11 minute read

10. A little change is not enough

10. itt e chan e is not enou h

Realise - certainly if you are working from an existing business model - that a little change is not enough. You are dealing with a transition. According to Professor Jan Rotmans, a transition involves a fundamental change in the structure, culture and methodology of a system: • Structure: institutional, economic and physical infrastructure of a system; • Culture: shared views, values and paradigms; • Practices: daily routines, rules and behaviour.

Certainly in the case of existing business models, conscious entrepreneurship involves a transition in thinking and acting that takes several years. Such a transition requires insight into the history and future of an organisation and a conversion into an appropriate transition approach. The following levers can be used: direction, reputation, relationship, routines and exchange. Below, these levers are discussed in more detail on the basis of the metaphor “Break through the wall of transition”.

At the start, you would do well to ask yourself whether the issues facing the organisation require a change or transition approach. In this respect, we distinguish between fiscal year change management, change management and transition management. Many financially-oriented organisations expect a change to have a return on investment within one financial year. We view this as fiscal year change management, and there is nothing wrong with that. However, it is important to realise that these are short-cycle changes or improvements that you, as an organisation, intend to earn back within a year or by way of depreciation.

If the change relates to a prolonged period and requires a more integral approach, then we need to adopt a change management approach. In his inaugural lecture entitled “Societal Innovation: between dream and reality lies complexity” (Rotmans, 2005), Rotmans sets out the difference between current policy and transition policy as seen from a government's perspective. The table below shows the distinction between change management and transition management.

Transi on i pact

1 3 years 1 5 years 5 10 years 10 years

Current policy

Short time horizon: 5-10 years Facet approach: limited number of actors, one scale level, one domain. Aimed at system optimisation Common forms of control

Transition policy

Long time horizon (25-30 years) Integrated system approach: multi-actor, multi-level, multi-domain. Aimed at sustainable system innovations Mix of old and new forms of control

Complexity and uncertainty as a problem

Complexity and uncertainty as a starting point Regular policy arenas Transition arenas Linear knowledge development and dissemination Learning-by-doing, doing-by-learning and learningby-learning

Many organisations take too little time for the actual transitions, or as otmans puts it: “Profound transition requires at least five to ten years, and in my experience, more likely ten than five years”. As a result, many organisations get stuck in operational matters due to pressure of profitability and production discussions rather than managing the transition that is, by definition, ongoing. It is often said, therefore, that many transitions fail. Our assumption, however, is that they do not necessarily fail, but rather are declared a failure too soon. Actual transitions require more than one financial year to come to fruition. From a transition perspective, we assume three three-year periods: (1) looking for niches and experimenting, (2) absorbing and accelerating and (3) achieving breakthroughs.

The phase of “looking for niches and experimenting”, requires courage to start from the organisation and management. Starting by looking for niches in places within the organisation where changes are already occurring and which fit the desired future image. The trick, according to Ben Tiggelaar, is to work on the basis of learning objectives and not performance objectives, precisely to provide the space to make mistakes and learn from them. Or as he puts it: The quickest way to performance is by taking a learning detour. By regularly reflecting on learning, it becomes increasingly clear which initiatives and actions work and which do not. In this phase, you build towards actions and interventions that work one step at a time.

At some point, the organisation and its employees will have a bundle of actions and interventions at its disposal to absorb and work with, allowing them to produce results in terms of both learning and performance. This is the beginning of the “absorb and accelerate” phase. These actions can be used to accelerate and make the intended effects visible, thus “infecting” more employees who start working in line with the envisaged future.

Subsequently, the bundle of interventions will become so solid that new behaviour and work processes will see the light of day, bringing us into the phase of “achieving breakthroughs”. In this phase, it is important to perpetuate these and to let them become part of the envisaged new structure or as mentioned above, the new regime. This topples the wall of transition, and the vision of the future becomes a reality.

Organisational archaeology

The quote by philosopher and writer George Santayana (1863-19 2) “Who does not know his history is doomed to repeat it” highlights the relevance of organisational archaeology. Without knowledge of the history of the healthcare system, the logic behind the number of hospitals in a country cannot be understood. And the relevance of historical awareness certainly applies to organisations.

Historically established rules Many rules within organisations are historically established, without us realising this today. The statement “This is how we have always done it here” is often already historically charged. To gain insight into the history

of the organisation, creating a timeline can be an insightful exercise. Take a look back in time and describe the key moments in the organisation's history using dates. Consider questions such as: • When was the organisation founded? • Who founded the organisation and what personal characteristics did he/she inject into the organisation? • What good and bad moments has the organisation experienced? • Who has stood at the helm and what impact did they have on the organisation? • And in the context of the B Corp standard: which standards has the organisation worked with and what were the resulting positive and negative experiences?

This historical awareness adds colour to the functioning of the current regime. Or as Loorbach puts it: “a regime concerns the collective ways of thinking, working and organising that have grown historically.” “This makes the word regime often equal to the word structure.” And as many will recognise, structure tends to continue to exist even if it is not necessarily functional with respect to new issues. After all, new issues cannot be tackled with old solutions. This often requires the courage to look and act differently.

If you look closely, however, many organisations have so-called niches. Places and people within the organisation who want to and can work differently. Remarkably, these people do not always get the recognition they deserve, as they are often perceived as difficult. In such cases, there is a significant risk of these people being pushed out of the regime. So how do you deal with people with fresh or unconventional ideas within the organisation? Let's be realistic, though. Too much of a good thing also leads to unwanted effects. However, we urge you to look closely at how you can use the niches, the people with fresh or unconventional ideas in order to keep playing the game that changes by definition. Also consider engaging students and new colleagues who have not yet been contaminated by history.

Game changers We mentioned the relevance of historical awareness and the effect of history on the prevailing regime. To break the prevailing regime, the challenge is to sketch a future that is attractive to those directly involved. This is already a break with the prevailing literature on change management as expressed in “The Fifth Discipline” (Senge, 2006), which claims that urgency is required. Well, for many employees, urgency equals the risk of a fear reflex which - as we know from psychology - leads to three reactions: flee, fight or freeze. In all three cases, this is not the desired action when it comes to the intended changes. It is desirable, therefore, to develop a sensory description of the future. A future that inspires and invites employees to “go on a journey”. The insights gained from history and the description of a desired future create understanding of the transition path for the organisation and the actions required become clear.

Mapping the rules of the game

Transition management recommends categorising this "from - to action" into three areas: structure, culture and methodology. In other words: map the rules of the game.

Structure Structure involves both the structure of the market the organisation operates in and the structure that is required of the organisation to be future proof. Let’s not forget that structure is also determined by applicable laws and regulations, which are subject to change.

Methodology The methodology relates to typical actions and routines of the system, or literally "This is how we work here!". Long-established working methods are difficult to break out of. They are literally and figuratively changing practices, for example as a result of ongoing digitisation. In practice, we still regularly see a paper reality,

varying from manually entering receipts to sending pay slips on paper. These practices can be influenced by innovation and experimentation, so that people experience that things can be done differently.

Culture Since effective change is actually brought about by different and often new behaviour, culture is a building block that should not be underestimated. It’s not surprising that Peter Drucker is often quoted with “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. Hofstede's culture typology helps to gain a quick understanding of both the prevailing and desired culture through five dimensions: (1) small versus large power distance, (2) individual versus collective, (3) masculine versus feminine, (4) low uncertainty avoidance versus high uncertainty avoidance and (5) short-term orientation versus long-term orientation. For the accountancy sector this transition looks as follows.

Elements

Structure

Culture

Methodology From

Focus on procedures Hierarchical organisation Data as bycatch Focus on the relationship, with the procedure as the foundation Network organisation Data as a starting point

Short term Masculine Individual Procedure-oriented Accountant Strategy and process-oriented Data interpreter who is also an accountant

By having a clear picture of the history, the desired future and the current and desired rules of the system you have laid the basis for setting up and managing the transition.

Setting up and managing the transition

Working on impact business models requires mobility from organisations. Mobility that is needed to accelerate the intended transition towards the desired future. This is not a question of malleability, but rather of helping to bring about the intended transformation and to manage it. Transition management assumes that a necessary movement will always occur and that you can in fact only accelerate it in the desired direction.

To

Long term Feminine and masculine Collective

Five levers To control the mobility of organisations, we distinguish five levers: direction, reputation, relationship, routines and result, which we will explain one by one below. An analogy with the so-called “five-slice pie chart” is appropriate here. Managing a transition requires elements from each part of the “five-slice pie chart” (the levers), so that the transition can continue. Using the Transition Profile below, you can bring into focus the current and desired situation of your transition to an impact business model in a practical manner. For example, use an X for the image of the current situation on a scale of 0 to 5 and a 0 for the desired situation.

5

0

Determining the direction Determining the direction has two points of action, namely determining the direction and implementing the direction, also referred to as strategy realisation. Determining the direction involves having an insight into the developments in the market and society, formulating a vision and mission and converting these into strategic themes that are relevant for the organisation.

Establishing a reputation Establishing a reputation can give the impression that it primarily concerns the outside of the organisation and is based on slick marketing campaigns, and that is exactly not what we mean. Here too, there are two sides to the coin. Reputation is one side of the coin, with the other side being the organisation's identity. Or as the saying goes: "Starting on the inside is winning on the outside".

Developing relationships Research into the so-called service profit chain shows that organisations are well advised to put the relationships with employees first, based on the idea that ultimately it is the employees who maintain the contacts with the customer. So doing good for the employee, by definition, means doing good for the customer, according to research by the renowned research agency Gallup and by Aukje Nauta.

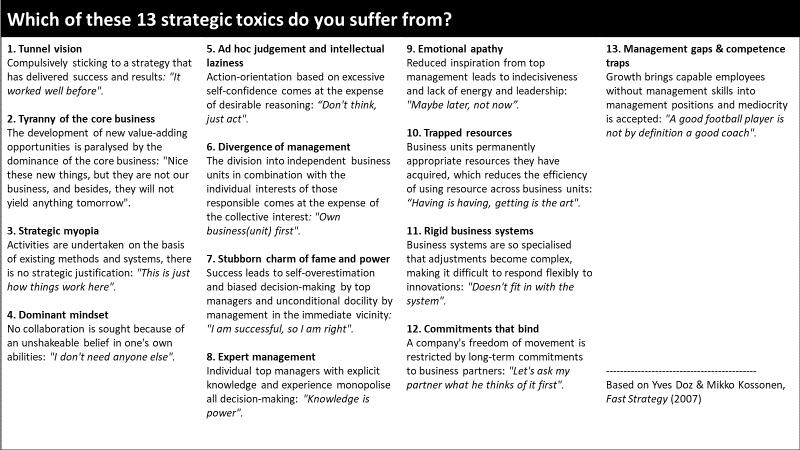

Identifying routines The routines lever also has two perspectives: processes and patterns. Processes are about the actual work processes and the way they are executed within the organisation. It is precisely through the functioning of these processes that it becomes visible whether an intended development or strategic direction is embedded at the level of day-to-day work. Patterns are about ingrained ways of thinking and acting that can impede the realisation of new activities. In the book Fast Strategy (Doz & Kosonen, 2007) these are called "strategic toxics".

Achieving results The fifth and final lever that applies to transitions is the achievement of results and the method of management and accountability that plays a role in this. Here too, there are two perspectives, namely “focus on indicators” versus complementing “intended effects”. In many organisations, the main focus is on financial indicators; a major step forward would be a more integral focus, for example based on the Business Balanced Scorecard (BSC) as developed by Kaplan and Norton. In view of developments such as the Sustainable Development Goals and frameworks such as the B Corp standard and the Global Reporting Initiative, there is another dimension to the lever of achieving results, namely that organisations are increasingly expected to be transparent about the actual impact they have in ecological, social, societal and economic terms.