by Sydney Pearson Illustrated by angelina so Instagram: @ang_i_i_

In the glow of a mid-February twilight, as falling snow dusted the lining of my coat, I walked on water.

I was on a trip with my Christian fellowship, enjoying a weekend of singalongs, talks, and games in the woods of eastern Connecticut. During the afternoon of the second day, several friends convinced me to explore the frozen lake below the retreat center. I was wary—the ice seemed slick and merciless. I had read Little Women as a child; there was no way I was going to risk hypothermia by crashing through the ice a-laAmy March.

Despite my qualms, my friends reassured me; lots of people on the retreat had already traversed the lake and made it to the island in the distance with no problems. And while exploring earlier, they had met an ice fisherman who showed them how thick the

I’ve never considered myself a creative type. I long for structure and neatly-within-the-box thinking, despite my best efforts to create something wholly original. Though this preference has always made it challenging for me to adopt a creative hobby, I recently found an exception—an outlet grounded in precision with room for experimentation: cooking. I admittedly haven’t had much direct experience in the kitchen beyond Cooking Mama on my DSi. My mother, bless her heart, is a wonderful cook, but is staunchly anti-measurements and instructions. We can’t help but laugh as I try to convert her “cucharaditas” and “tilíns” and “chorritos” into measurable quantities over the phone. I suppose that’s where the creativity comes in—filling in the gaps to prevent these dishes from getting lost in translation.

Our writers this week are also looking inward and feeling inspired. In Feature, Sydney processes her fears

sheet was. A car can drive across it , he said. Eventually, semi-convinced, I agreed to go out, wondering if I was about to make an awful decision. Finally, I steeled my nerves, lifted my boot off the shore, and placed it on the ice.

***

For the past three years, I’ve attended the same fellowship retreat at the same camp every February. As I’ve returned year after year, the woods and the mess hall and the lake stretching out into the distance have become familiar to me. While I spend no more than 48 hours there every year, I feel that I know this place—the smell of the cabins, the trail that leads to a beaver dam, the white metal cross standing sentinel over the leaf-strewn fire pit.

Yet, despite how much stays the same, the camp still changes every year. During my first retreat, it was sunny and dry outside. Dead leaves covered the ground, and at night we laid on the lake’s dock, staring up at the stars. The water was bright blue, and I sat in silence one morning, watching a seagull bob on the waves.

The next year, the trails were covered in snow. I hadn’t thought to bring boots, so I crunched through the drifts in my sneakers,

about the future as she traverses a frozen lake, while Ellyse meditates on the fragility of maintaining equilibrium. In post-pourri, Rchin contemplates consciousness upon building a snowman. For two of our writers, home is where the heart is. In Narrative, Ben describes the evolution of his relationship with his home in Connecticut as he’s acclimated to life in Rhode Island. Meanwhile in A&C, Alyssa explains how growing up in New Jersey cultivated her thrill-seeking behavior, and how this is reinforced by the band Bleachers’ fast-paced music. As for our other A&C piece, Chelsea talks about The People and how this play inspired her to write about social issues. Our remaining three pieces are best described as odes to creation. In Narrative, Sarah begins making flower arrangements in light of her grandmother’s passing. And in Lifestyle, Katherine reflects on her time at Brown through the process of making kombucha, while Gabi shares with us her love of crafting and knitting. As a delightfully fitting end to this issue, make sure to do the post-themed crossword puzzle

toes growing numb from the cold. Patches of ice floated in the shallows of the lake, but the skies were mostly clear, streaked with clouds and glowing pale at sunset.

During this final year, the camp was overcast, and the lake stood still and imposing. Ice coated the gravel parking lot, and my footsteps were loud, echoing as I broke through frozen snow while walking through the trees. I found the same rock where I had sat watching the seagull two years prior. I remembered how the water had once lapped at the shore, babbling and sweet. But now the lake spoke in a deeper voice, calling out from beneath the ice. Every few minutes, it would groan and bubble, as if some massive force was trying to burst free from its charcoal depths.

Though singing ice was new to me as a born and raised Californian, it’s not uncommon for ice to respond loudly to temperature changes. John A. Downing describes ice as a type of drum: a surface that quakes when impacted. When the outside air or water below the sheet heats up or cools down, the ice will expand or contract respectively, leading to strange creaking noises. While the lake in Connecticut was relatively quiet, others

by Ishan!

Don’t get me wrong, I know I can always fall back on NYT Cooking for recipes like lemony garlicky miso gochujang brown butter gnocchi and Marry Me Chicken—which I’ve made one too many times for it to be subtle hint-dropping. But if I truly want to keep my culture alive, if I want to share every meal with my parents (even from afar), I must take a page out of my mom’s recipe-less book and develop my own culinary intuition. And while that’s daunting for an amateur chef like me, I’m excited to harness my creativity—to trust my gut. I implore you to do the same, dear Readers, and see where your instincts take you. Take the paths less traveled by and pave some new ones along the way. And if they just so happen to lead you to our latest issue of post-, then you’ll know it was meant to be.

With a dash & sprinkle & pinch of love,

Katheryne Gonzalez Narrative Managing Editor

could sound like lasers, pinging and echoing beneath their smooth, deep surfaces.

As the five of us ventured out on the lake, I was cognizant of all the risks in front of me. I avoided anything that looked remotely like a crack, and I shuffled slowly to avoid slipping and breaking one of my precious bones. We stopped frequently, taking pictures and creating snow angels in the fresh powder. I raised my head and let the falling snow touch my face, trying to taste the flakes on my tongue.

As I looked out across the surface, I remembered the Biblical description of the throne room of God in Revelation 4:6. Something like a sea of glass, similar to crystal, was also before the throne. In the blue air, I thought about Heaven, images of fields stretching out to the horizon, songs rising all through the night. A world of safety, peace, and life never-ending. But still, my fears remained.

Dying on a frozen lake is only one of the things I’m afraid of. Bicycles. Hurting people. Expired pasta salad. Forgetting the past. So much scares me. What will happen in the unknown of tomorrow? Will I survive if I take a leap of faith, try something new, and fail?

As my future beyond Brown begins to loom large, I’ve seen my fears intensify. The world away from the hills of Providence feels like a blank canvas: an empty, seamless room. What will happen once I leave this place? Will my friendships remain? Will I continue to find joy and beauty? Or will I slip and fall, crashing through the ice?

The shore receding, I grew more confident in my ability to traverse the lake. Soon enough, I longed to go faster and faster to cover as much of the surface as possible. I wanted to see where the fisherman had drilled his hole. I wanted to touch the craggy island in the center that had once seemed like another world. For the first time, I wished I knew how to skate so I could cut across the ice, swift and sure as a bird in flight.

As I continued walking, one of my friends dragged her boot through the snow until the bubbly gray surface appeared. She pushed off and glided across the track as if riding a skateboard.

“Sydney, come try,” she called out. I

shook my head, held in place by my fear of falling. She had me hold her hands and pull so we could skate toward one another across the track. But when we tried, she slid smoothly while my boots barely moved an inch. I was still too scared to let go.

***

Over and over, fear has choked me, holding me back. I’ve avoided events, stressed that everyone secretly hates me. I’ve refused to share what I believe, worried I’ll be judged. Even the smallest decisions, like my running routes or where I sit in the Ratty, are based on fear. It’s not uncommon or bad to be scared. Fear has an evolutionary purpose; it’s the instinct that has helped the human race survive for thousands of years. But sometimes the worry feels stifling, and the lengths to which I’ll go to avoid it ridiculous.

I’ve even tried to run from my fear of the future. I don’t like to talk about what comes after graduation. I shut down when my parents bring up something as simple as my summer plans or apartment hunting. It just makes me think about life beyond this place, a boundless space with so many risks and trials. I know there’s goodness out there, somewhere amid the vast, icy landscape. But what if I can’t access it?

***

Earlier in the day, before traversing the lake, our speaker for the weekend gave a sermon. As he talked about the love and forgiveness of God, I spotted a flash outside the wall of windows in the front of the room. There, soaring above the lake, were enormous brown wings, sharp yellow claws, and a pure white tail and head feathers: A bald eagle, hunting and nesting in the woods on the shore. As I watched it fly, I wanted to ask where it was going. Bald eagles subsist primarily on fish. In a world of ice, what could possibly be out there? And even if a hunting hole appeared on the surface, were any fish still alive? How could anything survive in such emptiness and cold?

But life finds a way. When food supplies are low and fish are difficult to access, bald eagles will eat anything they can get their claws on; waterfowl, squirrels, even garbage. And as lakes freeze over, freshwater fish go into a semi-hibernation called “winter rest” where they settle into deeper pools filled with warmer water. As the season marches on, fish metabolisms slow, allowing the

creatures to consume less oxygen and food until the world thaws. Animals are adaptable in that way. They know the world will not end with ice.

***

Eventually, we turned back from our walk across the lake, having been called in for dinner. I shuffled back to shore, then climbed up the hill and into the mess hall, my glasses steaming with the sudden heat. I never made it to the island. And now I never will.

The next morning, a few hours before leaving the camp, everyone on the trip stood in a circle and sang together, arms across each other’s shoulders. I looked around the room, at every person I love so fiercely, and I teared up. I don’t want to leave these things behind for the unknown. I don’t want to risk slipping and falling.

But I know when I don’t take that step offshore, I risk missing out on joy, the fierce, beating type. I miss climbing on islands and snow coating my braids and dancing with friends in the dying winter light. The ice can be terrifying, cold and slick and groaning. Yet there is life to be found, warm waters to rest in, and food to find. The surface won’t break beneath me.

As I finish up my final feature for post, I’ve been reflecting on endings and fear, especially as I revisit the concepts from my first article two years ago. There, I discussed my yearly dread around my birthday; anxieties about my own unworthiness, the nagging suspicion that everything would somehow fall apart on a day that’s meant to be perfect. I was scared of my birthday because, in many ways, I feared the future. What if nothing went as planned? What if there was no joy waiting for me when the day finally arrived? But despite my qualms, my 20th birthday was wonderful. Things have a funny way of working out, I guess.

I bring all of this up because, in a strange twist of fate, this last piece will be published on my 22nd birthday. It is an occasion I once dreaded, but one I finally feel mildly excited for. I still do not know exactly what will happen on that day, and the concept of aging remains immensely daunting. But I know now that I’m no longer afraid of my birthday. There will be goodness ahead, I’m sure of it. So maybe, just maybe, I don’t have to fear the future beyond Brown, either. I just have to trust in the ice, take the first step, and glide.

“Has anyone done a bit that’s just Goldilocks and her three bears, but it’s three gay guys?”

“I bet Portland does have Subarus and it’s probably because of the lesbians, not the other way around.”

by Ellyse Givens

Illustrated by Ruby Nemeroff

1. In game theory, players are assumed to be rational actors, meaning they make the “move” that best benefits them given the choices of other players. That’s why, in economics classes, you draw tree diagrams, starting at the very end and working backward, allowing players to evaluate every future possibility before determining their decision-making in the beginning. These repeated games sometimes result in a Nash equilibrium, defined by John Nash as a stable outcome in which no player can improve their position or increase their payoff by changing their strategy. In other cases, though, players continuously adjust their moves based on the previous actions of others, creating a repeating loop of “tit-fortat” where they never settle on an optimal agreement.

2. My friends and I climb the stairs of a Boston bar called Arya. On the walls are photos of the restaurant owner with various

celebrities. I stumble slightly around the turn—my ballet flats and two glasses of wine make me clumsy—spotting a younger Dwayne Johnson hanging in the corner. Then, a Paloma and me at the end of our mahogany table, I make myself concentrate on the candle (there’s fresh snow on the tops of my bare feet, and I don’t think I’ll ever get used to how frozen things scald in their own red-hot way). A tells us about T.

“I think, before my relationship happened, I became so tired of men that didn’t care about me,” A says, his chin tucked into the heels of his palms. “It got to the point where all I wanted was someone to care about me.” I watch the little flame jump. “Attraction wasn’t as important. And now I am back to only caring if they’re hot and not as much about how they treat me. It’s like some pendulum, going back and forth,” he says.

“Really hot and don’t treat you well versus treat you well and not as hot,” I summarize, imagining those county fair pirate ship rides that swing up and back down an imaginary half pipe.

I think about Y and how I needed him and those feelings at 19. How, today, I don’t want anything like it. Perhaps I will again soon. I see A’s pendulum and wonder if it will all slow down at one point, if I will swing in smaller and smaller “U’s” until one extreme doesn’t incite the pursuit of the other, until there’s no energy left, and I come to rest.

3. The vestibular system, comprising the balancing organs, is located in your inner ear. Three fluid-filled loops respond to head movements: the superior canal for up-and-down motions, the horizontal for left-to-right shaking, and the posterior for tilts side-to-side. Two sac-like otolith organs are located just below—the saccule, which

detects acceleration in the vertical plane, and the utricle in the horizontal plane. When balancing, your brain takes in information from these five organs, as well as the eyes and the joints, and sends it to other organs, allowing us to adjust to where our body is in space.

4. I used to say that Y taught me how to relax—that he balanced me. Sitting opposite each other on a seesaw, he straightened me out, as if he carried just the right amount of rocks in his pockets.

One night in a London club called Cuckoo, Y’s best friend Z leaned over and told me, “Y really loves you.”

I was drunk at the time so I believed it. But I’m not saying that Z was wrong.

5. I used to think about wanting my younger self to know Y. She would be astounded to know she could be this loved, I wrote last February in a journal I bought from a stationery store. I think I did feel this, albeit in a weird and Jungian-esque innerchild way.

6. One time, I popped my ears really hard, plugging my nose with a thumb and a pointer finger and blowing. I must have been sick at the time. My room started to turn, just a bit, and then suddenly it was upside down, warped. I stumbled into my mother’s office, sat on the carpet, and vomited into a beach towel.

7. This spinning sensation is called vertigo. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), the most common cause of vertigo in adults, occurs when the tiny calcium crystals come loose from their normal location within the utricle, allowing them to flow freely into fluid-filled spaces of the inner ear.

8. In March, I wrote: What will I do when Y dies?

(Y always said it was weird that I thought about death.)

I feel like he is my lifeline. What do I do if I’m not his?

9. Although equilibrium is a state of balance, it does not necessarily imply “equality” in the sense of identical quantity or value. In chemistry, equilibrium is reached when the forward and reverse reaction rates are balanced, meaning the system will remain stable over time without further net change. But this doesn’t mean that the actual amounts of things in the system are the same—in fact, only a very small percentage of chemical equilibria will involve equal quantities of reactants and products on each side of the equation. Only some isomerization reactions are perfectly balanced in this way.

Similarly, when a Nash equilibrium is achieved, players’ gains are not necessarily balanced or equal—only settled in a way that

leaves no one with a better alternative, even if fundamentally uneven. But this was not always the case. Before John Nash came John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, who first developed the concept of a game theory equilibrium. Their definition of equilibrium was solely for the special case of “two-person zero-sum games,” in which one person’s gain is always another’s loss; the payoffs always sum to zero. Nash proposed an expanded notion of equilibrium that applied to a much wider class of games, including those with different payoff structures.

10. When I broke up with Y, I told my therapist I wasn’t mourning him. I said, “I’m mourning who I was when I loved him”—a woman-child certain of her own incompleteness.

11. My fifth-grade teacher said that 11 was the best age to be. On my 11th birthday, she drew two number ones with the thick edge of a green whiteboard marker. “At 11, you have one foot in your childhood,” she said, pointing to the first. “And then the other half of you has entered the older numbers—your adulthood. You have the best of both.”

This teacher and I had the same birthday, January 11, which made me feel special. But I always wished I was born in 2001 so that I would be even, 01/11/01—you could draw a line down the middle of the date and have the same thing on both sides.

I have always cried on my birthday, maybe because it reminds me of my asymmetrical origins. Or maybe because it always feels like I’m standing in two places at once.

12. From Central London, I take the Jubilee Line to North Greenwich, the nearest tube station to Greenwich Park. At the park’s highest point is the Royal Observatory, through which the “prime” meridian passes, splitting the Earth into the Eastern and Western Hemispheres at 0° longitude. I try walking into the observatory, just right through the gates. “Adult tickets are 24 pounds, miss,” a staff member stops me. I apologize and begin to turn around.

“Did you want to see the prime meridian?”

I look back at him.

“Because if that’s all, I can show you.”

He walks me down a steep path running along the edge of the observatory gates, all the way to a thick bronze strip in the ground. Carved faintly above it on the rock wall is:

GREENWICH MERIDIAN East Longitude | West Longitude

I look up and see people’s shoes on the gated balcony, realizing (quite dumbly) that the actual meridian isn’t confined to the observatory’s display. I thank the man and put my back to the wall, placing one foot on each side of the line, straddling east and west for free.

13. It turns out that, unlike latitude, which is measured from the equator, the designation of the prime meridian (0º longitude) in Greenwich was completely arbitrary. As international travel increased in the 19th century, the need for a standardized global map system became clear. An 1884 conference of 25 nations chose the Greenwich Meridian as the “prime” meridian, mainly because of Britain’s dominance in maritime navigation at the time. France disagreed and continued using its own meridian through Paris for another 30 years.

In the 1980s, the International Reference Meridian (IRM) established the precise location of 0° longitude. With satellite technology, scientists realized that this point is not a fixed location, and will continue to move as the Earth’s surface shifts. Currently, it is about 334 feet east of the prime meridian paid exhibit in Greenwich Park.

14. “The child motif represents not only something that existed in the distant past but also something that exists now …a system functioning in the present whose purpose is to compensate or correct, in a meaningful manner, the inevitable one-sidedness and extravagances of the conscious mind.” (Carl Jung, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 1969)

15. They say relationships shouldn’t complete you. But doesn’t it feel really good when they do?

16. Asymmetrical balance in art refers to the “comfortable” feeling you get from a piece that is not necessarily symmetrical, but still feels balanced. For instance, bright colors are visually heavier than dull colors. If something is large and dull, something small and neon could match its perceived “weight” despite being objectively smaller.

17. In balancing yoga poses like Vrksasana or “Tree,” I am told to find a Drishti —some steady point like the tip of my nose or a groove in the baseboard. When you stand on one leg, new information from the vestibular system is always being processed by the brain, spurring slight but continuous adjustments in muscle activation—really, we are never still. The Drishtis must laugh at our will to be.

18. All velocities are relative, meaning they are measured with respect to some reference frame. Because of this, no object in our universe is truly still; it rests only relative to a given frame of reference.

19. In his Principia , Newton writes, “It is possible, that in the remote regions of the fixed stars, or perhaps far beyond them, there may be some body absolutely at rest.”

20. Maybe balance is just a feeling. Something we tell ourselves.

21. Something in the stars. Or in us.

22. It is midnight on my twenty-second birthday, and I weep.

by Benjamin Herdeg Illustrated by Rosa Zha Instagram: @zrgzzzz

At the start of school, everyone said they had moved out of their homes when they came to Rhode Island. I didn't move much. Two suitcases: a few sweaters, sheets, New Balances, a bottle of wine that was finished in a week. Toiletries. My home was in Connecticut. It was close, so close I didn't bring much. I didn't really move.

The first time I went home was for my cousin's wedding. She married her Hinge boyfriend on my aunt's farm in Pennsylvania. Dinner smelled like horse manure. I slept in my own bed at home the night before. Then my dad drove me to the ceremony, past sorghum and fields of trees that were once farmland. My dad performed the ceremony, as he knew the most about our religion. The next day, he dropped me in Delaware so I could take the train back to Rhode Island.

After that first visit home, I grew more convinced that Rhode Island was different from Connecticut. License plates. Cannabis laws. An accent that approached the throatiness of Boston's. I thought if I could live in one state, it would be Rhode Island. I thought if one state could change me, it would be this one. I thought staying young in this state meant supplementing memories of sweaters, wine, and sneakers in Connecticut. So I went accumulating. I went making memories.

I traveled home for Christmas and no one understood me. My sister asked why she saw my underwear above the waistband of my Levi's. My mother commented on my laugh, steadier and lower than before. My dad still lived in the past— bifocaled, boat-shoed, bourboned with a floating hunk of unmelting ice. He asked what I thought of Rhode Island. He hid a gift for me below the tree: a nice, durable suitcase.

I brought more with me the second semester.

I learned I had more to take from home, so I put it all in Rhode Island. A family photo with a frame around it. A shoebox of letters I had received at summer camp. An ergonomic chair with wheels. I learned my way around my new city, my new state, Boston, the Cape. I rode the bus when I could, made friends where I found them. Called home when I had the time.

I went home only once that semester, and it was for my grandmother's funeral. Back in Pennsylvania, I was again at my dad's childhood home. He's from that farm. He dresses now like his dad did before—my grandfather's dead, like my grandmother is now—but my dad keeps on. He says there was a time when you could tool along the interstate, one hand on the wheel, one gripping a chilled Heineken. Everyone had convertibles. Everyone listened to the same music. All music was happy or about love.

At graveside, my aunt gave me a charm necklace with a St. Christopher medal—the saint of motorists and travelers. When I was back in Rhode Island, I started to pray with it at my bedside. Prayer by prayer for my family, I signed my soul over to a new state, and I began to miss it over there—Connecticut—which wasn't all that far, and with each thought of it I'd miss it more, and it felt farther. In all the time between visits, I collected. Memories, ideas, things—I gained things. Stuff that may never see or know a home.

That summer my room became a storage unit for my life away. I configured it—the stuff—in a way that made it easiest to pack everything up and ride back along the coast to Rhode Island. What had been time away became time on. What had been a return home became a departure. Even when I was in my Connecticut house, I didn't spend much time in my Connecticut room. I started to fear what I had been afraid of before: monsters under my bed, skeletons in my closet. I felt smaller. I spent most of my time at the kitchen table, seated between my parents.

Within a week of the service, we took my grandmother's dogs. Now we had three. My dad loved to look at them. I couldn't—and it wasn't for

loss or love or defeat. I only saw myself separating from them. I've barely laid a hand on them.

I am moving out. I speak with my sister over the phone: we parse the words of our parents; we perform a postmortem of our Connecticut lives. The cause of death is bags. I've got so many. Indian to-go food totes we held onto. Canvas beach bags I took from the garage. Those flimsy blue and yellow things from Ikea. I've kept hauling things up here so all I’ve got are bags and so much stuff here in Rhode Island. I care to bring less and less back to Connecticut. There's less that brings me back, and "back" is increasingly nowhere the more stuff I move.

I've gone to Connecticut nine times since moving out. Each time I've traveled, I've noticed something new. A new stop on the Amtrak. I've stepped briefly onto uncharted station platforms just to see how they feel: Kingston. Mystic. New London, the submarine capital of the world. New Haven—I-95 follows a bridge above it that shines a different color every time I cross it. Red then blue then green. Southbound. I drive because I have a car now and it's easier. A rest stop on the freeway—how my new friends from California call it—the highway in Madison, Connecticut. I stop and pee and grab a two-dollar coffee. My teeth turn yellow. I speak less and less like someone from here, now more like someone who left. I pay tolls by simply driving through. Traffic halts and accelerates and then I'm alone and occupy the roads myself. Left lane speeding. The trip takes two and a half hours, but I do it in two. I pump gas—it goes quick when you go fast. I talk on the phone with friends I leave behind as I head home. I send my family an ETA. I make plans for when I'm back.

Connecticut extends the more I see. And home on the western end feels further the more I know in between.

In the trunk I put my nice suitcase. Just a change of clothes and a toothbrush. I am set for the night. I walk through my front door, and my dad is battling our dogs' eyes with his own. They're on the floor like forgotten toys.

by Sarah Frank Illustrated by Dinah Biga INSTAGRAM @dinah.draws

I don’t believe in signs, but then again maybe I do.

On Tuesday, my grandma passed away. I got the call while sitting cross-legged on a friend’s couch, entranced by The Bachelor. The news didn’t come out of nowhere: She’d been in hospice for months, she hadn’t left her bed in a long time, she was no longer talking. So I shouldn’t have been surprised, and I suppose I wasn’t, but you don’t have to be surprised to be sad. I cried a little, but tried to hold my head up.

On Wednesday, I wore a shirt with a vase of flowers on it, determined to do small things to remember her. She loved flower arranging, and she was good at it. You could say she had a green thumb, but we liked to joke that she had “one and a half green thumbs.” Her right thumb was a nub burned off in a fire, decades ago.

I bundled up for the cold, still wearing my flower shirt underneath. After driving to an event downtown, I pulled into the parking lot of the building and looked at the sky, rich with the sunset. It was bubblegum pink, sparkly from the rain. I couldn’t help but think my grandma Mimi would have loved to see it. She liked pretty things. I started crying and it felt nice, and then it felt weird that it felt so nice. My playlist pulled up the perfect song to dig into the emotion: “What Was I Made For?” by Billie Eilish. I couldn’t have made a more perfect selection myself. A deep cry was warranted, and this song brought me to a cathartic edge, finally letting emotion seep out of me.

On Thursday, I started feeling sick. They say something about the immune system weakening from sadness. Maybe that’s an urban legend, but I sneezed once and the congestion just stayed.

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday: I laid in bed, thinking about my grandma and life and loss and sunsets and flowers. I made a list of all the things I wanted to remember about her: that she loved flowers, that she always scraped the bottom of the bowl because “there’s always another cookie,” that she had beaded curtains in the doorways of her homes and they sounded like the ocean. I wrote down that she loved to flirt with hot doctors and

play with young kids. She always used to say, “it won’t show on your wedding day” when I got a bruise or a cut, and she loved to watch me and my brother play basketball back when we loved it too. I wrote down everything I could think of as if writing this list would keep her alive.

On Monday, I started feeling better. I managed to get to class and make it through my meetings, but I couldn’t help feeling like the universe was gearing up to throw me another curveball.

On Tuesday, I went to the mailroom to pick up my packages. I had nine—most of which were small pouches of Disney pins I’d bought for myself and my boyfriend. One in particular though, was rather large, book-shaped, and hard. I tried opening it in the classroom, but the crinkling of the packaging was too distracting, so I saved it for after class. The package was bright pink and had “ThriftBooks” written all over it. I had never ordered from them before, but I recognized the brand because my dad bought from them quite frequently.

But wouldn’t he have told me if he sent me a book?

When class ended, I ripped open the packaging, not sure what I expected to see. It caught me by surprise to see The Complete Guide to Flower Arranging emerge from the pink packaging.

First thought: This was sent to someone else and somehow ended up in my mailbox by accident. I flipped over the packaging to check, but it was addressed to me: Sarah Frank, 69 Brown St.

Second thought: Amazon sent me this instead of the Command Strips I ordered. A different kind of accident. My eyes wandered up to the return address though, and it was ThriftBooks. No trace of Amazon.

Third thought, this one said out loud: “Who on earth would send me this?” The only person in my life that would have ever given me a book about flower arranging was Mimi, someone who had never used the Internet and would not have been able to tell you which city I live in, never mind my address. I know she couldn’t have sent it, but it was the only thing that made sense. She was the only person that made sense.

After class, I texted a photo of the book and the packaging to my mom, who had no idea who sent it. Neither did my dad.

Who even has my school address?

This question narrowed down the list, but the following question narrowed it down even more. Who would send me something, but not text me to say they sent it?

No note, no information about the sender, no holiday or celebration to have sent something for.

Who knows me well enough to have my address, but not well enough to text me that they were sending me something? And maybe even more importantly, not well enough to know that I have no interest in flower arranging?

I carried the book back to my dorm and set it aside. Later, when recounting my day to my boyfriend, I flipped open the book for the first time, and like a camera lens zooming in on a subject, I noticed it: one single word, penned in blue ink on the front page.

Irene.

“Oh my God—” I flipped my phone around to show my boyfriend. “My middle name. Her middle name.” I flipped through the rest of the book to see if there were any other words or markings, but there were none. Just pages and pages about the art of flower arranging: bouquets, dried flowers, special occasions, color patterns.

“I need to call my parents. I’ll call you back.” My mind was racing as I fumbled with my phone. Could this really just be a coincidence? A book I never ordered arrived in my mailbox just days after my grandma passed away, inscribed with the middle name we shared.

“Any idea who might have ordered this?” I asked both parents after sharing my update, but neither of them had any idea. We ran through a list of the people who have my address, a relatively short list. My other grandma, but she would have sent me a new copy if she was going to send me a book. My uncle, but he knows I have no interest in this and whenever he sends a gift, it’s a gift card. And both of them would have told me if they’d send something.

“Is it possible for, like, this to have been in the will?” I asked, running low on sensible explanations for this.

“It’s not,” my mom said. “I’ve seen it.”

“ThriftBooks takes a couple weeks to send book orders anyway,” my dad added, “So this was sent before Mimi passed away, not in response to it.”

“That makes it even weirder,” I murmured, flipping through the book again in case I missed something. Who sent me this?

We listed out every person it could be, coming up with no viable explanations. I tried calling ThriftBooks, but it was after business hours.

“I know it makes no sense,” I said, “and I know that she couldn’t have, but I can’t help but feel like Mimi sent this to me.”

Both parents nodded knowingly. I don’t believe in signs. We don’t believe in signs. But maybe I do. Because if there ever was a sign, this would be one. I’ve never had an interest in flower arranging. I’ve never had a green thumb. Yet, maybe this is one thing I can learn from Mimi— or rather, learn for Mimi. Something we can share, regardless of who sent the book. I think she would’ve liked it if I knew how to arrange flowers. I think she would have enjoyed teaching me.

The next morning, as I’m getting ready to call ThriftBooks to ask about the order, I hesitate. Maybe I want this to stay a mystery. I’m sure there’s a perfectly sensible answer as to who sent this and when and why, but maybe I don’t want to know. As long as I don’t know, it can be from her. It can be from a person who never could have sent it.

Maybe I’ll call another day. For now, this book was from her. And I will be learning the art of flower arranging.

is our little while

the best play you’ve never heard of

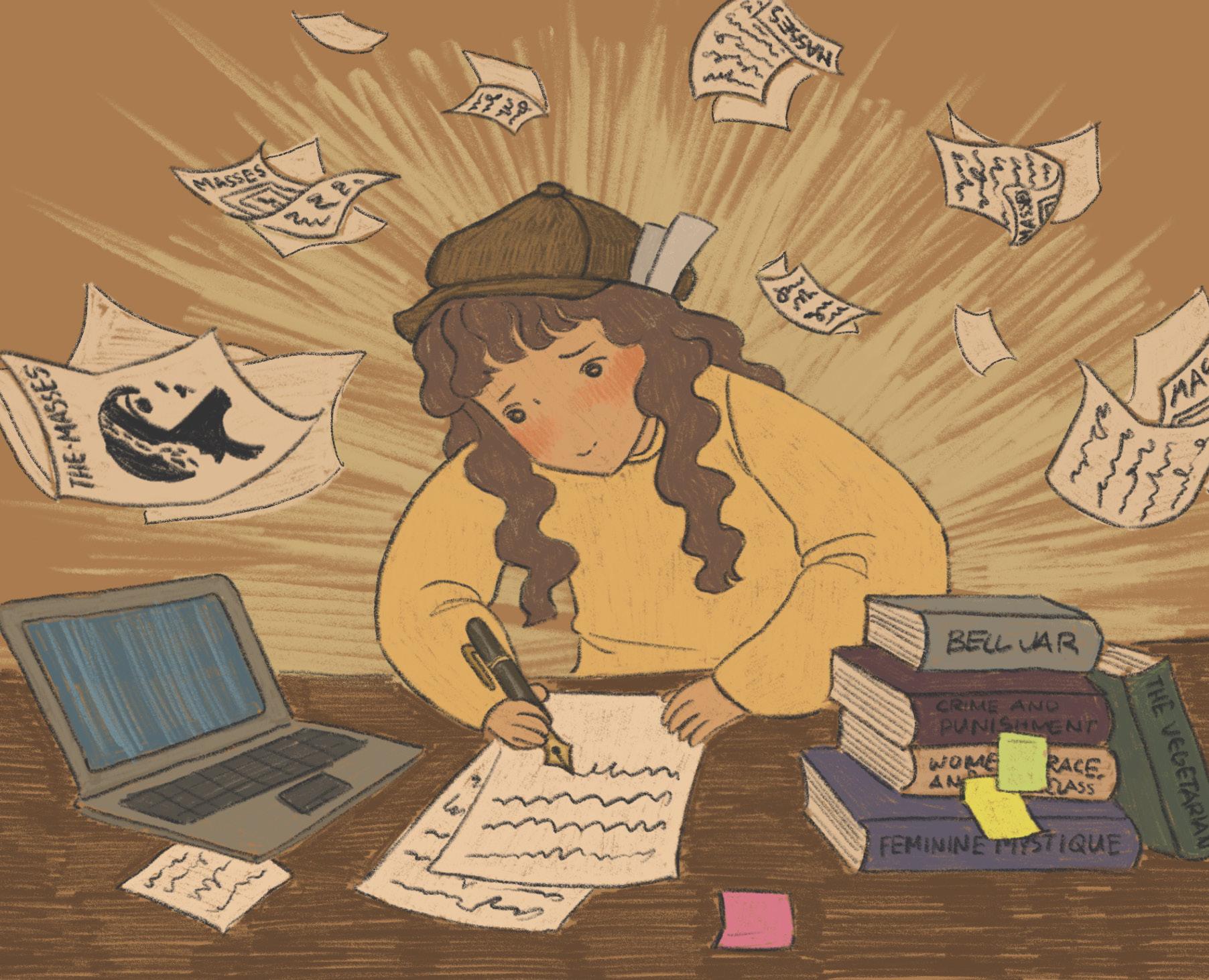

by Chelsea Long

Illustrated by CANDACE PARK

A table, a desk covered with magazines and loose sheets of paper, and posters calling for revolution. These are the set pieces for Susan Glaspell’s one-act play The People, which tells the story of a “radical and poor” newspaper and its staff as they stumble toward a more hopeful future. It’s a comedy. It’s a manifesto. And in 2025, over a hundred years since the play’s opening night in 1917, it’s equally unintelligible and surprisingly relevant.

The play begins with editor-in-chief Edward Wills returning from a cross-country fundraising trip with no money and no faith in the paper’s future. Despite the newspaper’s title, The People: A Journal of the Social Revolution, Ed doesn’t think its articles have contributed to any sort of societal transformation. “Now and then…we have a story that gets a rise out of a few people,” he says, “but— we don’t change anything.”

Ed’s skepticism is challenged when three travelers, each from different corners of the United States, arrive at the office. They’ve all read issues of The People and been inspired by Ed’s words. Ultimately, Ed declares that he’s found “something to go on with,” and The People lives to see another day. Curtains, lights, applause.

Fundamentally, The People is a play about the value of the written word in the bleakest of times. Its characters argue, banter, question the purpose of their work, and make heartfelt declarations about truth and being alive. They speak in simple, beautiful sentences. “We are living now,” one character reads from the newspaper. “No one can tell us we shall live again. This is our little while. This is our chance.”

I’d say The People is a fairly easy read—it’s less than 5,000 words, the language is modern, and thanks to public domain, you can find it for free online—but there are some ways that its meaning gets lost for a 21st century reader. That’s because The People isn’t just a play—it’s Susan Glaspell’s satirization of the 1910s arts scene, in what essentially amounts to an elaborate inside joke.

Glaspell was a founding member of the Provincetown Players, an experimental theater group formed in 1915. Many of the Players were also associated with The Masses, a socialist magazine dedicated to “the interests of the working people.” The Masses was led by editor Max Eastman, who gave frequent lecture tours in California to fundraise for the paper and whose biggest fear, according to his biographer Christoph Irmscher, was that “he might only be talking to himself.”

If that sounds familiar, it’s because Ed Wills is directly based on Eastman. The People is an unsubtle satire of The Masses, down to the nearly identical titles of the two newspapers. And Ed isn’t the only character with a real-life counterpart— sarcastic associate editor Oscar Tripp is a stand-in for The Masses’ Floyd Dell, and his fellow writer Sara is likely based on prolific labor journalist Mary Heaton Vorse. In fact, nearly every character in The People can be connected to a member of The Masses. Glaspell puts her contemporaries under the spotlight’s exacting gaze, revealing their

disagreements and doubts with a level-handed mix of blunt honesty and earnest appreciation for their work. Her satire of The Masses is keen-eyed and meticulous, and all in all, the play is an impressive commentary on the intellectual world of the 1910s.

It’s also completely incomprehensible to a modern reader. The first time I read The People, I had never heard of The Masses or the Provincetown Players, let alone any of their various members parodied in the play. Without the background knowledge, The People comes across as somewhat surrealist, with moments of odd specificity and jokes that don’t quite land. I find the play’s history fascinating—the precision of Glaspell’s analogies, the way much of it has been lost to time. It makes me wonder what other bits of meaning we’re missing, subtle references or sly jokes that only Glaspell’s original audience, sitting in a crowded little room in 1917, would have understood.

I’ve always believed in the power of language— words can save lives, words can transform, words can change minds and unlock boxes—so when I first read The People, I didn’t particularly connect with Ed’s cynical perspective. I liked the play for its evocative speeches and witty dialogue, but I never really considered its overarching questions about what it means to be a writer and whether or not the written word can truly impact the world around us.

That changed during my first semester at Brown. I took two English classes and a literary arts seminar on poetry, which meant I was spending a lot of time thinking about language and writing. At first, I felt happy, delighted, whimsical, splendid, et cetera. I would read on the Main Green or sit by a window annotating papers with my favorite pen, all the while thinking, Look at me! I’m so literary! I’m creative and artistic and brilliant! Hooray!

But as the semester wore on, I started to doubt whether writing was really all that important. This transformation had several causes, including a) realizing that I was, objectively, doing less work than my classmates in STEM fields, b) learning about the intangibility and subjectivity of language in class, c) the natural experience of growing up and questioning previous beliefs, and d) the fear I felt about the future of the world following the November election, along with the knowledge that writing a poem about it wouldn’t make much of a difference.

All of these factors put me in a state of mind quite similar to Ed’s. In one of his monologues, he says there’s “something rather pathetic” about the staff of the paper, calling out to a crowd that never calls back, making grand statements about social change without actually changing anything. That was exactly how I felt—why should I write a poem about climate anxiety or an essay on equal rights instead of going out and doing something that would tangibly contribute to these causes? What was the point?

Over winter break, I found a response to these questions in The People. The show ends with one of the travelers, an unnamed woman from Idaho, explaining to Ed how she felt after reading his article in the paper. “You made us want something we didn’t have,” she says. “I had thoughts not like any thoughts I’d ever had before—your words like a spring breaking through the dry country of my mind.”

This, I think, is what The People is trying to tell its audience about the written word. Yes, it’s intangible. Yes, it’s confusing and abstract and subjective. Yes, being a writer means feeling like no one is listening—but what if someone is? Maybe writing can’t patch the ozone layer or make walls fall down, but what it can do is reach out to other people, make them think, make them feel, make them want a better world.

The People ends on a hopeful note, and I believe Glaspell intended for the play to inspire that same hope in its audience. What she can’t have imagined, though, is that the play would still be inspiring hope over a hundred years in the future. The People, as an enduring text, demonstrates its own ideas about the power of language as a vehicle for human connection and the creation of feeling.

To put it simply, The People is the reason I’m still writing. It gives me hope that the words I write will find someone and transform them, make them feel something new and think differently about our world. If you’ve ever doubted the purpose of writing, the purpose of art, the purpose of standing up and saying what you believe, then I hope Susan Glaspell and I have given you a little more faith in the value of your words. After all—we are living now. Let’s find something to go on with.

by Alyssa Sherry

by Allie Abraham

I’m running down the beach with a girl who’s never seen the Atlantic. The sky is blue and unrelenting. Our hands burn frozen from where we dipped them in the waves. Shockingly cold and when the January wind blows it bites hard into the droplets crystallizing on our fingertips. It’s your first time on the East Coast! I had told her. It’s a rite of passage. Only a few stragglers walk the boardwalk behind us, their hair blowing frenzied. She’s grinning as she looks back at me and sifts through the sand to pick out the fragment of a shell. Sand sticks to her wet fingers like a second skin. Something to remember this by.

Later today I will drop her off at the Newark airport. The place that’s seen me coming and going, and going, and going for my entire life. And I’ll want her to stay.

*

I first discovered the band Bleachers when I was fourteen. The band is fronted by Jack Antonoff: best known for producing culture-defining records like Lorde’s Melodrama and Taylor Swift’s 1989, but to me, best known for growing up about twenty minutes from where I did, and playing his first show in my hometown. At fourteen, I was drowning in the suburbs of North Jersey, dreaming of the day my life would get bigger. Dreaming, also, of the day I’d fall in love. More than anything, I felt out of place in my hometown, and on some level I thought that being in love would make me fit somewhere. With someone. I thought I would finally feel awake.

And when I first heard Bleachers’ “Rollercoaster,” it overflowed with life. It was synthfilled and bright and loud and I could feel it in my chest. From the opening lines, it sucked me into a world where love was magnetic and tumultuous, fast and desperate: “It was summer when I saw your face / looked like a teenage runaway,” “We were shotgun lovers / I’m a shotgun running away,” “It’s a hundred miles an hour on a dirt road running away.”

This is what I wanted. Something that would drive me sick. Something that would wake me up.

*

I am standing on a cliff with a girl who is falling in love with me.

Right now I don’t know this, I’ll only learn it many months later. Right now it is spring break of our freshman year and she is one of my closest friends and she is visiting me in New Jersey for a night. Right now we stand at the overlook in West Orange where you can see the whole Manhattan skyline lit up glittery because, for most people, the best thing about New Jersey is New York. It’s how we got the nickname “the shadow of the city.” As we talk we both look forward as though made anonymous by the city ahead. And as we drive the Garden State Parkway home, I play her a song—

“Wild Heart” by Bleachers, which opens with the line, “They closed the parkway late last night / and as I sat with the echoes of the lies that I told / I felt young, never changed by crooked hearts.” Say, The parkway! That’s where we are. Now you get it, this song is about New Jersey.

A few months later, she tells me how she feels. And I’m happy, I think. Because she’s really important to me. But mainly all I feel is panic. I tell myself that’s how all big and important things are supposed to feel. Like I’m fighting myself to grab at them.

*

New Jersey has made me a lot of things. It made me loud, blunt, impatient. Yelling at people in my hometown driving barely under the speed limit. Passing dawdling people on the sidewalk and glaring back at them to prove a point. Falling in love impulsive and selfish. Doing everything at this frantic, jacked-up speed. Always running away from where I grew up, the way it made me feel small.

So when that girl, the one from the cliff, one of my best friends, asked me out—I felt crazy and sick and elated and scared. And so I said yes.

I thought this was the right way to do things. That throwing myself headfirst into every endeavor, speeding through every moment and tearing through new places like a shot elastic, would finally put some distance between me and New Jersey. Would get me closer to my new life. And more than that, I craved feelings that were huge and all-consuming and drastic. I craved the glittering synth characteristic of Bleachers’ first two albums, which had soundtracked my adolescence in New Jersey and taught me that love should be reckless. Love should be huge and deafening. And in this way, I chased relationships that made me feel such intensely oscillating emotions, each day a pendulum swung from giddiness to agony. Love that was, as I first craved when I was fourteen, a rollercoaster. If it made me feel safe, secure, quiet, I had absolutely no interest in it.

*

I am twenty and that relationship is bleeding out and in eight days it will be over but right now it’s 11:59 p.m. on a Thursday in my sophomore year dorm room. My hair is too long. It’s a bit too warm out to be March. It’s a bit too cold out to be March. And I am watching the clock on my phone, 11:59 p.m. stretching infinite, because in one minute Bleachers will release their fourth studio album, a self-titled work largely focusing on Jack Antonoff’s marriage to actress Margaret Qualley.

As I finish listening to the record at around one in the morning, I have the most traitorous, awful thought: I don’t like it.

This will nag at me for weeks. I loved the

lyricism, but the production drove me crazy. The album was so quiet. So devoid of the loudness and passion and angst and youthfulness that defined their previous work. And instead of being about finding some crazy love or hope or chaos on the Garden State Parkway, which had appealed to me so profoundly as a teenager, suddenly it was about marriage. And being settled down. And this quiet, simple love. In “Ordinary Heaven,” Antonoff sings, “In ordinary heaven / you dance around the apartment / and I just get to be there… just getting to witness you.” My first thought: What if that ordinary heaven gets boring? My second thought: What if I want that ordinary heaven more than anything?

*

Five months later, I’ll move to Denmark, and about two months after that, I’ll meet a girl. She’ll leave her contact solution on my bathroom sink when she stays over and we’ll get cinnamon rolls together in the mornings. One day I’m not feeling well and we sit together all afternoon talking and it might be my favorite day we’ve ever spent together. She makes me tea and orders us takeout. And I start to notice that when I’m with her, for the first time in my life, I don’t feel like I’m rushing ahead to the next moment when one or both of us moves on to the next place and the next person. I breathe easier. I breathe slower.

We leave Copenhagen in December and she comes to New Jersey in January. I take her to the place I grew up hiking. To the lakes that my friends and I drive circles around when we’ve got nothing else to do. I take her to all the touristy spots in New York City and she’s surprised that the Times Square ball is much smaller than it looks on television and I even suggest going to the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree even though I’d never be caught dead there otherwise. And I take her to the Jersey Shore—the place that is so closely intertwined with everything that I am. Full of life and a bit ridiculous. And I think of another song by Bleachers and Bruce Springsteen, “Chinatown,” a song about bringing the person you love from New York City down to the Jersey Shore to show them who you are: “I’ll take you out of the city / honey, right into the shadow / because I want to find tomorrow.”

I love being everything that New Jersey made me. Loud, blunt, impatient. Always in search of big feelings and new places. That didn’t change when I brought her to New Jersey. I still felt all kinds of huge things for her, all bright and glittery just like “Rollercoaster” has always been. But at the same time, suddenly, I had nothing to run from anymore. I felt like I had all the time in the world to wait around and find out what would happen next. “Chinatown” sings, “I want to find tomorrow.” I do too.

by Katherine Mao

Illustrated by Lily Engblom-Stryker

For the past two weeks, my roommate has been making kombucha at home. As I’ve observed the process and sampled the batches at each stage, I’ve gathered some notes about this particular art form. First Fermentation

Step 1: Brew black tea and add to SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast)

The car door opens to the back side of Andrews. Bowen Street is bustling with swarms of first years and their families—some, like you, who have only just arrived, and others who are preparing for tearful goodbyes. A swirl of mist drifts across your skin. In the rainy haze, you find blurry faces and buildings as you try to latch on to any signs of familiarity from your visit six months ago. For a moment, your shoes are glued to the ground as strangers and walls and time pass you in waves of vertigo. When your parents have their backs turned, you have the sudden urge to run to the car and drive back home. Your eyes begin to sting, but you blink away the tears and swallow the lump in your throat. You can’t start crying just yet.

Finally, you find the will to trudge up the glass stairs of Miller where your new home awaits, nestled in the corner of the second floor. The door knob turns, and one of your roommates greets you. You exchange hugs and introduce yourself to her parents. She seems to be settled in already, and that intimidates you. But in a way, it calms you too. You think maybe you’ll adjust with just as much ease.

The next few weeks and months are inundated with “nice to meet you”, “let’s get lunch”, “ratty at 6.” One day as you’re heading to class, you bump into someone who is also on his way out of Miller. You realize that you’re both heading to Salomon DECI for Principles of Econ. You follow him towards the front of the lecture hall (you wouldn’t dare to go so far forward on your own), and he leads you to a row where two girls are already seated in the middle. He breaks their chatter, and their gaze shifts onto you. You grin (or grimace) timidly to say hello. Fifty minutes later, class ends, and you grin (or grimace) again to say goodbye, then sprint out the door. Little do you know that this will become routine: walk together from Miller, sit in class, rush out to beat the flock. After a few more classes, instead of sprinting away at the chime of the bell, you join them for Starbucks or lunch at the Lotus Pepper food truck.

More activities become regular. Falling asleep on the Salomon balcony in CS15 until the Just Dance music jolts you awake for a stretch break, following your friends to the Jameson-Mead fourth floor lounge afterward and accepting the fate of the Keeney cough, taking the campus shuttle back to North Campus at the end of a long day.

Tea is the foundation for the kombucha’s flavor. Add in SCOBY and like a kombucha starter it begins to take effect.

Step 2: Add sugar and water

On your hunt for new study spaces, you excavate the treasures of the CIT fifth floor and the common room in Rhode Island Hall. Early signs of spring prompt you to brave your first adventure together outside the confines of campus. You set afoot to Wayland Square, admiring the houses on

Waterman and reintegrating yourself back into civilization.

The next year, you venture further down South Campus to Orwig then Coffee Exchange and Amy’s and Tea in Sahara. The housing lottery in April last spring left your group with the last two rooms in Perkins, but conveniently, this forces you to occupy new spaces and make them your own.

After testing with room temperature, storing locations, and ratios of water and sugar, eventually the correct conditions allow the SCOBY to consume the sugar and turn it into acetic acid, resulting in a fizzy carbonation. Here, the signature characteristics of kombucha start to emerge.

Step 3: Cover with breathable cloth, secure with rubber bands, and let sit for 7-10 days

Most days, however, are filled with nothing. Sprawled on the rug playing bananagrams, drinking Trader Joe’s Winter Wake Up Tea, sitting on the floor recounting events from the day in painstaking detail, telling the same stories over and over again. Laughing about uxnforgivable jokes, jokes that turn into comedic gestures, gestures that turn into a secret lingo until eventually you adopt mannerisms and adages from one another.

You attempt to pull an all-nighter on the last day. It’s already midnight and you plan on watching the sunrise, so you convince yourselves that “five more hours is nothing.” You crowd around a small laptop screen to watch She’s the Man, but a few moments later, exhaustion prevails. One friend slips next door to sleep in her own bed and tells you to wake her up in an hour. The rest of you curl up on the floor and hope that someone else has set an alarm. It was a valiant effort.

The alarm goes off, and everyone awakes groggily in disarray. The car ride there is silent as everyone snags a few extra minutes of rest. It’s already May, but the temperature outside feels like February. You blanket each other with warm embraces, and for a moment, the nothingness feels like everything.

Soon, you leave for summer break and before long, it’s already halfway over.

Oxygen seeps through the cloth. Hints of tartness and tanginess diffuse throughout the mixture, a quiet dance towards homeostasis.

Second Fermentation

Step 1: Pour previous fermentation from jar into smaller glass bottles

You return in the fall to a newly built dorm, completed so recently that the paint on the walls are still drying. At last, you have a room to yourself this year. The privacy is nice, but the ceilings stretch unusually high, the air is a bit colder, and the silence is slightly unnerving.

Eventually, you realize that peacefulness is an indication of stability. You burrow in the nooks of your new comfort spots. You make Nitro Bar a routine, and Lincoln Woods becomes your refuge. The pictures in your camera roll are adorned with the cozy, muted palette of autumn and the usual rotation of familiar faces you see every day. Your bubble crystallizes, almost to the point of imperviousness. In your world, only ten to fifteen people exist, but for now, you’re okay with that.

Smaller seal-tight jars allow for further carbonation. In a more controlled environment with less exposure to air, the bubbles develop more intensely as the kombucha ferments for longer.

Step 2: Add fruit and sugar to taste

After a short while, the monotony pleads for a change, another period of experimentation and

exploration. This time, you have more mobility, more freedom to roam. You escape to the coast of Massachusetts and Maine and the mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire, until you’ve scattered memories along every path in New England.

New flavor dimensions from fruit and spices are combined to personalize the kombucha to your own taste. After much trial and error, the perfect concoction does exist.

You buy tickets for three concerts, a year in advance for next fall. You become interested in post- after your friend tells you she needs another writer in her section. When another friend says he needs more drivers for his club’s ski trip, you say yes despite only knowing two others who are going. The solar eclipse is two weeks away, and you plan a last minute trip to Burlington, Vermont to be in the path of totality. On the drive up, the anticipation is palpable.

The sun comes out more often now. It’s National Ice Cream Day, and you get your free cone from Ben and Jerry’s. The sweet taste of mango lingers, and you savor it until the very last bite. On your walk back to the Main Green, you stop by a tawny brown house that’s soon to be yours. You’ve walked past it probably hundreds of times before, but this time it’s just the three of you so you pause to take a picture together.

You take another picture like this on the first day of senior year.

Step 3: Screw tight and let sit for 2-3 days

This half of the year has felt shorter than the first, and the days seem to slip away ever so quietly. So you slow it down a bit. You sit on a dock and bask in the sun. He’s reading John Green, and you’re reading Hiroko Oyamada. On the car ride to and from Maren Morris, you listen to her talk about study abroad and share stories that span the past and the future. Each moment you’ve spent in a coffee shop together, your stay grows longer — an hour and a half at Coffee Exchange, two and a half at Nitro Bar, nearly five at Little City and Caffe Nero. You trust in the timing of things.

With patience and persistence, the final product is one crafted with love, devotion, and understanding.

It’s 9:00pm. You have two assignments to finish before class tomorrow, but your friend has a flight to catch at 6:00am, so you plan to stop by her house for a few minutes to give her cookies that you and your roommates baked last night. She hands you a Fun Dip in exchange, then you drive together to meet with another friend. She hops into the car too, and now you’re in your typical formation: huddled around the center console, heads nearly touching, entranced in laughter and conversation.

You don’t remember what you talked about or how an hour has passed — an hour that turns into two weeks, three months, four years.

Graduation is 95 days away. You can’t start crying just yet.

by Gabi Yuan

Illustrated by Chase Wu

I open one eye and peer down towards her hands. Her black, shaggy hair has grown longer, the uneven ends resting across the front of her shoulders. The patina white yarn is stretched across her lap. While her face is not in view, I know her mouth rests closed, lips pressed gently together. Her eyes are watching the screen in front of her, her hands moving quickly to the pace of the show—twisting in and out, in and out, through that gentle, oatmeal color.

Feeling my gaze, she looks to me, placingthe knitting needles down.

I smile back, signaling towards her hands.

“What’re you making?”

As I trace the back of her almond-colored sweater, the texture once yarn, she tells me a story.

The lamp to her right side hums lightly. At nighttime, her hands are cold against her bare legs. While outside the ground is barren of snow, she learns to knit for an Alabama winter. Her hands move to her ears, to the tip of her nose, her cold fingers leaving an icy lull.

While she initially learns to knit to make a balaclava, a utility to stay warm, she realizes the activity’s purposeful distraction, the mindless concentration, and it draws her to continue.

I’ve always admired a crafter, someone able to sit down, to continue with intention and purpose. To learn a skill like this from scratch is a talent I have never obtained.

So, as I watch the repetitive process now—she picks up both needles once again, weaving a continuous intersection of loops— fascination consumes me. The needle contains and continues the stitch. She weaves without hesitation. Soon, the patch grows longer, the

once singular thread now formed to a textile. She picks up a different ball of yarn, weaving the moss green into the bottom of the off-white yarn. I watch as her hands slow to become accustomed to the addition, then picking back up until another section emerges.

The green situated to the textile, rhythm steadying, her expressions slackening. Yet, my heartbeat quickens, watching her hands move rapidly. There’s a balance: the faster her hands move, the softer her features grow—eyes lowered, half-closed. She looks almost asleep, the way her mouth hangs loosely open. The sound of the metal knitting needles coinciding with each other puts me at ease.

Observing a crafter in their element is an art of its own.

Later, when we’re lying beside one another, my face tucked into the opening between her chest and shoulder, she tells me how it feels.

I picture an end goal, she begins.

Walking into the yarn store, choosing among the different fabrics displayed, is an art. I watch her pace around the small, enclosed store. With yarn pooling from every edge of the wall, I wonder how she’ll ever make up her mind. Yet, as she holds each skein of yarn in front of her, she’s comparing the color to the image formed in her head. She switches the murky shade of white for a lighter beige, then exchanges the forest for an olive green.

After minutes of deliberation, moving on to the other side of the wall, she curates a final selection. Walking out of the store, my curiosity is brimming.

“What’re you making?” I ask.

As I begin to work, she continues. She rummages through different patterns, drawing from images she's remembered or

saved before, deciding on familiar patterns or something new.

Yet, I only recognize complexity through the craft’s texture. Before I even look, I feel for the intricate markings. She gently takes the patch away.

If you play with it any longer, you’ll figure it out, she says.

I reach for some loose yarn to hold instead. Using my two index fingers as knitting needles, gluing them together as flexible wire, I pretend I am working hard, to craft something she can enjoy.

Sitting in the library, or resting on her bed, or temporarily sitting on a bench outside, in her hands is always her yarn, her needles.

It’s been days and I still haven’t figured out what she’s making. I peek into her bag, looking for designs or scraps or any trace of a plannedout project. With no clues, not even the colors guiding me to a guess, I slump back.

She nudges me with the edge of her shoulder. Come, she says.

Taking my hands in hers, she places a needle in each and slowly mimics weaving. While my eyes follow the rhythmic movements, they’re too sudden to understand. I watch as one needle goes under while the other needle goes over, twice. Then, before tightening to loop the entire stitch together, she moves the left needle again, then the right. Before long, a single stitch is formed.

Close your eyes, she whispers in my ear. Through the yarn, the stitching, the misplaced textiles, I’m searching for an art of my own to begin.

Perhaps it’s also been here, weaving the mismatched sentences and spaces between words.

by Rchin Bari

Illustrated by Fiona McGill

The universal mind is a metaphysical concept that claims all beings in the universe share a common consciousness. Though only speculation, it is an idea that is as fascinating as any other postulation about how our infinitely large and mysterious world truly operates. That implies everything from water to humanoid creations holds some degree of consciousness. This idea has always intrigued me, especially during winter. As I watch the snow fall and gather into piles, I can't help but wonder: if snowmen could think, what would they say? What would they feel?

One winter, my friends and I built a snowman, and though he never spoke, I imagined his fleeting existence…

On a cold, windy day atop the hill I call home, I am brought to life by alien-looking beings, who form me from the ground up with their tiny gloved appendages. They call me Frost McBumfulsmith, a name that emerged from a flurry of suggestions. One suggested “Sir Frostington,” another championed “Captain Snowface,” but in the end, “Frost McBumfulsmith” won. I am made out of three balls of snow, a variety of rocks, a scarf around my neck, a hat on my head, and a carrot for my nose. My creators’ laughter rings through the air; though I can’t speak nor move, in their eyes, my existence is enough.

From my spot atop the hill, I see another snow creature like myself. They, too, brought joy to these fleshy beings. Their creators' smiles gleam, for their joy is our own, giving our frozen existences meaning, for we exist only because of them.

But all my joy is fleeting as I watch silently and helplessly, in snowbound terror, as they hurtle down the hill on their sleds, smashing through my kind without a second thought. Unable to move, all I can do is bear witness.

I think I must be next. Somehow, I am spared.

As time passes, the sun leaves the sky. I remain standing.

Yellow buses pick up and drop off my creators, who

point at me and smile, proud of their creation. This happiness melts away faster than the snowflakes that built me. At first, my creators’ eyes light up at the sight of me, their joy radiant. But soon, their gazes grow shorter, their smiles thinner, until I become just a pile of structured snow that once brought them happiness. It hurts at first, but one gets used to the apathy.

The days grow warmer. Birds flutter around me, oblivious to my silent suffering. The glowing laser in the sky, that tyrant of heat and light, mercilessly burns me. My once-proud form shrinks under its relentless gaze, each droplet of water a testament to my slow decay. I constantly pray for the cold rock in the night sky to grant me refuge from the unbearable burns, even if it is only for a few hours.

Sometimes, the pain of burning becomes unbearable, and I scream, but no one can hear me. Besides, what does it matter if a lousy snowman like me is saved? My rocks, once forming my mouth, have fallen off, along with the sticks that were my arms. My head detaches, and I can see the mound that was once my body.

My creators, why won’t you look at me? Why have you abandoned me? Why must I suffer alone? Why me?

Birds come to peck, eating the carrot that was once my nose. The rocks from my middle and lower sections tumble away, yet my eyes remain intact. I tilt until my entire world turns upside down. I am ready to accept my inevitable fate.

Then, a bird pecks out one of my eyes. The darkness engulfs me.

As I melt away, a deep sorrow fills my soul. I lived to stand and stood to fall. This is truly the end. My sight, my vision, my emotions: all eternally gone.

As I lay upon what remains of my head, slowly fading, I know this is it. The sun’s return fills me with fear, yet the burning sensation ceases. The pain that once haunted me fades to peace; all is now dark. I have lived. I fulfilled my task. Now I perish.

Ishan Khurana

(something that's sent in the mail)

“Neither boyhood nor girlhood have rung true for me, nor do I think they ever will. I”m stuck, precariously toeing the line between the two, splitting my personality in messy halves and assigning each piece to a side.”

— Audrey Wijono, “Boyhood and Me” 03.10.23

“Fall is the most delicate season. The way the leaves crinkle, changing color so romantically, falling for us to step through like clouds, short-lived and fleeting. The breeze tickling us each time we walk outside without a jacket serves as a reminder of what is to come.”

— Gabi Yuan, “The Delightful Ever Changing of Seasons” 02.29.24

or the name of a Star Wars movie (_____ One)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Emilie Guan

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Klara Davidson-Schmich

Section Editors

Daphne Cao

Elaina Bayard

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

Elijah Puente

Section Editors

Lizzy Bazldjoo

AJ Wu

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Katheryne Gonzalez

Section Editors Gabi Yuan

Chelsea Long

LIFESTYLE

Managing Editor

Tabitha Lynn

Section Editors

Daniella Coyle

Hallel Abrams

Gerber

POST-POURRI

Managing Editor

Susanne Kowalska

Section Editor Olivia Stacey

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Junyue Ma

Kaitlyn Stanton

COPY CHIEF

Jessica Lee

Copy Editors

Indigo Mudhbary

Anika Kotapally

Lindsey Nguyen

SOCIAL MEDIA

Managing Editor

Tabitha Grandolfo

Section Editors

Eliot Geer

Chloe Ovbiagele

LAYOUT CHIEF

Gray Martens

Layout Designers

Amber Zhao

Alexa Gay

James Farrington

Irene Park

STAFF WRITERS

Nina Lidar

Gabi Yuan

Lynn Nguyen

Ben Herdeg

Daphne Cao

Indigo Mudbhary

Ishan Khurana

Sofie Zeruto

Sydney Pearson

Ayoola Fadahunsi

Samira Lakhiani

Ellyse Givens

CROSSWORD

AJ Wu

Ishan Khurana

Lily Coffman