Calling An Unexpected

Lyndon Spiller

Lieutenant Colonel Lyndon Spiller, 2006.

Lyndon

life took an extraordinary turn when he received a calling at eleven years of age. Forced to overcome hurdles, he developed analytical and practical skills to help achieve

goals. He fulfilled his calling with humanity and connected with people at many levels around the

Lyndon frequently injected his quirky sense of humour into our interviews. Lyndon’s wife, Julie, helps as his memory-keeper. She gently prompted him as needed and even provided a partial draft. This story is a heavily edited and rearranged compilation of the interviews and draft.

Julie worked alongside Lyndon throughout his life. This inspiring story belongs to her too.

Written by Jennifer McNeice

Many thanks to Julie Spiller for her organised notes, timeline, partial draft and ability to quickly find photographs. Her important contribution to this project is greatly appreciated.

FRONT COVER: Lyndon in Papua New Guinea, 1967.

Growing

Gathering speed, I swept down the street and turned into Stonehaven Avenue where I met a car parked on the wrong side of the road. Exhilaration ended abruptly as I slammed into the car and found myself on its roof.

Three days earlier, my parents had given me a restored second-hand bike for my tenth birthday. Now the front wheel of my new bike was buckled and I couldn’t straighten it. Dad found me sitting on the side of the road looking very dejected.

Money was tight at home and I had to wait three months to get the bike repaired. I tried to pay for it from my pocket money but I didn’t have enough. Later, I learnt to make my own repairs and keep the bike in working order. I was developing skills that would help to fulfil my unexpected calling.

Our home in Stonehaven Avenue, Malvern.

Another Bicycle, 1960.

My father

My father, William (Bill) Clarence Spiller, was a fitter and turner who made compass cases during the war years. Later, he worked as a storeman.

His father travelled from England to Australia via Canada, Hawaii and New Zealand. He arrived in 1908 when he was 23 years of age.

His mother’s family came from England in 1844 and Ireland in 1850 to Colac, Victoria.

Dad cutting 90th birthday cake, 2008.

My parents, William & Nada Spiller, 1944.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected

My Mother

My mother was Nada Veronica Tasker Burr. Her family came from England to Australia when she was eight years of age. Nada was a legal secretary before working at the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind. She gave up secretarial work when electric typewriters and computers started to take over. Nada continued using her manual typewriter to write letters to the family. She was always particular about her work and was a perfectionist in all she did.

Both of my parents played violin and Nada was often asked to play solos. In later life she took up the cello. She enjoyed the challenge of mastering the different techniques and was soon in demand at various concerts.

With Grandma Burr at Lake Rowan, 1952.

Nada at her typewriter.

Nada and her violin.

Grandad and Grandma Burr, 1960.

6 Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Early Family Life

Australia’s participation in the Second World War ended a few months after I was born. We lived in East Malvern and I enjoyed the freedom to play with other children in the street. My older brother Geoff and I did not always get along but our differences disappeared if one of us came under attack from outsiders. We became close in later years.

I often rode my bike around the suburbs, just for the sake of riding. I joined the local racing team’s training at the bike track. But races were held on Sundays, so I knew I would never be allowed to participate.

One day, I rode to Geelong with my friend Terry. Getting there was okay, but Terry was not used to long distances. He struggled home while I steadied his seat and pushed him some of the way.

Lyndon & Geoff, 1949.

Lyndon and Geoff, 1947.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling 7

Early Family Life

My parents were members of the Salvation Army church and for many years Dad was the deputy bandmaster. When we were old enough, Geoff and I both learned to play an instrument and joined the band. Later, Geoff was the principal trumpet in the Queensland Symphony Orchestra for many years.

In 1957, I was a member of the Malvern male voice quartet. The quartet became quite popular, performing at Salvation Army concerts, church services and other gatherings.

A cassette recording circa 1965 of the quartet was circulated to members of the Malvern Corps. A short time later, the members moved to other places and the quartet was disbanded.

Julie: In 1983, the four were back in Melbourne at the same time. They decided to give a reunion concert. It was also recorded and copies are still bringing blessings to those who remember the group.

School did not interest me until I was able to study technical drawing. My marks improved then, when I found my favourite subject.

I got detention on my last day of school. I turned up, but when the teacher turned his back, I threw my bag through the open window. The next time the teacher turned away, I went out the window and never came back!

Geoff playing trumpet in younger days.

Geoff playing trumpet, 2008.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Salvation Army bandsmen, Geoff, Dad & Lyndon, 1959.

Lyndon and Geoff, young musicians, 1954.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

A Calling

Around the time of my calling, 1955.

When I was eleven, we stayed with my aunt, uncle and grandparents at Echuca. My uncle was a minister. We went to a couple of services and it was probably a Sunday evening when we saw a film about missionaries in Africa.

I watched this film and thought, ‘This is my calling’. I knew that the Lord wanted me to be a missionary to the people in Africa. It was the Lord saying, ‘These people don’t have ministers. They don’t have directions. They need to listen to what I’m saying.’ And I was to be the translator.

I’m no good at languages at all, but I’m okay with people. When Mum and Dad heard that I wanted to become a missionary they said, ‘It’s not you, is it?’

My parents were not well off. Missionaries were usually doctors or teachers and I wasn’t a good student. I didn’t have to pick up a pen to know I would struggle. I said, ‘No, it’s not, but I want to do something now’. I was eleven. I didn’t doubt myself.

Mum doubted it, but she said, ‘If you say you’re going, we will back you’. My parents knew that I had God’s call to be a missionary and whatever that might hold, I had to pick it up and run with it.

That started everything rolling. I listened to services and thought about how it applied to people. Occasionally, I would sit back and look at it from a distance and say, ‘He doesn’t want that of me, surely’.

Uncle Des Burr and his daughter Marie.

Mechanical Interests

I graduated from scooters to bicycles to cars and enjoyed pulling them apart and putting them back together.

My first car was a Morris 10 Series M. It gave me a good mechanical education because I could not afford to pay for repairs. If any part needed repair, I took it out and fixed it myself.

On an early trip, I realised I was going too fast from Glenferrie Road into Dandenong Road. The brakes would not work. I ran the car into a tree to stop it. I was okay but the car was badly dented.

A lady on the other side of the street stared at me, in frozen shock. I got back in the car and crawled home, which thankfully was not far away. The car was leaking oil, which had got on the brakes.

With my first car.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Mechanical Interests

Julie: When we first went out together, Lyndon’s car was still in pieces so he borrowed his father’s car. When Lyndon pulled over to look at the map, a drunk driver’s car ploughed into him, ripping open the rear mudguard on one side.

The car was still running, so Lyndon continued driving to our place. He was late, but we took off for the city to attend the theatre. A mile down the road Lyndon commented on the rain. There was no rain on my side. We pulled over and found that a hose was split.

We sat there for over an hour waiting for the RACV. Then we returned to my place to find Mum had changed into her dressing gown and put rollers in her hair. Everyone was embarrassed. It was a first date to remember!

On another occasion just after the Morris had been repaired, Lyndon took my cousin and me to the drive-in. The car quickly started to make a terrible noise. We decided to use his brother’s car instead. Geoff had given some instructions for using his car but Lyndon couldn’t remember them – until we left the drive-in and the car stopped. Oh yes, fill the tank, it is nearly out of petrol. (Later, he found the cause of the terrible noise was a loose bolt on the flywheel.)

Mum once commented that I spent more time sitting on the car’s running board watching Lyndon make repairs than I did being driven around.

Morris 10 Series M, 1963.

Apprenticeship & early work

After leaving school, I became an apprentice refrigeration mechanic working for Snellgrove Electricland in Malvern. In the first year of apprenticeship, I won first place in the state among first year refrigeration mechanic apprentices. During my third year of apprenticeship, the business was scaled down to one qualified person.

The apprenticeship commission tried to find another place for me, but the work was always different from my first job in domestic refrigeration. In various placements, they had me stripping motors for shop display units; working in a large industrial refrigeration complex; and wanted me to start again in a different apprenticeship.

I worked on refrigerators like this.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Apprenticeship & early work

After a few months I left my apprenticeship and worked as a storeman for a Venetian blinds manufacturer. When I got my driving licence, I changed jobs and became a driver for Hermes Typewriters.

Between 1965 and 1972, all twenty-year-old Australian men had to register for national service. Potential conscripts were selected by a birthday ballot where numbered wooden marbles, each representing a day of the year, were drawn from a barrel. My birthdate was drawn in the first ballot, but my eyesight failed the army medical test.

1960s livingroom with Venetian blinds.

Hermes typewriter, 1960s.

National service ballot balls.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected

Papua New Guinea

My longtime friend, Doug Palstra, was working in Papua New Guinea and suggested I come to Port Moresby to earn more money. I went just before my twenty-first birthday and quickly landed a two-year contract with the Commonwealth Department of Works. Initially, I managed the stores and ensured that items were logged in. Later, I was responsible for receiving and disbursing ordered items that arrived by ship and plane.

I also helped at the Salvation Army by dropping off and collecting things, and soon became good friends with Albert Loder and Lieutenant Bill Mole. We rode our motorbikes around Moresby, sometimes a little too fast. At weekends, we visited other Salvation Army centres. I made long-lasting friendships and strengthened my own sense of independence.

On Sundays I rode my bike about 3½ kilometres to Boroko, left my bike, took whichever vehicle was available, and drove around picking up kids for Sunday School at Hohola. At the end, I would reverse the process.

I left my heart in Melbourne. Frequent letters, occasional tape recordings and a single phone call were the only communication links to Julie. Once, I put an unopened letter in my top pocket to enjoy at leisure, and lost it. Fortunately, a kind person found the letter and put it back in the post. It turned up eventually.

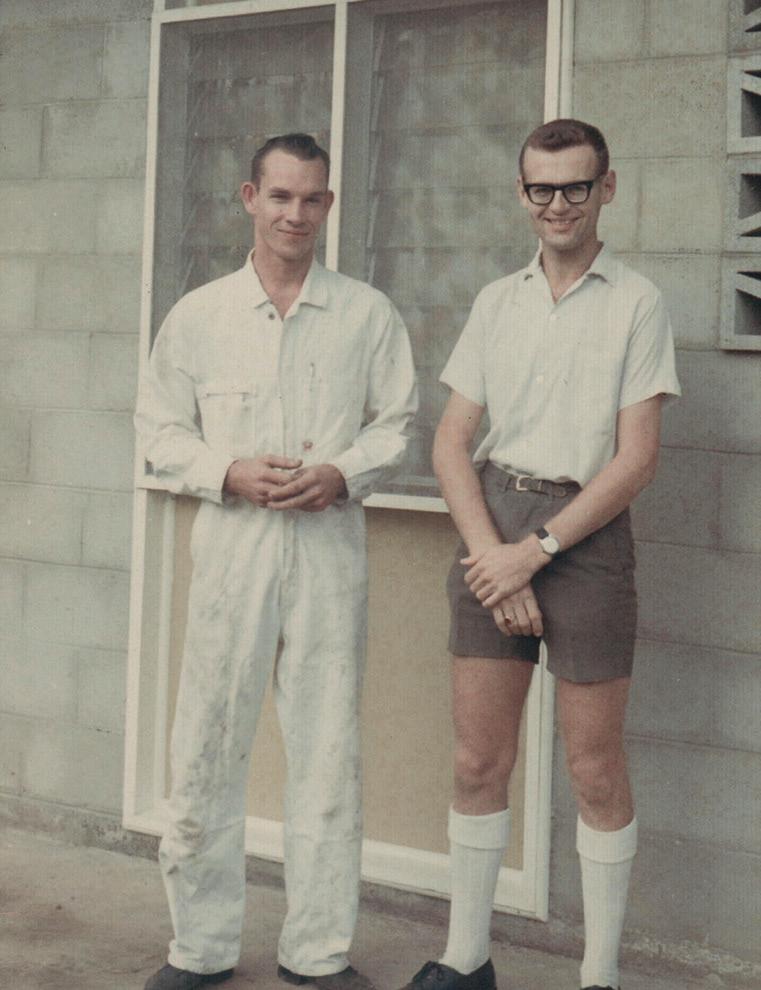

Albert and Lyndon in Papua New Guinea, 1967.

The bike with the side bags, a black BSA, was mine. Bill rode the thin black one, and the red one was Albert’s. We had a lot of fun with those bikes.

16 Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Papua New Guinea

Julie: When Doug was home on furlough, he tried to stir things up by telling me about the nice ladies in Moresby. It didn’t work. Lyndon had already told me about the young lady who often rode pillion on his bike. She was courting a guy back home.

Maureen was the best passenger as she moved with the bike and I hardly knew she was there. I had to make her hold on just so I knew she was still there. People were known to be pulled off the back of bikes.

When I came home from Papua New Guinea, I bought a blue Hillman Imp car and worked as a storeman for SKF Ball Bearings.

With Julie in the Hillman Imp.

Home in donga 27.

With Albert and Bill at home in Boregaina.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Love and Marriage

Julie’s cousin is five days younger than me and we both went to the Malvern Corps. Sometimes Julie went there on Sunday, instead of going to Springvale where she usually worshipped. That’s where I first saw her.

Julie: He used to ride his bike to South Yarra to watch me play basketball. I wasn’t aware of him at that stage. He wasn’t in my consciousness.

She was in my jolly conscious! I probably did that for about two years. We went out in 1963 when she was sixteen and I was eighteen.

Julie: We went out on a double date. After that, when Lyndon came to ask me out properly, his Morris was off the road so a friend drove him. After he got out of the car, he decided not to go in after all. His friend locked the doors and said he would only open the doors after he had been in to ask.

Within a few months of Lyndon’s return to Melbourne in 1967, we announced our engagement. We married on 14 September 1968 and the reception was held at the White Peacock in Hallam.

We moved into a little flat in Caulfield. That was fun. We used to put toast or Salada biscuits and cheese under a little reflective toaster. One time, we forgot they were there and nearly set the flat alight. Another time, while we were telling someone about it, we did it again! We had that flat for three months, then we went to live with my parents.

On our wedding day, 1968.

Our flat in Caulfield, 1968.

With our parents.

Lyndon and Julie.

After the ceremony.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Training for Ministry

Julie: In March 1969 Lyndon and I entered the Salvation Army training college. We had two years of formal training for our years of ministry as Salvation Army officers.

It was a matter of learning as you go. Pick this up. Pick that up. It was mostly head learning. I am not very good at that sort of thing, unless the car is falling apart. I can do the practical thing by picking it up and doing it. Exams were a bit of a struggle. I am not sure if I flunked it, but I did it.

Julie: No, you didn’t flunk.

We studied together and I managed to get through.

Julie: In the first year, the cadets had to prepare a research project. Lyndon chose the History of the Salvation Army in Papua New Guinea as his topic. He won first prize for his efforts.

Julie won second prize.

It was a surprise to me when I won the top prize. Remember, Mum typed it up for me. I did all the research and scribbled it up, then Mum typed it up perfectly. I couldn’t have done that. It also involved Mum and I think she appreciated that.

My research project, 1969.

Training for Ministry

I was selected to be the flag bearer for our session because the original choice took time out. When he returned, I offered to stand back but the principal wouldn’t let me do that. In the end, we both carried the flag at the commissioning. It looked funny and it gave the whole session something to laugh about.

Julie: After two years of training, our ordination and commissioning weekend was held in January 1971. Each year the training session has a name and we were known as ‘The Undaunted’ session. After the ordination and commissioning, we were given our first appointments at a large gathering in the Melbourne Town Hall. We were sent in charge of the corps at Broadford, Victoria.

Lyndon the flagbearer, 1971.

‘The Undaunted’ session, 1970.

Entering Melbourne Town Hall.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Victorian Posts

At Broadford, we sold our Hillman Imp because it was too small for picking up children for Sunday School. We bought a Falcon station wagon.

One day we helped the Searle family bring in the hay bales and came down a hill. Phil was on a motorbike. Julie was in the truck with the Searles and I was on the back of the truck.

Julie: The truck brakes failed and we were hitting bumps as we came down the hill. We eventually turned into a paddock at the bottom where the long grass pulled us up. But Lyndon was not on the back. He had flown off holding on to a hay bale. He landed on the bale and was okay. We got a fright but then we had a good laugh!

After a year at Broadford, we were sent to the Benalla Corps, where we did a lot of work with the young children and pensioners. We would take a carload of young folk with us to Shepparton or Bendigo when there was something on there. Julie trained the timbrel brigade and they were the best in the Division. They were good kids.

We became friends with Don and Jenny from the Methodist church. They were good people and they became our refuge from work.

We also conducted Sunday Services at Seymour for a time. That was about 100 kilometres from Benalla and we went there at least every two weeks.

I still wanted to go to Africa. I was very inspired by the story of Laurie Coleman who was in Africa for a long time, although I didn’t know him personally. We met Eva Burrows who was the Salvation Army General, the world leader, for a while. She had worked in Zimbabwe when she was younger and someone arranged for her to talk to us. I told her I wanted to go to Africa although I didn’t have qualifications.

She said, ‘But I hear you’re a jack-of-all-trades and we need them’.

Station wagon at Broadford, 1971.

Benalla Sunday School, 1973.

Victorian Posts

Julie: That was the reality. Everyone said, ‘You’re not a doctor and you’re not a teacher so you won’t get to go’. But we did.

We thought working with blind people could be an avenue. We started learning braille before we realised that was a bit pointless because it was English braille.

Julie: I had always thought I would go to Bangladesh. It was Pakistan in those days. I asked Lyndon, ‘What would you do if the Army said we don’t have a position in Africa but you could go to,’ I didn’t want to say Pakistan so I said, ‘India’.

He said, ‘I would have to think and pray about it’.

Within a month, we met up with Lyndon’s former corps officer, minister, who knew about his desire and knew that we were learning braille. He said, ‘I’ve had a letter from HQ. They are looking for someone to work with the blind in India’.

Lyndon said, ‘You’ve been talking to my wife’.

And when he got the letter, it said Pakistan. So we went. That was how we got into overseas work.

That was another way the Lord spoke to us.

After nearly two years at Benalla, we were appointed to serve as missionary officers at the Sunrise Blind School in Pakistan. In preparation, we were transferred to Alamein Corps in Melbourne for further study and I grew a beard to avoid shaving rashes in the hot weather.

Julie: The beard didn’t go down well with some of the old ladies in the corps. One complained that they had to look at him every Sunday with THAT beard. However, it stayed and fifty years later it is still there!

One night we came home to find the back fence on fire and the boss hosing it down. I had mowed the large lawn and thought I did well to get rid of the clippings into one place. But they combusted.

My passport photo, 1974.

Sunrise Institue for the Blind, Pakistan

I was the superintendent of the blind school. It was in a Hindu ashram which had been taken over at Partition and we rented it from the government. In our house, the living side was on the left and the bedrooms were on the right. There was a courtyard in the middle and when the monsoon rains came, the only way to go across the house was via the front veranda.

The students studied arithmetic, geography, the national language Urdu, music, handcrafts, physical education and mobility training. The girls also knitted and had cooking classes. Students learnt to make cane chairs, make rope and weave baskets. Some went on to earn their living with the crafts. Our sister organisation was a hostel for the boys with a workshop for producing and selling the goods. We also had a braille room where translators transcribed books and exam papers.

The boys played cricket by sound alone. They used two 44-gallon drums as wickets and beat the drums to communicate. Beating with hands identified the drum’s location; with the ball warned they were about to bowl; and with the bat said they had finished their run. They used a steel ball with a stone inside and were really good at distinguishing the beating of the ball and the bat. In Australian blind cricket, the length of the hit determines the number of runs. These guys actually ran. They didn’t need any sighted people to play or umpire.

Zahoor had a generous sponsor. We were able to buy him a tabla and harmonium and other musical instruments. He became a music teacher when he finished school.

Blind cricket in Pakistan.

Sunrise Institue for the Blind, Pakstan

Sharif was deaf as well as blind. We didn’t usually take children with multiple difficulties but he had a hard time at a Muslim school and walked for days to get to the Christian school. He was a big lad with a gentle disposition. He used to put his arms around me and pick me up and say ‘Sahib Ji’, a greeting of respect.

Julie: Afsal’s father brought him to the school and begged us to help him. Afsal had been in great pain for a long time. He had advanced glaucoma and couldn’t close his eyes because they protruded like the ends of your little finger. They were constantly weeping. He couldn’t bear the light and wore his shawl well down over his face.

Lyndon knew it was not a promising situation but he took Afsal and his father to the eye hospital. He said he would pay the cost of treatment if they would follow the doctors’ instructions. It was hard. The doctors removed Afsal’s eyes.

One day Afsal was on the swing and he called out to me, ‘Memsahib, I can see!’ He had the biggest grin. I think he meant that finally he could think because he had no pain.

We charged a small fee for students if the families could pay, but Afsal’s family could barely live from the small plot of garden they cultivated. One day his father gave us a little bag of barley for helping his son. His gift must have represented a good part of his latest harvest.

We used it to make a barley cordial drink for the whole school. It was a bit like the Bible story of King David pouring out the water that his soldiers had risked their lives to gather from the

Afsal couldn’t close his eyes. Zahoor playing tabla.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling 25

Sunrise Institue for the Blind, Pakstan

well near Bethlehem for David to drink. Afsal grew into a bright and mischievous child with an enormous personality.

Our driver was a terrible person but a brilliant driver. Julie: We learnt that if there were a lot of people milling around on the road ahead, you should turn and go another way. I felt safe with our driver because he never drove anywhere near trouble.

But then he brought a gun onto the compound and was showing it to the blind kids. I told him he had gone too far and asked him to leave. He had also brought some men on to the compound who were subsequently arrested for murder.

One time we went to buy new metal beds because there were white ants. As we were loading them on to the truck the owner brought out a chair for me to sit on. Our driver said, ‘He doesn’t need that. He’s Australian, not American or British. He works!’

After we had been at the school for about eighteen months the government decided to nationalise all handicapped institutions. Superintendents had to leave and were not allowed to return, even for a visit. We were very sad to say goodbye to the children and staff.

Our house at the school.

Opening the school front gates.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Lahore Headquarters, Pakistan

We moved from the school compound to the Salvation Army headquarters compound in the centre of Lahore. The compound had a hostel and we enjoyed our encounters with many travellers.

Julie: Lyndon worked in the finance department at headquarters and eventually took responsibility for looking after all the Salvation Army property. Our cook, Sardar, had come with us from Sunrise and his wife, Martha, became Rhys’ ayah. She looked after him each morning while I also worked in the finance department.

Then I became the territorial youth officer, in charge of children’s and youth activities, education courses and recruiting Salvation Army officer candidates. I did office work marking correspondence course lessons and travelled throughout Pakistan to the various Divisions (diocese).

One of my first tasks was to travel to Karachi, Hyderabad, Jhang, Faisalabad, Shantinagar, Sheikhupura and many more divisions for the annual youth rallies. Children in each division competed in singing, Bible recitation and written Bible knowledge questions.

Cook Sardar Khan, far right; ayah Martha, far left; and their children, 1976.

Our house at Lahore Headquarters, 1977.

Lahore Headquarters, Pakistan

For three weeks of each month, we enjoyed visiting villages to conduct Sunday meetings and meet candidates. We used an Austin Gypsy four-wheel drive from the local Uniting Church diocese. Its engine would suddenly cut out and I spent a long time trying to find the problem, often bringing parts into the lounge room. Eventually I found a piece of straw in the distributor. It moved around and occasionally blocked the fuel flow.

Julie: At one village, the Gypsy became bogged and oxen had to pull it out because Lyndon forgot to reinstall the drive shaft and the car was locked in two-wheel drive. After a year, we returned the Gypsy and hired a car from another missionary.

We travelled to Karachi by train. As expatriates we were able to travel in the first-class carriage, but our assistant translator had to travel in third class. So we booked four sleeper tickets in third class. When we moved from our seats up to the bunks, the other passengers spread out and soon there was a sea of bodies below us. The beds were a very narrow wooden shelf resembling a luggage rack. Julie didn’t sleep much as she held Rhys between her legs to stop him rolling off. We enjoyed the journey and the interactions with our fellow passengers who were quite curious about us.

In the middle of the year, daily temperatures over 40 degrees dropped into the mid-30s at night. As the season changed, rising humidity was followed by dust storms, then the heavy rain of the monsoon. The weather was still hot but the rain could contain ice.

In summer, the mission families spent their annual leave at Murree. It was cooler there, in the hills. Murree Christian School was an interdenominational school run by the various missions and in summer it was the centre for social activities. There were concerts, athletic days for the students, a barter sale and an American-style graduation. It was a close community where families formed enduring friendships.

The Gypsy, 1976.

With Captain David and locals at a village in the Punjab, 1976.

At a Corps Cadet Camp at Jhang, 1977.

Lahore Headquarters, Pakistan

Julie: Boarders moved out of Sandes, the school boarding house, and we stayed in one of the rooms. There was a shower room but rats ran around the hot water systems in the mezzanine above and looked down into the shower. We became adept at heating a bucket of water with a heating iron and splashing it over ourselves with a beaker. We heated water the same way for laundry. Nothing dried in the misty weather. We made a drying tent by hanging sheets over a clothes airer and blowing fan heat into it.

The road up to the house was very steep. Cars often took an unsuccessful run at it and had to slowly back down around the curve to the bottom and try again. Then passengers would alight and push rocks behind the tyres to stop the car rolling back too quickly. During our second term, we bought our own second-hand car. If we removed the air filter and gave it a good gun at the start, it would purr up the hill.

Julie: There was political instability. The local telegraph usually warned us when to stay in because of trouble. A friend missed the message one day. She was pregnant and anti-American protesters stopped her car in Lahore. When they saw that she was white, they grabbed the car keys and demanded she get out. In the commotion her driver snatched the keys back and sped off. She laughed and said, ‘That was close!’

In the late 1970s during the military coup against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, father of Benazhir Bhutto, we lived under curfew. Soldiers drove up and down the road in trucks with machine guns. You couldn’t go out. If you went out and didn’t stop when called, you would be shot. In the midst of this I had to drive a group of nurses to the airport in our combo van. The government issued a pass for me to drive the girls to the airport and back. I was stopped at every corner and had to produce the pass. I can tell you it was hairy. I didn’t have a bald patch before then!

Mission families went to Sandes, the school boarding house, in summer.

At the dedication (similar to baptism) of the children of three Salvation Army couples at Jhang.

Training College, Pakistan

After four years in Pakistan, we came home for four months and then returned for another four years. Rhys played with local children and expats. When he started school, Julie stayed with him at Sandes for three months. Then after nine months of home schooling he was ready for grade one and boarding. He loved Murree.

I was responsible for training new Salvation Army officers. We moved to the training college compound at Lahore. We ran overlapping two-year training courses with new intakes every year.

Julie: Imtiaz, the son of one cadet couple was deaf. We found that he had tuberculosis and arranged medical care and nourishment. He began to hear a little before he left. Some of the women struggled with training because their education had been focussed on domestic skills. We provided additional tuition in Urdu and were pleased to see them succeed as evangelists. We had great love for the young folk we helped to shape.

Boota, Rhys and Goga.

Kindergarten with Aunt Hill, 1980.

Imtiaz had tuberculosis.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected

Training College, Pakistan

There was an example of feeling God’s will. Our car needed a lot of work and we had to find the money to fix it, or sell it. We used the college’s van to transport our cadet students but we were uneasy about getting rid of our car and kept putting it off. We didn’t mention it to each other for a while. We asked the Lord what He wanted us to do.

In the end, we got the money to fix the car. But, when we took the car in to be repaired, the prices had gone up and we didn’t have enough. Lyndon told the repairer not to do it but the guy said, ‘No, I will do it. I know you, and I know that when you have the money you will give it to me’.

He was a Muslim and Lyndon said to him, ‘You had better pray about it and we will pray about it’.

He called Lyndon to collect the car when it was ready, even though we didn’t have enough money. The mechanic never expected you to pay the full amount for a few weeks, so you could try the car and be sure it was fixed.

Working with Rhys on car parts, 1982.

Taking a class outside, 1979.

Training College, Pakistan

The week that we were due to pay, we still didn’t have the money. Then a group that usually sent money for our work at a different time, sent us some money and said, ‘Spend it on yourselves’. It was the exact amount we needed for the car. You know when something is not right and you know when it is right. You feel that peace.

During our second term, Arthur Holland became the new commissioner for Pakistan after working for most of his life in Africa. Arthur was an important mentor to me. By example, he taught me about leadership and dealing with difficult situations. We became lasting friends with Arthur and his wife Louise.

We had decided to return to Australia after twelve years, for our son’s sake. After nearly eight years in Pakistan, we were asked to commit to another term. We both started to feel uneasy about it. We had said twelve years but we just knew it was not right. We told Arthur we wanted to go to Africa, but he needed us in Pakistan and wouldn’t release us. He said, ‘My counterpart in Africa wouldn’t want you. If we were willing to release you, it would mean you’re not much good’.

Then he became the officer in charge of all of Africa. I showed him a letter I had written when first posted to Pakistan. It said, ‘I’m willing to go to Pakistan but my real calling is to Africa’.

Then he suddenly changed his mind. He said, ‘If that feeling is so strong and it always comes through in all your paperwork, who am I to stop you going’.

That’s how we got to Africa. That was another way I think we knew God’s will.

We maintained contact with the Burrows, Steers, Bainbridges and Troedsons and John Jivanandham long after we left Pakistan.

Commissioners Arthur and Louise Holland.

The training college, 1982.

With Julie and Salvation Army cadets (trainee ministers) under the new flag, 1980.

Zambia

The buildings in our compound in Zambia were pretty solid. There were three missionary families and two local families at any one time. It was a big area and not cramped. The compound was surrounded by a seven-foot brick wall with glass and barbed wire on the top.

Julie: That was to keep people out because there was a lot of thieving. One lady was held up outside the gate of her compound. She refused to hand over her car keys and she was shot. The same thing happened to someone dropping their children off at school. But you learnt to be aware of what is going on around you and live with it.

Thieving was very bad in the capital Lusaka. At one point it was known that if you walked alone down the street, four men would each grab one of your limbs, rip your bags off you and drop you.

One time we were in a shop and someone broke into our car outside. The alarm was blaring. We stayed in the shop and the guy in the next car continued reading his paper. That was the closest we ever came to any trouble so we never felt unsafe.

Rhys did very well at the international day school in Zambia. He played with the local boys and spoke their language because they were his mates.

I was responsible for property. We would raise funds from outside Zambia and calculate building time and costs. We adapted the same plans for many building projects. I had about seven guys working with me. When the men pegged out the site, I would check that everything was square and ready to go.

Lusaka Corps, 1985.

Our house in Zambia. Headquarters office at Zambia, 1985.

Zambia

A foreman would stay with the group. He was good but they didn’t always get it right. When they were building a house for the chief secretary, and I went to check, all the windows were wrong and one side of the long hall was leaning inwards.

I also had to do the quantity surveying and pick up materials from South Africa. It was a two-anda-half-day trip, one-way, if you didn’t have to stop. It often took longer to get through the border crossings on the return trip. One official was a stickler for checking everything and its purpose.

When cars were due to be replaced, I changed them to Isuzu. I thought the Isuzu engine was better suited to Africa and I could get parts in Johannesburg. I had to wait six weeks for the parts for other Japanese cars.

One time, I ordered a car over the phone. When I went to Johannesburg, the sales representative invited me to take a test drive. I got in and turned the engine on. I turned the engine off and got out. I knew the problem immediately. I said to the agent, ‘You didn’t listen to my order. I didn’t ask for a petrol engine. I want a diesel engine. I won’t buy a vehicle with a petrol engine.’ He was ruffled, but we eventually settled on another vehicle that was available. He apologised for the confusion. I didn’t apologise for being me!

I would also buy supplies for the hospital and school at the Chikankata mission. I usually drove a utility truck. On one occasion I bought a 23-seater bus for the training college and drove it back, filled with supplies. I wasn’t licensed to drive passengers in it but there was no room for passengers. I was nervous on that trip because of the value of the bus and all the goods in it.

Our car on a South Africa trip.

One of the workers with Command Headquarters ute.

Chikankata mission.

Zambia

I drove through Zambia and Zimbabwe to Johannesburg and drove back through Botswana. It was challenging to navigate the different currencies. All our funding came from overseas in pounds. The export agent in Johannesburg dealt in US dollars. Zimbabwe used the zimdollar and Botswana used the pula.

Julie: We couldn’t buy butter in Zambia so we would cross over the border into Zimbabwe and bring it up.

She doesn’t mean vomiting, just to clarify the language.

Julie: In Zambia you could only buy flour on the black market so Lyndon bought flour in South Africa. He also bought porridge oats, and cheese in South Africa. In Zambia, the rule was that if it was on the shelf, you should buy it. You might not see it again.

We were in Zambia for four years.

Julie: We came home for the last time because Lyndon was working so hard. He was working 60 to 70-hour weeks and literally came home to eat and sleep. He said, ‘I just need someone to come and help me, someone who knows which end of the hammer to hold’. That was our expression and we couldn’t get anyone.

Finally, we set a deadline and said we wouldn't be able to renew our contract, because Lyndon couldn't keep doing it. Then they found someone. His wife came in and said, ‘He doesn’t know which end of the hammer to hold’.

On the road to Mbala.

Kariba Dam wall and crossing to Zimbabwe.

SAGALA

When we returned to Australia, I worked for the Salvation Army Guides and Legion Association (SAGALA). It took twelve months to organise a tenday camp for 300 fourteen-year-old guides and legion in the Adelaide hills. I had to prepare research and costings and apply for funds. I also designed a logo for shirts and organised all of that.

The group learnt bush survival skills and were assessed on that. We were there to support people and provide backup if necessary. The group also visited local areas of interest and held concerts. I met a lot of young people and teachers who were running programs for different groups.

When we were back in Australia, the boss here said to us, ‘You won’t get to go back overseas. You know that, don’t you? You don’t have a qualification. They don’t want missionaries overseas anymore’.

Julie: It was funny. We were on the mission field for twelve years and the whole time we were there, Headquarters was writing to London screaming for people to come out because they couldn’t get the people they needed. Lyndon spoke to someone he knew in London who said, ‘Let me know when you are ready to go and I will do something about it.' That’s when we went to Ghana.

I was given a plaque of appreciation at the camp. It includes the badge given to all participants and the Camp Australiana logo I designed.

Wearing SAGALA uniform.

Salvation Army youth workers at the MCG, 1980s, Lyndon second from right. The youth workers were involved in SAGALA, Divisional oversight of Sunday School and other youth activities.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected

Lyndon & his love of deserts

Ghana

Julie: In 1996 we went to Ghana. We were warned that the accommodation in Ghana was probably the worst you could be sent to. It was a very small flat. The kitchen had a shelf that curved in every possible direction. The drawers didn’t align with the cupboards below them. The cupboards caught your toes as they opened and were held shut with a stone. The fridge had given up the ghost so the men stapled in a new set of tubing. The internal freezer box had to be defrosted every week. The twin tub washing machine leaked and the pump didn’t work. You needed gravity to get the water out. That was the kitchen, and Lyndon completely transformed it. He also worked through the rest of the flat.

It was just a matter of finding out where to get things and putting it together. The window between what used to be the passageway and the kitchen had louvres, burglar bars and wire on it.

We worked in extension training. After someone was ordained through the training college they had to complete two years of extension courses. We ran refresher and development courses in doctrine, theology and organisational skills. Julie also provided information about women’s health and housekeeping. Then I was responsible for property as I had been in Zambia.

After nearly three years in Ghana, I was appointed chief secretary. That is like the assistant CEO of the Salvation Army in Ghana. The top guy has the vision and says what he wants to achieve. My role was to make it happen. I was a jack-of-all-trades.

New kitchen, 1996.

Builder at work, 1996.

Loungeroom before. That was how we lived. It was too hot to go outside.

Loungeroom after.

Lyndon Spiller: An

Julie: Everywhere we went, people asked him to fix their cars. Later, he would talk to the mechanics to check they were doing things properly. When he became chief secretary, we moved to a huge two-storey house. Lyndon built a desk in the office.

The bed was so big that we said we would have to telegraph each other to prove we were in bed at the same time.

Ghana

We moved around and met many people in different areas. Going into new places was like anyone visiting new people. Who are they? How does it work? Have I said the right things? It’s the same but with a slightly different feel about it. You get to know what they do and sometimes why they do it. Some people who work for the Salvation Army use swear words or smoke. I had to say, ‘That is not acceptable,’ or, ‘You can do better than that.’. Most times you would get some response.

A local chief attended one of our meetings and addressed the people after I spoke. He always sits on a special stool to signify that he is the chief. Later, the local people gave us stools. It was very special and I don’t know that it happened to anyone else.

Julie: Wherever we went, Lyndon got on well with people in Africa. The locals often expect that whites will play lord of the manor, but Lyndon was quite different. He was one of the team and always a joker. They respected him for hopping in and for his knowledge.

The Ashanti tribe are associated with gold and are considered to be the most powerful tribe in that part of Africa. When we were there, the Ashanti king was very well educated. He had been to England and Canada. He was quite a modern young man, which was new for the Ashanti kingdom.

He announced that he would attend the Salvation Army church service in the area of his palace. We went to represent Headquarters. After the service, tradition dictated that we escort him back to his palace. Then we were invited into the palace to meet him on his throne. The palace was like a very nice home.

Bedroom.

Office.

The local people gave us heavy wooden stools in recognition of leadership.

East Africa

In 2002, I became the chief secretary in East Africa. Including Kenya and Uganda, it is the Salvation Army’s largest territory.

We spent one or two weekends each month travelling around. It could take a whole day to travel there and another day to get back. We weren’t going that far but the roads were bad. Once, we drove along a dry river bed.

We went to Turkana. The Salvation Army usually provided a vehicle but the Turkana district didn’t have one. The guy there bought himself a motorbike and rode it everywhere in a harsh climate. But it meant his wife couldn’t travel with him to encourage women. I organised overseas funding to buy him a Land Rover.

Julie: It was so important. People had walked for half a day to put water in the tank of the corps officer at Kalokol. If there is no rain, there’s no rainwater in the tank, and there’s no stream and no piped water. People carried buckets of water so he could have water.

At Nariokotome corps, some people at the side of the road flagged us down. One of them was waving the Salvation Army flag. Ibrahim Lorot from Turkana said, ‘We’re not supposed to stop, but would you mind?’

We met a group who gathered under a tree. They used to have a hall made of sticks with a grass roof. But there was no grass in the drought so they couldn’t keep the roof. They were under the last tree because trees were constantly cut down for firewood. They didn’t know how long that tree would survive. Then they wouldn’t have anywhere to meet because it was putridly hot. One of our home churches had given us some money so we paid to have metal rods and a metal roof put up. They used it for everything.

Riverbed road.

Kalokol Quarters with water tank.

Original Nariokotome hall lost its grass roof.

The new Nariokotome structure.

Meeting under a tree at Nariokotome.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected

East Africa

The women at the Nairobi headquarters were fantastic. They had to know English if they were going to work in the international field. Some of them couldn’t read very well so I gave them a lot of old Readers’ Digests and asked them to read aloud. We would hear them practising. The Kenyans wrote us many letters when we left and a lot of the women said their English improved because of our encouragement.

We didn’t usually make many tourist trips, but we went to a lot of game parks in Kenya. At the Maasai Mara game park, two lions started walking towards our truck after their kill. They came right up to us, sat back and dropped to the ground. They slept in the shade of our truck. We also saw cheetah on their kill.

We stayed overnight at The Ark Lodge. The accommodation overlooks a waterhole and salt lick that attract wildlife. When special animals come to the waterhole in the middle of the night, the guards blow a horn to let you know. We stood behind a brick wall with viewing holes in it and watched huge elephants walk past. You could have hidden behind the ear of an elephant. But you didn’t.

Julie: We also walked among the giraffes, with a guide. Previously, people were allowed to walk among the giraffes on their own, but one guy got too close and the giraffe kicked and killed him. We used to take our visitors to a local giraffe farm in Nairobi where you could feed the giraffes.

We went to Tsavo game park, renowned for its association with Denys Finch-Hatton, played by Robert Redford in Out of Africa. After his hunting days, Denys became interested in conservation. For one night, we glamped in one of the best cabins, a five-star tent. It was named after Denys and overlooked the hippo pond. We were escorted to the cabin and then we couldn’t leave it until they escorted us out for meals.

Fothergill was an island in Zambia where I walked among the elephants with a guard. We had to walk and crouch, walk and crouch. When the elephants took notice of us, we had to stop and crouch and be still until the elephants went on with their business. It was an amazing place. We had two or three nights there.

Finch-Hatton, the five-star tent, at Tsavo.

Elephants at The Ark.

Ladies jumping as they dance.

Towards the end of the lion kill, the driver took us very close and Julie leant out of the truck to take photos.

Feeding a giraffe at a giraffe farm in Nairobi.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

The toolshed

When we retired back to Australia and came here to live, the only requirement was that the house had to have a decent size toolshed. The Salvation Army extended the shed.

I ripped out all the fittings and put in a new floor because it wasn’t level from the extension. Then I put in new walls and ceiling and installed benches and cupboards all the way round. I had pegboards and worked out places for everything. There were hideaways down below and I had an electrician run power out to the shed.

Julie: Lyndon did all his work overseas with a handsaw, a screwdriver and an electric drill. The drill was the only electric tool we had. When we came here, he decided he wanted to do some proper woodwork. We bought all the electrical tools, a saw bench, a drill press and set up a whole workshop. All the men who entered were amazed and perhaps envious. It was something to behold.

He did a couple of projects fitting out shelves for friends and family. He had planned to make good furniture. But then he started having trouble with his eyes and lost confidence working. He didn’t get to use some of the equipment and it’s all been sold off.

I always felt that he got his enjoyment out of making the shed, even if he didn’t get to make all the other things.

Rebuilding the toolshed, 2010.

Dementia

The dementia diagnosis came as a shock. I knew about it because both of my parents lived with dementia. When I was diagnosed, my main concern was forgetting things.

I rely on Julie to help me remember things properly. I always enjoy going to the Umbrella Café. It helps to be with people who understand.

Julie: It is hard to watch the progression of dementia. Lyndon increasingly struggles to put words together. He still has his sense of humour, but other people don’t always understand it.

Umbrella Café of Connections at Box Hill, 2024.

Lyndon Spiller:

Reflections

With a soldier (church member) at a special meeting in Migori, Kenya. He was so excited to have his photo taken.

When I was called to be a missionary in Africa, I wasn’t sure if I could do it. But I read and shared with others who were older and more experienced and realised I could follow the Lord. He would open a door or path where I could enter and become part of what He wanted me to be. God wanted me to be one of His people who spoke up because I wasn’t afraid to. That’s not me by nature. I am fearful. But it’s only driven me back to how the calling works.

Is it just my thinking or is a calling God’s way of dealing with those of us who are saying, ‘Lord, we are waiting for some direction, some possibility that we can fulfil so that others discover the gospel’.

Even now, going through the scriptures again helps me to understand what God wants me to be. He wants me to be honest and open. If I’m honest and open, I can help you. If I’m honest and open and you run away, I can’t do anything about it. My calling is to do what God wants me to do.

There are a number of ways God speaks to us. And it’s a matter of saying, ‘Lord, I’m available and I’m prepared to be available at any time and any place’. That’s a pretty big marker. Sometimes I say, ‘It’s okay. I’ll just be strong and keep my eyes on God and see His will in every situation’. Each time I went forward I felt as though I dropped back a fraction as well. I have to do this but if I drop back here, that’s more solid.

There are a number of times the Lord has spoken to me and I’ve said, ‘Yes Lord, let me follow it through’. Then I try to follow it through. Sometimes I ask my wife and she translates things for me.

Sometimes I have to ask the Lord, ‘Is this really what you want of me?’

Then I go, ‘Okay then.’

And it feels right, even though you might look at it and say, ‘Isn’t he brave!’

Someone once said, ‘We’re not quite sure whether we think you’re wonderful or we think you’re mad’. I thanked them for their honesty.

I was a jack-of-all-trades. I didn’t have the usual qualifications to be a missionary but I knew about cars, refrigeration, technical drawing and other practical things. When I went overseas, they were the skills I needed.

This one is beyond repair!

Building each other up

It was also important to connect with people. I worked with people one by one because everyone is at different levels. I encouraged them to be their best person and to pursue education and general learning. I encouraged them about their leadership roles. Many of them referred to me as their mentor. Later, most of them became leaders in Salvation Army territories around Africa.

In Ghana, I encouraged Samuel Anponsah in finance work. He was very keen to learn but it was hard for him to learn in Ghana because they didn’t have the teaching capacity. Eventually I was able to get him to London to study. He became the top guy in

Samuel Amponsah Dip BRS, BTh, MICA, FCCA, MBA, MSc.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Building eachother up

Ghana.

Julius was a chaplain at the airport and I encouraged him to study. Now he has a master’s degree and runs the Salvation Army university. He says that I sparked his interest in learning and I was the first one to send him overseas, to an airport chaplains' conference.

Marion was a gem-and-a-half. She was only a young girl but she took over editing the War Cry, the Salvation Army magazine. I encouraged her and now she has a degree in trauma counselling and often goes overseas to conferences.

We want to build each other up and work for each other so that God’s kingdom is growing. I spoke to people about their calling and opportunities. What opportunities does God give you here? Do you see this as an opportunity? How do you see this as an opportunity? And if it works, what are you hoping to get out of this?

What was I hoping to get out of this? A Julie.

Marion Ndeta.

Julius Omukonyi.

Commission

Transport

of officer in Kenya.

at Shigomare, Kenya.

Men’s fellowship at Nakuru, 2003.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Julie & Lyndon.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling

Back, Catherine and Rhys; front: Julie and Lyndon.

With grandson Josh.

With granddaughter Beth.

Lyndon Spiller: An Unexpected Calling