THOUGHT LEADERSHIP COMPENDIUM

ARTICLES BY:

ARTICLES BY:

To solve the most pressing public health challenges, we need to make data accessible to a broader community of researchers—and introduce new ways of working that encourage collaboration and rapid discovery. Here’s a framework to help public health leaders spur meaningful change.

Researchers focusing on public health today have an exciting opportunity to accelerate breakthrough discoveries and tackle the most pressing public health challenges including child and adolescent mental illness, pandemic disease, opioid addiction, gun violence, and many others. By taking advantage of the unprecedented convergence of bigger data, better technology, and a rising cultural shift toward greater collaboration and sharing, we can proactively supercharge advancements in public health.

But the value of this convergence will not be delivered to the passive spectator; researchers, citizen scientists, and curious laypeople must activate and maintain these intersections to release their potential. This requires a fundamental change to the way people relate to data—and to one another.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored our need for data that moves faster than disease.

Scientific advancements are predicated on good data. In some domains—including cancer biology, infectious disease, and addiction research—there can be so much data that it becomes difficult to manage in a way that maintains security and integrity over time. Many public health agencies struggle to manage the large volume of data generated for research or, conversely, are challenged to get enough of the right data into the right hands, to fuel analysis and insights that lead to timely interventions.

Such was the predicament for the National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), which receives large amounts of tumor proteomic data and mass spectrometry data from numerous sources from across the cancer research community. The challenge is to store these data in a central repository that all cancer researchers can access while supporting the reliable, secure, and rapid movement of data.

How can public health leaders create the systems that support breakthrough discoveries—and inspire a culture of scientific collaboration within their organizations?

Carpe datum: Are your data systems and research culture ready for the new era of public health?

In order to conduct real-time infectious disease surveillance, advance cancer research, and develop life-saving public health interventions, we encourage agencies to embrace a three-pronged approach:

Evolve the workflow of research so that sharing data (while ensuring data standards are met) becomes as routine as checking email—this requires combined expertise in health IT, research data management, and scientific disciplines such as epidemiology, genomics and proteomics, and health research.

A critical piece of the solution for grappling with the high volume, variety, and velocity of data lies in the use of data commons. Data commons—or the platforms that store shareable data sets that researchers can manipulate and interrogate with the help of visualization tools, artificial intelligence, and machine learning—help improve the speed and quality of data management as well as ensuring research data is accessible beyond the life of a grant, research project, or individual careers.

2. Harmonize your data/establish standards for data collection, sharing, and integration. This ensures clinical data from many different sources are usable and may be compared across cancer programs. When data is harmonized, public health researchers can explore, for example, how trends may vary between populations and in different geographical areas.

3. Factor data privacy into the solution design. While data sharing provides enormous benefits to the research community, you may require private spaces for individual research teams to exchange data. For the NCI, we created private areas as well as the public PDC portal for distribution of data from collaborators in the International Cancer Proteogenome Consortium.

4. Engage stakeholders in the standards development process. Communication and collaboration are key. Because standards will impact a wide range of users such as measure developers, tool developers, implementers, and those who manage receiving systems, it’s important to engage stakeholders early in the process to ensure the standards meet their needs. For example, ICF supported the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in establishing standards for working with electronic health records, extracting patient information, and assessing clinical quality.

For CPTAC, ICF created the Data Coordinating Center where researchers exchange data and the Proteomic Data Commons (PDC) where anyone can explore the data. These tools work together so that clinical data from many different sources are usable and may be compared across cancer programs. We partnered with the NCI to ensure quality control and security for data transit through encryption and verification processes. We also harmonized the data so researchers could analyze it and draw comparisons with other data sets.

1. Build quality control and security into data receipt. For the NCI CPTAC, we encrypted data in transit and then verified it with a checksum file. Due to this focus on data integrity, researchers can trust that files correctly map back to the right sample and accurately capture the information associated with tumor acquisition.

The importance of these data handling approaches is underscored by the requirement among federal funding agencies that researchers ensure the data they produce adhere to the FAIR (findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability) principles. The FAIR data principles were put forth in 2016 by an international group of scientists, funders, and publishers to encourage the reusability of data given its increasing volume and complexity. While many research institutions around the world have adopted these principles, some struggle to comply. Proper training, tools, and support for sharing and standardizing data can help researchers and program directors ensure compliance.

Build a community of scientists across fields, as well as nonscientists, who can curate, maintain, and evolve the data commons model—and entice them to the table with the promise of data that is open, standardized, credible, elastic, robust, reliable, and FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable).

Carpe datum: Are your data systems and research culture ready for the new era of public health?

Learning to embrace new ways of working is easier said than done; in fact, cultural resistance to change is the primary reason digital transformation efforts fail according to an ICF survey of 500 federal employees. The new generation of workers is multidisciplinary, mobile, and accustomed to using intuitive tools to streamline workflows. Gen Z and millennial workers are more open to trying out “bleeding edge” technology at work as well as incorporating virtual assistants, design tools, and augmented reality/virtual reality applications into their workflow. What they lack in peerreviewed academic publications they may more than make up for in diverse perspectives, creative thinking, and collaborative mindsets. Public health leaders can cultivate enthusiasm for new ways of working by implementing interdisciplinary teams and empowering staff to become change advocates.

5. Develop favorable interpersonal conditions. Ensure team members have a shared understanding and expectation of trust, respect, openness, communication, and learning.

6. Provide sufficient scaffolding. Teams require continuous process improvement, a culture of continual learning, and other support to help build the foundation required for robust and sustainable collaboration.

7. Grow the team’s skills. Encourage team members to not only develop their expertise but also cocreate new ideas and approaches with others.

8. Empower staff to become change advocates. Identify influential users who can explore new technologies like data commons and bring back information to their teams to generate excitement among colleagues.

Get comfortable with new tools that automate data collection and leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning to surface patterns and insights for researchers to explore in the service of their research objectives—and inspire researchers to embrace the art of the possible through dynamic training and change management approaches.

Specialized data commons, like CPTAC, provide critical functions to the research community. Data commons focus on meeting the needs of researchers within a certain public health domain and their discrete data challenges.

Because of the ethos of data commons, these forums are fertile ground for behavioral and cultural change. They will ease the transition that public health research must make away from the long-standing incentive structure of science, which revolves around publishing in peer-reviewed journals. As more experts and non-experts become familiar with these tools, the fundamental value of sharing data—and making it widely available as part of the scientific democracy— will become apparent.

9. Invest in data collection abilities and domain experts to understand the relationships within the data. Successful health IT implementations require partners who know how to bring science and technology together. In collaboration, these experts can train new tools to provide a mathematical representation of the real world. Once that’s done, anybody in the agency can use it to ask questions of the data.

10. Be smart about how you catalog and inventory all your data assets. Know where they are, who’s using them, and why. A data fabric—a data management architecture that integrates and models data from diverse source systems into an integrated platform for on-demand access—is a cohesive way of connecting a collection of data tools.

11. Look for data connections that rise to the surface. By connecting disparate data sets together in a way that activates metadata, which is data about the data, you can see and understand more complicated relationships—and generate insights that are much more powerful than the data just on its own.

Another powerful tool is the knowledge graph because it can rapidly explore large volumes of data and find relationships between data points and their attributes. For example, the knowledge graph of genome-wide association studies would depict gene mutations and cancer types as nodes or circles in the graph, and relationships between the entities as lines. Knowledge graphs are one of the analytical and visualization tools that could be available within the cloud-based data science infrastructure of data commons.

The future of data commons is more expansive. Just as the data commons that have been developed over the last several years have encouraged public health researchers to push the boundaries of how they work within their domain, there is movement underway to expand the mission of data commons. While bespoke data commons solutions play an important role in advancing agency missions, success depends on enabling individuals to step outside of their comfort zones and unite around the common goal of finding solutions to the most pressing public health crises.

Data commons are coming that house any matter of data type and allow any number of discovery activities. These forums will answer the need of every individual who works with, and thus struggles with, data—whether they are a leader at a federal health agency, a member of a research team participating in a consortium, a healthcare professional, a director of a funding agency, or a policymaker. And by bringing diverse sets of data together, individuals can test hypotheses in minutes that may otherwise require year-long studies.

We partnered with a major cloud service provider to create a flexible data commons solution as a demonstration of a next generation data commons. In partnership with Amazon Web Services (AWS) Envision Engineering group, we created an automated, userfriendly environment to import, store, explore, and analyze data using AWS cloud technology. The goal for this tool is to allow researchers to collect, store, and share high-quality data and collaborate in the service of breakthrough discoveries, especially in realms where data poverty is a known problem. Mental health. Gun violence. Rare diseases.

If researchers can engage with a larger, harmonized, and accessible data environment, they can support the objectives of their own research, while simultaneously enabling the research activities of others.

Such high quality, standardized data would also pave the way to grow the applications and benefits of artificial intelligence and machine learning in public health research. For example, recent advances in natural language processing, a subfield of artificial intelligence, are enabling rapid analysis and data extraction from scientific literature, health records,

social media, and other documents. This could lead to faster identification of diseases and more efficient evaluation of the safety of disease prevention strategies. Similar tools would be able to automatically analyze data as they are entered into a data commons, allowing for unbiased data exploration and detection of unexpected patterns between data sets.

By bringing together diverse users and datasets, tools, and predictive modeling, we’re creating a dramatically different model of data sharing from what previously existed, providing democratic access to data in an interface that is portable, lightweight, scalable, and elastic. Cloud-based data environments create access to relevant data sets in a way that rewards “out of the box” interdisciplinary public health research and thinking.

Public health research requires a vast array of data to identify patterns, trends, and associations. By providing support around data management, workforce transformation, capacity building, and industryleading digital solutions—we can help agencies get the data they need to draw connections in their data and make important public health decisions. Adopting this new approach for data handling, sharing, and standardization would represent major strides toward ensuring that the impressive quantity of public health data is matched in quality.

Federal agencies have access to massive amounts of data that could transform how they interact with and support the citizens they serve. But before agencies can unleash the full potential of their data, it is essential that agency leaders establish comprehensive strategies for effective data use and management.

In its review of the Federal Data Strategy, the U.S. Chief Information Officers Council notes that government leaders need “a robust, integrated approach to using data to deliver on mission, serve customers, and steward resources while respecting privacy and confidentiality.” By focusing on five key areas, each of which requires its own established strategy, federal technology leaders can lay the groundwork for an enterprise-wide data strategy that will power evidence-based decisions, improve operational efficiencies, enhance customer service, and more.

An agency’s data governance strategy is the essential framework that will guide its overall data management. In developing a comprehensive data governance strategy, agency leaders are encouraged to assess all roles, responsibilities, and policies related to how their organization handles data. Overly complex or rigid strategies can create roadblocks.

“There can be so many layers associated with governance that it becomes tough to navigate, which could stagnate your ability to move data forward. You need to make sure you have good decision-making strategies in place to avoid stagnation while also maintaining the

flexibility to be nimble in your processes,” says James Bench, vice president of technology consulting services at Maximus. “And you need to have the right decision-makers who will take into consideration key issues that could put an organization at risk, especially regarding regulatory and data privacy concerns.”

To mitigate regulatory, privacy, and legal concerns, agency leaders should consider how to support metrics around data quality indicators, how to manage data risk and privacy metrics, and what data elements are most important to the agency’s mission. Such questions are at the heart of Maximus’ approach to data governance, which focuses on implementing and maintaining scalable, secure data architectures while keeping an organization’s long-term goals and technical strategy in mind.

“Having clear, mission-focused principles to guide governance decisions is critical so that value and outcomes don’t get overridden by oppressive processes,” Bench says, “because not every best practice is the right practice in every situation.”.

Since the early days of modern data management, many organizations have relied on data warehouses to store information. The essential concept of a data warehouse — a term coined by IBM researchers in the 1980s — is a place to centralize your structured data. By creating this single source of truth, an organization could ensure that anyone building analysis or reporting based on that structured data knew that the quality was dependable.

While this way of maintaining data quality was standard for years, the sheer amount of data and the number of sources that organizations juggle in the present era of “big data,” has reduced the efficiency of data warehouses. Their structured nature leads to a level of rigidity that can make maintenance and upgrades difficult and costly. These complications have led organizations to seek other options for standardizing quality.

“You shouldn’t have to wait for a full, laborious requirements process or cleansing process to get data in your hands,” Bench says. “But that also shouldn’t preclude you from being able to come up with a good data quality strategy for the strategic information that you want to maintain and keep as one version of that particular truth.”

Essential data quality considerations include: Is the data accurate? Is it complete? Is it consistent? Is it timely? Is it unique?

“You can still tag data quality metrics to every single data source, and that allows for data consumers throughout your organization to at least have a good understanding about what they’re about to consume,” Bench says.

Even if data isn’t perfectly clean, “having quality metrics puts the right caveats in place, so it’s taken with an eyes-wide-open understanding,” Bench says. This includes accepting that data isn’t objective and knowing that potential biases or ethical skew in the source data may produce similarly biased analyses.

“As people consume that piece of information, there should be layers of understanding about what they are looking at,” Bench says. “For example, is it skewed? How was it created? Where was it originally created from? And what has happened to that data between when we sourced it and when data consumers access it?”

After assessing data quality protocols, the next step is to review existing data integration strategies. For example, where will data be combined and stored across the organization?

“Is it going to be a data warehouse? Is it a data lake? Is it a data lake house or a data mesh?” Bench asks. “Ultimately, the data integration strategy should be based on what your enterprise needs and whether you want centralized or decentralized ownership of data.”

Data warehouses are a centralized place to store structured and curated data and serve as a single source of truth. Data warehouses typically follow extract, transform, and load (ETL) data integration processes.

Data lakes

like warehouses, are centralized places to store data. However, unlike warehouses, data lakes store all forms of data, including raw data in its original format. Data lakes offer increased flexibility and agility than data warehouses, but potentially less quality assurance. Data lake integration processes follow the same steps as data warehouses in a different order: extract, load, transform (ELT).

Data lake houses are a hybrid concept that combines the best of both worlds. It marries a data lake’s ability to store both structured and unstructured data with many of the data governance and cleansing protocols associated with data warehouses.

Security is ensuring that you understand both the risk profiles of your data and your access control policies really well. This is why good auditing practices are important; you can see who accessed the data and when, as well as understand the state the data was in at that time it was accessed.

JAMES BENCH Vice President Technology Consulting Services

Data meshes

are a more recent concept that takes a decentralized approach to data management. Rather than an enterprise-wide repository, individual business domains host their own data. Each domain is responsible for maintaining its data and making it accessible to the rest of the organization.

A strong data integration strategy doesn’t necessarily require an organization to pick just one of these options.

In a data mesh approach, for example, individual business units could still employ their own data lakes or warehouses.

“In most cases, you need a mix,” Bench says. “But there are tradeoffs you have to consider when developing your data integration strategy, because the investment in time to get value varies wildly between which integration strategy you build.”

Consider the flow of data through an organization as a pipeline. If data integration

informs the flow of data into your chosen repository — whether warehouse, lake or mesh — the data analytics process happens when that data leaves the repository. At a high level, an analytics strategy involves establishing what business decisions an organization should make based on its data.

“Historically, analytics have primarily been used for reporting, providing insights through operational reports, or trending and analysis reports,” Bench says. “Today, many agencies use data for statistics work, AI, and machine learning projects.”

Of course, the quality of analytic outcomes will depend on an agency’s data quality. No matter how good an analytic model is, bad data will result in flawed decision-making. A good data analytics strategy will outline prerequisites, such as traceability, source transparency and clear communication about any potential caveats or biases in the data.

“The key is to question validity constantly. You need to understand the accuracy of your analytics when making decisions.” Bench says. This is where associating quantitative metrics

is beneficial; you can see how your analytics are trending over time.

Security is always a top priority for government agencies, and the best security practices strike a balance between protecting sensitive information and maximizing informed decisionmaking.

“The most secure system is the system that is not plugged into a wall, but once it’s plugged in, everything becomes accepting a certain amount of risk,” Bench says. “Data is the same way, in that the safest way to protect it is to ensure no one has access to it.”

However, data security is not about eliminating risk but rather it’s about determining how much risk is acceptable and for what gain.

Risk analysis starts with establishing the “what” and the “who” of data access:

1. What data elements, or what combinations of elements, present privacy concerns? For example, one piece of information may not be sensitive by itself but becomes sensitive when coupled with other data.

2. Who is allowed to access each element? What is the criteria for this decision?

“If only two elements of privacy concern are blocking a whole data source from being shared, that is a missed opportunity,” Bench says. Luckily, data management tools have reached a level of precision that makes it possible to access and use data in targeted ways.

Technology leaders can now build policies and implement tools that are sophisticated enough

to maintain that optimal balance of security and flexibility by granting a range of very specific levels of access.

“Security is ensuring that you understand both the risk profiles of your data and your access control policies really well,” Bench says. “This is why good auditing practices are important; you can see who accessed the data and when, as well as understand the state the data was in at that time it was accessed.”

While each federal agency is at a different point on the road to using data as a strategic asset, they share a common goal of increasing collaboration between agencies. In fact, the Federal Data Strategy advises agencies to “assess and proactively address the procedural, regulatory, legal and cultural barriers to sharing data within and across federal agencies, as well as with external partners.”

Working with partners like Maximus on creating a data governance strategy, understanding the quality of data and analytics, and being deliberate about integration and security choices can assist agencies in breaking down those inter-agency silos. However, Bench also acknowledges that hurdles to interoperability are not necessarily technical.

“It’s a regulatory issue, it’s a privacy issue,” he says. “Better labeling of data, identifying which areas are actually sensitive and not sensitive, and creating interoperability so you can share that data, those are areas that could move a lot further and faster in the public sector.”

Introduction

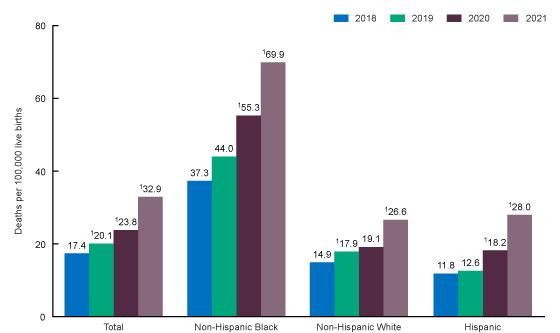

Maternal mortality rates in the United States remain alarmingly high compared to other countries. In 2021, the U.S. maternal mortality rate was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 births rising from 23.8 in 2020 and 20.1 in 2019 (Hoyert, 2023). The significant racial and ethnic disparities reflected in these rates are well known. In 2020, Black women were more than two and a half times more likely to die from pregnancyrelated causes than White women (CDC, 2022) In fact, Black women are more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death in the U.S. than in any other developed country. American Indian/Alaska Native and Hispanic women are also at increased risk of pregnancy-related death compared to White women. These persistent disparities underscore the urgent need for interventions to address the root causes of inequities in maternal health outcomes. These rates are indicative of the significant impact of social determinants of health on maternal outcomes.

The disproportionate impact on communities of color underscores the systemic racism and structural inequities that perpetuate health disparities. Racial and ethnic minorities often experience barriers to accessing quality maternal health care, such as inadequate insurance coverage, geographic isolation, and lack of transportation (Kozhimannil et al., 2019). Additionally, issues such as poverty, inadequate housing, and food insecurity are strongly associated with poor maternal outcomes, highlighting the need for comprehensive interventions that address these social determinants of health that contribute to poor maternal health outcomes (Metz et al., 2017). These disparities must be addressed through culturally responsive care and interventions that are tailored to meet the unique needs of vulnerable populations, including people of color and lowincome people.

Although barriers to accessing quality maternal health care disproportionately impact women of color, it is important to

note that even among people with access to quality care, significant racial disparities in maternal mortality persist. Furthermore, Black women with high levels of education and income had a higher risk of maternal death compared to their White counterparts with lower levels of education and income. For example, Creanga et al. (2018) found that Black women with college degrees were more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than White women without a high school diploma.

Other studies have similarly reported that Black women with access to high-quality care experience higher rates of pregnancy-related complications, such as pre-eclampsia and preterm birth, compared to White women (Cavanaugh, 2021). These findings highlight the impact of systemic racism and structural inequities on maternal health outcomes, which can persist even in the absence of traditional barriers to accessing care. Comprehensive and multifaceted interventions that address both the social determinants of health and the systemic racism that perpetuate them are required in order to effectively improve maternal health outcomes.

One effective approach to improving maternal outcomes is the implementation of birth plans among all pregnant individuals. Birth plans are written plans that communicate a person's preferences and goals for labor, delivery, and postpartum care to their birthing team. Birth plans have been shown to increase patient satisfaction, improve patientcentered care, and lower rates of medical interventions during childbirth (Jennings et al., 2018). Equity birth plans (EBPs) utilize a health equity model to address social determinants of health that can impact maternal and infant health. Utilizing the socio-ecological model (Armstrong et al., 2007) as its framework, equity birth plans center the individual in the consideration of integrated patient-related and systems-related risks to achieve safe and equitable birth outcomes (Tyre et al., 2022). Such considerations include individual patient experiences, fears, and concerns, and access to clinical, familial, and community support resources (Tyre et al., 2022).

Equity birth plans are culturally responsive and have demonstrated the efficacy of birth plans in improving maternal and infant health outcomes among people of color. Howell et al. (2020) reported that the implementation of birth plans in hospital settings led to a significant reduction in preterm birth (from 13.8% to 9.9%), low birth weight (from 12.6% to 7.7%), and infant mortality (from 2.6% to 1.9%) among Black women. Kozhimannil et al. (2016) found that birth plans that included doula support and group prenatal care were associated with a 41% reduction in preterm birth and a 33% reduction in low birth weight among women of color. Moreover, equity birth plans that address the unique needs of Black people and other birthing people of color have been proposed as a promising approach to reducing racial

1Statistically significant increase from previous year (p < 0.05). NOTE: race groups are a single race. SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.and social inequities in maternal and infant health outcomes (Tyre et al., 2022).

As a component of their birth plans, a growing number of pregnant people are opting for alternative birth settings as another strategy to improve their birthing experiences and overall maternal health outcomes. Advocates for out-ofhospital births argue that these options can provide a more personalized and culturally responsive birth experience, as well as greater autonomy and control for the birthing person. In 2019, out-of-hospital births accounted for 1.61% of all births in the United States; a slight increase from 2018, when out-of-hospital births accounted for 1.5% of all births (Martin et al., 2021). Of the 64,504 out-of-hospital births that occurred in 2019, 35,426 occurred at home and 29,078 occurred in free-standing birth centers.

difficult to access out-of-hospital birth options (Tilden et al., 2014).

Despite these barriers, efforts are underway to increase access. As of 2021, several states have Medicaid programs that cover doula services, including Oregon, Minnesota, and New York (The National Partnership for Women & Families, 2021). These programs provide reimbursement for doula services, which can help to make these services more affordable for low-income women. Additionally, some nonprofit organizations and community groups are providing free or low-cost doula services to women in need (Hudson, 2018). In addition to doula coverage, some state Medicaid programs also cover midwifery services; Medicaid coverage of midwifery care has been associated with lower rates of preterm birth and cesarean delivery (Kozhimannil et al., 2014). In Oregon, Medicaid covers licensed midwives who provide care to pregnant women and attend home births (Oregon Health Authority, 2020). In New York, Medicaid covers midwifery services provided by certified nursemidwives (New York State Department of Health, n.d.).

Out-of-hospital birth can play a particularly important role in improving birth outcomes. Although the majority of these alternative settings have been experienced by non-Hispanic Whites, there is growing interest and demand for out-ofhospital birth options, particularly among women of color and those with a history of traumatic birth experiences or medical interventions (Pascali-Bonaro & Anderson, 2021). Planned home births attended by certified professional midwives are associated with good outcomes for Black women, including low rates of interventions and high rates of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) and breastfeeding initiation and continuation (Cheyney et al., 2014). Black women who planned to deliver at home or in a birthing center with a midwife had lower rates of preterm birth and low birth weight compared to Black women who planned to deliver in a hospital with a midwife or physician (Grünebaum et al., 2017).

Despite their positive influence on maternal outcomes, access to midwifery care remains limited for vulnerable populations in the United States. (Stapleton et al., 2018; Kozhimannil et al., 2016; Kozhimannil et al., 2019). Midwife shortages exist in many parts of the country, and where available, midwives may not be licensed to practice or attend births (Groppe & Zuppa, 2019). Doulas, who provide emotional, physical, and informational support to pregnant women during labor and delivery, are also less accessible for some – people of lower socioeconomic status (SES) and people of color are less likely to have access to doula care compared to their counterparts with higher SES (Kozhimannil et al., 2016). This is due, in part, to the cost of doula services, which can be prohibitive for some families In addition, most insurers do not cover doula care Similarly, out-of-hospital birth options, such as home birth or birth center births, are less accessible to people of lower SES and people of color. This can be due to a lack of insurance coverage for out-ofhospital births, or limited options for out-of-hospital births in certain regions. Some pregnant people may also face barriers related to transportation or childcare, which can make it

Other efforts include increasing the number of midwives in underserved areas, providing education and information about midwifery care to women and healthcare providers, and promoting the use of midwifery care in healthcare policies and guidelines (Bingham et al., 2018; Snow et al., 2017). It is critical to prioritize the implementation of birth plans in a way that is equitable and accessible to all pregnant/birthing people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. While there is evidence supporting the effectiveness of developing and implementing EBPs, which may include the use of a doula or midwife, and/or the consideration of out-of-hospital birth settings, these interventions are less likely to be promoted among people of lower SES, people of color, or people who are of higher risk.

Role of Community-Based Organizations (CBOs)

Community-based programs can play an essential role in improving maternal health outcomes, particularly for pregnant people who experience social and economic disadvantage, by supporting the development of birth plans, promoting out-of-hospital births, and advocating for policy and systemic changes to improve access to equitable perinatal care and support. CBOs work to address the social determinants of health that impact maternal and infant health outcomes and improve access to healthcare, education, and other resources.

CBOs can support the development of birth plans by providing education and resources that empower pregnant people to make informed decisions about their care. A community-based program in Hawaii that provided group prenatal care and individualized support improved birth outcomes and increased maternal satisfaction with care. The program promoted the development of birth plans and empowered participants to make informed decisions about their care (Hsieh et al., 2020). A community-based, free standing birth center in Minnesota (Hardeman et al., 2020) utilized a culturally-centered model of pregnancy and postpartum care people to address the disparities in birth outcomes experienced in their community, resulting in zero preterm births experienced among the 284 families that participated in their programs.

CBOs can also play a role in promoting out-of-hospital births as a viable option for pregnant people. Holzman et al. (2020) found that a community-based program that provided

group prenatal care and education increased the likelihood of planning an out-of-hospital birth among participants. The program also provided support and resources for those who chose to have an out-of-hospital birth, which contributed to positive birth outcomes.

CBOs can also advocate for effective policies that support pregnant people. The National Perinatal Association's Community-Based Doula Program works to improve access to doula care for low-income and marginalized communities, advocating for policies that support doula care and providing resources and training for doulas. The program has been shown to improve birth outcomes and increase maternal satisfaction with care (Nommsen-Rivers et al., 2021).

Policy Implications and the Federal Response

State Medicaid programs can impact access to perinatal care by covering non-OB providers and staff, such as certified nurse-midwives, doulas, and community health workers. The Oregon Medicaid program covers doulas as part of its maternity care package, resulting in reduced rates of preterm birth and cesarean section (Ward et al., 2019). Similarly, the Medicaid program in New York City provides reimbursement for community-based doula services, resulting in improved maternal and infant health outcomes among low-income women of color (Ickovics et al., 2020).

Public policies can also impact maternal health outcomes by addressing systemic issues such as racism, poverty, and lack of access to care. The Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 is an example of federal legislation aimed at addressing racial disparities in maternal health outcomes by providing funding for various programs and initiatives, including maternal mental health services, perinatal quality collaboratives, and implicit bias training for healthcare professionals (Ely, 2021).

There are, however, concerns about the safety of out-ofhospital births. While planned out-of-hospital births were associated with lower rates of interventions such as cesarean section and epidural anesthesia, they also had a slightly higher risk of perinatal mortality and neonatal seizures compared to hospital births (Grünebaum et al., 2017). In addition to concerns about safety, there have been cases of criminal prosecution of families who experience complications during out-of-hospital births, particularly in cases where the family did not seek timely medical attention or did not disclose their plans for a home birth to their

healthcare provider (Lavender, 2020). Funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) can support workforce development and research on strategies to improve maternal health outcomes. HRSA provides funding for nurse-midwifery education programs and the National Health Service Corps, which places primary care providers in underserved areas (CRS, 2021). CDC funds the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), which collects data on maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy to inform public health interventions and policies. By investing in research and workforce development, policymakers can improve access to care and support evidence-based practices that promote maternal health equity.

Summary

Efforts to improve maternal health and birth outcomes must address systemic issues such as racism and lack of access to quality care. Equity birth plans and out-of-hospital births are promising strategies for promoting maternal health equity and reducing disparities in birth outcomes, particularly among Black women and other women of color. By addressing social determinants of health and promoting patient-centered care, these strategies can improve access to high-quality care, increase patient satisfaction, and reduce the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

However, there is still a lack of awareness and education about the benefits and risks of out-of-hospital births, particularly among socially and economically disadvantaged populations. Public policy makers and public and private partners are increasing messaging, education, and awareness about birth setting options to ensure that individuals have the knowledge and resources to make informed decisions about their care. Funding for community-based organizations and programs that prioritize equity in maternal health can also help address these issues and improve outcomes for all communities.

As researchers, clinicians, and public health professionals, we have a collective responsibility to promote maternal health equity and ensure that all individuals have access to safe, high-quality care. We must continue to advocate for policies and programs that prioritize equity in maternal health, and work towards increasing messaging, education, and awareness about birth setting options, particularly among marginalized populations, if they are to thrive!

As a long-standing stakeholder in helping to advance U.S. public health outcomes, The MayaTech Corporation is deeply committed to our nation’s health – with a keen eye on addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) and reducing systemic barriers that result in health disparities and inequities. Tackling the coming weeks, months, and years will require dynamic partnerships among all sectors to ensure that Federal public health initiatives are effective, efficient, and reach the communities most in need.

The MayaTech Corporation addresses existing and emerging public health challenges through direct engagement with agencies, governments, foundations, institutions of higher education, the private sector, communities, and individuals. We provide a portfolio of research, training, evaluation, capacity-building, and other strategic support services - all aimed at reaching and impacting the most vulnerable populations, amplifying best practices, and innovating the practice of public health.

MayaTech's recent work has included support of Federal agencies and their grantees for stakeholder-engaged projects aimed at: identifying barriers to HPV vaccination in rural communities; advancing racial equity and researcher diversity in artificial intelligence and machine learning to reduce health disparities; evaluation of research infrastructure capacity at HBCUs to address maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS, and cancer disparities; and building workforce capacity among underrepresented minority researchers, health providers, and trainees.

© 2023 The MayaTech Corporation