Lecture 2023–24

What London can teach the rest of the world

Colleen Harris MVO DL

What London can teach the rest of the world

Colleen Harris MVO DL

Communications

and

diversity professional with more than 30 years’ experience.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions presented do not necessarily represent those of the Trust. The Trust accepts no liability for the content, or consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided.

Copyright © Colleen Harris and The Portal Trust

First published in the UK in 2024 by The Portal Trust. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-7396318-4-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Designed by Andrew Barron/Thextension Printed in England by Gavin Martin Colournet Ltd.

The Portal Trust 31 Jewry Street, London EC3N 2EY

www.portaltrust.org

uk.linkedin.com/company/the-portal-trust

twitter.com/Portal_Trust

instagram.com/Portal_Trust

4

Foreword

Denise Jones

Deputy Chair and Chair of Grants

The Portal Trust

6

Chief Executive’s Foreword

Richard Foley, Chief Executive

The Portal Trust

8

What London can teach the rest of the world

Colleen Harris MVO DL

24

Colleen Harris Biographical note

Foreword

Denise Jones Deputy Chair and Chair of Grants

Welcome to the commemorative brochure for the Portal Trust’s Education Lecture of 2023–24.

The annual lecture is always a highlight in our calendar, offering a unique opportunity to come together, explore new ideas, and engage in thoughtful discussion on issues that matter to us all.

The following pages present the talk delivered by Colleen Harris, whose insights are personal and deeply relevant to the challenges of the modern world. I hope her words will leave you with much to reflect on and discuss, as they certainly have for me.

This past year has brought both challenges and opportunities, which we have met with resilience, innovation, and a renewed sense of purpose. We have supported projects that provide valuable, practical work experience for ex-prisoners, alongside others that offer leadership training for those aspiring to enter the creative industries. Throughout the London Boroughs your projects – our projects – have ignited sparks of potential in countless young minds.

We are also pleased to have extended our collaboration with Bayes Business School (where this lecture series is held) for another two years on their outstanding School’s Engagement Programme. As the programme approaches its ten-year milestone, we are eager to reflect on the progress made so far.

If reading text isn’t for you, please do watch Colleen’s lecture in full, on our website at https://portaltrust.org/ news/portal-trusteducation-lecture-2024 instead.

Want to join us at the next lecture? Email events@portaltrust.org or keep an eye out for announcements on our website or social media

At the Portal Trust, we have always believed that diversity is not just something to be supported – it is something to be celebrated. Our two schools provide students with an environment where differences are embraced, and every individual has the opportunity to thrive. We are delighted to see them continue to go from strength to strength, serving as beacons of outstanding education for young people in East London.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Colleen for her time and thoughtful contribution to this evening’s event, as well as the staff teams at The Portal Trust and Bayes Business School, who work hard to make this lecture series a success each year. Last but certainly not least, I would like to thank our guests on the night, and you, the reader, for your support and engagement.

Thank you once again, and I hope you enjoy reading Colleen’s talk, titled What London Can Teach the Rest of the World.

Foreword

Richard Foley Chief Executive

Richard Foley Chief Executive

The Portal Trust is an independent London-based education charity that supports young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to reach their full potential. With a focus on building skills, knowledge, and confidence, we believe every individual deserves the opportunity to flourish in an environment that values their unique strengths and perspective. For over two hundred and seventy-five years we have invested in educational initiatives across London that not only deliver immediate benefits but also lay the groundwork for long-term success.

As Chief Executive of The Portal Trust, it is my pleasure to introduce this year’s lecture brochure—a record of an event that reflects our commitment to supporting both our beneficiaries and the wider education sector.

This year’s lecture was delivered by our diversity consultant and colleague, Colleen Harris MVO DL. Her insights, drawn from a wealth of experience, offer a unique perspective on diversity and modern life. I am confident her words will inspire reflection and action among all who read them.

I extend my sincere gratitude to Colleen for her contribution and to the dedicated teams at the Portal Trust and Bayes Business School for their collaboration. And to you—our supporters and partners, I’d like to thank you for sharing this journey with us.

I hope you find Colleen’s lecture as enlightening and impactful as I have.

Lastly, I am pleased to announce that Dr Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museums has agreed to be our speaker for the next Portal Trust Education Lecture at Bayes Business School in the autumn of 2025.

For details of next year’s lecture, do keep an eye on our website at www.portaltrust.org, or follow us on on X, Instagram or LinkedIn

What London can teach the rest of the world

Let me start by thanking Bayes Business School and the Portal Trust for giving me this opportunity to speak to you today. I know that this is an unusual privilege. This podium is normally reserved for the educated and informed. I am a spin doctor and Diversity consultant by trade, so no one could accuse me of being either informed or educated!

Apart from the wonderful Baroness Floella Benjamin sadly being unable to speak to you today, I imagine that the reason for inviting me to stand in for her is because of the importance that Bayes and the Portal Trust place on the work of education and diversity.

If education is about anything, it’s about making sure that everyone, regardless of background, is given the chance to fulfil their potential and improve their life chances.

Once I mention diversity I’m usually met with raised eyebrows and looks of disinterest. The word diversity can evoke that feeling that you’ve heard it all before. It’s done. But for me – one of the ‘diverse’ I’m reminded of the plaintive question asked by Rodney King after the Los Angeles riots nearly 20 years ago. The question still resonates unanswered: Why Can’t We Just Get Along?

The amazing Portal Trust, like many charitable institutions provides educational opportunities for young people facing disadvantage. The Portal Trust, however, is unique because it operates mainly in London. An organisation dating back to 1748 – steeped in the history of London – is looking to the future of the city and investing in its young people.

Both Bayes Business School and the Portal Trust sit centre stage in London’s history and its future. Both have in recent years become synonymous with excellence in education for all as well as a respect for diversity.

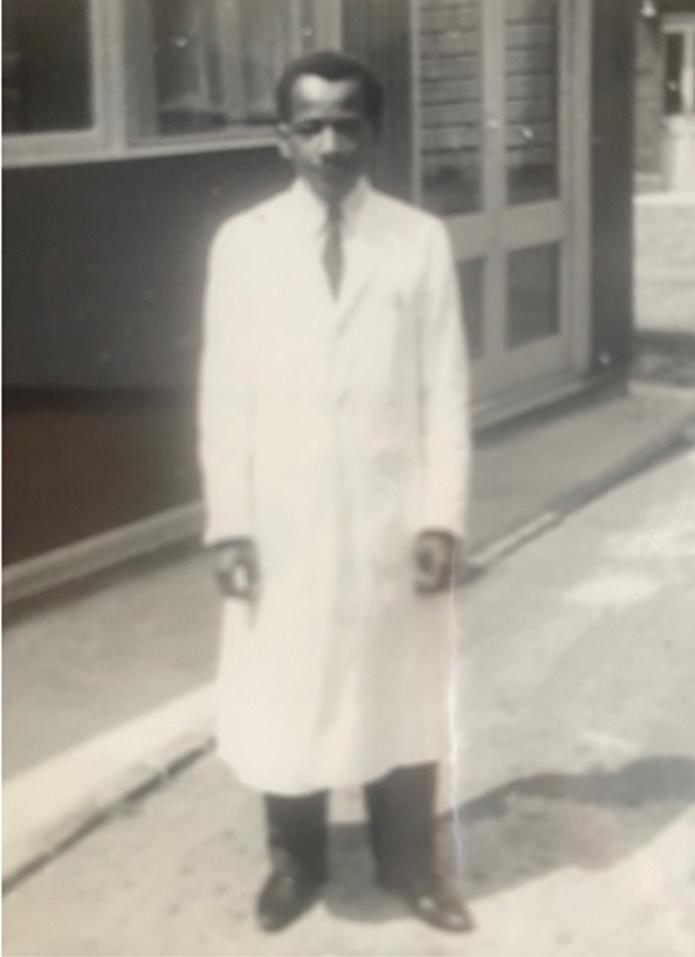

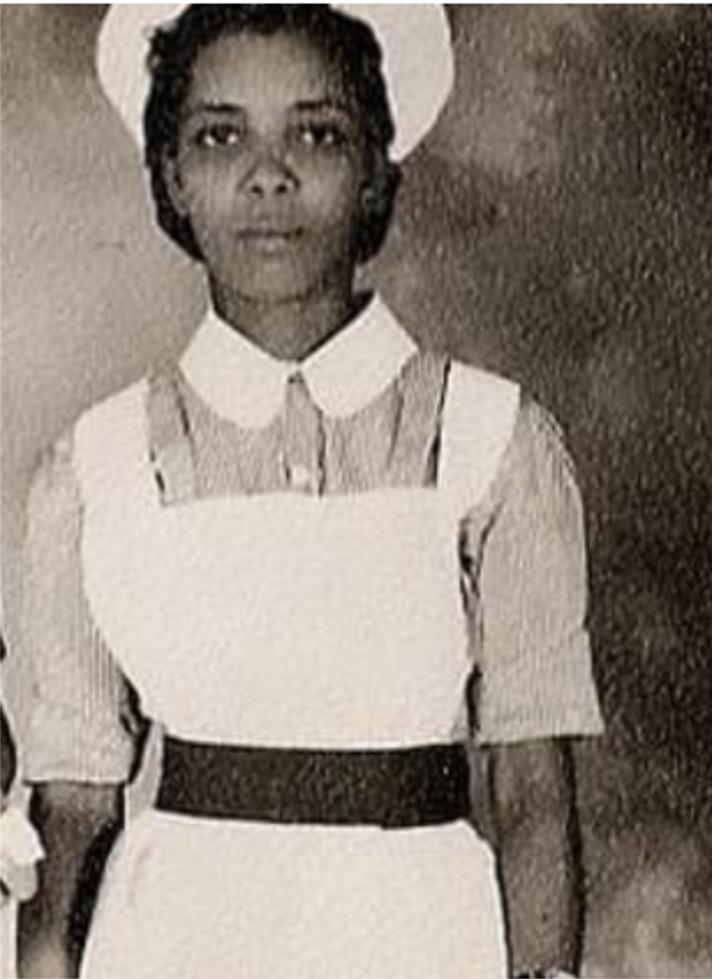

Colleen’s Mother and Father

They both stand as testament to the power of knowledge, while also serving as positive examples of how acknowledging racial issues and embracing diversity can benefit the fabric of our society and pave the way for us to all just get along.

Today’s lecture

Today I am going to talk to you about London’s historic reputation as the brainy city that opens its arms to the world, welcoming people from diverse backgrounds and cultures. This diversity is not just tolerated, it is celebrated.

To say that we celebrate diversity used to offend me, but I have now chosen to see it not merely as a superficial gesture, but a commitment to creating environments where everyone feels respected and valued. Where people feel empowered to contribute their unique perspectives and talents making London a city where anyone can find their place and contribute to its ongoing story.

But first, who am I?

London born and bred. Child of Gladstone & Sheila, a pharmacist, and a nurse, who travelled from Guyana to join the NHS in their hour of need.

Part of the Windrush generation that helped to rebuild Britain and that is now both loved and sadly, sometimes a little misunderstood.

Teaching, my chosen career, was not for me and after a spell in the British Museum and the Natural History Museum where I was the lone Black staff member in any of the offices, I experienced both horrendous and some funny racial banter or taunting (depending on your perspective). Great stories for my book!

I ended up in government communications and was the first Black press officer in government across the whole of the UK. Then I went on to become the first Black senior press officer working for the PM in No.10. The first Black member of the Royal Household – yes me, not Meghan! Fabulous and fascinating experiences working at the heart of the British establishment. But the importance of belonging cannot be overstated and after years being ‘the only one in the room’ I was exhausted dealing with the banter and wanted some company.

Deputy Lieutenant for Greater London presiding over citizenship ceremonies

Eventually I sought solace in the diversity world – the Commission for Racial Equality and the Equality, and Human Rights Commission, the United Nations, and the WHO. All very diverse institutions.

And now, decades after my parents made the brave decision to leave their home country behind and move to England, I find myself as a Representative Deputy Lieutenant for Greater London presiding over citizenship ceremonies, where I represent the establishment and welcome new citizens to the UK. What a turn of events for the child of immigrants. Bravo Gladstone and Sheila!

We are living in an age of globalisation, the movement of people across the planet is increasing at a phenomenal rate. Bill Clinton said that globalisation is not a policy – it’s a fact – the only issue is how we respond to it. It’s not going to stop.

With that in mind it’s interesting to note that the United Nations estimates that more than 300 million people live and work outside their country of birth – and the city of London is home to some 4 million of these people.

London has become one of the most ethnically diverse and multicultural cities in the world.

Around 37 per cent of its population were born outside the UK, and over 300 languages are spoken. Motivations for leaving your home country can vary, like my parents seeking to further their careers and support the ‘Mother Country’, but London’s reputation as a global educational powerhouse is well-deserved and attracts many from far and wide. The city is home to some of the world’s most prestigious universities and educational institutions including Bayes Business School and City University.

And London’s commitment to education extends beyond its universities.

Our city boasts a diverse array of schools, colleges, and vocational training institutions, providing opportunities for individuals of all ages and backgrounds to pursue lifelong learning and skill development. Indeed, the Portal Trust supports two Trust Schools, Aldgate, and Stepney All Saints.

But London’s educational institutions are not just academic silos; they are active participants in the city’s economy. Research from these institutions drives innovation and entrepreneurship, contributing to London’s status as a global hub for technology, finance, and creative industries.

We see this with the links between the Portal Trust and the University of the Arts and the V&A for example.

With its deep historical roots, London has always been home to a mix of cultures, ideas, and innovations. It is a city where the echoes of the past meet the dynamic pulse of the future.

From the Roman establishment of Londinium to the bustling metropolis it is today, London has been a stage for historical events, scientific discoveries, and artistic movements. But what makes London truly remarkable is its ability to evolve and adapt, ensuring it remains at the forefront of advancements.

For example, in the realm of artificial intelligence, London has positioned itself as a global leader with the PM hosting the world’s first conference on AI.

But what truly sets London apart is its unique spirit – a blend of openness, diversity, and resilience. The latter has been demonstrated time and again throughout its history.

But in recent years London has been challenged in a different way – to move away from the trappings of its colonial history and become a city that not only accepts different people and cultures but finds a way for all voices to be heard and respected.

Empire Windrush brought one of the first large groups of post-war West-Indian immigrants to the United Kingdom, carrying 1027 passengers and two stowaways on a voyage from Jamaica to London in 1948. ©Alamy pictures

Just over 60 years ago the House of Commons debated immigration policy, when the Macmillan Government proposed controls designed explicitly to keep New Commonwealth migrants – Black people – out of Britain.

We know from the Cabinet papers that have since been released that this decision was motivated by a fear of increased racism, as well as the fear that allowing more Black people into Britain would create a backlash that threatened peaceful community relations. Many politicians did not agree with this view and just as Atlee had waved away complaints about the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948, they argued that we need not fear immigration; and that anyway it would ebb and flow with the economic needs of the country.

Similarly to the decline of the British Empire, globalisation has had many social consequences, and the response of British society is just as critical to our future prosperity now, as it was then.

Whatever your view it’s hard to ignore the fact that our long-term future is inextricably linked to the rest of the world by the bonds of international trade, by faster telecommunications and travel, and also by the threat of environmental and security challenges.

This is true the world over. But like other European nations we have a special set of challenges from globalisation, which are not shared with newer nations such as Australia and the United States. Our unique challenge lies in our imperial history. Globalisation means that we are increasingly colliding with our own past as those we previously colonised turn up here in the UK. This means that our approach to our multi-ethnic future cannot be the same as those newer nations.

The famous Caribbean folk poet Louise Bennett predicted as much in the 1950s when she wrote her satire Colonization in reverse which starts:

What a joyful news Miss Mattie Ah feel like me heart gwine burs –Jamaica people colonizin

Englan in reverse

By de hundred, by de tousan from country an from town

By de shipload, by de plane load

Jamaica is Englan bound

And she then put the key question in her own very special way:

What a devilment a Englan!

Dem face war an brave de worse; But ah wonderin how dem gwine stan Colonizin in reverse

We are as I say colliding with our past – but this time we are not the masters. We are, like all others in the West, having to negotiate our way through the management of migration essential to our economic prosperity. It isn’t a simple process.

Most of the increase in immigration is led by students. Indeed, England is one of the most successful nations when it comes to attracting overseas students, with around 484,000 student visas issued in 2022. The majority like to stay to get work experience here before they return to their own country.

Globalisation brings benefits for us, but at the same time, it changes what we mean by “us”, as many of those staying are not only from Commonwealth countries, but from places like China, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

The colour and culture of societies has changed: cultural homogeneity is a thing of the past. Globalisation has made the politics of identity the true politics of our time. And in recent years it has been dramatized by the debate over immigration.

What is more at issue at the moment is the degree to which communities can cope with the change.

We used to talk about ten or so ethnic minority communities, we can now identify in London alone over 40 substantial groups of people with recent foreign antecedents. We continue to have more different kinds of people – in the 2021 census there were 19 ethnic categories, a jump from nine in 1991, but given that a single category includes sons of Somali goat herders and Ghanaian lawyers it still seems to give quite crude picture.

There is also the challenge of greater transnationalism. This is a complex issue but in short, when migrants arrived a hundred years ago, they more or less broke with their past – it was too far and too difficult to consider going back.

Today, international travel and communications mean that you need not abandon the physical link with the past. People travel back and forth and beyond with ease.

The challenge of integrating new and settled communities as they live together both in the short and long term will continue to grow with ever-increasing globalisation. The global movement of people has not just increased but changed.

We acknowledge that a city of over eight million people will bring challenges and London, to date, has been good at working through the many kinds of difference which can sometimes lead to people feeling ostracised or disadvantaged.

However, for some in our society life is still all too often - ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.’ Minorities around the country find themselves disproportionately amongst those whose life chances are the least promising, who are more prone to be victims of crime, and who have higher rates of infant mortality and lower life expectancy.

As a diversity consultant of more than 30 years standing, many of the challenges remain. I am still asked for example:

How to prevent homophobic bullying at school and even in the workplace;

How to tackle gang culture – largely regarded as a Black issue;

How to ensure dignity and respect for people in care and carers;

Whether an employer can refuse to employ a hairdresser who wears the veil;

What constitutes discrimination against women, pregnant or otherwise;

We do know that, for example, whatever class you belong to, your race is an obstacle all by itself.

For example, African-Caribbean men and Pakistani men, when compared with white men of similar qualifications, will, on average, be earning between £5,000 and £6,500 less each year.

Today I can tell you with statistical certainty that an AfricanCaribbean boy has twice as much chance of seeing the inside of a jail as he has of taking a university degree.

I can tell you that a Gypsy or Traveller child has about a one in four chance of passing five good GCSEs, and virtually none of getting three A-levels.

And I can tell you that nearly 50 per cent of adults with a learning disability or difficulty in Britain have no qualifications.

More of us are defining ourselves as disabled. There are around 16 million disabled adults and approximately 750,000 disabled children in the UK. This suggests that disability affects at least one in five of us.

In the classroom, it’s no longer just about how we make sure we are meeting the needs of Black and Brown children. Today, the question is how we deal with a class with completely different pupils in June than it had in September – both how we meet the needs of the children who move in and out, with backgrounds and experiences which are utterly different from their classmates, and how we meet the needs of children who stay in one class while others arrive and depart.

Nor is it a question of whether disabled children are better off in special schools or in mainstream education.

Today’s question is how we deal in the classroom, in every school, with a wide range of special educational needs, including learning disabilities and difficulties and those with mental health challenges.

How do we deal with these trends?

All of us here today share common goals and aspirations. We work to make difference within our society a source of energy, potential and prosperity, rather than a cause of friction, segregation and inequality.

We work to improve people’s life chances.

We want to think about diversity – difference in a way which is about inclusion not division in a way which reflects the age of difference we now live in.

The task for our institutions, like the Portal Trust and Bayes is to keep us on course for greater equality even as the demographic terrain around us continues to shift.

The reality is that there are several barriers currently impeding successful integration. Some of them are straightforwardly about discrimination. Some of them are about class. Still others are systemic.

My vision is for an integrated society. It’s a vision which I’ve formed from my own personal experience, and as such I know that it might not resonate with everyone. That being said, my idea is that everyone signs up to a single core set of values held in common and defined legally – democracy, equality between people, the integrity of the person and freedom of expression; and when and where these core values conflict with ancestral cultural values, these core values must take precedence.

I know dramatic events of recent years are posing a profound challenge for all of us.

Where should the balance lie between two extremes?

On the one hand, old style cultural assimilation in which everyone is expected to discard their own heritage – ethnic, regional, linguistic – in favour of a single norm.

On the other hand, a cringing abandonment of the core values and behaviours that distinguish democratic, liberal, modern, Britain from other less diverse and open societies.

This delicate balance changes all the time. In this country matters are complicated, because on these large questions of culture and behaviour we tend to avoid explicit statements of what is and isn’t acceptable.

There’s a really bad reason for this. In the old days there was no problem in establishing where the balance stood because in those more deferential, less democratic times, the middle classes, the London Times, the BBC, and the man from the Ministry just told us what to think and how to behave.

There’s a new urgency to this question of integration especially in a big city like London.

When people like my parents first came here there was a readymade engine of integration – the workplace. People worked in big factories (Ford car plant), big transport organisations (London Underground) or big public services (the NHS and the Post Office). They learned British ways at the elbows of their workmates who became their friends.

Where they came from, they played with a bat and ball and a game lasted four or five days. Here football mattered more than cricket and you had to have a team on a Saturday.

Where they came from part of the day’s fun was getting two extra mangoes for five cents less in the local market. They learned that you don’t bargain with shopkeepers.

Where they came from you could dance with anybody any time. Here you needed to sink five pints to get up the courage to go on the dance floor.

Today it’s not so easy to find an engine for integration. The size of the average workplace has shrunk. After COVID many of us are spending more time working from home. And when we are in the office or store or the factory, we’re staring at a screen or a phone.

There’s a job to do in making sure newcomers are welcomed and get the chance to see in practice what it’s like to be British.

It is education – especially schools and universities – where we meet people who don’t have the same background as we do. That makes what the Portal Trust and other educational institutions do not just a good way to help people pass exams – it makes it part of the glue that holds our society together.

Without real interaction there can be no real integration.

We are all trying to find the answers to the implied questions –how can people of very different and not-so different traditions, cultures and needs find a way of sharing the same space?

Has our historic policy of multiculturalism led to a more integrated society or to more polarised communities?

Do we need a more explicit assertion of our common national identity, our Britishness; and if we do, how should we express and promote that identity?

Resolving this balance must be a task for the whole nation. We need a mechanism to negotiate and renegotiate the social rules in a constantly changing Britain. Otherwise, we will find ourselves floundering in dangerous waters with some very serious challenges arising from the strains caused by globalisation.

I am not going to pretend that we have all the answers. But we do know that the more we allow groups of people who live and work here to feel that they do not belong to this society the higher the risk of alienation and polarisation in our communities.

When your people come down to Jamaica

We treat them like royalty

So when I come up to England

I’m expecting the same hospitality

I don’t have anywhere to stay

Because I’m coming up on short notice

So please, I’m asking you to fix me up a place inna Buckingham Palace

As we look to the future, it is clear that London’s role as a global hub for talent, innovation, and creativity is only going to grow. With its world-leading academic institutions, thriving tech and arts scenes, and open, inclusive culture, London is not just living up to its legacy, it is building a bright future where the next generation of innovators, scientists, and artists can thrive.

But London’s allure for the brightest and most talented individuals from across the globe is no accident. It is the result of centuries of history, a commitment to innovation and excellence, and most importantly a spirit of openness and diversity. There is still much that needs to change – but it is precisely because of London’s willingness to evolve that makes it such a unique place.

The majority of us, regardless of our diversity and educational achievement know the freedoms, the lifestyle, and the mutual tolerance we enjoy here in London cannot be matched in toto anywhere else in the world.

Maybe that is what London can teach the world.

I would just like to end with mention of another poem by a Caribbean poet – David Neita. David is a lawyer and a poet. He lives in the UK but is currently working overseas otherwise he would have joined us this evening.

It’s a fun poem that treats us to an equal measure of innocence and audacity. A cat may look at a king is an English proverb that means even someone of low status has rights.

Poetry is loved in the Caribbean and despite being British born and bred I also have the passion.

Thank you.

Colleen Harris MVO DL

Communications and diversity professional with more than 30 years’ experience

Colleen Harris MVO DL is Deputy Lieutenant of Greater London and represents Wandsworth. She is a regular speaker and contributor on diversity, the Royal Family and communications. Colleen has spent over 30 years developing and managing strategies for Government Ministers, the UK Royal Family and multilateral organisations including as the Press Secretary to HRH The Prince of Wales, PRO to the former PM, Baroness Thatcher and as Communications Consultant at the WHO and the UN. Wishing to spend more time with her family, Colleen built her own PR and coaching consultancy. She sits on the board of the King Charles III Charitable Fund, St George’s House and Omnibus Theatre.

Published research: Muslims in the European ‘Mediascape’: Integration and Social Cohesion Dynamics – September 2009