RESILIENCE+ ADAPTATION

showcased in this issue: STUDIOS

THESIS EXCERPTS and FIELDWORK

including conversations with: UPROSE, Courtney Knapp, Ron Shiffman, Ira Stern

20212022 The Student Magazine of Pratt Institute’s Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment

10 Years After Superstorm Sandy

by Semire Bayatli & Walker Johnston (UPM)

Reimagining Our Streets: What We Resisted, Adapted, and Reclaimed in Brooklyn

by Semire Bayatli & Walker Johnston (UPM)

Envisioning a Community of Care in The Bronx

by James Tschikov & Kevin Garcia (CRP)

Community Love Over Capitalism

by Mariah Chinchilla (CRP)

Rising Tides, Rising Rent: Connecting Climate Justice to Social Housing in New York by Alex

Miller (SES)

Community-Based Alternatives to Watershed Planning and Development in the Lowcountry by Amron

Lee (CRP)

Reclaim/

Reuse/ Recycle! by Ethan Brown, Mahnoor Fatima, Tara Hopp, Megan Maize, Katherine Pioch, Diego Rivandenra, Alison Weidman, Jeremy Ziegler

Challenges to Fresh Food Availability in Coney Island and Opportunities for Inclusive and Sustainable Land Use through Community Gardening

by Nana Acheampong (CRP)

The Impermanence of the Vodou Religion in the Haitian Diaspora

by Claude Jeffrey Charles-Pierre (HP)

Holistic Wellbeing: Two Case Studies in Affordable Housing

by Browne Sebright (CRP)

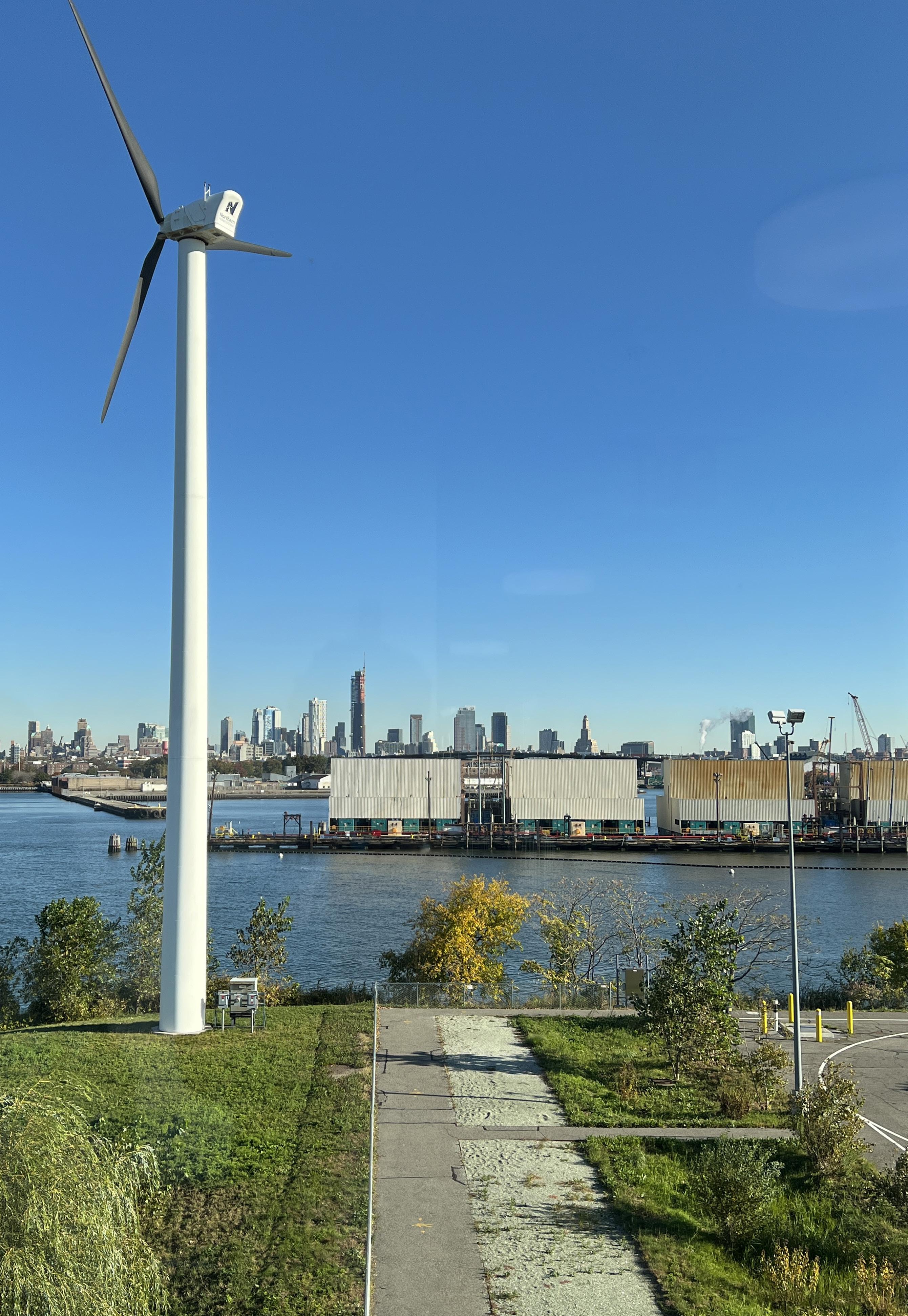

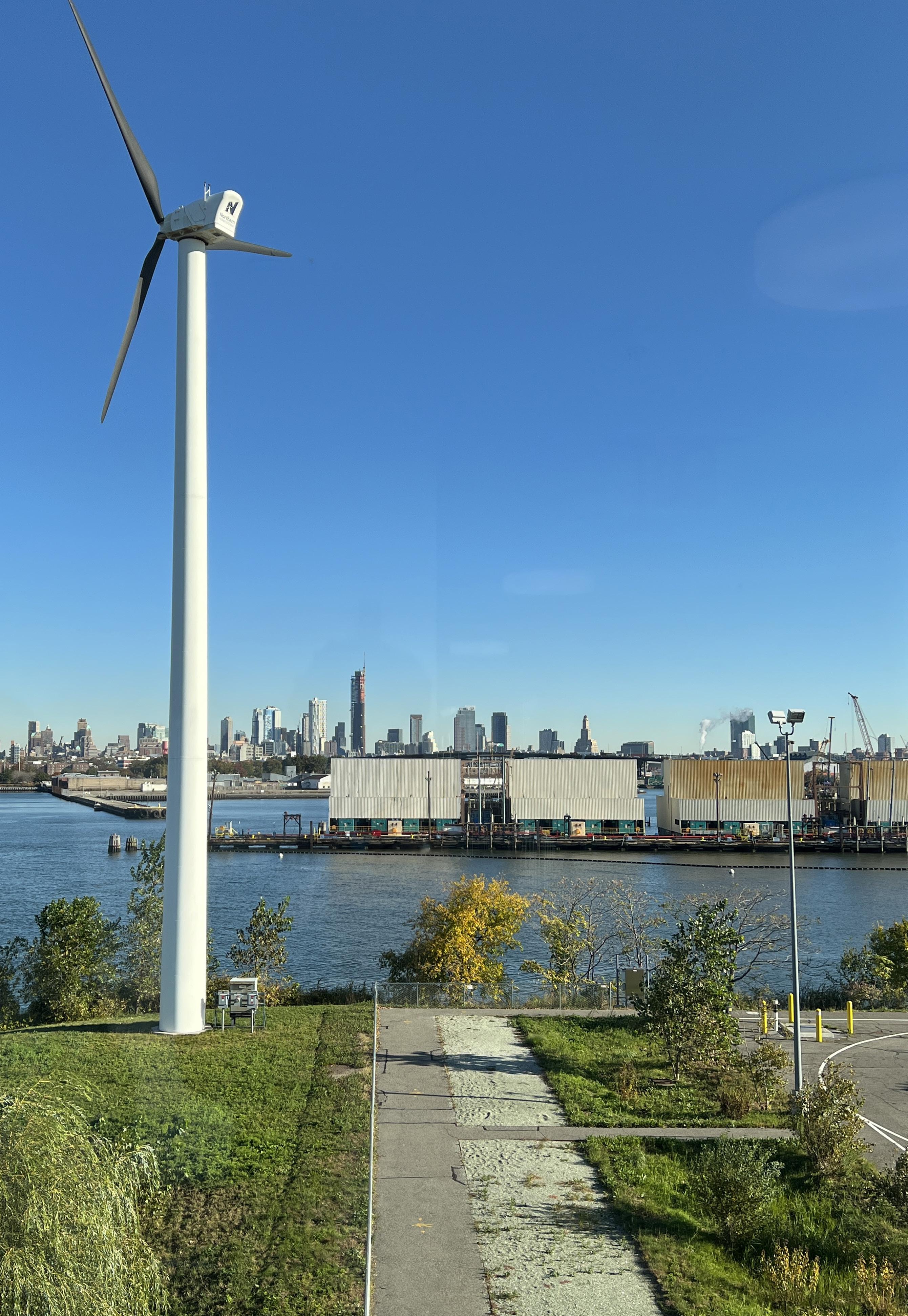

Towards a Just Transition for the Industrial Waterfront by James

Tschikov (CRP)

02

44

table of contents [CRP: City and Regional Planning] [HP: Historic Preservation] [SES: Sustainable Environmental Systems] [UPM: Urban Placemaking and Management]

06 16 22 30 36

50 56 66 74

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear Fellow Students,

The theme for the 2022-2023 edition of MultipliCity is resilience + adaptation, threads which undoubtedly pervade all four programs of the GCPE. We wanted to raise awareness about climate change that affects the whole world and share case studies illustrating the challenges, opportunities, and successes when it comes to climate change adaptation. This edition, which we have prepared during the 10th anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, consists of thesis excerpts and reflections prepared by GCPE students, studio case studies, fieldwork, and resilience and adaptation-centered articles.

Importantly, this publication aims to approach resilience + adaptation with a holistic lens. Each piece included in this year’s issue touches on different facets of resilience + adaptation in our disciplines. Articles contemplate: how are communities creating networks of care and deepening their resilience through affordable housing? How are we as a city and collective continuing to adapt to an ongoing pandemic? How can place-based heritage be preserved as communities evolve and adapt? And, critically, how are we moving beyond climate resilience to imagine transformative futures for frontline communities?

In crafting this edition of MultipliCity we were struck by the ways in which resilience + adaptation are embedded within our work and how these terms continue to evolve. We hope this sampling of material inspires you to reflect on our individual and collective responsibility in striving for a more resilient and just world. We would like to thank the GCPE and faculty especially our Department Chair Eve Baron, UPM Academic Coordinator David Burney, and Professor Emeritus Ron Shiffman for their generous support in this endeavor.

We believe in collective effort, as Ron Shiffman said, “People change, people go, people die; but if you can sustain the effort, the network and the organization will continue to serve their true purpose.” As part of the GCPE family, we believe that we are all part of the same effort and wish you success.

SEMIRE BAYATLI UPM ’23

WALKER JOHNSTON UPM ’23 JAMES TSCHIKOV CRP ’22

61 St. James Pl. Brooklyn, 1238 www.pratt.edu/gcpe

SEMIRE BAYATLI UPM ’23

WALKER JOHNSTON UPM ’23 JAMES TSCHIKOV CRP ’22

61 St. James Pl. Brooklyn, 1238 www.pratt.edu/gcpe

10 Years After Superstorm Sandy

PRATT INSTITUTE’S RESILIENCE WORK AND THE ORIGINS OF THE RAMP INITIATIVE

by Semire Bayatli and Walker Johnston

INTRODUCTION

Late October to early November of 2022 marked the ten year anniversary of Superstorm Sandy, the largest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded, that left a path of devastation—communal, physical, and emotional—along the eastern coast of North America from the Caribbean to Canada. The most populous city in the United States was not exempt from the destruction; in New York City, at least 43 people died, thousands of homes and businesses were damaged, and major flooding and electrical outages impacted households across the metro region, all causing billions of dollars in damage. The disaster forced affected communities to reckon with their own vulnerability to climate change and to focus on planning for increasingly more frequent severe storms. The New York City government took action by “establishing a Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, developing berms and levees along its shorelines, and restoring wetlands.”1 At Pratt Institute, students and professors mobilized, forming the The Recover, Adapt, Mitigate, and Plan (RAMP) project, an initiative which still exists today; its mission is engage with with “frontline waterfront communities in New York City to co-create and accelerate values-based, equitable, innovative, and effective strategies to recover, adapt, mitigate, and plan for the impact of the climate crisis.”2

This article details the formation of the RAMP initiative and is based on an interview, edited for brevity and clarity, with Ronald Shiffman in October 2022.

1 Afridi, Lena P. “10 Years After Sandy, Renters Remain Most Vulnerable to the Impacts of Climate Change,” October 28, 2022. https://www. thenation.com/article/environment/10-years-after-sandy/.

2 “RAMP22 Home.” RAMP Site (blog). Accessed November 24, 2022. https://ramp-pratt.org/.

3 Ibid

2FIELDWORK MULTIPLICITY

Flooding in Red Hook after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Photo by Tyler Sparks, Curbed

RAMP ORIGINS

The RAMP initiative formed from a group of Pratt students’ collective reaction to what was the devastating impact of Hurricane Sandy. The disaster required emergency response, and many students contributed by preparing food for frontline workers and isolated community members. Amidst these activist efforts was a sense of both hope and anxiety, along with motivation to do more than making sandwiches—a drive to take action to help communities become more resilient with the threat of future storms.

Faculty in the programs for Sustainable Planning and Development (PSPD)—now the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE)— and Undergraduate Architecture created the RAMP project with this forward-looking viewpoint. Pratt Institute GCPE Professor Emeritus Ron Shiffman, Jaime Stein, and School of Architecture faculty including Zehra Kuz and Deborah Gans, were among RAMP’s founding leaders.

Early work concentrated on coastal communities most impacted by Sandy, including Sheepshead Bay, Red Hook, Coney Island, and the Rockaway Peninsula in Brooklyn and Queens. Collaborative workshops and training sessions, working groups, and academic curricula—including the current Delta Cities Coastal Resilience joint studio in the GCPE and Undergraduate Architecture departments—molded RAMP’s framework. While undergraduate architecture students thought about what new design strategies may make living with and on the water sustainable, planning students created policy proposals.

INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

From Spring 2013 through Fall 2014, graduate and undergraduate studios were set up with funding from the Kresge Foundation to study how to adapt and safeguard shoreline communities in the face of increasing sea levels, severe storms, and habitat loss while preserving their historical identities. Direct engagement, relationship and trust-building, collaboration with community groups in the impacted areas were essential to this. Additionally, RAMP was intentionally designed as an interdisciplinary undertaking, operating with the understanding that change could not occur through solitary labor. Superstorm Sandy served as a stimulus to bring students across disciplines together, which resulted in a new array of classes working on the same projects with the same communities. The classes would meet up to share with one another what they were learning, representing a new pedagogical approach of weaving curricula together. This approach continues at Pratt today.

“Participation must be multi-faceted and has to carefully weave together a set of values that recognize diversity, equity, and justice, addressing the needs and engaging the voices of all impacted. The process of planning is as important as the products of that process and, indeed, if the process is well designed the end product—the places we live in, work in and embrace—will be far better.”

3FIELDWORK MULTIPLICITY

3

- Ron Shiffman

Pillars of RAMP

Community is an important pillar of the RAMP initiative. RAMP aims to be a model for communitydriven academic partnerships, and a way to build capacity to address the present and future climate crises. Significantly, the initiative seeks to highlight the interrelationships of social, racial, and climate injustice— acknowledging that the regions most impacted by climate change are typically low-income communities of color. At the root of the RAMP initiative is a spirit of co-creation and drive to bring together Pratt students, faculty, and local community leaders to create participatory design solutions addressing environmental, social, and economic pressures that can be implemented and replicated in other communities. Ron emphasizes the need for “culturally appropriate public participatory tools that engage people in planning and development processes in such a way as to minimize their alienation and enable them to benefit from all stages of the development process—including being beneficiaries at the end of the process.”4

THE PRATT ETHOS

Embedded in the fabric of Pratt Institute as we know it today is the ethos of community engagement and co-creation. According to Ron, the vision behind this is the belief that the work of architects and planners should be made available to everyone. This approach emerged in the 1960s as a backlash against the school’s curriculum, which focused on esoteric projects that lacked any relation to the declining communities surrounding the Pratt campus. Students in the School of Architecture went on strike to protest the disconnect between the curriculum and communities, and things started to shift.

The Pratt Center, founded in 1963 as the first university-based community planning organization in the United States, embodies this ethos. The center engages on the ground with community-based organizations to combat systemic injustices and foster sustainable development. It does this by utilizing professional talents in urban planning, architecture, design, and public policy. The objectives of the RAMP Initiative and the Pratt Center are both based on the conviction that achieving a community's vision and dislodging stagnant paradigms result from challenging inequities, making courageous decisions, and being receptive to the possibilities that a process of collaborative exchange can produce. Both the planning field and academia have a reputation and history of being extractive, using residents for their research and leaving them with participation fatigue and little to no concrete improvements to their communities. The recognition that partnerships with communities must be sustained beyond the academic calendar is fundamental to RAMP’s approach and lasting impact on the GCPE operations.

4FIELDWORK MULTIPLICITY

FEATURE

4 Shiffman, Ronald, 2021, unpublished, “People, Pandemics, Planning and Participation.”

LOOKING FORWARD

From Ron Shiffman’s personal perspective, consistent effort remains the most important ingredient for success with the RAMP initiative. RAMP illustrates how the path forward in disaster planning, resilience, and adaptation must be a steady, collective effort, built by deep collaboration and leveraging resources across disciplines and communities.

5FIELDWORK MULTIPLICITY

Let The Water In; Srategies for a Resilient Edgemere. Photo by DCCR Studio 2019.

“People change, people go, people die; but if you can sustain the effort, the network and the organization will continue to serve their true purpose.”

- Ron Shiffman, Professor Emeritus, Pratt School of Architecutre, GCPE

FEATURE

Envisioning a Community of Care in The Bronx

A PILOT PROJECT FOR CAREGIVER AFFORDABLE HOUSING FOR A RESILIENT ECONOMY (CAHRE)

By James Tschikov and Kevin Garcia PLAN 820 Land Use & Urban Design Studio

FACULTY

Mercedes Narciso

Jina Porter

Eva Hanhardt

Ayse Yonder

STUDIO MEMBERS

Agata Naklicka

Amelia Clark

James Tschikov

Kevin Garcia

Kieran Micka-Maloy

Leanna Molnar

Lindsey Cassone

Matthew Marani

Michaela Brocchetti

Natt Slober

Nischala Namburu

Rita Musello-Kelliher

Shelby Ketchum

Suzanne Goldberg

INTRODUCTION

Community resilience comes in many forms and affects various sectors of our population. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed gaps in critical infrastructure that presented challenges in public health, community care, workforce, and housing for New York City leaders to address in the years to come. Today, there is a rising need for athome healthcare that is a direct result of the aging and disabled population. New Yorkers aged 65 and older are projected to grow by approximately 41 percent by 2040.1 This is coupled with the overworked, understaffed, and under-resourced home care workforce, who are critical to providing healthcare for the elderly and people with disabilities. The high turnover rate within the homecare industry, as well as the more than 20,000 job openings in the field, are a result of the myriad challenges faced by workers, including low wages, long commute times, and gaps in basic support.2

The Caregiver Affordable Housing for a Resilient Economy (referred to as CAHRE) is a concept based on a nexus between community healthcare needs and the provision of deeply affordable housing for low- and moderate-income healthcare providers. The Pratt GCPE Spring 2022 Land Use and Urban Design Studio built upon the initial framework of the model introduced by the Collective for Community, Culture, and Environment (CCCE) and developed proposals for holistic community care infrastructure working with 1199 SEIU and Highbridge Community Development Corporation (HCDC) in The Bronx. The studio team investigated the need for an integrated care network, approached housing design through a feminist lens, and expanded beyond the limitations of affordable housing programs to develop an equitable model for vulnerable workforce populations.

7MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

1. “Health of Older Adults in New York City” (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, June 2019), https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/episrv/2019-older-adult-health.pdf. 2. “Fastest Growing Occupations,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, September 8, 2021), https://www.bls.gov/emp/graphics/fastest-growing-occupations.htm.

BACKGROUND & CONTEXT

Four faculty members who led and advised the student’s work throughout the studio are a part of The Collective for Community, Culture, and Environment (CCCE) who developed the CAHRE concept. The CCCE is a women-owned and led planning, architecture, and urban design practice and interdisciplinary professional network based in New York City, with projects throughout the tri-state region driven by their mission to develop a sustainable and equitable world.

The CAHRE Model provides strategies that uplift care workers, while also raising awareness of the challenges that this workforce of “Home Health Heroes’’ endured during the COVID-19 pandemic within existing housing and healthcare systems. CAHRE creates opportunities for home healthcare workers to live in close proximity to their clients, facilitates social infrastructure, and encourages community support.

The CAHRE concept developed by the CCCE addresses various elements of infrastructure:

• Hard Infrastructure: The physical systems of housing, open space, and transportation.

• Soft Infrastructure: Institutions that help maintain a healthy economy, which include investing in human capital and serviceoriented systems, such as education, health, finance, security, government, and more.

• Critical Infrastructure: Assets defined as the most crucial to a functioning economy, such as shelter, public health, food, etc.

“Care workers, who are mainly people of color, women, and immigrants, are the backbone of society, especially at times of emergency but their work is undervalued, underpaid, and ignored. CAHRE model addresses the affordable housing issue from a class, race, and gender perspective.”

A PILOT FOR HIGHBRIDGE, BRONX

Highbridge, Bronx was selected for the pilot project of the CAHRE concept due to the high number of home healthcare workers who reside in the neighborhood, and it being a more affordable NYC neighborhood for those working on a lower-wage salary.

As a client of this studio interested in piloting the model, the Highbridge Community Development Corporation (HCDC) owns and manages a stock of senior housing, and has extensive experience developing new housing. HCDC was interested in working with 1199SEIU to help residents become healthcare workers closer to clients needing care.

MULTIPLICITY8STUDIO

– Ayse Yonder & Eva Hanhardt, Studio faculty and CCCE Consultant

In the last decade, the housing shortage in New York City has caused a significant increase in housing costs, in addition to increasing concerns about speculation, maintenance, and overcrowding. Homecare workers face the brunt of these challenges as the majority of the workforce are women, over 70 percent are Black or Hispanic, 80 percent are foreign-born, and 72 percent live in multi-generational households.3 Furthermore, homecare workers struggle with low wages, with a

To understand the needs of the community, the studio conducted three focus groups: one with home health aides from Highbridge, one with home health aides from across NYC, and one with seniors living in HCDC buildings. Focus group participants answered questions about costs of living, housing conditions, community amenities, mobility, and emotional connection to the community and work.

Some major takeaways were that home health aides are dedicated to their jobs and love helping people, often staying later than expected to assist their clients; however, they endure long commutes, are underpaid, and lack employment stability. Highbridge seniors enjoy their neighborhood and its sense of community, but expressed a desire for more nearby amenities since traveling across the neighborhood’s hilly topography is difficult. Overall, home health aides serve as the first line of care for millions of people, yet they are severely undervalued, underpaid, and excluded from the traditional health care system.

median annual income of $22,000.4 This speaks to the critical need of the CAHRE concept to address these disparities by ensuring permanent housing affordability and long-term community stability for home health aides and their clients alike. Through a pilot project for the CAHRE concept in The Bronx, the studio aimed to establish the feasibility of this model citywide through the social housing proposal and community care networks.

9MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

3. “Home Care Workers: Key Facts (2016),” PHI National, September 1, 2016, https://www.phinational. org/resource/home-care-workers-key-facts/.

4. Isaac Jabola-Carolus, Stephanie Luce, and Ruth Milkman, “The Case for Public Investment in Higher Pay for New York State Home Care Workers: Estimated Costs and Savings,” CUNY Academic Works (CUNY Graduate Center, March 2021), https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/682/.

ENVISIONING A NEW SOCIAL HOUSING MODEL FOR NYC

Building on lessons learned from the existing conditions research, the studio developed six main components of the CAHRE Model: housing type and financing, participatory planning, design considerations, community services, ground floor commercial, and operations and maintenance. Each part of the model formed a framework that could be feasible in neighborhoods across New York City.

Social housing is a model that ensures permanent affordability, social equality, and democratic resident control by shielding housing from market pressures.5 This studio proposes that the CAHRE Model be implemented as a social housing program to avoid the competitive and unsustainable Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which does not allow for permanent affordability.6

In a Social Housing program, land acquisition and construction would be subsidized by the city’s floating bonds, investing directly in the project.7 Buildings would be owned by the City and managed by either HCDC or 1199SEIU, allowing for greater flexibility in area median income (AMI) thresholds and permanent affordability. Opening the housing to all essential workers would allow professionals from various AMI thresholds to subsidize operations and maintenance costs.

A land bank could provide land at a low cost to the city, requiring less upfront investment. The NYC Comptroller Brad Lander is advocating for a citywide land bank and a CAHRE project could serve as a pilot development on a land bank lot.8 In the long term, the land could be transferred to the community through a Community Land Trust, perhaps in partnership with the existing Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards CLT.9

Neighborhood-Specific AMI

Creating neighborhood-level AMI can create truly affordable housing that would make CAHRE successful. Currently, HUD calculates the median income for every metro region. In 2019, the 100 percent AMI level for the New York City region, which includes Putnam, Rockland, and Westchester Counties, was $106,700 for a family of four,10 but carve-outs for Westchester and Rockland Counties11 have allowed for developers to build affordable buildings at higher thresholds to cover operating costs. While a citywide AMI may not help, a Highbridge-or Bronx-specific AMI carve-out would reduce income eligibility for affordable housing permitting more rental units with deeper affordability and providing homes for home care workers.

10MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

Social Housing in Vienna. Photo by Margherita Spiluttini, Architekturzentrum Wien

Essential Workers

Low AMI Essential Workers

Home Care Workers

CAHRE as a Community Facility

Home care workers are critical to care infrastructure. If CAHRE housing is labeled as a community facility per the NYC Zoning Resolution, housing for these workers could fall under this definition.12 There are 2 approaches to categorizing CAHRE Housing as a community facility. 1) Leverage the precedent of supportive housing to define CAHRE housing as an institution with sleeping accommodations. 2) Categorize housing for home care workers near senior housing through a zoning amendment. These approaches use the classification of non-profit hospital dwellings as community facilities.13 Ultimately, these approaches require 1199SEIU to act as a housing developer or manager, which has precedent in their development of 1199 Plaza in East Harlem in 1975.14

WorkForSocial Housing

The proposed model combines the concepts of Social Housing and Workforce Housing. The “Workforce” denotation refers to the tenant housing demographic, while “Social Housing” is the Financing Model. This ambitious vision requires regulatory changes and advocacy by 1199SEIU. For protection, 1199SEIU would manage the building and provide union priority to home care workers by categorizing it as a community facility. Integrating a credit system into union benefits could help home care workers with families to pay for their larger rental units, which tend to be more expensive. Using the money generated through the credit system to pay back the construction loan can keep larger units more affordable without increasing rent.

“Social Housing in the U.S.,” Community Service Society of New York, February 18, 2020, https://www.cssny.org/news/entry/social-housing-in-the-us.

6. Stephanie Sosa-Kalter, “Maximizing the Public Value of New York City- Financed Affordable Housing,” Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, October 10, 2019, https://anhd. org/report/maximizing-public-value-new-york-city-financed-affordable-housing.

7. “Vienna’s Unique Social Housing Program,” Office of Policy Development & Research PD&R Edge (HUD USER, 2014), https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_featd_article_011314. html.

8. Sarah Holder, “Staking New York City’s Future on Social Housing,” Bloomberg CityLab, January 29, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-29/a-plan-to-boost-public-housingin-post-covid-nyc.

9. “Community Land Trust,” South Bronx Unite, accessed November 14, 2022, https://www. southbronxunite.org/community-land-trust.

10. “AMI - New York - Hud Effective Date 042419 - Safeguardcredit.org.” AMI - New York - HUD effective date 042419. The SafeGuard Group, April 2019. https://www.safeguardcredit.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/02/AMI_Safeguard.pdf.

11. Murphy, Jarrett. 2017. “The Secret History of Area Median Income.” Shelterforce. April 25, 2017. https://shelterforce.org/2017/04/25/secret-history-area-median-income/.

12. “NYC Planning Zoning Resolution,” NYC Department of City Planning, 2021, https://zr.planning. nyc.gov/. 13. Ibid.

14. Adam Thalenfeld, “1199 Plaza,” NYC URBANISM (NYC URBANISM, April 30, 2018), https:// www.nycurbanism.com/brutalnyc/1199plaza.

11MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

5. Oksana Mironova and Thomas J. Waters,

DESIGNING FOR COMMUNITY CARE INFRASTRUCTURE MODELS FOR URBAN DESIGN

NEW BUILD MODEL: A COMMUNITY HUB

The CAHRE model incorporates a feminist, working-class lens to address the current housing shortage for care workers. This hybrid development model incorporates standard and shared living spaces to be adaptive to care work and provide flexible commercial spaces. To achieve a radical re-imagining of housing for home care workers, some challenges must be overcome, including the lack of vacant lots in a densely populated area, construction costs for building a new development, and existing policy and financing constraints.

From three viable sites across the Highbridge neighborhood that were identified, the site on Ogden Avenue and 167th Street showed the most potential as a community hub. Although some of the neighboring lots are privately owned, HCDC could work with the owners to acquire the lots and offer opportunities to provide community benefits. If all the lots are acquired, a building with over 200 units can be constructed

on the site. Due to many homecare workers living in multi-generational households, the studio recommended that units built be two-bedroom and three-bedroom apartments with balconies and flexible layouts. The studio also included a small portion of efficient micro-studios that would open up to communal spaces for shared amenities to attract younger individuals to the field, provide a low-cost efficient living, and serve as entry housing for recent immigrants.

The site’s commercial zoning permits ground-floor retail or additional community space that could add to the area’s vital facilities and amenities, such as a daycare center and grocery stores, that can integrate with potential new open space to provide more community benefits. Lastly, the studio recommended using massive timber and passive housing design to drive down construction costs, reduce carbon emissions associated with new construction, and save on heating and cooling costs.

12MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

SITE FEASIBILITY

Highbridge CAHRE Model site plan for proposed development on Ogden Avenue and 167th Street. Source: Pratt GCPE Spring Land Use Studio, 2022

Developable square footage per lot

Developability including grade, terrain, and vacancy of lot

Commercial overlay zoning

Ease of lot acquisition

Proximity to transit

Access to parks and open space

Low environmental hazard

Proximity to grocery stores

Proximity to schools and daycare

Promixity to senior facilities

ADAPTIVE REUSE MODEL

The adaptive reuse approach to the CAHRE model is a form of redevelopment that focuses on renovating, upgrading, and retrofitting existing residential buildings, and considers adaptive reuse to repurpose commercial or community buildings. By utilizing this approach, developers can reduce their environmental impact, preserve the heritage and identity of the neighborhood, and save money on costs associated with demolition, construction, and new materials.

Retrofitting a building can also lead to healthier and more sustainable living environments. Investments, such as high-performance building envelopes and thermostat controls, can reduce energy costs to make for warmer winters and cooler summers. Meanwhile, electrification of cooking, heat, and hot water systems eliminates the harmful air pollutants that many routinely breathe in homes.15 Solar energy and battery storage reduce energy costs and make electricity resilient to grid-wide outages.

The studio focused on two of three potential sites, 987-989 Ogden Avenue and 368 E 148th Street. Notwithstanding both sites’ individual limitations, the sites were chosen due to their close proximity to existing community facilities, open green space, and transit. To meet the needs of home care workers using two-bedroom layouts of 1,100 square feet and three-bedroom layouts of 1,400 square feet between, the studio determined between 13 and 17 apartments can be built at 987-989 Ogden Avenue, and between 11 to 14 apartments can be built at 368 E 148th Street. Furthermore, using the ground floor for commercial purposes could produce additional monthly revenue to help maintain ownership of the building or offset home care workers’ rents.

13MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

15. “8 Elements of a Green and Healthy Home,” Green & Healthy Homes Initiative, November 6, 2020, https://www.greenandhealthyhomes.org/homeand-health/elements-green-healthy-home/.

NEIGHBORHOOD CARE NETWORK

The neighborhood care network model fuses the new build and adaptive reuse models to distribute housing units among multiple buildings with newbuild community facilities and create connected, healthy, and resilient communities. Integrating housing for home care workers throughout the neighborhood creates a flexible and replicable network of various housing types, resources, and services to provide individualized tenant support to meet tenant needs in different locations. This model can prioritize filling individual apartment vacancies in existing residential buildings, which will reduce expensive upfront costs.

This model employs a phasing approach that begins with a unit placement program, similar to the new build model, and progresses to building out a brick-and-mortar network of services in vacant and underutilized sites throughout the neighborhood. Existing sites suitable for this network model should contain residential square footage, be near accessible subway stations, and neighbor existing community facilities. These facilities should include services such as childcare, workforce training, and home care resource centers.

The studio spotlighted two potential sites to meet some essential needs identified by home care workers. The first is 1400 Cromwell Avenue, an R8A zoned lot, fit for a resource center on the ground floor and housing units above. The second location, located on the corner of Edward Grant Highway and Plimpton Avenue, could be built for seniors and achieve another goal of the CAHRE model. This lot is situated near other HCDC properties and can include senior-focused amenities.

“CAHRE model imagines a communitybased health and care system for creating healthy, resilient, and caring communities in the future. Providing deeply affordable housing for healthcare workers as part of basic neighborhood infrastructure would address their housing needs, freeing up time and opportunities by living in proximity to their potential clients. It would address health care needs of the rapidly growing senior and disabled population, and the community, especially at times of emergency.”

– Studio Faculty and CCCE Consultants

14MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

Proximity analysis of youth facilities for home care workers for the Neighborhood Care Network model. Source: Pratt GCPE Spring Land Use Studio, 2022.

CONCLUSION

This studio’s proposals and recommendations would strengthen and expand neighborhood infrastructure by incorporating an undervalued but critical workforce into the healthcare system. Through the development of deeply affordable housing with dignified accommodations and vital amenities, the CAHRE Model allows communities like Highbridge to establish a localized care workforce and cultivate neighborhood-based resilience. The three proposed models are examples of how to implement the CAHRE Model in New York City and beyond to allow home health aides to care for their neighbors, clients, families, and, most importantly, themselves.

Community Love Over Capitalism

A REFLECTION ON THE RECOVERY OF NYC’S NIGHTLIFE ECONOMY

by Mariah Chinchilla

by Mariah Chinchilla

Summer 2022: A time and space where the history of house music, Beyoncé, and the state of our urban cities can coexist. In the two years since I completed my thesis, titled “Barriers, challenges... in NYC,” the idea of land use as a tool that systematically displaces nightlife culture is no longer a fringe issue; it has become a movement spurring policy changes to ensure its survival and a nucleus for emerging solutions to solve intersectional urban planning issues.

Cities across the United States are reckoning with the radical disparities that they have perpetuated (see: 'A Lesson in Discrimination': A Toxic Sea Level Rise Crisis Threatens West Oakland by Ezra David Romero for KQED KQED1) through policy, land use regulation, and resource or funding allocation. The cracks in the systems that run our cities gave in when hit simultaneously with the COVID-19 global pandemic, the persisting climate crisis, and the scramble to achieve racial equity all at once.

In my research, I wanted to explore how mainstream culture, fashion, and music begins in spaces like after-hour art venues, bars, restaurants, and nightclubs, and how the existence of these places provide a sense of belonging for many people, but especially for Black, Indigenous, and persons of color (BIPOC). In NYC, nightlife is a sacred environment where one makes connections and finds community. By exploring the historic nexus between cultural movements and participation in nightlife, the study found night spaces play a critical role in nurturing social movements and civic participation including but not limited to civil rights, Gay Liberation, reproductive rights, education, and Black Lives Matter. However, what it also found (and what I innately knew), was while BIPOC and other marginalized populations are often the creators, originators, and pioneers of emerging trends, they are also more likely to be vulnerable to illegal harassment2 and over-policing that leads to the displacement and suppression of culture.

A night out on the dancefloor of Nowadays NYC in Queens. Photo by Mariah Chinchilla

1Romero, E.D. (2022) 'A lesson in discrimination': A toxic sea level rise crisis threatens West Oakland, KQED. Available at: https://www.kqed.org/science/1980255/a-lesson-in-discriminationa-toxic-sea-level-rise-crisis-threatens-west-oakland (Accessed: October 22, 2022).

2 Becker, J. and E., Conte. (2018). Flawed Findings Part I: How NYC’s Approach to Measuring Residential Displacement Risk Fails Communities. Pratt Center for Community Development Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.prattcenter.net/research/flawed-findings

A night out on the dancefloor of Nowadays NYC in Queens. Photo by Mariah Chinchilla

1Romero, E.D. (2022) 'A lesson in discrimination': A toxic sea level rise crisis threatens West Oakland, KQED. Available at: https://www.kqed.org/science/1980255/a-lesson-in-discriminationa-toxic-sea-level-rise-crisis-threatens-west-oakland (Accessed: October 22, 2022).

2 Becker, J. and E., Conte. (2018). Flawed Findings Part I: How NYC’s Approach to Measuring Residential Displacement Risk Fails Communities. Pratt Center for Community Development Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.prattcenter.net/research/flawed-findings

According to the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA), which represents almost 2,000 music and performance venues across the U.S., an estimated 90 percent of venues were faced with the possibility of permanent closure due to the pandemic. In New York City during the fifteen years before 2020, over 20 percent of nightlife businesses closed their doors due to rising real estate prices, zoning pressures, increasing operating costs, noise complaints, and gentrification.3 These barriers were and still are too much for small businesses to bear, especially when compounding these issues with today’s inflation and rising costs.

For cities, this places yet another strain to provide affordable housing, avoid gentrification, and support the economic development and the infrastructure needed to nurture thriving local artist communities. Our challenge now as planners is to do the critical work to redress the harm and ensure that history does not repeat itself. Nightlife activism can find a home in planning following the lead of folks who are activelyadvocating for solutions in economic policy like commercial rent stabilization, tactical urban design, and dedicated investments to create democratic and cooperativelyowned urban spaces that can thrive both day and night.

FIELDWORK 18 -

3Economic Impact Study of NYC Nightlife— MOME. (n.d.). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/mome/ nightlife/economic-impact-study.page

McCarren Park Pool before restoration into a vibrant community space.

Photo by Larry Racioppo

In March 2020, quarantine and social distancing were decreed in Havana, important in these times when COVID-19 threatens the health and life of all. From that moment, those who were lucky, were able to work from home. Homes turned into offices, schools, play spaces and beyond. Before Covid, the concept of the “home office” created enthusiasm and was desirable. We used to imagine that working from home would be productive because of the calm felt in one’s own home-the overwhelming silence and the feeling of autonomy provided by being able to decide what is worth your time, the lack of pressure from comparison to coworkers.

Protecting clubs, bars, and venues— particularly those owned by native residents and local communities of color—means preserving and stabilizing New York City’s cultural fabric. These efforts can also encourage public art and activism, creating a pathway towards civic engagement and deployed as an anti-gentrification strategy.

Since 2020, the improvement and progress has been undeniable. NYC’s nightlife has made a recovery, mostly due to grassroots activism, as well as real policy change from the Office of Nightlife (ONL) at the Mayor's Office of Media & Entertainment (MOME) leading to direct services, including direct services including mental health support for service workers and publishing quarterly transparency reports on Multi-Agency Response to Community Hotspots (MARCH).

Today, weeks into a nearly universal shift to working from home, for those who are able, the previous appeal of the home office is waning. Perhaps the discomfort comes from the over exhaustion of daily routines or because what was previously your “corner” - has become the place where you least want to be. Maybe it stems from family feuds, a lack of privacy, or the dissolution of tranquility, now drowned out by a continuous stream of distractions. Each minute feels as if everything is happening to you. You may have plenty of space or just the bare minimum: a place to get up from your chair, go to the bathroom (if no one is already waiting), to the kitchen (if there is space) , to stretch out on the sofa (when it’s not occupied), or to look out the window.

In July 2022, Mayor Adams suspended the city’s 25 percent surcharge businesses pay on state liquor licenses for a year, which will help businesses citywide save an estimated $6.5 million over the next year.

Across the country, the City of San Francisco has championed its Cultural Districts and Legacy Business programs—which both launched during the 2020 pandemic—as joint agency efforts to support community development, placemaking, and placekeeping. The Cultural Districts program’s vision is to preserve, strengthen and promote cultural communities, while the Legacy Business program focuses on supporting legacy businesses, nonprofits, community arts, and community-led traditions. Both programs aim to support specific cultural communities and ethnic groups that have been historically discriminated against, displaced, and oppressed.

19FIELDWORK

Photo by Mariah Chinchilla

Photo by Mariah Chinchilla

Globally, the movement is gaining momentum as well. The Global Nighttime Recovery Plan is a collaborative, practical guide for cities that are interested in developing safe and feasible strategies to reopen and reactivate their creative and night-time economies. The guide was published with the input of 130 practitioners, academics, public health experts, advocates, and service representatives from more than 70 cities all over the world, and is meant to be an interactive platform to share frameworks, tools, and practices among cities to map a new future for nightlife.

If spending time with your family is already somewhat awkward, it can be compounded by working from home. Tight quarters, shared resources, and lack of personal space can create conflict and discomfortseeing your mother running from here to there doing housework like an hormiga loca, your father watching TV and your brother playing and screaming. During times like these, perhaps your mother exclaims,

The solutions to our most complex urban dilemmas aren’t so far out of reach. As planners, we should follow in the footsteps of advocates by leaning into the sticky intersections of our work. Now is the time to take in everything, all at once, and see the bigger picture. Once we understand the value of community engagement and the generational expertise of those who have been systematically silenced is when we will begin to build a more equitable future for us all.

21MULTIPLICITY FIELDWORK

Photo by Mariah Chinchilla

Reclaim/Reuse/Recycle!

A CLINTON HILL HERITAGE DOCUMENTATION STUDIO

By Ethan Brown, Mahnoor Fatima, Tara Hopp, Megan Maize, Katherine Pioch, Diego Rivadeneira, Alison Weidman, Jeremy Ziegler

By Ethan Brown, Mahnoor Fatima, Tara Hopp, Megan Maize, Katherine Pioch, Diego Rivadeneira, Alison Weidman, Jeremy Ziegler

PR 839 Spring 2022 Studio

FIELDWORK

Chris Neville

Rebecca Krucoff

STUDIO MEMBERS

Ethan Brown

Mahnoor Fatima

Tara Hopp

Megan Maize

Katherine Pioch

Diego Rivandenra

Alison Weidman

Jeremy Ziegler

Welcome to Clinton Hill, Brooklyn! Or is it Fort Greene? Or Bedford-Stuyvesant? The Gold Coast?

The study area that we surveyed in January 2022 for our Spring Heritage Documentation Studio has been known by many different names over time, reflecting the flexible boundaries and diversity of functions and people we observed. Throughout the semester we kept coming back to a foundational question: what is this place?

The answer changes based on the respondent and lies somewhere between the historic buildings and the people here today. To answer the question, we surveyed examples of historic spaces that evolved to meet contemporary social purposes in and around the study area. What we found were fascinating stories of wealthy industrialists, working-class immigrants, working women, Vaudeville actors, artists, and community gardens.

Pratt Institute sits at the center of our study area, and for our project it was a way to name and define the neighborhood. The Pratt Area saw a second wave of growth and development in the late 19th and early 20th century with an upper-class corridor developing on Clinton Avenue in the North; in the rest of the study area, housing was built by local developers for middle- and working-class families in the 1870s.

23MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

FACULTY

As a wave of industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th century washed over the Pratt Area, a wellspring of new forms of transportation into and out of Brooklyn developed, including the Brooklyn Bridge (completed in 1883) and the Myrtle Avenue Elevated Line (which ran in 1888). In the decade that followed, the gradual departure or death of the once-large industrialist community—paired with a new wave of migration within and immigration to the United States spurred on by World War I and urbanization— resulted in a large demographic shift in the community.

In the 1950s–1960s, the area experienced another shift from being a majority-white community to one chiefly populated by poor and workingclass people of color. This “white flight,” catalyzed by post-war federal housing policies that

24MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

The Vaudeville Peerless Theatre declining in the 1960s. Source: CinemaTreasures

The Artist’s Studio, formerly a candy factory. Source: Jason Schmidt

Myrtle Ave Elevated Line Construction. Source: NY Transportation Museum (above)

Myrtle Ave Elevated Line Construction. Source: NY Transportation Museum (above)

both encouraged disinvestment in cities and white settlement in the suburbs, was used as a rationale for the demolition of swaths of neighborhoods for urban renewal projects.

By the 1960s and into the 1970s, political and social policies stimulated the deindustrialization and disinvestment that left the Pratt Area a stressed and fragmented version of its former self. The area was sustained and gradually mended with the continual efforts of neighborhood leaders, community-led block associations, and ambitious creatives, which helped orchestrate the area’s resurgence as the vibrant commercial corridor one experiences today. The Pratt Area today is a predominantly urban residential neighborhood hosting two colleges: Pratt Institute and St. Joseph’s University. The Myrtle Avenue commercial corridor lies

at the north with many businesses (art stores, galleries, bars, and restaurants) catering to residents and the Pratt student-base.

The buildings, like the people they serve, require reinvestment and care to evolve and survive. Whether adaptive reuse gives an abandoned structure a new life or reuses it for a new function based on economic and social changes, what is important is that the built fabric of the past continues to exist as a space where the life of the community can continue to unfold for many years to come.

Our methodology for this conclusion has come out of our inductive historical documentation process. It started by dividing up the larger study area into smaller sections and assessing individual sites for recurring patterns. However, moving into the demographics and archival work, we noticed

a changing pattern of people within the census data, and a continuous diversity of people from a wide range of ethnicities and social strata. Because these changes were so widespread and consistent in the data, we could assume that there were broader historical patterns to explain why certain communities and businesses settled in their respective locations.

We realized that we needed to zoom out and look at wider historical contexts and archival research. We looked at fire insurance maps, newspaper archives, and other historical documents to understand the primary forces of change. When that became too abstract and distant, our conversations with the stakeholders from the Myrtle Avenue Business Improvement District and the Myrtle Avenue Revitalization Project helped bring a lived experience to the

26MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

Methodology Visualization

story we were uncovering on maps. This process helped us uncover three kinds of largescale change: physical (the changes of the buildings), historical (connecting to the wider history of Brooklyn and New York) and social (the lived experience and culture of those who long lived in the area).

The term ‘adaptive reuse’ arose as a thread connecting the physical changes witnessed in the neighborhood to larger historical changes and the micro-social changes experienced by those in the neighborhood. Adaptive reuse was the most apt term to describe the historical developments in the area and works as a phrase commonly accepted in architectural practice and history to describe buildings that have changed in function or structure over time.

In How Buildings Learn, Steward Brand explains how all buildings on some level have to adapt to their external environments, contrary to the idea that a building is ‘fixed’ in space and time.1 The term ‘building,’ much like the term ‘adaptation,’ speaks to not only the verb and noun (that which is being built or adapted) but also the active

effort to build or adapt. Many see adaptive reuse as a positive force which prevents the wastage of existing buildings and counters any further environmental degradation that may occur when building a replacement. Adaptive reuse, however, has a dark side tied to the devastation that came with urban renewal and gentrification. Many have lost their homes, businesses, and communities due to these processes, and could not return to their homes due to high rents and

27MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

Fire Insurance Map of Pratt. Source: Tara Hopp

MULTIPLICITY

1940s Tax

Photo of Reinkin Dairy (above), Reinkin Dairy Building Today; credits: Jeremy Ziegler

mortgages. Our interpretation of adaptive reuse hinges on not only physical changes like remodeling or conversion, but also the way that relationships between spaces—and the people who use them—are changed due to changes in the larger area.2 Sociologist William H. Sewell explains that our built environment informs our social experience, thus as the environment changes, cultures and institutions change their practices over time.3 Heritage preservationists like Dolores Hayden also adopt such frameworks by emphasizing the need to consider all aspects of social histories before adapting and restoring buildings, because simple materiality cannot explain the context.4 Within the preservation field more specifically, adaptation is defined by the National Trust for Historic Preservation as: “the process of converting a building to a use other than that for which it was designed.”5 We are trying to expand beyond this

definition, and use adaptation as a radical tool. This type of adaptation is the spontaneous, user-led transformations of existing historical buildings that create shared meanings through use. It is these changes that inform our use of adaptive reuse and vision of it through a bottom-up perspective rather than the real estate and economically-driven one with which it is usually associated.

Our study focused on the narrative of buildings, their builders, occupants, and workers. The changes to the buildings are often unplanned and have greater repercussions than imagined by individuals. It was our responsibility to uncover as many changes as possible, and to give agency and justice to all community members involved in the production of the space. We highlighted the main eras of change that prompted new waves of adaptive reuse which we used to categorize the overlapping historic eras of Clinton Hill:

Urbanization (1801-1933), Industrialization (1901-1941), Urban Renewal (1935-1968), and Cultural Shifts (1920-2004).

We uncovered stories of pain, resilience, economic prosperity, and diversity that mirrored the wider urban history of New York and the United States as a whole. We also began with walking as a spatial pedagogy. Such embodied, bottom-up, and communitydriven spatial approaches have been spearheaded by the likes of Henri Lefebvre, Jane Jacobs, and Michel de Certeau. Through our compiled tour and Spotify playlist, we invite those interested to walk the Pratt Area and learn the stories that are hidden by changes and time. We hope to inspire anyone with an interest in their community to actively participate in its reinvention, imagine collaborative futures, and transform spaces to preserve them for the future rather than just demolish the past.

29MULTIPLICITY STUDIO 1. Brand, Stewart. How Buildings Learn. New York, NY: Penguin Publishing Group, 1995. 2. Brooker, Graeme, and Sally Stone. Rereadings: Interior Architecture and the Design Principles of Remodelling Existing Buildings. London, UK: RIBA Publishing, 2014. 3. Sewell, William H. Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005. 4. Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995. 5. Murtagh, William J. Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2006.

Thesis

Historic Preservation

THE IMPERMANENCE OF THE VODOU RELIGION IN THE HAITIAN DIASPORA

by Claude Jeffrey Charles-Pierre Spring 2022

If one were to ask a Haitian in East Flatbush, Brooklyn where is Gran Bwa located, they will tell you it’s in Prospect Park near the Parkside Avenue entrance. They may point you in the direction of the lake if they are near or in the park. If you were not familiar with what goes on at Gran Bwa, it would be hard to find this special and sacred place in the community. The meaning of Gran Bwa is large tree/wood and the spirit of trees.

Raised in a Protestant household, Haitian immigrant and artist Deenps Bazile moved to East Flatbush, Brooklyn in 1979. Deenps lives a short walking distance from Prospect Park near the Parkside Avenue entrance. In an interview, Deenps explains how the sounds of drums and a spirit guided him to Prospect Park near the south section of the lake to carve a sculpture from a large tree stump that was about four feet high and at least four feet wide. Deenps carved a large human head, two miniature human faces, a lion, and a Legba. A Legba is a Lwa (god) in Haitian Vodou.

The park’s natural elements, such as the lake and how the sun and wind reflect and move the trees, remind him of being in Haiti. This is how this site became known as “The Gran Bwa” site in Prospect Park. Haitians in the community began to congregate every weekend at Gran Bwa and still do to this day. Deenps became known as Neg Gran Bwa (Man of Big Tree). Deenps recalls the local Haitian Protestants against him carving the tree stump. While watching him carve the tree stump they began to chastise him for bringing evil to the Prospect Park area. Not too long after that, the sculpture was vandalized and destroyed by someone lighting it on fire. The remains of the carved tree stump eventually were chopped, adding to the destruction of the Legba sculpture. Today, there is only the outline remnant of the Gran Bwa sculpture, and no one knows the exact reason why it was destroyed. Some speculate that the neighbors did not like the weekly gatherings or did not want Vodou ceremonies at the park. Neg Gran Bwa says, “The sculpture was removed but the spirit of the Legba is still present.” Today there are three large stones purposely placed at the location of the original Gran Bwa woodcarving.

THESIS31MULTIPLICITY

Gran Bwa sculpture site at Prospect Park Photo: J. Charles-Pierre

One can argue that this act of vandalism affirms Vodou as part of the emergence of the “despised history” that Andrew Herscher conceptualizes in “Counter-Heritage and Violence.” Herscher writes about the tangible heritage of churches and mosques that were vandalized or destroyed by its counterpart for the erasure of that heritage which results in a counter heritage1.

The Vodou religion and its intangible practices are highly susceptible to being erased because of its non-physical presence and consequently being memorialized in either the built or natural environments. Traditional Vodou ceremonies are practiced based on memory and memorialized through oral histories mostly near a body of water or in the woods. The marginalized history and rituals

of Vodou in the environment have endured adversity for several centuries despite the counter heritage that it faced. If the tangible places of worship were removed (church, mosque, temple) from Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, their rituals would still exist. These spiritual religions are still practiced today because it is about the belief system that remains in existence. How can Vodou’s religious practices or ceremonies in non-traditional environments or spaces kept in memory be documented or archived? What is the role of preservation in capturing these moments?

My work aims to raise awareness of the counter heritage Vodou that Vodou continues to endure while embracing and documenting the cultural heritage traditions of Vodou that is ingrained in the daily life of the Haitian community.

1 Andrew Herscher, “Counter-Heritage and Violence”: Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism, Winter 2006, Vol. 3 No. 2(Winter 20006), pp 24-33 University of Minnesota Press

The concepts of co-production and hybridity can be used as a lens to investigate the cultural heritage of Vodou in the Haitian Diaspora in Brooklyn. They can build an understanding of heritage that collapses the here/ now and there/before between the (then) Bois Caïman ceremony in Haiti and the (now) celebration of it in Brooklyn and between the (there) Botanicas in Brooklyn and (before) temples in Benin West Africa. Co-production of Vodou ceremonies is simulated in an environment that is different from its origins, but the rituals remain in existence. The hybridity of Vodou in Haiti and Brooklyn stems from a cross between what and how it was practiced in the different regions of West Africa. ADAPTATIONS

CO-PRODUCTION

ACROSS TIME & SPACE

TRANSFORMATIONS

THESIS 33 -

Photos: Montrose-Louis; Caterina Cleric, The Guardian Photo: Kesler Pierre

Gran Bwa sculpture. Photo Courtesy of Deenps Bazile

The understanding of placed-based heritage elsewhere and its ethos of hybridity can be recognized by its necessary diversity and constructive impurity. Discovering that my Haitian ancestors derived from West Africa either from Benin, Togo, the Kongo, or Dahomey Kingdoms, led me to the realization that they all have the Vodou Religion in common. The distinct altars of worship, outfits of the dancers, the beating of drums, and singing during offerings, all are culturally co-produced in a built or natural environment. The constant adaptation, remaking, and transformation of the Vodou Religion from the past, present, and future is the makeup of its cultural-religious heritage.

Since 1992, a few Haitians, a few Haitians from the recently-designated Brooklyn community “Little Haiti” adjacent to Prospect Park, celebrate the Bois Caïman ceremony annually in August to commemorate the anniversary of the 1791 insurrection of the enslaved Africans in Haiti that catapulted the Haitian Revolution. This makeshift, outdoor cultural meeting space occurs at the Gran Bwa site. The wood sculpture that bore its name is no longer at the location, but the site is still used as a gathering place for the Haitian community to bond and experience the healing power of the Gran Bwa spirit associated with trees, plants, wind, and water.

The yearly celebration of the Bois Caïman ceremony at Prospect Park Lake in Brooklyn is in danger of being eliminated due to the lack of awareness of the general public, the migration of Haitians to the suburbs, the gentrification of the surrounding neighborhoods, and the proposed capital improvement of Prospect Park Lake by the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Preserving this makeshift, coproduced space is imperative imperative and underscores the importance of

viewing place-based heritage in a way that embraces hybridity and coproduction across time and space and that builds off the practice and ethos of Vodou. Religious practices or ceremonies that occur in non-traditional religious environments should not be excluded from Preservation. The practices and history of Vodou as part of the Haitian Diasporas culture is fundamentally relevantto the current conversations of equity and inclusion in the Historic Preservation space.

Reimagining Our Streets: What We Resisted, Adapted, and Reclaimed in Brooklyn

Prospect Heights Open Streets: Community Led, Community Driven

By Semire Bayatli and Walker Johnston UPM609 Lan Analysis of Public Space Spring 2022 Studio

An architectural project first emerges as a problem and a design opportunity. The project is a journey that can be done at many scales, from interior design to city design and planning. The problem and opportunity turn into an idea in the hands of the designer, then a project as a team works collectively, and eventually a real building, structure, or place with the coordination of many different disciplines. All of these stages are a process and these processes require planning. However, sometimes the project does not arrive on time, even if everything is planned. Given the complexity and challenges of humanity, disasters, pandemics, and wars that hurt different parts of the world cannot be planned, despite our best efforts to anticipate and prepare. In spite of these unplanned processes, humanity reveals its power to heal. It resists, stretches and rebuilds, and a new city experience emerges.

In 2020 our entire world shifted with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; our understanding of the environment, the places we live in, and our expectations from our homes have changed. Despite the devastating hardships, loss, and collective trauma, we discovered our capacity to pivot, and that we were open to more. We decided to breathe more, drive less. We came to value the importance of social connection in profound ways, and in turn, as a society we worked to reinvision communities that support a vibrant civic life. In New York City, as well as many other parts of the world, this resulted in a reimagining of perhaps the city’s most mundane public spaces—the streets.

The NYC Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Open Streets program emerged as a way to reimagine streets for all people.1 In April 2020 the initiative began to provide

economic relief for restaurants and businesses and give New Yorkers more open space to safely socialize. After over two years, we now have an idea of the economic impact it provided. The Streets for Recovery: The Economic Benefits of the NYC Open Streets, published by the DOT in October 2022, found that businesses and bars on Open Streets corridors were able to stay in business at a higher rate than across the rest of the same borough, and sales growth on Open Streets corridors significantly outpaced sales growth in the boroughs that the corridors are in.2

While recovery from COVID-19 is largely considered the impetus for this public reimagining of the function and capability of streets, the sentiment behind streets for the people extends beyond an emergency response to the pandemic; many people see Open Streets and other

36MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

Lida Aljabar

Emily Ahn Levy

STUDIO MEMBERS

Zein ali Ahmad

Semire Bayatli

Ziqing Feng

Clay Grable

Walker Johnston

Alexander Lipnik

Marium Naveed

Maithri Shankar

Robyn Stebner

Allie Wertheimer

Alexandre Zarookian

FACULTY

1. NYC DOT, “Open Streets.” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/ html/dot/html/pedestrians/openstreets.shtml 2. NYC DOT, “Streets for Recovery: The Economic Benefits of the NYC Open Streets Program,” October 2022. https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/ pdf/streets-for-recovery.pdf Conceptual map of the study area. Illustration by Zein

Ahmad.

ali

street repurposing initiatives as an important step in the fight against the climate crisis and traffic violence; in this sense, there are multiple crises calling for collective adaptation.

Streets that are closed to traffic and open to pedestrians are part of our new conception and reality of the built environment. The Urban Placemaking and Management (UPM) had the opportunity to study this new typology of public space in the Spring 2022 Studio, exploring the Vanderbilt and Underhill Open Streets in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn.

The Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council (PHNDC)—a 501(c) (3) and civic organization that advocates for neighborhood-wide issues on behalf of the residents and businesses of Prospect Heights and manager of the two Open Streets3—invited the UPM studio to help envision a sustainable, generative, longterm future for Vanderbilt and Underhill Avenues.

The Open Streets program is a true collective effort— management of the Vanderbilt and Underhill Open Streets is spearheaded by passionate community members volunteering their time, with operations and some financial

38MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

3. Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Corporation,“About PHNDC Phndc.Org.” Accessed January 27, 2022. https://phndc.org/content/about-phndc.

One-point perspective sketch of Vanderbilt Avenue by Zein ali Ahmad

support from the City. Early in the studio process it became clear the adaptation of city streets into places for people doesn’t come without its challenges: namely, streamlining daily operations and long-term management of public spaces, and ensuring underrepresented community voices are centered in these decisions. History and demographic research, field work and site analysis, and community engagement with multiple stakeholder groups supported these findings, and revealed new ones:

1. There has been a significant amount of displacement of Black residents in the last 20 years.

2. Prospect Heights is now home to a predominantly white, high-earning, highly educated population.

3. Everyone approached Open Streets differently: one person’s Open Street is another person’s “closed street.”

4. Current management and operations is unsustainable due to the reliance on volunteers.

5. Safety (physical, emotional, sense of belonging, psychological) is of concern to most users.

6. The community’s ambition for a democratic commons is disrupted by current management, funding, operations of the Open Streets, as well as street design & amenities.

7. There is a lack of communication regarding intention, mission, and values of the Prospect Heights Open Streets.

8. There is a lack of system-wide strategy and intention behind the Open Streets program as a city-wide initiative.

Sketches of Vanderbilt Avenue facades by Zein ali Ahmad

Sketches of Vanderbilt Avenue facades by Zein ali Ahmad

From these key themes in our findings, we developed seven guiding principles that form the foundation of our recommendations:

THE STREET SHOULD FACILITATE COMFORT AND BE USABLE WITHOUT CONCERN FOR SAFETY

THE STEWARDSHIP OF THE OPEN STREETS SHOULD BE COMMUNITY-LED AND PARTICIPATORY

THE MANAGEMENT, OPERATIONS, AND FUNDRAISING SHOULD ENABLE A SCALABLE AND SUSTAINABLE MODEL AND SHOULD HAVE AN EQUITABLE IMPACT

CLIMATE RESILIENCE GUIDELINES SHOULD BE INCORPORATED INTO STREET DESIGN, PROGRAMMING, AND COMMUNICATIONS

THE OPEN STREETS PROGRAM SHOULD BE INCLUSIVE OF THE NEEDS OF ALL USERS AND SHOULD HAVE AN EQUITABLE IMPACT

THE OPEN STREETS PROGRAM SHOULD HAVE ACCESSIBLE, TRANSPARENT, AND CONSISTENT MESSAGING AND COMMUNICATIONS

Because the client of the studio was the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council, our scope of work was narrowed to the neighborhood level, with our recommendations tailored to the Prospect Heights community. Thinking more holistically about the city-wide approach, the case of Vanderbilt and Underhill revealed a critical opportunity to make the program more equitable through better distribution of resources to Open Streets

across the city. We proposed the creation of full-time, paid Open Street Liaison positions through DOT. We imagined multiple Open Street Liaisons for every borough who would work with a number of community partners to: better engage the community; help measure impacts of the Open Streets through standardized evaluations; and help communicate planning, permitting, programming processes of the Open Streets program to local residents.

THE OPEN STREETS PROGRAM SHOULD PRESERVE THE HISTORY AND CULTURES OF THE NEIGHBORHOOD AND INCORPORATE ANTI-DISPLACEMANENT STRATEGIES

41MULTIPLICITY STUDIO

SCOPE OF RECOMMENDATIONS AND HIGHLIGHTS

Governance: Scalable, Equitable Distribution of Power

Mgmt & Operations: Paid roles; Diverse Involvement Opportunities

Fundraising: Envisioning a Long-Term, Sustainable Future

Communication: Accessible, Inclusive, Transparent, Consistent Street Design: Strategies for Connectivity, Safety, Sustainability, & Community Well-Being

Programming: Preserving Opportunities for Organic Informal Programming & Centering Community Agency

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Safety&ComfortCommunity-led& Participatory Cultural Preservation& Anti-Displacement Equity& Inclusion Sustainable& Scalable Model Climate Resilience Transparency& Consistency

Vanderbilt Avenue Open Street at Bergen Street intersection. Source: UPM Students

Even more broadly, the Open Streets program demonstrates the City’s continued interest in investing in public space. However, the City needs to make a more concrete investment in order for the program to be successful city-wide and not perpetuate inequities by requiring community partners to take on the majority of fundraising responsibilities and costs of running an Open Streets program. Furthermore, organizations like the Design Trust for Public Space4 and Open Plans5 have proposed policy changes at the city-wide level to create an agency dedicated

to public space. Based on our research and analysis, we support the creation of a new agency, inter-agency, or an office that sits within the Mayor’s Office dedicated to public space management to enable a longterm investment in all the Open Streets programs across the city.

Of course, the Open Streets program isn’t the first time people have been advocating to reimagine the street. Many organizations and community leaders have been advocating for streets for people and will continue to do so. Notable are the efforts by advocates to repurpose

the curbside lane, whose current primary use is car parking, to make for more sustainable, social, and safe streets. Admittedly there is a long way to go to transform streets into thriving, democratic public spaces. Yet, it’s critical to recognize the Open Streets program—and other imaginative uses of the street—as a tool for change to create more liveable communities. Perhaps the greatest success of the Open Streets program is its ability to awaken our collective capacity to imagine a city we want to live in and work to make it a reality.

43MULTIPLICITY STUDIO 1. NYC DOT, “Open Streets.” Accessed January 30, 2022. https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/ pedestrians/openstreets.shtml 2. NYC DOT, “Streets for Recovery: The Economic Benefits of the NYC Open Streets Program,” October 2022. https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/streets-for-recovery.pdf 3. Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Corporation,“About PHNDC Phndc.Org.” Accessed January 27, 2022. https://phndc.org/content/about-phndc. 4. Open Plans, “Public Space Management.” Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.openplans. org/opsm. 5. Murtagh, William J. Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2006..

Mock-up community outreach posters from PHNDC. Designed by Allie Wertheimer

Thesis

City and Regional Planning

CHALLENGES TO FRESH FOOD AVAILABILITY IN CONEY ISLAND AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR INCLUSIVE AND SUSTAINABLE LAND USE THROUGH COMMUNITY GARDENING

by Nana Acheampong

Spring 2022

Residents of Coney Island suffer from poor access to fresh, affordable, nutritious, and culturally appropriate foods. Coney Island reflects a community long affected by top-down planning structures, with lacking inclusion of the local community through resident-led actions over land use decision making. This issue of effective nourishment through fresh produce sourced locally is in conflict with the community’s agency over land use actions most beneficial to the long existing residents of the community and their future generations. While food sources exist, they provide limited access to affordable, nutritious, and culturally relevant options. Coney Island currently has a ratio of 1 supermarket to 21 bodegas.1 Gross abuses of inequitable land use development practices by the City of New York has had its unpleasant mark on the historical and present day development of Coney Island.

Early examples include the creation of poorly equipped bungalow structured housing communities in the west end section of the present day neighborhood,2 which housed immigrant groups such as Puerto Ricans and African Americans immigrating from the south, after they were denied access to rent apartments along Ocean Parkway.3

The West End of Coney Island is now predominant to low-income residents, and residents of color residing in NYCHA apartments. Much of the West End section of the community was redlined, designating Coney Island as “C” and “D” levels. The “C” classification designated such areas as yellow or in decline, while “D” defined in red recommended investors to stray away from investments in such areas.4

45THESIS MULTIPLICITY

NYC Department of Health. (2018). “Coney Island Brooklyn Community District 13.” www1.nyc.gov/ assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2018chp-bk13.pdf.

Weinstein, R. M. (2007). Succession and renewal in urban neighborhoods: The Case of Coney Island. Sociation Today. http://www.ncsociology.org/sociationtoday/v52/coney.htm 5(2).

Gerstein, Josh. 15 Feb. 2017 “FBI Releases Files on Trump Apartments’ Race Discrimination Probe in’70s.” Politico, www.politico.com/blogs/under-the-radar/2017/02/trump-fbi-files-discriminationcase-235067. 4. Hillier, A. E. (2003). Redlining and the homeowners’ loan corporation. Journal of Urban History, 29(4), 394-420.

1.

2.

3.

The government’s topdown review and decisionmaking processes, justified through Universal Land Use Review Procedure and City Environmental Quality Review, most recently supported outside real estate interests which led to the demolition of the Unity Street Towers Boardwalk Community Garden plots in 2013.5 The formerly thriving Boardwalk Community Garden, formerly located at West 22 Street, served over thirty resident gardeners who cultivated plots to grow food and produce medicinal plants, used as an alternative to holistically heal ailments and illnesses. The demolition forced a unified group of gardeners to renounce their ownership over the garden after years of their cultivation and maintenance of the plot. Today, it is now home to an Amphitheater and Childs Restaurant.

From observations through a community-centered gardening pilot program in 2021, in partnership with the Coney Island Anti-Violence Collaborative (CIAVC), my research examined opportunities for alternative land use practices to support a localized produce hub. CIAVC acknowledges the multitude of socio-environmental and socio-economic benefits a year round community gardening program can provide. Increased community centered gardening opportunities can serve as a holistic benefit tool to activate community ownership of existing and adaptable spaces in the community. The action of collective residentled gardening can support jobs and workforce development, community beautification, green infrastructure enhancement efforts, and climate change adaptation in this coastal community.

Community Gardens Before & After Demolition

MULTIPLICITY THESIS46 -

Boardwalk

Boardwalk Community Garden Bulldozed in 2013 by The City of New York, NYCCGC

5. NYCCGC Boardwalk Community Garden (2013) Bulldozed in by The City of New York

W. 22 Street Unity Towers Boardwalk Garden in Full Bloom, Rob Stephenson, 2012

Planning & Programming the CIAVC Gardening Pilot Program, Nana Acheampong, 2022

Planning & Programming the CIAVC Gardening Pilot Program, Nana Acheampong, 2022

Today the work continues by residents and local organizations aligned to mitigate high rates of poor nutrition and the lack of neighborhood resources to fulfill needs in Coney Island.

Regional and global emergencies such as Hurricane Sandy and the COVID-19 pandemic compelled this resilient community adapt to the unfortunate conditions, through community reliance on local organizations and local political offices to meet the emergency need of fresh and affordable local produce.

In the summer of 2021, CIAVC secured space with the existing Surfside Garden located on Surf Avenue, which was a temporary pilot program effort towards the future planning of a permanent space for resident cultivation of fresh produce. The gardne also functions as a safe community healing space from gun violence affecting the community. The pilot program provided a lens into the opportunities and challenges in scaling up existing gardens, such as successful land use allocation in the community.