10 minute read

class mechanics mechanics in action

Leaders Followers

Advertisement

(she/her), Latin partner dancer, “Women’s role choices in Social dance” survey respondant role” default, a pervasive mental model in the cosmopolitan partner dance scene, which Juliet McMains, PhD, a professor of dance studies at the University of Washington, introduced to me during one of our talks.

Most of the class is taught without music. This is because it is challenging to hear teachers over the music and because instructors don’t need the music to teach the pattern.

Instructors use “counts” to break down the pattern into sets of moves grouped in eights. Counts are a practical tool for instructors and students, but by removing the dancing from the music, counts also represent the European-leaning view of dance as firstly technical, rather than the Black and streetdance legacy of dance rooted in connection to the music and its emotional interpretation.

Challenges

The single-role structural default of partner dance classes’ design mirrors the gender norm in its binary nature. But it also upholds the gender norm in how it creates challenges for all stakeholders of the experience. Let me explain: It is extremely rare to find an equal number of leaders and followers in a class, but in Latin partner dance, it is exceedingly common that the leader-to-follower ratio leans heavily on the leader side.

This means that when dancers pair up for the pattern, many leaders are left without a follower. Below are the challenges that this creates for all stakeholders.

Stakeholder Challenges

MEN / FOLLOWERS

I’ve rarely seen a cisgender male in the follower role in a Latin partner dance class. From a numbers perspective, they would have an easy time finding leader partners in class. However, due to the stronger homophobia against men as compared to lesbiphobia, men wanting to follow also face barriers towards agency in role choice.

MEN / LEADERS

Men wanting to lead must often bear a portion of the class dancing without a partner. While suboptimal, this is not a terrible hindrance because leaders still get value from practicing the pattern on their own. Followers, on the other hand, don’t get anything from not having a partner in class since their role is responsive.

WOMEN / LEADERS

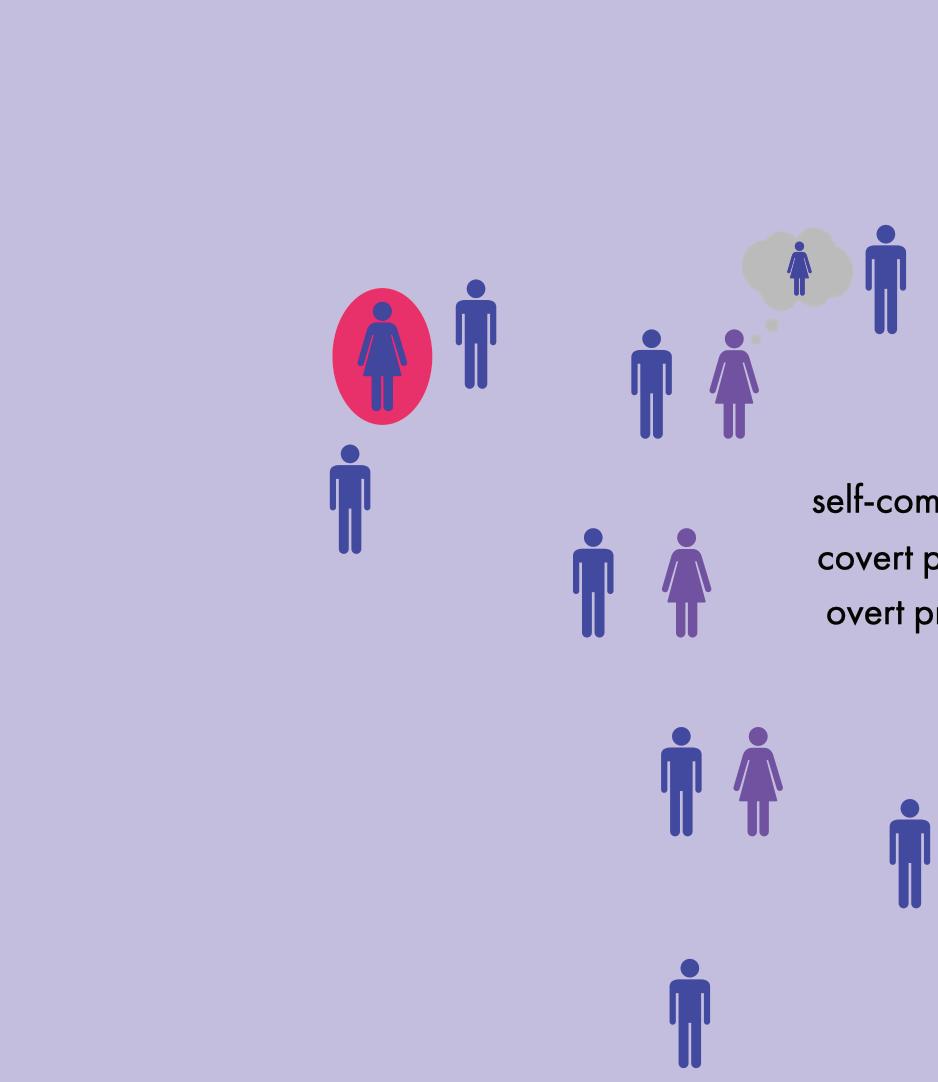

In class, women wanting to lead face the weight of the gender norms starkly. The main issue is social pressure. Social pressure in class can take the form of (1) selfcompliance, where women wanting to lead choose to follow because breaking the norm is so challenging,

(2) covert pressure, such as hearing gendered language from instructors or getting odd looks from fellow participants, and lastly, overt pressure, which takes the form of teachers asking woman leaders to follow during the class to even out the leader:follower ratio; male leaders approaching women leaders without a partner and asking them to be their followers, and men leaders approaching women leaders currently partnered with a woman follower and asking them if they can split up.*

I’d like to note that many of these forms of pressure are not malicious, particularly in a progressive place like New York City. Instructors, organizers, and dancers are simply looking to have a fruitful experience for themselves or for their clients. The problem is that their actions, albeit innocent, draw strong, invisible barriers for the dancers who strive to go against the norm.

WOMEN / FOLLOWERS

Women followers face the fewest challenges in class as they are often in high demand. Because of the responsive nature of following, followers don’t have to and, in fact, are encouraged not to memorize the pattern or to predict what move is coming. This is because partner dance in its true expression is improvisational, and leaders can’t practice improvisational leading if followers “backlead,” meaning, if followers don’t wait for the leaders’ movement cues. In fact this ease turns out to be quite difficult for most beginner followers, who struggle to let go of the notion that they must “know the moves.”

I believe that part of the reason why there is a deficit of followers in classes is that, when followers reach the intermediate stage, they know all they need to know: basic moves and how to follow.**They know that they don’t need to know what’s coming—in fact, that they shouldn’t. So, the class stops being of value to them, and the social becomes a much better place to learn.

Instructors

The instructors’ struggle is to manage a class with many more leaders than followers, which essentially means a product with many less-than-happy clients. I believe that instructors in the Latin partner dance scene either don’t know that a switch-role class is an option, which highlights the need for cross-style community and learning at all stakeholder levels, or they fear that a switch-role class structure will lose them business from cisgendered heterosexual dancers who are not open to dancing with the same sex or in the non-traditional role for their gender.

Emotional Barriers

Outside of class-specific challenges, one of the barriers towards leadership that women face is the belief that leading is “not as

*You wouldn’t believe the amount of times I’ve heard versions of “oh that happens to me in dance class” or “I struggle with that a lot” or “I folded (meaning, gave in to the pressure to follow) the other day”, from women dancers accross many styles of dance.” fun as following” or that it is “too hard.”

**I might have come to this belief based on my conversations with Sabrih Joy Short, an event runner of the Fusion Experience Social, who thinks it’s a problem that instructors only focus on what leaders are supposed to do in class, instead on what followers are supposed to feel.

(9). The emotional stakes grew when women did the same exercise with blindfolds. Aftwer switching, women discussed their experience in both sides of the power balance, and the vulnerability of both roles.

Funness and difficulty are subjective traits. They are not intrinsic to leading or to following. In fact, if leading was not fun, nobody would do it, right? Women have misconceptions about leading because the more they follow, the harder it gets to lead. The one exception here is that when followers reach “expert” level—which for many women is constantly a few months or years of practice away—they feel like they have the mental space to take up leading.

Opportunity

Based on the previous research and insights, I saw an opportunity to improve the following challenges and barriers women face at this stage of the experience:

• Make it a default for women to lead in class.

• Create a space where women don’t feel pressure to follow because of their gender appearance.

• Challenge women’s belief that leading is hard and not fun.

Strategy

• Teach a switch-role class where all participants lead and follow.

• Create a women-only experience free of the gender norm.

• Create a supportive environment where the challenge of leading will be matched with joy.

• Teach the soft skills often overlooked in standard partner dance classes.

• Give women the opportunity to re-think what following and leading are

Process

The development of this project was rooted in theories of embodied experience, which argue that the human body, as our vessel of direct access into the world, is best suited for transformation. While dance is already an embodied action—and while partner dance is an interaction that affords great personal and interpersonal transformation—my challenge was to think about how to design a partner dance workshop that led participants to embodied emotional and cognitive change.

I first developed “movement” sketches to represent the feelings of confidence, freedom, and joy that I wanted participants to access during the workshop. In the process, I realized that confidence wasn’t really the problem, but rather the lack of external support for women to access training in leading. I believed that with support would come skills, and with skills, the confidence would follow. Based on my conversations with dancers and instructors, as well as my personal experience, I broke down the skills that leaders need in order to lead. Unsurprisingly, these went far beyond basic steps and pattern-work. My takeaway was that in cosmopolitan partner dance, the best leading entails both technical and soft skills, and requires a balance of independence and interdependence with followers. It takes two to tango after all. From the follower’s point of view, it’s quite similar. Although the follower is responsive and rests on an unspoken “yes,” or acceptance of the movement cues coming their way, they still have personal agency and the power to communicate a “no.” I didn’t think that followers needed a reminder of their agency and their right to a “no” as much as they needed to experience it in practice. I also thought that this lesson about consent from the follower’s perspective should shift from a right to a responsibility. Because leaders can’t read minds. And it would be risky if we encouraged them to. Teaching followers their responsibilities in a context in which they could appreciate them from both points of view would be a testament to the follower’s bodily autonomy as an equal participant in the endless feedback loop that is the improvisational system of a partner dance encounter.* Partner dance is ripe with these complicated but exciting dualities!

Experience Design

BRANDING

For the look and feel of the experience, I took inspiration from queer brands like lex to design a friendly, proud, but distinctly feminine brand design.

Marketing

I advertised on several partner dance groups in NYC, posted flyers around the city at dance events, and created a free listing on Eventbrite.

Location

Ladies Take the Lead occurred at Solas Bar NYC, a venue in Manhattan’s East Village with a long association with Latin partner dance. Solas Bar hosts partner dance classes and parties almost every day of the week. The dancefloor is accessed through a nondescript curtain in the back of Solas’ main bar. I thought the connection to the Latin dance scene in NYC, the slightly informal nature of the space (without the large mirrors and formality of dance studios), and the threshold of access through the curtain made the location a good choice for the workshop.

TIME

The workshop occurred on Thursday, March 23rd, from 6:30pm to 7:45pm, preceding the weekly 8pm sensual bachata class at the same location.

Audience

The experience welcomed women-identifying dancers of all experience levels.

Experience Journey

The experience was split into three sections: discovery, generosity, and becoming. These sections were capped by an intake form and an outtake reflection. At the discovery stage, participants first learned to tune into their bodies and their interpretation of the music. To aid in this task, they did it while blindfolded. Here, the blindfold was a tool to prevent participants from looking at and comparing themselves to each other’s movement, forcing the eye inwards instead of outwards. Then, participants found a partner and practiced “mirroring,” a touchless form of leading and following with low stakes. I used mirroring as a warm-up into touch-based leading and following. Here, participants simply walked back and forth, for the first time feeling how their bodies could be used to direct others, and be directed by others. To spice things up, participants then repeated this back-and-forth walking exercise with blindfolds on, as the facilitator encouraged them to take note of how they felt in their respective roles and the vulnerability therein. Participants discussed how that experience felt afterwards, as blindfolded followers and seeing leaders.

After these relational exercises, the experience moved on to the discovery of bachata, the style of music that would be used for the rest of the experience.

To introduce bachata, I created a short pre-recorded audio that explained the origins of bachata music and dance, followed by a musical introduction to the five musical components of bachata music, inspired by the classic piece of music, “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra”*, which introduces audiences to the distinctive sounds of each orchestra instrument.

The generosity stage aimed to incorporate the previously learned soft skills into the more standard components of a partner dance class. First, participants learned the basic steps of bachata in a short warm-up, and then learned a short pattern while rotating partners. The large change here was that before rotating partners, a couple would switch roles first, so that everyone got to lead and follow with each other.

The final stage of the experience was becoming, where all the soft and hard skills previously learned had a chance to come together in improvised practice with fellow participants. Here, the facilitator stopped calling out cues to “switch” or “rotate” partners, and participants were simply encouraged to interrupt dances with an invitation to dance with one of the partners.

This improvised practica or mini-social transitioned into a cheering party, where one or two couples dance in the middle of a circle of participants who clapped in support of their fellow women leaders.

The experience wrapped up with a video survey that asked dancers three questions:

• React to the workshop in three words.

• What’s ONE thing you’re taking away with you today?

• Do you think differently about leadership now vs. when you walked in?

These were accessed through a QR code on a take-away card showcasing the experience’s branding and the inspirational quote from the beginning of this book.

Outcomes

Participant and collaborator reactions were positive. They described a great energy, and feeling better than when they came in. The participants who joined from the bar asked if the workshop was happening again in the future.

From the video survey responses, participants used the following words to describe the exprience: “fun,” “challenging,” “energizing,” “safe,” “consent,” “thoughtprovoking,” and “enlightening.”

Personal reflections on leadership included Valeria’s, who said that “[she’s] capable of leading and should have more confidence to continue to do so.” Nihaarika, a firsttime partner dancer, learned that “leadership is not just about being in charge, it’s about being a really good listener.”

Future Considerations

While reflecting as a group after the official end of the experience, it came to my attention that brand new dancers wondered what it might be like to lead a man.

As I departed from the venue, two men at the bar who were waiting for the Thursday night bachata class asked me if I would do a workshop for men.

These two points make me believe there is an opportunity to create a similar experience with switch-role mechanics that is open to dancers of all genders, OR to create an experience with singlerole mechanics where women lead the whole class and men follow the whole class. I think that testing these class dynamics in a safe and supportive enviornment might be even more enlightening, humbling and transformative for individual dancers and the Latin dance community at large.

BARRIER: LACK OF SUPPORT