condition 6a) while maintaining control of the contested territory (Condition 6b).

Viewed collectively, this logic forms the theory of land war (see Table 1).

If the theory of land war is correct, then the capability of the drone and the capacity of drone warfare in relation to that theory must be systematically evaluated to understand the true impact of drones and drone warfare on contemporary land wars. What’s more, this feedback will provide forecasts that can also be used to measure the potential impact of drones in the future of 21st century land war. To conduct this assessment, drones and drone warfare must be evaluated on their ability to accomplish both the theory’s six requirements and each requirement’s two

conditions. The findings from that assessment will help illuminate the drone’s true potential and help fuel policy recommendations for further military innovation.

This assessment executes a simple twostep process. The first step is to evaluate whether drones can accomplish the supporting conditions for each of the theory’s requirements. The second step is to balance the outcome of those evaluations against a basic logic. The logic supposes that each of the requirement’s two conditions must be met for the overall requirement to be achieved. If only one, or none of the conditions are met, then the requirement is not achieved (see Table 2).

The final step is to collectively analyze scoring of the requirements and assess how that contributes to the theory’s causal mechanism (i.e., control). If any of the theory’s requirements are not achieved, that implies several things about drones and drone warfare’s importance and position in land wars.

First, if drones are unable to accomplish the requirements of land war, the implication is that drones and drone warfare do not directly gain or maintain control in land wars. Thus, their contributions must be situated

contextually in relationship to how their functions support a land force’s ability to gain and maintain control in land war.

Second, if drones do not accomplish the requirements prescribed in the theory of land war, then the implication is that their contributions are auxiliary to those of a land force. That is, drone and drone warfare’s function supports and/or enables the land force to gain and maintain situationally relevant control in land war.

Third, if drones cannot accomplish the requirements of land war, another implication is that drone and drone warfare’s enabling functionality might be the key catalyst within a larger cohort of combined, joint, and/or multi-domain capabilities, whether this is in an offensive or defensive capacity. The findings from this assessment are used to provide a set of policy recommendations for continued military innovation and strategy development.

Can drones take and retake physical control of territory? Likewise, can drones defeat an occupying army (Condition 1a and 2a) and control contested territory (Condition 1b and 2b)? These two requirements are evaluated simultaneously because they contain matching conditions.

Currently, UAS drones cannot physically control territory. They are unable to land on the ground, defeat an occupying force, and deny control of that land to the vanquished foe through their physical presence on the battlefield. That isn’t to say that it isn’t something UAS might be able to do in the future, but it is not a task that they can currently accomplish. Moreover, that is a potential angle for further development in drone warfare in the future.

Despite their game-changing role on the battlefield, drones do not meet the basic requirements of land war: taking, retaking, holding ground, sealing borders, or protecting populations.

Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) are also drones. UGVs are not as pervasive as UAS, but as reporting from the RussoUkrainian War notes, their involvement in land wars is increasing. The goal of UGVs is to further reduce war’s demands on humans in the future.

Currently, UGVs are used most often in managing supplies and not in direct combat. However, the U.S. Army and the Marine Corps are experimenting with UGVs in roles traditionally reserved for infantry and armor units. Thus, neither UAS nor UGVs are directly involved in taking territory or retaking territory on the battlefield. Likewise, drones and drone warfare are incapable of controlling terrain.

In some cases, drones have been capable of defeating land forces, at least temporarily (Conditions 1a and 2a).

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War (2020) is a case often highlighted to support this idea. Yes, Azeri drones—most notably the TB-2 Bayraktar—deftly eliminated the ill-positioned and poorly equipped Armenian military during that conflict.

Itis important, however, to note a few qualifying points. First, the theater, or area in which the war took place, was incredibly small –roughly 200 kilometers, or 120 miles. That is roughly the distance from New York City to Philadelphia. I’ve referred to this elsewhere as fighting wars in a fishbowl. By that, the potential effect of a technology in a small area is greater than if that same capability is applied in a larger area. Thus, the potential for UAS drones to dominate an ill-equipped, slow-moving land force in rugged, mountainous terrain, is significant. As a result, the outcome of a war in which a high-tech military operates against a poorly outfitted military, in a fishbowl, should rarely come as a surprise.

Likewise, what Azerbaijan’s victory actually shows isn’t the dominance of drones and drone warfare, but that the principles of combined arms persist. Specifically, Jonathan House highlights that for a force to remain credible it must possess capabilities that allow it to apply tools that take advantage of an adversary’s military vulnerabilities, or apply tools that

accentuate its own advantages, and in both cases apply tools in a method that heightens its own asymmetric advantages. In the case of Azerbaijan, they accomplished all three of those requirements, whereas Armenia did not, hence the lopsided victory.

Nonetheless, simply copying Azeri force structure trends and hoping for similar battlefields and associated political decisiveness is a fool’s errand. Unlocking a similar outcome to that of Azerbaijan’s, requires creating a similar degree of combined arms overmatch. Creating that ratio overmatch is situational; that is, it is dependent on the battlefield’s terrain, the threat’s force structure, and the threat’s disposition within that terrain. Therefore, the focus shouldn’t be on the dominance of drones and drone warfare, but instead the emphasis and key insight should be oriented on how drones contribute to a force’s combined arms, joint, and multidomain relational asymmetry on the battlefield. Just mass producing drones isn’t therefore the answer.

Regarding Conditions 1a and 2a, the RussoUkrainian War demonstrates that drones are equally unable to defeat armies. Ukraine’s prolific use of drones has made for great content on social media, but they have done next to nothing to shift the military or political balance in the war to Kyiv’s favor.

To be sure, despite all the hype surrounding Ukrainian drone production, the tactical prowess of FirstPerson View (FPV) drones, and the diversity of reconnaissancestrike capability that Ukraine’s drones provide, Kyiv’s drones have not taken or retaken Ukrainian territory from Russian land forces, nor have they provided a spark of opportunity for Ukrainian land forces to exploit.

On the contrary, Michael Kofman and other analysts highlight that Russia continues to gradually gain ground in Ukraine. What’s more, drone warfare—both Ukrainian and Russian—has frozen the front lines, accelerated attrition, and continues to elongate the conflict in time. Likewise, Russia’s use of drones, which at this point in the conflict is quite similar to that of Ukraine’s, is equally unable to defeat Kyiv’s defensively minded army.

Despite providing tactical and operational game-changing capability, and delivering innovative technology to the battlefield, drones have hastened combat toward attritional and positional warfare. Drones and drone warfare have done so by depriving armies of their inherent tactical and operational mobility. In doing so, drones and drone warfare have driven mobile land forces, and their accompaniment of firepower, out of plain sight and underground.

The ever-present threat of drones has created a psychological condition which some are referring to as drone phobia. This has resulted in the battlefield turning into a static front. Function is important to mention here.

The function of armies is to fight and win battles in order to gain situational control which is pursuant to strategic objectives. The function of drones, on the other hand, is to fight and win microengagements, often just a single drone eliminating one target, with no concern nor ability to gain or maintain control of the ground.

In effect, the drone’s micro-engagement rarely contributes to strategic objectives. Stated another way, these microengagements and their outputs and effects are but mere blips on the strategic radar and do not contribute to creating the strategic pressure required to generate political decisions. At this junction, a brief mention about ‘spectacular’ applications of drone warfare is required.

Spectacular applications of drone warfare, like Ukraine’s Operation Spider Web, emphasize this point. Ukraine’s attack used drones as a show of force, to eliminate the operational and strategic capability and

capacity of Russia to apply stand-off warfare against Ukraine.

Yes, this type of operation potentially illuminates innovative ways that drone warfare can be used in future war, but it also emphasizes a disconnected understanding of how operations support strategy. The operation did not affect the strategic or operational balance of power as it relates to control of Ukraine’s land, which is a key victory condition for both Russia and Ukraine. In addition, arguments for how this operation is a harbinger of future war only point to the operation’s output (i.e., a bunch of burning aircraft on airfields) and not to how the operation fits within the requirements of land war, nor how it impacted, or didn’t impact, the control of territory.

Drones must fulfill two conditions that meet the requirement of clearing hostile forces from contested land.

First, drones must remove a hostile force from difficult terrain (Condition 3a). Second, drones must be capable of controlling contested terrain (Condition 3b). This article has already established that drones cannot control contested

terrain, so the focus moves to removing a threat from contested terrain.

Removal means one of two things. First, removal means eliminating (i.e., killing or destroying) all threats within a specified geographic area. Second, removal means inflicting sufficient losses on a threat to wholly sub-optimize any rational reason to remain such that the threat’s military and/or political leader directs a withdrawal from that geographical area. Scholar Antulio Echevarria asserts that in stand-off warfare (i.e., fighting beyond direct fire contact, and often from the air domain) the defender often seeks refuge in complicated terrain. Echevarria’s findings echo the work of systems theorists Donella Meadows, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, and Lars Skyttner’s research into General Systems Theory and the inner workings of complex, open and dynamic systems. They find that when challenged with survival, an open system—like military forces—adapt their routine operating mechanics and seek alternative means to survive and reestablish order. In the case of military operations, when attacked, a defender will naturally seek cover, concealment, and deceptive operations in order to survive.

“TECHNOLOGY CHANGES THE TOOLS OF WAR, NOT THE NATURE OF IT.”

Likewise, attacks from above are rarely decisive in resolving a tactical or

operational military problem. As a report from the RAND Corporation highlights, attacks from above expand the problems in land wars by forcing the defender to seek additional cover, concealment, and deceptive measures to protect themselves and ensure their survival.

This is nothing new in war. Theorist Alexander Svechin, writing in the early 20th century, for instance, posits that the first rule in war is to protect oneself against what he deems “decisive blows.” History books and other publications are littered with accounts of how massive aerial bombardments, or precision strike campaigns—whether artillery or airpower— did little to dislodge ensconced military forces intent on holding terrain. Verdun, Passchendale, Operation Goodwood, Metz, and the Ho Chi Mihn Trail are classic examples of this phenomenon from military history.

In turn, the military situation required infantry and other land forces to enter that terrain and physically extricate the hostile force. Biddle and Carlo D’Este offers a good example of this phenomenon. They each write that during the aerial prelude to the ground phase during World War II’s Operation Goodwood, German defenders either hid underground or vacated the area under bombardment to protect themselves and ensure their survival. Once the bombardment lessened, the Germans, who suffered little losses in the aerial

attack, reoccupied their defensive positions. As the British land forces subsequently moved forward and attacked, they ran into a stalwart German defense, which ended up mauling the British army, who should have otherwise completely overrun the Germans. As these examples illustrate, aerial attacks, regardless of their precision, play a supporting and enabling role for armies in land war. This is because when a combatant attacks another combatant, the attacked force seeks protection and survival, thus making the attacking force’s follow-up assaults to neutralize, or destroy the threat more difficult.

Setting aside the theory for a moment and looking at a contemporary example is instructive. Drone employment and threat response follows a similar pattern today. Drones play an auxiliary role for the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) in Gaza. Despite a sizable drone advantage over Hamas, the IDF had to enter and remove Hamas’ fighters from Gaza because the IDF’s drones—and other tools of stand-off warfare—were incapable of eliminating Hamas’ fighters who were operating in, and from, urban areas. As a result, the combination of ground combat operations and drone strikes (plus joint air strikes) fueled massive collateral damage and civilian harm throughout Gaza, without actually accelerating the IDF to a short, decisive victory.

Likewise, in Ukraine, though drone strikes have been successful in a few spectacular attacks on infrastructure, most of their effects are little more than tactical pinpricks. As a result, neither Russian nor Ukrainian drone operations have proven successful in removing the others army from their static lines. Instead, those operations have caused complimentary developments in protective measures, such as very small tactical land operations, the expansion of trench, bunker, and post networks, and the focus on operating in, and from, urban terrain. This presents both sides in the war with even less opportunity to strike and destroy the opposing army, which as highlighted previously in this article, is one of Carl von Clausewitz’s three primary components of a strategic center of gravity.

Winning the next land war will not come from the side that perfects drone warfare—it will come from rugged, resilient, and mobile land forces capable of closing with and controlling terrain.

Many commenters have enthusiastically embraced the position that drones and drone warfare have redefined war by contributing revolutionary changes to doctrine, military organizations, tactics, and procurement. All those things are likely true, but despite that revolutionary

change, drones and drone warfare have not nullified the requirement to clear hostile land forces from challenging terrain, and to date, they have proven quite insufficient at the task.

Further commentary raises the question of whether drones have made traditional warfare obsolete. While the questions about the drone’s impact on war will persist for the foreseeable future, the fact remains that drones are currently incapable of removing hostile forces from difficult terrain. Moreover, an equally valid argument can be made that drones and drone warfare have further complicated the task of clearing hostile forces from terrain because of their current dominance of the air-ground littoral. Nevertheless, drones are currently incapable of clearing threats from the recessed and hardened terrain to which they often retreat when attacked.

To hold terrain, a force must be capable of defeating counterattacks (Condition 4a) and controlling the contested terrain (Condition 4b). This article has already established that drones cannot control terrain. Yet, can drones defeat counterattacks? The short answer to this question is yes. However, this position is more theoretical at this point because there are insufficient case studies to fully support the argument.

Theoretically, drones do possess the potential to defeat counterattacks, albeit that comes with three qualifications. To defeat counterattacks, the drones must be scaled to the scope of the drone capabilities and capacity present, sufficiently linked as part of a combined arms team, or be operating at a tempo that exceeds the counterattacking force’s ability to effectively protect itself. Examples of this might exist in ongoing conflicts, but insufficient reports of this have surfaced to make this more than a theoretical confirmation.

Nevertheless, for the sake of fairness, this article posits that drones do possess the capability to defeat counterattacks. Yet, viewed collectively, drones are incapable of holding terrain because though they can theoretically defeat counterattacks, they cannot subsequently control the terrain upon which the counterattack is defeated.

Control of boundaries and borders rests upon a force’s ability to both control the terrain that they possess and defeat counterattacks that seek to dislodge their control of that terrain. In this context, controlling terrain includes insulating the area from small-scale penetrations, infiltrations, and infestations by hostile actors, to include subversive individuals and groups. This might appear simple when looking at the problem from a

standard political map, but the problem is vastly more complicated when accounting for the length of the boundary, border, and the physical geography upon which they rest.

The causal mechanism for this requirement is thus control of terrain (Condition 5a), in coordination with defeating counterattacks (Condition 5b). The critical consideration is, are drones capable of controlling the territory that rests along the nexus of contested land? Having already established that drones cannot control territory (Conditions 1a, 2a, 3a, and 4a), it is safe to argue that they cannot control territory at the points upon which two hostile armies sit astride one another. In the previous section, this article also found that drones are theoretically capable of defeating counterattacks, assuming the appropriate conditions are met for the existing situation. When viewed collectively, however, drones are incapable of sealing boundaries and borders because although they can defeat counterattacks, they cannot control terrain.

The theory of land war’s final requirement is the protection of populations; specifically, those within the contested terrain. This requirement, in particular, is what assists the theory to extend beyond

applicability reserved to conventional land warfare, and what makes the theory apply across the spectrum of conflict – from conventional warfare to irregular warfare, small wars, insurgencies, and counter insurgencies. Protecting the population consists of two conditions – preventing civilian harm and collateral damage (Condition 6a) and controlling contested terrain (Condition 6b). As already discussed in this article, drones cannot control terrain, so we must examine whether drones prevent civilian harm and collateral damage.

Protecting civilian harm and collateral damage is a complicated condition to assess because drones often operate as part of a combatant’s integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) network. Again, the Russo-Ukrainian War is instructive.

According to reporting from early 2025, Ukraine is producing drones on a prodigious scale.

Estimates suggest that Ukraine produces 200,000 drones per month. According to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s goal is to produce 4.5 million drones per year, while also stating that “Ukraine is now the world leader in drone warfare.”

Nevertheless, despite their prodigious drone output and their status as the world leader in drone warfare, Ukraine’s drones have not been able to effectively protect Ukraine’s population from Russian

stand-off warfare, to include long-range missile strikes and long-range suicide drone strikes.

For example, on 29 June 2025, Russia attacked Ukrainian cities with 477 drones and 60 missiles. Reports indicate that Ukrainian protection capabilities eliminated 249 of these aerial threats. On 5 July 2025, Russia attacked multiple Ukrainian cities with 550 drones over the course of seven hours.

Two days later, on July 7, 2025, Russia attacked Ukraine civilian areas with 728 drones and 12 missiles. Moreover, on July 31, 2025, another Russia aerial attack killed 31 Ukrainian civilians and injured 159 more.

As of the time of writing, in July 2025 alone, Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian civilian population centers have killed more than 170 civilians and injured another 850. Meanwhile, Russian land forces continue to gradually and consistently press their attritional strategy to make small territorial gains under the broad protection of their

stand-off strikes. The inability of Ukraine to protect its people and infrastructure from these strikes indicates that though drones are an important part of IAMD, they do not adequately protect populations and civilian infrastructure.

Considering the struggles and strife that the world’s self-proclaimed leader in drone warfare has protecting its population with drones, even as part of a larger integrated defensive system, it is appropriate to infer that other combatants will be in an even worse protective posture than Ukraine. Thus, the deduction that drones cannot adequately prevent civilian harm and collateral damage is appropriate. Taking that consideration in conjunction with the fact that drones cannot control territory, it is equally valid to state that drones cannot protect populations.

The analysis in the preceding sections points to the fact that although drones have changed the doctrine, military organizations, tactics, and procurement models in warfare, they do not meet the requirements needed to fulfill the theory

of land wars. That is, drones cannot take, retake, or hold territory. They cannot clear enemy forces from difficult terrain like urban areas or tunnel and bunker networks. Likewise, drones cannot seal borders and boundaries, nor do they adequately protect populations (See Table 3). Therefore, drones and drone warfare might be game-changing and revolutionary, but those outcomes themselves are not directly transferrable to generating strategically relevant outcomes that positively contribute to a combatant’s war termination criteria.

Another way to think of this idea is that although drones and drone warfare might be revolutionizing how combatants can fight wars, drones are not revolutionizing how combatants end their wars. That is, drones are tactically effective, but strategically indecisive. The long-standing continuities of strategic exhaustion, political and domestic will, and fracturing armies, capturing capitals, and splintering alliances are still the dark path to strategic victory in war. By being strategically indecisive, drones are negatively impacting war in Two key ways. First, drones are making wars

equally, if not more, deadly and destructive as they have ever been. This is relative, of course. It is hard to surpass the death and destruction of the 20th century’s two World Wars. However, Ukraine’s ability to mass produce drones on an astronomical scale has allowed it to stave off strategic defeat, but in doing so they have increased the costs of war on both sides of the conflict. Russia has lost more than an estimated 1 million soldiers and thousands of combat systems and combat support vehicles, while Ukraine has lost several thousand soldiers and civilians.

Second, despite the million-plus casualties, and the ability to reach out and touch every point on the battlefield, drones have proven incapable of delivering battlefield results that positively contribute to war termination criteria. For Kyiv, the absence of land forces is what’s holding their strategy back, despite being the world leader in drone warfare. For Moscow, on the other hand, which possesses a significant advantage in infantry and other land forces, their strategy incrementally advances by holding the land they’ve taken from Ukraine, by defeating Ukrainian counterattacks to retake that territory, and by continuing to fortify the newly minted borders along that contested terrain. From this perspective, land forces, not drones, possess more strategic relevance. Thus, the emphasis on drones, at the expense of mobilizing additional land forces, is hurting – not helping – Ukraine. Whereas for Russia, the combination of drone

warfare in conjunction with a grinding strategy of attrition, is slowly advancing Russia to amenable policy outcomes.

This article’s assessment illustrates that drones are a game-changing capability in war. Yet, drones and drone warfare’s inability to control the land and accomplish the critical requirements and conditions of land wars make them strategically irrelevant. Drones and drone warfare, without accompanying operations focused on taking, retaking, clearing, and holding land, while also sealing boundaries and borders, and protecting populations, are the white noise of war –tactics absent any true connection to strategy.

If properly understood, they provide useful insights into how militaries should prepare for the future of war.

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, often pointed to as the future of war, is an outlier in war, not a guidepost to the future. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza, on the other hand, clearly demonstrate the limitations of drone warfare and the continuities in the theory and logic of land war.

Both the Russo-Ukraine War and the IsraelHamas War demonstrate that drones are great auxiliaries to combined arms, joint, and multi-domain operations. However, Ukraine demonstrates that being the world leader in drone warfare means nothing if you lack the land forces to accomplish the requirements needed to win land wars. As such, drones are not replacements for legacy systems, nor does the retention of useful legacy systems reflect a backwardlooking approach to war and warfare. Rather, the retention of legacy systems and formations like field artillery, engineers, ground reconnaissance, and mechanized and armored platforms and formation recognizes the reality that the logic of land war plays in the long history of war.

As U.S. Army officer Bill Murray, analysts Michael Kofman and Justin Bronk, and others assess, drones cannot replace systems like artillery because ground-based legacy systems provide 24hour, all-weather solutions to tactical and operational problems in ways that drones are just not equipped. Without 24-hour, all-weather options, militaries become increasingly fragile and thus prone to surprise, shock, and being entirely overwhelmed.

It is therefore prudent for policymakers, strategists, and senior military leaders to keep the theory of land war at the fore of their minds when pondering military innovation and transformation initiatives.

Innovation and transformation focused on trendiness, a historical interpretations of wars of the past, and misreading contemporary armed conflict is an error. These leaders must keep the land force—and what the land force must accomplish to generate the strategic outcomes needed to fuel positive political decisions—at the top of their priorities.

To that end, militaries require rugged, redundant, and resilience land forces that can move to an objective (e.g., a hostile force, a piece of terrain or area of ground, or the hinge between two or more partners), iteratively apply the appropriate action to that objective—and do so without culminating—to create the situationally relevant conditions needed to advance the strategic balance to their favor.

In doing so, that land force makes positive steps toward war termination from an advantageous position. Innovating to create this type of combined arms, joint, and multi-domain military is imperative. In considering this, it is important for policymakers to keep in mind that their adversaries are also innovating and transforming their technological capabilities and their militaries. Jumping on the proverbial novel technology bandwagon is probably not the best way to truly innovate for the future of war just as throwing out legacy systems because of bad interpretations of contemporary conflicts and selling off the preponderance of one’s army to stay trendy is just bad policy, poor strategy, and tactical suicide.

Land War Requirement Drone Ability The Ground Truth: Why Drones Can’t Win Wars

Take / Retake Territory

Hold Territory

Seal Borders

Protect Populations

Defeat Counterattacks

No

Requires armor + infantry occupation

No

No

No

Cannot clear or secure ground

Drones bypassed; porous defense

Civilian casualties remain high

Partial Effective only when paired with artillery / tanks

Source: N360™ Strategic Assessment, 2025

policymakers must focus prioritization for innovation and transformation on the airground littoral. The air-ground littoral is now the lynchpin to maintaining operational and tactical mobility for land forces capable of, and intent on accomplishing the requirements and conditions of land war. Innovation and transformation strategies must account for drones and mobile short-range air defense

as a protective shield enabling the striking power of land forces operating in the airground littoral.

Policymakers and senior military leaders advancing innovation and transformation initiatives must not place a premium on stand-off warfare via drones and longrange strike.

Rather, if policymakers and senior military leaders are truly interested in generating strategically relevant battlefield outcomes, they should emphasize combined arms, joint, and multi-domain forces that are capable of protecting, moving, and striking at an adversary’s center of gravity —a threat’s army, ‘capital’, and/or alliances— and controlling terrain.

To conclude, winning the next land war will not come from the side that perfects melding drone and maneuver warfare. Winning the next land war will result from positively advancing five lines of effort.

First, militaries must keep the airspace in the air-ground littoral sufficiently open to enable freedom of movement for one’s land forces.

Second, with freedom of movement realized, militaries must use mobile, rugged, resilient, and redundant land force to advance to the threat’s center of gravity.

Third,having closed on the objective, mobile, rugged, resilient, and redundant land forces must continuously apply firepower against the threat’s center of

gravity sufficient to the point that they have gained control of the terrain upon which the conflict is fought.

Fourth, having gained control of the terrain, militaries must reinforce their success and consolidate their gains by retaining control of the air-ground littoral, defeating counterattacks, protecting the local population, and sealing borders and boundaries.

Fifth, militaries must have the tactical, operational, and strategic depth of economic and military resources, plus political and domestic will, to maintain the tactical and operational pressure until the strategic options slowly dwindle for the opposing side’s senior military leaders and policymakers. Drones will play an important role in this process, and they will help set those conditions, but despite being revolutionary and game-changing technology, they will not provide decisive outcomes on their own.

“ EUROPE IS IN A FIGHT ”

A State of the Union Address by

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission.

Dr. Amos C. Fox

Managing Editor, Small Wars Journal

Retired Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army.

Fox is one of today’s foremost voices on modern warfare and strategy. As Managing Editor of Small Wars Journal, he directs the publication’s mission to deliver sharp, fieldrelevant analysis at the intersection of irregular warfare, emerging technologies, and global conflict.

An authority on land warfare and military innovation, Dr. Fox is the author of Conflict Realism: Understanding the Causal Logic of War and Warfare (2024) and has written more than 90 articles and papers across leading journals and policy forums. His expertise is also widely shared through media: he co-hosts the Revolution in Military Affairs podcast and appears regularly on WarCast and Soldier Pulse.

In addition to his military and editorial career, Dr. Fox serves as Professor of Practice with Arizona State University’s Future Security Initiative and lectures in politics and international relations at the University of Houston. His forthcoming books include Maneuver is Dead: Land Warfare in the 21st Century (Bloomsbury) and Multidomain Operations: The Pursuit of Battlefield Dominance in the 21st Century (Howgate).

*This article was originally published by Small Wars Journal and is republished here with permission.

“ Stand back! Be silent! Be still! That’s it…and look upon this moment.

Rejoice with great gladness! Great gladness! Remember it always, for you are joined by it. You are one, under the stars. Remember it well, then…this night, this great victory…so that in the years ahead, you can say,

“I was there that night with Arthur, the King!” For it is the doom of men that they forget.”

MERLIN, EXCALIBUR (BOORMAN, 1981)

In 1991, the author was a senior at the Air Force Academy and witnessed two of the most historic events of the last century play out in the same year: the fall of the Soviet Union and Operation DESERT STORM. In September of that same year, the author also attended pilot training at Sheppard Air Force Base (AFB), Texas, starting a 32-year career in which he would fly nearly 3,000 hours in the F-16, command a fighter squadron, direct a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Air Operations Center (AOC), command a fighter wing, and spend ten years developing air operations, concepts, doctrine, and national strategy. The author would also participate in dozens of base and RED FLAG exercises, three tours in Operation SOUTHERN WATCH, and two tours in Operation IRAQI FREEDOM.

These events form a comprehensive personal experience, but the author cannot access the data that formed them.

Most of it has been lost.

If, as King Solomon said, there is nothing new under the sun, and we have not captured (or cannot access) history, then we are doomed to repeat it. (The Holy Bible New International Version, 1984)

Our memories form many comprehensive experiences, but humans can only accurately recall a finite amount of detail.

We have developed technology to aid our five senses in real-time. We would greatly benefit from technology that stores, accesses, and rapidly processes information individually and collectively, complementing strengths and compensating for our weaknesses. Artificial Intelligence is that technology, a historic inflection point, sweeping through every human endeavor, including war.

Revolutionary technologies evoke both promise and fear, and AI is no exception. In the author’s experience, the Department of Defense (DoD) is slow to adopt gamechanging technologies because they are unproven in combat, where lives are at stake.

They also threaten the established order, causing militaries to retain obsolete equipment and methods for too long. As late as 1945, nations were still sending men on horses and battleships to certain destruction in the face of machine guns and swarms of aircraft. In the author’s experience, this tendency persists; however, with AI, the author has found leaders most concerned with whether they can be trusted with critical information or participate in life-and-death decisions.

With its ability to access, process, and store data, humans can accelerate learning and prepare for competition through Wargaming with AI.

Humans value Intelligence more than any other characteristic. It is the primary discriminator between species and within humanity. We value Intelligence so highly that we are creating our intelligent beings. While Intelligence is critically important, experience and wisdom put it to use. To be successful, even the most intelligent beings must learn, and even the most experienced beings must apply their knowledge intelligently.

Professional, intelligent beings are arguably the most successful.

Encyclopedia Britannica defines them slightly differently: “HI is the mental quality that consists of the abilities to learn from experience, adapt to new situations, understand and handle abstract concepts, and use knowledge to manipulate one’s environment.” (Britannica, 2024) “AI is the ability of a digital computer or computercontrolled robot to perform tasks characteristic of humans, such as the ability to reason, discover meaning, generalize, or learn from experience.” (Britannica, 2024) Because human beings have a basic understanding of their Intelligence, they have created AI to mimic their own. HI is biologically based and

analog, whereas AI is mechanically based and digital. These differences are profound, and HI and AI may be optimized differently.

Dr. Geoffrey Hinton is widely known as the “Godfather of AI.” Frustrated with his attempt to map the human brain through traditional methods, he modeled HI via digital neural networks, culminating his work with Google from 2013 to 2023. Dr. Hinton created AI through many layers of algorithms, each calculating the probability of the next word in a sequence, adding “weight” to perpetually optimized responses, and refining calculations through continuous interactions with source data and HI. The more layers, he said, the more intelligent the computer became. Open AI’s Generative Pretrained Transformer 4 (GPT-4) uses one trillion connections to optimize the computing depth needed to access, process, and store enormous amounts of data.

Incontrast, Dr. Hinton says the human brain’s one hundred trillion connections are optimized for the breadth of decision-making to survive critical experiences. He also believes AI is far more efficient and will surpass HI. However, with ninety-nine trillion more connections than even the most advanced AI, HI appears formidable, especially with AI’s unmatched processing power. (Hilton, 2024)

Britannica Dictionary defines wisdom as “knowledge that is gained by having many experiences in life; the natural ability to understand things that most other people cannot understand; knowledge of what is proper or reasonable; good sense or judgment.” (Britannica, 2024) One can see HI and AI’s specific characteristics reflected in different portions of this definition; HI engages the breadth of one hundred trillion connections to optimize learning over a limited number of experiences, and AI engages the depth of one trillion connections to optimize information processing. Perhaps true wisdom can come from pairing HI and AI. Fortunately, a model already captures this relationship and is widely known in military circles.

Colonel (Retired) John Boyd was a United States Air Force (USAF) fighter pilot who

developed a famous cognitive model, the OODA Loop: Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action. From a defensive position, Colonel Boyd’s standing bet was that he could defeat any challenger in a dogfight in under forty seconds. He used agility and surprise to outpace his adversaries and never lost a bet. Colonel Boyd developed the OODA Loop using the same principles to outpace an adversary’s decision cycle and win, regardless of enemy strength. His seminal work, “A Discourse on Winning and Losing,” adapted the OODA loop to operational warfare, baselining US Marine Corps (USMC) maneuver doctrine. In a very telling note on service culture, the USAF largely rejected Colonel Boyd’s theories for decades while the USMC enshrined his works and artifacts at the Marine Corps University in Quantico, Virginia. (Hammond, 2001)

Maxwell Air Force Base (AFB) is the home of Air University and the LeMay Center for Doctrine, Education, and Training. While serving as the vice commander of the LeMay Center in 2017, the author received an unusual question directly from the Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF). “Is the OODA Loop still relevant in the digital age?” Having studied Colonel Boyd’s work extensively, the author assembled a small group to answer this question comprised of several who had served on CSAF’s Multi-Domain Command and Control (MDC2) Enterprise Capabilities Collaboration Team (ECCT), which designed the plan to integrate Air, Space, Cyberspace, and Electromagnetic Spectrum operations into USAF strategy. Dr. Grant Hammond, an Air War College (AWC) professor and author of the seminal account of Colonel Boyd’s theories, “The Mind of War,” provided tremendous insight. The author had the honor of submitting the following short essay to CSAF.

Colonel John Boyd’s Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action Loop (Source: John Boyd’s “A Discourse on Winning and Losing” – Air University Press)

“The OODA Loop will endure. Technology enhances, but the principles of war will continue to matter. I have contacted Dr. Hammond with your questions, Lt Col “Sugar” Lyle from the LeMay Center, Lt Col Garretson from Air Command and Staff College, and Brigadier General Saltzman (MDC2 ECCT lead).

Dr. Hammond is the expert on John Boyd, but we all concur that the OODA Loop will transcend the digital age because war is and always will be an extension of politics – a uniquely human endeavor. We also agree that the “understand, manage, and create effects” discussion is an OODA Loop by another name. In addition, grids, sensory networks, connections, sharing, and learning will enhance the OODA loop, not replace it.”

“Blue Horizons (a student think tank) coined a term several years ago called the “OODA Point” to describe the time compression the digital age will have on the OODA Loop. Information moves so fast that unaided humans will not have time to observe, orient, decide, or act. To mitigate this, man-machine-teaming will allow humans to delegate subtasks in the OODA Loop to machines while humans retain authority and decision-making. As proposed in the MDC2 ECCT, we seek decision superiority over the adversary – access to decision-quality information by leveraging technology to transcend current seams and barriers. Financial markets work this way already. Humans retain authority while algorithms conduct data-fighting in cyberspace. Many steps are digitally enhanced for humans, thereby expanding the OODA Point back to the OODA Loop within which humans can operate. Dr. Hammond summarizes: “At the base, in his [Boyd’s] view, was the constant

reminder that war is a human activity begun and ended ultimately for what is seen as moral purpose.”

“Orientation is so important to Boyd’s model that he called it the “Big O.” Orientation is about knowing – knowing yourself, your adversary, your environment, assimilating new information, evaluating, and synthesizing all into a contiguous picture that never stops changing.

Like Basic Fighter Maneuvers (BFM), knowing these things allows one to recognize and predict a fleeting opportunity. Like the digital tools we now see, the jet’s systems update the pilot’s contiguous picture, informing his observations, decisions, and actions.

Knowing also allows an operator to create discontinuities in the adversaries’ contiguous picture – that “deer in the headlight” moment –leading to confusion and inaction on his part.

As a Fighter Pilot masters tactics, a MultiDomain Operator must become a practitioner of operational art and strategy. His cockpit will be a digitally enhanced OODA Loop with advanced tools to build decision superiority.

Dr. Hammond summarizes this for the digital age: “Analysis of ‘big data’ does this – finding anomalies and correlations to explore. Exploit the mismatches. Use mission-type orders. Maneuver your adversary to where he decides he cannot win.” (Hammond, 2017).

While answering CSAF’s question, it occurred to the author that Colonel Boyd had already designed the OODA Loop to account for AI in military operations.

The “Big O” Orientation is the most critical step, requiring both the breadth and depth of knowledge to capture a comprehensive picture of a rapidly evolving environment, gain an advantage, and win. (Hammond, 2001) Marvel’s Iron Man models a potential HI/AI relationship, pairing Tony Stark and JARVIS (Just A Rather Very Intelligent System), who complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses in a trusted, interactive relationship. Tony Stark’s one hundred trillion connections optimize Iron Man’s ability to engage a novel environment. In contrast, Jarvis’ one trillion connections optimize Iron Man’s ability to access and process data quickly. However, all decisions remain under the control of Tony Stark, including autonomous tasks meant to enhance Iron Man’s agility in the heat of battle.

According to Carl Von Clausewitz, war is politics by other means, and the author contends that all decisions in war should be human-centered and AI-assisted. (Clausewitz, 1993) If we endeavor to train as we fight, the author also argues that Wargaming should be conducted in the same manner and used extensively to prepare us for warfighting. An example in US history demonstrates how well this can be done. (Pellegrino, 2024).

Wargaming is one the best tools available to prepare for warfighting, and War Plan Orange is arguably the most successful example of planning, Wargaming, and warfighting in US history.

At the turn of the last century, the US rapidly emerged as a world power. To contend with potential adversaries in both oceans, the US developed color-coded plans, each color corresponding to a single adversary.

War Plan Orange was initiated in 1897 to prepare the US for a potential conflict with Japan. While initially assigned to both the Army and Navy, it evolved primarily into a US Navy (USN) plan. While color-coded plans later evolved into the Rainbow Series to address multiple adversaries, the tenets of War Plan Orange endured over four decades of iteration, evolving with geopolitics, technology, and lessons learned from Wargaming. (Miller, 1991)

War Plan Orange was successful because it was part of a whole-of-nation approach designed to prevail in conflict. The hypothesis was simple: defeat a land power with sea and air power through economic strangulation via a naval blockade and aerial bombardment.

However, the Navy extensively developed and adapted the plan to changing conditions, resulting in three stages: securing the western United States, a decisive naval battle with Japan, and the surrender of Japan.

Once the potential of a two-front war became a reality, the Navy planned for resourcelimited initial stages, Japan’s first-move attack, the retreat of US forces to its stronghold in Hawaii, national support, build-up of the industrial base, and an island-hopping campaign across the Pacific. While they did not predict everything, practitioners accounted for new technology through continuous iterations of the plan. Wargaming was critical to this effort. (Miller, 1991)

Wargaming was instrumental in the defeat of Imperial Japan in World War II. Edward Miller’s “War Plan Orange” is the seminal work on this topic and the result of twenty years of research through access to declassified documents from the USN and national archives.

He states that War Plan Orange was “noted and filed in the Navy’s corporate memory” and “genetically coded in naval officers.” (Miller, 1991) According to retired Lieutenant Commander (LCDR) Pete Pellegrino, a Naval War College (NCW) Wargame designer, this genetic coding resulted from Wargaming at the NWC. From 1919 to 1941, NWC conducted 318 wargames, dedicating ninety percent of the college’s curriculum to preparing, executing, and debriefing wargames, many of them for War Plan Orange.

The Wargaming campaign was so successful during this period that Admiral Chester Nimitz stated the following in his address at the NWC in 1960:

“The war with Japan had been enacted in the game rooms at the War College by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise – absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics towards the end of the war. We had not visualized these.” (Pellegrino, 2024)

The NWC succeeded because it educated peer groups on solving problems in relevant scenarios who would later fight and win the war together. Students gained invaluable experience planning, commanding teams, exploring novel issues, solving problems, and integrating real-world change.

Whilethey did not specifically develop War Plan Orange, War Department officials regularly reviewed wargame results and included significant outcomes in the plan. For example, NWC Wargaming of Japan’s developing long-range aerial scouting and “Long Lance” torpedoes produced unacceptable losses of USN capital ships. As a result, USN plans for rapid thrusts into Japanese-held territory evolved into an island-hopping campaign, and students built a valuable, collective database of shared problem-solving needed to outpace an adversary. (Pellegrino, 2024)

Wargaming is as old as civilization itself. What began in the military was adopted in many other areas, each tending to have its definition and set of methods. Colonel (Retired) Matt Caffrey Jr. served as a Professor of Wargaming and Campaign Planning at Air University’s (AU) Air Command and Staff College (ACSC) and as an Air Force Wargaming Institute (AFWI) senior analyst.

In his book, On Wargaming, he summarizes the history of Wargaming and its definitions over the centuries (Caffrey, 2024) “The author maintains that Wargaming has gone through three generations and is entering a fourth. Further, each of these generations needs its own definition.

A first-generation wargame is an abstract competition in which outcomes are determined primarily by the participants’ decisions. This generation began before the Christian era and continues today in wargames like chess and Go.

A second-generation wargame is a simulation game depicting combat. This generation began in the early 1800s and is represented today in most tactical, operational, and strategic games.

A third-generation wargame is a simulation game of armed conflict depicting all (or most) elements of power. This generation began with the Weimar Republic’s political-military wargames and continues today in political-military games, the more comprehensive strategic games, and some insurgency /counter-insurgency games. The emerging fourth generation can be called “peace games,” as they depict the spectrum of competi-tion between nations or groups in which peace is one plausible path to victory. It is tough to pick a starting date, though some more comprehensive political-military wargames and the commercial software game Civilization fit this generation.” (Caffrey, 2024)

The USAF also has its definition of Wargaming and a set of methods. Located at Maxwell Air Force Base (AFB) and part of the LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education, AFWI is the USAF’s premier Wargaming center. AFWI defines a Wargame as “…a unique interactive research model using purposefully selected game participants to generate data that does not already exist in response to purposefully developed scenarios for analysts to use in developing insights or options in response to a sponsor’s problem.” AFWI uses Wargaming as “…a means of applying and reinforcing doctrine-based

warfighting principles taught in officer and enlisted PME programs and supports sponsor requests from Department of Defense components, combatant commands, and Allies and Partners.”

When done correctly, Wargaming should address complex problems with select participants under specific conditions to generate novel data through human interaction.

However, Wargaming is not ideal for more straightforward issues, with participants lacking relevant experience, under general conditions for which definitive solutions already exist, or for problems not requiring humans to interact or create data for further analysis. (Air Force Wargaming Institute, 2024)

Colonel Caffrey’s and AFWI’s definitions reflect the current state of Wargaming; all four generations are being used to help solve complex problems through human interaction. However, the author contends it is time to update “human interaction” to “intelligent interaction” to account for AI’s unmatched potential to access, process, and store data. The author proposes that when trained adequately with relevant, secured data, AI-assisted Wargaming can enhance learning, accelerate problem-solving, and help prepare humans for competition.

USAF doctrine defines a domain as a “sphere of activity or influence with common and distinct characteristics in which a force can conduct Joint functions.” (The LeMay Center, 2024) After millennia of competing on the land and sea domains, humans developed Airpower over the last century, revolutionizing warfare. However, in the previous decade, we have added Space, Cyberspace, and the Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) as warfighting domains, and our nation is struggling to adjust.