7 minute read

Pasos

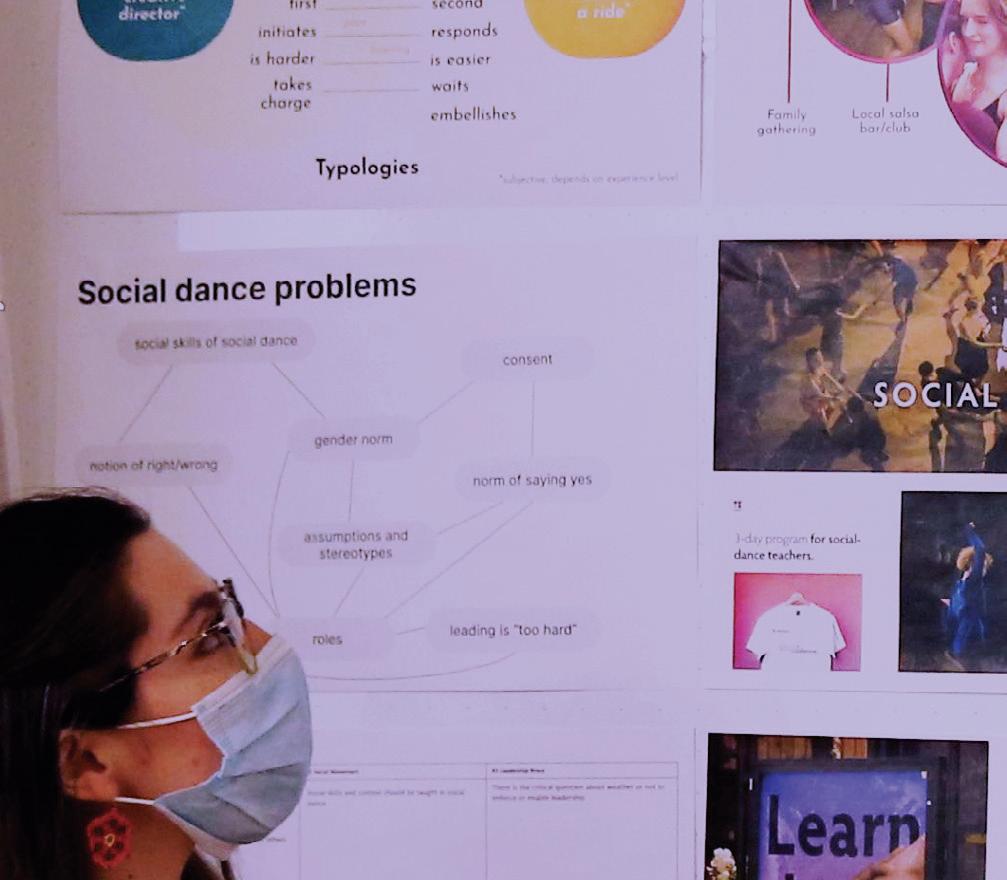

Design Intervetions for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance

MONICA ALBORNOZ

MFA Products of Design

School of Visual Arts

Pasos: Design Interventions for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance.

1st Edition © 2023 Monica Albornoz

Written, gathered and designed by Monica Albornoz.

Created as part of the author’s master’s thesis in Products of Design at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

This work is licensed under the creative commons attribution, noncommercial, no derivatives, 3.0 unported license.

Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Noncommerical — You may not us this work for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

“If

To Ben, who encouraged me to pursue the dream of design in the first place.

For your super-human listening ear and tireless support, for your many homecooked meals and little favors. For giving me perspective when I needed it most and for holding me up when I thought I could give no more. But most of all, for nurturing my wish to lead in dance, for asking me to lead you, and for pushing me to snap out of the fear and dare to lead.

To the dancers, teachers, and organizers I spoke with for this thesis.

For your precious time. For your openness in discussing the confusing paradoxes of the partner dance experience. For inviting me to your events and classes, and for giving me a privileged look at your methodologies, strategies, and business structures. For confiding in me your dance dreams and your personal stories, for pouring out your anger and frustrations, and for reminding me— through your passion—that dance is life, and that’s why we need to do better.

Contents

Isummoned all my courage and came over to Juan. “Do you want to come to dance lessons at my house?” I asked, trying to sound chill. “Lala and Cami are coming tomorrow. It’s fifty thousand pesos for an hour-long class.” Juan muttered some version of “...Maybe next week.” He had soccer practice.

Enrique, the dance teacher my mom had found for me, had encouraged me—now for multiple weeks in a row—to ask my male friends to come over for our afterschool dance lessons on Tuesday afternoons. My friend Simon had joined once or twice, but we needed more boys. We needed more boys because Gabriela, Camila, and Laura would often join me for class, and this meant that, as Enrique danced with one of us, the other three held invisible partners in the air while doing the basic step.

I remember the quiet frustration and anticipation of waiting for my turn to dance with Enrique. When I danced with him, it was impossible not to smile. I could feel his charisma, his sazón (read: Spanish for “characterful flavor”), the music made physical through the moves he guided me on. I loved the heightened sense of attention that dancing asked of me and the endorphins I felt when moving rhythmically to my favorite music alongside someone else. Dancing was pure, freeing pleasure. But it was a pity: Having my girlfriends over came at the cost of partner dancing with Enrique, and the quinceañera parties for which I was learning to partner dance in the first place severely lacked boys who knew or wanted to partner dance at all.

I remember eagerly arriving at my first quinceañera party clad in heels and a short dress, eager to put my dance moves to use, maybe turn some heads, hopefully get a date. To my dismay, whenever the DJ played salsa and merengue seemed to be the de facto sit-down break time for the boys. All that fist-pumping to EDM hits of the early 2010s was exhausting, after all.

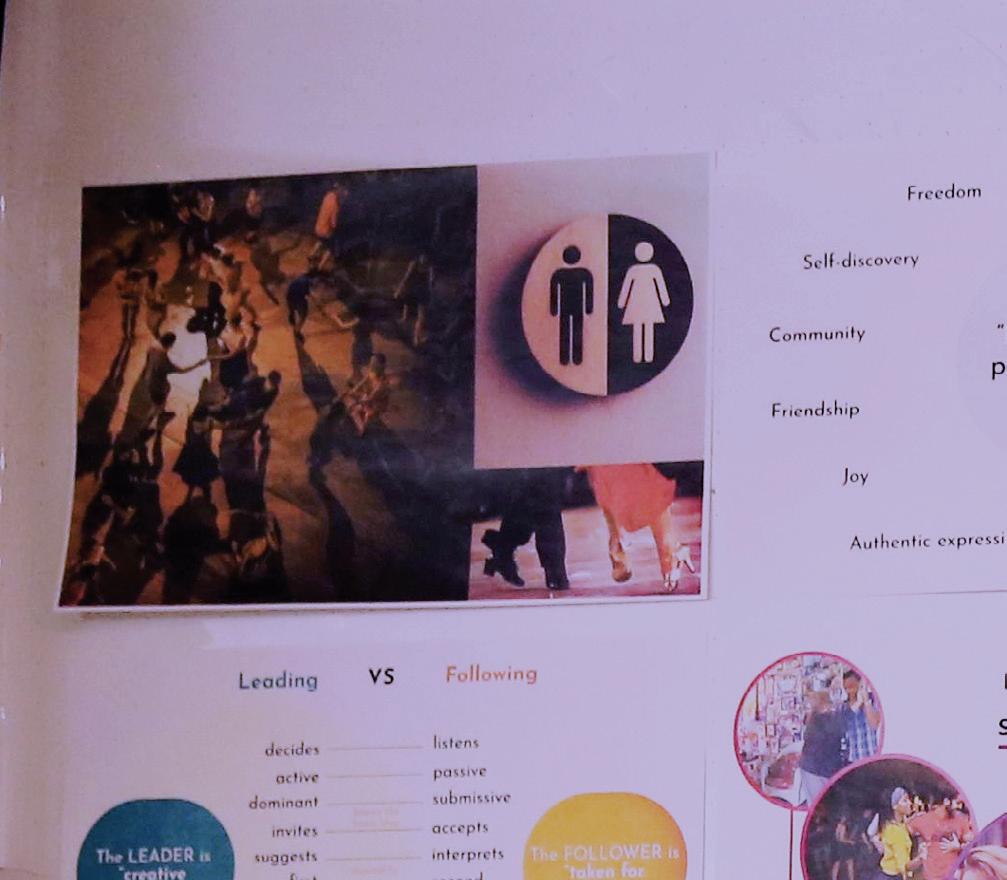

I used to label it as unfortunate that I didn’t have many male friends to invite to dance lessons as a 14-year-old. Thirteen years later, I know better. What is unfortunate is the pervasiveness of a culture that teaches men to lead and women to follow. How much are girls and women missing out on as they sit on the sidelines waiting for men to enable them to do what they love?

Not once during that year of learning partner dance with Enrique did it occur to me to turn around, grab a fellow girlfriend and lead. Nor did it occur to them. How could that be?

Seventeen years later, it’s hard to express how much I wish that Enrique had taught me to lead partner dance. As you read through this thesis, I hope you will understand why.

FOREWORD finding my dance shoes

Everything I knew about partner dance began to change in January of 2017 when a friend took me to a “Latin night” at the Soda Club, a four-story dance club in Berlin’s popular Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood. I was expecting a full-on dance club, loud and dim, where we’d dance a bit, but mostly drink, chat, and be flirted with. What I found was not quite that. In Colombia, drinking and dancing were inseparable. At the Soda Club in Berlin, I never found myself dancing with a drunken partner. In Colombia, a successful dance was one that encouraged your partner to stay with you for songs on end. In Berlin, the sign of a good dance was that the men would let you go after a song or two, but ask you to dance a second time later that night or the following week. In Colombia, you’d never go dancing on your own. In Berlin, people arrived on their own all the time. All in all, in Colombia, partner dance was an excuse or means for something else, social, or romantic, or sexual. At the Soda Club in Berlin, partner dance was an end in itself.

This world that I discovered in Berlin, so different from dancing in Colombia, is what I’m calling the international amateur partner dance space.

I wish I could say that those first six months of dancing in Berlin were everything that my teenage school dances failed to be. After all, at Soda, the boys did like to dance, and they danced pretty well. But I still saw my place in the world, and my place in the world of dance specifically, through the eyes of my 14-year-old self. I sat around waiting to be asked for a dance. I felt sad when the better dancers made eye contact with me but did not extend an invitation. I felt deeply confused and pained when I danced with men who’d swirl me around, much like a toy, but did not make eye contact or smile a single time during the whole song.

After the good dances, I’d feel like I was on a high, endorphins racing and no alcohol needed. But there were one too many times when I felt down, stuck waiting, or wishing that things or people were different.

I shared my pains with my friend Candace, the one responsible for bringing me to Soda in the first place. She was blunt and forward. She said, “You look for the people you want to dance with, and when a new song is about to start, you come over and ask them.” I had no idea that I could ask for a dance until that moment.

As my following skills improved, I got asked to dance more now, and faces and names around the club became familiar. But while some pains went away, new ones came. As a follower, I depended on a great leader to have a great dance. And sometimes, my favorite dancers weren’t around. There’d be nights when I’d feel a huge chasm between the dance experience I desired and the one I was having. Even though I had learned that I could ask for a dance and pursue the experienced leaders, I was still a follower, and following always came after leading.

*

As the teacher yelled, “Change!” to signal the time to switch partners and practice the choreography with someone else, instead of a man, a woman approached me. It was the first time I’d ever danced with a woman. Flat-out surprised, I asked her, “Oh wow, you lead?”

What I felt in the early seconds of dancing with that woman was unforgettable. It’s unforgettable because, five years later, I see those feelings in my followers’ expressions when I approach them after the call to “Change!” in class.

*

I chose to explore gender and leadership in amateur partner dance as my thesis topic because from the moment I danced with that woman in Berlin, my journey into the leader’s role has been harder than I expected it to be. I wanted to understand—why?

What is getting in the way? Am I alone in this experience? And most importantly, what can design do to help?

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION setting the stage

About This Book

This book is a documentation of my master’s thesis process, conducted from September of 2022 to May of 2023.

what is a design thesis?

This thesis is not a traditional academic thesis. In this work, I use contemporary design methodologies to explore the topic of partner dance and offer solutions and provocations to the problems identified.

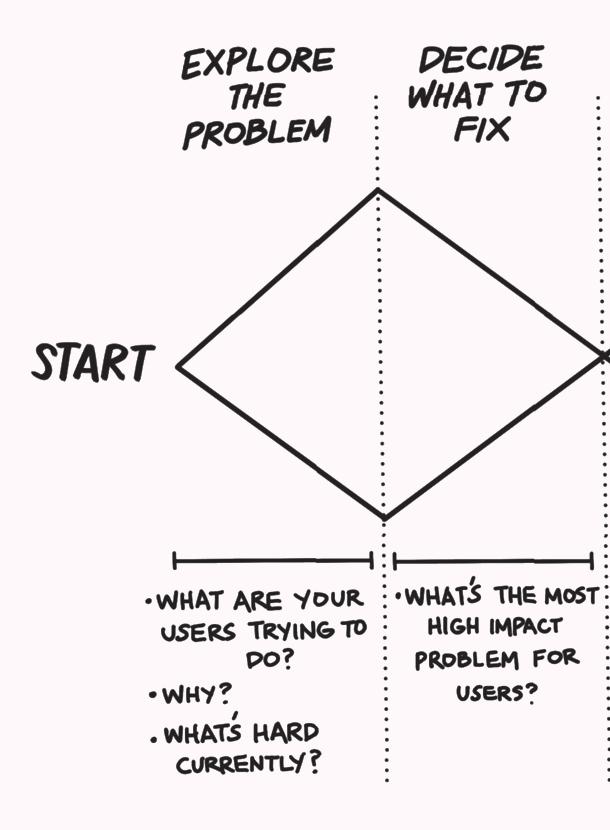

The overarching methodology of this thesis is the double-diamond model of design (see page 24). This model describes design as a process that starts broadly in problem discovery, then narrows down into a specific problem definition. This specific problem then inspires a range of product or solution explorations, which—through testing—re-define the problem and the requirements for more specific, successful solutions.

Alongside the doublediamond, this thesis used rapidprototyping and user-centered design methodologies* to quickly test ideas, engage dancers and stakeholders in the design process, and create safer, more effective, and more ethical solutions. The final outcome of this thesis is not a set of finished objects ready to be launched to market, but a suite of products of design in the form of business models, digital products, services, speculative propositions, experiential engagements, and wearables.