A Handbook for Protecting and Restoring Teton County’s Vital Water Resources

A Handbook for Protecting and Restoring Teton County’s Vital Water Resources

Here, at the beginning of the Snake River, water flows clear and wild, sustaining life across an entire ecosystem.

But that gift isn’t guaranteed, and it comes with great responsibility.

Our actions—large and small—shape the health of our streams, rivers, and aquifer. Every decision we make also flows downstream, touching lives we’ve never met.

This guide is your invitation to become a steward of the waters that sustain the health of our community, our wildlife, our economy, and our future.

Clean water starts here – with us.

Teton County, Wyoming is at a crossroads. Growth in population, tourism, and development is putting increasing pressure on our water. The health of our watershed—and the people, ecosystems, and economy it supports—depends on how we respond. Thankfully, our community is rising to the challenge of undoing the damage.

In 2020, Protect Our Water Jackson Hole (POWJH) worked closely with Teton County to build a comprehensive Water Quality Management Plan (WQMP). A roadmap to guide decisionmakers, the WQMP addresses management of wastewater, stormwater, and drinking water to restore and protect our community’s water resources. But plans alone won’t protect our water – it will take action from all of us to ensure a future with clean water. As a headwaters community, Jackson Hole can become a shining example of forward-thinking water quality solutions.

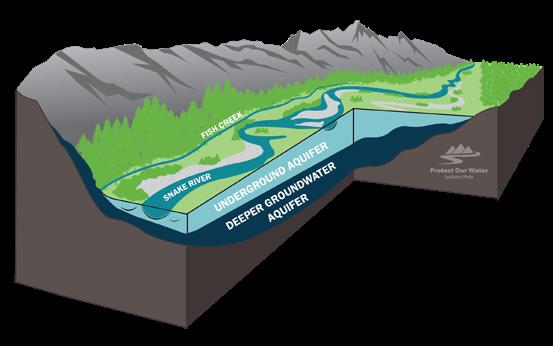

Teton County lies at the headwaters of the Snake River, which begins in the high, remote wilderness of Yellowstone National Park and flows over 1,000 miles to the Columbia River and Pacific Ocean. The Snake River is the lifeblood of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the last nearly intact ecosystems left on Earth. The Snake River Headwaters watershed stretches from southern Yellowstone to the Snake’s confluence with the Hoback River.

Understanding our Watershed

Snowpack is our primary water source. Snowmelt recharges rivers, wetlands, and aquifers in spring and early summer. When water runs across roads, lawns, or pastures, it can pick up pollutants like nutrients, bacteria, and other contaminants that threaten water quality. This runoff doesn’t just flow into streams—it can seep underground into our drinking water. Teton County comprises the majority of the Source Area for the Eastern Snake River Plain Sole Source Aquifer. Not only do 99% of County residents rely on our aquifer for drinking water, but the groundwater flowing through our community also supports drinking water and irrigation supplies for thousands of downstream Idahoans.

Most of the water in the Snake River is not in the visible river channel. Beneath our feet, water moves unseen through the gravel and cobble across the valley floor in an ‘invisible river’. Interaction between surface waters and groundwater is fundamental to the health of gravel-bed river ecosystems. Due to the high connectivity between surface waters and groundwater, this aquifer is highly vulnerable to contamination. Everything we do on land affects this critical water supply.

Today, while only 3% of the county is privately owned, much of that land sits directly on the floodplain—the core of our ecosystem’s biodiversity. This habitat nourishes an entire food chain from microbes and aquatic insects, to grizzly bears and humans.

Healthy rivers, clean drinking water, and thriving wildlife all depend on an intact, functioning watershed. When we see our watershed as an interconnected system, we understand the importance of making the best decisions to protect our water quality.

powjh.org/snakeriver

pre-existing watershed, digging many miles of irrigation ditches, introducing livestock, and developing the towns and neighborhoods we now inhabit.

Now, even in a place as wild and beautiful as Teton County, water quality from the snowy peaks to the underground aquifer, is under growing stress. As more people live, visit, and build here, increased pollutants from our everyday lives are showing up in our streams, rivers, and drinking water.

For decades, the abundance of snowmelt, surface water, and groundwater could absorb and dilute almost any contamination of water resources from a relatively small population. But as our communities grow and the climate changes, we must face our prevalent water-contamination realities

Groundwater and surface waters are connected.

Our surface waters are only the visible components of a deep aquifer running almost edge-to-edge through our valley. Due to this intrinsic connection, contamination from the surface can spread easily to groundwater.

Several localities are already dealing with the impacts of contaminated drinking water. Nitrates and bacteria are the two most common drinking water contaminants, but many others exist.

Our two most important creeks, Flat Creek and Fish Creek, are officially “impaired”—polluted to the point that it cannot fulfill its designated use—due to increasing sediments and growing loads of bacteria, nitrates, phosphorus, and other nutrients. These pollutants come primarily from fertilizers, septic systems, pet and livestock waste, and stormwater runoff.

Other contaminants, more recently identified, such as PFAS, have been introduced to our valley and the watershed, requiring decisive action to inhibit their presence and effects.

powjh.org/issues

In Teton County, almost everyone drinks groundwater. Beneath our valley lies the Eastern Snake River Plain Sole Source Aquifer, designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) because it provides 99% of our drinking water to residents, including those on municipal water supplies, such as in the Town of Jackson. Protecting this resource is critical.

flows across the land today can show up in your tap tomorrow.

Our shallow, rocky soils allow pollutants like nitrogen, phosphorus, bacteria, herbicides, pesticides, and harmful chemicals to easily move into our water supply.

of drinking water comes from beneath our valley, the Eastern Snake River Plain Sole Source Aquifer 99%

By law, these systems serve at least 25 people for 60 days or more per year. If you live in the Town of Jackson or are served by another PWS, it is required for PWS operators to perform regular water quality testing to ensure a safe water supply and to satisfy current state and federal regulations. This information must be provided to residents each year in a Consumer Confidence Report (CCR). This annual water quality report tells you what’s in your water and provides transparency on contaminants, treatment, and conservation.

Wyoming is the only state where the EPA, not the state, regulates PWSs. Therefore, the EPA is responsible for implementing some regulatory portions of the Safe Drinking Water Act. Increasing demand, aging infrastructure, and limited local oversight are among the challenges we face with some of these systems.

Homeowners using water from a private well or spring are solely responsible for its testing, operation, and maintenance. If you rely on a private well or spring, you are your own water manager. There is no routine testing unless you do it, and many contaminants have no taste or smell.

Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the EPA recommend testing at least annually. knowyourwell.org | epa.gov

There is never a bad time to test your well.

Spring and summer are good because snowmelt and rain are seeping into the groundwater, increasing the likelihood of contamination from the surface.

Winter is good because groundwater flows are at their annual minimum, which has the potential to minimize dilution and increase the concentration of contaminants.

You’re pregnant, nursing, or have children in the household.

You notice a change in water taste, color, odor, or clarity.

You experience unexplained illnesses in your household.

Your (or a neighbor’s) septic system fails.

powjh.org/well-testing

There was a chemical/ oil spill nearby, a flood, a land disturbance, or a fire.

There is water accumulating around your wellhead.

You drilled a new well or are buying or selling a property.

Avoid using or storing chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, vehicles/fuels, and other pollutants within 100 feet of your well.

Inspect the wellhead and casing for leaks, cracks, or damage at least annually. Ensure a sealed, intact well cap and that the visible casing is not corroded or damaged to prevent debris, contaminants, and animals from entering.

Maintain records of well maintenance, water quality testing, and any repairs.

Use berms or other physical barriers to prevent runoff from pooling around the well.

Maintain your septic system to ensure it is working correctly. Effluent from leach fields can contaminate wells.

Do not keep livestock near your well.

Install a barrier surrounding the well if wildlife frequents the area.

Ensure abandoned or flowing wells are properly plugged to prevent contamination.

• Teton County Health Department has $20 bacteria tests. Contact: 307.733.6401, tetoncountywy.gov/1079/water-lab

• Teton Conservation District has $50 chemical and bacteria test kits that include: arsenic, chloride, fluoride, nitrate, nitrite, pH, sodium, sulfate, total coliforms (bacteria), total dissolved solids, total hardness, and lead. Other metals can be added for an additional fee. Purchase online tetonconservation.org/well-test-kits

Elevated concentrations of nitrates in our drinking water are one of the strongest indicator of human contamination. The Teton Conservation District Drinking Water Quality Mapping Project (tetonconservation.org/drinkingwater-quality-mapping) found elevated nitrates in parts of Hog Island, Snake River trailer park, parts of Kelly, Pub Place, which is directly above Melody Ranch homes, Old West Cabins in South Park, and Alta. Groundwater in some areas of Hoback Junction already exceeds the EPA’s maximum allowable nitrate concentration.

The EPA’s current standard for maximum contaminant level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams per liter (mg/L), or parts per million (ppm), which was set in 1962 to protect against infant methemoglobinemia (Blue-baby syndrome). Other health effects were not considered.

Recent studies have shown increased risks of colon, kidney, and stomach cancer among people with higher ingestion of nitrate in water, and adverse reproductive outcomes including low birth weight, preterm birth, or central nervous system defects in infants.

POWJH considers drinking water with greater than 2 mg/L nitrate to be impacted by human activity and advises that water at or above this level should not be consumed.

LEARN MORE: powjh.org/health-advisory

What should I do if my drinking water well test results show nitrates at 2 mg/L or higher?

• Call the Teton County Health Department: 307-733-6401

• Call Teton County Public Works: 307-733-3317

• Purchase filtered bottled drinking water or install a filtration system that is designed to remove nitrates.

Coliform bacteria are microbes found in the digestive systems of humans and animals. E coli are a subset of coliform bacteria, are primarily found in feces of warm-blooded animals, and can indicate broader microbial problems in water.

• A water sample positive for Total Coliforms indicates it is likely that harmful viruses, bacteria, and parasites may also be present in the water.

• A positive result for E. coli indicates that the water source has possibly been exposed to human wastewater, animal feces, or surface water, and an imminent health risk may exist. E. coli is used as an indicator for fecal contamination. While many strains are harmless, some are pathogenic and can cause serious symptoms in humans such as mild to severe upset stomach, diarrhea, fever, and vomiting.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals found in products like cookware, rain gear, cosmetics, some ski wax, and fire-fighting foam.

Referred to as “forever chemicals”, PFAS don’t break down and can accumulate in the environment –and in people.

In addition to the broad dispersion of PFAS from this wide array of sources, a known PFAS groundwater plume in Teton County is migrating downgradient from the Jackson Hole Airport toward residential wells and the Snake River. The airport has been diligent in addressing the problem. They continue to test both on- and off-airport drinking water wells and provide whole-house filtration systems for any drinking water well located within the Airport’s Eligibility Boundary Area.

• Check if your home is on or near the Jackson Hole Airport PFAS plume.

• Choose PFOA/PFAS-free products when possible.

• Limit use of stain- or water-resistant sprays.

• Support policies to phase out PFAS use and invest in water testing and treatment.

• Stay informed and support local monitoring and cleanup efforts.

jacksonholeairport.com/community/waterquality ewg.org/pfas-resources

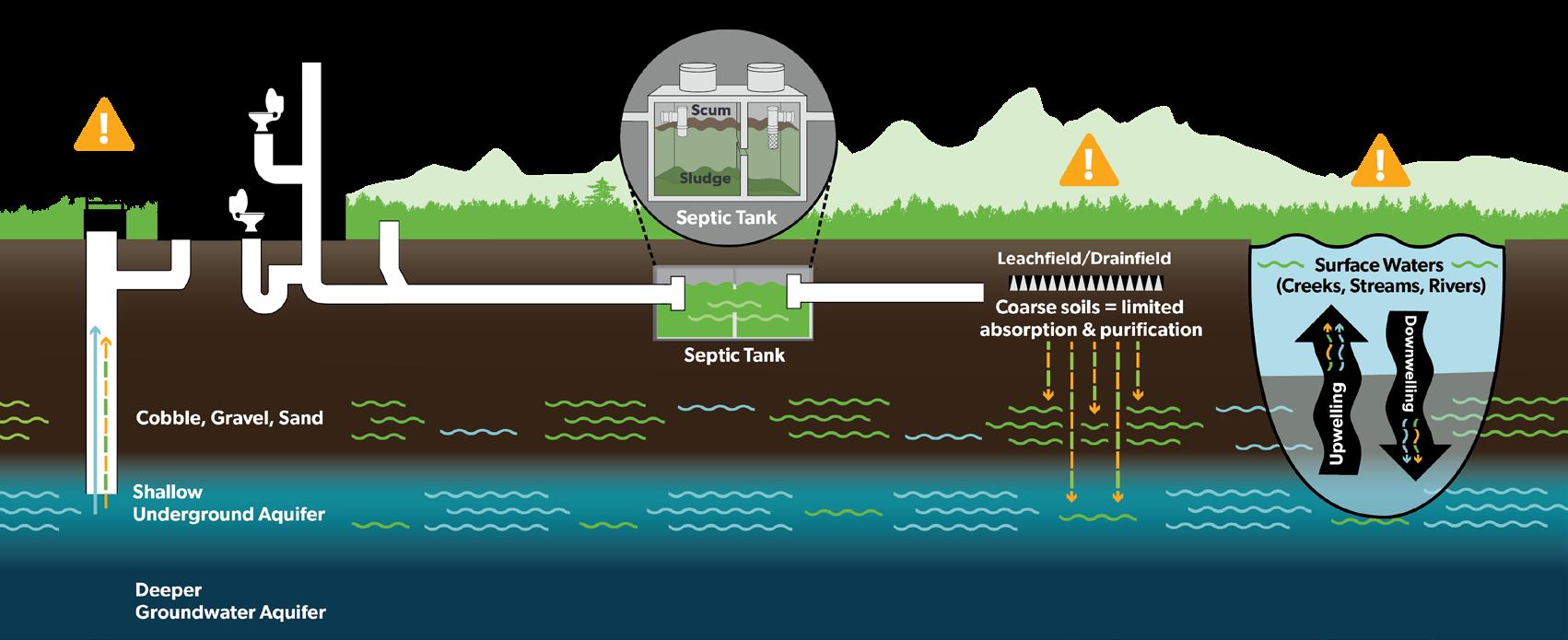

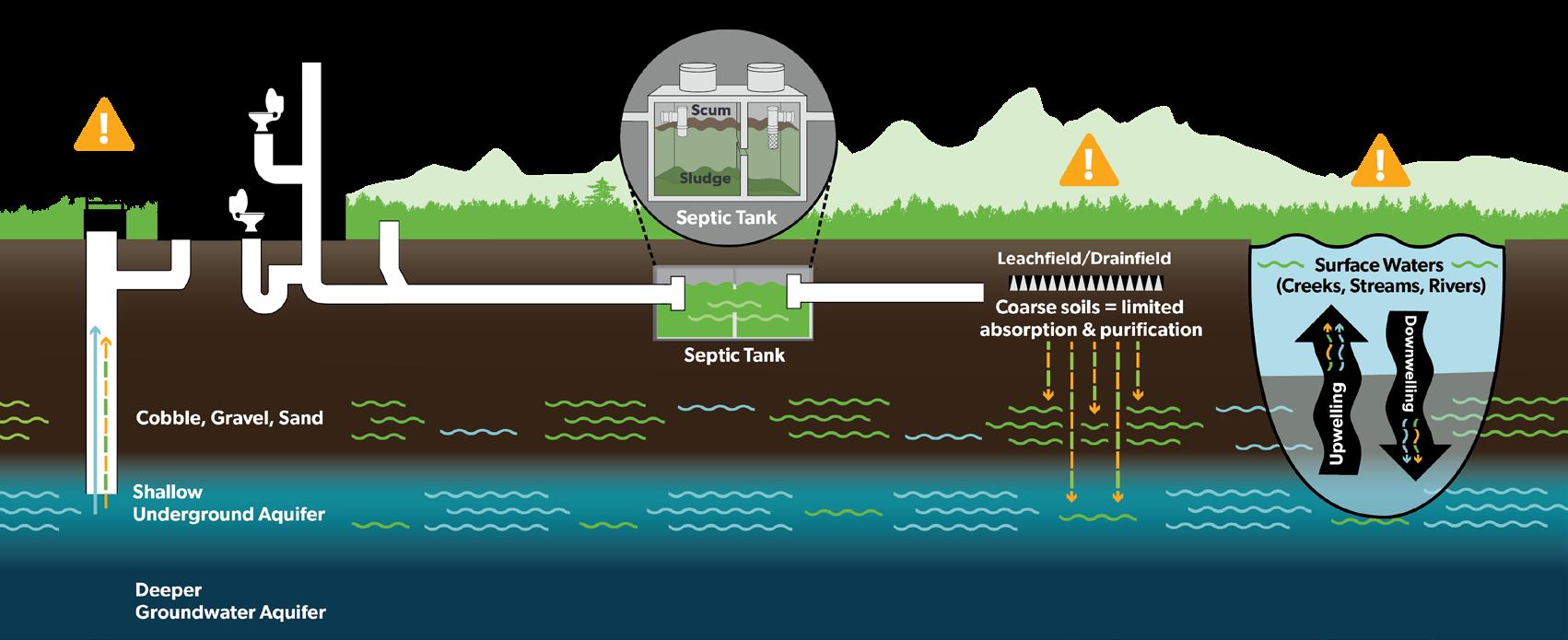

Wastewater is “used water” from sinks, toilets, showers, laundry, and more. Once it goes down the drain, it doesn’t disappear. It either gets treated at a centralized facility or flows underground through a septic system. In both cases, the quality of that treatment matters for the health of everyone and the watershed.

Wastewater is a primary source of nutrient pollution in our watershed—especially nitrogen and phosphorus, which feed harmful algal blooms and can contaminate drinking water. In Hoback Junction, a Wyoming DEQ investigation determined that the density of septic systems in the area has caused nitrate levels above the EPA’s safe drinking water limit, and elevated levels have also been found in areas across the county.

See Drinking Water on page 6

Protecting

water starts with smart choices at home. Every flush, drain, and load of laundry matters.

If your home is connected to a sewer system, your wastewater is collected and treated at a centralized location like the Town of Jackson’s treatment plant.

The Westbank of the Snake River also has three sewer districts including: Wilson Sewer District, Aspens Pines Water & Sewer District, and Teton Village Water & Sewer District. Homes in reasonable proximity to a sewer line should be connected.

The Town of Jackson’s treatment plant, constructed between 1978-81, and upgraded in the

• If your property is near a sewer line, connect to it. It’s one of the most meaningful things you can do for water quality.

mid-1990s, wasn’t designed for today’s population or pollution levels. In winter, it struggles to remove ammonia and phosphorus. However, centralized treatment— even when treatment plants are old and less technically sophisticated— still works better than aging or inadequate septic systems. Currently, Teton County underutilizes its wastewater treatment infrastructure. Some of the Westbank treatment facilities have adequate capacity to serve more homes.

• Support efforts to upgrade the Town’s treatment plant to a system that works optimally year-round and allows for water reuse.

If your home has a Small Wastewater Facility (septic system), wastewater is treated on-site in a septic tank and then discharged into the soil through a leach field. However, not all areas in Teton County are ideal locations for septic systems because of high seasonal groundwater levels, coarse soils lacking organic matter (sand, gravel and cobble), and cold temperatures, all of which have the potential to negatively impact systems relying on microbial activity in the tank and the leach field’s soil to treat waste.

Nevertheless, there are more than 3,000 septic systems in use across the county. Many are aging, outdated, poorly maintained, or over capacity. Even with regular inspections and maintenance, the average lifespan of a septic system is 20 to 30 years.

Many systems in Teton County have reached or exceeded their

• Speak with Teton County Public Works staff and your engineer/ contractor about site specifics to ensure you have the proper system for your needs.

• Have your your system inspected annually to determine if it is operating correctly, and have the solids pumped when indicated, generally every 3-5 years (and within 2 years to establish a baseline if it’s a new system).

• Don’t allow a tank to be cleaned through the inspection pipe. Ensure that baffles, effluent screens, pumps, and other components are inspected when the tank is pumped.

• Avoid using chemical-based tank additives.

• Take action to address potential problems rather than ignoring alarms or other warning signs.

• Support the implementation of improved septic system regulations in Teton County requiring regular maintenance and inspections.

A septic system works best when it’s the right size for the home and used consistently. The capacity of a household septic system is based on the number of bedrooms. When the system is properly sized, it provides necessary microbes with the right conditions to break down waste efficiently.

In Teton County, two common issues can throw this balance off:

If more people use the home than the system was designed for, too much wastewater enters the system, causing waste to be pushed through before it’s properly treated.

If fewer people use the home than expected, the septic tank’s beneficial microbes starve, weakening the system’s ability to break down waste.

In homes only used part of the year, the microbial community may die off during long periods of inactivity.

Seasonal underuse, followed by the introduction of large groups, can overwhelm the system, as the reduced microbial populations cannot break down the sudden increase in wastewater.

Wastewater systems rely on healthy bacteria to break down waste. Introducing other refuse or chemicals interferes with this process and limits the system’s functionality.

Only human waste and toilet paper should go down the toilet drain.

Use water-efficient appliances to reduce the volume of wastewater produced by your household and ease the strain on treatment systems.

Use biodegradable, phosphate-free cleaning products. Filter, capture, and compost food waste to eliminate use of the garbage disposal. Food waste can be composted through Teton County’s Integrated Solid Waste and Recycling program.

Never put the following items down your sink, toilet, or drain: so-called “flushable” wipes

oils/fats/grease

pharmaceuticals

feminine hygiene products pesticides/fungicides/ herbicides/algicides

paper towels

coffee grounds diapers

cat litter

chemical-based drain openers

hot tub treatments solvents or other household chemicals

any type of paints tetoncountywy.gov/2270/ Food-Waste-Composting

Stormwater is rain or snowmelt that flows over hard surfaces, such as roads, parking lots, buildings, driveways, patios, lawns, and pastures where soil is compacted or has shallow roots — increasing runoff and reducing natural infiltration.

It can pick up pollutants from impervious surfaces, landscaping, livestock grazing and corral runoff, snow storage, and pet waste. Eventually, these contaminants flow into storm drains, creeks, rivers, and lakes.

What You Can Do

• Reduce hard surfaces.

• Use Trout Friendly Lawn practices.

See Landscaping on page 19

• Always pick up and dispose of pet waste in the trash.

• Keep livestock away from creeks to reduce erosion and nutrient pollution.

• Support wetland restoration efforts help slow and filter stormwater and recharge groundwater.

One dog’s waste may seem insignificant, but it’s estimated that 11,000 dogs in the county leave over 8,000 pounds of poop per day.

Always pick up pet waste and dispose of it in the trash—every time, everywhere, even far from water. Dog waste is one of the primary sources of excess nutrients and E. coli fecal bacteria contamination through snowmelt and stormwater runoff.

Unlike wildlife, pets eat nutrient-dense food, and their waste introduces excess nutrients and microbial contaminants that can harm our watershed.

Cattle and horses are an indelible and cherished part of Western culture in Jackson Hole. However, they are also a source of pollution.

• Erect fencing to keep livestock away from streams and creeks. This reduces the introduction of nitrates and bacteria from manure and also helps prevent erosion of waterways and sedimentation into our waters.

• Use alternative methods of watering livestock besides letting them into streams and creeks.

• Restore riparian areas (shoreline vegetation) to limit runoff from grazing areas and corrals, and buffers waterways from contamination from manure.

powjh.org/nutrientpollution

Fertilizing lawns, ornamental plants, and trees is one of our most polluting behaviors. Nutrient runoff into streams from fertilization can cause eutrophication, the process of excessive nutrients in a body of water, causing dense plant growth that reduces oxygen levels for fish and other aquatic species. It also introduces excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into our drinking water supply.

Use Trout Friendly Lawn practices

• Limit fertilization: Use only slow-release or organic fertilizer only if needed, not to exceed two pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 sq. ft. of lawn per year. Do not fertilize within 20 feet of any water body.

• Eliminate or reduce maintained lawn areas. Replace maintained turf with meadow areas of native grasses. Native plants often require no fertilization or watering.

• Do not overwater. Water your lawn at dawn and dusk every other day, and don’t water while it’s raining. Raise your mower blade height to 3-4 inches so less water and fertilizer are needed.

• Plant natives and maintain a minimum 5-foot streamside buffer of unmanicured landscaping around water to act as a natural filter between lawns and waterbodies.

• Use herbicides and pesticides appropriately. Only apply herbicides to noxious weeds, using spot spraying or mechanical removal methods wherever possible.

• Support implementing regulations concerning lawn, plant, and tree fertilization in Teton County.

Join the Trout Friendly Lawns pledge: tetonconservation.org/trout-friendly-lawns

A riparian area is a vegetated zone along a body of water, such as a stream, river, pond, or wetland, and is crucial for managing stormwater runoff. As stormwater passes through a riparian zone, the vegetation and soil filter out pollutants before they can reach the waterway. This process removes nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, bacteria and pathogens, chemicals, and sediment. Deep-rooted native trees, shrubs, and grasses stabilize banks, reduce erosion and flood impacts, and provide shade that keeps streams cool for trout and aquatic life.

Native trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses have evolved to thrive in our local conditions. Once established, they need less water and fertilizer, providing low-maintenance, sustainable landscaping that supports our ecosystem.

Turf grass, however, is a poor substitute. Its shallow roots and frequent maintenance allow fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, sediment, and chemicals to wash directly into waterways.

• Keep existing native plants, shrubs, and trees — especially near waterbodies.

• Ideally, leave a 20-foot unmanicured, unfertilized buffer of native plants along waterways.

• Convert your lawn or nonnative species to droughttolerant native plants.

tetonconservation.org/ native-plants

Our connection to rivers and streams is one of the joys of life in Teton County but it also comes with responsibility. Whether fishing, swimming, floating, paddling, or hiking near water, there are several important things to keep in mind to protect your health and our ecosystem’s.

Fly fishing is an important part of our community’s identity. However, catch-and-release fishing is harmful if not done carefully. From hook set to release, it inherently exerts some level of injury and stress on fish. To minimize harm while fishing, please adhere to the following “Keep Fish Wet” principles.

Warm water is another major stressor. During the hottest months of the year, Wyoming Game and Fish will occasionally issue closures or advisories to protect fish from lethal stress. When water is warm (above 68°F), consider not fishing.

wgfd.wyo.gov/Fishing-andBoating/Fishing-in-the-heat

KEEP FISH WET PRINCIPLES

keepfishwet.org/principles

Minimize air exposure — keep fish submerged as much as possible. Eliminate contact with dry surfaces — wet your hands and landing nets. Reduce handling time — use barbless hooks and release fish quickly.

Waterborne pathogens like bacteria, viruses, and parasites become more concentrated during runoff season or after storms, and can make you sick. Avoid drinking untreated water, rinse off with clean water after swimming, wash your hands, and dry your ears thoroughly.

Nutrient pollution from wastewater, fertilizers, animal waste, and stormwater fuels algal blooms in creeks, and even the Snake River.

Blooms can smother aquatic habitats and reduce oxygen levels that fish and aquatic species need to survive.

Some blooms produce toxins harmful to people, pets, and wildlife. Toxic blooms can occur in both lakes and rivers. Fortunately, blooms in Fish Creek and the Snake River have thus far been non-toxic. However, toxic blooms are becoming increasingly common in our region, including Henry’s Lake, Palisades Reservoir, and several lakes atop Togwotee Pass. There is no way to tell if toxins are present without testing. Toxic algae blooms can cause serious liver, digestive, or neurological problems –and can be fatal to pets, livestock, and wildlife. If you notice foul odors, discolored water, or dead wildlife, avoid contact.

• Don’t let pets or livestock drink from or swim in discolored or slimy water.

• Learn to identify harmful cyanobacteria algal blooms – they can appear bright green, blue, paint-like at the surface, or like grass clippings.

• Sign up for Harmful Algal Bloom and Toxin Advisories in Wyoming and report potential blooms at: wyohcbs.org

powjh.org/algalblooms

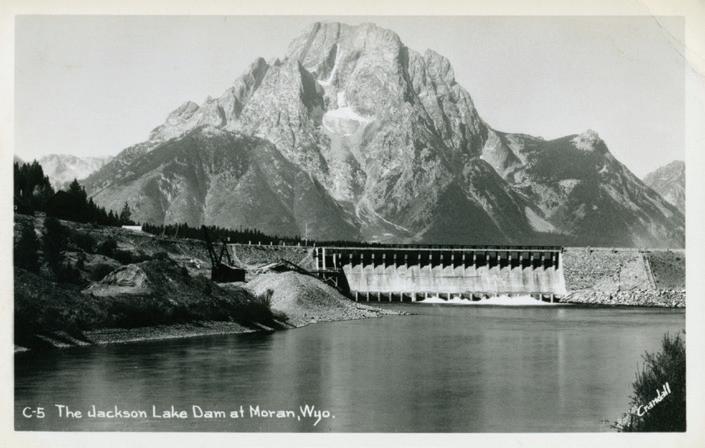

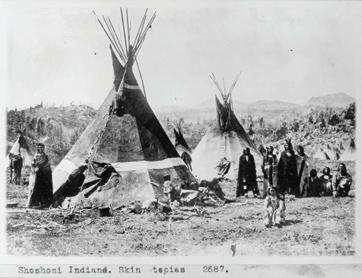

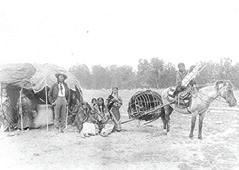

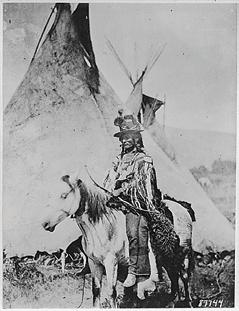

Source: waterarchives.org

Archaeological digs in various Jackson Hole sites have shown that humans have inhabited the Snake River headwaters for at least 10,000 years. Human habitation has been nearly constant since then, as thousands of indigenous generations have lived in balance with this land and taken advantage of the rich resources—big game, fish, edible plants, and copious water— we are still fortunate to enjoy, for now, but things are shifting.

American settlers brought dramatic change to the landscape. The manipulation of water was critical to settling the valley we now call home. Wetlands were drained for pasture, beavers were harvested for the fur trade, and rivers were dammed. The Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), established in the early 20th century to manage the nation’s water resources, was the driving force behind the construction of dams and the diversion of surface waters for irrigation. The Snake River Compact (1949) allowed Wyoming to store or divert just 4% of the Snake River’s

Over 400 miles of our waterways are designated as Wild and Scenic Rivers. It’s up to us to protect them.

flow to the state line. This means that 96% of the water flowing through our watershed is allocated to senior water rights’ holders downstream in Idaho.

Today, water is still managed by federal, state, and local governments. The BOR continues to manage flows out of Jackson Lake Dam. In Wyoming, the State Engineer’s Office is responsible for administering water rights. From establishing and enforcing water quality rules to setting standards for wastewater discharges, the Department of Environmental Quality oversees water quality throughout the state. Because Wyoming has not requested primacy to implement the Safe Drinking

Water quality is declining. But we can choose a different path.

Water Act (we’re the only state in the nation), this Act is implemented by the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 8 staff out of Denver. Finally, in Teton County, our Land Development Regulations and Small Wastewater Facility regulations are in place to protect water quality.

Despite past impacts, Teton County has a proud conservation legacy: Yellowstone was the world’s first national park, and over 400 miles of our waterways are designated as Wild and Scenic Rivers. Yet challenges remain. Water quality is declining. Development continues. We’re facing death by a thousand cuts—but we can choose a different path.

We respectfully acknowledge that we now inhabit a landscape once occupied by numerous Indigenous peoples such as the Shoshone, Kiowa, Lakota, Cheyenne, Bannock, Nez Perce, Crow, Blackfeet, and Gros Ventre, and many others whose names are lost to prehistory. These tribes have stewarded this land for thousands of years. May our actions honor their legacy by protecting this land and its waters.

Protect Our Water Jackson Hole (POWJH) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is to serve as a powerful advocate and catalyst for protecting and restoring the surface waters and groundwater in Teton County, Wyoming.

Clean water now and for future generations.

Science and Law-Based

Our work is based on sound science and legal principles.

Our only priority is to protect and restore water quality in Teton County.

Advocacy

We fight for clean water.

We are effective and resultfocused, knowing that we must all work together to ensure clean water.

We stay up to date on current research and offer innovative solutions.

Our hope is that this guide provides a snapshot and a clearer understanding of the issues we’re facing. Taking action is the next step—here are a few things you can do right now to help move us all toward a healthier Jackson Hole.

If you use drinking water from a private well or spring, test your well at least once a year.

Only flush human waste and toilet paper down the toilet drain.

Filter, capture, and compost food waste to eliminate the use of a garbage disposal.

Have your septic system inspected annually to determine if it is operating correctly, and have the solids pumped when indicated.

Always pick up and dispose of pet waste in the trash.

Limit fertilization and use slow-release organic fertilizer only if needed.

Replace maintained turf with meadow areas of native grasses.

Maintain a buffer of unmanicured landscaping next to water.

If your property is near a sewer line, connect to it.

Support clean water initiatives in our local and state government.

Scan the QR code to donate today or visit powjh.org/donate