Chapter 6 Village Life and Village People

The growth and development of a village like Potterspury, over many hundreds (or even thousands) of years, is mainly due to the people who lived here. We know very little of most of them. They were born, lived and died here, leaving little, if anything, to tell of their existence. Church records tell us of their baptisms, marriages and burials, and, in more recent years, photographs give us clues as to the way they dressed and looked. Some old dwellings still exist, but they give us little idea of the cramped and uncomfortable conditions in which the majority of poor people lived and brought up large families. Towards the latter part of the 19th century, Potterspury was a most unhealthy place in which to live, with serious outbreaks of enteric or typhoid fever, a situation not fully remedied until piped water was installed in the village some years later.

Few written accounts exist of Potterspury village life before the 20th century. However, some people found that living here was much to their liking, as suggested by part of a letter written by the Rev. George Vowell in 1794. He wrote, “I am quite happy in the expectation of an abode in Potterspury, where I can hear the rustling of trees, where I can listen to the nightingale’s melodious notes, and where I can enjoy a walk in the green fields.” (More of this is in the account of the chapel.) More recently, C.G. Harper, writing in 1902, described the village as “Wholly old world and delightful,” and continued, “One comes into it under the thickly interlacing branches of tall hedgerow elms that conspire to cheer the traveller with a perpetual triumphant arch of welcome. Through this leafy bower one perceives the roadside cottages dwindling away in perspective along a gentle rise.”

We are pleased to publish in this chapter a number of written and narrated memories of villagers, many of them of childhood days, spanning much of the 20th century and giving us graphic accounts of very different lives from those we lead today. We conclude the chapter with extracts of interviews which reveal changes in the routine daily lives of families, from the thirties to the present.

Our first collection of memories was written in the late 1950s by Miss Hilda Faux. In addition to some of the pictures that accompanied her manuscript, we are very fortunate, thanks to Mrs Mary Nunnari, in having access to many other photographs taken by her father, Mr E.F. Peasland, and we have included many of these in this book. The original manuscript is now in the possession of the Russell family who have kindly allowed us to include most of her ‘Memories’ in this book, together with many of the photographs it contains.

Memories of a Villager –from the early 20th century Hilda Faux

My memories of this village of Potterspury in which I was born, go back for nearly half a century, and my earliest recollections are centred around St Nicholas Church and Wakefield Lodge, at that time the home of the seventh Duke of Grafton.

85

Watling Street in the early years of the 20th century.

Hilda Elizabeth Faux

Hilda Elizabeth Faux was born in Potterspury on St Valentine’s Day in 1906, the daughter of Benjamin, a carpenter, and Mary Faux. After leaving school she trained as a teacher and taught for many years at Wolverton where her pupils remembered her as firm but gentle, much loved and admired. Hilda was a regular church-goer and helped with the Sunday school. She also took an active part in village life outside the church and was at various times involved with the Women’s Institute (WI) and the Girl Guides.

In the 1950s she set down her childhood memories of village life under the title “Memories of a Villager”. They are a delightful, warm account of a way of life long gone and show the love she had for her village and its people.

Miss Faux’s memories end with the following poem which she wrote about the village; they were winning lines in a WI competition in 1946.

A village not void of beauty, in South Northamptonshire. To the passer-by not striking, to its own folk very dear. Its houses, both ancient and modern, are like its inhabitants too.

Some young and gaily painted, some mellow, some aged, but true.

The Duke was a man of strong character who lived to the age of 97, and for many years dominated the life of the village. A number of the village men were employed by him, working either on the farm, or in the gardens which supplied the produce for the house, or in the workshops which maintained the estate, which was large, and included several of the neighbouring villages. The wages of these men were small, the tradesmen earning not more than 24 shillings a week.

I remember so well the women, Mary Morris, Angela Ratcliffe, Charlotte Meakins, Annie Meakins and the others, who, wearing their black hats and their shawls or capes, set out each day to walk from the village up the long drive and in through the stable yard to their work in the laundry, or in the kitchen. Many of the villagers were very poor and gathered to buy dripping at the kitchen door. A large can of milk could be bought for a penny if one took the long walk to the dairy.

I remember being taken to Wakefield to see the oil painting of the Duke presented to him by the county on his ninetieth birthday. The Duke was a regular worshipper at the village church and every Sunday morning I saw the procession of carriages come down the drive, cross the Watling Street and proceed through the village, carrying the Duke, his visitors, and his servants to the church.

It was said that there were two processions on Sunday morning which met in the High Street, one going to church and the other to the bakehouse, where the villagers took their Sunday dinner, consisting of Yorkshire pudding and meat, to be baked for a penny.

The coach house and stables where the Duke’s horses were stabled during the service can still be seen in Church End. [4 Church End has since been built on the site.] The Duke and his servants sat in the chancel which is now used by the choir, and he, a stately figure, would enter through the chancel door, while the servants proceeded to the main door and entered according to rank. What fine looking men they were. The steward, the valet, the butler, the footmen, each wearing a frock coat and carrying a tall silk hat. The female staff were all dressed in black, the housekeeper, the cook, the housemaids, the still room maids, the kitchen maids and the laundry maids, and all had their hats tied with large black bows under their chins.

The vicar was the Rev. Walter Plant and he and his wife (the author of several books) presided graciously over the village and shared the joys

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 86

Hilda Faux and her brother Burrell with their parents. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Collecting the Sunday roast. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Hilda Faux in 1924. [Mrs Phyllis Russell]

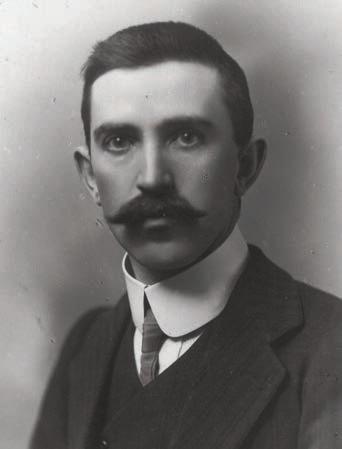

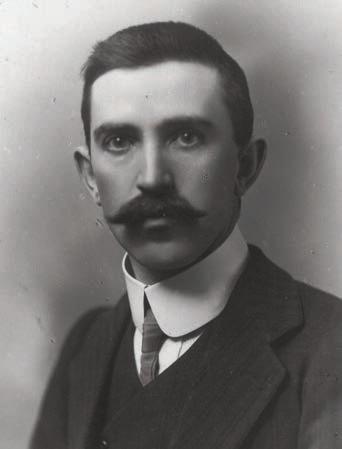

Edward Frederick Peasland

Edward Frederick Peasland was born in the village in 1876 and grew up in one of the cottages that adjoined the Schoolhouse, a row which was demolished in the 1950s. His first job on completing his education was as a school monitor. Later he was employed as a clerk in the stores at Wolverton works. In the late 1890s he became interested in photography and set up his own darkroom. Through his attendance at church and membership of the choir he befriended the vicar of the day, Rev. Walter Plant. For nearly 30 years he recorded the people and events of Potterspury and kept meticulous records of over 400 photographs he had taken.

By the mid 1920s he retired from the works and his love of his family and his garden left little time for photography. He left his darkroom as he had used it and locked away the negatives which he had accumulated over the years.

and sorrows of all. Mrs Plant could often be seen driving round the village in the afternoon in a chaise, drawn by a small pony and driven by the sexton, Caleb Tapp. Mrs Plant did much for the mothers and children of the village: many were the rice puddings and jellies she delivered to the sick.

The church and Wakefield were closely connected, the Duke being patron of the living. It was to

His widow Gladys, who died in 1961, told an eerie story to her children. She was, as a child, an attractive girl with dark curly hair. In the 1920s she went with her sister to visit friends in North London. Whilst there, she went out with the friends who were collecting rents from some large properties in that part of London. She particularly remembered visiting one house where the friendly doctor who lived there sat her on his knee and made a great fuss of her. She was not to know until many years later that her friendly doctor was the notorious Doctor Crippen, later hanged for the murder of his wife!

After Gladys’ death, her daughter Mary (now Mrs Mary Nunnari) opened up the locked attic room and found all the photographic materials, including the negatives still there. We are greatly indebted to her for allowing us to use so many of those photographs to help illustrate this book.

Wakefield we went for our Sunday school treat each year. The farm wagons drawn by horses came to the gates of the school yard and we were helped in. We looked forward to this treat. We had tea in the coach house, ran races, were given bags of sweets and buns, and returned home singing lustily, “For he’s a jolly good fellow and so say all of us” as the wagons jogged along.

From Wakefield came the enormous Christmas tree each year. It was a pole reaching almost to the roof of the school: in it were holes, into which were fixed branches of fir to form a tree. It was then decorated, and there were toys for the boys and a doll for every girl. These dolls were all dressed by willing helpers. The following evening the tree was used for the adults, the charge being sixpence, and they each received a gift. A red tin lantern (with glass sides) into which one could fix a candle was a gift received by my mother and used by her for many years, when going out on dark nights.

Enormous pleasure was derived from concerts held in theschool during the winter, the programme being provided by local artists. We never tired of hearing the same old songs sung by the same singer, and if the vicar and his wife sang, “I will give you the keys of heaven”, and another well known artist sang, “The girl in the clogs and shawl”, our joy could not be measured.

Religion played a large part in the

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 87

Edward F. Peasland [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Mrs Plant in the chaise outside the vicarage preparing for her afternoon outing . [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Teddy Ratcliffe

Teddy was born in Potterspury in 1871 and is remembered mainly as the village carrier who for many years pushed a large hand-cart between Potterspury and Stony Stratford collecting orders from the shops for a small fee. He could neither read nor write, but he could remember all the orders and who placed them. Teddy was much admired for his hard work by the grateful shopkeepers of Stony Stratford who, seeing this slight figure barely visible behind the mountain of goods on his hand-cart, clubbed together and bought him a donkey to assist him in his labours. Alas, Teddy was not very good with animals and his troubles with the donkey became a village legend. One day outside a Stratford shop it collapsed and after

lives of many of the villagers, and there were large congregations at the three places of worship. There was at that time a Methodist Chapel in Blackwell End, and the preacher was Mr Eli Tapp, who worked during the week in Wakefield gardens. This chapel was later closed and made into two cottages. I recall the male members of the church choir, nine of them were faithful members for fifty years, these were Caleb Tapp, Rowland Woodward, Alfred Lambert, Walter Ratcliffe, George Dodson, Walter Green, Harry Henson, Levi Bliss and Alfred Faux.

Some of these men would in the afternoon walk through the fields to Furtho Church where a service was held. I remember going to a Harvest Festival service there and standing in the churchyard to join in the service as the church would not hold the congregation who came to the isolated church from the surrounding villages.

The living of Furtho was united with Potterspury in 1920, and soon afterwards the church was closed. I remember hearing the bomb fall in 1941 which fell near the church and unfortunately shattered the windows

Teddy Ratcliffe in later years. [Milton Keynes Museum]

examining it, a shopkeeper said, “I’m sorry Teddy, but it’s dead”. Teddy is said to have scratched his head and said, “That’s funny, it’s never done that before.” So he had to go back to pushing his hand-cart.

For many years Teddy was the organ blower at the church. For much of his adult life he lodged in Blackwell End, but ended his days in Danetre Hospital in Daventry. He was buried in a pauper’s grave much to the disgust of the Rev. R. G. Richards, the vicar at the time, who was most annoyed that the authorities had not let anyone in the village know. Had they done so, the church would gladly have paid for a funeral for this man who had served faithfully both the church and the people of Potterspury for so many years.

on the north side. The village schoolmaster, Mr A. J. Smith, could be seen each Sunday in frock coat and silk hat wending his way to the parish church to fulfil his duties as organist and, though small in stature, commanded the respect of everyone. He was headmaster for 38 years, from 1881 to 1919.

The organ was blown by hand by Mr Edwin Ratcliffe, affectionately known as Teddy. He walked the three miles from Wakefield Lawn twice every Sunday to perform this duty. He also walked each day pushing his

truck into Stony Stratford, and for the price of penny would do any errand. He took notes into the local doctor’s, and was a source of amusement, for he would often diagnose the complaint as well as deliver the note. He collected medicine from the chemist and often his truck was so laden with parcels that he could not see over them. The Stony Stratford tradesmen later bought him a donkey and cart, but Teddy was not very good with animals; the donkey did not live long, and he reverted to his hand truck. I recall Dr Powell who visited the village driving a grey horse in a

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 88

Teddy Ratcliffe with his cart in Stony Stratford. [Source: Jack Clamp]

high trap; Dr W. Bull riding on horseback; and later, Dr Douglas Bull riding a high bicycle with two bars.

Some of the village men worked in the Wolverton Carriage Works and walked the five miles to reach there by 6 a.m. Later they bought the “Mails”, two horse-drawn covered wagons, and drove themselves, stabling the horses in Wolverton to await the return journey at 6 p.m. [It is from these wagons that the village newsletter, The Old Mail derives its name.] In the village one was kept in The Ropewalk, which was no longer used for rope making, and one was kept at Mr Charles Stewart’s farm. Mr Stewart also had a covered cart and carried on a carrier’s business, driving the twelve miles into Northampton on Saturdays. He would also take passengers. We sometimes travelled with him to Collingtree to visit an uncle. We did not often go to Northampton but I remember walking to Castlethorpe to catch a train and walking back over the fields carrying the shopping.

A party wishing to visit Northampton or go out for a drive as we sometimes did when we had visitors, could hire a wagonette or brake from Jefcoate’s the local baker who had them for hire. Mr Jefcoate also had a fly drawn by two grey horses, Prince and Trilby, as well as a fine horse drawn hearse for hire.

As I walked to school I often saw

the lacemakers wearing starched white aprons sitting at the door of their cottage with their pillows, twisting their bobbins. I was fascinated by the twisting of the bobbins and the “sticking a pin”. Some of the smaller patterns were: the fan, the running river, and the spider. The patterns were pricked out on a strip of parchment. Great pride was taken in the pillows and the prettiest prints were used to cover them and for the cloths, and the prettiest beads for weighting the bobbins. The lace was at that time bought mostly by Mrs Chettle, a farmer’s wife who lived at “The Beeches”. She was a lace buyer and paid as little as twopence a yard

for some lace. [John Chettle was the farmer at Beech House Farm, he was a churchwarden and member of the Parish Council for many years. His grave in the cemetery is marked by a beautiful, hand carved, oak cross.] I came to know one of the lacemakers very well. She was Mrs Wootton who made lace for several members of the Royal family and some to trim the clothes of the present Queen when she was a small child. I recall Mrs Wootton telling me that she was twice widowed and left with a family of six, four boys and two girls to bring up on six shillings a week. To provide for the family she went out to work for a shilling a day and made lace at home. Mrs Chettle sometimes held lacemaking schools to encourage the making of pillow lace. My mother went to one of these schools. Mrs Chettle also ran a clothing club for the villagers. At certain times of the year the amount entered on the card could be spent. An outing to Stony Stratford or Towcester to spend the “Club Card” was an event looked forward to by many families.

Later a coal club was formed by some of the villagers, and after a time they were enterprising enough to buy their own railway coal truck. This club flourished for many years until the ill-health of the secretary, Mr A. Lambert, and the rationing of coal made it impossible to carry on.

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 89

Jefcoate’s fly with the two horses, Prince and Trilby. [Source: Jack Clamp]

Mr and Mrs Chettle in their summerhouse at The Beeches around 1900. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Many of the cottages had a pig sty and large pots of pig food were always cooking on the old black grates. Pig killing days were red letter days to the owners and their friends.

There were many tasty delicacies to put on the table such as black puddings, faggots, chitterlings, home made lard, bone puddings and bone pies. The pigs were killed at home and we children loved to watch the singeing process. The pig was placed in a pile of straw, the straw was set alight, and the flames leapt high.

The owners would sometimes canvas the village for orders for the home killed pork, or they would cure it for bacon. Huge sides of bacon and large hams could be seen hanging on the walls. Some people were the proud possessors of a salting lead in which the bacon was salted. This they would lend round to their friends.

Large quantities of home made wine were made from cowslips, dandelions, sloes, potatoes, elderberries, plums etc. Large red pans of wine, with a piece of toast floating on the top could often be seen under the parlour table going through the process of fermenting. It was then stored in large stone jars, and when friends called a glass of wine was always offered.

There were many wandering visitors passing through the village. Vagrants on their way to spend the night in the workhouse at Yardley

Gobion carried a tin can and often called at the houses asking for boiling water to make tea. After spending the night in the workhouse they had to break stones for road mending before starting on the road again. There was a dancing bear led by its owner on a long chain, the horse drawn gypsy caravans with their wares to sell, and the barrel organ complete with monkey holding a cap to collect the pennies: these paid regular visits. A blind man (Blind Barley) played a concertina and was led by his dog; an old soldier with only one arm sang lustily, “Three cheers for the red white and blue”. They came at regular

intervals and we always gave them pennies.

The old cattle drovers who brought the cattle from the markets to the butcher’s were familiar figures and when the poor frightened beasts were driven through the village we children scattered and got inside a garden gate. I remember by name two of these drovers, “Towcester Toff” and Tom Nicholls. Tom Nicholls father was “Sooty” Nicholls the local chimneysweep. He would walk from Yardley Gobion and sweep the chimney for three pence.

A travelling theatre occasionally came into the Reindeer yard, and performed such plays as “Murder in the Red Barn”. I remember also a travelling cinematograph show, which presented “From the Manger to the Cross”. The Watling Street was a very different scene with the horse traffic, the early cars and the steam engines. Lyons Tea vans were pulled by these engines and they stopped at the brook to draw water. I remember the day when the thatched roof of Mr C. Stewart’s farmhouse was set on fire by a spark from one of these engines. We watched the fire engine drawn by horses arrive. Thethatcher at that time was a familiar sight, renewing the thatched roofs. These have almost disappeared, six remaining.

There was then a thatched public

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 90

Walter Wise who lived on the Watling Street pictured in his garden about 1900 with his pigs. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Pages from “Memories of a Villager” by Hilda Faux.

house in the Lower End known as “The Blue Ball” which had the unusual sign of a red heart above a blue ball and bore the Latin inscription “Cor Supra Mundum”. [Lower End is now known as Church End.] I was told by an old lady who had lived there about 1895 – 1900 that it was thought that there was only one other sign like it. (It is, I believe, still [in the 1950s] in the possession of Capt. Atkinson of Cosgrove Priory.) Mr James Bryant, the first policeman in the village, was also licensee of this inn. The blacksmith’s shop was always and still remains [in the 1950s] a place of interest. The blacksmith Mr Sydney Smith was one of a family of blacksmiths, his father and brother also working at the forge. We saw the horses being taken there to be shod, and to be roughed in the bad weather. Now [in the 1950s] there are few horses and the blacksmith, Mr John Smith, is occupied with mending farm implements and doing wrought iron work. A fine piece of his work is the seat standing [even to this day] on the piece of grass near “The Mansion” [now known as Potterspury House].

Whilst writing of horses I must mention the fine stallions which walked through the village on their way from farm to farm. These were beautiful creatures, well groomed and their tails and manes plaited and braided with coloured braids. We all

ran to see one pass or to watch it when it halted in The Anchor yard and the man in charge still holding it would call for a mug of beer. [The Anchor was for many years the village’s favourite pub. It was demolished in the 1960s.] We saw the followers of the Grafton Hunt in their hunting pink pass through the village on their way to and from the meet. The hounds were often brought through the village when being exercised. Some of the local farmers “walked” a hound puppy. The puppy was kept until the Puppy Show and then returned. A prize was given for

The Blue Ball Inn

The premises of the Blue Ball Inn, reputedly dating from the 16th century, still stand at 6 Church End not far from the church. It is believed to have closed as a pub in about 1912. To the right of the main building is the brewhouse. To the left, older pictures show stables once used for the duke’s horses during church services. Sam Gibbard remembers his father telling of coming over from Puxley to watch gipsies dance and play the fiddle outside. Although little is known about its days as a pub, it is remembered for its curious name and even more curious sign: a picture of the world, painted a bluish colour (not dissimilar to the Earth’s appearance as viewed from space!) with a small red heart above it. Beneath the picture was the Latin inscription Cor Supra Mundum (‘Heart above the world’).

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 91

Mr and Mrs Fairchild of The Cottage, Poundfield Road, about to take an excursion on their motorised three-wheeler in the early 1900s. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Lower End with the sign of the Blue Ball Inn visible in front of the stables in the early 1900s. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

The Red Lion Inn

Not much is known of the Red Lion on Watling Street in its days as an inn. It was still an inn in the early 20th century, but has long been known as Sunnyside Farm. Dick Bailey, the last farmer, knew the small building at the rear as the brewhouse. There were still pipes for cleaning barrels in the 1940s.

the best puppies.

There were certain days that we all looked forward to:

B OXING D AY , when the brass band from Yardley Gobion came round and always played “The Mistletoe Bough”. They called at many houses for a glass of home made wine.

GOOD FRIDAY, when after the service in church it was the custom for everyone to go to the woods to gather primroses, and there meet people from all around the district.

EASTER MONDAY, when we watched the people going along the Watling Street in horse drawn brakes, wagonettes, gigs, etc. on their way to Towcester races, which were then held only once a year. We would patiently wait to see them return, when those who had been lucky would often throw pennies for the children to pick up.

MAY DAY at Yardley Gobion, when we went to see the May Queen crowned and to watch the traditional maypole and Morris dances. Until recently there was no May festival in this village. It was started by the local WI.

R OGATION S UNDAY , when we followed the vicar and the choir after evening service to the fields and allotments to bless the crops.

WHIT TUESDAY and WEDNESDAY were “club holidays”: Tuesday, the Oddfellows Club, and Wednesday, The Old Benefit Club. These “holidays” were held in the field called Tattnell. In the afternoon there were such attractions as the village band playing rousing tunes and a stall where you could buy ginger snap and rock. There were races and a greasy pole with a leg of mutton at the top

for the one who could get to the top. There was also a revolving wooden horse, which you mounted at the tail and endeavoured to reach the head. It was fun to watch. The competitor would mount and carefully scotch along, but before he could reach the head, the body twisted round and he was thrown off.

On either A UGUST 1 ST or 2 ND we always walked into Stony Stratford to visit the fair held for two days on the Market Square. Then there were the “Mummers”. They would come any time between OCTOBER 31ST and PLOUGH MONDAY (the Monday after January 6th). The “Mummers” were a band of men out to make merry. They were dressed chiefly in paper, paper skirts, paper streamers, hideous masks and headdresses. Often they were in the form of animal heads. I did not like the “Mummers”, but I believe if they came to the house you were more or less obliged to ask them in.

I remember Major and Mrs Brougham who lived at “The Mansion”. He read the lessons in church on Sunday morning and he founded the first troop of Boy Scouts in the village in 1912. Their daughter married Viscount Ipswich, who was killed in a flying accident in the 191418 war. She was the mother of the ninth Duke of Grafton, killed in a motor cycling accident when he was 21. She gave the war memorial in the church in memory of her husband

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 92

Harvest time at Sunnyside Farm. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

The Anchor Inn in its heyday. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

and the window above, depicting “The Crucifixion”, was given by the village as a memorial to those who died in the 1914-18 war.

Mrs Newton and her family lived at Pury Lodge, and were often seen in the village. (The Newton family were co-founders of Winsor & Newton, the art material manufacturer.) After her death it was bought by Mr G. Beale who became Sheriff of Northamptonshire. He built the chapel in the grounds, which was used as a Catholic chapel. The house is now used as a school for maladjusted children.

In my childhood whole families including uncles, aunts and cousins could be seen walking out together on Sundays, and the walk along behind Pury Lodge to the tree known as the “Queen’s Oak”, where Elizabeth Woodville was supposed to have met Edward IV, was a favourite one. The summers then seemed hotter and the winters more severe. We picnic’d in the hayfields and played around and jumped the haycocks. My friends and I always took the lace that we were knitting on fine steel pins with very fine cotton and many a needle was lost in the hay.

I saw the gleaners at harvest time setting off with their prams and trucks, with a pocket apron tied

around them in which to glean the short ears. Some families gleaned enough corn to keep them in flour all the winter. The corn could be taken to the village mill, then worked by the old water wheel and owned by Mr Busby, who would grind it on payment. The villagers also collected acorns which they sold for pig food.

Often in winter the snow was deep and we waited for the snow plough to come down from Wakefield before we could go to school, and there seemed to be long spells of skating and sliding on the Wakefield lakes. People came from over a large area to skate there, and on bright

moonlight nights there were often supper parties on the ice. The local skaters who could cut a figure of eight were much admired. A chair was provided to help those not quite so proficient. During the cold weather soup could be bought at certain times from Hill House (now Greystone Lodge), the home of the estate manager of the Duke of Grafton. It was sent down from Wakefield and people went with cans to buy it.

I remember the large band of young men who set off so light heartedly one morning to join Lord Kitchener’s army, and the Belgian family, Madame De Keyser and her three children, Isidore, Alphonse and Marie, whom the village adopted in the 1914-18 war. They were a sad family who had seen the father shot by German soldiers. Many of the villagers made weekly contributions to provide them with an income. They had their own home and lived in the cottage now known as 47, High Street. ‘Madame’ was a good needlewoman and able to take in dressmaking. They returned to Belgium after the war.

Our postal address in those days was Potterspury, Stony Stratford, Bucks, and our letters were brought by a postman who walked from Stony Stratford to the village, and on to deliver at Wakefield Lodge. The village post office has been kept by the Osborne family for many years. I can recall three generations serving there.

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 93

The drawing room at Hill House (now Greystone Lodge) in about 1900. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

An early ‘pink day’ when clove pinks were sold in aid of Northampton General Hospital. (Alex Wootton]

For many years they also ran a wheelwright’s and undertaker’s business.

The only newspapers we received during the week were the Northampton papers. These were brought by a small lame man, Mr “Georgie” Webb, who lived at Yardley Gobion. He cycled to Castlethorpe station to collect the papers and then delivered them to both villages. On Sunday Mr Wamsley came from Stony Stratford in a pony cart.

The villagers have always been fond of sport and there was a football match played every year between Potterspury and Yardley to decide the fate of the “Watercress Cup”. It was only a wooden cup, but was coveted by both villages. There were also cricket and tennis clubs.

About 1916 the first of the “Pink Days” was organised by Mr A. Wise of Blackwell End, who grew large quantities of clove pinks in his garden. These were made into button holes and sold in the neighbouring towns and villages in aid of Northampton General Hospital. Then followed the Hospital Fetes which for many years raised large sums of money for the hospital. Before these efforts a collection hadbeen made in the village annually.

The first company of Girl Guides was formed in the village in 1917 and in about 1919 a bus service was started

on Wednesdays and Saturdays from Northampton to Stony Stratford by Grose’s Ltd. This passed through the village and transport out of the village became easier. The six o’clock bus on Saturday evening, an open double deck, solid tyred bus, could be seen leaving the village loaded to its fullest capacity. There were no restrictions, and passengers sat on every step of the stairs and even on the ledge which protruded over the driver’s seat. The return journey from Stony Stratford was at 9 p.m.

In 1918 the seventh Duke of Grafton died and soon afterwards the estate was sold. Many of the tenants bought their farms and cottages and became land and property owners (1920). Later Wakefield Lodge was sold and the quiet dignity of the Grafton family passed away, and the bond which had bound Wakefield and the village so closely together was broken. In 1920 the house was bought by Lord Hillingdon and modernised. It was later sold to Mr Gee who demolished a large part of it and it is now [in the late 1950s] owned by Mr Richmond-Watson.

Memories of times around the 1920s

Mrs Irene Davison

I am 87 years old (in 1999) and lived all of my childhood in the village but as things were at that time we girls had no option other than to go into domestic service at the age of 14 when we left school and the boys had little option other than the available farm work around. Potterspury really was a village then, everybody knew everybody else from one end of the village to the other. Although it is still known as ‘the village’ that is in name only, as I am sure that more than three quarters of the people do not know the others. With more new buildings and new younger people, the divide becomes greater as time goes on.

Most of the village consisted of small, thatched cottages with just one room downstairs and two upstairs, no bath, no running water, no electric light, only a small fire grate with a tiny oven and a small tank at the side to heat the water which had to be carried in buckets from a stand pump in the lane. Most people had a large tin bath which used to hang from a nail in the wall at the back of the house, so we did have a bath, but only once a week. Water had to be heated on the fire in kettles and saucepans to get enough to fill the tub, and, with families of seven or eight children, which were the norm in those days, the cleanest had to get in first and so on until the dirtiest was the last in.

This then, was life in our village in the early years of the century. We will now turn the clock forward some 1020 years and read of Mrs Irene Davison’s recollections of village life in her younger days.

Another unhygenic thing was the toilets, or closets as they were known, which had buckets that had to be emptied once a week, but the powers that be were considerate enough to make sure that this chore was done late at night because of the foul stench. The men who undertook this unsavoury job were allowed an ounce of tobacco to enable them to smoke and try to alleviate some of the stench. The children had a name for this contraption, shaped like a tank and pulled along by a horse, it was called “the sweet old violet cart”, and you couldn’t get anything less like violets

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 94

Harvest at Beech House Farm in the early 1900s.

[Mrs Mary Nunnari]

anywhere. Apparently it didn’t do the men who operated this cart much harm as they lived to be over eighty. I don’t think they were paid very much and certainly not danger money.

Although the village was small it boasted about six pubs. Two were before my time, but I remember four main ones, the Old Talbot, the Anchor, the Cock, and the Reindeer, each having their own clientele and of course there was the usual friendly rivalry between them all. There was also a good deal of drunkenness at weekends. Most of the men had quite a large back garden and were mostly self-sufficient in the way of vegetables, fruit, etc. Even though they worked hard all week and often had to walk miles to work (as there was no transport), they also worked hard on their gardens, and I suppose they thought that they were entitled to get drunk at weekends, but I don’t think there were ever any fights. There was no television, and no birth control aids, and a family of seven or eight was the norm. In fact a relation of ours had fifteen, the youngest didn’t know their eldest brothers, who had been out to work since the age of 13. As soon as they reached that age they had to find a job: it was one less mouth to feed, and even if they only earned a few shillings it helped.

There were quite a few organisations in the village then, Potterspury even had its own brass band, which always turned out on

festive occasions and paraded through the village. There was a thriving Boy Scout troop and Cub Scouts, and what was then known as the Girls’ Friendly Society. The Church was represented by the Band of Hope (The Church of England Temperance Society) encouraging villagers to forsake the demon drink!

In our days as children you could walk from end to end of the village and not see a car, how else would we have been able to play with our whips and tops in the road and bowl our hoops along. There was certainly no lack of exercise then, we spent nearly the whole time out of doors in the summer, walking through the woods, collecting wood for the fires to save coal, and we found joy in walking

through a field of buttercups where you got your shoes covered in the yellow pollen and we would pick violets from the hedgerows. Later in the year we had fun picking blackberries. These things mean nothing to many children of today, they would probably say “How boring!”. They have so much today, but are they any happier than we were with our simple pleasures, and no spending money? We were all in the same boat and there was no jealousy.

Another ritual which was peculiar to this village as far as I know, was when the horse racing was held at Towcester. It was an event that only happened twice a year at that time and the one that affected us was the Easter Monday event. We used to watch the wagonettes and the horse drawn carriages and pony traps etc. parade through the village on their way to Towcester. We thought they were toffs as they were the only ones who could afford to go to places like that. When it was time for their return from the races, I think the whole village would line both sides of the Watling Street and put up a rousing cheer to every carriage that appeared, and if the occupants of the vehicles had had a good day with some wins at the races they would throw a handful of pennies into the crowd and we would scramble for them. I often thought the “toffs” would think that there was not just one village idiot but a whole village

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 95

The row of old cottages on Watling Street that stood where Churchill Motors is now. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

The Band of Hope in the early 1900s.

[Mrs Mary Nunnari]

full of them! But it was a fun thing for us and we looked forward to that event as well as a chance to pick up a few pennies.

Another annual event to which everyone looked forward was the British Legion Fete held in one of the fields next to the Watling Street. That was a big “do” as the village brass band headed a procession through the village, next came the men of the British Legion, then the troops of boy scouts and cubs with an assortment of bugles and drums. They must have made a hell of a noise, but it was all excitement to the crowd of kids following, running and jumping in time with the marchers.

Each of the men took charge of a sideshow including the greasy pole. This was a pole about ten feet high, planted firmly in the ground and covered with inches of thick cart grease. Whoever managed to climb to the top was the winner of a piglet given by a member of the team. That was a real win as the piglet was fed and reared and then killed at an appropriate time, and provided food for a family for months to come. There was always a good atmosphere of friendly banter amongst the men.

Funerals were appropriately respected by everyone, as the mourning family congregated at the home and the coffin was placed on

the bier carried by four of the funeral directors and then paraded in silence from the home to the church. Anyone passing by at the time would immediately stand still with bowed head. Boys and men doffed their caps and stood still until the cortege passed by. There were no cars in those days.

Sundays were also revered and observed very strictly. Children were

not allowed to play rumbustious games or behave in a disrespectful manner, a quiet walk down to the church – which in those days was quite full – then it was Sunday school for the children in the afternoon and church again in the evening. There was always a full choir – boys and men, ladies and girls. After church there would more often than not be a sedate walk up to the woods or fields with our parents: no playing or mucking about in case we made our Sunday clothes dirty – anyway it was Sunday and that was to be respected and observed.

In those days there were no fridges, milk was brought in large pails to your own door, served in half or one pints from measures hanging from the side of the pail. Bakers brought bread, unwrapped and without any thought of hygiene and yet I am sure there was less food poisoning than there is now. Butchers hung up their meat in open windows and displayed other cuts on the open shelf which attracted a good supply of flies. We just washed it, not knowing if the water was polluted.

At least most people were fairly

The Night Soil Cart

We have already heard from Mrs Davison about the ‘night soil’ cart and its nocturnal progress around the village.

Prior to 1946 a horse-drawn cart was used to collect the contents of village privies and transport them for emptying on nearby fields. The horse and cart were stabled at Charlie Foster’s on Watling Street; Will Atkins and Harry Sumners had the job of emptying the buckets. It is said that Harry used to delight in catching people ‘on the throne’. To compensate for the fragrance which accompanied their work these men were provided with a tobacco allowance to divert the attention of their noses from their work!

Once a motor vehicle ran into the cart on the A5 necessitating a less than pleasant clean-up operation before any traffic could pass by. On another occasion it is said that Will dropped his jacket into the cart, and was trying to retreive it, when his mate consoled him saying, “Don’t worry, it’s only an old jacket.” Will is said to have replied, “I’m not worried about the jacket –it’s the sandwiches in the pocket I’m after.”

In 1946 the old cart was replaced by a motorised version. Whilst this meant less arduous work for the men it didn’t do a lot to reduce the smell. Relief came in 1954 when, much to everyone’s delight, the mains sewers were laid in the village. One local custom, which is unlikely to be sadly missed, passed into history.

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 96

A brass band procession along the High Street in the early years of the century. Notice Woods farmhouse (The Cottage Stores) on the left. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

sure of a good Sunday roast, thanks to the two bakers in the village (one in the High Street, the other in Blackwell End). It was the custom to allow anyone who wanted to prepare their joint surrounded by good wholesome Yorkshire pudding in a large baking tin, to bring their dinner up to the bakehouse to be baked in the large bread ovens. The charge for this was one or two pence and they were duly collected at the appropriate time ready for the Sunday lunch along with a goodly share of home grown vegetables from the back garden.

We gain a further insight into the nature of local employment and village life in pre-war years from Henry Stewart’s recollections.

Some recollections of times around the 1930s

Henry Stewart

I was born in 1917 in Cock Lane (now Sanders Lane). The houses had no numbers in those days. My parents, James and Charlotte, had also been born in the village. I was the eldest, and I had four younger sisters.

I attended the old school in the High Street and left in 1931, when I was 14 and went to work at the gravel pits in Cosgrove; now the Lakes and Caravan Park. Mr Whiting was the owner in those days. I was in charge of two ponies, with which I would take gravel from the pit to the washer. It was then graded by riddles and put into large piles. My wages were £1-10s (£1.50) per week, and out of that I was stopped two shillings per week for my Insurance Stamp. I stayed in that job for two years. It was hard, cold work, as I worked in wet conditions all the time. When I was 16, I was employed in the gardens at Wakefield Lodge, working under Mr Lampard, the head gardener. That was a lovely job, but the wages were poor. I was still only getting £1-10s a week when I left, aged 20, but I couldn’t ask for a rise, as jobs were very hard to get. I did a few other labouring jobs around the village until 1940, when I went to work for Iron Oxide in Deanshanger.

I stayed there until I retired in 1982, when I was 65.

My family and I moved to 37 Watling Street in 1936, and my parents ran a shop from the house. We used to sell groceries – tea, sugar, flour, sweets, and such like. In those days the customers would tap on the small window at the front of the house and my mother would open the window to serve them. After a while

Local Dialect

If you live in Pury you don’t have afternoon tea, you ‘ave a bit a cairke an a cup a tay in a bairsun!’ Bill Druce, who lived at Holly House, Watling Street, used to tell the tale. “Oy wen owt fer a wark wun day un oy were a runnin down the strit wen oy met a dug a follerin me. Oy tuk it um we me un chairned it ter the bed powust wee a bit a string, un wen oy woke up in the mornin, theyer it wor –gorn!”

Mrs Aggie Bason, who lived in a cottage fronting onto the footpath of the Watling Street where Churchill’s Motors (next to Holly House) is today, had quite a broad accent and delighted in telling this tale. “Oy were a sittin ere in the front a me fyre wen the room suddenly went dark. Oy looked up un see this great fairse ut the winder, it were un ole tramp! It frit me ter death!” (Aggie lived on to tell the tale.)

she decided that it was undignified to leave people standing outside in the road, so she let them come around to the back door.

Then they decided to expand the business, so they bought two fish fryers second-hand, and started a fish and chip shop from one of the two wooden sheds which still stand in the back garden. The lads used to come around for fish and chips when the Anchor pub closed, and if the weather was bad my mother would let them sit in the other shed, out of the cold, to eat their food. We didn’t think much about it in those days, but frying in that wooden shed must have been a terrible fire hazard!

One of the highlights of the week was the Pury Brass Band. They used to practice in the Cock Inn during the week, and then, on the Sunday

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 97

The butcher’s shop in the early part of the 20th century. [Source: John Giddings]

The Reindeer Inn

Now the premises of Reindeer Antiques Ltd, an antiques dealer of international repute, the Reindeer was until the mid 1960s a pub, owned by the Northampton Brewery Company. It had long been a coaching inn with a large yard, stables, coach houses and had its own maltings. Records of the 18th century show churchwardens holding meetings there. In the late 19th century, before the Parish Council existed, this was where the Waywardens met to appoint the Constable and carry out other duties which are now the responsibility of the Parish Council.

Beryl Gibbard and Keith Solesbury recall: “When Appleton kept the Reindeer, they used to have a band on a Sunday night on the lawn. It was Duggie Blunt’s Band. One day when they put all the instruments down to go inside and have a

drink, Ginger Lambert tipped half a pint of beer in Duggie Blunt’s saxophone. Well, when Duggie went to play it he couldn’t get a sound out of it! Duggie wouldn’t play there any more.”

“There was another old boy who used to get in the Reindeer, Gerry Richardson, who used to live in one of the cottages just below the Anchor. When Gerry came in for a couple of pints on a Saturday he would wear the biggest flower on his coat you ever did see. As soon as he had his couple of pints he would put his trilby on upside down and start dancing. Somebody tipped half a pint of beer in the hat one night.”

Reindeer Inn on Watling Street in the early 1900s. [Mrs Mary Nunnari]

Beryl’s husband Sam remembers the occasion when a big Guinness tanker crashed on to its side against the Reindeer and poured Guinness into the bar!

evenings when the weather was good, they would assemble on the grass bank opposite the Anchor Inn on the A5 and play for an hour or so to an audience usually made up of the locals.

Before the Second World War, a man named Freddy Howard used to live in one of the cottages in Blackwell End (before the council houses were built). He owned a little Ford truck, and on Saturday mornings he would drive over to Castlethorpe railway station, and load up with coal, which he would then sell around the village for a shilling (5p) per hundredweight (50 kg). When he finished selling the first load, he would return to Castlethorpe, load up and then go to Paulerspury in the afternoon, and repeat the process. Talking of coal, my parents told me about “Potterspury Coal Club”. Village residents would pay a shilling per week into the Coal Club, and then, when they had paid in £1, they would be entitled to collect a ton of coal, which would help to see them through the winter. So many of the old ways have

disappeared. When I was a youngster, it was customary on a Sunday morning for my mother to send me around to the bakehouse in the High Street, with our Sunday joint and a bowl of batter to make the Yorkshire pudding. Mr Jefcoate would charge 2d (1p) to cook the joint and make the Yorkshire in the bread oven. The men would go to the pub for a pint

on Sunday lunch time, and would then collect their joint from the bakehouse when it was cooked. On more than one occasion, the men would stay too long in the pub and later return home with a much smaller joint than the one they took in, but if you went in early, you sometimes got one bigger than you took in. There used to be the odd dispute about this,

POTTERSPURY THE

AND ITS PEOPLE 98

STORY OF A VILLAGE

Sunday roasts at Jefcoate’s bakery.

[Milton Keynes Museum]

The

and if news was fairly scarce in the village that week, a short story about the dispute would appear in the local newspaper, The Wolverton Express

At about this time, Dolly Russell’s father came to the village. Older villagers may remember him giving rides to the children in return for jam jars or old rags. We are fortunate therefore in having Dolly’s own account of her life as a child and their arrival in Potterspury.

A life with horses in the 1930s and 1940s

Dolly Russell

Dolly Russell

My Dad, John Hammond, was a horse slaughterman: my grandad was blind and ran a merry-go-round. They came from Dorking and Dad married Bertha, my Mum, and they had 14 children. Mum was ill with tuberculosis and the doctor told Dad she would only live if she had an outdoor life so he bought a caravan and some horses and gave rides to children. Then Dad decided to go back to slaughtering and we settled up by the cutting at Dunstable when I was four years old (in 1929) with my brothers and sisters, Kit, Tom, Dora and Stan. They built a big slaughterhouse far enough away from a built up area as you had to be with horse slaughtering. You had a deep pit where all the blood went and when we brought the animals home we used to string them up and bleed them and then load them on trolleys and take them to Redbourn where they went over to Belgium for human consumption during the war.

Dad also collected bottles and jars. We had a big tree outside with bottles hanging up there and jars and old antique bits of iron and stuff and he became known as Jam Jar Jack. He was a character, a loveable rogue, and he used to say to us that whatever he’d done he’d never hurt anyone and he’d never got caught. Then my brother,

Stan, who used to look after all the carts and lorries, being 18, had to go in the army (in 1939). I was 14 or something, I’d left school and I wanted to join the forces to be a nurse but Dad wouldn’t let me. He made me go and take a test to shoot a captive bolt which is like a revolver which shoots a bolt into a horse’s or cow’s head and kills it. So I had to do Stan’s job while he was away in the army for six years. It was hard work, I’d only just left school then and we kept the business going with the trolleys and then Dad started buying horses and bought land near Bletchley which is where he started the Bottle Dump. (One of the roundabouts on the outskirts of Bletchley is named Bottledump Roundabout.) My Dad and his mate, Johnny Bowen, used to go down the New Forest, buy wild horses and bring them home and we’d have a ring and we used to break them in. I had a little one, a tiny pony, and we bought a little trolley thing for it and gave the kids rides. We used to go out with all the 23 ponies and that’s how I came to live round here.

We used to travel miles and we’d come to a village like this and go to the school and see the teachers and say, “Right, we’ll give the children rides, three jars or threepence a ride.” We used to take the jam jars home, wash them and take them back to the jam jar factory at Redbourn and that helped the war effort because bottles

and jars were worth a lot of money. We came out here with the ponies one night; we drove from the Bottle Dump, and we came to this village through Puxley way, Dad driving a trolley, cart or trap of some sort and I was in a Victorian trap, a landau, which dipped in the middle. We used to put a pole in the middle and put a big sheet over at night and sleep in it; we used to put a bed in it, and we’d got 23 horses tied behind. At the turning up near Wakefield along the hedge, Dad said, “We’ll pull in here for the night.” So we put the conveyances on the side and then we had long chains, really long chains, on each pony or horse and you’d get under the hedge and fasten it. You’d measure it out so that they didn’t touch all along the hedge, all 23 of them.

At night time, Dad said, “Let’s go across to the pub (the Reindeer), I know old Charlie Foster.” Now Charlie Foster was a character; he kept rabbits down his yard. Well we went and had a drink and went back and went to bed. When we woke up next morning all the horses were missing; it was real funny. So the next night Charlie Foster said, “You can put them in my field,” That was the field by the brook where the big house is now, but he didn’t tell Dad there was no wall alongside the brook and the next morning when we got up all the horses were gone again. Well

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 99

Dolly Russell seen here with her father’s cart

[Dolly Russell]

apparently, I’ve been told by the villagers, they came galloping through the village up Cock Lane with all those chains clanking and frightened the life out of the villagers. Dad told me to bike back home, because we always had a bike with us, and get Betty, that was the pony we also had, put her in the flat cart and go and look for them. So I biked back to the Bottle Dump which is 14 miles from here, and got Betty and put the bike on the flat cart – we used to build all the carts and things that we used. Anyway, someone had spotted them behind May’s Cafe and down near where the fish farm is now and we had to go and round them all up. The village talked about that for ages and ages, they’d never seen anything like it, they’d never seen so many horses together anyway. For about three months Charlie’s was our stable place rather than going home every night and we went to every little village for miles around, and then we’d come back to Charlie’s and sleep in the landau. Dad used to go down to Charlie’s yard to feed the rabbits. Dad, Freddie Osborne and Chuck Broad,

who were young fellows when I first came here, used to congregate down by the Anchor. I weren’t a bad looking person then, I had hair right down to my waist, I could ride and I could drive and the village boys hadn’t seen anything like that, you know, a woman in jodhpurs and riding boots, and to them I was a novelty I suppose. I got to know Bill and he used to bike over, sometimes I’d be at Aylesbury, Banbury, or Bicester, but eventually we got together and got married. We came back here to live in 1946 in a tiny little cottage with Bill’s parents. The door was narrow, the windows had little leaded panes, you had to have an oil lamp on all day and we went up a rickety staircase to the one bedroom and that was where I had my eldest son. It was on the A5 between the old row of houses next to the brook and the Anchor; there used to be Ethel Richardson, then me, Violet Blunt and her husband, then Ada Mason and then the Anchor.

My eldest son’s name is William John Henry, but when Dad came over he looked at him (he was in a drawer; we couldn’t get a cot), and he said,

Wartime in Potterspury

Like most English villages, Potterspury was affected by the two world wars which blighted the 20th century. We have relatively little information on the effects of the First World War. We do know that the war memorial in St Nicholas Church records the loss of 20 men from the village. The Parish Council had a lengthy discussion on how villagers should be warned of an imminent bombing raid by the German Zeppelin airships. It was suggested that the church bells be rung, but this was considered unwise as it was thought it could also warn the Zeppelin pilot that he had been spotted!

During the Second World War the likelihood of bombing here may have seemed remote, but at nearby Wolverton one local school master whose Austin Seven was his pride and joy was reputed to have camouflaged his little wooden garage! Bombing became more of a reality when a stray German bomber jettisoned a bomb which fell at Furtho damaging the church slightly. Keith Solesbury remembers hiding under a table when that bomb was dropped, and going over next day to see if there was any damage. He also remembers watching a plane come down on fire at Yardley Gobion; it was crewed by Canadian airmen on a training flight. Some bombs were dropped on the Wakefield estate and there are still craters visible by Bears Copse near The Kennels. A landmine fell on a dutch barn at Paulerspury which caused piglets to run amok through the village. It is thought that most of these bombs were jettisoned by planes returning from the raids on Coventry or Birmingham.

Winter Sports

Before the Second World War skating on the Wakefield lakes was very popular and on cold winter evenings cars would gather round the lake to provide light for the skaters. The mill dam was also very popular for skating and when snow fell the kids would all take their toboggans up Duffers Hill and sledge down to the brook.

“Hello, rusty balls” so it stuck and he’s been called Rusty ever since. I kept going on at Bill to go and get us a council house and they started building down here (Furtho Lane) and for two years I walked down here every day, I saw every one of these houses built, though I didn’t know which one I was going to have.

The first villager I really knew was Ruth Salmon, she was married to Vic Salmon who now lives down Sanders Lane. I was walking down the street one day, Dad had bought me an old maroon coloured pram and I was so proud because in those days you couldn’t get prams because it was wartime, and this tall girl went by me wearing a scarf, she always wore a headscarf. She kept looking at me and I mean I don’t know anyone in the village so I looked at her and said, “Am I wearing something? Have I got something belonging to you?” Well she walked off, but she knew me the next time we met. I weren’t used to being stared at like that, you know, looking me up and down as if Iwas a freak, I think it was the pram really! Well I got to know Ruth and we were very good friends. Then I moved, but she got a house down here first and helped me a lot with the kids (Dolly has six sons and a daughter).

Some more recollections of family and village life around about the time of the Second World War come from Joan Goff.

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 100

The Anchor Inn

Kept for several generations by the Pratt family, the Anchor Inn, at the corner of the High Street and Watling Street, was reckoned to be the village’s most popular pub. It was very much the centre of action. (In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were a good many more houses on Watling Street and very many fewer in the centre of the village.) The football team used to meet there, and for a time had changing rooms there.

Memories of times around the 1940s

Joan Goff

When I was a child there were a number of shops in the village: Mr Hemsworth’s in Blackwell End (now nos. 58 and 60) and Aunt Lil’s which was in a thatched cottage also in Blackwell End (now Ashwick) where Mum (Daisy Tapp) would go and get her groceries with the thirty shillings a week that my Dad (Eden Tapp) gave her. Then there was the one in the row of cottages along by Soper’s farm, it was a little sweet shop where you could book the bus to London. There was a farm where the Cottage Stores is now, and the farmer used to give broth to the poor, he made it from sheep’s heads, and many a time my Mum would send me down there for some. There was also a shop in Furtho Lane and where I live now in Blackwell End was an orchard and opposite were allotments.

Mum had 12 children, six boys and six girls and nine of them were born while they were in a two bedroom cottage in Blackwell End. She took in washing to help out, she did all the washing for the Nelson cafe (now the Super Sausage Cafeteria). She’d wash all the filthy tea towels and she’d worry that she couldn’t get them

white because they were so dirty. She’d get a penny for each tea towel. During the war she did all the officers’ washing from Wakefield when the soldiers were there. The batman would bring the washing down to her. She also used to do all the laying out in the village. She’d know when someone was dying and would say she’d be got up that night to go round and wash and dress the body. She’d put pennies on the eyes to hold them shut and she’d tie up the chin if it fell open. She would then tend the body for seven days because in those days it stayed in the house until the funeral

It was also the traditional starting place for many processions marking national events. In its latter years it was owned by Phipps and Co. Brewery (Northampton), and the last landlord was Archie Bushell who moved when the pub closed to the White Hart at Grafton Regis. The Anchor was demolished in 1965 as part of road improvements at the junction of the A5 and the High Street.

and she’d see the body into the coffin. Then she’d help with the funeral tea and she’d get half a crown for doing all that. She’d insist that the body had to look nice and my Dad would say “I don’t know why you do that” and she’d reply “It’s the living that hurt you, the dead will never hurt you.” She didn’t believe in ghosts.

Mum was a wonderful caring person who would always help you if she could; she knew what it was like to be poor. She also used to help the midwife, Nurse Bracken, and the village people would come to her for advice because she’d had so many

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 101

WI ladies outside the village hall on Rose Queen Day, 1938. Left to right: Mrs Jess Bradbury, Mrs Sinclair, Nancy Tarry, Mrs Mary Tapp, Maud Green, Mrs Cowley, Mrs Sue Onan, Mrs Maycock. Seated: Dorothy Pratt. [Milton Keynes Museum]

The Anchor Inn with members of the Pratt family who ran it for many years. [Hilda Faux’s “Memories”]

children. Many a time young girls would come to her when they were pregnant and she’d talk to them about it, she’d always got time. I never knew her sit still. When she sat down she’d peg a mat or something. She dyed all the material herself and she’d sell the mats for half a crown and give the money to the chapel (URC). She loved to sing and she went to the chapel services. She also worked in the house for Mr Whitehouse who was the minister. We had an old gramophone which we used to put on and she’d sing away. She never let you know when she was down.

My Mum used to take her joint of meat and her pudding to the baker’s to cook. She would have a whole leg of lamb and an enormous pudding and it would all be absolutely gorgeous, she took it to Bill Druce’s farm (now Holly House) because he had a bakehouse where they baked bread. Bill Druce used to say he knew which puddings had got too much water in because it was sloppy and came out wet. When people were short of milk they’d make it up with water.

Mum’s hobby was wine making,

she made all sorts and she used to sell it. Even the policeman’s wife used to come and buy it, although it was against the law. She made all sorts of fruit wine, she’d put all the fruit in a bowl, add water and soak it. Then she’d squeeze and strain out all the juice and add the yeast and sugar, and she’d stand it in big stone jars until it was ready to be bottled. They used to come from all over the village to buy it from her.

When Lord Hillingdon was in Wakefield Lodge a group of women from the High Street or Blackwell End would take an old pram up to Wakefield woods. They’d put four stakes, one in each corner, and load it with firewood and the kids would climb on top to be pushed home. Before they left home they’d put the dinner to cook on the range so it would be ready for the menfolk when

Dad’s Army

We are all familiar with the Home Guard through the antics of “Dad’s Army” on television. It was created so that men who were either above or below service age could make their contribution by being ready to repel the invaders should they ever arrive. Potterspury had its own branch as did Yardley Gobion, and here, Doug Holloway remembers some of the lighter moments!

Bert Tapp (later to become Mayor of Milton Keynes) was a younger member of the Home Guard. During one exercise he was “escaping” from his colleagues and asked Syd Holloway whether he could hide in the attic at 78 High Street. Given permission, he clambered up through the trap door. The roof space in these houses was open to all four in the block. As Bert went along he put his foot through Arthur Kingston’s ceiling at no. 74. It is not recorded whether Togo Webb, who was in charge, remarked, “Stupid boy!”

During the war, the Holloway brothers (Syd, Dick and Ken) kept pigs and would regularly go round the village collecting kitchen scraps in some old 40 gallon

oil drums on a hand trolley. One day some of the Home Guard were given the task of “defending” Potterspury House from the rest of the platoon. Syd Holloway turned up with his oil drums on the trolley with “attackers” duly hidden inside them. The defenders said, “Whup Syd” (a traditional Pury greeting), allowing him free access to go in and The Mansion was duly captured! Shades of the wooden horse of Troy!

Potterspury platoon had a wooden hut on the top of the church tower as a lookout post. One day Yardley Gobion Home Guard were to “capture” Potterspury. The Pury platoon were keeping their eyes peeled looking across the fields towards Yardley from their vantage point. The Yardley men marched off via Moor End, Wakefield and Puxley and came in and “captured” Pury from the other direction. Pury said, “It weren’t fair!” At the end of the war, instead of lowering the lookout post to the ground it was unceremoniously thrown off the tower. (No doubt in the television series the warden would have been walking past at the time.)

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 102

A view of Church End from the Church tower in the late 1930s. [Milton Keynes Museum]

they came home. They did this five days a week.

Leon’s father [Leon is Joan’s husband] used to entertain when I was a child, he could play any instrument and he was a wonderful magician. He’d have his pockets bulging with pocket tricks with which he’d entertain everyone in the pub. He often entertained at the village hall and I once went to a British Legion Christmas ‘do’ at the village hall and he asked us children what we’d really like; would we like books or cakes or

Gun Law

Beryl Gibbard and Keith Solesbury recall Charlie Webster (Blowie we used to call him) having a .22 rifle, and it used to worry his mother to death. He used to go shooting squirrels. Sergeant Ostle (the village bobby) went down to the Reindeer one day when Blowie was in there. “Come on Charlie” he said, “I know you’ve got that rifle –where is it?” Blowie replied, “No I ain’t”. Ostle went outside and after 5 minutes came back in and said “Alright, Charlie, I’ve been to see your Mum – she told me you’ve got it.” Blowie said, “What the bloody hell she doing, tellin’ you that.” Blowie got fined about £2 for having a rifle. Ostle had had him as easy as that – he’d only stood outside!

sweets? Of course we all shouted “sweets” and he just produced all these sweets out of an empty canister and I thought to myself, “Aren’t that man’s children lucky; they’ve got a father who can produce sweets out of nowhere.” Visiting concert parties used to perform in the maltings behind the Reindeer and they’d stay for three weeks. Strudwick’s Fair used to come to the field in Blackwell End and Mum would find a couple of pennies for us to spend there, which must have been very hard for her. We used to be sent to chapel on Sunday morning, afternoon and evening, but in the afternoon we’d go for sweets to Aunt Lil’s shop. We were allowed a halfpenny worth each which would go on the book. We’d buy something that would last a long time or a halfpenny bag of all the bottoms of the jars.

When I was young I spent all my time with my Mum, we were very close because I only went to school for six months of the year during the winter [Joan has a chronic hereditary skin condition]. In the summer I’d spend between six weeks and three months in Northampton General Hospital every year up until I was 14. Actually I never minded, but when I left school there was no work for people like me with a disability so I never worked. My Mum used to work as a cook at the Old Talbot, so I used to help in the house and do things for her, so she gave me ten shillings a week. Out of that I’d go to the pictures at the Scala in Stony Stratford; the fare on the bus was

The Old Talbot Inn

The Old Talbot is one of the village’s original pubs, a former coaching inn, dating from the 18th century. It was formerly a Hopcroft and Norris (Brackley) pub, taken over by the Northampton Brewery Company. It was expanded in the late 1960s, having a restaurant added. Maurice Coles was landlord for several years and built up a good restaurant trade. After his retirement the pub had a series of managers before being sold by Watney Mann to the Hungry Horse chain. It still serves as a ‘local’ for some villagers, and today the large screen satellite TV is a particular attraction on the days of major sporting occasions.

seven pence return, the pictures, a shilling, I’d pay half a crown a week into a clothing club and I smoked 20 cigarettes a week. I did that until I was married at 20.

When Leon and I got married we had nowhere to live so we moved out of the village for a few years. Our son, David, was about two and a half when we came back and we had nowhere to go then, so Leon went to live with his Mum; David and I lived with my Mum in Blackwell End. Leon used to walk the villages to try and find us somewhere to live, he went to all the farms and to the council and in the end they gave us a little condemned cottage behind the Anchor pub. It had three rooms, one on top of the other, and a wash house out the back with electricity downstairs but nowhere else. It had an old grate with an oven and a primus stove and we had to fetch buckets of water. I had to push the red embers under the oven and I had a hook above for the kettle. You couldn’t bake cakes because you couldn’t trust the temperature of the oven. We moved to a brand new house in Blackwell End when David

VILLAGE LIFE AND VILLAGE PEOPLE 103

A British Legion Christmas dinner in the village hall.

[Source: Mrs Gladys Barby]

was eight at a rent of 18 shillings and ten pence a week.

I used to sing. There were four of us: Terry Tapp, my sister in law, Ann Sharp, my friend, Paula Summers, and myself, and we went along to be in the Henry Fermor concert. We used to go to practice every week with Henry, it was good for a laugh. Henry was in service in London and his Mum used to live in one of the cottages on the A5 by Soper’s farm. When he retired he came back to live here, he was a female impersonator, but in those days the villagers didn’t understand things like that so they used to laugh at him. He wore all this make-up and had big hats with beautiful ostrich feathers, he also had some lovely dresses which must have cost the earth. At one time I had to sing “They try to tell us we’re too young” with two of the village kids sitting on a bench canoodling and I was supposed to split them up. I wore a red chiffon dress covered in sequins, and red shoes. We also sang in the chorus but one night poor Henry stepped back too far and fell off the back of the stage and disappeared. Everyone just screamed with laughter, but he was a real trouper, he struggled back and carried on, he was a lovely man.

Let us return to memories of childhood in the village through a

girl’s eyes during the post-war years. Ann Daniells recounts her early years growing up in the village. Since then, Ann moved away but returned to live in the village in 1998.

A girl’s memories of the post-war years

Ann Daniells

In the forties, day-to-day life was totally within the village, and every side of life, school, church, shops, had its seasons. We lived in Grafton Terrace.

Games were played by season. We would have skipping with a thick

rope stretched across the street, with one child at each end twirling whilst everyone else skipped to the song, “All in together this fine weather”. The High Street was the main playground outside of school, and in those days there were no parked cars! There were some cars in the village, but you could count them on one hand. We played with whips and tops which were carefully coloured with chalk so they made a pretty pattern when they spun. Then we chalked out hopscotch on the pavement, and threw a piece of slate into each square, before hopping off and picking up the slate whilst balancing on one leg. During winter evenings we played 60-in: one of us counted up to 60 whilst everyone else went off to hide.

We played ‘two balls’ on Johnny Wise’s brick wall and of course people were not too happy with us if the ball ended up in their beautifully kept front gardens. Johnny Wise lived with his sister Florrie, and although they had a big house, they lived in the cellar. He had a terrible temper, and he used to shout at his sister. We used to peep into the cellar, which was lit with a paraffin lamp. Johnny would go to Stony Stratford and Wolverton on his bike, and sell rhubarb, apples and bluebells from his garden. People in the towns thought he was very poor. What they didn’t know was that once a year out would come his car, he would wear a

POTTERSPURY THE STORY OF A VILLAGE AND ITS PEOPLE 104

Entertainment with Henry Fermor (the clown).

[Source: Jack Clamp]

Performers in a Henry Fermor concert of the early 1950s. [Source: Jenny Walker]

bowler hat, gold watch and chain, and drive to London to his old school, the Blue Coat School, where (I think) he was a governor.

The weekly entertainment was Camera Jack who used to show Laurel and Hardy films in the village hall, then called ‘The Hut’. Only two or three people had televisions in those days. The Brownie pack used to meet in the Old Social Room. I remember having to draw a picture of something that we would like to give to the then Princess Elizabeth for her 21st birthday. When we got a bit older we went to Girl Guides, which met on a Thursday evening. Miss Faux was our

Guide Captain, and we played games, learnt our knots, and worked for our proficiency badges.

On Good Friday we would go to the woods to gather primroses and violets, and on Easter Saturday we’d take them to church to decorate the children’s corner where Miss Hilda Faux would supervise the Easter Garden. On May Day, we would collect wild and garden flowers, decorate our dolls’ prams and go around the houses singing, “Good morning, good ladies, good morning we say, for we’ve come to remind you all it’s the merry month of May”.

Most of our mothers were at home, as very few went out to work, but some took in washing or dress making. Washday took some organising. Mother was up very early to light the copper, which was in the wash house by the barn, quite a way from the house. There was a big mangle to squeeze out water from the washing before hanging it out to dry. Some people who took in washing or had large families were still busy washing away by candlelight to get finished.

On Sunday afternoon I would go to Sunday school, where we were awarded with a stamp each week for good attendance. After that we would go for a Sunday walk around Puxley or in summer we’d go further

afield to Bradlem Pond or the Queen’s Oak. We would have on our Sunday-best clothes and I remember I had a blue straw bonnet with pink rosebuds. Whit Sunday was something to look forward to as we always had a new dress and could wear ankle socks, which made a great change from lisle stockings or woollen knee socks.