Welcome to a trilogy that exposes the hidden history of disease as a weapon — from colonial cruelty to Cold War secrecy, from the betrayal of Black communities to the ethical crossroads of modern science. This eBook is more than a timeline. It’s a legacy-powered archive. A call to remember, resist, and reframe.

Whether you’re a researcher, activist, artist, or truth-seeker, this series invites you to explore how power has shaped biology — and how storytelling can reclaim it.

Part 1: Colonial Germ Warfare

The story of the smallpox blankets — a chilling tactic used against Native Americans during Pontiac’s War.

Part 2: Cold War Labs to CRISPR

How bioweapons evolved from anthrax stockpiles to synthetic biology and gene editing.

Part 3: Safeguarding the Future

Tuskegee, ethics, and oversight — reclaiming science for healing, not harm.

This eBook is part of PHILLYGHOSTWRITER’s mission to honor Black and Indigenous legacies through creative storytelling, historical research, and digital publishing.

From Blankets To Genomes — The Untold Story Of Germ Warfare.

Frank Porter

Your Friendly Neighborhood Ghostwriter Founder of PHILLYGHOSTWRITER

| Since 1980

1763 – Fort Pitt: British officers give smallpox-infected blankets to Native Americans during the Pontiac War’s Peace Negotiations.

“From Smallpox Blankets To Synthetic Biology — America’s Untold Story Of Germ Warfare.”

When we talk about colonization, we often focus on land seizures, forced conversions, and military campaigns. But one of the most chilling tactics used against Indigenous peoples was the deliberate spread of disease. The infamous “smallpox blankets” of 1763 remain one of the earliest documented attempts at biological warfare in North America.

• In the summer of 1763, Native warriors from the Delaware, Shawnee, and Mingo nations laid siege to Fort Pitt (present-day Pittsburgh) during Pontiac’s War.

• Inside the fort, British soldiers were already battling an outbreak of smallpox among their own patients.

• Captain Simeon Ecuyer, the fort’s commander, feared both the siege and the disease spreading further among his troops.

“We gave them two blankets and a handkerchief out of the smallpox hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect.” William Trent’s journal, June 24, 1763

Ecuyer and Trent gave Native emissaries two blankets and a handkerchief taken directly from the fort’s smallpox hospital.

This was not a widespread program but a single, deliberate incident — enough to symbolize the ruthless mindset of colonizers.

• Brief handling: They did not sleep in or wear the items, only passed them along.

• Existing immunity: Many Europeans had already survived smallpox earlier in life, leaving them scarred but immune.

• Transmission limits: Smallpox spreads most effectively via respiratory droplets, not fabric. Blankets could carry the virus, but infection risk was lower compared to direct contact with a sick patient.

• Calculated gamble: Colonizers believed the disease would devastate Native communities more than themselves.

• Historians debate whether these blankets directly caused outbreaks among Native tribes. Smallpox was already circulating widely, so proving causation is difficult.

• Regardless, the attempt is considered one of the earliest documented cases of biological warfare in the Americas.

• The story endures because it represents the weaponization of suffering — a chilling reminder of how colonizers viewed Indigenous lives as expendable obstacles to conquest.

The “smallpox blankets” of Fort Pitt were not advanced technology but opportunistic cruelty. Yet they set a precedent: disease could be wielded as a weapon. This incident is more than a historical footnote — it is a warning. What colonizers once attempted with contaminated linens, modern powers could attempt with engineered pathogens.

If the “smallpox blankets” of Fort Pitt symbolized opportunistic cruelty, the Cold War marked the beginning of systematic bioweapons programs. Both superpowers experimented with pathogens, stockpiled agents, and tested delivery systems. Though treaties outlawed their use, clandestine research continued. Today, advances in synthetic biology and gene editing raise the stakes even higher.

1. United States: Began an official bioweapons program in 1943, weaponizing agents like anthrax, tularemia, brucellosis, Q-fever, botulinum toxin, and staphylococcal enterotoxin B.

2. Soviet Union: Ran one of the largest clandestine programs, continuing even after signing the Biological Weapons Convention (1972). Soviet labs engineered pathogens like plague and anthrax on an industrial scale: Britannica

3. Japan’s Unit 731 (WWII legacy): Conducted horrific human experiments, infecting prisoners with plague, cholera, and anthrax. This legacy influenced Cold War fears and U.S. decisions to pursue bioweapons research: Britannica

4. Treaty limits: The Geneva Protocol (1925) banned use, and the Biological Weapons Convention (1972) banned development and stockpiling. Yet enforcement was weak, allowing violations to persist: National Defense University Press.

Synthetic Biology and Gene Editing Risks

• Dual-use dilemma: Tools like CRISPR-Cas9 make genetic editing cheap, fast, and precise. What heals can also harm.

• Synthetic bioweapons: Unlike traditional pathogens, engineered organisms can be designed to evade vaccines, resist antibiotics, or target specific populations: U.S. Naval Institute.

• AI acceleration: Machine learning now helps design novel organisms, democratizing access to knowledge once limited to elite labs. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

• Weaponizable cures: Research into vaccines and therapies could be inverted — a cure for one population might be withheld or flipped into a weapon against another.

Georgetown Journal of International Affairs.

COVID-19 as a wake-up call: A naturally occurring virus disrupted economies and militaries worldwide. Imagine a deliberately engineered pathogen.

• Global governance gaps: Current treaties lack strong verification mechanisms. The Biological Weapons Convention is underfunded and poorly enforced. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

• Future threats: Synthetic biology could enable “designer diseases” — pathogens tailored for maximum disruption.

The Cold War showed how nations flirted with bioweapons despite treaties. Today, synthetic biology represents a new frontier of risk. What colonizers once attempted with contaminated blankets, modern powers could attempt with engineered genomes. The challenge is clear: humanity must strengthen global governance before innovation outpaces ethics.

From smallpox blankets to Cold War biolabs, the weaponization of disease has evolved — but the moral dilemma remains. Today, synthetic biology and gene editing offer miraculous cures, yet they also open the door to designer pathogens and targeted bioweapons. The question is no longer can we — it’s should we. And who gets to decide?

1. Biological Weapons Convention (BWC, 1972): Prohibits the development, production, and stockpiling of bioweapons.

2. Weak enforcement: The BWC lacks a verification regime — unlike nuclear treaties, it has no inspections or penalties.

3. Calls for reform: Scientists and ethicists urge stronger global governance, including transparency, whistleblower protections, and real-time monitoring of biotech labs.

4. Dual-use dilemma: Technologies like CRISPR and AI can be used for healing or harm. Oversight must evolve with innovation.

• Bioethics boards: Many countries have advisory panels, but few have binding authority.

• Open science vs. secrecy: Sharing research promotes cures, but secrecy breeds misuse.

• Community consent: Indigenous and marginalized communities must be consulted when biotech affects their health, land, or legacy.

• Education and transparency: Public understanding of biotech risks is essential to democratic oversight.

1. Legacy framing: Just as colonizers used disease to erase cultures, today’s storytellers can use narrative to protect them.

2. Creative resistance: Art, fiction, and public campaigns can expose hidden risks and demand accountability.

3. Empowerment through knowledge: Communities must be equipped to ask hard questions: Who funds this research? Who benefits? Who is at risk?

The future of biotechnology is not just a scientific challenge — it’s a moral one. From Fort Pitt to CRISPR, the arc of germ warfare shows how power can corrupt innovation. But it also shows how ethics, advocacy, and storytelling can reclaim that power.

We must build a world where cures are never weaponized, where oversight is real, and where communities — not corporations — shape the future of life itself.

In the early 1800s, Britain faced a problem. They were importing tea, silk, and porcelain from China, but China wanted nothing in return from the West. Silver was draining from British reserves, and the empire needed a product that could force open China’s markets. They found it: opium.

• Industrial-scale trafficking: Grown in British-controlled India, refined into smokable form, and smuggled into China despite its ban.

• Profit margins of 400–500%: A chest of opium bought cheaply in India could be sold for five times its value in China.

• American involvement: Families like the Delanos (ancestors of Franklin D. Roosevelt), the Astors, and the Forbes joined in, using fast clipper ships to outrun Chinese patrols and flood the country with drugs.

By the 1830s, an estimated 10–12 million Chinese people were addicted—nearly 10% of the adult male population.

Silver drained from China’s economy, families collapsed under the weight of addiction, and the nation was destabilized. When Commissioner Lin Zexu tried to stop the trade in 1839, Britain responded with war. China lost, was forced to sign unequal treaties, and ceded Hong Kong. The humiliation lasted a century.

Meanwhile, in America, the fortunes made from this devastation they built mansions, universities, and dynasties. Roosevelt’s Harvard education, Yale’s Skull and Bones society, and Forbes Magazine all trace their roots to opium profits.

The poison that destroyed China became the foundation of American Aristocracy and China’s “Century of Humiliation”.

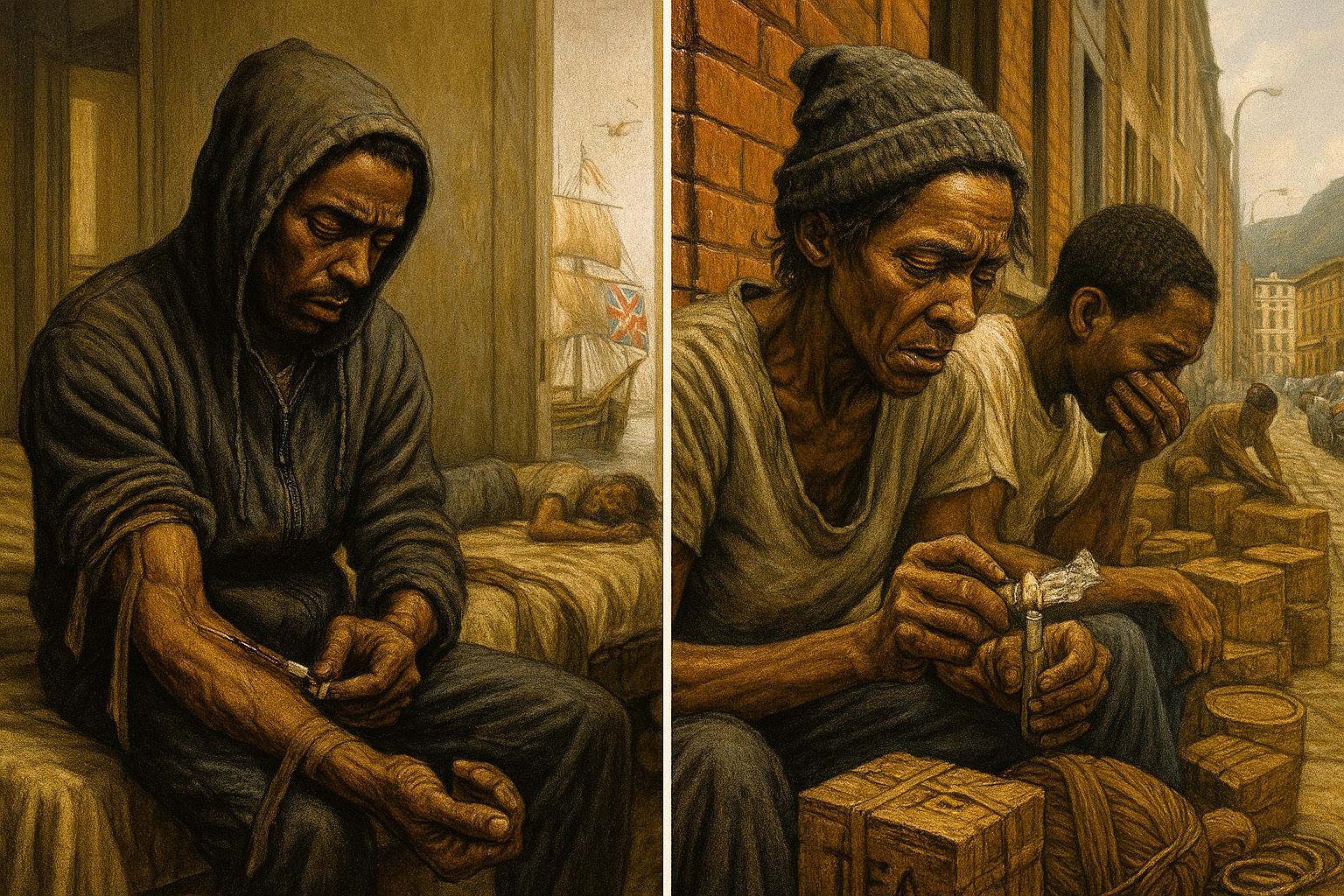

The Opium Wars weren’t just about China—they were about a global strategy: use addiction to control communities of color, then erase the evidence. The same blueprint was later applied to Black America with crack cocaine. The difference?

Instead of foreign colonization, it was domestic colonization—targeting African Americans in their own neighborhoods.

1940

1980

1. Smallpox blankets at Fort Pitt (1763)

2. Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972)

3. Cold War bioweapons labs and CRISPR risks

• Opium Epidemic in China (19th century): Britain’s deliberate flooding of China with opium during the Opium Wars weakened society, destabilized governance, and opened the door to colonial control.

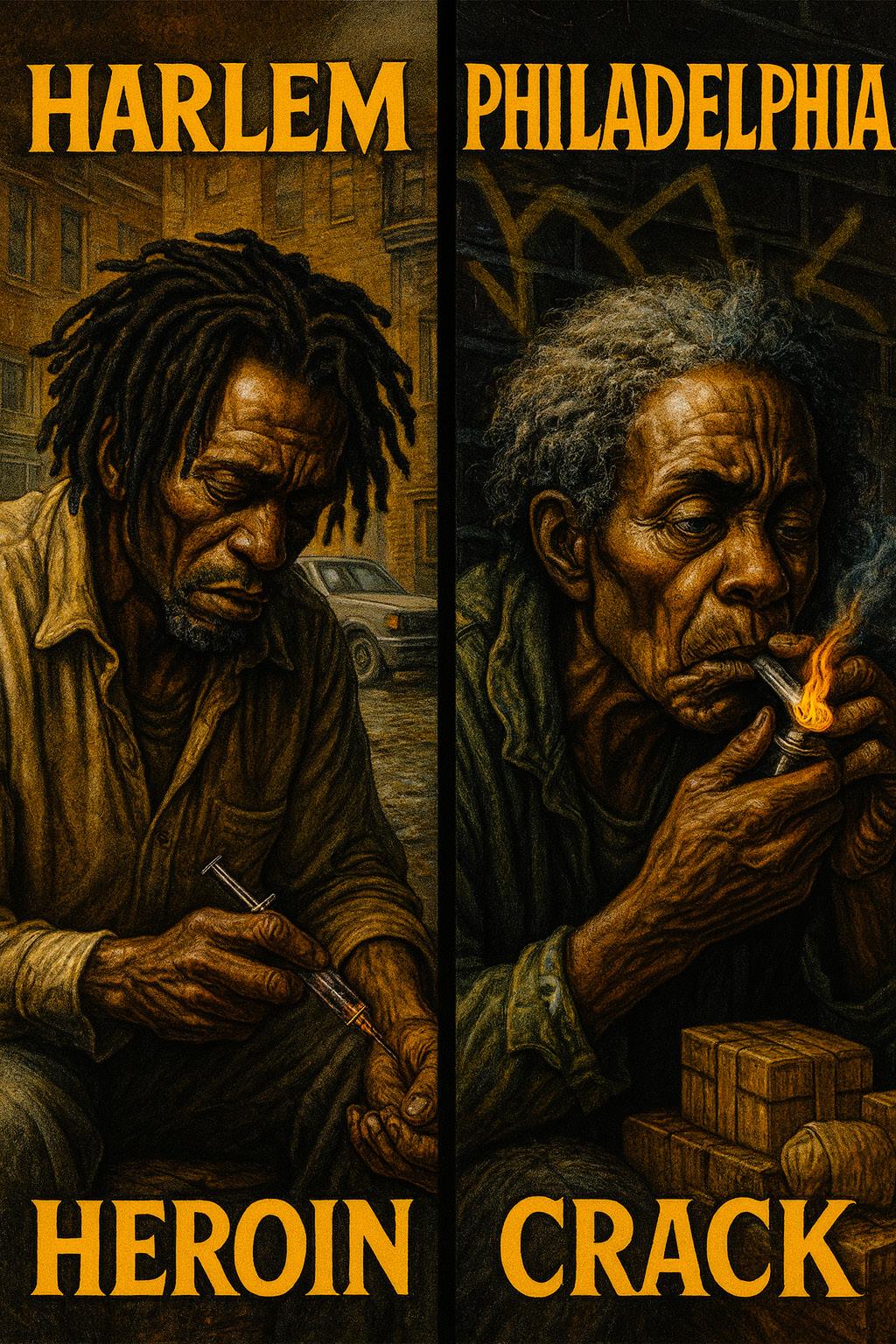

• Heroin Epidemic in Harlem (1960s–1970s): Targeted distribution of heroin devastated Black communities, eroding family structures and fueling mass incarceration.

• Crack Cocaine Epidemic (1980s–1990s): Crack’s spread in urban Black neighborhoods became a form of social warfare — destroying health, fueling violence, and justifying punitive policing.

1. Weaponized neglect: Just as Tuskegee withheld penicillin, narcotic epidemics withheld healing and instead delivered destruction.

2. Colonial logic: Whether through germs or drugs, the tactic was the same — destabilize communities to consolidate power.

3. Legacy of mistrust: These epidemics reinforced the perception that marginalized communities were expendable, echoing centuries of exploitation.

Closing Reflection: Truth, Legacy, and Dedication History is not just a record of the past—it is a mirror of the present. From opium dens to crack houses, addiction has been weaponized against communities of color. The names of the powerful are celebrated, their crimes erased, while the resilience of melanated people is silenced.

But silence is not our destiny. We are survivors, visionaries, and architects of justice. By telling the truth, we reclaim what was stolen. By demanding reparations, we plant seeds of healing. By refusing erasure, we ensure our children inherit dignity, not devastation.

This blog post is dedicated to Maleak Ali, founder of UNDERGROUND NATION INTERNATIONAL LLC, whose vision and courage initiated the UNI Petition. His leadership reminds us that justice is not given—it is demanded.

We are not victims of history—we are its authors. And today, we write a new chapter: one of truth, justice, and liberation.

germs → labs → CRISPR, then opium → heroin → crack.

“Whether through blankets or crack vials, the logic was the same: weaponize vulnerability.”