EDITOR’S NOTE

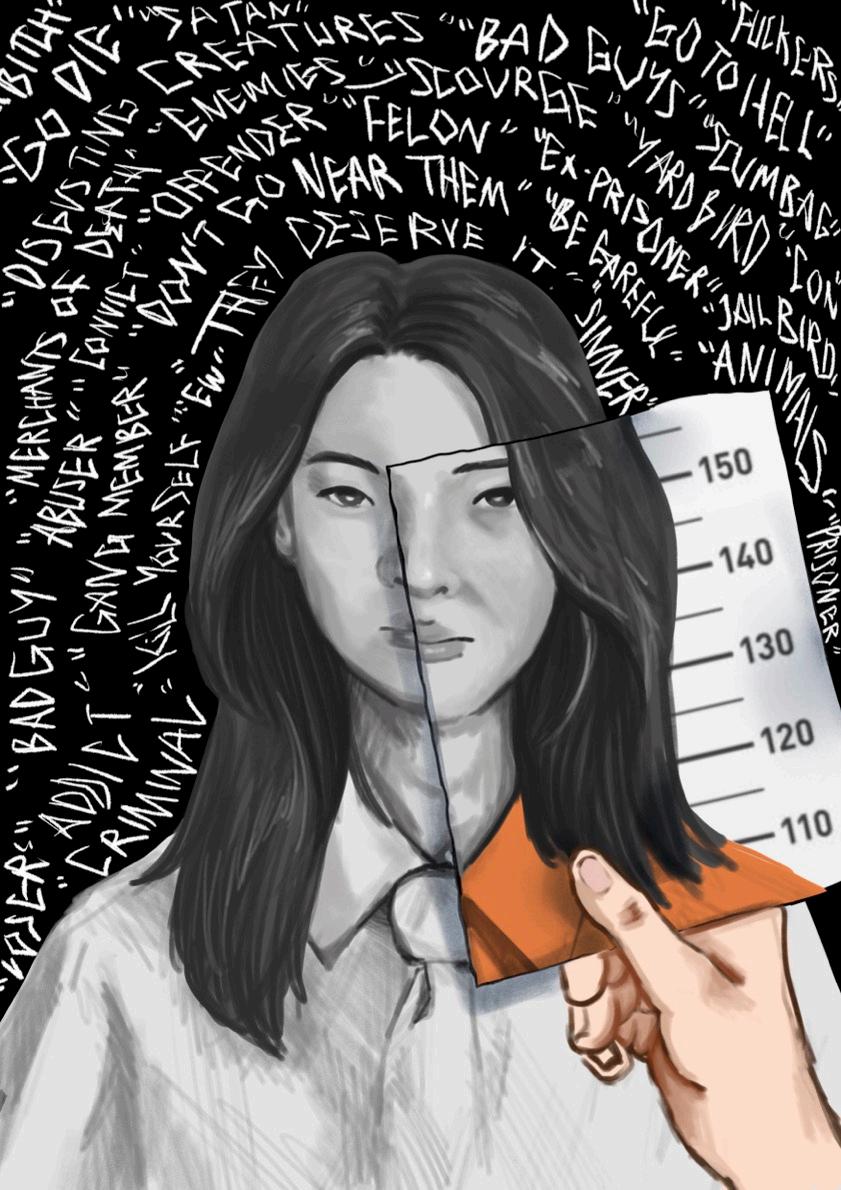

Imagine the worst mistake you’ve ever made now imagine that mistake defining your life forever For many formerly incarcerated individuals, this isn’t a thought experiment It’s the reality they live with every day.

I grew up believing in the power of stories stories that challenge assumptions, soften judgment, and offer the kind of understanding facts alone never can. But as I began to look more closely at how society views those with criminal records, I noticed something deeply troubling: we often reduce people to the worst thing they’ve ever done We forget they are also parents, children, survivors, dreamers. This magazine began with a question: What if we actually listened?

I spent months reaching out to prisons and reintegration organizations across Asia starting in Singapore, where I lived I distributed printed surveys to inmates through a prison warden I had a connection with. Many responses were brief two or three words at most. Others, shared through phone interviews, unfolded slowly, across one-minute calls or two-hour conversations I spoke with someone on death row in Indonesia I read court transcripts in Chinese prisons. Some people joked to mask their pain. Some didn’t want to talk at all But others quietly, cautiously opened up

Their stories weren’t always dramatic. Most weren’t headline-worthy. But they were real. They told me about regret and numbness, loneliness and memory, the aching desire to reconnect with a child, a home, or a former self. A man wept in front of the house he no longer recognized. A woman recounted the moment she realized her son might never forgive her Another remembered the small, specific joy of eating water spinach

Once I gathered these stories pieced together through voice, text, and handwritten notes I didn’t want to simply reproduce them So I asked writers and artists to choose the ones that moved them most, and respond with a piece of original work: a poem, a short story, an illustration, or a collage This magazine is the result of that collaboration a collection of interpretations, not interviews Stories reimagined not to sanitize the past, but to reclaim something more fragile and often forgotten: dignity.

This magazine doesn’t ask you to forget crime. It asks you to remember people. It asks you to imagine mercy alongside justice. It asks you to listen

And above all, it asks you to stay just a little longer with the stories we’re so often told to look away from

I have a lot of feelings associated with my desire to build myself I have a lot of feelings about reintegrating into society better than I was before I was ever incarcerated. There’s a lot of things that I want to share with my children e i ll d I h believe in me I don’t want them to count me out I want have a question and I want to be able to provide them that they need to be successful in life I don’t want them through. I want them to be enough. I want them to leav live on. Even though I’m scared, I’m determined becaus placed in my heart and in my mind for a reason ”

---Femal

Ruixi Chen

Hannah Kwon

Anvvika Vadlapatla

Junyi Lim

Alysa Wu

Jessica Thalita

Maggie Yong

Estelle Zhang

Sophie Wang

Daniel Song

Kiah Narayan

Monalisa Hu

EDITOR IN CHEIF

Emma Wang

U M B E R 1 2 visual

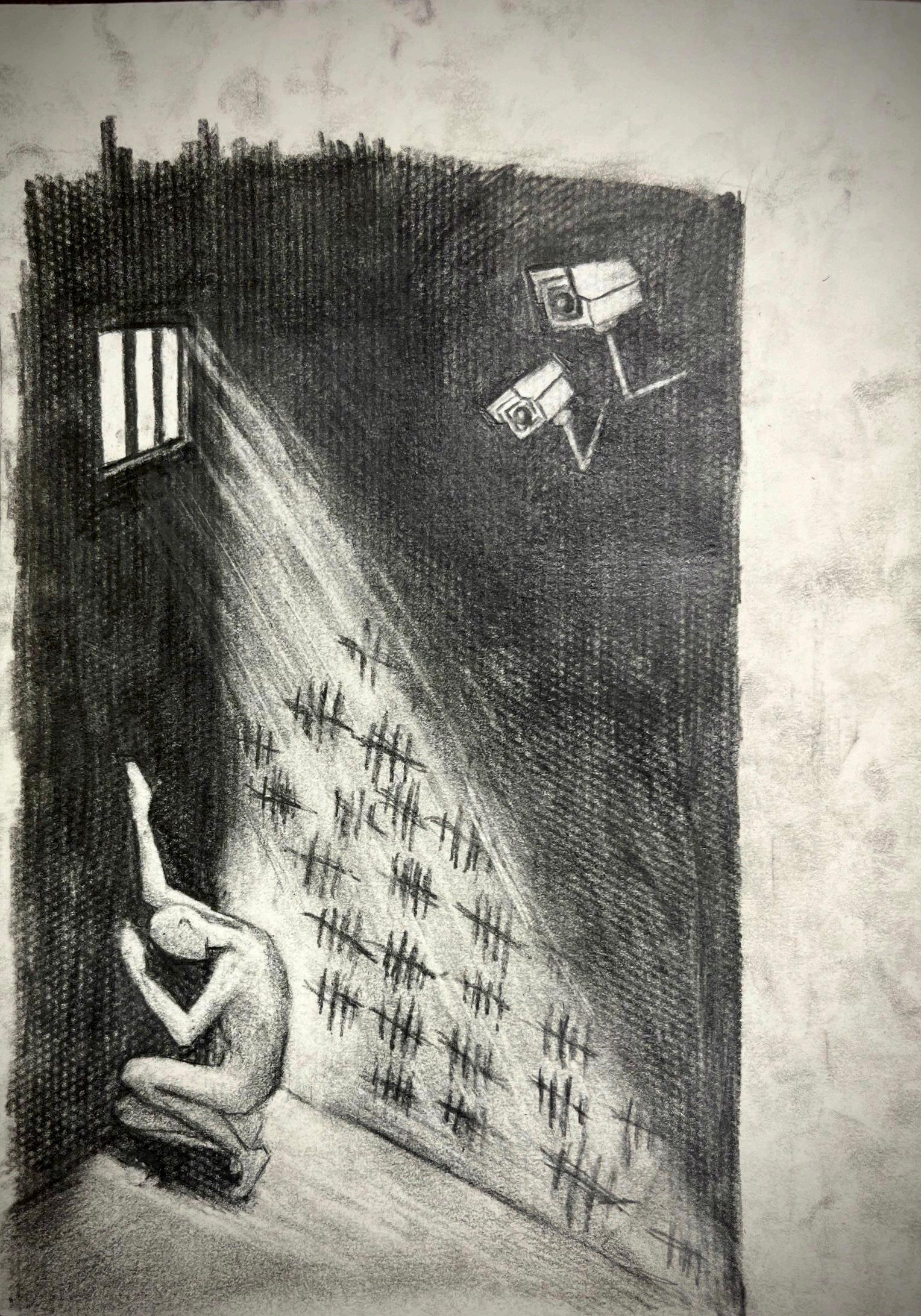

Number 12. You can always choose who you are if you are good. You can invent a new you by thinking of the sour milk stains on your bright orange skin or feeling the dried teardrops in the taste of stale air. See, this is how it's done: you let these sensations seep and mold you into: Is it working yet, Number 12? Have you become a better self yet? Remember, redeem and rebrand. Redeem and rebrand, so you can become someone else when you peel off that orange skin. That’s what prison is for, anyways

theindifferentnoonbathingour son 'ssleepinghead;yourfreshrufflesanddiscolored lipsradiatethesametendernessinslumber.The thoughtofyoumakesmybodyexpand,even ifIamleftfeelingtheacheofanemptybed----your warmth,yourscent,andtheweightofyoususpended inthedimglowofahollowmoon.MyDaughter.You'veleft yourcroptopsandskinnyjeansagain.Itold younomakeup----seenowhowitrunsdown yourfaceandblursyoureyes? Thisisjusttotellyouthatitrainedagain today,newlybornraindrops,theplumpwombsoflife slippingdownachutelikethetime youliftedyoursoftcheekstogreetthem---astonished andfullofwonder.Imissyou,Mom.Iknowthe nightsrightbefore:howyou letmegetdrunkontoomuchflatbeerjustsoyoucouldtake careofme,bewhatIneeded,andshowmethatwithyou Icouldbesafe.Forthis,Ifallasleepcradled,carrying envelopesthat'llopeninmysleep. Nohopeofmiracles;insteadIprayandstareout thewindowatgrayconcreteroadseveryday. Everythingseemsbetterwhentheyarestill andlifeless----timeissecurefromgrowingand changingandrotting Eachwildhourmightaswell lastforever,exceptthatIamstillwaitinguntil youcomebackfromthatstrangeandbarren land----inthecarelessgloryofJuly.

representation of “Number 12” by Maggie Yong

Within These Stained Walls

1) Prison, one of the days when the sun along the bars crossing over the window

I have been made well aware of the fact that the longer I sit concentrating, meditating, isolated within the walls of my mind, the more torrential the buzzing voices become.

Sometimes I am convinced that the walls have a pulse. When my vision begins to blur and the buzzing and ringing fills my ears, when the isolation is too great of a force – the chamber pulls in and rushes out, contracts and relaxes, caves in but catches itself before it falls out once more. When the walls seem to be caving in, the temperatures rise. The soft pulse in my neck rises to the back of my head and behind my eyes. It travels down to my abdomen, my wrists, my fingertips, my ankles. But the retreat of the walls is cool, fresh, as the weight upon my chest rolls down my arms and legs and the ceiling fades to reveal the bright, liberating blue sky. There are no white clouds to interrupt the view. In a Red hot air balloon I rise above my cell, my cage, the suffocating air, the dank and grey corridor and the screeches of metal on metal.

But I know Red was the colour of the bucket grandma and I used to wash ourselves and the colour of the thin rough chord that she once used to tie her hair back when her ribbon had been torn. It was the colour of the sash my love had worn, the colour of love and endurance. Red was the colour of my brother’s blood that I tried to scrub from my hands, my face, my hair, my eyes, and red was the colour of my palms rubbed raw, the colour of the blood that trickled from the dry, white cracks of my skin.

The balloon slips under me, slippery as hands running along ice, and gravity thrusts me once more onto the concrete floor adorned with cracks like spiderwebs. The walls press in, my lungs emptying as I wait to be released once more.

SophieWang

2) Courtroom, May 12th

He sits as if he is melting ever so slowly. With each speech that passes and each verdict placed upon him, his shoulders curl into his body, his head droops, and his legs curl under his chair, twisted, tangled and defeated. Sometimes his left arm will reach towards his eyes to wipe the silent tears and occasionally his hands will come together and cup his face as he seems to choke back tears. As he was escorted in, his eyes had found mine, red-rimmed and glazed over with defeat. His hands, the ones with the ashy skin folded neatly in his lap but he repeatedly picked at the cracks around his nails especially as the prosecution stood to give their opening statement.

“Heartbreak” was never the right word created to describe losing a child because in reality it is the feeling of being wrapped and trapped in a sack, utterly immobilised and only able to observe the inevitable suffocation and final exhale. The pressure can’t be escaped so the natural approach is to welcome it, wallow in it, be pulled under and instead learn to normalise the steady, cold pain and to carry a cloth in your back pocket to wipe the tears that spring to your eyes unannounced.

Intentional injury. Life imprisonment. The words blurred together and the world blurred together.

Before me he falls to his knees as his tears race down his skin and are absorbed by his darkening uniform. His body is a boat caught in a storm of his remorse, guilt, and shame, his narrow and flimsy form being tossed around without direction.

To Forgive and Forget would mean to move on and leave my boy behind. To live without acknowledging his light. This I cannot do. Instead, I can offer my arms and my ironic compassion. I can teach him how to relax into the pressure of the grief, how to take small breaths to avoid the point when all of his breath will leave his chest and the lights will turn out with a sigh. I can lend him a cloth to dry his cheeks and neck.

We hold the brooms and sweep as though it fights the devil away. We launder and dry and scrub and rinse as though it is our hearts we hope to cleanse.

When the sun sets, casting a golden familiar hue on every wall, glowing through the petals of the blossoms, together, we let go of our work. Holding each other we return to the grand house we stay in together. Amongst the eroded concrete walls, under the rusted tin roof, and atop the strong worn dirt, our voices warm up once again as we satiate the craving for connection and savour the hours before dawn.

It is most quiet when the sun rises above the silhouette of the trees with the thick, waxy leaves a while away and the sparrows sing to the village and its tired people. It is dry and still without the noise of the vehicles and the piercing cries of the hungry infants.

She wears a simple thin dress with the rich red sash wrapped around her waist and knotted into a bow in the back. The thick strip of fabric has been fading from excessive wash and exposure to the harsh, cutting strength of the sun overhead in the dried up fields and amongst the constant hum of fruit flies. In spite of its wear and tear it remains a beacon of colour, warmly brightening the cold morning fog and making the daytime heat a little less suffocating. It rustles amongst the folds of her dress as she makes her way to the stream and whips amongst the draughts of wind when the sky becomes overcast and gloomy.

Serendipity brought us together and serendipity held us together. When I worked with her the hours melted into one another, the sun seemed to glide across the sky so rapidly I hardly noticed. At night, time stretched out as the moon seemed to take its sweet time on its stroll across the sky. Hours of thoughtless gazing into the sky passed like the flow of luxurious, thick paint, my heart contented with counting the stars and the seconds until the rise of the sun.

Rain patters on the dirt path that is so overused and hot that the first droplets of rain jerk away with a cat-like hiss and the ones that follow ricochet off the surface before collecting in the cracks made when the sun gets too hot and the soil angrily pulls apart. The setting of the sun cools the wetness and the earth, buds of life spring up from their hiding places – clean, content and beautiful.

In the Wake of a

Breathe in,

As your life fills with color.

For the first time, you are not enclosed in; a four-by-four room tiled with cement Spider cracks along the walls, With hopes and dreams strung up like ornaments Upon the bars of your window.

Breathe out, You are not a poltergeist, Constantly, haunting your life with monotony and dread. You are not some Schrödinger’s ghost to be decided for existence.

You are alive. You. Are. Alive.

Your mind is buzzing Thoughts, viscous with uncleaned molasses and built-up tar

Your face is a stranger in the mirror; like, an ancient polaroid flipping through recolored photos. Awake, from that hazy greyscale dream.

Breathe in,

A crawling sensation of Jamais vu lingers, as The world has rewrote itself in your absence: Treetops reshaped their silhouettes

Leaves dyed in new colors, Sidewalks paved by unfamiliar turns.

Monochrome Dream

New desire paths, carving themselves into the freshly milled landscape. Old nests have made way for budding branches. across the neon streetlights, a stray cat, Trekking through the dandelions; at ease with its destiny.

Breathe out,

Breathe in,

Your pulse sings, Frantically beating, to the rhythm of a hummingbird’s wings, or the sounds of rapid raindrops hitting the asphalt. This vast world, shattering your heart into a magnified kaleidoscope; Occupying you like visions in technicolor, Yet, viscerally real just as the clothes on your back not orange for once.

Feel profoundly terrified because times have irreversibly changed despite you; But be achingly enamoured, regardless, as the world pauses for you to catch up.

See the sunset,

The universe; painted upon the horizon and Elpis dots the sky with shooting stars. A crow in a birdcage, now free to fly You erupt into flames of gold Breathe out.

The Bridge

EmmaWang

I quit smoking ages ago. Still, when Jenny handed me a cigarette from the folds of her wool coat, her fingers brushing against mine briefly, I couldn’t help but take it. She watched me pace the empty bridge, silent, her breath curling like smoke in the sharp winter air. The orange ember flared— a speck of fragile light glitching against the stark, cold smell of her hometown. It was the color of ripe figs, of that hot summertime, of the last time I saw Jenny.

Just a few months after we were let out of prison she took me to a place she called hers. “Put your things here,” she points to the middle of a crowded living room filled with Italian novels and old furniture. “Tomorrow night we go firefly catching.” she says as she empties a mason jar she had used as a cocktail shaker. In the two weeks I stayed with her, I see for the first and last time the blitheness in her smile. I watch her profile in fragments— scrambling eggs for breakfast, always brewing two shots of espresso instead of one, scribbling things into a spiral journal before sunset. Then at night, from the other side of a thin wall that failed to detach the noise, the sound of a piano hollow and star-pure drifting from her fingertips. It felt like a glimpse of something private, untouched by the world we’d come from. I’d lie there in the dark, feeling like I was trespassing, like I had stumbled into a version of her that wasn't meant for me.

That night, when the cold moon slipped through like fractures of iridescent wings I pressed my palms into the wound, trying to stop the bleeding. There were no bandages, no sterilization. Time crawled. Bare back glued to the metal of the bed, the only motion in me were my eyes locked in the etching distance of the light overhead.

I had lost the photo. There was no more evidence of a brief, sunlit moment before the wild flickering of fluorescent lights. And so I realized, the body had always been a second prison. How had I wanted to stay invisible when it held everything I disgusted? The way my muscles tensed in another being’s air; the way my chin steered into obedience, and these limbs bend and fold softly to wash over like running water the cut edges of a fist. This prison held me captive since long ago, sometime in moment between that sticky, slow afternoon of a mother daughter, and the constant, unraveling silence in years after that led me here.

In a sudden shuffle Jenny appeared before me. This was before I knew her at all: she just stood there looming over me, and, silently, dug her teeth into her shoulders, blood trickling down. She didn't tend to my wound. I didn't ask her to. Later, she lies beside me tenderly, her body the tip of a feather falling in the moment it touches the ground. She is resting, her face lifted to the ceiling, eyes closed. Her fingertip brushed the ridge of my scar, cold and tentative.

“Does it still hurt?” she asked. A single tear slid down her cheek. Alarmed, I turned to face her. “Why are you crying?”

On the bridge, I pull away my coat and tugged my sweater aside lightly to reveal my bare upper arm. Numb to the coldness, revealed was a scar at the tip of my left shoulder that I lifted up next to my ear. It was the same one that took me back to twelve years ago, that dull evening I sat still in my cell, holding in my hands a photo of my mother and I. I was incongruously small— lifting my arms upwards to hug the thick trunks of the softest green tree, my mother cupping me with her arms, triumph glowing in the crease of her eyes. In faded print you could still see: sunlight dribbling over a path curving with age slanted in new spring, lushes of fallen debris breathing with the wind. Two identical smiles.

My back scraped the cinderblock. It came in waves before I realized— the metallic clatter ringing out like a gunshot. The thud of bodies hitting the floor. Around me, the riot started to move like a living thing. A copper tang rose in my throat as the air thickened, soured, like sweat and old bleach in a flash of faces contorted with rage. Women fought like animals: their nails digging into skin, teeth bared.

My instinct told me what it always told me, year after year since I was born: Stay small. Stay invisible. But just like how my body had never learned the difference between love and violence, rage built the cruelest walls that disregarded the difference between holding us in and caving on us. The heat of someone’s body jostled past me, the crack of bone against bone as a fist met a shoulder that I had realized was mine. The sensation wasn’t sharp—it was dull, thick, like the pain had been lying in wait, hibernating. It cut too deeply, exposing a crescent of raw, bulging skin.

Astonished, I blinked in recognition and before I even realized, my palm slid atop hers, the weight of her hand as light as water. In that fraction of a second, with her tear stained porcelain skin and empty gaze in the dark, she looked shockingly familiar, soft as every word her lips loosened to the dark. And I knew then that we’d never have to tell each other it was going to be fine. We just lay side by side crying, for in that rigid night it almost didn’t matter if we were sad over different reasons— her because she was chasing her past and me because I was escaping it — we were together in the dark, the mattress damp from our soft warm tears. Slowly, catching the moonlight, the scar had become a narrow thread of silver.

The grooves of our face grew familiar. I told her of the ghetto in downtown Chicago I grew up in, my mother’s dim apartment with the inflatable mattress and the refrigerator’s rumble in low shakes. “My home town is so small,” I say, “there was nothing to do other than get high or get drunk.” She looked at me, her eyes big and brown and earnest, sincerity like a promise opened in space.

Jenny doesn’t ask questions: none about how I ended up here, about the scar that traversed the arc of my jaws or the stagnant absence of my missing front tooth. Yet she makes remembering easy. When I held her hand like clear flesh, I am able to remember things I never remember. Her palm unspools what I’ve buried, they become soft and unbearable and swift as the gentle nod of her head.

I tell her about the science fair— how the gymnasium fluorescents bleached mothers into a single bright swarm. How three hours later, gravel bit my knees in the parking lot’s last island of light. When the security guard shook me awake—his polyester sleeve rasping my cheek— the wet on my collar was melted frost and the salt of my own small animal panting. I tell her men always came and went like they were passing through my mother’s life on their way to something better. I imagine her wishing for warmth in that soft glowing belly half exposed, wishing for flowers to bloom in the pain of the aftermath. The time she skipped my graduation because the new bartender at O’Malley’s poured double for free, and she told herself she’d make it next time—there’s always a next time until there wasn’t. Until seventeen. Key jammed in the lock. His Timberlands dented the table, a kind of guy who thought yelling made him a man. He slurred his words, drunk sour breaths: “Get the hell out of my house”. There was only one other person who saw the walls flinch—my mother standing in the corner, her arms wrapped around herself like she could fold into her own shadow. She didn’t say anything. She just stood there, frozen, her eyes flickering between us. “It wasn’t supposed to be this way,” she cups her hand to her mouth and cries silently. And then, as I reached for the doorknob, slipped $100 into my hand and whispered, “I’m sorry, baby.”

That night, cicadas thrummed the dark. Porch light haloed a dead June bug. I stood scared, dreaming of killing my mother but also dreaming of holding her close. I imagine the nights where it has been dark for hours and she can’t bring herself up to turn on the big light, and all I wanted to tell her was to come home, into the softness and this yellow glow I have kept on for her. To tell her to come home and wrap herself up with me in a tiny blanket where I can hold her against the cold and idle world; stay until my breath fogged the bulb.

The years ticked upwards.

When asked about the house I grew up in, smoke comes out my mouth instead of sentences. Ceiling shadows persist, no longer how hard I try to keep time or erase it. Vodka burns my throat clean, so I let it pool in my ribs, this liquid amber, let it lacquer the shards: mother’s knuckles brushing my spine, my fingernails clawing the couch stuffing, the hiss of the radiator singing alone, alone, alone.

Every now and then when my eyes open to meet the freshness of another broken morning, the sun a thin blade, I hear myself in a distant orbital, we can survive memory but not the body. And then, as always, the past splashes across the night like a siren, and I see myself again— bowing my head over the sink. Swollen eyes, cracked lips. Being met with disgust as I looked up. The touch of coarse cloth and dirty nails clinging to my young body no matter how much I washed it. Vodka never made me forget. How we mirror even in rupture—her face floats in every shot glass, my throat burning as I swallow the moon whole. The child in my marrow kept floating—a pale thing, salt-eyed, still reaching for shore.

never required thinking; her emptiness towards everything, the way she looked at me with her eyes a vessel for whatever the world had to offer cut a slip inside me, and I let my former life leak out into the light, spill into the skin of her soft cleanliness.

And then there was me— weathering itself for ruin. I held in my body the mutilated flesh on the road naked and dead, the memory of being cleaved open like a fruit, the times I let liquor take over and decide whether or not to drive my car into the river. “I swore to never become my mother but somehow I still grew up to let men do horrible things to me.”

“My mother,” she says slowly, “Hasn’t visited me since I’ve been here. I don’t think she can ever accept the fact that I am.”

She smiles; she laughs; she looks at me. She tells me about the beautiful church in the town she grew up in and the line of magenta peonies across her lawn. How every late spring she and her sisters would slide into thin green sundresses, the ruffles of the hem billowing by her ankles as she ran. How remembering wasn’t hard at all; it was those memories of her childhood, her old piano and green dress that kept her alive. Every time something reminded her of music, she would hum a small melody for me that she used to play. I listen, but somewhere hidden in between the beats are where I’d smuggled whole oceans, starlight she’d swallowed to keep her eyes bright.I asked her if she believed in fate. If she saw some gaps as infinite, like time, like the pupils in an eye— how we lie to ourselves that the universe infinitely expands, so that we are all floating and desolate particles in space, bound together by nostalgia for a somehow better tomorrow. And still, she daydreams to who she was before Woodlands Prison and I daydream to who I was before her.

“Tell me more.” She asks more than she speaks. It was a weirdly quiet presence, even the way she inhaled air was restful. The room filled and refilled with our voices. A familiar story from her followed.

So I told her: The car humming beneath the radio’s croon. The cherry wine pooling hot behind my eyes. How the vehicle collided with another, and then the frozen earth. How in the passing headlights through the blurred rain I saw my mother a small dead doe on the side of the road. And for some strange reason I believed it was her. For some strange reason I let that thought invade my senses: a fuse of lavender lotion and the nicotine every time she pressed my cheek to her chest to hold me close. This isn’t the disfigured smell of soil and blood and cement. This isn’t foreign. This isn’t the purr of the engine, the rain splattering violently, my head throbbing and yielding skin soaked to the bone. The crash pulls my body into suspension; my drunkenness is gone all at once and now it is just my empty hands reaching for nothing in the dark, tempting something— someone, to return and cradle me.

Except it wasn’t a doe, but a woman. A mother of someone else.

And my hands weren’t empty, they weighed a raw, lifeless body.

In prison, everyday the sun dips into a quiet wound and dusk floats through a muted curtain of mundane. Our lilted breaths fold in the grinning shadow. The truth was that talking to Jenny

“Was it an accident?” Jenny asked. I didn’t answer. How could I explain that the doe’s eyes I saw held the same shattered light as my mother’s? That the woman’s body felt like a confession?

“I hit a dog once,” she said later. “Swerved to avoid it. Still dream it’s a child.”

The blank walls that used to close in on me, fractured and incoherent, smoothed out as my mouth moved along sentences into an old movie made by my past and animated by our words.

Once the gashed from the riot hardened, a plumped up oval of a thing grew. Over time, it shrank, smoothing into a scar that pressed itself into the folds of my clothes.

At the 3 p.m. count, when the guards’ boots synced with my pulse, I’d gnaw at the ridge. Somehow, through the years after I left Jenny, this became a ritual— my jaw finding rhythm where my voice couldn’t.

Same as the nights I crouched behind the diner, chewing cold fries in the stench of rot. The manager’s shouts sliced —You reek like the dumpster, you hear me?—and I’d clamp down harder, tongue mapping the scar’s braille: Still here. Still here. Same as the day I stood in my mother’s kitchen, eight years gone, the air thick as I dodged the chair she hurled at me. My jaw locked into the scar’s familiarity— an anchor against the tide of her fists, her guttural voice, her why-did-you-come-back. Every bite pulled me inward, back to the ground of my body, the one thing I owned. It became a warm and grounding sense of teeth, of pressure, of pain I could control between me and myself.

If Jenny still remembered this, she showed no signs of it. Her eyebrows lifted slightly, just enough for me to catch.

"It doesn't feel like anything, does it? After all these years."

So she did remember. And oh, how I wanted to lean over and hold her.

I wanted to hold however much of me still lived in her. The nights we held palmful of casual past tenses. The truths I used to curdle in my throat evaporating in the January mist and her flowering glow of a pupil; a simile of renewal. The jars of fireflies that summer, the glass ones that we’d pretend could hold a whole universe inside— tiny lanterns under the red sky promising to lead us somewhere safe. The first time I spoke to her, how it felt like a moth lifting a wing under my ribs. How every once in a while, the light passes through her profile in a way that makes everything momentary seem eternal, and I imagine that she would bring me with her; Jenny, her self-containment, her solitude, her indifference, the way she holds loneliness parallel to existence. This much was in my eyes and passed between us. Please remember me time and time again.

"No, it doesn't feel like anything."

“It’s strange what scars stay with us.” She leaned against the railing, her face illuminated by the soft glow of a streetlamp.

We listen to the whizzing of cars strutting by and Jenny's soft humming between smoke rings. It's getting dark, and I wanted to ask Jenny where she is now. I let my eyes squint against the wind and feel the coldness creep in from the sleeves of my scarf, and I

wonder if she's opened a cafe or gotten a cat. We were getting closer to the end of the bridge, but I still couldn't speak. I wanted to ask Jenny where she is now.

"I wish I could look past everything, like you."

She smiled, amused. "I never look past, or at, anything."

And so I take another drag of my cigarette and look at the hair falling in front of her eyes, letting her remind me of the goodness in this world. Trying to remember the November hills she’s led me to, when the world’s strange weight bowed at my feet and felt more than dust.

The cigarette finishes. It is cold again. The city darkens before us in solid, sharp breaths. Beneath us, a soft chaos of cars and people made a warm stream of blinding lights. It is a silent movie: one glory of a scene that I was able to hold onto a little while longer since I stood on her right side as she made the left turn off the bridge.

She took a last drag and turned to face me. "Isn't your hotel on the right turn?"

"Oh, yeah." I replied sheepishly, and she let out a cackling laugh. She crushed the cigarette under her boot. As she walked away, I managed to memorize the way her shoulders curved. I turned right. She didn’t look back. My eyes are still wary.

prison is an ugly word that you take for granted it rolls off your tongue at dinner tables while i choke up as it passes through my lips

officer, maybe you should think of how time stretches and halts sitting at metal tables under metal coloured lights

Officer,

time is listless here, time is lethargic time slithers like a wounded serpent dragging its heavy coils across the floor and flows like molasses only twice as bitter

what about my family will they drown in the weight of my iniquity as months pass will they roost their heads above the clouds, too far to see and too distant for me to reach?

will i reach for my daughter’s hand in a crowded street only to grasp air and see her face, looming above mine?

i think that my knees will creak when i uncoil them in five years time like rough and rusted hinges that i will have to force straight

will i fumble with the keys of a computer, or plead for a job with weary eyes and calloused hands will i wrap my arms around my brother and hold on too tight will my infidelity seep through to his bones too? will i know how to walk without a cane, without a keeper a step behind?

officer, how does it feel to walk out of iron gates every night and every morning without wearing a pair of distrustful hands?

anaesthesia

dawn.

through a looking-hole twelve centimetres squared in area and fourteen centimetres in diameter bisected by a rusty rod. a capsule of light deferred. papá, papito, papá, papito! who even is 136915 unit 7 block a of san hernando state penitentiary in the greatest criminal justice system to have ever existed on earth in the greatest nation to have ever existed on earth which believes in the greatest god to have ever existed outside of earth? the prison paper’s a wrinkle of time. the chip shop down the road has become a transformative hub for dynamic systematic innovation to foster collaboration between cutting-edge technology and visionary leaders. five miles from a methhead. who misses me? nobody but papito. it was hot, it was a happy meal in a toyota pickup in the parking lot of the mcdonalds off the third exit of the freeway, papito held my hand, i miss papito. i miss you too.

papito isn’t like reverend james. the presbyterian preacher whose soulless words tear apart my tortured tranquillity faster than the AB tore up bruno last night. oh, God almighty, in all his omnipotence and omnipresence and omniscience and omnibenevolence and omnifuckedupedness, must have delivered the highest benedictions to the serial rapist next door who won’t stop ratting his cell wall with whatever muscles are still left in his half-animate corpse! if jesus christ died for this kind of motherfucker’s salvation in this godforsaken place, we clearly have a need for a genocide of jesuses. god said “let there be light”. then god said, “let there be a failure whose failure is such a failure that my failure to recognize that this failure will be a complete failure upon this failed society i have failed to create is testament to the failure of my failed creation!”

god loves you. exile makes you a more pious servant. screeches down the hall. it’s always screeches. and then howling, hysteria, horrid things. they remind you that you ain’t done a single thing that makes these fifty kilograms of horrid flesh and bone human. forty-three years of haunted existence and who have i ever loved that i haven’t singlehandedly strangled, asphyxiated, bludgeoned, garrotted? my jaws open, but all that has been and will be passed into my oesophagus is bland couscous and shrivelled apples. my vocal cords utter phonemes, but i’m a selfish egomaniac whose impulsive rage ruptured a hundred families yet i can’t even say that one single word. that one word! simple as that, one single word. but no, i can’t because papito used to tell me that i would never ever do anything wrong in this world and that’s the one single damn thing that keeps me going through this shit. i’m sorry, papito. your heart is a divine crystal because you still dare to dream. dreams of what happens when you see my face again.

daybreak. dehydrated dawn of dreary dreaming. death.

WAKE UP. WAKE UP. NO THIS IS NOT REALITY. EVEN IF YOUR BONES ARE A PIERCING ACHE OF A CENTURY OF HUMILIATING SERVITUDE YOU WOULD NOT SUBMIT TO YOUR DEATH BY A THOUSAND CUTS. hope keep hoping

even if that word is redemption. even if that word is sin